- Chapter VI:

-

- Facilities Construction

-

- The vast construction effort designed to provide Vietnam with ports and

airfields capable of accepting freight carriers did not encompass all that

was necessary to provide for adequate handling of matériel once it did arrive.

Mass movement of supplies and shortage of storage areas and of construction

capability caused large quantities of supplies in early shipments to be stored

in the open. This in turn caused rapid deterioration and losses. A more balanced

effort of depot and port construction would have prevented some of the supply

problems experienced later. However, the construction resources available

had to be used where they were most urgently needed at the time. The tactical

decision to bring in combat troops ahead of support units was necessitated

by the enemy situation and political decisions which greatly complicated the

problem of logistic and construction support.

-

- The limited local facilities available for the buildup were not constructed

to serve as warehouses, and their use precluded a well organized supply effort.

In August 1967, 25 percent of the required covered storage space was available,

and another 43 percent was under construction. The lack of covered storage

space was a prime contributing factor to deterioration of stocks. Space limitations

and multiple storage locations were a major cause of lost stocks, poor inventory

counts, and inefficient warehouse operations. In a climate like Vietnam's,

high priority should have been given to early construction of covered storage

space.

-

- In April 1966, when the Qui Nhon Support Command was elevated to a depot

command coequal with Cam Ranh, requirements were increased for storage facilities.

Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen was then called upon to construct them; simultaneously,

much of the work on depot facilities at Pleiku was turned over to RMK. The

depot facilities requirements for Cam Ranh Bay were still not sufficient.

-

- Perishable items in Vietnam were phased into the menu faster than storage

and handling could be provided. Means of remedying this situation included

leasing commercial facilities, using banks of hastily erected 1,600 cubic

foot refrigerator boxes, and using

- [71]

- offshore floating refrigerated storage. In September 1966 two cold storage

warehouses were completed in Da Nang. In 1967 cold storage warehouses were

completed in Cam Ranh Bay and Qui Nhon. In July 1969 the first section of

the Long Binh cold storage warehouse was placed in operation with the rest

becoming operational in October 1969. The construction of cold storage warehouses

was definitely more economical than leasing facilities or using floating storage

for extended periods of time, but cold storage facilities had to wait their

turn among other priorities.

-

- Since local ice production was limited, sixteen ice plants were brought

into Vietnam in January 1966 and an additional twenty-four ice plants in July

1966. Because construction effort was lacking, erection of some of these plants

was delayed, but many were erected by the facilities contractor, Pacific Architects

and Engineers. Each ice plant was capable of a daily production of fifteen

tons; yet, because local operating personnel were untrained, production was

consistently below the plant's rated capacity.

-

- To provide the wide range of dairy products in the quantity required in

A rations, recombining milk plants were built in Vietnam. A Foremost Dairy

plant began, production in Saigon in December. 1965. Under a contractual agreement

with the Army, Meadow gold Dairies constructed a plant in Cam Ranh Bay, which

began production on 15 November 1967, and a plant in Qui Nhon, which began

production on 4 February 1968. After the cost was amortized, ownership was

to be transferred to the U.S. government. By assuming the risk of operations,

the Army obtained the Meadow gold product at a lower cost (including amortization

costs) than the Foremost product. But in either case, the attempt at improving

living conditions was appreciated.

-

- In early 1966 considerable construction effort was directed into the upgrading

of living facilities from field to intermediate standards. By pouring concrete

tent slabs and constructing tropicalized buildings for mess halls, dispensaries,

showers, and latrines, the transition was begun. In many cases, engineer troops

prefabricated and erected buildings; in other cases, facilities were built

by contract with Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen and Pacific Architects and Engineers,

or by self-help with the technical assistance of engineer units.

-

- By February 1966 cantonment construction was well under way. At Qui Nhon

a 900-man cantonment for the logistical command and a 50-man cantonment for

a signal relay site were in process. A division cantonment was under construction

at An Khe. Cam Ranh's construction included a 6,400-man logistics camp and

a 2,500-man engineer cantonment. At Phan Rang a 4,500-man can-

- [72]

- tonment was going up. Quonsets on pads for II Field Force head quarters

were being constructed at Long Binh. Near Di An a 2,950-man cantonment for

1st Division units was in process. By mid-April 1966, construction had been

expanded to include a 1,600-man cantonment at Dong Ba Thin, a brigade cantonment

at Long Thanh, a 4,500-man cantonment at Lai Khe, and a drainage and roadnet

at Cu Chi. By June 1966 in Qui Nhon, materials for cantonment construction

were also supplied to a newly arrived Korean unit. Additional troop and contract

construction at his time included a camp for a Korean headquarters unit at

Nha TraZ and a 4,500-man Australian cantonment at Vung Tau.

-

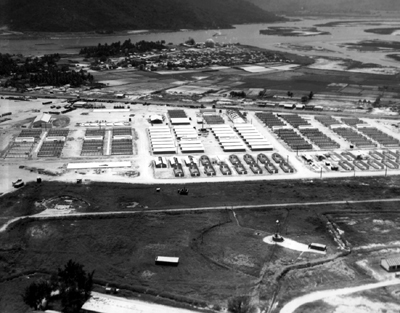

- The decision to station U.S. ground troops in the delta south of Saigon

led to the construction of a base camp at Dong Tam-a major undertaking because

the site had to be elevated several feet. The dredging operation alone required

several months. Construction began in mid-1966, and the first occupants moved

in early in 1967. The first units arrived on LST's and other, river craft

in a carefully planned operation. Concurrent with the over-the-beach arrival

of combat units, engineer units arrived by road and replaced an Eiffel bridge

on the highway between Dong Tam and My Tho with a Bailey bridge. This opened

up the road to Dong Tam, which was at this time the base camp for one brigade

of the 9th Infantry Division. Another brigade was quartered on reconditioned

barges provided by the U.S. Navy. These two brigades comprised the riverine

assault group, which carried American forces into the delta.

-

- By early 1967 approximately one quarter of the troops in Vietnam were in

billets constructed by the Army Engineer Command, Vietnam. By about the same

time 2,500 structures were built using self-help. Engineers provided equipment

and supervision and constructed any facilities requiring special skills. The

work began with the fabrication of major structural sections at engineer prefabrication

sites. The engineer unit erected the first building while the self-help unit

observed. After this demonstration, the using unit would designate work crews

and begin construction. A construction engineer inspector was assigned to

all projects to ensure proper workmanship and construction methods, while

engineers installed drainage facilities, did excavation and grading, and poured

more concrete pads. The self-help program evolved from an insatiable demand

for engineer and construction resources. Self-help provided units with facilities

sooner than would otherwise have been possible.

-

- A study made by the U.S. Army, Vietnam, in 1966 recognized that cantonment

construction involved more than clearing an area. Roads, billets, mess halls,

latrines, showers, dispensaries, helicopter pads, water towers, chapels, and

post offices would also have to be

- [73]

- QUARTERs rise on concrete slabs at Long Binh.

-

- built sooner or later. This study defined a cantonment and determined the

costs per man for each cantonment category. It also provided initial cost

estimates for a typical infantry division cantonment constructed by troops

at the following costs per man:

-

| Field |

Intermediate |

Temporary |

| $240.00 |

$560.00 |

$940.00 |

-

- Subsequently, on 20 October 1966, MACV Directive 415-1 establishing revised

construction standards for cantonments in Vietnam was issued.

-

- In 1967 General Westmoreland on a visit to Phan Rang expressed concern about

the extent of new construction under way for units assigned to the 101st Airborne

Division. He pointed out that much of the work was unnecessary because the

101st was almost constantly in the field and did not make full use of the

buildings already erected. After his visit, General Westmoreland ordered all

construction stopped at Phan Rang. Lieutenant General Bruce Palmer, Jr., then

Deputy Commanding General, USARV, established a base development study group

in August 1,967 to study further the problem throughout the Army area. He

asked the group to evaluate all base camp construction in light of current

strengths and austere requirements. As a result of this review, numerous

- [74]

- reprograming actions were made to assure that only essential base construction

continued.

-

- In late September 1967 General Palmer approved the "hotel" concept

recommended by the study group. The essence of this concept was that in any

given base camp the Army would not try to accommodate every man stationed

there, since a significant part of every maneuver unit would, always be in

the field. Capacity would be governed by the size of the population inhabiting

a particular camp on a continuous basis. The hotel concept did present some

problems in storage and maintenance facilities, however, since they were not

initially constructed to accommodate all of the equipment and property left

behind by units gone to the field.

-

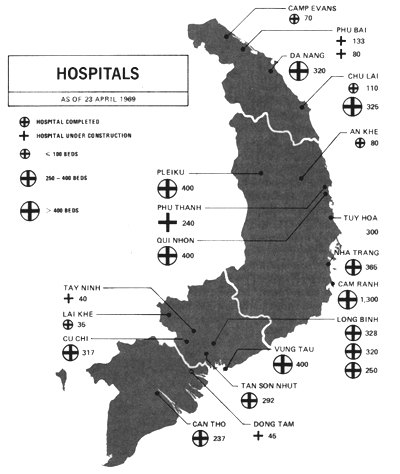

- The hospital program in the meantime consisted of a 1,000-bed convalescent

hospital, which later expanded to 2,000 beds at Cam Ranh Bay, two 500-bed

hospitals at Qui Nhon, one 500-bed hospital at Vung Tau, and a mobile surgical

hospital at An Khe. In addition, various smaller facilities and field hospitals

were being built throughout the country. Many of these hospitals were constructed

by joint troop and contractor efforts. It was planned that most of the major

troop cantonments or base complexes would have either a 60-bed surgical hospital

or a 400-bed evacuation hospital. Field hospitals and convalescent centers

were also constructed. (See Map 9.)

-

- When the 45th Surgical Hospital arrived at Tay Ninh in October 1966, it

was the first medical unit, self-contained, trans-

- SPIDER-LIKE DUCTS provide air to MUST hospital complex from centralized

air-conditioning units.

- [75]

-

- portable (MUST) hospital in Vietnam. This hospital was installed in a 500x1,000-foot

area which contained all hospital facilities, billets for medical personnel,

mess halls, and helipads. The hospital, developed by Garrett Air Research

Company for the Army Medical Corps, was erected on a 200x300-foot laterite

hardstand. The unit consisted of three separate packages, each weighing about

4,000

- [76]

- pounds, and was transportable by 2i/2-ton trucks. Enemy mortar fire showed

that these facilities required additional protection; they were reinforced

to withstand direct hits by 82-mm. mortar rounds.

-

- Beginning in 1965 the, administrative elements used existing facilities

primarily in and around Saigon. However, as the buildup continued and forces

spread throughout the country, more administrative facilities became a necessity-especially

near logistical and major command centers. This construction was normally

accomplished by the contractor or a contractor-troop combination. Administrative

centers were built in Saigon, Tan Son Nhut, Long Binh, Cam Ranh, Qui Nhon,

and Nha Trang.

-

- Early in 1967 General Westmoreland began a campaign to reduce materially

U.S. troop presence in major cities-especially Saigon. Under the direction

of the MACV J-4, a program with the code name MOOSE (move out of Saigon expeditiously)

was established. The program, however, was extremely difficult to implement.

The first problem was to locate additional space outside of the city in an

area where the same mission could be performed. Commanders were reluctant

to leave the Saigon area and be very far away from the center of activity,

that is, Military Assistance Command and Joint General Staff headquarters.

Whenever a unit moved from leased quarters, there was always a tendency for

other units, which were crowded, to expand into the vacated space.

-

- Nevertheless by mid-1967, approximately half of the Army personnel was moved

out of Saigon and relocated at the Long Binh complex. Personnel who remained

were located primarily at Tan Son Nhut or were involved in activities which

required close proximity to the air base or MACV headquarters. On 15 July

1967, USARV headquarters officially announced its move to Long Binh while

construction crews still hurried to finish the facilities. Engineer troops

graded and sodded the headquarters area to control erosion; established temporary

water supply points; built three officers' mess halls, a VIP heliport, latrines

and showers for enlisted personnel, and three trailer courts for general officers,

VIP's, and senior colonels; erected flag poles; graded parking lots; and finished

the access roads to the new USARV headquarters. Meanwhile, the contractor

was completing the last headquarters building and working on the waterborne

sewage system.

-

- As headquarters and base camps grew, the entire Pacific Command communications

system was expanded and upgraded. The environment and nature of operations

gave rise to an extensive communications network within Vietnam. High-quality

communications were required not only in Southeast Asia and by deployed combat

forces in the western Pacific, but by other support elements

- [77]

- scattered throughout the Pacific Command. An integrated communications system

in support of operations in Vietnam was established, which extended from Hawaii

to Korea in the north, Vietnam and Thailand in the south, and along the island

chain from the Philippines to Japan.

-

- In order to implement these systems, the construction of new semi-fixed

facilities at various locations throughout Vietnam was necessary. This was

accomplished both by troops and by the contractors. Installation of tools,

test equipment, and work areas was performed by contract with Page Communications

Engineers, Inc., whose services facilitated installation of fixed communications

equipment during the buildup's initial stages and provided continuity of operations

and technical expertise while the military were engaged elsewhere.

-

- Without contractor support in the construction and installation of the fixed

communications systems in Vietnam, effectiveness would have been considerably

lessened. The military services, unfortunately, have relied on contractor

support in the United States in recent years to such an extent that the services

have failed to train personnel and equip sufficient units to perform these

tasks for themselves. Other benefits were provided by the contractor effort

in the construction, installation, operation, and maintenance of fixed communications.

Contractor personnel remained in the country longer than the one-year tour

served by military personnel, thus lending more experience and continuity

to the job. The contractor also generally had access to other than military

supply channels, and this facilitated his obtaining urgently needed repair

parts and other supplies from any source directly.

-

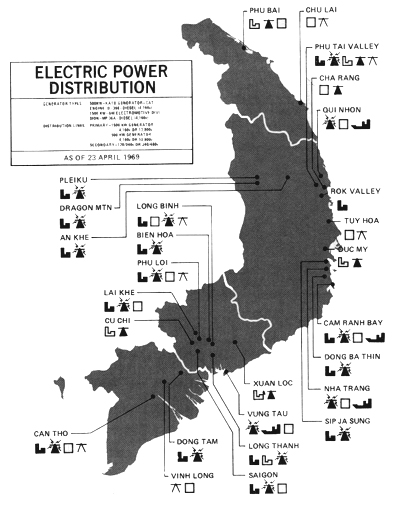

- For each major base constructed, and to a lesser extent for each of the

smaller bases, the Army had to provide electrical power to run the unending

variety of electrical machinery employed by a field army. There was a severe

general shortage of commercial power throughout Vietnam. As units arrived

in the country, they often had to get along with their own tactical generators.

As cantonments were built and refrigeration plants, computer systems, communications

sites, and similar facilities were added, standard Army generators simply

could not meet the demand. So in 1966, 600 nontactical generators arrived

from Japan, and another 722 were shipped from the United States. These generators

ranged in size from 100 to 1,500 kilowatts: In March of the same year, a contract

was awarded to the Vinnell Corporation to withdraw eleven T-2 tankers from

the Maritime Reserve Fleet and convert them to floating electric power generating

barges. Five of the converted ships were capable of generating 3,100 kilowatts,

and six 4,300 kilowatts.

- [78]

- Five of the ships were eventually anchored at Cam Ranh Bay (15,500 kilowatts),

and two each were located at Qui Nhon, Vung Tau, and Nha Trang (8,600 kilowatts

at each location). In April 1966 the Vinnell Corporation began work on land-based

electrical generation and distribution systems for Cam Ranh Bay, Qui Nhon,

Nha Trang, Vung Tau, and Long Binh. This contract was modified in 1967 to

provide service at twelve additional sites.

-

- Despite these projects, demands for electrical energy continued to exceed

supply as more and more sophisticated electrical equipment and machinery arrived

in Vietnam, standards of living grew higher, and nice to have but largely

unnecessary appliances-hot plates, toasters, air conditioners, coffee makers,

and the like-appeared in post exchanges.

-

- Air-conditioning equipment was also a critical item. Facilities requiring

a controlled environment such as field hospitals and computer centers made

large-scale installation of air conditioning necessary. There were widespread

efforts to obtain air-conditioning equipment for quarters, open messes, and

administrative areas. In an effect to reduce the diversion of air-conditioning

equipment from essential purposes and also to reduce the maintenance load

placed upon PA&E by widespread installation of air-conditioning equipment,

USARV established a control system to ensure that air-conditioning equipment

was not issued unless a control number

-

- FLOATING POWER PLANTS. Five tanker-generators ships providing power

to Cam Ranh facilities

- [79]

- was assigned indicating that the equipment had been approved for a specific

project.

-

- Long-range planning for joint use of power systems had been further complicated

by the fluctuation of troop deployments. Assets were constantly being reprogramed

as planned unit base camps were changed in either size, location, or priority.

In Nha Trang, for example, it proved impractical to service Air Force facilities

from the planned T-2 tanker power plant, since the Air Force installation

was based on a different primary system. At Cam Ranh the Army complex consisting

of a convalescent center, replacement center, rest center, and other facilities

was located a long distance from the T-2 electrical plant. It was also separated

from the main Army installation to the south by a concrete runway. The Air

Force was faced with the problem of serving its facilities on either side

of the runway. In order to avoid constructing two Air Force power plants and

a separlite Army plant, an agreement was negotiated under which the Air Force

would construct one power plant north of the runway and provide 5,000 kilowatts

of power to the Army complex, while a like amount of power would be supplied

to Air Force units south of the runway from the Army system.

-

- A review of the T-2 power program in early 1967 showed slow progress. At

Cam Ranh Bay five converted T-2 tankers were in position. Two were connected

to the distribution system with a third to be tied in within three weeks.

The primary distribution system was nearly completed. Power was being delivered

to areas where the secondary system was installed. The remaining work consisted

of completing the secondary distribution system, the 8,800kilowatt land-based

power plant, and the switching station. The completion date would be 1 May

1967. Total power was 33,800 kilowatts.

-

- Two T-2 tankers for Qui Nhon were not yet positioned in early 1967. Dredging

of the mooring site was in progress. The contractor was in the early phases

of constructing pole lines. Completion was set for 1 July 1967. Total power

would be 15,000 kilowatts. At Long Binh T-2- power ships had been scratched

from the project and relocated. The Vinnell Corporation was mobilized and

had started pole-line construction. Generator pads were being poured, and

the first increment of power was scheduled for April 1967. Total power delivered

would be 30,000 kilowatts with provisions for adding on 15,000 kilowatts.

Two T-2 tankers for Nha Trang were in Vietnam but not positioned. Power output

was to be 15,000 kilowatts. At this time one of the T-2 tankers was on hand

for Vung Tau, and the last of the eleven ships was expected to depart the

United States shortly. (Map 10 and Table 3)

- [80]

- MAP 10

ELECTRIC POWER DISTRIBUTION

- Real-estate problems were encountered at the various sites because of poor

co-ordination. Vinnell had been doing the design work for distribution systems

in the United States and had not made field checks on the positioning of switching

gear, transformer stations, power lines, or other factors which would affect

the area that the power grid would occupy. The contracting officer's representa-

- [81]

-

| LOCATION |

IN PLACE |

UNDER CONSTRUCTION |

PROPOSED |

Generators, KW

|

Power Barges,

KW

|

Total

KW |

Distribution,

LF

|

Completion

Date |

Generators, KW

|

Total

KW |

Distribution,

LF

|

Estimated Date

of Completion |

Generators, KW

|

Total |

Distribution,

LF

|

Estimated Date

of Completion |

| 500 |

1500 |

5000 |

7500 |

Primary |

Secondary |

500 |

1500 |

Primary |

Secondary |

500 |

1500 |

Primary |

Secondary |

| Phui Bai |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

3,000 |

1,200 |

1,500 |

APR 69 |

3 |

|

1,500 |

|

|

(5) |

| Chu Lai |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

3,000 |

55,000 |

52,000 |

DEC 69 |

| Cha Rang |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26,000 |

19,030 |

AUG 69 |

5 |

|

2,500 |

|

|

SEP 69 |

| Pleiku-Log Depot |

4 |

|

|

|

2,000 |

42,000 |

19,000 |

JAN 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pleiku-Dragon MT |

|

6 |

|

|

9,000 |

74,480 |

68,000 |

JAN 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| An Khe |

|

6 |

|

|

9,000 |

114,650 |

74,500 |

NOV 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phu Tai Valley "F" |

|

3 |

|

|

4,500 |

39,045 |

19,180 |

JAN 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phu Tai Valley "R" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

4,000 |

25,000 |

20,000 |

JUL 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Phu Tai Valley "G" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,000 |

6,000 |

(1) |

| Qui Nhon |

|

|

|

2 |

15,000 |

122,000 |

31,700 |

FEB 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5/1 |

9,000 |

|

|

(4)/(5) |

| Rok Valley |

|

4 |

|

|

6,000 |

63,200 |

67,840 |

JAN 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tuy Hoa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

4,500 |

17,000 |

40,000 |

SEP 69 |

| Duc My-Ninh Hoa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

1,500 |

53,000 |

30,000 |

JUN 69 |

69 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sip Ja Sung-Rok Nha Trang |

6 |

|

|

|

3,000 |

36,600 |

28,800 |

NOV 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nha Trang |

|

|

|

2 |

15,000 |

86,200 |

25,400 |

FEB 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12/3 |

|

7,500 |

|

|

(4)/(5) |

| Dong Ba Thin |

4 |

|

|

|

2,000 |

17,000 |

11,000 |

DEC 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cam Ranh Bay |

|

|

5 |

|

*33,800 |

294,700 |

104,400 |

MAR 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

13,500 |

|

|

(4) |

| Lai Khe |

4 |

|

|

|

2,000 |

100,000 |

95,040 |

NOV 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

2,000 |

|

|

(3) |

| Phu Loi |

3 |

|

|

|

1,500 |

14,000 |

3,000 |

NOV 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

1,500 |

16,000 |

25,000 |

JUL 69 |

| Cu Chi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

6,000 |

62,000 |

100,000 |

JUN 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bien Hoa |

|

3 |

|

|

4,500 |

47,470 |

37,700 |

DEC 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Binh |

|

21 |

|

|

31,500 |

406,000 |

171,000 |

DEC 68 |

|

|

|

25,000 |

16,000 |

|

|

6/3 |

13,500 |

|

|

(4)/(5) |

| Xuan Loc-Black Horse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

3,000 |

42,000 |

50,000 |

SEP 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Saigon-3rd fld Hosp. |

3 |

|

|

|

1,500 |

|

|

JUL 67 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

1,000 |

|

|

(5) |

| Saigon-New Port |

3 |

|

|

|

1,500 |

50,000 |

59,000 |

NOV 67 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

1,500 |

|

|

(5) |

| Long Thanh |

|

3 |

|

|

4,500 |

94,000 |

90,000 |

DEC 68 |

|

3 |

4,500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dong Tam |

12 |

|

|

|

6,000 |

37,000 |

37,000 |

MAR 69 |

|

|

2,000 |

|

|

APR 69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vung Tau |

|

|

|

2 |

15,000 |

92,000 |

86,700 |

DEC 67 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

6,000 |

|

|

(4) |

| Vinh Long |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3/1 |

|

2,000 |

18,000 |

18,000 |

SEP 69/(3) |

| Can Tho |

4 |

|

|

|

2,000 |

44,000 |

22,000 |

DEC 68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

2,000 |

44,000 |

22,000 |

JAN 70 |

| Total |

43 |

46 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

35 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

57/4 |

23/4 |

|

|

|

|

-

- (1) Awaiting USARV Decision on Cancellation. (2) Awaiting MACV Decision.

(3) Awaiting MACV Approval. (4) Awaiting OSD Approval. (5) Future Requirement

* Including 8 EA. 1,100 KW Land Based Generators.

- [82]

- tive in Vietnam subsequently initiated the appropriate real-estate acquisition

procedures and managed to co-ordinate the space available with the size of

the power system.

-

- At division base camps, it was extremely difficult to provide enough power

with small generators. Practically all of the large bases eventually had high-voltage

central power systems operated by one of the contractors. This proved very

efficient and satisfactory in the long run; however, the system would be extremely

difficult to operate and maintain if untrained military units had to be used.

-

- Since water supply has a very direct effect on the health and the welfare

of troops, as various fixed Army installations in Vietnam were being created,

expanded, and improved, so was the water supply. When U.S. forces began arriving

in Vietnam, it was necessary to rely on water sources that were immediately

available; these included lakes, rivers, streams, shallow wells, and occasionally

municipal systems. These surface water sources were all subject to contamination

and were of a generally poor quality, and the water obtained required extensive

treatment. Existing well locations usually required hauling water over congested

routes for long distances, and since water supply points were usually located

outside cantonment areas the enemy could interdict them and deny their use.

-

- Water was treated with tactical erdlators, which provided coagulation, sedimentation,

filtration, and chlorination. Although the annual rainfall is heavy in Vietnam,

and there are abundant surface water sources, the amount of water available

for troop consumption was limited by treatment capability. To overcome these

disadvantages, a massive deep-well drilling program was initiated. It was

anticipated that these wells, producing water from deep underground sources,

would provide water of better quality so that no treatment other than chlorination

would be required.

-

- The deep-well program did improve water quality, and water production was

increased. The aim was fifty gallons per man per day. Supply sources were

relatively secure, since the new wells were located within .cantonment areas.

The relocation of wells and water points and the improved distribution systems

released erdlators and purification units for use by tactical units in those

areas where surface sources were still in use.

-

- The well-drilling program made use of both military and civilian contractor

drilling teams. The first phase of the program in early 1967 envisioned the

drilling of 180 wells throughout Vietnam with a cost of approximately $5.4

million. At that time there were seventeen civilian, five Army, and four Navy

well-drilling rigs and teams working in the country. In addition to providing

water, this project

- [83]

- furnished important hydrological information on subsurface conditions throughout

the country. From this information, the second phase of the program was formulated,

and additional wells were dug. A production goal of fifty gallons per man

per day for intermediate and field cantonments and a hundred gallons per man

per day for temporary cantonments was achieved in most locations.

-

- Many problems were encountered in implementing the well drilling program.

Contractors had difficulties in obtaining permission for their employees to

enter Vietnam and trouble assembling supplies. The Army teams lacked experience

and faced a continual shortage of well supplies such as casing and screen.

However, through practice and various expedient methods the problems of the

Army were finally overcome.

-

- Contract well-drilling was phased out on 15 April 1967. Contractors had

completed approximately 160 of the 300 wells programed. The rest of the program

was carried on with four Seabee operated drill rigs and seven Army drill rigs.

Together they drilled 68 additional wells, bringing the number of wells to

248. This completed about 75 percent of the well-drilling program. These Seabees

left for the United States on 30 September 1967, and the remainder of the

program was completed by Army detachments.

-

- Central waterborne sewage systems were originally provided at very few locations.

The burn-out latrine, locally manufactured from a 55-gallon drum cut in half

and partially filled with diesel fuel, was used at sites not located within

or near major cities. Burn-out latrines were inexpensive to construct and

operate and met field standards of sanitation. But morale was adversely affected

by this primitive outdoor plumbing with its inevitable odors and by the dense,

foul, black smoke generated during burning. Troops were particularly disgruntled

when they had to burn out latrines in areas restricted to Vietnamese workers.

Morale also suffered considerably in areas such as Cam Ranh Bay where on one

side of the bay the Army had burn-out latrines, and on the other side the

Navy and Air Force had a central system.

-

- In July 1967. a sewage lagoon for primary and secondary treatment of sewage

for a population of 14,000 was constructed at Long Binh. Sewage lagoons, when

properly operated, performed very well. The decomposition of sewage in lagoons

eliminated both objectional odors and appearance.

-

- Due to heavy rainfall and the soil encountered in Vietnam, normally used

treatment facilities were not adequate. The possible exception to this was

the trickling filter. Leaching fields and septic tanks did not always work

properly, basically due to the general imperviousness of the soil. Oxidation

ponds were not always prac-

- [84]

- LARC V, amphibious cargo carrier.

-

- tical because the excessive land required was not always available due to

heavy rainfall. These problems were further compounded by the high water table,

which in most areas of Vietnam is within twelve to eighteen inches of the

surface during the monsoon season.

-

- Sanitary fill areas were established for all areas as land could be made

available. Equipment for the operation of the fills was borrowed from somewhere

else. Sewage disposal is still provided in most places away from heavily populated

areas by burn-out latrines or septic tanks. Local-hire personnel handle latrines,

while facilities contractor personnel pump septice tanks and operate the few

waterborne sewage distribution systems.

-

- During early stages of the buildup, U.S. military forces experienced other

supply distribution problems. Ammunition supply was particularly critical

because of the limited adequate storage facilities and great dispersion of

forces. In March 1965 the only ammunition supply point in Vietnam was at Tan

Son Nhut. By the end of the year eight air supply points had been constructed

to receive emergency loads of ammunition in operations areas. Ships were waiting

to unload, and there was an urgent requirement for the expansion

- [85]

- of facilities. Due to their strategic locations, heavy traffic moved into

the ports of Saigon, Qui Nhon, Da Nang, and Cam Ranh Bay. All deep-draft vessels

entering these ports had to be discharged offshore, and the ammunition was

brought ashore by lighters.

-

- The situation became critical in December 1965, and steps were taken to

relieve a 48,000-ton backlog, which was distributed at the ports of Saigon,

Qui Nhon, Da Nang, and Cam Ranh Bay. Construction of a deepwater ammunition

pier at Cam Ranh Bay started late in 1965, and improvement and expansion of

ammunition offloading points at other ports eased the crisis somewhat, but

even as late as 1969 facilities were still not totally adequate. Procurement

of unnecessary real estate for dispersed storage of the quantities of ammunition

shipped to Vietnam took time. Waivers were necessary to permit the continued

on-the-ground storage of ammunition, since it was not possible to meet all

safety criteria. Construction of adequate new ammunition storage facilities

was subject to military construction procedures, priority allocations, and

required lead times. The magnitude of the storage problem can be illustrated

by citing stockage objectives established by the services during the peak

of U.S. force buildup. These levels required in the country were 295,000 tons

for the Army, 59,000 tons for the Air Force, and 56,000 tons for the Marine

Corps. The total of 410,000 tons included neither Navy requirements nor provision

for the large quantities of suspended and unserviceable ammunition requiring

storage pending retrograde. Even then stockage objectives were often exceeded.

-

- BARC, the heaviest of the amphibious lighters.

- [86]

- Because of the difficulty in obtaining adequate real estate, a modular concept

of storage, which had been developed by the Air Force, was approved by General

Westmoreland for use in the combat zone. In application, a module was comprised

of 'a maximum of five cells, each separated by barricades. Each cell contained

100 tons of explosives. This allowed the storage of up to 500 tons of explosives

in a single contiguous module. Separate revetments were limited to 125 tons

each. This resulted in decreased land requirements and reduced the distance

requirement between explosive storage areas and other facilities.

-

- Although the modular ammunition storage system provided a savings in space,

it concentrated large quantities of ammunition in small areas and made for

a greater hazard. The loss of several ammunition supply points due to fire

and enemy action justified the need to continue attempts to find suitable

methods for improving ammunition storage. The consequences of not taking action

were well illustrated in the loss of the ammunition supply point at Da Nang

on 27 April 1969 in which approximately 39,170 tons of ammunition valued at

$96 million were lost in one attack.

-

- Construction in Vietnam was only partly a process of converting bulk raw

materials into facilities. The American construction industry conceived pre-engineering

and prefabrication as a means of minimizing design requirements and increasing

on-site productivity. Although building codes and labor agreements have slowed

the adoption of prefab techniques in the American civilian sector, the services

were under no constraints in the theater of operations. From a military viewpoint,

a prefabricated package can be deployed at least as rapidly as bulk construction

materials; it can be erected faster with fewer men; and its relocatability

can reduce additional material requirements in redeployments. The shortage

of engineer construction units in a future Vietnam-size contingency indicates

that greater use must be made of this type structure.

-

- In early 1966 a requirement for 12,000 pre-engineered buildings was determined

for Vietnam. Specifications for some prefab structures were outdated and the

buildings could not be provided expeditiously. Efforts were initiated to develop

specifications and procure needed standardized pre-engineered buildings. By

late 1966 both the Army and the Air Force were using the BUSH (Buy U.S. Here)

Program and purchasing buildings for the Far East. The buildings eventually

procured were of many different makes and types. These pre-engineered and

prefabricated commercial-type facilities were used extensively in Vietnam

for shops and warehouses in logistics and air base complexes. They were also

used to meet administrative requirements in some of the large complexes,

- [87]

- COMPLETE SELECTION of wood, aluminum, and steel buildings under construction.

-

- such as the Military Assistance Command headquarters and the Long Binh headquarters

of the U.S. Army, Vietnam. In some smaller complexes such as the Da Nang Supply

Depot where real estate and time limitations dictated rapid erection of multistory

structures, they also found users.

-

- One type of prefabricated building used widely in the Long Binh area was

the advanced design aluminum military shelter, an Australian development,

popularly known as ADAMS huts, which were of all-aluminum construction and

featured louvered sections in walls and windows for maximum ventilation. While

ADAMS huts were easily erected on concrete slabs, they required the drilling

of many holes on site to fasten the components together.

-

- Use of modular buildings was more advantageous in many respects than construction

on site of temporary structures. The main objection was the procurement cost

which was substantially higher than a wooden structure built on the same site.

However, the savings realized by purchasing relocatable structures and from

cost reduction in erection time tended to offset high initial costs.

- [88]

- page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents