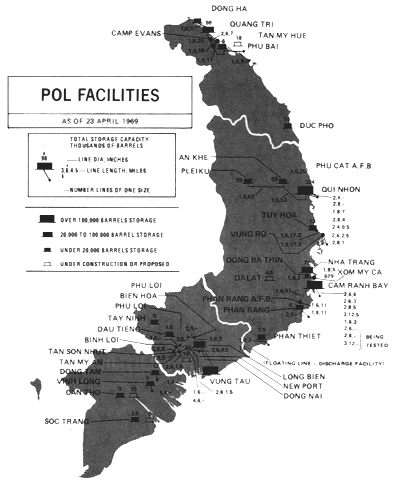

| Location | Storage Capacity Total Thousands Of Barrels |

Number And Capacity Of Tanks In Place Thousands Of Barrels |

In-Line Pump

Capacity Barrels/Day |

Incoming Pipelines Number, DIA, (Inches), Length (Miles) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Place |

Under Cons- tructions |

Pro- posed |

||||

| Dong Ha | 3.0 | 5-10 | 18,000 | 1,6,5 | ||

| Quang Tri | 59.0 | 3-3 | 18,000 | 1,6,20 | ||

| Hue | 36,000 | 2,6,7 | ||||

| Phu Bai | 6.0 | 18.0 | 2-3 | 18,000 | 1,6,11 | |

| Camp Evans | 18,000 | 1,6,18 | ||||

| Duc Pho | 16.0 | 5-3 1-1 |

||||

| Phu Cat (AFB) | 18,000 | 1,6,20 | ||||

| Pleiku | 59.0 | 3-3 | 18,000 | 1,6,53 | ||

| An Khe | 69.0 | 5-10 5-3 |

18,000 | 2,4,0.5 1,8,7 3,8,4 |

||

| Qui Nhon | 324.0 | 3-50 14-10 2-5 8-3 |

145,740 | 1,6,17.2 1,8,17.2 |

||

| Tuy Hoa | 13.0 | 4-3 2-0.5 |

43,000 | |||

| Nha Trang | 72.0 | 6-10 4-2 |

||||

| Dalat | 4.5 | |||||

| Cam Ranh Bay | 172 204 200 3 |

4-50 34-10 13-3 |

38,000 38,000 65,000 50,000 19,000 |

2,6,6 2,6,3 2,8,5 3,12,5 1,6,3 |

||

| Phan Rang | 6.0 | 2-3 | 43,000 | 1,6,11 1,8,11 |

||

| Tay Ninh | 9.0 | 3-3 | ||||

| Dau Tieng | 1.5 | 3-0.5 | 18,000 | 1,6,20 | ||

| Phan Thiet | 7.5 | 8-10 2-3 |

8,520 |

1,4,2 | ||

| Long Bien | 86.0 | 57,000 24,000 |

3,6,4.5 1,8,49 |

|||

| Long Bien (Power Plant) (Vinnell) | 12.0 | 8,000 | 1,4,2 | |||

| Phu Loi | 9.0 | |||||

| New Port | 10.0 | 38,000 | 2,6,1.5 | |||

| Vung Tau | 250.0 | 3-50 10-10 |

||||

| Dong Tam | 12.0 | 4-3 2-0.5 |

||||

| Vinh Long | 9.0 | 2-3 3-1 |

||||

| Can Tho Binh Thuy | 3.0 | 15.0 | 3-1 | |||

| Soc Trang | 2.5 | 6.0 | 2-1 1-0.5 |

|||