- Chapter II:

Organizing the Assistance Effort

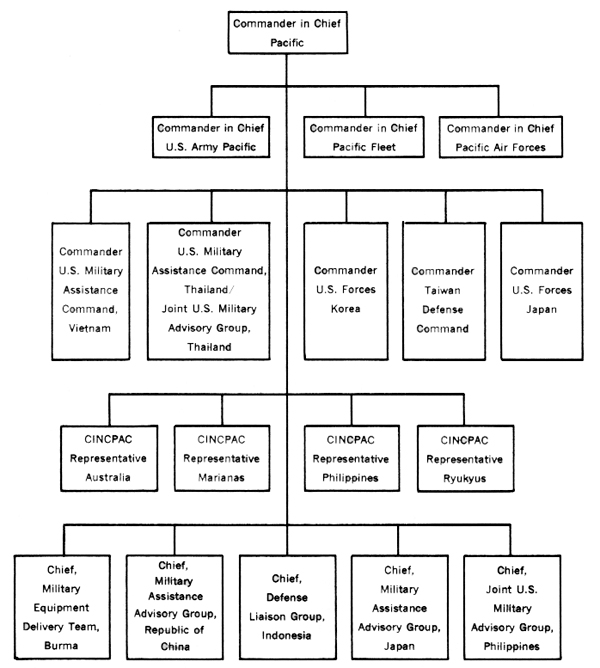

Since the inception of the United States Military Assistance Command,

Vietnam, on 8 February 1962, its policies, organization, and objectives

were guided by staff contingency planning for the entire Southeast Asia

area. The chain of command from Military Assistance Command headquarters

in Saigon to Pacific Command headquarters in Hawaii was established

primarily at the insistence of Admiral Harry .D. Felt, Commander in Chief,

Pacific, who strongly believed that only Pacific Command with its joint

Army, Navy, and Air Force staff could effectively and dispassionately deal

with the entire Southeast Asia area. For this reason the staff and

planning capabilities at Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), were

limited. Contingency and long-term operational planning for Southeast Asia

were to be conducted from the headquarters having cognizance of the entire

Pacific theater. Furthermore, the disrupted political and military

situation had not been accurately appraised. It was thought that the

insurgency problem could be brought under control in short order and that

a temporary MACV headquarters incorporating the old Military Assistance

Advisory Group (MAAG) as an operating headquarters would prove adequate

for handling operations until the emergency passed and the Military

Assistance Advisory Group could resume its normal functioning. (Chart 1)

General Paul D. Harkins, as the first Commander, U.S. Military

Assistance Command, Vietnam (COMUSMACV), was responsible for performing

the functions of the chief of the old military advisory group and in that

capacity acted as senior adviser to the Republic of Vietnam's armed forces

while also commanding the Army component of the combined services'

Military Assistance Command. The commanding general of the U.S. Army

Support Group, Vietnam, which had been formed in 1961 to provide

administrative and logistic support for Army forces in Vietnam, became the

deputy Army component commander. General Harkins therefore exercised

operational control of Army forces, while the commanding general of

Support Group, Vietnam, was responsible for administrative and logistic

support.

[13]

The Military Assistance Advisory Group was finally absorbed intact by

the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in 1964. The air and naval

advisory activities and their personnel were subordinated to the

corresponding component commands of the Military Assistance Command.

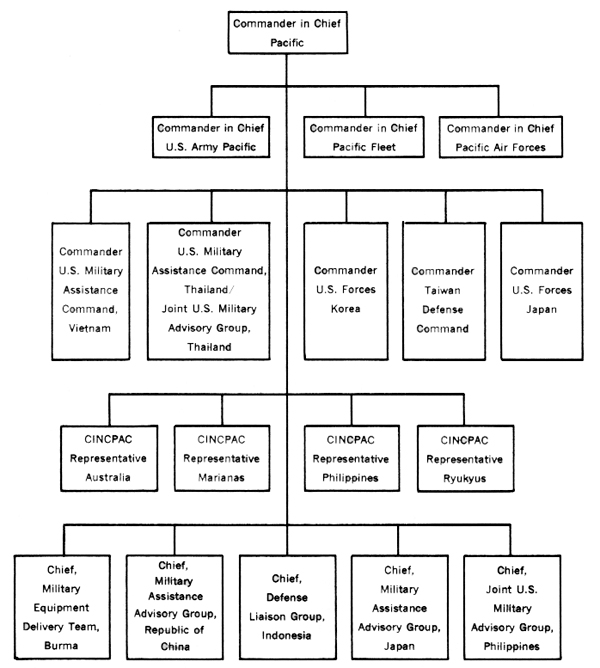

General Harkins as COMUSMACV was succeeded on 20 June 1964 by General

William C. Westmoreland, who continued to direct actively only Army

component activities while providing general guidance to the other

participating services. Shortly after General. Westmoreland assumed

command, the U.S. force buildup completely outpaced the existing support

system, and in April 1965 the 1st Logistical Command was deployed and sub-

[14]

sequently assigned to the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam. (Chart 2)

When President Lyndon B. Johnson was given the mandate of Congress to

commit U.S. troops in August of 1964, and the decision was made to do so

on a large scale, it became apparent that a review of the command and

control structures would be necessary. The major issues concerned MACV's

status as a subordinate unified command under orders from Pacific Command

headquarters, MACV's working relations with the Vietnamese military and

arriving allies, and MACV's U.S. troop command authority.

The same argument Admiral Felt voiced in 1962 was raised

[15]

again in 1965, this time by the new Commander in Chief, Pacific, Admiral

U. S. Grant Sharp. The military threat in the Pacific was not limited to

Vietnam and action there could not, therefore, be conducted without regard

for operations and plans for Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Laos,

Thailand, or any other Pacific area. Military Assistance Command would

remain subordinate to Pacific Command (PACOM) headquarters, and General

Westmoreland could direct his attention to Vietnam exclusively.

The second issue under consideration, MACV's relationship with the

Vietnamese armed forces, was still more sensitive. A single joint command

under an American commander hinted too strongly of American colonialism;

therefore command would devolve into co-operation and co-ordination

between U.S. and Vietnamese forces. The question of the operational

control of _U.S. Army forces involved both military and political

considerations.

To provide administrative control of and support for the combat forces,

the U.S. Army Support Command was transformed into the U.S. Army, Vietnam

(USARV), on 20 July to carry out "all the functions of a field army

save those an Army commander would perform at a forward command

post." Military Assistance Command would carry out the tactical

functions. The establishment of USARV made a headquarters available with

the personnel and other resources required to control all Army activities.

An Army component headquarters, exercising operational control over land

combat forces, would have been in keeping with existing doctrine and, in

the opinion of some observers, would have provided a more efficient means

of conducting land combat operations. In the context of events in 1965,

however, adoption of this approach was not so clearly indicated. In

particular, it would have required General Westmoreland to interpose a

new, untested, and inexperienced headquarters between himself and his

newly arrived American combat troops. Of equal concern was the fact that

the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff (JGS) was also the Army of

Vietnam headquarters. Coordination of land combat operations was being

conducted between MACV and the JGS; if operational control of U.S. Army

forces had rested in USARV, the absence of a counterpart headquarters in

the Vietnamese Army would have made co-ordination much more difficult. For

these reasons, the responsibilities of USARV were limited to

administrative and logistical matters.

Before mid-1965, when the first U.S. engineer units arrived, the only

American construction capability in Vietnam resided in a small civilian

force under contract to the Navy. For a number of years the Department of

Defense had followed the practice of assigning to the construction arms of

the Army, Navy, and Air Force areas of

[16]

responsibility around the world where bases were planned, under way, or

already built. The Army Corps of Engineers was given jurisdiction over

military construction contracts in Japan, Okinawa, Taiwan, Korea, the

Mediterranean, and the Near East. Air Force Civil Engineers were assigned

the United Kingdom, and the Navy Bureau of Yards and Docks (which was

later redesignated Naval Facilities Engineering Command) was committed to

Spain, the South Pacific islands, Guantinamo Bay, Antarctica, and

Southeast Asia. As Department of Defense contract construction agent, the

Naval Facilities Engineering Command (NAVFAC) had an Officer in Charge of

Construction (OICC) for Southeast Asia headquartered in Bangkok, Thailand,

with a branch office in Saigon. In July 1965 the Navy divided the area by

creating the position Officer in Charge of Construction, Republic of

Vietnam.

As the military buildup gained momentum, engineer and construction

forces received higher priorities for mobilization and deployment. With

the arrival of contingents of Army engineers, Navy Seabees, Marine Corps

engineers, Air Force Prime BEEF and Red Horse units, and civilian

contractors, U.S. construction strength in Vietnam mounted rapidly.

Because the buildup was so rapid, construction had to be accomplished on a

crash basis, but before that could be done there were numerous logistical

obstacles to overcome. Changing requirements for facilities from which to

conduct or support combat operations and deployments interfered with the

establishment of construction priorities, which in turn depended upon the

availability of labor, equipment, materials, and sites, for which there

was intense competition among the services.

During a visit to Vietnam in July 1965, the Deputy Assistant Secretary

of Defense for Properties and Installations discussed the situation with

the Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics (J-4), MACV, and the commander

of Military Assistance Command. He strongly urged that "there be one

focal point in MACV for direction of construction matters, a central

office with which the Department of Defense, CINCPAC, and other service

agencies can coordinate"; and he recommended a construction czar

other than the MACV J-4.

General Westmoreland had assigned staff supervision of base development

to his Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics. Up to the time of the

buildup, the J-4 had been concerned primarily with the Military Assistance

Program (MAP). Among other duties the J-4 also chaired the U.S.

Construction Staff Committee which consisted of representatives pf

agencies involved in civil and military construction. Within the J-4

office was a Base Development Branch of four officers headed by a Navy

commander and overly. occupied for the most part with routine staff

matters. About twenty-five Engi-

[17]

neer officers were also in the Engineer Branch of the Directorate of the

Army MAP Logistics-a separate staff agency and remnant of the old MAAG.

Headed by Colonel Kenneth W. Kennedy, Corps of Engineers, this branch had

the mission of advising the Vietnamese Armed Forces Chief of Engineers. On

7 April 1965, J-4 merged the Engineer Branch, Directorate of Army MAP

Logistics, with its small Base Development Branch to form the Engineer

Division, J-4, under Colonel Kennedy; but, as the scope of engineer

activities (especially base development) expanded, the post of the

Engineer was upgraded to Deputy J-4 for Engineering in November 1965.

During this same month Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara visited

General Westmoreland's headquarters in Saigon, where he was advised that

the then-envisaged construction program would cost about $1 billion within

a two-year period. Upon his return to Washington, Secretary McNamara

directed the establishment of a construction base for Vietnam. On I 1

February 1966 the position of Director of Construction (MACDC) was

established. As a special staff officer, he would report directly to

General Westmoreland independently of J-4 channels. Brigadier General

Carroll H. Dunn, who had been selected for promotion to major general, was

the first director and served in this post until 1966 when he was

succeeded by his deputy, Brigadier General Daniel A. Raymond. General

Dunn's initial staff consisted of 135 people, half Army, one-quarter Navy,

and one-quarter Air Force. The mission assigned to General Dunn was to

"direct, manage, and supervise the combined and coordinated

construction program to meet MACV requirements and coordinate all

Department of Defense construction efforts and resources assigned to MACV

or in the Republic of Vietnam."

The ultimate mission of the MACV Director of Construction was to provide

military engineering advice and assistance to the Commander, U.S. Military

Assistance Command, Vietnam. In executing this mission the Construction

Directorate supervised the construction program; co-ordinated all

Department of Defense construction efforts and resources assigned to

Military Assistance Command or other agencies in Vietnam; established

joint service policy; and monitored all military construction programs.

The Construction Directorate also supervised the execution of interservice

facility management matters and obtained and allocated real estate for use

by U.S. and Free World Military Assistance Forces. The Construction

Directorate was later given the responsibility for advising and assisting

the Ministry of Public Works, Communications, and Transportation relative

to the government of Vietnam's highway

[18]

and road system. The directorate also assisted the component services,

the Agency for International Development, and the Vietnamese National

Railway System in the development of waterways and railways.

The establishment of the Director of Construction clarified several

matters: the Commander, Military Assistance Command, would exercise direct

control of the construction effort in Vietnam, including direction of the

Navy's Officer in Charge of Construction in areas of project assignments,

priorities of effort, and standards of construction. He would control the

use and allocation of all construction resources in Vietnam. What up to

now had been several programs of separate agencies responsible to

different bosses both in and out of Vietnam became a unified program under

centralized control and direction.

Throughout 1965 there had been an increased commitment of U.S. military

personnel. On 8 March 1965, 3,500 marines landed in the I Corps area to

take up defensive positions around the U.S. air base at Da Nang. On 5 May

1965, U.S. Air Force C-130 aircraft began landing at Bien Hoa Air Base,

north of Saigon, with the main body of the 173d. Airborne Brigade,

previously stationed on Okinawa. On 16 June 1965, the Secretary of Defense

announced the deployment of an additional 21,000 U.S. troops to South

Vietnam, which brought the total commitment to 75,000.

On 12 July, the 2d Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, landed at Vung Tau

and immediately moved inland to Bien Hoa. To the north, the 2d Brigade's

remaining battalion came ashore at Cam Ranh Bay and relieved the 1st

Logistical Command forces of the bulk of the peninsula security mission. A

little over two weeks later, the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division,

landed at Cam Ranh Bay and relieved a battalion of the 2d Brigade, 1st

Division, of its security mission. These two brigades were the first U.S.

Army combat forces to be deployed from the United States to South Vietnam.

On 28 July 1965, in a television address to the nation the President

announced: "I have today ordered to Vietnam . . . forces which will

raise our fighting strength from 75,000 to 125,000 men almost immediately.

Additional forces will be needed later and they will be sent as

requested." In the next five months, the strength of U.S. forces rose

not to 125,000 but to nearly 200,000. By Christmas 1965, the 1st Cavalry

Division (Airmobile) and the 1st Infantry Division (-) had arrived in

South Vietnam, where they were joined by the Korean 1st (Capital-Tiger)

Infantry Division. To control the U.S. combat forces in II Corps, Task

Force Alpha, a corps head-

[19]

ELEMENTS of 1st CAVALRY DIVISION (AIRMOBILE) arrive at Qui

Nhon September 1965.

quarters, was deployed in August from Fort Hood, Texas, to Nha Trang.

The troop buildup continued into the new year. On 29 December 1965 the

3d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, began a two-week movement from

Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, to Pleiku. By 8 January 1966 a second corps

headquarters, designated II Field Force, was deployed to manage U.S.

combat forces in the III and IV Corps areas.

The first Army engineer unit to arrive in Vietnam was the 173d Engineer

Company, which landed at Bien Hoa on 5 May 1965 as part of the 173d

Airborne Brigade. This company, like other brigade and divisional engineer

units, worked to establish base camps and provide combat support to the

larger organization of which it was a part.

On 9 June 1965 Headquarters, 35th Engineer Group, together with the

864th Engineer Battalion and D Comp4ny, 84th Engineers, had debarked on

the Cam Ranh Peninsula. These were the first major units to arrive at Cam

Ranh Bay. On 16 July the 159th Engineer Group (Construction) at Fort

Bragg, North Carolina,

[20]

received orders to activate Headquarters, 18th Engineer Brigade, from

its resources. On 30 July the newly formed brigade received movement

orders, and one month later it departed for South Vietnam and assignment

to U.S. Army, Vietnam. This brigade was commanded by Brigadier General

Robert R. Ploger. The brigade's advance party arrived in Vietnam on 3

September and immediately scrambled to find space in the Saigon area for

its headquarters and to establish a communications net with its

subordinate units. On 16 September the headquarters (less the main body,

which did not arrive until 21 September) became operational and assumed

command of all nondivisional Army engineer units from the 1st Logistical

Command. In northern II Corps, meanwhile, the engineer situation was

significantly changed by the arrival at Qui Nhon of Headquarters, 937th

Engineer Group (Combat), and the 70th Engineer Battalion (Combat) on 23

August. These units came to South-east Asia as time-tested organizations,

since both had been in operation before deploying. By 1 October 1965 the

engineer force was composed of two group headquarters, six battalions, and

nine separate companies. One week later USARV assigned the following

missions to the brigade:

a. Provide operational planning and supervision of USARV construction

and related tasks in the Republic of Vietnam and for other missions as may

be directed by this headquarters.

b. Exercise command and operational control of engineer units assigned

to United States Army, Vietnam.

c. Provide for physical security of personnel, equipment, facilities,

and construction of all units assigned or attached to your command.

On 1 January 1966 the 20th and 39th Engineer Battalions, along with the

572d Light Equipment Company, landed at Cam Ranh Bay. From 2 January until

mid-May, only two companies were added to the strength of the 18th

Brigade. The 20th and 39th Battalions were the last products of the

initial herculean push by the United States Continental Army Command to

deploy a maximum number of engineer units to Southeast Asia. It would be

summer before the steady flow of engineers across the Pacific would

resume.

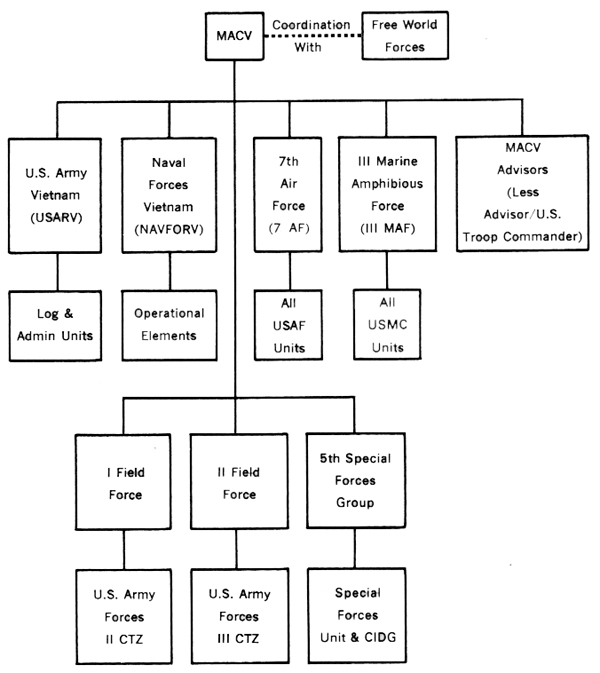

The command situation for base development was by now formally

established. The Director of Construction at the MACV joint staff

headquarters exercised control and guidance for all service construction.

Air Force, Navy, and Army construction efforts would

[21]

be co-ordinated through this office. To ensure effective operation, the

Construction Directorate was organized along functional lines. The

directorate originally consisted of five main divisions: Plans and

Operations, Engineering and Base Development, Construction Management,

Real Estate, and Program Management. On 1 January 1968 a major revision of

the organization occurred with the creation of the Lines of Communications

(LOC) Division. (Chart 3) The LOC Division assumed the responsibility for

managing a 4,100kilometer road restoration program and for advising the

Vietnamese Director General of Highways. Before this reorganization, LOC

responsibility had been delegated to the Construction Management

[22]

Division, which was dissolved. Its functions were assumed by the Base

Development Division.

The Base Development Division served as the focal point for base

development planning, for monitoring the component service base

construction projects, and for interservice facility management matters.

Engineer staff activities pertaining to military operation, determination

of engineer requirements and plans for employment of engineer forces, and

technical supervision of engineer activities were the responsibility of

the Plans and Operation Division.

The Lines of Communications Division, once established, directed,

supervised, and managed the development and restoration of designated

roads to support military operations, pacification programs, and national

economic growth. The division co-ordinated the planning and execution of

LOC programs for the component services, the Agency for International

Development, and the Vietnamese government. Assistance and advisory

support were also provided to the Ministry of Public Works,

Communications, and Transportation; to the Directorate General of

Highways; and to the five regional engineers and the province engineers.

The Lines of Communications Division also assisted all interested agencies

in the development of waterways and railways. The Program Management

Branch, meanwhile, was responsible for funding matters including fund

status, piaster impact, and statistical analysis of the Vietnamese

military construction program, while the Real Estate Division served as

the MACV agent in obtaining and allocating real estate for U.S. use.

The commander of Army units in Vietnam remained the Commanding General,

U.S. Army, Vietnam. As senior Army component commander, he was responsible

for base development at ports, beaches, depots, and major installations in

II, III, and IV Corps Tactical Zones, except for those bases specifically

assigned to other services through the office of the MACV Director of

Construction. Since the Commanding General, U.S. Army, Vietnam, was also

the Commander, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, this apparent

division of command may be seen as a simple differentiation of staff

functions made necessary by the diversity of responsibilities inherent in

the planning staff, which was MACV, and the execution staff, which was

USARV.

Initially the Army engineer construction effort was the responsibility

of the Engineer Section of the 1st Logistical Command. In September 1965

the headquarters of the 18th Engineer Brigade arrived and assumed

responsibility of engineer staff planning from the 1st Logistical Command;

the Commanding General, 18th Engineer Brigade, acted as both the Engineer

Troop Commander and

[23]

the Army Engineer until December 1966 when the U.S. Army Engineer

Command was formed. The 18th Engineer Brigade was then delegated the

responsibility for engineer support in I and II Corps Tactical Zones. The

Engineer Command took over responsibility for over-all supervision of the

Army construction program and direct supervision of two engineer groups

operating in II and IV Corps Tactical Zones. When the 20th Engineer

Brigade arrived in Vietnam and was delegated the responsibility of

engineer support in III and IV Corps Tactical Zones, the Engineer Command

functioned as the over-all planning staff for Army construction

subordinate to the Engineer, USARV. In March 1968 the Engineer Command was

reorganized with the U.S. Army Engineer Construction Agency, Vietnam (USAECAV),

and was charged with responsibility for managing and administering real

estate, property maintenance, and execution of the Military Construction,

Army (MCA), construction programs. At the same time the Office of the

Engineer, USARV, served as the component staff engineer.

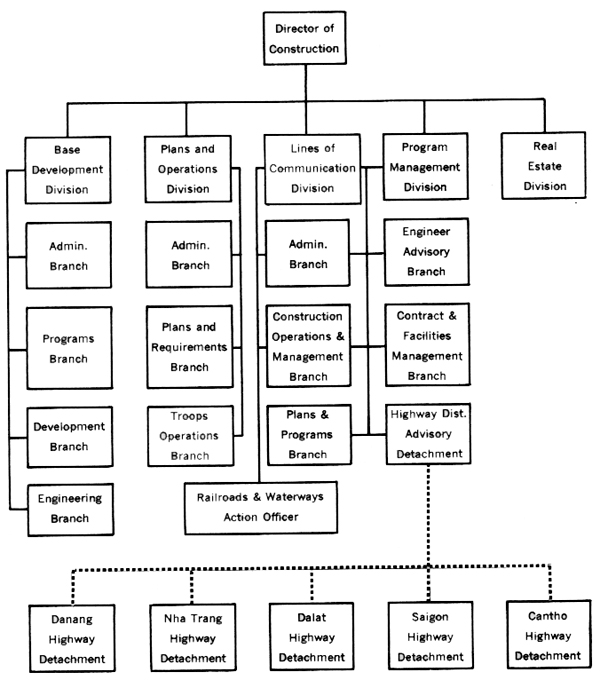

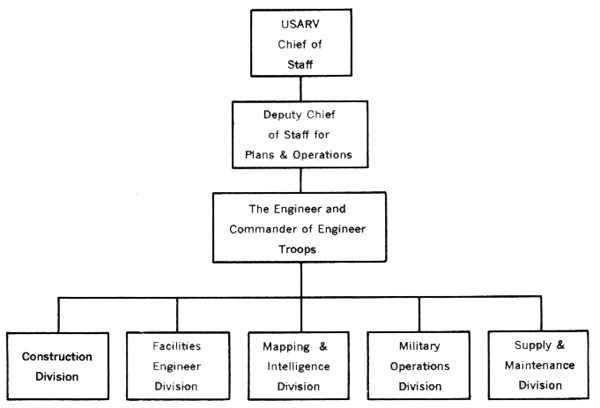

The Engineer's staff at USARV headquarters consisted of five main

divisions: Construction, Facilities Engineering, Mapping and Intelligence,

Military Operations, and Supply and Maintenance. (Chart 4) Although the

organizational structure of the Construction Agency provided for

operational independence, policies and proce-

[24]

dures were prescribed by U.S. Army in Vietnam. The Construction Agency

at Army headquarters was composed of three main divisions: Engineering,

Real Estate, and Real Property Management. The USAECAV organization also

utilized the area concept and had district offices in four major

geographical locations.

Like the Construction Agency, the engineer brigades were subordinate to

the U.S. Army in Vietnam and their organization and mission evolved in an

area concept. The brigades each operated in two tactical zones. Since the

brigades divided their areas into group and battalion areas of operations,

the battalions were responsible for all engineer support within assigned

areas of operation.

Naval construction planning at the beginning of the buildup was

delegated to the III Marine Amphibious Force. In October 1965, III Marine

Amphibious Force was provided a small support activity which was an

extension of Services Forces, Pacific, and the Director of the Pacific

Division of Bureau of Yards and Docks. This activity assumed the

responsibility for facility planning until April 1966 when the Commander,

Naval Forces, Vietnam (COMNAVFORV), assumed the duties of co-ordinator and

planner for base, port, beach, depot, air base, road, and installation

construction for all Navy, Marine, and allied forces operating in I Corps

and for other distinct naval operations in II, III, and IV Corps areas.

The Commander, Naval Forces, Vietnam, as the Navy component commander,

was placed under operational control of the Commander, Military Assistance

Command, Vietnam, but remained under the operational command of the

Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, the operating naval force of the

Commander in Chief, Pacific.

The Department of Defense contract construction agent in Vietnam, the

Navy's Officer in Charge of Construction, had been providing construction

resources. This office and its organization had been modified frequently

since 1962 when the Navy negotiated a $16.5 million cost-plus-a-fixed-fee

contract with a joint contractor, Raymond International and

Morrison-Knudsen (RMK), for construction of airfields and port facilities

in Vietnam to support the country's armed forces. The buildup of American

forces increased the scope of contract construction. In August 1965 RMK

brought two additional contractors-Brown & Root and J. A. Jones--into

the partnership (henceforth referred to as RMK-BRJ) to bolster personnel

strength and management capability. Lyman D. Wilbur, vice president of

Morrison-Knudsen, was in charge of work from May 1965 until February 1966,

when he was succeeded by Bert Perkins, also a vice president of the same

corporation.

The Navy's OICC in supervising the RMK-BRJ contract assigned a Naval

Civil Engineering Corps officer as resident officer

[25]

in charge at each major construction site. The OICC since 1965 had been

a Navy flag officer of the Civil Engineer Corps.

Unlike the other services, the Air Force was able to avoid many

construction planning difficulties. The 7th Air Force Civil Engineer

Directorate possessed the planning force required for its construction

program in Vietnam before the 1965 buildup, and the 7th Air Force was

responsible only for base development at air bases and at other

installations where the Air Force was designated as having a primary

mission.

The Army's responsibility for facilities engineering support before 1965

was limited to six MACV advisory sites located outside Saigon. The Navy's

Headquarters Support Activity, Saigon, took care of all military property

within the city. But because of a lack of trained military personnel and

experience in contracting for facilities engineering in Korea, the Army

decided to contract for this support at the MACV advisory sites. Seven

firms submitted bids, and negotiations were undertaken with four of them.

On 1 May 1968, Pacific Architects and Engineers (PA&E) received a

cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract.

This contract, except for a change in the type of fee, was the kind

awarded as the buildup continued. The contractor was to provide all

facilities engineering support for the Army in Vietnam and was to

establish an organization essentially the same as provided in Army

regulations for standard facilities engineering units. The contractor was

to furnish the labor, organization, and management; the government was to

supply equipment, repair parts, tools, and material as well as quarters

and messing facilities. The flexibility of this contract proved invaluable

in the years ahead.

While considerable attention is given in this text to the deployment of

Army engineer units, it should be recognized that these units actually

constituted less than half of the total American construction force in

Vietnam. By mid-1968, thirty-five engineer battalions, forty-two separate

companies, and numerous teams and detachments hart been deployed. At its

peak, Army engineer strength in Vietnam approximated 40,000 officers and

men, including members of combat engineer units of the seven Army

divisions and six separate brigades and regiments.

The following summary sets forth what might be termed the construction

force in Vietnam. Essentially it lists the principal agencies involved in

construction in South Vietnam, and therefore the agencies whose

construction activities were co-ordinated, integrated, and directed to

varying degrees by the MACV Director of Construction.

[26]

U.S. Army

1. Army Engineer Command (Provisional). Consisted of 2 brigades, 6

groups, 21 battalions, and various small specialized engineer units.

2. Pacific Architects and Engineers. Under contract for repairs and

utilities support of the Army (21,418 personnel).

3. DeLong Corporation. Fabricated and installed patented mobile piers.

4. Vinnell Corporation. Constructed, operated, and maintained electrical

systems including T-2 tankers used as power sources.

U.S. Air Force

1. Walter Kidde Constructors. Employed on a turnkey basis to design and

construct Tuy Hoa Air Base.

2. Red Horse Squadrons. Five light construction squadrons structured for

augmentation by local labor.

3. Base Emergency Engineering Forces (BEEF) Teams. Small detachments

which contained a high level of skills and capability of constructing

small quantities of critical facilities.

4. Base Civil Engineering Forces. Equipped to handle repairs and

utilities at established bases.

U.S. Naval Forces

1. One construction brigade, composed of the 80th Naval Construction

Regiment with nine Seabee battalions.

2. Three engineer construction battalions of the Fleet Marine Force,

USMC.

3. Naval Support Activity, Public Works Forces.

4. Philco. Under contract to provide a labor force.

5. Naval Facilities Engineering Command

a. Office in Charge of Construction (OICC), RVN. OICC supervised and

administered the contract for:

b. RMK-BRJ. This joint venture of four American contractors accomplished

the largest portion of construction projects.

Other U.S. agencies in the organization for construction were those of

the embassy's Office of Civil Operations and the MACV Revolutionary

Development Support Directorate.

Until early 1967, there was a tendency to view the reconstruction phase

of pacification as a Vietnamese effort, supported by U.S. civil agencies,

while the U.S. military command concentrated on building Vietnamese combat

capabilities. Integration and co-ordination were lacking among the several

U.S. civil agencies involved. The U.S.

[27]

Agency for International Development (USAID), the Joint United States

Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO), and the Office of the Special Assistant to

the Ambassador (OSA), and the military agencies sometimes worked at

cross-purposes. To correct this defect the Civil Operations and Rural

Development Support (CORDS) structure was formed under MACV to provide

single manager control of U.S. military and civilian efforts in support of

Vietnamese pacification programs. CORDS did not include all of the

advisory efforts of OSA and JUSPAO. These organizations continued to

supply some construction material to the Vietnamese for self-help, while

military units often performed the actual reconstruction.

[28[

page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents