- Chapter VII:

Facilities Engineering

Facilities engineering, as distinct from new construction, refers

to the series of operations carried out after basic structures are

complete. It involves the services necessary to keep any large

physical plant functioning efficiently: maintenance and repair of

buildings, surfaced areas and grounds, service to refrigeration and

air conditioning, minor ancillary construction, fire prevention,

removal of trash and sewage, rodent and insect control, water

purification, custodial services, management of property, engineer

planning, supply of maintenance materials, and maintenance of

equipment used in the upkeep of a base.

For these operations the Army relied heavily on civilian

contractors working under an arrangement in which the contractor

provided labor, organization, and management, while the Army

provided tools, repair parts, supply, mess facilities, and quarters

for the work force.

A number of factors influenced how facilities engineering support

would be provided. Contingency planning for operations in Vietnam

had not, in any of the joint service plans, developed a requirement

for facilities engineering forces. While operations in Vietnam were

substantially different from those assumed in developing contingency

plans, the fact remained that plans were not developed to support

facilities once erected during previous sessions of contingency

planning. The inability to produce the manpower for a military

facilities engineer force severely limited other military engineer

capabilities from the outset. Most of the engineer utilities

detachments intended for facilities engineering were in Reserve

status, and the decision not to mobilize the Reserve meant that

these forces would be unavailable. The strict limitations on

personnel strength in Vietnam and the desire to keep the ratio of

support troops as low as possible forced consideration of a

predominantly civilian work force. However, low ceilings were

imposed on direct hiring, a complex and slow procedure; this left a

civilian contract force as the only feasible alternative.

Consequently, with the buildup the Army called upon Pacific

Architects and Engineers to expand its organization as the pace of

facilities construction in-

[89]

creased. The contractor's response was commendable, although not

without problems. His strength grew from 274 men located at six

adviser sites in 1963 to a peak strength of over 24,000 in 1968 at

more than 120 locations.

The piecemeal nature of the buildup made it almost impossible to

predict future requirements or even the eventual location of

incoming troop units. The system which evolved was to tailor the

contractor's organization to meet the needs of each installation as

it was established and expanded. The PA&E work force was made up

of a combination of U.S. civilians, Vietnamese, and other

nationalities. The force mix was about 5 percent American, 15

percent other country, and 80 percent Vietnamese. The contract with

PA&E grew to approximately $100 million per year, not including

government-furnished supplies amounting to approximately $20

million.

While the Army relied heavily on Pacific Architects and Engineers,

it knew that the contractor could not do all the work. His civilian

workmen could not enter certain areas of the combat zone and would

go off the job when curfews and strikes were ordered. There were,

however, approximately 1,450 engineer troops mobilized and deployed

in Vietnam as utilities detachments and firefighting and water

purification teams. (See Chart 5.) Military power plant

operation and water supply companies ranged in size from four to

forty men. While some of these units operated at the same locations

as the contractor's forces, they were stationed primarily in

outlying areas where for security reasons civilians were barred.

In addition to the PA&E work force and the engineer utility

detachments, there were a number of smaller contracts let for

specific kinds of facilities engineering support. But, except for

contracts with the Navy and Philco-Ford in I Corps and with Vinnell

for electric power generation, these contracts will not be discussed

individually.

In sharp contrast to the Army, the Air Force facilities

engineering forces were predominantly military. During peacetime,

the Air Force had maintained a significant number of military

personnel as facility maintenance engineers in its stateside

installations. This gave the Air Force a good base upon which to

draw when the conflict in Vietnam developed. A base civil engineer

force is an integral part of an Air Force wing, and when wings were

deployed to Vietnam, their base maintenance forces went with them.

These forces were augmented by Red Horse squadrons (heavy

maintenance and repair units numbering about 400 men) and Prime BEEF

teams (small detachments sent for six-month tours to augment the

base civil engineer forces for specific projects). The Air Force

made con-

[90]

siderable use of contracts, but these were usually for special

tasks, such as power generation and refuse collection.

The Navy also experienced a shortage of trained military

personnel, although it was somewhat better off than the Army in this

regard. In I Corps, Seebees were assigned to the Public Works

Department, Naval Support Activity, at Da Nang. The Seabees managed

the work force augmented by hired foreign nationals and by local

nationals provided under a service contract with Philco-Ford. The

work force was made up of about one-third Seabees, one-third foreign

nationals, and one-third Vietnamese. In contrast to the Army's

contract with Pacific Architects and Engineers, the Philco-Ford

contract served primarily to provide skilled local labor. Except at

a few industrial facilities, the contractor was not responsible for

over-all management. In addition to the forces assigned to the

Public Works Department in Da Nang, the Navy activated two

construction battalion maintenance units and sent them to Vietnam.

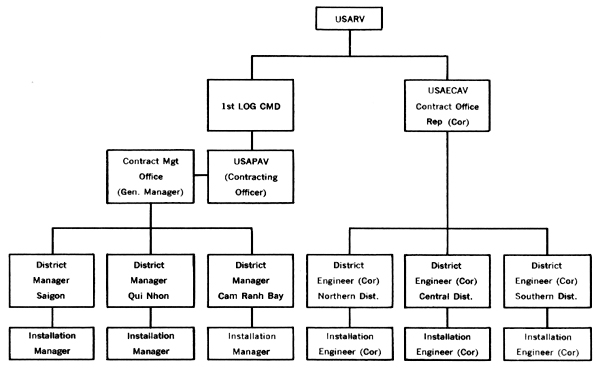

As previously noted, Pacific Architects and Engineers had to

organize and staff its forces along the lines of standard Army

organizations. To control this force, PA&E established a

Contract Management Office in Saigon and three district offices at

Saigon, Qui Nhon, and Cam Rahn Bay from which PA&E forces and

operations at each Army installation were controlled. A highly

effective communications net was operated independently of the

unreliable Vietnamese telephone system and of the military

communications system, which was needed for high-priority

operational traffic.

SEABEES responsible for bridge construction in I Corps

[91]

Administration of contracts and the technical direction and

control of the contractor's activities were, until mid-1968, the

responsibility of the 1st Logistical Command. Within the 1st

Logistical Command, responsibility for contract management was

vested in the U.S. Army Procurement Agency, Vietnam (USAPAV). The

rapid growth of contract work between 1965 and 1967 made it evident

that better control than the procurement agency and the 1st

Logistical Command engineering staffs could provide was needed.

Therefore, the Contract Operations Branch, located at PA&E's

Contract Management Office in Saigon, was established as a part of

the Office of the Engineer, 1st Logistical Command. In addition, the

staff engineers of the Saigon, Qui Nhon, and Cam Ranh Bay Support

Commands, subordinate commands of the 1st Logistical Command, and

the staff engineers of the installations within the support command

areas were delegated appropriate contracting officer's

representative authority. The Contract Operations Branch consisted

of an operations branch, a technical inspection branch, and a

performance and analysis branch. It had the mission of directing the

contractor's activities and analyzing contract operations and

expenditures. This new organization facilitated the identification

and resolution of many problems which resulted in increased

efficiency and responsiveness in the contractor's work.

Increasing construction, real estate, and facilities engineering

costs resulted in a decision to integrate all Army engineer

activities in the U.S. Army Engineer Construction Agency, Vietnam (USAECAV),

in 1968. In July 1968, USAECAV also assumed the facilities

engineering responsibilities formerly assigned to the 1st Logistical

Command except for a direct-hire force supporting the Saigon area

under the direction of the U.S. Army Headquarters Area Command. This

activity was also later transferred to USAECAV in 1969.

Under the Construction Agency organization, district engineer

offices were established at Saigon, Cam Ranh Bay, and Qui Nhon. The

district engineers, in turn, supervised the installation engineers.

This provided a vertical command channel from USAECAV through the

district engineers to the installation engineers independent of

other command relationships. This vertical channel, together with a

substantial increase in the number of military personnel directly

concerned with supervision of the contractor's operations (212 under

the Construction Agency as compared to 73 under the 1st Logistical

Command), substantially improved operations management.

Under the new setup, 1st Logistical Command's procurement agency

retained contracting officer authority, and the contracting

officers, who exercised technical supervision over the contractor,

[92]

reported to two separate headquarters. To overcome the inherent

disadvantages in this arrangement, it was proposed to provide the

Commanding General, USAECAV, with contracting officer authority for

the facilities engineering contract. This, however, was disapproved

by the Department of the Army in order to avoid fragmenting

procurement authority in Vietnam. While this decision did not result

in the optimum organizational relationships from the viewpoint of

managing the facilities engineering effort, relations between the

procurement agency and the construction agency under a memorandum of

understanding were excellent. Through mutual effort, the

difficulties inherent in the organizational relationship were

minimized.

The form of the contract with PA&E underwent several changes.

Originally negotiated as a cost plus a fixed fee in 1963, the

contract remained in effect until 1970. To increase the contractor's

incentive in performance of the contract, the Procurement Agency

assisted by the Construction Agency negotiated a cost-plus-award-fee

contract in 1969. Under this contract the company was evaluated on

its performance, and the fee depended upon this evaluation. The new

agreement appears to have resulted in increased effectiveness and

efficiency.

An effort was made to introduce competition by splitting off the

Qui Nhon area in 1968 and advertising for new bids. Because PA&E

was already working in Vietnam and was familiar with facilities

engineering operations there, the firm had a distinct advantage over

any competitors. Consequently, the new contract also went to Pacific

Architects and Engineers. The attempt to introduce competition not

only proved unsuccessful, but the new contract meant PA&E would

operate under two distinct contracts. Any thoughts of a second try

at competition were quietly laid aside, and-the following year the

Army returned to a single contract.

In 1967 PA&E's activities were extended into I Corps following

deployment of substantial numbers of Army units into the area, which

had been primarily a Marine Corps and Navy zone of operations.

Although the Navy was providing logistical support for I Corps, it

was not in a position to support all Army installations.

In 1970, following major shifts in U.S. operations, logistical

responsibility for I Corps was transferred from the Navy to the

Army. Consideration was given to extending the PA&E contract to

cover all of the area, but the decision was made to negotiate a

contract with Philco-Ford to continue in the areas where they had

been working under contract to the Navy. This arrangement

facilitated continuity of operations but had the disadvantage of

resulting in two different contracts and contractors to supervise.

[93]

Experience in Vietnam highlighted many administrative, regulatory,

and other constraints, which indicated areas where improvement was

required. Vietnam was the first conflict in which peacetime Army

budget regulations had been stringently applied in a combat zone.

Many of the peacetime regulations applicable to facilities

engineering were necessarily prohibitive in nature and cumbersome in

application. Designed to minimize the diversion of utilities

engineering resources and to avoid certain statutory violations, the

application of these regulations in a combat zone greatly inhibited

the effectiveness of facilities engineering support by both the

contractor and the utilities detachments. Further examination of

these regulations as well as the Department of Defense directives

and the laws on which they were based is required to achieve greater

flexibility and responsiveness under future combat conditions.

The contractor, PA&E, frequently drew criticism for

overstaffing. Much of his staffing requirements, however, resulted

directly from the requirement that he organize, staff, and manage

his efforts strictly in accordance with Army regulations. (Chart

6)

This resulted in much of the contractor's effort going into work

management and production control. While the principles of work

management are an inherent part of effective operations under any

conditions, the amount of effort expended in the preparation of

detailed schedules and work plans was of questionable value under

the turbulent conditions which prevailed. There was a distinct

advantage in having the contractor follow Army regulations in

organizing and managing his force in that this facilitated the

control and monitoring by the contract officers, but here too

consideration should be given to adopting simplified procedures for

combat conditions.

A major problem that persisted throughout the conflict, largely

because of the rapid turnover of military personnel, was the general

lack of facilities engineering experience. The one-year tour of duty

was necessary from a morale standpoint, but it had an adverse effect

on the operations of the engineer detachments and on contractor

supervision. Most officers assigned to facilities engineering duty

in Vietnam lacked former experience, and it normally took much of

their one-year tour to become knowledgeable in facilities

engineering regulations and requirements. The Vietnam experience has

highlighted the need for a broader base of both officers and

enlisted men with facilities engineering training and experience.

Perhaps the greatest difficulty in the contractor's operations

stemmed from the problems he had in obtaining the necessary

government-furnished supplies and equipment-problems which were not

resolved until late in the conflict.

[94]

[95]

Despite these difficulties, the facilities engineering support of

combat forces in Vietnam was an undertaking successfully carried out

on a scale never before seen in a combat zone. The rest of this

chapter will discuss a few of the special problem areas.

While primarily contracted for facility operation, maintenance,

and repair, PA&E was used extensively to accomplish construction

of minor facilities during the major period of the troop buildup

from mid-1965 to mid-1968. Before the buildup, the small PA&E

force was primarily engaged in maintenance and repair of leased

facilities. As more and more troop units arrived in Vietnam, the

most urgent requirements were to construct defenses followed by

troop and support facilities. Urgent requirements existed for

cantonments, airfields, depots, repair shops, and the utilities

systems needed to service them. Because of its construction

capability, Pacific Architects and Engineers was called upon to

provide help in small operations and maintenance funded (under

$25,000) projects. Paradoxically, although much of its effort went

into construction, the terms of the PA&E contract did not permit

the contractor's employment on new construction funded work. This

meant that he could not construct many of the facilities needed for

his own use, which would have increased his over-all effectiveness.

By the end of 1967 the increased capabilities of the construction

contractors and construction troops made it possible for Pacific

Architects and Engineers to concentrate on facilities engineering.

The sharply increased demand for facilities engineering made

redirection of PA&E effort imperative as more new facilities

went into use and more troops arrived in the theater. While during

1965 and 1966 the contractor expended as much as 80 percent of his

effort on new construction, this figure dropped to 25 percent by the

middle of 1968 and to below 15 percent in subsequent years.

The varying standards of construction and the absence of a

standard for maintenance and repair proved troublesome throughout

the conflict. Although the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam

published over-all standards, wide variations existed. Standards

ranged from tent frames and Southeast Asia huts to elaborate

air-conditioned, pre-engineered facilities with high-voltage

electric distribution systems and modern water and sewage systems.

The extent of facilities engineering support received by individual

installations depended on what local commanders needed and on what

facilities they succeeded in getting built. Until very late in the

conflict, there were no countrywide standards for planning

facilities engineering support. As a result, resources were often

not equitably distributed.

Fire protection was certainly adequate at Army installations

[96]

VIETNAMESE FIREFIGHTER ignores risk to fighting petroleum fire

at Long Binh.

throughout Vietnam. Fire companies were manned primarily by

PA&E, although there were some military firefighting

detachments. On a visit in 1969, representatives of the Office of

the Chief of Engineers pointed out that there were far too many fire

companies and fire trucks in the theater. Further analysis by the

Army Engineer Construction Agency led to a substantial reduction in

fire companies and the cancellation of all outstanding requisitions

for fire trucks. Although fire protection was possibly overstressed,

fire prevention was given inadequate attention. While temporary

structures appropriate to a combat zone were constructed with

combustible materials like plywood and low-density fiberboard, fire

hazards could have been appreciably reduced by proper building site spacing. Still, the use of combustible interior partitions and other

interior finishes and nonexpert installation, extension, and

modification of electrical systems created serious fire hazards. The

lesson is evident-more emphasis must be given to fire prevention.

Control of insects, rodents, and other pests was a particularly

challenging problem. Vietnam lacks all but the most basic health and

sanitation safeguards; malaria and the plague are endemic. Vigorous

efforts by facilities engineering entomology teams and the rigid

enforcement of health and sanitation rules turned military bases

into "islands of health in a sea of disease and

pestilence." The return of retrograde cargo from Vietnam raised

the danger of Asiatic insects and rodents being brought back.

Careful and thorough cleaning of this cargo and treatment with rat

poison and insecticide dust-as much as 112 tons per

month-effectively eliminated this danger. Losses of foodstuffs in

storage from insect infesta-

[97]

tion amounted to millions of dollars annually. During 1970, new

control techniques for treatment of stored foodstuffs in CONUS

before shipment and in Vietnam after receipt were adopted.

Fumigation of railway cars in transit from the mills began in

September 1970. Experience in the United States to date indicates

that these procedures will reduce losses of stored foods by as much

as 98 percent.

Chief among the lessons learned from Vietnam was that the

requirements for facilities engineering support in future conflicts

must be anticipated during contingency planning, inasmuch as these

requirements represent a substantial portion of the resources

required to support such an operation-the total force dedicated to

facilities engineering (over 25,000) approached the combined

strength of the two engineer brigades deployed to Vietnam (about

30,000). The feasibility and, under similar circumstances, the

desirability of providing the major portion of this force by

contract was demonstrated in Vietnam. Our experience also clearly

demonstrated the need for the Army to maintain, in its active force

structure, an adequate number of military personnel trained in

facilities engineering to provide management and supervision of

contractor and direct-hire civilian maintenance forces and to man

sufficient numbers of military facilities engineering detachments to

ensure continuity of essential operations in emergency situations.

[98]

page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents