CHAPTER V

The Republic of China

Nationalist Chinese contributions to the war in Vietnam were limited by extremely sensitive considerations involving the possible reactions of Peking and Saigon to the presence in South Vietnam of Chinese in military uniform. Offers of combat troops from the Republic of China for Vietnam were made early in the war by President Chiang Kai-shek to President Johnson. Later, on 24 February 1964, Chiang Kai-shek again stressed to Admiral Jerauld Wright, Ambassador to the Republic of China, and Admiral Harry D. Felt, Commander in Chief, Pacific, that the United States should plan with the government of the Republic of China for possible use of the republic's armed forces against North Vietnam. Dr. Yu Ta-Wei, Minister of Defense, also pursued the subject of troop contributions with Admiral Felt, including discussion of a possible Chinese Nationalist attack on the island of Hainan. The United States was wary, however, of military assistance from the Chinese Nationalists and excluded their government when soliciting the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and other countries for contributions of noncombat units in uniform. There was some concern on the one hand that the Republic of China would feel offended if left out, but on the other hand the United States was aware of the Chinese Communist view of Nationalist Chinese intervention and decided not to risk provoking Communist China. The United States decided that the dispatch of Nationalist engineer units would not provoke overt Chinese Communist retaliation, even though the move could provide a pretext for intervention at a later date. To preclude the possibility of Chinese Communist interference in the Formosa Strait, or elsewhere for that matter, the United States tried to play down the role of Republic of China military assistance and direct the aid of the republic primarily to the field of civic action.

Assistance from the Republic of China arrived in South Vietnam in the form of an advisory group on 8 October 1964. The mission of this Republic of China Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, was to furnish political warfare advisers and

[115]

medical men and to help with the problem of refugees. Three LST crews were also to assist in the waterborne logistical effort. The LST's belonged to the U.S. Navy port, Keelung, on Taiwan.

Two political warfare advisers were stationed in each of the four corps tactical zones, three advisers at the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces Political Warfare College in Dalat, and the other three with the Armed Forces General Political Warfare Directorate in Saigon. Sponsored and supported by the US Agency for International Development, the seven-member provincial health assistance team worked in the provincial hospital at Phan Thiet. The Republic of China also provided two C46 aircraft and crews for refugee relief missions in South Vietnam. By the end of 1965 assistance from the Republic of China had been increased to include eighty-six agricultural experts and a nine-man mission to supervise construction and operation of the 33,000-kilowatt power plant located at Thu Duc.

Additional aid was sought from the republic early in 1966 when the United States requested six LST's for service in South Vietnam. Originally given to the Nationalists under the US Military Assistance Program, the ships were to be manned by Chinese crews in civilian clothing and fly US flags. The United States would bear the cost of crew wages and ship maintenance. The mission of the ships was to fill the need for shallow-draft coastal vessels and help ease harbor congestion. The Republic of China was able to provide only two ships; their transfer took place in April in a low key atmosphere without publicity.

In June General Westmoreland was asked to comment on the possibility of having Chinese Nationalist troops in South Vietnam. Since other Free World forces had been introduced, the prospect could possibly now be viewed in a different light. From a purely military point of view, General Westmoreland believed the use of Chinese Nationalist troops would be highly desirable. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, would welcome the addition of a well-trained, motivated, and disciplined marine brigade as early as it could be deployed; but from a political point of view, there were still many reservations concerning the introduction of Chinese Nationalist troops into the Vietnamese War. The US Embassy at Saigon declined to make any specific comments or recommendations without first consulting the government of South Vietnam; however, the classification given to the subject made consultation impossible. It was the US Embassy's belief that while some key figures in the government of South Vietnam would see the advantages of using troops from the Republic of China there was sufficient cause to believe that a

[116]

Chinese Nationalist involvement might be counterproductive. The embassy thought that while the introduction of Chinese Nationalist troops in South Vietnam probably would cause no change in Chinese Communist strategy, the rest of the world might view the act as a prelude to another war. In addition, the traditional anti-Chinese attitude of the Vietnamese had to be taken into account because it could have a strong bearing on the acceptability of Chinese Nationalist troops to the government of South Vietnam. Weighing both the military and political aspects of the question, General Westmoreland recommended that Republic of China troops be deployed only when the political questions had been resolved.

During 1967 the team of Chinese advisers on electric power was increased to thirty-four and a sixteen-man surgical team was introduced into Vietnam to assist in expanding public health programs. In mid-June 1967, having already obtained Vietnam government approval, the Republic of China military attaché in Saigon wrote General Westmoreland for permission to send four groups of officers to South Vietnam for one month's on the-job training. The groups would consist of from eight to ten officers each in the branches of intelligence, artillery, armor, ordnance, and engineering and would be assigned to a compatible US unit. General Westmoreland, with concurrence from the US Embassy, opposed the project for several reasons. First, the military working agreement signed by General Westmoreland and the commanding general of the Republic of China Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, provided only for essentially political and psychological warfare advisory personnel and prohibited their engagement in combat missions. Second, this new proposal would expose Chinese officers to combat, with the risk of their death or capture, and provide a ready-made situation for Chinese Communist charges of Nationalist Chinese military intervention. Of lesser importance was the fact that the officers' association with US units would disclose their presence to news correspondents. Approval of such a request would also establish a precedent likely to encourage additional Chinese requests for a long-term commitment of more contingents, and might also tempt others to follow Nationalist China's example. The proposal clearly posed serious political risk and military burden to the United States without any tangible benefits.

The State Department agreed with General Westmoreland's appraisal and hoped that the US Military Assistance Advisory Group, Republic of China, and the US Embassy at Taipei would let the matter drop before the State Department had to

[117]

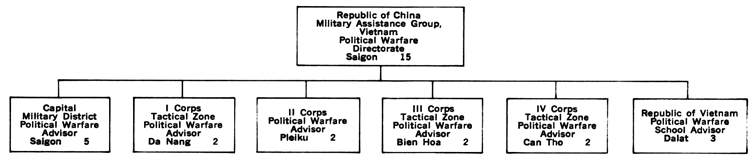

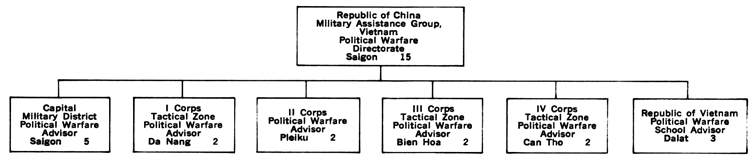

CHART 5 - REPUBLIC OF CHINA MILITARY ASSISTANCE GROUPS, VIETNAM

[118]

reply officially. The Minister of Defense of the Nationalist government explained that the purpose behind the request was to reinforce the combat experience of the armed forces. When the chief of the US Military Assistance Advisory Group, Taipei, presented the reasons behind the US intent to refuse the request, the minister withdrew the proposal.

Arrangements between the governments of the United States and the Republic of China were formalized when USMACV signed a military working arrangement on 19 December 1968 with the Republic of China Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam. Under the agreement Republic of China Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, was controlled and co-ordinated by the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council and command of the group was vested in the military commander designated by the government of the Republic of China. The United States would provide quarters, office space, and transportation within Vietnam.

During the period 1969-1970 the Republic of China assistance group continued to function as before with no significant changes in personnel strength. (Chart 5) After mid-1964, the Chinese group also provided $3 million in economic and technical assistance to Vietnam. As previously mentioned, Chinese technical personnel in the fields of agriculture, electrical power, and medicine were sent to Vietnam, while almost 300 Vietnamese technicians received training on Taiwan. During the Tet offensive of 1968, the Republic of China was one of the first countries to offer assistance, in the form of a gift of 5,000 tons of rice, to meet that emergency situation. In the way of other goods and materials, it provided aluminum prefabricated warehouses, agricultural tools, seeds, fertilizers, and 500,000 copies of mathematics textbooks.

[119]

page created 18 December 2002