CHAPTER IV

Australia and New Zealand

Long before President Johnson's "more flags" appeal, Australia had been providing assistance to South Vietnam. In 1962 Australia sent a thirty man group of jungle warfare specialists as training advisers to the beleaguered nation. Located primarily in the northern provinces, they augmented U.S. advisory teams engaged in a similar mission. Two years later this first group was followed by an aviation detachment consisting of six Caribou aircraft with seventy-four men for maintenance and operations. Integrated into the Southeast Asia airlift, they provided valuable logistic support to dispersed Vietnamese military units. Over the years the Australian cargo aircraft unit was to maintain consistently higher averages in operational readiness and tons per sortie than did equivalent US units.

Australia's support was not confined solely to military assistance. Beginning in July of 1964, a twelve man engineer civic action team arrived to assist in rural development projects. Late in the same year Australia dispatched the first of several surgical teams, which was stationed in Long Xuyen Province. The second team arrived in January 1965 and was assigned to Bien Hoa.

From this rather modest beginning, Australia went on to provide an increasingly wide range of aid to South Vietnam under the Columbo Plan and by bilateral negotiations.1 Unfortunately, not all of South Vietnam's ills could be cured by civic action, and as the situation became more desperate the Australian government planned to increase the size of its military contingent.

In 1965 the Australian Minister stated, in response to American overtures, that if the U.S. and South Vietnamese governments would request it, the Australian government would commit an infantry battalion to South Vietnam. Washington suggest-

[88]

ed that Australia also take on the training mission for Vietnamese Regional Forces. On this proposition the minister expressed some doubt, but speculated that if an infantry battalion were sent to South Vietnam, some trainers -perhaps 100- might be attached to it. The American Ambassador in Saigon, General Taylor, then broached the subject with the South Vietnamese Prime Minister, Dr. Phan Huy Quat.

Talks continued at various levels and on 29 April 1965 Admiral Sharp conferred with the Australian Ambassador at the request of Ambassador Taylor. In the course of the discussions it was learned that the Australian government planned to dispatch to Saigon within fourteen days a small military planning staff to work out the logistic and administrative arrangements with U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, prior to the arrival of the Australian battalion. The battalion force would consist of 900 men, of which 100 were to be logistic and administrative troops; no integral support elements were planned for it. Moving both by sea and air, the unit was to reach South Vietnam by the first week of June. The Australian government agreed that the battalion should be under the operational control of General Westmoreland and that it should be used for the defense of base areas, for patrolling in the vicinity of base areas, and as a mobile reserve. However, the battalion was not to accept territorial responsibility for populated areas or to be involved in pacification operations.

By May when the plans were finalized they differed little from the earlier proposals. The Australian government was to send a task force composed of a headquarters element of the Australian Army, Far East, the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, reinforced, the 79th Signal Troop, and a logistical support company. Also included in this total of approximately 1,400 troops were 100 additional jungle warfare advisers to be used in support of the original training detachments. The task force arrived in Vietnam during the early part of June 1965 and was attached to the US 173d Airborne Brigade.

Operating from Bien Hoa, the 1st Battalion was limited to local security operations during the remainder of the year. This restriction was a result of the Australian government's insistence that Australian forces not be used in offensive or reaction operations except in conjunction with the defense of Bien Hoa air base. Although the interpretation of the restriction was fairly broad in that the battalion could participate in operations within approximately 30 to 35 kilometers of the base, General Westmoreland was not able to plan for its wider, use. For example, on

[89]

30 July, just shortly after their arrival, the troops of the Australian battalion were not permitted by the Australian chief of staff to participate in an operation with the 173d Airborne Brigade. Instead, in order to provide the airborne brigade with a third battalion to secure its artillery and fulfill the reserve role, a battalion from the US 2d Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, was used. For all practical purposes this restriction was removed on 11 August 1965 when Brigadier O. D. Jackson, commander of the Australian Army Force, Vietnam, notified General Westmoreland that his superiors had expanded the Australian contingent's area of operations to encompass those provinces contiguous to Bien Hoa Province. A military working agreement had already been signed between Brigadier Jackson and General Westmoreland on 5 May that gave operational control of the Australian troops to the US commander. The United States also agreed to provide complete administrative and logistical support. In a financial agreement concluded on 7 September, the Australian government agreed to repay the United States for this support. Additional combat and support troops became available on 30 September when a 105mm. howitzer battery, a field engineer troop, an armored personnel carrier troop, a signal troop, and an air reconnaissance flight arrived to augment ~ battalion. At the end of 1965 the Australian strength in South Vietnam was 1,557.

The first contingent had hardly settled down before the Australian government began to consider increasing, the size of its task force. Through their respective embassies m Saigon, the US and Australian ambassadors held low key talks in December 1965 and again in January 1966, but the fear of public criticism initially kept the government of Australia from openly discussing plans to increase its military commitment to South Vietnam. On 8 March, however, the Australian government publicly announced that it would increase the one battalion force to a two battalion force with a headquarters, a special air service squadron, and armor, artillery, engineer, signal, supply and transport, field ambulance, and ordnance and shop units. At the same time the government suggested that the Australian Caribou flight, along with eight UH1B helicopters, be given the primary mission of supporting the Australian task force. This commitment raised the Australian troop strength to slightly over 4,500.

General Westmoreland tentatively decided that the Australian task force would be based at Ba Ria, the capital of Phuoc Tuy Province, and placed under the control of the II Field Force

[90]

TROOPS OF THE ROYAL REGIMENT after arrival at Tan Son Nhut Airport.

commander. He felt that this arrangement would place a large force in the area of Highway 15, a priority line of communication, and at the same time keep the Australian task force well away from the Cambodian border. Australia maintained diplomatic relations with Cambodia and for that reason had requested US assurance that Australian units would not be used in operations along the Cambodian border. Additional artillery support, as needed, would be provided by the II Field Force. It was also decided that the eight UH1B helicopters would come under the command of the task force; however, the request for task force control of the Australian Caribou units was denied because the Caribou units had a lift capacity in excess of the task force needs. It was agreed that reinforcing aircraft would be provided as needed.

During the first half of March 1966 the MACV staff and an Australian joint service planning team developed new military working arrangements and planned for the deployment of the task force. The agreement signed by both parties on 17 March superseded the previous agreement of 5 May 1965. The new agreement confirmed the mission of the Australian task force in

[91]

LIVING QUARTERS AT AN AUSTRALIAN FIRE SUPPORT BASE

Phuoc Tuy Province; the area of operations in the province was along Highway 15 and in the eastern portion of the Rung Sat Special Zone. Days later a financial arrangement was made by which Australia agreed to reimburse the US government for support provided to Australian troops in South Vietnam.

The advance party for the 1st Australian Task Force left for South Vietnam on 12 April and the main body followed in several increments. After a brief training period, operational control of the task force passed from the Commander, Australian Force, Vietnam, to the Commanding General, II Field Force, Vietnam.

Discussions were meanwhile under way concerning a U.S. proposal that would bring an Australian squadron of twelve Caribou aircraft to South Vietnam to make up shortages in air sorties expected to result from US deployment plans. General Westmoreland planned to employ the unit in support of South Vietnamese, South Korean, and US ground operations as well as those conducted by the Australians. Operational control of the squadron would be given to the Seventh Air Force and, if politically acceptable to the Australian government, General Westmoreland planned to use the squadron against targets in Laos. On the sixth of May Admiral Sharp took the proposal to the US Joint Chiefs of Staff. The State Department concurred in the request and contacted the Australian Embassy in Wash

[92]

ington to confirm that the squadron was available for deployment. The plan was never carried through.

With the arrival of reinforcements, the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, left South Vietnam, having completed almost a full year of combat duty. In leaving, the "diggers" could point with pride to a creditable performance during their stay, highlighted by participation in no fewer than nineteen major operations. Of particular note was an operation conducted in January 1966 which resulted in one of the biggest intelligence coups of the war up to that time. During a sweep of the so-called Iron Triangle, an area near Saigon heavily fortified and controlled by the Viet Cong, the Australian unit discovered a vast complex of tunnels, dug 60 feet deep in some places, which turned out to be a Viet Cong headquarters. In addition to capturing five new Chinese Communist antiaircraft duns, the Australians discovered 6,000 documents, many revealing names and locations of Viet Cong agents.

The effectiveness of the new Australian contingent was clearly demonstrated during the remainder of the year during which Australian troops killed more than 300 of the enemy, captured large stores of material, and helped secure Highway 15. Particularly successful was a battle conducted on 18 August 1966. Sweeping through a French rubber plantation called Binh Ba, 42 miles southeast of Saigon, Delta Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, ran head on into a force estimated as 1,500 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. In the initial exchange and at pointblank range the Aussies suffered most of their casualties. For three hours and in a blinding monsoon rain this company of approximately 108 men fought the enemy to a standstill. Taking advantage of their numbers, the enemy troops tightened the noose around the company, charged in human wave attacks, but were beaten back continually. The fighting became so intense that the Australians ran low on ammunition and their helicopter pilots braved both the rain and heavy enemy fire to effect resupply. With the noise deadened by the downpour, a company of Australian reinforcements in armored personnel carriers moved unseen through the surrounding terrain and provided supporting fires with .50 caliber machine guns. At the same time Australian and other allied artillery units found the range to the targets. In the end, Delta Company routed the enemy troops from the battlefield, forcing them to leave behind 245 of their dead. During roughly four hours the Hussies killed

2 A sobriquet variously ascribed to the prevalence of gold diggers in early Australian Army units and to the Australians' trench digging activities in World War I.

[93]

AUSTRALIAN SOLDIER MANS MACHINE GUN POSITION

more of the enemy than they had in the entire preceding fourteen months.

Because of the forthcoming Australian elections, the Commander, Australian Force, Vietnam, did not expect to see any additional troops until after November. While Australian officials, both military and civilian, were aware of the task force's need for a third battalion, they did not wish at that time to add fuel to the fires of the critics of Australia's Vietnam policy. This course proved to be wise. Throughout the fall heated exchanges took place in the Australian House of Representatives over the troop question. Government officials continuously stated that no decision to increase Australian forces in South Vietnam had been taken, but at the same time they would not exclude the possibility of such a decision in the future. The Australian government gained additional maneuvering room when on 20 November 1966 the voters increased the ruling coalition's voting margin in the House of Representatives from nineteen to forty-one seats.

These events and the continuing controversy failed to interfere with other aid programs to South Vietnam and on 29 Nov

[94]

MEMBERS OF AUSTRALIAN CIVIC ACTION TRAM confer with village officials on plans for local improvements.

[95]

ember a third Australian surgical team arrived in Saigon. This new group was assigned to the city of Vung Tau, and its thirteen members brought to thirty-seven the number of Australian medical personnel in South Vietnam.

From 1966 through 1968 Australian economic and technical assistance totaled more than $10.5 million and included the provision of technicians in the fields of water supply and road construction, experts in dairy and crop practices, and the training of 130 Vietnamese in Australian vocational and technical schools. In the area of refugee resettlement, Australia had provided over one and a fourth million textbooks, thousands of sets of hand tools, and over 3,000 tons of construction materials. Well recognizing the need and importance of an adequate communications system to allow the government to speak to the people, Australian technicians constructed a 50-kilowatt broadcasting station at Ban Me Thuot and distributed more than 400 radio receivers to civilian communities within range of the transmitter.

With a strong endorsement from the voters, the Australian government acted quickly to increase the size of the military contribution. The first step was to seek from the chairman of the Chief of Staff Committee, Australian Force, Vietnam, recommendation for the composition of additional forces which could be provided to South Vietnam on short notice. With little guidance and no knowledge of the ability of the US and Vietnam governments to accommodate additional units, the chairman nonetheless made a recommendation. Cognizant of the desire of the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal Australian Navy for action in South Vietnam and aware of the strong support given to a tri-service contingent by the Australian Minister of Defense, he proposed an augmentation consisting of elements from all three services. Included in the offer was the H.M.A.S. Hobart, a guided missile destroyer; a Royal Navy diving team; a squadron of eight B57 Canberra bombers, an 80-man civil affairs unit, and a 916-man increase to the existing Australian Army units in South Vietnam. Australia's three services and defense department supported the concept and were in accord with the idea that Australia should be the first nation, other than the United States, to support South Vietnam with a tri-service contingent.

With regard to the ground forces, the 916 Australian Army reinforcements were provided for integration into units already in South Vietnam. Of that number, 466 were requested additions to the tables of organization and equipment of established

[96]

units, and the remaining 450 constituted combat reinforcements to the 1st Australian Task Force.

The United States welcomed the idea of an increased Australian contingent and concurred with the request of the Australian government that H.M.A.S. Hobart and the Canberra squadron be deployed in conjunction with U.S. forces. It was expected that the Hobart would remain under Australian command but under operational control of the US Navy. Until relieved by a like vessel, the ship would be available in all respects as an additional ship of the US Navy force and without operational restrictions. Anticipated missions included shore bombardment of both North and South Vietnam, interdiction of coastal traffic, picket duties for carrier operations, and general operations in support of naval forces at sea. The command and control arrangements for the Canberra squadron would be similar to those for the Hobart, with the aircraft located where they could support Australian forces as part of their mission. The squadron would perform routine maintenance in Vietnam while relying on major maintenance from Butterworth, Malaysia, where two float aircraft would be retained. (While they were agreeable to the maintenance arrangements, the Malaysians stressed the fact that they did not care to publicize the matter.) The squadron was also to deploy with a 45-day stockage of 500-pound bombs. Other logistical support in the form of petroleum products, rations, accommodations, engineer stores, and common usage items would be provided by the United States on a reimbursable basis.

The initial conference between the Australian planning group, headed by Air Vice Marshal Brian A. Eaton, and the staff of US ?Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, took place in Saigon during 37 January 1967. At this time logistical matters and command and control arrangements were firmed up as previously discussed. The Canberras would be based at Phan Rang and employed in the same manner as all other Seventh Air Force strike aircraft. Operational control was given to the Commander, Seventh Air Force, while the Commander, Australian Force, Vietnam, retained command and administrative control. Deployment of the Canberra squadron was thought ideal in view of the fact that the aircraft were considered obsolete and were due to be replaced in Australia by F111 aircraft.

When the conference turned to naval matter, US representatives asked for more details on the capabilities of the Australian diving team. The general concept of employment envisioned that the team would be integrated into operations of the Commander, US Naval Forces, Vietnam, Rear Admiral Norvell

[97]

G. Ward. Australian and US Navy representatives were meeting meanwhile in the Philippines to develop arrangements for the logistic and administrative support of H.M.A.S. Hobart while it operated with the Seventh Fleet. The Saigon conference agreed that MACV need not be involved in any arrangements pertaining to the Hobart.

The Australians returned home from South Vietnam seemingly pleased with the arrangements made and appreciative of US assistance, especially since the government of Australia had allocated only limited time to get the operation moving. The Canberra squadron had been directed to be operationally ready by 1 April 1967. The Phan Rang facilities were crowded but the Australian squadron was only a small addition and the assurances given the Australians of their need and value made a lasting impression. In January and February the Australian 5th Airfield Construction Squadron left for South Vietnam to build the maintenance hangar and other facilities for the squadron. On 19 April eight of the ten Canberra bombers deployed to South Vietnam from Butterworth the first such aircraft to enter the war. Personnel numbered approximately 40 officers, 90 noncommissioned officers, and 170 other enlisted men.

The H.M.A.S. Hobart was integrated into the war effort when she relieved a US Navy destroyer off Chu Lai on 31 March. Operational employment, logistic support, command relations, and use of clubs, messes, and exchanges were arranged on a navy-to-navy basis.

In January 1967 the Australian government had indicated that ten navy antisubmarine warfare pilots qualified in the H34 helicopter might be deployed to South Vietnam. MACV believed that after ten hours of transitional training in UH1D aircraft the pilots could be integrated directly into US Army aviation units. It was not until April, however, that the offer was formalized: eight pilots and some thirty men for maintenance and support were offered to relieve US troops operating in support of the Australian task force. The pay and allowances of this contingent would be paid by Australia while the United States would provide the aircraft and logistical support. The men would be integrated into US units and would relieve US troops on an individual basis.

To facilitate administration, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff had requested that the Australian pilots be stationed near a Royal Australian Air Force squadron. They further asked that, if practicable, the Australians be assigned to US units that normally supported the Australian task force. General Westmoreland

[98]

pointed out that US Army helicopter units were not assigned to support specific organizations or task forces and that the assignment of the Australians would be dictated by the tactical situation. Later discussions revealed that while the Australian government wished to attach its troops to the Australian unit at Vung Tau for administrative support, there was no official requirement for Australian pilots to be assigned to US units supporting the Australian task force. General Westmoreland replied that if the proposed Australian offer materialized, the Australians would be assigned to a helicopter company of the 12th Combat Aviation Group in the Bien Hoa-Bearcat area. From this location they would support units in the III Corps Tactical Zone where the Australian ground troops were stationed. Upon the arrival of the 135th Aviation Company in Vietnam, they would be reassigned to that unit. The 135th Aviation Company was to be stationed at Nui Dat, the location of an Australian Air Force helicopter squadron, only 35 kilometers northeast of Vung Tau. From Nui Dat the 135th Aviation Company would support the 1st Australian Task Force and others. Should the 135th arrive in Vietnam before the Australian helicopter contingent it would be assigned directly to that contingent. An Australian government request that the pilots be permitted to operate helicopter gunships was also honored.

In October 1967 the Prime Minister of Australia announced new plans to increase the Australian forces in South Vietnam by another 1,700 troops, thus raising the Australian contingent from about 6,300 to over 8,000 men. Increases in the ground forces were to consist of one infantry battalion, one medium-tank squadron with Centurian tanks (250 men), an engineer construction troop of 45 men, and an additional 125 men to augment the headquarters group. The infantry battalion, the 3d Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, was to be deployed during November and December with the other units following as transportation became available. The additional air force contingent was to consist of eight Iroquois helicopters, ten helicopter pilots, twenty enlisted crew members, and 100 maintenance men. The helicopters and personnel were to be assigned to the Royal Australian Air Force No. 9 Helicopter (Utility) Squadron which had deployed the previous June. The Navy was to provide the small number of antisubmarine warfare helicopter pilots and maintenance personnel discussed earlier in the year.

The added force, deployed over an eight month period beginning in November 1967, totaled 1,978, slightly over the proposed figure. The 3d Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, with

[99]

SOLDIER OF ROYAL AUSTRALIAN REGIMENT pauses sweep of cultivated area around a village.

combat support and logistic elements closed in Vietnam in December 1967 and was attached to the 1st Australian Task Force in the III Corps Tactical Zone. The tank squadron with its logistical support elements arrived in late February and early March of 1968 with fifteen operational Centurian tanks. Eleven more tanks were added in September. The No. 9 Helicopter Squadron received its eight additional helicopters in July, giving that unit sixteen helicopters. A cavalry troop of thirty men was added in October 1968.

The type and degree of support provided the additional Australian forces was in accordance with a new military working arrangement signed on 30 November 1967. Under its terms the Australian government was to reimburse the US government at a capitation rate for the support provided. US support included base camp construction and cost of transportation within Vietnam for supplies of Australian Force, Vietnam, arriving by commercial means; billeting and messing facilities, but not family quarters for dependents (payment of meals and billeting service charges were paid for by the individual in the Saigon area);

[100]

some medical and dental care in Vietnam but not evacuation outside Vietnam except for emergency medical evacuation, which was provided on the same basis as that for US troops; mortuary service, including preparation of the bodies for shipment, but not transportation outside Vietnam; transportation, including use of existing bus, sedan, taxi, and air service operated by the United States in Vietnam; delivery of official messages transmitted by radio or other electrical means through established channels; use of US military postal facilities, including a closed pouch system for all personal and official mail (1st through 4th class); exchange and commissary service in Vietnam; special services, including established rest and recreation tours; necessary office space, equipment, and supplies; and spare parts, petroleum products, and maintenance facilities for vehicles and aircraft within the capabilities of US facilities and units in Vietnam.

Agitation in Australia for troop withdrawals, noticeable in 1968, increased as the year 1969 came to a close, especially in view of US redeployment plans. On 15 December 200 shop stewards and 32 labor union leaders representing over 1.5 million Australian voters passed a resolution protesting Australian participation in the war. Coupled with this was a second resolution calling upon Australian troops in South Vietnam to lay down their arms and refuse to fight. The next day the Secretary of the Trades Council criticized the resolution as being, " . . . a call for mutiny." On 16 December the Australian Prime Minister felt it necessary to outline the government position on South Vietnam. In a television address he stated:

In my policy speech before the last election, I had this to say to the Australian people: "Should there be developments (in Vietnam) which result in plans for continuing reduction of United States Forces over a period, we would expect to be phased into that program." Since I spoke, developments have taken place, and you have today heard the announcement by the President of the United States that a further 50,000 troops are to be withdrawn over the next few months . . . . I have spoken directly with the President of the United States, in accordance with arrangements made on my last visit, and we were in complete accord in agreeing, in principle, that should the future situation permit a further substantial withdrawal of troops, then some Australian troops should be included in the numbers scheduled for such reduction. Such agreement in principle is all that has been reached, or all that can at present be reached . . . . So I wish to make it dear: That there is no firm timetable for further withdrawal of United States troops of which I know . . . . That there is no arrangement made as to how great any Australian reduction, which may take place in the future, will

[101]

be . . . . But these things are clear: We will not abandon the objects for which we entered the Vietnam War. We will participate in the next reduction of forces at some stage, when it comes . . . . We will remain to attain the objectives which we started to reach, but we are glad we are able to make reductions without endangering those objectives.

The first open talks with the Australians concerning troop redeployment were held on 28 January 1970 when the chief of staff of the Australian Force, Vietnam, met with the assistant chief of staff, J3, of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, to discuss Australia's intentions on troop withdrawal. The Australian chief of staff could not confirm the existing rumors that Australian troops would be pulled out in April or May; he indicated that he had no knowledge of the subject other than the Prime Minister's announcement of 16 December. He went on to add that he believed only one battalion would be withdrawn initially and the pace of future moves would be keyed to moves by the United States.

On the second day of April the Military Assistance Command Training Directorate and the Central Training Command convened a conference to discuss an Australian proposal for in

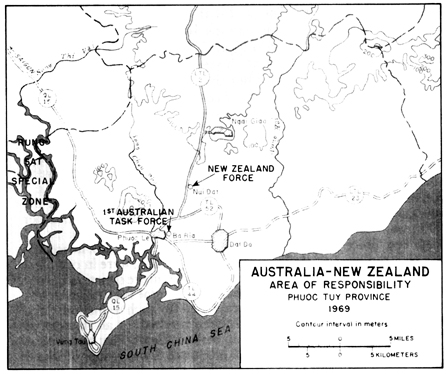

MAP 6 AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Area of responsibility Phouc Tuy Province 1969

[102]

creased Australian support of Vietnamese training. The exact terms of this proposal had not yet been determined but the training would be supplied for the Regional and Popular Forces in Phuoc Tuy Province. (Map 6) Any increased training effort on the part of the Australians was to be linked to future withdrawals of Australian troops. No definite dates for withdrawals or specific numbers of men to be withdrawn had been decided upon.

The situation became clearer when the Australian government announced on 20 August the pending redeployment of the 8th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment. This unit of approximately 900 men returned home about 12 November, leaving behind a force level of 6,062. The move was accompanied by an offer of approximately $3.6 million (US) to South Vietnam as a direct grant for defense aid. This was the first phase of the Australian withdrawal; future reductions in troops were to be handled in much the same manner.

Almost one year later, 18 August 1971, the Australian government announced that it would withdraw its combat forces from South Vietnam in the next few months. Prime Minister William McMahon stated that the bulk of the force would be home by Christmas. To help offset the troop reduction the Australian government pledged $28 million in economic aid for civil projects in South Vietnam during the next three years. This placed the total monetary cost to Australia for active participation in the war in the neighborhood of $240 million.

The forces of discontent plaguing the Australian government's Vietnam policy were at work in New Zealand as well, but on a smaller scale. Just as New Zealand was prompted by the same rationale as Australia to enter the conflict in South Vietnam, it was prompted to leave for similar reasons. The Australian announcement of a troop reduction on 20 August 1970 was accompanied by a like announcement from New Zealand. On that date the Prime Minister stated his intention of reducing the New Zealand contingent by one rifle company of 144 men. Then in November 19'70 New Zealand made plans to send a 25-man army training team to South Vietnam in early 1971. This announcement followed closely and was intended to offset the 12 November departure of the New Zealand rifle company. It was proposed that the training team serve as a contribution to a joint Vietnam-New Zealand training facility at the Chi Lang National Training Center in Chau Doc Province.

New Zealand again followed suit when on 18 August 1971 its government announced with Australia that New Zealand too would withdraw its combat forces from South Vietnam. In Wel-

[103]

MEMBERS OF ROYAL NEW ZEALAND ARTILLERY carry out a fire mission.

lington, New Zealand's Prime Minister, Sir Keith J. Holyoake, said that his country's combat forces would be withdrawn by "about the end of this year [1971]."

The New Zealand contingent in Vietnam served with the Australians. Both nations realized that their own vital interests were at stake. The decline of British power had made the security of New Zealand more dependent upon the United States and upon damming the flood of what Prime Minister Holyoake called in 1968 "terror and aggression." The fundamental issues, Holyoake said, were simple: "Whose will is to prevail in South Vietnam the imposed will of the North Vietnamese communists and their agents, or the freely expressed will of the people of South Vietnam?"

Discussion surrounding the nature of New Zealand's aid to South Vietnam was conducted at various levels. The U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, became involved when Lieutenant Colonel Robert M. Gurr, a representative of New Zealand's Joint Chiefs of Staff, met with MACV representatives during the period 510 June 1963. The New Zealand government was interested in such categories of assistance as workshop

[104]

teams, engineers, field medical elements, naval elements, and army combat elements. Information on the possible use of New Zealanders in each of these categories as well as other recommendations was provided. Colonel Gurr pointed out that while his government was reluctant to become deeply involved in combat operations for political reasons, the New Zealand military was interested in gaining knowledge of Vietnam and experience in combat operations.

New Zealand first contributed to the defense of South Vietnam on 20 July 1964 when an engineer platoon and surgical team arrived in Vietnam for use in local civic action projects. Then in May 1965 the government decided to replace the detachment with a combat force consisting of a 105-mm. howitzer battery. This unit, the 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery, arrived on 21 July, was put under the operational control of MACV, and was attached to the 173d Airborne Brigade with the primary mission of supporting the Australian task force in Phuoc Tuy Province. The following month a military working agreement was signed under which the United States agreed to furnish field administrative support. Although no financial working agreement had been signed by the end of the year, New Zealand was reimbursing the United States for the cost of support given. The contingent from New Zealand at this time numbered 119.

The year 1966 opened with discussions between General Westmoreland and the Ambassador of New Zealand over the possibility of increased military aid to South Vietnam. Specifically, General Westmoreland hoped that New Zealand could provide a battalion of infantry for a three battalion Australian-New Zealand (ANZAC) brigade. While sympathetic to the proposal, the ambassador said there were political considerations governing the increase that were beyond his authority. In late February, a representative from the New Zealand Ministry of External Affairs met with General Westmoreland and indicated an interest in rounding out the 105-mm. Howitzer battery from four to six guns. Despite election year pressure and subsequent political considerations tending to limit aid to nonmilitary areas, New Zealand announced on 26 March 1966 its decision to add two howitzers and twenty-seven men to its force in South Vietnam. In addition the surgical team in Qui Nhon was to be increased from seven to thirteen men.

During a visit to South Vietnam the Chief of the General Staff, New Zealand Army, told General Westmoreland that he believed New Zealand might respond to requests for additional

[105]

military assistance, but not until after the November elections. Several possibilities were mentioned, including an infantry battalion of four companies and a Special Air Services company. Both units were in Malaysia, but could be redeployed to South Vietnam. Also under consideration was the use of an APC platoon and a truck company. The Army chief admitted that civilians and some military men in the New Zealand Defense Ministry did not share his views, hence there was little chance for the immediate implementation of the proposals.

The elections in the fall of 1966 seemed to define New Zealand's policy in regard to South Vietnam. With a solid voter mandate the New Zealand Prime Minister instructed his Defense Minister to review the entire situation and in doing so to consider the use of all or part of the New Zealand battalion of the 28th Commonwealth Brigade (Malaysia) for service in South Vietnam.

The New Zealand government then summarized the possibilities for military aid to Vietnam. The army possibilities for deployment were a 40-man Special Air Services company (squadron), or five 20-man troops to alternate 6-month periods of duty with an Australian counterpart organization. An armored personnel carrier troop of 30 men and 12 carriers was another possibility, but not for the immediate future. Also considered was an infantry rifle company from the battalion in Malaysia or the entire battalion. Last, small additional administrative and logistical support units were suggested by the Australians. Likely Air Force increases were from four to six Canberra (B-57) flight crews supported by forty to fifty ground personnel to be integrated into either US or Australian Canberra squadrons. Because it was not practical to use the B-57's of the New Zealand Air Force with U.S. bombers, it was decided to leave them in New Zealand with a training mission. Other Air Force possibilities were a few fully qualified Canberra or Vampire pilots for a US sponsored training program for F4 aircraft and subsequent combat operations; the addition of a few operations, intelligence, and forward air controller personnel; several Bristol freighter transports with crews and necessary ground support personnel; and finally, air crews and ground support personnel for Iroquois helicopters. Possible naval contributions ranged from the deployment of the frigate Black-pool from Singapore to a station with the Seventh Fleet off the coast of Vietnam to the man for man integration of from 20 to 40 men on US patrol craft. Besides all this, the government of New Zealand had been considering the likelihood of substituting a medical team drawn

[106]

AUSTRALIAN CIVIL AFFAIRS TEAM MEMBER TREATS VILLAGE BOY

from the armed forces for the three civilian medical teams previously programmed for Binh Dinh Province.

The views of officials of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the office of the Commander in Chief, Pacific, on these proposals were passed to New Zealand in order of their preference. The United States preferred a full infantry battalion, an infantry rifle company, a Special Air Services company (special forces), and an armored personnel carrier troop, in that order. The infantry battalion from Malaysia could be used effectively in any corps tactical zone, but it would probably be most effective if attached to the Australian task force, thereby doubling the force's capacity to conduct search and clear operations. Moreover the move would enhance security in the Vung Tau area and aid the revolutionary development program. The existing two battalion force had limited the size of the task force operations to one reinforced battalion, the other battalion being required for base camp security. If only an infantry rifle company were available, it would be employed as part of the Australian task force. The Special Air Services company (squadron) would help fill the need for long-range patrols and reconnaissance as

[107]

the allied offensive gained momentum. The company could be used effectively in any corps area, but its use was preferred in the III Corps Tactical Zone under the operational control of II Field Force headquarters. The unit was to be employed alone, in a specified remote area, to observe and report on enemy dispositions, installations, and activities. The armored personnel carrier troop would be employed with the Australian task force, where its presence would increase the force's ability to safeguard roads as well as to conduct operations to open lines of communication.

With regard to New Zealand Air Force contributions, a Canberra squadron was believed to be the most desirable, followed by the Bristol freighter transports, support for Iroquois helicopters, F4 pilots, intelligence specialists, and forward air controllers. The bombers would operate with the Australian squadron while the Bristol freighters would provide logistic support in Vietnam as well as lift for the Australian task force. Up to 25 officers and 25 enlisted men could be used in conjunction with the Iroquois helicopter company and it was hoped that the men would be available for a minimum of six months. Intelligence specialists and forward air controllers would be used to coordinate and direct tactical air and artillery support for ground forces. Augmenting the Seventh Fleet with a Black-pool type of destroyer would be especially desirable, as would the integration of a New Zealand contingent with US crews on either MARKET TIME Or GAME WARDEN patrol craft. No command and control problems were anticipated in any of these proposals.

The reviews and discussions surrounding increased New Zealand Air Force contributions finally resulted in some action. On 8 March 1967 the Australian government announced that it intended to send a sixteen man tri-service medical team to Binh Dinh Province in late May or early June to replace the US team at Bong Son. At the same time a decision was made to double New Zealand military forces in South Vietnam through the deployment of a rifle company. Accompanied by support troops, this unit would be drawn from its parent battalion in Malaysia and rotated after each six-month tour of duty. The first element of V Company, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, arrived in South Vietnam on 11 May 1967. In October General Westmoreland learned that the New Zealand government would add still another rifle company to its contingent some time before Christmas. This unit, W Company, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, plus engineer and support troops arrived during the period 1617 December 1967. Both rifle companies were integrated with an Australian unit to form an ANZAC battalion. A

[108]

SOLDIER OF ROYAL NEW ZEALAND ARMY COOKS HIS LUNCH

platoon of New Zealand Special Air Services also arrived in December and was integrated into a similar Australian unit. These deployments brought the New Zealand troop strength up to its authorized level for a total commitment of approximately 517 men.

Logistical support accorded the New Zealand forces was provided in a military working arrangement signed 10 May 1968. Under the terms of this arrangement, the New Zealand government was to reimburse the US government at a capitation rate for the support provided. US support included base camp construction and transportation costs within Vietnam for New Zealand force supplies arriving by commercial means; billeting and messing facilities (but not family quarters for dependents); some medical and dental care in Vietnam but not evacuation outside Vietnam except emergency medical evacuation, such as that provided for US troops; use of US operated bus, sedan, taxi, and air service; delivery of official messages transmitted by radio or other electrical means through established channels; use of US military postal facilities, including a closed pouch system for all personal and official mail; exchange

[109]

and commissary service in Vietnam; special services, including established rest and recreation tours; necessary office space, equipment, and supplies; spare parts, petroleum products, and maintenance facilities for vehicles and aircraft within the capabilities of US facilities and units in Vietnam.

There was no significant change in strength or mission for the New Zealand forces in South Vietnam during the remainder of 1969. (Table 2)

TABLE 2 - LOCATION, STRENGTH, AND MISSION OF NEW ZEALAND FORCES JUNE 1969

| Unit | Location | Authorized Strength | Mission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headquarters, New Zealand Force, Vietnam | Saigon, Gia Dinh | 18 | Comd and admin support |

| 161st Battery, RNZIR | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 131 | Combat |

| RNZIR component; various appointments with 1st Australian Task Force | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 18 | Combat |

| V Company, RNZIR | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 150 | Combat |

| W Company, RNZIR | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 150 | Combat |

| Administrative Cell | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 9 | Admin support |

| No. 4 Troop, NZ SAS | Nui Dat, Phuoc Tuy | 26 | Combat |

| Logistical support element | Nui Dat, Vung Tau, Phuoc Tuy | 27 | Logistical support |

| 1 NZ Svcs Med Team | Dong Son, Binh Dinh | 16 | Asst to GVN |

While there appeared to be some hesitancy over the type and amount of New Zealand's military aid, the country's financial assistance to South Vietnam continued unabated. Commencing in 1966, financial aid averaged approximately $350,000 (US) annually. This sum financed several mobile health teams to support refugee camps, the training of village vocational experts, and the establishment of the fifteen man surgical team deployed to the Qui Nhon-Bong Son area. Other appropriated support funded the cost of medical and instructional material for Hue University and the expansion of Saigon University. During the 196768 period nearly $500,000 (US) of private civilian funds were donated for Vietnamese student scholarships in New Zealand and increased medical and refugee aid.

For a number of years the Australian and New Zealand troops, distinctive in their bush hats, operated in their own area of responsibility in Phuoc Tuy Province. Their job was essentially to conduct offensive operations against the enemy through

[110]

AUSTRALIAN SOLDIER SEARCHES FOR ENEMY IN HOA LONG VILLAGE

"clear and hold" actions. Related and equally important tasks included the protection of the rice harvest and a civic action program. When the Australian task force was introduced into Phuoc Tuy Province in 1965, its commanding general, recognizing the need to develop rapport with civilians, directed the task force to develop an effective modus operandi for civic action operations. After several months and considerable coordination with other agencies a concept of operations was developed. In July 1966 the program went into effect.

In the first stage, civic action teams composed of four men each were sent to hamlets in the area surrounding the task force command post in Long Le District. At this time the objective was simply to develop rapport with the local population; the teams made no promises and distributed no gifts. The Long Le area had been largely under Viet Cong domination since the early fifties and the people therefore were at first somewhat reluctant to accept the Australians, who looked and spoke like Americans, but yet were different. This reluctance was gradually overcome.

The first stage lasted for approximately two weeks and was followed by the preparation of a hamlet study that outlined the

[111]

SOLDIER OF ROYAL, AUSTRALIAN REGIMENT WITH M60

[112]

type of projects to be undertaken. Some material support was solicited from US Agency for International Development, Joint US Public Affairs Office, and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. In addition, the Australians had a sizable fund at their disposal for the purchase of materials and payment of labor. In executing the plan, priorities for project construction were set and forwarded to the province chief for his approval. After approval, construction commenced. The results were impressive. In a one year period in the district town alone, eight classrooms, a Vietnamese information service headquarters, a district market, a maternity ward, a three-room dispensary, a town meeting hall, large warehouses, a dozen capped wells, a district headquarters building, a police checkpoint, and several other hard structure projects were completed.

In the execution of this program the Australians initially committed one basic error which is worth noting. They did not recognize sufficiently the critical importance of the hamlet, village, and district governments and the imperative need to consult, work with, and coordinate all projects with local Vietnamese officials. This lack of coordination resulted in some problems. For example, maintenance on projects was not performed because no one felt responsible and no prior commitment had been made. And while the projects were thought to be in the best interests of the local population by Vietnamese officials, their precise location and design did not necessarily match the people's desires.

The people respected the Australians for their fine soldiering and discipline. In a study of Phuoc Tuy Province the respondents remarked that Australians never went over the 10 miles per hour limit in populated areas, individually helped the Vietnamese, and paid fair wages for skilled and unskilled labor.

One reason for the success of the Australians in Vietnam was their experience of over a generation in fighting guerrilla wars. The Australian Army, before going to Vietnam, saw action in the jungles of Borneo against the Japanese and then spent twelve years helping the British put down a Communist insurgency in Malaya. Another reason for the effectiveness of the Australian soldiers could be attributed to their training. Because of its small size the Australian Army trained exclusively for the one kind of war it was most likely to face guerrilla war in the jungles and swamps of Asia. Furthermore the army, composed largely of volunteers, is a highly specialized organization. One ranking Australian officer who advised the South Vietnamese security forces compared his country's army to the Versailles

[113]

ROYAL AUSTRALIAN AIR FORCE CIVIC TEAM moves out past Vietnamese temples to Mung Duc

restricted German Army after World War I which became so "cadreized" that even the lowest ranking private could perform the duties of a captain.

[114]

Notes for Chapter IV

1. The Columbo Plan for Cooperative Development in South and Southeast Asia was drafted in 1951; with headquarters in Columbo on Ceylon, the cooperative had a membership of six donor countries Australia, Canada, Great Britain, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States and eighteen developing countries. Its purpose was to aid developing countries through bilateral member agreements for the provision of capital, technical experts, training, and equipment. (Return to page)

page created 18 December 2002