CHAPTER VI

The Republic of Korea

In the spring of 1965 when the American Army first sent combat units to Vietnam, the principal threat to the country from the North Vietnamese was in the border areas of the Central Highlands. By July 1965 the North Vietnamese had shown that their main thrust was to come through the highlands, eastward by means of Highway 19, and out to Qui Nhon to split the country into two parts; they would then work from a central area to broaden their control in both northerly and southerly directions.

The critical highlands terrain in II Corps was primarily in Pleiku and Binh Dinh Provinces. Except for major towns, Binh Dinh was completely controlled by the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. The most populated coastal province in the II Corps area, with roughly 800,000 people, Binh Dinh had been dominated by the Viet Cong for many years.

In August 1965, when American troops arrived, Qui Nhon was the only secure town in the province of Binh Dinh. All the highways leading out from Qui Nhon were controlled by the enemy. In Pleiku Province the roads out of Pleiku City were also controlled by the North Vietnamese or the Viet Cong. With the exception of the main towns in II Corps area, all the other communities were threatened and harassed because the enemy controlled routes of travel and communication. Thus, in August 1965 when the Americans began bringing their forces into the II Corps area, the situation was serious in the three major populated areas-the Central Highlands, Binh Dinh, and the Tuy Hoa area to the south of Qui Nhon. A demoralized South Vietnam Army compounded the need for quick, extensive military assistance. This assistance was provided by the United States and Free World countries such as Korea.

In early 1954 the Republic of Korea's President Syngman Rhee offered, without solicitation, to send a Korean Army element to Vietnam to assist in the war against the Communists.

[120]

This proposal was made to Lieutenant General Bruce C. Clarke, ranking U.S. officer in Korea at the time, who relayed it to the Department of State where it was promptly turned down. Korean forces were not sent, nor was there any further action.

Ten years later, in May 1964, Major General Norman B. Edwards, Chief, US Joint Military Advisory Group, Korea, began preliminary planning to send a Korean Mobile Army Surgical Hospital to Vietnam. On 10 July 1964 the Korean Minister of National Defense, Kim Suing Eun, confirmed this planning in a letter to General Hamilton H. Howze, then Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, stating that the government of the Republic of Korea was prepared to send one reinforced Mobile Army Surgical Hospital and ten Tae-kwon-do (karate) instructors to the Republic of Vietnam upon the request of that government. On 16 July 1964, General Howze wrote Minister Kim that in his capacity as chief of the United Nations Command he would concur in the release of such personnel as would be required to staff the mobile hospital and provide the Tae-kwon-do instructors. He further noted that the US Department of Defense would provide logistical support for the movement and continued operation of these deploying forces. The support was to be provided through Military Assistance Program channels in accordance with the applicable procedures of that program. Equipment, supplies, and services to be provided were to include organizational equipment listed in the mobile hospital table of distribution and allowances as approved by Headquarters, Provisional Military Assistance Advisory Group, Korea, beyond the capabilities of the Republic of Korea to provide, and subsistence and clothing for military personnel. Pay, travel, and per diem costs or other allowances for the personnel involved were not to be provided by the United States.

Following these discussions the Republic of Korea Survey (Liaison) Team, which included six Korean and five US officers, departed on 19 August 1964 for Vietnam. After a series of meetings with officials of both the Vietnamese Ministry of Defense and the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, working agreements were signed on 5 September 1964 at Saigon between the Korean and Vietnamese representatives. In essence, the agreements provided that the Republic of Vietnam would build and maintain the hospital and provide quarters; the Korean Army mobile hospital unit would operate the hospital; Korea would provide Tae-kwon-do instructors, and the United States would support the thirty-four officers and ninety-six enlisted men of the hospital unit and the ten instructors through the Mil-

[121]

nary Assistance Program in accordance with Howze's letter to Minister Kim. Accordingly, on 13 September 1964, at the request of the Republic of Vietnam, the Republic of Korea deployed the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital and instructors.

In late December 1964, after a request from the Republic of Vietnam, the Korean government organized an engineer construction support group to assist the Vietnamese armed forces in restoring war-damaged areas in furtherance of Vietnamese pacification efforts. During the period February to June 1965, a Korean construction support group, a Korean Marine Corps engineer company, Korean Navy LST's and LSM's, and a Korean Army security company were dispatched. These elements, totaling 2,416 men, designated the Republic of Korea Military Assistance Group, Vietnam, were better known by their nickname, Dove Unit.

In early 1965, the government of Vietnam, aware that additional assistance was needed to combat the growing Viet Cong pressure, officially asked the Republic of Korea to provide additional noncombatants. The immediate reason for this request was that Vietnamese troops had been diverted to civic action projects related to the heavy flooding during the fall monsoon in 1964. The Korean government agreed that more support could be provided and undertook to supply a task force composed of the commander of the Republic of Korea Military Assistance Group, Vietnam; an Army engineer battalion; an Army transport company; a Marine engineer company; one LST with crew; a security battalion; a service unit; a liaison group, and a mobile hospital (already in Vietnam).

Arrangements for arrival of the Dove Unit were completed by the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council on 6 February. In September a revised military working agreement was signed between the Korean Military Assistance Group and the Vietnam Air Force and on 8 February an arrangement between the commander of the Korean group and General Rosson. The arrangement between the Korean and Vietnamese governments included several unusual features. The Koreans were not to fire unless attacked, but in any event, could not fire on or pursue the enemy outside the area delineated for Korean operations. In case of a Viet Cong attack, the senior Vietnam Army commander in the area would provide assistance. Koreans were not to act against civil demonstrations unless forced to by circumstances and authorized by a Vietnam Army liaison officer. Operational control was not mentioned in these arrangements, although it was implied that in combat action the senior Vietnam Army

[122]

officer would exercise control. The arrangements provided that both MACV and the Vietnam armed forces would provide logistical support for the Korean force. Equipment specified in tables of equipment would be provided through the Military Assistance Program and issued by the Vietnam Army. Maintenance services would be provided by the Vietnam Army. Basic Class I supplies, including rice, salt, tea, sugar, and shortening would be provided by the Vietnam government; supplemental rations and other necessary equipment not available through the Military Assistance Program would be supplied by MACV.

Command and control posed a problem for the three nations involved. At one point, the government of Vietnam stated that it desired full operational control by the appropriate corps commander over all Free World military assistance forces employed in Vietnam. In January 1965 Major General Lee Sae Ho, Senior Korean officer in Vietnam, declared that his government could not accept control by any national authority other than the United States. Using as a precedent the fact that the initial Korean element had been placed under the operational control of General Westmoreland, an agreement was reached whereby the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council was utilized as a combined staff to determine the general operational functions of the Korean force. This council was composed initially of the chief of staff of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, the senior Korean officer in Vietnam, and the chief of the Vietnamese Joint General Staff. Later General Westmoreland took the place of his chief of staff. Various subordinate staffs handled day-today operations. Evidently, the three nations involved found these arrangements to be satisfactory. The military working arrangement between General Rosson and General Lee, signed on 8 February and revised in September, contained provisions which the council used to establish operating limits for the Dove Unit: command would be retained by General Lee, operational control would belong to General Westmoreland, and the force would be responsible to the senior commander in any given area of operations.

On 25 February 1965 the advance element of the Dove Unit arrived, followed on 16 March by the main party. The group was located at a base camp in Bien Hoa and during 1965 constructed three bridges, four schools, two dispensaries, and two hamlet offices, as well as accomplishing numerous other minor projects. Medical elements of the Dove Unit treated some 30,000 patients. In line with recommendations by Westmoreland, the Korean group was increased by 272 officers and men on 27 June and by

[123]

two LSM's (landing ships, mechanized) on 9 July.

Further discussions between the US and Korean authorities on this dispatch of troops soon followed. At a meeting between the Korean Minister of National Defense and the Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, on 2 June 1965, the Korean Minister disclosed that as a result of high-level talks between President Johnson and President Park during the latter's visit to Washington in May 1965 the Korean government had decided to send an Army division to Vietnam. The division, minus one Army regiment but including a Korean Marine regiment, was to be commanded by a Korean Army general. Subsequently, Korea also proposed to send an F-86 fighter squadron to provide combat support for Korean ground elements.

Korean Defense Minister Kim also disclosed that a pay raise for Korean troops had been discussed, and although no firm commitment had been made, the inference was that the United States would help. Because Korea would have one of its divisions in Vietnam, Defense Minister Kim felt that the United States should not continue to entertain proposals to reduce US troop strength in Korea, and instead of suspending the Military Assistance Program transfer project should increase the monetary level of the assistance to Korea. Finally, the minister requested that the United States establish an "unofficial" fund to be administered by Korean officials and used in pension payments to the families of soldiers killed or wounded in Vietnam.

On 23 June 1965 Defense Minister Kim again met with Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, this time in the tatter's capacity as Commander, US Forces, Korea, to discuss the problems connected with the deployment of the Korean division to Vietnam. Before concrete plans could be drawn up, however, the Korean Army needed to obtain the approval of the National Assembly. Although approval was not necessarily automatic, the minister expected early approval and tentatively established the date of deployment as either late July or early August 1965.

The minister desired US agreement to and support of the following items before submitting the deployment proposal to the National Assembly:

1. Maintenance of current US and Korean force ceilings in Korea.

2. Equipment of the three combat-ready reserve divisions to 100 percent of

the table of equipment allowance and the seventeen regular divisions, including

the Marine division, with major items affecting firepower, maneuver, and signal

capabilities to avoid weakening the Korean defense posture.

[124]

3. Maintenance of the same level of Military Assistance Program funding for

Korea as before the deployment of the division.

4. Early confirmation of mission, bivouac area, command channels, and

logistical support for Korean combat units destined for service in Vietnam.

5. Establishment of a small planning group to determine the organization of

the Korean division.

6. Provision of signal equipment for a direct and exclusive communication net

between Korea and Korean forces headquarters in Vietnam.

7. Provision of transportation for the movement of the Korean division and

for subsequent requirements such as rotation and replacement of personnel and

supplies.

8. Provision of financial support to Korean units and individuals in Vietnam,

including combat duty pay at the same rate as paid to US personnel, gratuities

and compensations for line-of-duty deaths or disability, and salaries of Vietnamese

indigenous personnel hired by Korean units.

9. Provision of four C-123 aircraft for medical evacuation and liaison

between Korea and Vietnam.

10. Provision of a field broadcasting installation to enable the Korean

division to conduct anti-Communist broadcasts, psychological warfare, and

jamming operations and to provide Korean home news, war news, and entertainment

programs.

Some years later, in January 1971, General Dwight E. Beach, who had succeeded General Howze as Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, on 1 July 1965, commented on the list.

The initial Korean bill (wish-list) was fantastic. Basically, the ROK wanted their troops to receive the same pay as the Americans, all new US equipment for deploying troops and modernization of the entire ROK Army, Navy and Air Force. I told them with the Ambassador's concurrence that their bill was completely unreasonable and there was no chance whatever of the US agreeing to it. The final compromise included a very substantial increase in pay for the troops deployed, as much good equipment as we could then furnish and a US commitment that no US troops would be withdrawn from Korea without prior consultation with the ROK. The latter, to the Koreans, meant that no US troops would be withdrawn without ROK approval. Obviously, the latter was not the case as is now evident with the withdrawal of the 7th US Division from Korea.

The US Department of State and Department of Defense ultimately resolved the matter of the Korean requirements.

[125]

The request that three combat-ready reserve divisions be equipped to 100 percent of their authorized table of organization and equipment was, the commander of US forces in Korea stated, heavily dependent upon the availability of Military Assistance Program funds. The dispatch of the Korean division to Vietnam might affect Military Assistance Program funds, but whether adversely or not could not be predicted. Under consideration was the possibility of using Korean Military Assistance Program funds to finance the readying and dispatch of the division and for the division's support while it was in Vietnam. Early confirmation of mission, bivouac areas, and other routine requirements was dependent upon information from the Commander in Chief, Pacific. The requirement to provide men for a small planning group to determine the organization of the Korean division met with immediate approval.

The request for signal equipment for direct communication between Korea and the Korean division in Vietnam was not approved. Although high-frequency radio equipment was available, the commander of US forces in Korea, General Beach, felt that a better solution was for the Koreans to use the current US communication system on a common-user basis. The commander agreed that the United States should provide transportation for the division but, depending upon the availability of US shipping, certain Korean vessels might have to be used.

The request for financial support to Korean units and individuals in Vietnam met with disapproval. The US commander in Korea did not favor combat duty pay--especially at the same rate paid to US troops-but was in agreement with the payment of an overseas allowance. If the United States had to pay death benefits or make disability payments, the rates should be those presently established under Korean law on a one-time basis only. The United States would not pay directly for the employment of Vietnamese nationals by Korean forces but was in favor of including such expenses in the agreements between the Republic of Korea and the Republic of Vietnam. Since the request for four C-123 aircraft appeared to overlap a previous transportation request, the commander felt that the United States should provide only scheduled flights to Korea or reserve spaces on other US scheduled flights for Korean use.

At first glance, the request for a field broadcasting installation appeared to conflict with the psychological warfare programs already in operation in Vietnam, but final resolution of the matter would have to await an on-the-ground opinion.

On 13 July 1965 the US State Department authorized the

[126]

US Ambassador to Korea to offer a number of concessions to the Korean government to insure the prompt deployment of the Korean division to Vietnam. The United States agreed to suspend the Military Assistance Program transfer project for as long as the Korean government maintained substantial forces in Vietnam. The United States also agreed to offshore procurement from Korea for transfer items such as petroleum, oil, lubricants, and construction materials listed in the fiscal year 1966 Military Assistance Program. Subsequently, and during the period of the transfer program, the United States would determine offshore procurement from Korea on the basis of individual items and under normal offshore procurement procedures.

These concessions to the Korean government were made, however, with the understanding that the budgetary savings accruing to Korea from the actions taken would contribute to a substantial military and civil service pay-raise for Koreans. Actually, the Korean government would not incur any additional costs in deploying the division to Vietnam but would secure a number of economic benefits. On the other hand, the cost to the United States for Koreans already in Vietnam approximated $2,000,000 annually, and first year costs for the operation of the Korean division in Vietnam were estimated at $43,000,000.

In a later communication on 16 July 1965, the Commander, US Forces, Korea, informed the Commander in Chief, Pacific, of other decisions that had been made in resolving the Korean requests. With respect to the reduction of US force levels in Korea, the US Commander in Korea and the American Ambassador to Korea, Winthrop D. Brown, prepared a letter assuring the Korean government that President Johnson's earlier decision that there would be no reduction in US force levels remained unchanged, and that any further redeployment of US forces from Korea would be discussed with the Korean government officials beforehand.

By August agreement had been reached with the Korean government on the force structure of the division and support troop augmentation, but the military aspects of control and command and the proposed unified Korean headquarters were still under discussion. Consolidated equipment lists for the Korean division, understrength, and the Marine force, as well as the table of allowances for a Korean field support command had been developed and were to be forwarded to General Westmoreland. In logistics, initial and follow-up support of Class II, IV, and V supplies had been settled, but the matter of Class III supplies could not be resolved until information had been received

[127]

from MACV on the availability and receipt of storage for bulk petroleum products. Class I supplies were still under study. A maintenance policy had been worked out for the evacuation of equipment for rebuild and overhaul. All transportation problems had been solved and, finally, training plans had been completed and disseminated. .

Because of the unpredictable outcome of Korean plans to deploy a division to Vietnam and the urgent need to have another division there, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, informed the Commander in Chief, Pacific, through US Army, Pacific, that if deployment of the Korean division did not take place by 1 November 1965, a US Army division would have to be sent to Vietnam instead. Since planning actions for the movement of a division from either the Pacific command or the continental command would have to be initiated at once, the joint Chiefs of Staff asked Admiral Sharp's opinion on the best means of getting a substitute for the Korean division if the need arose.

Admiral Sharp's view was that the two US divisions then in Korea constituted an essential forward deployment force that should not be reduced. Commitment of the 25th Infantry Division to Vietnam-except for the one-brigade task force requested in the event of an emergency-would deplete Pacific command reserve strength at a critical time. Moreover, the 25th Infantry Division was oriented for deployment to Thailand, and if moved to Vietnam should be replaced immediately with another US division. With deployment of the Korean division to Vietnam, the 25th Infantry Division would be available as a substitute for the Korean division in Korea.

On 19 August 1965 the Korean National Assembly, finally passed a bill authorizing the dispatch of the Korean division. The division was to deploy in three increments: the first on 29 September 1965; the second on 14 October 1965; and the third on 29 October 1965. Initial equipment shortages were not expected to reduce the combat readiness of the division.

Definitive discussion between US and Korean authorities on the dispatch of troops began immediately. As a result, the first combat units, the Republic of Korea's Capital (Tiger) Infantry Division, less one regimental combat team, and the 2d Marine Gores Brigade (Blue Dragon) and supporting elements, totaling 18,212 men, were sent during the period September through November 1965.

The Korean government then sought reassurance that sending troops to Vietnam would neither impair Korean defense nor adversely affect the level of US military assistance to Korea. It

[128]

also sought agreements on the terms of US support for Korean troops in Vietnam. Resulting arrangements between the United States and Korea provided substantially the following terms.

1. No US or Korean force reductions were to take place in Korea without prior

consultation.

2. The Korean Military Assistance Program for 1966 was to include an

additional $7 million to provide active division equipment for the three Korean

Army ready-reserve divisions.

3. Korean forces in Korea were to be modernized in firepower, communications,

and mobility.

4. For Korean forces deployed to Vietnam, the United States was to provide

equipment, logistical support, construction, training, transportation,

subsistence, overseas allowances, funds for any legitimate noncombat claim

brought against Republic of Korea Forces, Vietnam, in Vietnam, and restitution

of losses of the Korean force not resulting from the force's negligence.

General Westmoreland also agreed to provide the Korean force with facilities and services comparable to those furnished US and other allied forces in Vietnam. Korean forces in Vietnam had custody of the equipment funded by the Military Assistance Program brought into Vietnam and equipment funded by the Military Assistance Service and provided by General Westmoreland. Equipment funded by the Military Assistance Program that was battle damaged or otherwise attrited was replaced and title retained by the Republic of Korea. In an emergency redeployment to Korea, the Koreans would take with them all equipment on hand. In a slower deployment or rotation, equipment would be negotiated, particularly that held by Koreans in Vietnam but not compatible with similar equipment held by Korean forces in Korea and items extraneous to the Military Assistance Program.

Prior to the arrival of the Korean division, considerable study of possible locations for its deployment took place. The first plan was to employ the division in the I Corps Tactical Zone, with major elements at Chu Lai, Tam Ky, and Quang Ngai; Korean troops would join with the III Marine Amphibious Force, and perhaps other Free World units to form an international Free World force. Subsequently, this idea was dropped for several reasons. First of all, support of another full division in that area would be difficult logistically because over-the-beach supply would be necessary. Deployment of the division in the I Corps Tactical Zone would also necessitate offensive operations since the enclaves were already adequately secured by elements of the III Marine Amphibious Force. Offensive, operations might, in

[129]

turn, provoke problems of "face" between the two Asian republics, Vietnam and Korea, especially if the Korean forces turned out to be more successful during encounters with the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese. There were still several other possible locations at which Korean troops could be stationed. Affecting each of the possibilities were overriding tactical considerations.

The 2d Korean Marine Brigade (the Blue Dragon Brigade) was initially assigned to the Cam Ranh Bay area but did not remain there very long because the security requirements were greater elsewhere. Hence shortly after its arrival the 2d Brigade was moved up to the Tuy Hoa area where the enemy, the 95th Regiment of the North Vietnam Army, had been deployed for several weeks. This enemy unit had been pressing more and more on the population in and around Tuy Hoa and was threatening the government as well as the agriculture of that area.

The Capital Division, affectionately called by the Americans the Tiger Division, arrived at its station about six miles west of Qui Nhon during November 1965, initially with two regiments. The area was chosen, among other reasons, because it was not populated and would therefore not take agricultural land away from the local inhabitants. It was, moreover, high ground that would not be adversely affected by the rains. These circumstances would give the Koreans an opportunity to spread out their command post as much as they wished and allow the first troop units some training in operating against the enemy.

Another reason for not stationing the Capital Division nearer Qui Nhon was that Qui Nhon was to become a major logistic support area, eventually providing the base support for both Korean divisions as well as for the US 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) and the 4th Infantry Division. All the land immediately surrounding Qui Nhon, therefore, was to be used for logistical purposes.

Placed as it was in the Qui Nhon area, the Capital Division would be able to move in several critical directions: it could keep Highway 19 open as far as An Khe; it would be close enough to protect the outskirts of Qui Nhon; it could move northward to help clean out the rice-growing area as well as the foothills to the northwest; and it could move southward on Highway 1 toward Tuy Hoa and assist in clearing out the enemy from the populated areas along both sides of the highway.

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, was sent to the Qui Nhon area prior to the arrival of the Capital Division to insure that the area was protected while the initial Korean units settled down and established camp.

[130]

In early 1966 additional Korean troops were again formally requested by the Republic of Vietnam. Negotiations between the US and Korean governments on this request were conducted between January and March 1966. The Korean National Assembly approved the dispatch of new troops on 30 March 1966, and the Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, concurred in the release of the 9th Infantry Division-the White Horse Division. This unit, which began to deploy in April 1966, brought the strength of the Korean forces in Vietnam to 44,89'7.

The 9th Korean Division arrived in Vietnam during the period 5 September-8 October 1966 and was positioned in the Ninh Hoa area at the junction of Highways 1 and 21. Division headquarters was situated in good open terrain, permitting deployment of the units to best advantage.

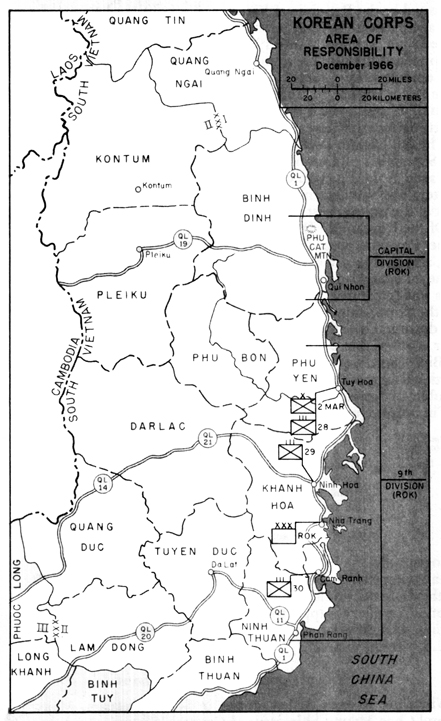

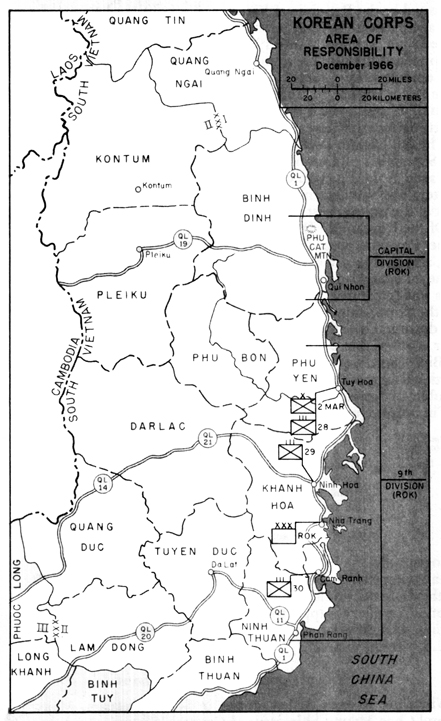

Of the Korean 9th Division the 28th Regiment was stationed in the Tuy Hoa area, the 29th Regiment in and around Ninh Hoa, adjacent to division headquarters, and the 30th Regiment on the mainland side to protect Cam Ranh Bay. With these three areas under control, the 9th Division could control Highway 1 and the population along that main road all the way from Tuy Hoa down to Phan Rang, from Tuy Hoa north to Qui Nhon, and as far north of that city as the foothills of the mountains in southern Binh Dinh Province. (Map 7) A Korean Marine battalion and additional support forces arrived in Vietnam in 1967. In all, the Republic of Korea deployed 47,872 military personnel to Vietnam in four major increments.

| Time Dispatched | Organization | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| 1964- 1965 | Medical and engineer groups (Dove) | 2,128 |

| 1965 | Capital Division (-RCT) with support forces and Marine brigade | 18,904 |

| 1966 | 9th Division with RCT and support forces | 23,865 |

| 1967 | Marine battalion (-) and other support forces | 2,963 |

| 1969 | C-46 crews, authorized increase | 12 |

Logistically, the United States had agreed to support fully the Korean operations in South Vietnam; there never was any doubt that the Koreans would get all the requisite support-the transportation, artillery support, extra engineer support, hospital supplies, food, aviation support, communications support-from the US bases in Vietnam.

Operational Control of Korean Troops

When the Korean Army arrived in South Vietnam, Major General Chae Myung Shin assured General Westmoreland that

[131]

MAP 7 KOREAN CORPS Area of Responsibility December 1966

[132]

whatever mission General Westmoreland gave him he would execute it as if he were directly under Westmoreland's operational control. There was a certain amount of confusion, nonetheless, as to whether the Korean force in South Vietnam would actually come directly under US operational control or whether it would be a distinct fighting force working in close co-ordination with the other allies but under separate control. The confusion was perhaps based on misunderstanding since there never had been a clear-cut agreement between the Korean government and the US government concerning operational control.

On 2 July 1965 General Westmoreland had submitted to Admiral Sharp his views on the command and control organization to be used when a Korean division arrived in Vietnam. If a Korean regiment deployed to Vietnam before the establishment of a field force headquarters, MACV would exercise operational control of both Korean and US units through a task force headquarters located in the II Corps Tactical Zone. When the full Korean division arrived, the division would assume command of the Korean regiment and would come under the direct operational command of the field force headquarters.

General Westmoreland had no objections to a unified Korean command, provided the command was under his operational control and he retained the authority to place the Korean regiment, brigade, or division under the operational control of a US task force headquarters or US field force headquarters. Such an arrangement was necessary so that the US commander would have the authority to maneuver the Korean division or any of its elements to meet a changing tactical situation.

Under this arrangement, noncombatant Korean forces would continue to be under General Westmoreland's operational control through the provisions of the International Military Assistance Policy Council, later designated the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council. Inasmuch as General Westmoreland wanted the commanding general of the Korean division to be free to devote all his energies to tactical matters, he recommended that the Republic of Korea Military Assistance Group, Vietnam, be augmented so that it could assume the responsibilities of a Korean unified command.

After the arrival in Vietnam of the advance planning group for the Korean division and after a series of conferences, new working arrangements were signed between the Vietnamese armed forces and the Commander, Republic of Korea Forces, Vietnam, on 5 September and between General Westmoreland and the Commander of the Korean forces on 6 September. The

[133]

new arrangements contained several interesting features. There was no reference to operational control. The only formally recognized control agency was the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council that continued in its policy-making role. Command, of course, remained with the senior Korean officer.

Since there was no provision for command and control in the military working arrangement signed between General Westmoreland and the commander of the Korean force, General Chae, on 6 September 1965, the policy council prepared a draft joint memorandum indicating that General Westmoreland would exercise operational control over all Korean forces in Vietnam. General Westmoreland presented this proposed arrangement to General Chae and Brigadier General Cao Van Vien, chief of the joint General Staff, on 23 October. At that time, General Chae declared that he could not sign the arrangement without first checking with his government; however, in the interim, he would follow the outlined procedures. The Koreans submitted a revised draft of the command and control arrangement which, after study, General Westmoreland determined to be too restrictive. On 20 November the draft was returned to General Chae, who was reminded that the verbal agreement made on 23 October would continue to be followed.

After additional discussion with General Chae, General Westmoreland reported to Admiral Sharp that a formal signed arrangement could be politically embarrassing to the Koreans because it might connote that they were subordinate to, and acting as mercenaries for, the United States. General Westmoreland felt that a formal arrangement was no longer necessary since General Chae had agreed to de facto operational control by US commanders. Lieutenant General Stanley R. Larsen, Commanding General, I Field Force, Vietnam, and General Chae understood that although directives to Korean units would be in the form of requests they would be honored as orders. It was also thought appropriate that Korean officers be assigned to the field force staff to assist in matters relating to Korean elements. This would not constitute a combined staff as the Korean officers would serve as liaison officers.

There were several logical reasons for the Korean Army in South Vietnam to be constituted as a separate and distinct force. To begin with this was one of the few times in Asian history that a Far Eastern nation had gone to the assistance of another nation with so many forces. It was of great political significance for the Korean government to be able to send its army as an independent force. Many observers felt that the eyes of the world

[134]

would be upon the Koreans and that, as a nation, the Koreans must succeed for the sake of their home country. The Koreans felt much attention would be focused on them to see how well they were operating in conjunction with US forces. If they were working independently, it would show the other countries that not only were the Koreans in a position to act on their own, but they were also freely assisting the United States. The United States could then point out that countries such as Korea, which they had helped for many years, were now operating freely and independently, and not as involuntary props of American policy. Korea's entry into the war in Vietnam showed the world that while Korea was not directly affected by the war it was, nevertheless, willing to go to its neighbor's assistance.

Another reason that the Koreans did not wish to come under de jure US operational control had to do with their national pride. Since Korea had received US assistance for so many years after the Korean War and had followed American tutelage on the organization and leadership of a large armed force, the Vietnam War was an opportunity to show that Koreans could operate on their own without American forces or advisers looking over their shoulders. In effect, the Koreans desired to put into play the military art the United States had taught them.

Assigned to the Qui Nhon area, the Capital Division initially was given the mission of close-in patrolling and spent its first days in South Vietnam getting accustomed to the surrounding terrain and to the ways of the Vietnamese. Though the Koreans and Vietnamese were both Orientals, their languages were completely foreign to each other. They handled people differently; the Koreans were much more authoritative. General Chae attempted to overcome the differences by working with government representatives to establish methods of bringing the Koreans and the Vietnamese together. For instance, the Korean soldiers attended the local Buddhist churches and also repaired facilities which had been either destroyed by enemy operations or suffered from neglect.

The first major operation in the fall of 1965 involving the Capital Division was an effort to protect Highway 19 up to An Khe from just outside Qui Nhon. The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, then stationed in the area, remained in place for about one month and gradually turned over its area of responsibility to the Korean division. Little by little, the Koreans moved into the river paddy area north of Qui Nhon where they en-

[135]

gaged in small patrolling actions and developed their own techniques of ferreting out enemy night patrols.

The Viet Cong quickly learned that the Capital Division was not an easy target for their guerrilla small-unit tactics. Within two months following the Capital Division's entrance into Vietnam, tactical units of the two regiments and the division initially deployed to Vietnam had reached a position nearly halfway between Qui Nhon and Muy Ba Mountain, nicknamed Phu Cat Mountain after the large town to the west of it. The people in that area had been dominated by the Viet Cong for many years. In the process of mopping up the small enemy pockets in the lowlands and rice paddies, military action caused many hardships for the local populace, making it so difficult for them to live that the women and children-and eventually all the pro-government segment of the population-gradually moved out of the area.

By June of 1966 the Capital Division controlled all the area north of Qui Nhon to the east of Highway 1 and up to the base of Phu Cat Mountain. It extended its control also to the north and south of Highway 19 up to the pass leading into An Khe. Working south along Highway 1 down toward Tuy Hoa and within the province of Binh Dinh, the Capital Division sent out reconnaissance parties and carried out small operations as far south as the border between Binh Dinh and Phu Yen.

The Korean Marine brigade, assigned at first to the Cam Ranh Bay area in September and October 1965, was moved to the Tuy Hoa area in December of that year. The reason for the shift was the presence of the 95th Regiment near Tuy Hoa. This regiment, a North Vietnam divisional unit, had disappeared from the western area of South Vietnam and its whereabouts remained unknown for several weeks. It finally showed up in midsummer 1965 in the Tuy Hoa area where it began operations, threatening and dominating the outer regions of the Tuy Hoa area.

Tuy Hoa was a well-populated region, harvesting 60,000 to 70,000 tons of rice a year. The rice paddy land was poorly protected, wide open to control by the Viet Cong and North Vietnam's 95th Regiment. Since the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese utilized the area to supply rice to their own troops all the way up to the Central Highlands, the rice land had become a strategic necessity for the enemy. During the summer of 1965 the North Vietnamese 95th Regiment gained control of more and more of the rice production and by the middle of the wet season, October and November, a crisis had developed. The morale of

[136]

KOREAN MARINES PREPARE DEFENSIVE POSITIONS TEAR TUY HOA

[137]

the people had sunk to a dangerous low; something had to be done soon, not only to protect the local inhabitants but also to assure them that protection would continue. The Korean Marine brigade therefore was moved from Cam Ranh Bay to the Tuy Hoa area.

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, meanwhile having completed its assignment to protect the higher perimeter around Qui Nhon until the Capital Division was settled, moved down to the Tuy Hoa area and began probing for the enemy. When the Korean brigade moved to the Tuy Hoa area, the two brigades, US and Korean, worked side by side for several weeks, but at Christmas 1965 the 1st Brigade of the 101st Division moved south to Phan Rang, its home base, leaving the entire Tuy Hoa area to the Korean brigade.

After the 9th Korean Division arrived in South Vietnam, General Westmoreland recommended that General Chae develop a corps headquarters in Nha Trang adjacent to that of the US I Field Force. When the Korean corps headquarters was established and became operational in Nha Trang during August 1966, General Chae decided that he should also establish a headquarters in Saigon and wear a second hat as commander of all Korean troops in Vietnam, representing the Korean government on an equal basis with the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

There were obvious command and control reasons for establishing the Korean corps headquarters in Nha Trang close to I Field Force. Inasmuch as the Koreans now had more than 50,000 troops in the area, the South Vietnamese two and one half divisions in II Corps, and the Americans two full divisions and a brigade in Vietnam, the Korean corps headquarters facilitated liaison between allied forces. Since there had to be close coordination with the Koreans in logistical as well as tactical matters, there had to be close understanding between the two corps headquarters on planning new missions and guaranteeing the kind of support, both tactical and logistical, required to sustain the Korean fighting forces wherever they were conducting operations.

The operation and coordination of the Korean corps alongside I Field Force in Nha Trang tied in very closely with the operations of the Americans. By mutual agreement the two staffs were in continuous contact with one another. The operations officers of the I Field Force and the Korean corps met four or five times a week, and intelligence officers from both commands interchanged information. There was no requirement to effect

[138]

FIELD COMMAND HEADQUARTERS of Republic of Korea Force, Vietnam, at Nha Trang.

any administrative co-ordination. Logistically, however, the Koreans had close liaison with the I Field Force logistics staff officers by whom logistics support requirements for impending operations were verified.

One of the more important relationships developed by the U.S., Korean, and South Vietnam corps commanders in the II Corps area was in planning future operations. These had to be worked out weeks in advance with General Vinh Loc, commander of the Vietnam II Corps; General Larsen, commander of the US I Field Force; and General Chae, commander of the Korean corps. Every six months the three commanders, with their staffs, co-ordinated the next six months of operations and campaign strategy. There was never any conflict with respect to areas of major responsibility. Only the timing and kind of support, both in weaponry and in helicopters, for the planned operations had to be worked out.

It was through this working arrangement that one of the major campaigns of the war took place in Binh Dinh Province in September 1966. The Capital Division, commanded by the young and extremely capable General Lew Byong Hion, worked

[139]

out the details with the commanding general of the 1st Cavalry Division, Major General John Norton, and General Nguyen Van Hieu of the 22d Vietnam Division, with headquarters in Qui Nhon.

The tactical agreement among the three division commanders was that at a given time the 1st Cavalry Division would move north out of An Khe and then, in a southerly sweep of the area north of Phu Cat Mountain, pin down the area and search it for any enemy activity involving the 2d Viet Cong Regiment, the 18th North Vietnamese Regiment, and portions of the 22d North Vietnamese Regiment, all under the command of the North Vietnam 3d Division with headquarters north of Bong Son. The Koreans would move north, sweeping all of Phu Cat Mountain, and occupy the strip along the ocean north of the mountain while elements of the 22d Vietnamese Division would move between the Koreans and US troops from Highway 1 toward the sea.

In a succession of rapid movements up Phu Cat Mountain, the Koreans rapidly occupied key points of the terrain and in a matter of a few days had completely dominated an area occupied by at least two North Vietnamese battalions. The drive on Phu Cat Mountain by the Korean forces was extraordinarily thorough and effective. The count of captured weapons alone amounted to more than 600 rifles.

By the end of 1965 the Korean corps under General Chae, who had been promoted from commanding general of the Capital Division to commander of the corps, had assumed responsibility all the way from Phu Cat Mountain down to Phan Rang. The tactical area of operations included the mission of protecting all the populated area on each side of Highway 1. With the exception of the northern third of Phu Yen Province between the northernmost brigade of the Korean 9th Division in Tuy Hoa and the Capital Division in Binh Dinh Province, where the 1st Brigade of the US 101st and elements of the US 4th Division were brought in to fill the gap in early and mid-1966, the entire area had become the responsibility of the Koreans, working in conjunction with the South Vietnamese Army whenever they were in the same area.

Another example of the Koreans' capability in small unit tactics was the coordination between I Field Force headquarters and General Chae that provided a Korean battalion in the Central Highlands to work with the US 4th Infantry Division south of Highway 19, just east of the Cambodian border. When the battalion arrived it was divided into three separate company

[140]

outposts and embarked on operations involving small unit patrols in all directions from each of the base camps.

On the sixth night after arrival of the Koreans in the highlands, a battalion of North Vietnamese (believed to be a battalion of the 101st North Vietnamese Regiment) attacked the northernmost company at night. In a succession of close combat actions the North Vietnamese tried for several hours to break into the company area, but they were repulsed at each attempt. When the next morning dawned, the Koreans had lost only seven men and had killed, by actual count, 182 of the enemy, exclusive of the number of bodies and other casualties dragged away. The Korean company was assisted by three US Army tanks, and the American tankers had endless praise for the Koreans in this action.

The Korean contribution to the war in Vietnam may, in a large measure, be summed up by a description of the type of soldier sent from the Land of the Morning Calm. President Park insisted that only volunteers be sent to Vietnam. Since a vast number of soldiers volunteered to go with their Army to South Vietnam, commanders were able to handpick the men they wished to accompany their units. The tour of duty was one year, but if the soldiers did not live up to the high standards established by the Korean Army, they were to be sent home from the combat area immediately.

The units selected had the longest service and the best records in the Korean War. According to the Korean Army military historians, these units were selected on the basis of their heritage (decorations and campaigns), mission, and location. The Korean Capital (Tiger) Division was ideal since it was one of the Korean Army's most famous divisions. It was also a Korean Army first reserve division, and its removal therefore had less effect on the frontline tactical situation in Korea than would the withdrawal of divisions in the lines. Furthermore the terrain in the division's former area approximated the terrain in Vietnam. The 9th (White Horse) Division was chosen because it, too, was a renowned fighting unit and did not occupy a critical frontline position at the time of its selection. The United States had no direct veto on the units selected. Although concurrence of the Commander in Chief, United Nation's Command, was solicited and received, the units were selected unilaterally by the Korean Ministry of National Defense.

Since this was the first time in modern history that Korean soldiers would serve abroad, Korean military leaders wanted to put their best foot forward. This national position produced a

[141]

soldier who was highly motivated, well trained, and well disciplined; each individual Korean trooper appeared to speak well for the ambitions and discipline of the Korean Army by his tactical ability and his conduct as a personal representative of his country in a foreign combat zone.

The entire Korean Army was screened and many of its finest officers and men were assigned to the Korean Capital Division. Almost all of the combat arms' junior officers were graduates of the Korean Military Academy. Each officer was handpicked by senior Capital Division officers. A complete replacement of the division staff was accomplished within the first few days of activation. An after action report of 26 November 1965 gave the method used.

Since the Capital Division was a reserve division within a reserve corps and therefore had a very low priority with respect to all personnel actions, more than ninety percent of the personnel had to be replaced to comply with the high standards for assignment. The result was that a large number of highly skilled personnel were transferred from units within First ROK Army to fulfill the requirement. In order to insure that an imbalance among levied units did not occur as a result of this action, a directive was sent to each combat division which equitably distributed the levy of critical MOS's. Approximately 500 personnel were obtained from each division. Unit replacement into the receiving unit, at squad and platoon level, was accomplished by this action.

Enlisted men were given inducements to serve in the division. They would receive credit for three years of military duty for each year served in Vietnam as well as additional monetary entitlements; further, combat duty would enhance their future Army careers. Similar procedures and benefits applied to the 9th (White Horse) Division as well.

President Park Chung Hee personally selected such senior officers as General Chae. Chae was a good man in Korea and, considering his instructions from his president, did as well if not better than anyone else the Korean government could have sent. It is believed that if General Chae had been under US operational control, all Americans who had official contact with him would have sung his praises. As it was, he had the difficult job of pleasing his government at home and staying on somewhat good terms with the Americans as well.

It is of considerable interest to compare the Koreans as the Americans had known them in the Korean War with the Koreans as they operated in combat in South Vietnam. In Korea they had leaned heavily upon the Americans for competent advice in most fields of tactical support. In Vietnam, it may be unequivo-

[142]

cally stated, the Korean forces handled themselves with proven competence in both tactical and tactical-support operations as well as in logistics, including engineering and medical administration. It was a source of pride to those Americans who had been dealing with the Koreans over the years to observe the independence and self-confidence displayed at every turn by the Korean commanders and troops in Vietnam. The Koreans had been primarily taught to act defensively, that is to fight in the defense of their own country. It was assumed they would fight defensively in South Vietnam. The Korean actually is an aggressive soldier when provided the opportunity to prove his mettle. While many Korean missions were undertaken to protect the indigenous population, the Korean soldier and his immediate leader-his sergeant, his lieutenant, his company commander-were extremely aggressive in their pursuit of the enemy. Some differences between American and Korean troops were probably due to the fact that early in the Vietnam War US troops had been taught to make full use of the helicopter. The Americans had extensive logistical support and, in addition, had a much larger area of tactical operations. There was a derivative requirement that American troops be able to move from one area to another quickly in order to meet the enemy wherever it was suspected he might be located. The Koreans, on the other hand, had a set area more or less tied to the local population, a circumstance that required the Koreans to be more careful of the manner in which they handled themselves tactically in searching out the enemy. The Koreans had slightly different missions, too, one of which was to keep the roads and Highway 1 open and to protect the local people at whichever point they made contact with them.

The Koreans were thorough in their planning and deliberate in their execution of a plan. They usually surrounded an area by stealth and quick movement. While the count of enemy killed was probably no greater proportionately then that of similar US combat units, the thoroughness with which the Koreans searched any area they fought in was attested to by the fact that the Koreans usually came out with a much higher weaponry count than US troops engaged in similar actions.

Since all of the senior Korean officers and many of the junior officers spoke excellent English, they had no difficulty in communicating with the Americans, and their understanding of US ground tactics made it easy for the forces of the two nations to work together.

Although support was available to them, the Koreans showed

[143]

KOREAN TROOPS USE CHART to show villagers types of Viet Cong booby traps.

remarkable ingenuity in handling many of their requirements with a minimum of equipment. With the Koreans the overriding premise that things should get done precisely when they were needed required the individual to use substitute methods when necessary, whether the job be building bridges, building houses and covering them with watertight roofs, or creating comforts for themselves out of materials their American brothers could not imagine using productively. For example, the Koreans used ammunition boxes to build windows, doors, and even frame houses. Cardboard ration boxes were overlapped and used as roof shingles. These shingles would last for many months and during monsoon weather when they wore out there always seemed to be a good supply of replacements on hand. When new bases were established, in no time at all the Koreans would have two, three, or four men to a hut, enjoying as much if not more comfort than their American counterparts. It was quite obvious to any visitor arriving in a Korean bivouac area that the Korean soldier took pride in his job and in handling his personal needs and wants.

[144]

One of the most noteworthy assets of the Korean troops was their discipline; it was immediately clear that Korean soldiers were well prepared, trained, and dedicated. Each regiment arrived, established base camps, and immediately went out on training missions which, in turn, led to combat missions under its capable officers. Korean discipline is a self-discipline, an inner discipline; a sense for self-preservation serves as a spark to generate initiative to get out of any predicament the Korean soldier may find himself in when his leaders are not around. Another indication of his discipline, and his fierce pride, is his personal appearance. Rarely could one find a Korean soldier who did not appear immaculate, whether he was assigned to an administrative or a combat area.

In any assessment of the Koreans' contributions in South Vietnam it must be underlined that they provided the man-to-man equivalent of the Americans in that Southeast Asian country. In other words, every Korean soldier sent to South Vietnam saved sending an American or other allied soldier. The Koreans, who asked for very little credit, have received almost no recognition in the US press and it is doubtful if many Americans fully appreciate their contributions in South Vietnam. In addition to saving roughly 50,000 US troops from being deployed to South Vietnam, the Koreans provided protection to the South Vietnamese for a distance of several hundred miles up and down the coast, preventing a renewal of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong harassment and domination.

In mid-January 1966 when General Westmoreland was asked to evaluate the Korean forces then in Vietnam, he indicated that for the first two or three months after their arrival Korean senior commanders had closely controlled the offensive operations of their forces in order to train their troops for combat in their new environment. This policy had given the impression that the Koreans lacked aggressiveness and were reluctant to take casualties. In Operation FLYING TIGER in early January of 1966, the Koreans accounted for 192 Viet Cong killed as against only eleven Koreans. This feat, coupled with Korean success in Operation JEFFERSON, constituted a valid indication of the Koreans' combat effectiveness.

The Koreans had an initial period of difficulty in their relations with the Vietnamese military forces because they were better equipped than the troops of the Vietnamese Army and those of the Regional Forces and Popular Forces, because of language barriers, and because of the Oriental "face" problem. The attitude of the Vietnamese Army quickly changed, however, and its

[145]

appraisal of the Korean forces appears to be essentially the same as the US evaluation. The Koreans had much in common with the Vietnamese public in areas where they were stationed because of the common village origin of the Korean soldier and the Vietnamese peasant, the common rice economy of the two countries, and their similarities in religion and rural culture.

The Koreans remained independent and administratively autonomous. In handling disciplinary matters arising with Vietnamese citizens and the Vietnam government, for example, the Koreans used their own military police and accepted full responsibility for their troops. They handled untoward incidents independently. Military police courtesy patrols in areas of overlapping American, Vietnamese, and Korean responsibility were formed with representatives of each of the three countries.

The size of the Korean force was determined piecemeal and was based solely on what the United States thought was possible from the Korean point of view and on what the United States was willing to pay. Military requirements had very little to do with it. The United States negotiated first for a one-division force. After it was in Vietnam, completely new negotiations to increase the force to a two-division-plus corps were begun. With the second negotiations, the cost to the United States went up, with the Koreans trying to get the maximum out of the Americans. Each major unit was considered separately.

In summary, a formal agreement on the use and employment of the Koreans did not exist. At first General Westmoreland told the I Field Force commander the Koreans would be under his control. The Capital Division commander, General Chae, on his first visit to I Field Force made clear that he did not consider himself under US control. After the second Korean division and the Marine brigade arrived and a Korean corps took over, with General Chae commanding, the Koreans were independent of I Field Force. Operations, however, were coordinated in an amiable spirit. The Koreans had specified their desire to be deployed in a significant, prestigious area, on the densely populated coast, where the Korean presence would have the greatest impact at home and abroad. The Koreans were also under instructions to avoid heavy casualties.

President Park, during his visit to the Republic of Vietnam, had told General Westmoreland that he was proud to have Koreans fight under Westmoreland's command. This verbal statement was as far as any admission of subordination of Korean forces to US command ever went. General Westmoreland told the commander of I Field Force to work out an arrangement on

[146]

KOREAN SOLDIERS SEARCH THE JUNGLE NEAR QUI NHON FOR VIET CONG

the basis of letting "water seek its own level." Relationships and co-operation were good, but required diplomacy and tact. The Koreans gradually spread out over large coastal areas and pacified the people. Persuasion to follow US suggestions appears to have been necessary at times. The Koreans believed they were specially qualified to work with the indigenous population because of their common background as Asians.

Results of Korean Combat Operations

The success of the Korean Army and Marine forces in Vietnam was exemplified by the numerous casualties inflicted on the enemy and the very high kill ratio enjoyed by the Korean forces. In addition the large number of weapons and the amount of materiel captured as well as the serious disruptions of the Viet Cong organization in the Koreans' tactical area of responsibility attest to, in the words of General Westmoreland, "the high morale, professional competence, and aggressiveness of the ROK soldier." He went on to say that reports were "continually received on the courage and effectiveness of all ROK forces in South Vietnam."

[147]

Following Operation OH JAC KYO in July 1967 the Korean 9th and Capital Divisions thwarted enemy intentions to go on the offensive in Phu Yen Province by inflicting large troop and equipment losses primarily on the North Vietnamese 95th Regiment. Operation HONG KIL DONG alone accounted for 408 enemy killed and a kill ratio of 15 to 1 between 9 and 31 July. By the time the operation was terminated on 28 August, in order to provide security for the coming elections, the total enemy killed had reached 638 and the kill ratio was 24 to 1. In addition, some 98 crew-served and 359 individual weapons had been captured.

In the last four months of 1967, however, no major Korean Army operations were undertaken. This was due partly to the need to provide security for the South Vietnamese elections of September in the face of increased enemy attempts to thwart those elections and partly to the need to keep more than 350 kilometers of Highways 1 and 19 "green." Small unit actions continued to be numerous.

During 1968 the pattern of Korean operations did not change materially from that of previous years; the Korean troops continued to engage in extensive small unit actions, ambushes, and battalion and multi-battalion search and destroy operations within or close to their tactical areas of responsibility. Over-all these operations were quite successful. An analysis of an action by Korean Capital Division forces during the period 2329 January 1968 clearly illustrates the Korean technique. After contact with an enemy force near Phu Cat, the Koreans "reacting swiftly . . . deployed six companies in an encircling maneuver and trapped the enemy force in their cordon. The Korean troops gradually tightened the circle, fighting the enemy during the day and maintaining their tight cordon at night, thus preventing the enemy's escape. At the conclusion of the sixth day of fighting, 278 NVA had been KIA with the loss of just 11 Koreans, a kill ratio of 25.3 to 1."

Later in 1968 a Korean 9th Division operation titled BAEK Ma 9 commenced on 11 October and ended on 4 November with 382 enemy soldiers killed and the North Vietnamese 7th Battalion, 18th Regiment, rendered ineffective. During this operation, on 25 October, the eighteenth anniversary of the division, 204 of the enemy were killed without the loss of a single Korean soldier.

By and large, however, the Korean Army continued to stress small unit operations. In its operational assessment for the final quarter of calendar year 1968, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Quarterly Evaluation states:

As the quarter ended Allied forces in II CTZ were conducting ex-

[148]

tensive operations throughout the CTZ to destroy enemy forces and to provide maximum possible support to the Accelerated Pacification Campaign. The prime ingredient in the overall operation was small unit tactical operations. For example, as the Quarter ended . . . ROK forces were conducting some 195 small unit operations.

This Korean emphasis was in keeping with the policy in the II Corps Tactical Zone of economy of force in the first quarter of calendar year 1968 and the greater stress on effective defense of cities and installations.

The primary effort in the II Corps Tactical Zone during the first three months of 1969 was directed toward pacification and improvement of the effectiveness of the armed forces of the republic. The Koreans continued to maintain effective control of the central coastal area from Phan Rang in Ninh Thuan Province to the north of Qui Nhon in Binh Dinh Province. All allied forces found enemy base areas and supply caches with increasing frequency. Binh Dinh Province continued to lead all other provinces in number of enemy incidents; however, the majority of reported actions were small unit contacts with generally minor results. Allied units, particularly the Korean force, continued to place great emphasis on small unit operations. The enemy continued to avoid decisive engagements and directed his activity mainly against territorial forces and civilian population centers.

An analysis of Korean cordon and search operations was provided by Lieutenant General William R. Peers, who considered the Koreans to have more expertise in this kind of operation than any of the other forces he had seen in South Vietnam:

There were several key elements in their conduct of this type of operation. First, they are thorough in every detail in their planning. Secondly, their cordon involves a comparatively small area, probably not in excess of 9 to 10 square kilometers for a regimental size force. Third, the maximum force is employed, generally consisting of a regiment up to something in excess of a division. And finally, the operation is rehearsed and critiqued before it is begun. Units are moved into locations around the periphery of the cordon by a variety of means, including helicopters, trucks and by foot, but so limed that all arrive in position simultaneously to complete the encirclement. The density of the troops is such that the distance between individuals on the cordon is less than 10 meters. They leave little opportunity for the enemy to ex-filtrate in small numbers. Areas, such as streams and gulleys, are barricaded with barbed wire and other barrier materials, reinforced by troops who may remain in water chest deep over night. The closing of the cordon is very slow and deliberate, not a rock is left unturned or piece of ground not probed. When the area has been cleared, they will surge back and forth through it to flush out any of the remnants. An-

[149]

other critical feature of their operation is the availability of reaction forces. The enemy soon knows when such a cordon is put around him. If he cannot ex-filtrate by individuals or in small numbers, he may attempt to mass his forces and break out at one point. Against such contingencies the ROK's utilize several reaction forces to reinforce critical areas. They have found that the enemy may make one or even several feints at various points around the cordon prior to making the main effort to breach the encirclement. Hence, the ROK deployment of reaction forces is by small incremental elements until such time as the main effort is located, and then the action becomes rapid and positive. Through the use of these tactics, the ROK's have developed the cordon and search operation to a fine state of art. The ratio of enemy to friendly casualties has been phenomenal-on one occasion in excess of 100 to 1.

Generally Korean large-scale operations during 1969 were of regimental size or less, of brief duration, and with a specific target. One significant operation of this kind was Dong Bo 7, carried out near Cam Ranh from 9 to 11 May 1969. Soldiers of the 2d Battalion, 30th Regiment, 9th (White Horse) Division were airlifted onto Tao Mountain, a base for units of the 5th North Vietnam Army Division, and searched the caves and trenches on the mountain. Wizen the operation ended, 155 enemy soldiers had been killed while the Koreans had three killed and one wounded.

Throughout 1970 the Koreans continued to conduct many operations of short duration aimed at supporting the over-all pacification program and the general campaign goals. The Korean Army division conducted an average of 150 small unit actions each day, including ambushes, search and clear operations, and the normal efforts to secure the areas around minor installations. The major results of Korean efforts were reflected in the infrequent larger scale operation of the Koreans; however, their kill ratio remained high for all operations.

Every time the Koreans performed a mission they did it well. A study of the tactical area of responsibility assigned them shows clearly that they were stretched to the limit geographically, with the job of keeping the roads open from above Phu Cat north of Qui Nhon all the way to Phan Rang down in Ninh Thuan, three provinces below Binh Dinh. They had several hundred road miles of responsibility-and they kept the roads open.

The enemy feared the Koreans both for their tactical innovations and for the soldiers' tenacity. It is of more than passing interest to note that there never was an American unit in Vietnam which was able to "smell out" small arms like the Koreans. The Koreans might not suffer many casualties, might not get too

[150]

many of the enemy on an operation, but when they brought in seventy-five or a hundred weapons, the Americans wondered where in the world they got them. They appeared to have a natural nose for picking up enemy weapons that were, as far as the enemy thought, securely cached away. Considered opinion was that it was good the Koreans were "friendlies."

Evaluation of Korean Operations

Evaluation by senior US officers of Korean operations during the period of the Koreans' employment in Vietnam tended to become more critical the longer the Koreans remained in Vietnam. Of several factors contributing to this trend, three were more significant than the others. First, the US commanders expected more of the Koreans as they gained experience and familiarity with the terrain and the enemy. Second, the Koreans persisted in planning each operation "by the numbers," even though it would appear that previous experience could have eliminated a great deal of time and effort. Third, as time went on the Korean soldiers sent to Vietnam were of lower quality than the "cream of the crop" level of the entire Korean Army which first arrived.

General Larsen's successor as Commanding General, I Field Force, Vietnam, General William B. Rosson, in his "End of Tour Debriefing Report" presented a number of insights into the problems of establishing effective teamwork between Korean and US and Korean and Vietnam forces. General Rosson stressed the "extraordinary combination of ROK aspirations, attitudes, training, political sensitivities and national pride" which culminated in the Korean characteristics of restraint and inflexibility that many US officers found so difficult to comprehend and to deal with. Rosson's experience led him to employ "studied flattery," which he used liberally and with success in establishing productive rapport, "but never to the point of meting out undeserved praise."

In addition General Rosson found certain other techniques in dealing with the Korean authorities: occasional calls on Korean officials junior to himself; encouragement of staff level visits between US and Korean unit headquarters; combined US Korean conferences on a no-commitment basis to consider subjects of common interest; planning and conduct of combined operations; fulfillment of Korean requests for support whenever possible; visits to Korean units during combat operations; personal, face-to-face requests for assistance from the Koreans.

One of these techniques-fulfillment of Korean requests

[151]

whenever possible-has been challenged by later commanders. One other-planning and conduct of combined operations-has been one of the chief sources of criticism of the Koreans, who are very reluctant to enter into truly combined operations.

General Peers, who succeeded General Rosson, stated that it took some learning and understanding but that he found the Koreans highly efficient and a distinct pleasure to work with. He also stated that every effort was made to support Korean operations by providing additional artillery, helicopters, APC's, and tanks and that this practice proved of immense value in developing co-operation between the Koreans and adjacent US units.

A slightly different point of view was provided by Lieutenant General Arthur S. Collins, Jr., who was Commanding General, I Field Force, Vietnam, from 15 February 1970 through 9 January 1971. General Collins stated that the Koreans made excessive demands for choppers and support and that they stood down for too long after an operation. He equated the total effort from the two Korean divisions to "what one can expect from one good US Brigade."

General Collins, for the first eight months of his time, followed the policy of his predecessors in that he went to great lengths "to ensure that the ROK forces received the support they asked for." He felt that it was in the interest of the United States to do so. His final analysis, however, was that this was a mistake in that in spite of all-out support the Koreans did not conduct the number of operations they could and should have. He felt that a less accommodating attitude might have gained more respect and cooperation from the Koreans but did not venture to guess whether such a position would have made them any more active.

General Collins' successor, Major General Charles P. Brown, deputy commander and later commanding general of I Field Force, Vietnam, and commanding general of the Second Regional Assistance Command during the period 31 March 197015 May 1971 made this statement:

The ROK's spent relatively long periods planning regimental and division sized operations, but the duration of the execution phase is short.

The planning which leads to requests for helicopter assets to support airmobile operations is poor. This assessment is based on the fact that the magnitude of their requests for helicopters generally is absurdly high. Without disturbing their tactical plan one iota, their aviation requests can always be scaled down, frequently almost by a factor of one-half . . . .

[152]

Execution is methodical and thorough, and there is faithful adherence to the plan with little display of the ingenuity or flexibility that must be present to take advantage of tactical situations that may develop. In other words, reaction to tactical opportunities is slow, and this is true not only within their own operations, but also is true (to an even greater degree) when they are asked to react for others.

In terms of effort expended, they do not manage as many battalion days in the field as they should, yet they are loath to permit others to operate in their TAOR.

In summary, however, General Brown stated that "while the preceding tends to be critical, the facts are that results (especially when one considers the relatively short amount of time devoted to fighting are generally good, and this is what counts in the end."

Other senior officers noted the great political pressure the Seoul government placed on the Korean commander and its effect on Korean military operations. Since the Korean government was not fully attuned to the changing requirements of the ground situation, its policy guidance often hampered the optimum utilization of Korean resources. Specifically this resulted at times in a strong desire on the part of the Koreans to avoid casualties during periods of domestic political sensitivity as well as sudden changes in their relations with the people and government of South Vietnam.

General Creighton Abrams has indicated that from a purely professional point of view the Koreans probably outperformed all of our allied forces in South Vietnam. In response to a question from Vice President Spiro T. Agnew regarding the performance of the Koreans in comparison with the Vietnamese, General Abrams made this statement:

There were some things in which the Koreans, based purely on their professionalism, probably exceeded any of our allied forces in South Vietnam. An example of this would be when they decided to surround and attack a hill. A task of this sort would take one month of preparation time during which a lot of negotiating would be done to get the support of B-52's, artillery and tanks. Their planning is deliberate and their professional standards are high. The Korean planning is disciplined and thorough. In many other fields, however, particularly in working close to the population, the Vietnamese show much more sensitivity and flexibility than the Koreans. In short, the kind of war that we have here can be compared to an orchestra. It is sometimes appropriate to emphasize the drums or the trumpets or the bassoon, or even the flute. [The] Vietnamese, to a degree, realize this and do it. The Koreans, on the other hand, play one instrument- the bass drum.

[153]