- Chapter VIII:

The Road Programs

The extensive highway system in the Republic of Vietnam was

constructed mainly during the past five decades. Before 1954,

approximately 20,000 kilometers of road existed, of which about

6,000 kilometers were national or interprovincial and 14,000

kilometers were rural or secondary roads. By the time of the

cease-fire in 1954, most of the country's highway network had been

destroyed, and long segments of the highway system had become

impassable to motorized traffic. The highways that remained were

generally inadequate for military usage because of either faulty

design or poor surfacing. Most bridges were destroyed. The national

highway system, particularly National Route 1, sustained the most

damage. Six hundred and fifty kilometers of Route 1 from Phan Thiet

to Hue were largely impassable. To reopen the road approximately 240

bridges with a total length of 11,295 meters had to be

reconstructed, endless culverts installed, and thousands of cubic

meters of fill had to be replaced where erosion had taken its toll.

In the government of Vietnam, the Director General of Highways is

responsible for administration of the design, construction, and

maintenance of the national and interprovincial routes, while the

provincial roads and city streets are administered by local

governments. However, in 1971, the director was assigned the

maintenance responsibility for rural roads, while reconstruction of

rural roads remained a provincial function.

Efforts of the Director General to repair and maintain the highway

system were halted by the enemy. Even if the government had been

successful, it is doubtful that a satisfactory level of highway

maintenance could have been attained; the increased weight and

volume of heavy military vehicles would have quickly negated the

Vietnamese effort. In 1966 Army engineer troops began to reopen

highways and rebuild bridges to support tactical and logistic

traffic. The engineer force was probably adequate, but its effort

was limited by other priority missions.

In early 1967 the idea of a formal highway restoration program,

initially utilizing troops and later civilian contractors, was

conceived as the result of a combined effort on the part of the

government of

[99]

Vietnam, the United States Agency for International Development,

and the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The combined Central

Highways and Waterways Coordination Committee (CENCOM) was formed to

establish priorities of restoration, to develop standards of

construction, and to fund actual construction. CENCOM was comprised

of representatives from the Vietnamese General Staff, the Agency for

International Development, the Directorate of Highways, the Military

Assistance Command, and the Marine Director of Public Works. The

chairman was the Chief of Staff of the Vietnamese joint General

Staff. The program envisioned the eventual restoration and upgrading

of approximately 4,075 kilometers of highway, which the committee

considered essential in support of military operations, to stimulate

economic development, and to accelerate the pacification program by

opening up rural areas. The information of the combined committee

permitted the development of a national restoration program in

consonance with military campaign plans.

In April 1968 the Agency for International Development published a

formal announcement of the transfer of the highway mission, with the

exception of secondary road projects, to the MACV Director of

Construction. Included in the transfer were the Nui Sap Quarry

operation, the National Highway Training School, the Suoi Lo

Maintenance and Repair Parts Activity, and nineteen USAID engineers.

The Director of Construction then organized a Lines of

Communications Division to advise the Vietnamese Director General of

Highways and to co-ordinate the massive contractor and troop effort

involved in the highway restoration program. The Lines of

Communications Division organized five district highway advisory

detachments to correspond with the highway directorate's field

organization. The detachments' primary mission was to advise the

Vietnamese District Engineer and his staff.

The advisory mission was established as a three-phase operation.

Phase I was to effect transition of the ongoing organization from

USAID control to MACV. Phase II was to substantially increase the

advisory effort available to the Vietnamese District Engineer. Phase

III would be the transferral of the responsibility back to the

Agency for International Development in 1971. The objective of the

highway restoration program was to upgrade designated highways over

a four-year period to adopted standards and in accordance with

established priorities.

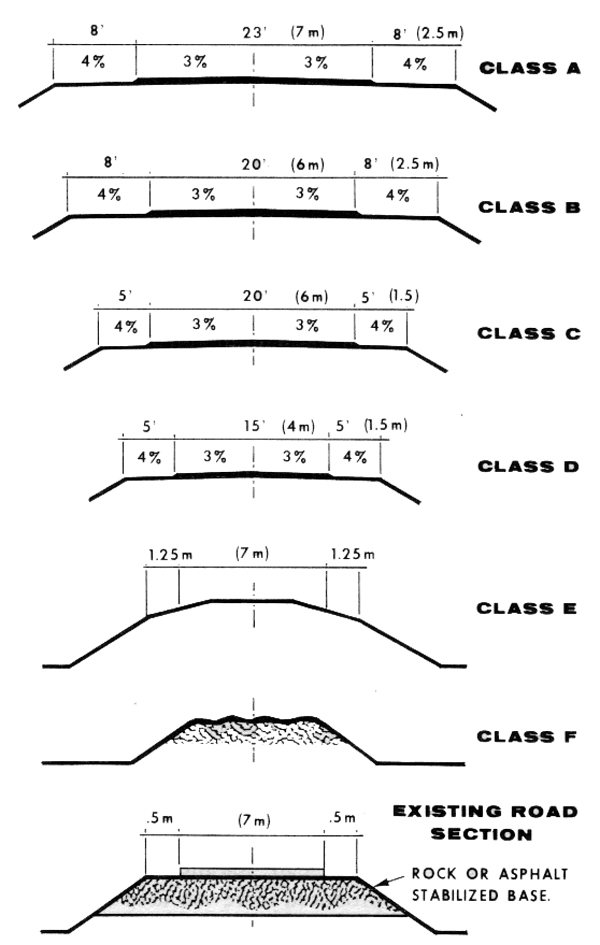

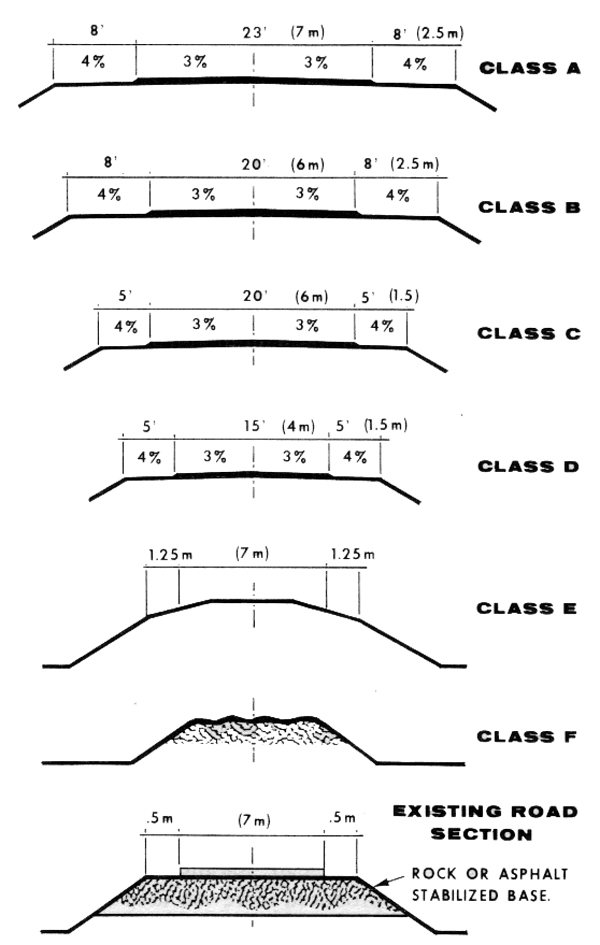

Construction standards followed the criteria established by the

American Association of State Highway officials. The standards which

were identified by letters A through F had a design life for a Class

A road of twenty years down to ten years for Classes C or D.

[100]

Pavement structure design procedures were standardized using

estimated traffic factors to approximate a twenty-year design life.

Each class of highway had specific geometrics. Cross sections of

each class are shown in Chart 7. The Class F highway was an

innovation introduced by MACV's Director of Construction. This class

made maximum use of the existing French-constructed highway and

based its

[101]

alignment on the existing embankment. Essentially this class

highway called for laying a rock or asphalt stabilized base over the

existing highway and a widening of the traveled way, or actual road

less shoulders, to seven meters. The entire surface would then be

paved with an asphaltic concrete. Design life would not be

specified. The Class F highway would be constructed extensively in

the delta, thus minimizing embankment and realignment requirements

and speeding up the highway restoration program there.

Sixteen engineer battalions undertook the U.S. Army's portion of

the highway restoration program. The work force was composed largely

of construction battalions; however, an average of three combat

battalions augmented with equipment companies were engaged in the

program at any given time. Although restoration of the roads was

their main task, construction units frequently received orders to

support combat units or were given other priority missions. Unit

commanders tried to construct all highways in accordance with

established priorities, but on many occasions combat engineers

called on them for help and missions were shifted.

To carry out the program, units had to establish base camps along

the routes to be upgraded. This requirement made it necessary to

devote a part of the available manpower to base camp and industrial

site construction. Quarries and asphalt plants had to be

established, construction routes and security had to be maintained,

and that drew off more manpower.

To maintain construction schedules, a vast amount of material had

to be procured and transported to the construction sites. Initially

the demand on procurement and transport was light, since

construction was centered near large U.S. logistics bases. But as

demands increased and construction forces moved farther away from

the larger bases, a tremendous burden was placed on the entire

supply system. To reduce the number of times material was handled,

the Engineers attempted to ship directly from supply points to

users. Stocks of cement, asphalt, and culvert material began to

dwindle rapidly. As material shortages threatened delay,

logisticians pulled out all the stops and attempted to meet demands

any way possible. Critically needed items were improvised or

borrowed from other services.

In 1966 there was an acute shortage of rock in III and IV Corps

areas. At that time there were only two sources for crushed rock-a

contractor-operated quarry near Saigon University and the quarries

thirty miles away at Vung Tau. Because Vung Tau had no connecting

roads, the rock produced there was used there with only small

quantities being shipped by barge to the Long Binh area. The need

for rock was so urgent that a special "buy" of rock was

[102]

made from a Korean contractor who shipped rock all the way from

quarries in Korea.

When the first shipment of rock arrived in Saigon, headaches

really began. Customs, harbor, and lighterage problems combined to

produce lengthy delays and creeping costs. A scheme was finally

devised whereby the rock was loaded into "smaller craft"

at Saigon for the trip to Thu Duc, to be unloaded there by heavy

equipment into trucks for the short haul to Long Binh. A crane with

a two cubic-yard clamshell, or heavy steel scoop, was positioned at

Thu Duc to unload the rock. There was considerable consternation as

the small craft loaded with rock began arriving at Thu Duc. The

small craft were hundreds of sampans-the largest nearing twenty feet

stem to stern and loaded to within six inches of freeboard. The

weight and size of the clamshell would have sunk them easily.

Reluctantly, conveyors and hand labor were used to bring the rocks

ashore. Stockpiles from which the clamshell could operate slowly

grew on the beach. Since this method of supplying rock was rather

nightmarish, the first shipload was also the last. The contract was

terminated.

The entire highway restoration program was originally scheduled

for completion by 1974. But because of the tactical and economic

importance of the program, General Westmoreland directed the Army to

have the majority of the roadwork finished by 1971. The principal

obstacle was the shortage of construction equipment. The solution

was for the Army to purchase high-production commercial equipment to

augment the standard items used by engineer units. In mid-1968 the

U.S. Army in Vietnam, in conjunction with the Army Engineer

Construction Agency and the 18th and 20th Engineer Brigades, studied

the equipment problem from all angles. The study resulted in a

recommended list of commercial construction equipment that would be

needed to meet the target completion date of December 1971. In

determining the type of equipment required, specialists developed

seven general categories and assigned each category a rating

reflecting its importance to the success of the project.

In mid-1968 the rock production capabilities of both engineer

brigades received a thorough analysis including actual and

anticipated assets. These capabilities were then compared with all

other rock requirements. From this study it became apparent that

additional rock-crushers would be required to complete the road

program by the specified time. Eight 250-tons-per-hour (TPH),

readily portable, crushing plants were selected and included in the

equipment purchase order. High-volume crushers were considered the

key to the success of the project. As these crushers reached

Vietnam,

[103]

ROCK-CRUSHING OPERATION, essential to virtually all phases of

construction.

they replaced the lower capacity 75-TPH plants. The, newer 250TPH

plant was as portable as the 75-TPH plant but easier to operate and

maintain, produced at least three times as much rock, and required

fewer operators. Although the larger plant was designed with

emphasis on high-volume base rock production, the all-electric plant

had the capability of producing well-graded aggregates. The rapid

rate of road improvement in 1969 was possible only because six

225-TPH rock-crushers had arrived from CONUS depot stocks. These

crushers played a major part in the program until the Military

Construction 250-TPH crushers arrived. These crushers required only

one operator whereas the 75-TPH needed three. As the new crushers

arrived in the theater, many of the 75-TPH units which were not

economically repairable were turned in. The operators previously

required for the 75-TPH crushers were then available for other

equipment.

The scarcity of rock-drilling equipment also hindered progress.

Engineer units had far too few drills capable of keeping up with the

increased demand for rock. Reinforcements in drilling equipment were

necessary to feed the eight 250-TPH crushers and the six 225-TPH

crushers. To meet the demand, thirty-six track drills and

600-cubic-foot-per-minute air compressors were added to the

equipment purchase list.

Requirements for hauling rock within the quarries were met by

[104]

ROCK DRILL operating on quarry face.

purchasing one hundred 15-cubic-yard Euclid dump trucks in 1967.

But to load the Euclids, feed the crushers, and stockpile aggregate,

twenty-nine 6-cubic-yard tractor shovels were needed. Far simpler to

operate and faster and easier to maintain, each of these units could

replace two 40-ton shovels. Furthermore, an experienced heavy equipment

operator could become reasonably proficient on the

machine in a matter of several days, whereas many months were

required for him to become equally proficient on a crane shovel.

To augment existing trucks, 226 twelve-cubic-yard, hydraulically

operated, dump trucks were selected for purchase. Under comparable

conditions, these trucks have twice the capacity of the military

5-ton dump truck and were requested specifically to haul large

quantities of base rock and asphaltic concrete on medium to long

hauls over improved roads.

The earth compaction equipment used by engineer units was not in

scale with the projected construction rate of 774 kilometers a year.

Compactors capable of doing more work in less time were urgently

needed to augment the equipment in the construction battalions. The

purchase of sixty commercial heavy-duty compactors certainly

increased the capabilities of our engineer units.

The concept of the road program also included the rapid placing of

pavement. In addition to strengthening and protecting the road-bed, paving would make mine emplacement more difficult for the

enemy. To supplement existing military equipment and to speed up the

over-all paving rate, six asphalt pavers and fourteen asphalt

[105]

SHEEPSFOOT ROLLER compacting a runway extension at Bu Dop

airstrip.

distributors were ordered. To redirect and channel the runoff

which results from the torrential monsoon rains, seven asphalt curb

extruders were included in the order. These were put to use

primarily in the Central Highlands, but were also used to

manufacture curb and gutter systems for villages and towns in other

areas.

To keep culvert installation ahead of over-all road building, and

at the same time assure quality construction, hand compactors were

requested to speed up culvert backfilling and compaction operations.

Twelve backhoes were also added to the equipment list to aid in the

placement of culverts and excavation in restricted areas. Thousands

of man-hours required for hand excavation of culverts and trenches

and many hours of equipment time on crane mounted shovels or

clamshells were saved by the backhoes.

The addition of commercial cement mixers had been requested to

accelerate the construction of concrete abutments, deck slabs, and

approach slabs for bridges along the roads. This equipment was

designed to minimize the labor force needed for concrete work. There

were approximately 675 new bridges with an average span length of

forty feet to be constructed to satisfy immediate tactical

requirements. The type of bridge planned required approximately

[106]

165 cubic yards of concrete per bridge. The small 16S cement

mixers were being replaced by central batch plants and transit

mixers which greatly reduced the stockpiling requirements and the

man-hours needed to produce the concrete required for each bridge.

By carrying a dry mix in the transit mixers, more than one bridge

could be worked on at one time. In the long run, both production and

maintenance man-hours were significantly reduced.

In the Mekong Delta all rock and other conventional material for

road and other construction had to be imported. Crushed rock

produced at quarries in the upper regions of the country moved by

barge into the delta for the road construction program. Barge

offloading facilities were constructed, and an Army Engineer

Hydrographic Survey team charted many of the canals of the delta to

develop water transportation routes. To reduce cost the use of a

lime-cement stabilized base or sub-base in lieu of a conventional

base was planned for all delta road construction. Elsewhere in

Vietnam the use of stabilization techniques was planned to reduce

requirements in areas where little rock was available. The

procurement of sophisticated stabilization equipment capable of

mixing stabilizing agents, such as cement, calcium chloride, and

emulsified asphalt with aggregate, was considered vital for project

completion. A total of nine 300-TPH stabilization plants and three

self-propelled stabilization machines were requested. These plants

represented a revolutionary change in theater construction methods.

While the addition of commercial construction equipment increased

production, the redeployment of engineer battalions, which began in

September 1970, reduced U.S. troop strengths below that needed to

meet the December 1971 completion date. To partially offset the

troops losses, some engineer battalions were augmented with local

labor. Initially the local laborers were used for unskilled or

semiskilled duties. However, by the end of 1970, the Vung Tau quarry

was predominantly staffed with Vietnamese labor; several dump truck

platoons employed Vietnamese drivers; and carpenter prefab and

bridge deck prefab yards were almost entirely Vietnamese operated.

In early 1971 an all-Vietnamese asphalt concrete paving train was

being organized.

The secondary road program, as it neared completion, was a

significant incentive to the development of Vietnam, particularly in

the areas of agriculture, economy, and mobility. This diversified

highly. productive program permitted U.S. and Vietnamese engineers

to work side by side and eventually developed a proficiency in

Vietnamese units for both construction and maintenance of the road

system.

The stimulus to agriculture was particularly pronounced in

[107]

previously evacuated areas. Construction of a secondary road

presupposed a relatively secure area, which was ripe for

resettlement. While the road was not necessary for the movement of

relocated people and their few personal belongings, it was crucial

to the establishment of a market for their crops. A difference of a

few miles and a few hundred feet in elevation often resulted in

differing climate and soil conditions which dictate the primary

production of tea and manioc, rather than rice; hence the need for

easily accessible markets in other than the settlers' own village.

The opening or reconstruction of secondary and rural roads was

recognized by General Westmoreland and pacification officials as

critical to the pacification and economic growth of Vietnam. The

tremendous advances in pacification in the delta, for example, were

a direct result of the road building program.

The railway system in Vietnam was originally constructed by the

French between 1902 and 1936. Immediately after the Geneva Agreement

in 1954, the Republic of Vietnam mobilized its financial, technical,

and labor resources under the newly formed semiautonomous railway

agency, the Vietnam Railway System, and began the reconstruction of

its road between Saigon and Dong Ha near the 17th parallel. By

August 1959 the reconstruction of the main line and branch lines was

completed, except for the Loc Ninh branch. The United States

government through the embassy's Operating

SCRAPERS PREPARE A RIGHT OF WAY before crushed rock is dumped.

[108]

Mission assigned a railway adviser to Vietnam in 1957 at the

request of the Vietnamese government.

From 1960 to 1964 the Vietnamese Railway System operated scheduled

freight and passenger trains on the entire line, transporting

approximately half a million tons of cargo and four million

passengers annually. In 1962 the U.S. military assigned security

advisers to the Vietnamese Military Rail Security Forces. During

this period the system continued to upgrade its entire organization

by modernizing shop facilities, mechanizing track maintenance,

changing motive power from steam to diesel-electric, and replacing

rolling stock with modern equipment. The United States assisted with

commodity grants amounting to $12 million and a development loan of

$7.8 million. The Australian government furnished ten modern

passenger cars valued at U.S. $900,000.

In November 1964, typhoons Joan and Iris, the worst to strike

Vietnam in sixty-five years, did considerable damage to the railway

system and, with unabated Viet Cong sabotage, the railway was

severed in many places with operations restricted to five separated

segments.

In 1966 the U.S. government through the Agency for International

Development pledged further support in commodities provided that the

Vietnamese took the initiative to secure and reopen the rail system.

This action was sanctioned by the U.S. military, which acquired and

brought into the country two hundred rail cars and ten switching

locomotives to supplement the fleet of Vietnamese rolling stock for

the handling of military cargo.

This second reconstruction effort began in December 1966 and

progressed in those areas where security was re-established. During

this second reconstruction period the U.S. government assisted with

U.S. $11 million in commodity grants. The system reopened 340

kilometers of main line in areas where security was restored. The

government subsidized the road for this reconstruction in the amount

of Vietnamese $211 million, in addition to the subsidy for

operations or sabotage.

The railway contributed significantly to the war effort, the

pacification program, and the economic growth of South Vietnam. For

instance, a considerable amount of the rock aggregate used in the

construction of the Tuy Hoa and Phu Cat airfields, as well as Route

1 and other highways, was transported by rail. As of early 1971 the

railroad was in operation in three separate areas with approximately

60 percent, or 710 kilometers, of the 1,240 kilometers of main line

and branch line track in use. The longest run, approximately 400

kilometers, from Song Long Song to Phu Cat handled a number of rock

trains daily for highway construction work. Military

[109]

VIETNAMESE ENGINEERS drive piles for a bridge span near Qua

Giang with new American equipment.

cargo from Qui Nhon and Cam Ranh Bay still moves by rail to Phu Cat, Tuy Hoa, Ninh Hoa, Nha Trang, and Phan Rang. The

system also transports approximately 11,000 passengers weekly over this line. Another segment of 103 kilometers from Hue to Da

Nang,

[110]

which was reopened in January 1969, has averaged approximately

2,000 tons of cargo and 1,500 passengers a week. The remaining 80

kilometers from Saigon to Xuan Loc, serving the Thu Duc industrial

area and the Long Binh and Newport military complex play an

important role in transporting civilian and military cargo Operation

of this line has eliminated a large number of truck run; from the

congested streets of Saigon and the Bien Hoa Highway Three

round-trip passenger trains operate daily over this section of the

road, transporting an average of 40,000 commuters a week.

The economics of moving cargo by rail, plus the advantage of

releasing trucks for work in the provinces, made rail traffic

attractive to the Vietnamese Army and U.S. military.

The entire road program, both the rail and vehicular systems; has

undergone a tremendous change as has Vietnam. The bridge

reconstruction portion of the road program involved the building of

approximately five hundred bridges totaling over 30,000 meters,

During mid-1968, Army engineers were constructing highways to MACV

standards at an equivalent rate of 285 kilometers per year. At the

same time, they were building bases and supporting combat

operations-including land clearing, tactical roads, tactical

airfields, landing zones, and fire bases. Road construction has

continually been paced by crushed rock production and rock-hauling

capability. The Army relied on the contractor's crushers for 38

percent of the 180,000 cubic yards of rock required monthly to

maintain a construction rate of 285 kilometers per year in 1968.

Before a $49 million fund cut was imposed by the Department of

Defense, in mid-1970 goals were assigned for the highway restoration

program.

| Vietnamese Army responsibility |

165 km. |

| Contractor responsibility |

988 km. |

| U.S. Army troop responsibility |

2,520 km. |

| U.S. Navy responsibility |

430 km. |

| Total |

4,103 km. |

As of 17 October 1970, the revised highway restoration program was

63 percent complete with 2,297 kilometers of pavement completed out

of a total of 3,660 kilometers. As a result of the fund cuts and

program review, 442 kilometers of the 4,103 kilometers CENCOM

Program were deferred. The Vietnamese engineers accepted

responsibility for improving 353 additional kilometers in the

program. The revised program totals and goals were as follows:

[111]

|

Revised Program |

Pavement Completed |

Percent Completed |

| Vietnamese Army responsibility |

518 km. |

10 km. |

2 |

| Contractor responsibility |

902 km. |

715 km. |

79 |

| U.S. Army troop responsibility |

1,853 km. |

1,195 km. |

64 |

| U.S. Navy responsibility |

387 km. |

387 km. |

100 |

| Total |

3,660 km. |

|

|

As primary and secondary roads were built or improved, displaced

refugees settled along these roads, constructed new homes, and

tilled the land. Commercial traffic traveled back and forth with

decreasing fear as the area became generally pacified. Land clearing

to remove vegetation along roads and in other selected areas, thus

denying the enemy ambush sites and sanctuaries for resupply, also

accomplished what repeated infantry operations could not. And as the

rail service was improved and security provided, the demand

increased. During 1970 cargo transported by rail climbed 15 percent

over 1969 (from 530,000 to 610,000 metric tons). The net

ton-kilometer evaluation increased 100 percent from 1969 to 1970

(from 24 million to 48 million net ton-kilometers). The number of

passengers transported by rail increased 40 percent from 1969 to

1970 (from 1.75 million to 2.4 million). The net results of the

combined program have not yet proved their greatest worth, but are

well along the way. I consider the road development program the

single most effective and important development program undertaken

by American effort in Vietnam.

[112]

page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents