- Chapter V:

The Bases

The port of Saigon and, to a lesser extent, the port of Cam Ranh Bay

were the only harbors in South Vietnam capable of docking deep-draft

oceangoing vessels before the force buildup in early 1965. There were

shallow-draft port facilities at Nha Trang, Qui Nhon, and Da Nang, and

there were numerous beaches along the coast over which cargo could be

landed from ships lying offshore. But in 1965 only one berth in the old

port of Saigon was permanently allotted to American forces, although from

two to ten were used at various times. In January 1966 three berths were

permanently assigned for United States military use in Saigon. Cam Ranh

Bay had at that time only one deep-draft pier in operation which was

insufficient for existing and projected cargo handling requirements.

From Washington a close watch was being kept on the operation of

Vietnamese ports throughout 1965 and 1966. Ninety percent of all military

supplies and equipment were destined to arrive in Vietnam by deep-draft

vessels, and millions of tons of foodstuffs and nation-building equipment

imported by the U.S. Agency for International Development and the

Vietnamese government were at the same time competing for berth space at

the port of Saigon. Until an effective Pacific theater movement agency was

in operation to balance port reception capability with inbound shipping

and until limits were placed on out-of-country cargo shippers, a

tremendous backlog of vessels could be expected in Vietnamese waters or in

nearby port facilities. At one time over 100 deep-draft vessels were

awaiting discharge in Vietnamese waters or were in holding areas at

Okinawa in the Ryukyus or Subic Bay in the Philippines. Many ships loaded

with supplies had to wait several months for berthing and off-loading.

The Army lacked the shallow-draft shipping necessary to take advantage

of shallow port facilities, but this was offset somewhat by landing cargo

across undeveloped beaches; deep-draft vessels were unloaded into Army and

Navy landing craft and civilian barges. Although supplies could be landed

this way, it was not sufficiently

[50]

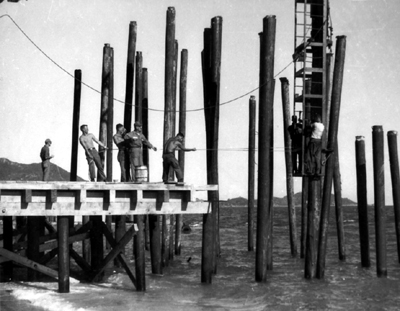

EARLY CONSTRUCTION at Cam Ranh Bay by the 497th Port Construction Company.

rapid and would certainly not work as supplies were increased. There

never really were enough lighters or barges.

The 1st Logistical Command Engineer Section was responsible for initial

construction planning for Army requirements in Vietnam, including the

development of port facilities. This small section began the initial

development of ports. Upon the arrival of the 18th Engineer Brigade and

with the organization of a USARV Engineer Section, this responsibility was

transferred to a new headquarters. Planning for the over-all development

of ports within Vietnam became the responsibility of the Assistant Chief

of Staff for Logistics, the MACV J-4.

Later in the summer of 1965, the USARV Engineer Section made studies of

required construction to refine the original plans. The only organized

Army port construction company, the 497th, arrived at Cam Ranh Bay late

that summer from Fort Belvoir, Virginia, to assist in the port

construction program. The 497th helped develop requirements and plans for

both long- and short-range port

[51]

facilities throughout Vietnam, exclusive of the I Corps area, whose

development remained with the Navy.

The plan was to develop Saigon, Da Nang, and Cam Ranh Bay into major

logistical bases and Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Phan Rang, Chu Lai, Phu Bai, and

Vung Tau into minor support bases. Because of the tactical and

geographical isolation of these ports, all supplies had to come by sea.

Port development involved more than the construction of additional piers.

Barge off loading facilities, ramps for landing craft, and petroleum

unloading facilities were all required.

To begin the port construction projects, a fleet of dredges was

assembled under the flag of the Navy's Officer In Charge of Construction.

The hydraulic dredge is without question the most useful piece of

equipment afloat for harbor and channel projects, reclamation and

landfill, and for providing the huge stockpiles of sand necessary for

other construction projects. In 1966 the dredge fleet included two

side-casting and three hopper dredges, the Davison and the Hyde from

the Army Corps of Engineers civil works fleet, and eighteen pipeline

cutterhead dredges. During the period November 1965 through May 1970,

hydraulic dredges excavated 64.8 million cubic meters of canal, entrance

channel, and river bottom material.

The scope of work, availability of funds, hydrographic surveys, soils

explorations, length of maintenance and overhaul periods, and desired

completion dates are as in the planning and executings of dredging

operations as in any other engineering project; but familiar problems were

compounded by a few others in Vietnam. For example, the monsoon season

interrupted earthwork on land reclamation projects; civilian crews

operating dredges had to be protected against enemy attack; safety

measures were imperative for dredging in areas where the marine bottom was

peppered with live explosives; and the extremely long supply line was

encumbered with faulty requisition transmission, frustrating concepts, and

an extreme shortage of needed replacement parts. Added to this was an

ever-changing tactical situation which would not respect previously

established readiness dates or work schedules.

Site acquisition was the first step in hydraulic fill operations.

Maintenance dredging projects usually encountered little opposition, since

both the military and civilians considered land reclamation beneficial.

However, when improved land was required for a project, time-consuming

negotiations followed. Requests for hydraulic fill projects had to be

forwarded by the military to the Interior Ministerial Real Estate

Committee, Ministry of Defense, Government of Vietnam. If approved, IMREC

directed the appro-

[52]

priate province chief to form a committee to evaluate real-estate costs

and to determine what homes, graves, facilities, or other improvements

would require relocation and to whom compensation would be paid. After the

site was acquired, actual work could begin. To illustrate how dredging

operations progressed in Vietnam, we can consider one project-at Dong Tam

in IV Corps.

Dong Tam, a marshy area lying along the My Tho River, eight kilometers

west of the town of My Tho and sixty-five kilometers southwest of Saigon,

was selected as the site for a joint Army-Navy military complex. To

develop the location into a base required excavating a rice paddy for

development into a turning basin and dredging an entrance channel into the

basin from the My Tho River. The over-all plan also called for dredging

sand from the river, creating a landfill of one square mile and providing

a stockpile for airfield, concrete, and road construction projects in the

surrounding area. The 16-inch pipeline cutterhead, Cho Gao, first of five

dredges assigned, started work on 4 August 1966. The basin and channel had

a higher priority than the sand stockpile and were completed in April

1967. The shortage of sand at Dong Tam persisted.

Dredging at Dong Tam was not without combat losses. First, the Jamaica

Bay, a 30-inch pipeline cutterhead dredge, was sunk by sappers on 9

January 1967. Two American crew members were drowned during the incident.

Subsequently, the dredge was salvaged, but while under tow off the port of

Vung Tau, she encountered heavy seas and sank. Attempts to raise her were

unsuccessful and the dredge now lies on the bottom of the South China Sea

off the coast of South Vietnam. Fortunately her sister dredge, the New

Jersey, was also in the country and available as a replacement.

The Thu Bon 1, a 12-inch pipeline cutterhead dredge, was sunk by

sappers on 28 July 1968 while working in the entrance channel. Following

salvage, a survey team estimated that repair costs would reach at least 75

percent of the purchase price; therefore, the decision was made to scrap

the dredge for parts. She was replaced by a similar 12-inch dredge, the Thu

Bon 11. Thirteen months later, on 22 September 1969, the U.S.

Navy-owned 27-inch pipeline cutterhead Sandpumper sucker up live

ordnance from the bottom of the My Tho River and sank following detonation

of the explosive. For a period of four months, attempts were made to raise

her but, as in the case of the Thu Bon I, a cost survey revealed

that salvage and repair were not economically feasible. A disposition

board recommended that the dredge be stricken from the register of U.S.

Navy vessels and turned over to military authorities for disposal. The

[53]

Sandpumper now rests in the My Tho River, posing no immediate threat

to navigation and awaiting her ultimate fate.

Finally, on 22 November 1969, sappers sank the 30-inch pipeline

cutterhead New Jersey. Harbor Clearance Unit One, a U.S. Navy team

from the Subic Bay Naval Base, raised her on 30 December. Taken to

Singapore in January 1970, she underwent overhaul and repairs in the

Keppel Yards. In May 1970 she was towed back to Vietnam, refitted with the

gear that had not been taken to Singapore, and put back in operation

performing maintenance dredging at Qui Nhon.

An outstanding contribution in expediting the port construction program

was made by using DeLong Floating Piers. These patented products of the

DeLong Corporation are sectional and can be fabricated outside of the

theater of operations in a variety of sizes and configurations, towed to a

site, and quickly emplaced. These piers made it possible to develop

additional deep-draft ports and berths at Qui Nhon, Vung Tau, Cam Ranh

Bay, Vung Ro, and Da Nang in record time.

The first DeLong pier with all its equipment and spare parts was towed

to Cam Ranh Bay from the east coast of the United

A DELONG PIER under construction at the Cam Ranh port facility.

[54]

States in a trip that took about two months. The men of the 497th Port

Construction Company, who were to place the pier, were inexperienced in

the construction of DeLongs and had to learn on the job. Advice and

technical assistance were provided by representatives of the manufacturer.

The first pier was essentially a 90x300-foot barge supported by eighteen

tubular steel caissons six feet in diameter and fifty feet long. The

additional caisson sections were joined end to end to provide the required

length. Collars attached to the pier caissons were driven into the harbor

bottom, and pneumatic jacks, which were a part of the collars, were then

used to jack the barge up on its legs to a usable height.

Before placing the pier, no test piles could be driven or test bores

taken because the equipment was lacking. Test bore data was available for

the adjacent pier, but the depth of refusal for the caissons could not be

accurately predicted. Because of a mud layer beneath the sand bottom of

the bay, three lengths of caisson 150 feet long were required at each

location. Although two sections could be joined before erection, the third

had to be welded on in place, a process that required twenty days. The

first DeLong pier, completed in mid-December 1965, doubled the capacity of

the Cam Ranh Bay port. This pier required forty-five days for construction

by sixteen men. Engineers estimated that a timber-pile pier would have

required at least six months' work by a construction platoon of forty men,

plus supporting equipment and operators, as well as a large number of hard

to get timber piles and construction timber. It was demonstrated that

significant savings in time and material could be had with the DeLong pier

compared to an equivalent timber-pile pier.

The two existing piers for deep-draft vessels still lacked in-transit

storage areas, so a sheet-pile bulkhead was constructed between the

causeways to each pier. The area behind the bulkhead was filled in using a

30-inch pipeline dredge and 96,000 cubic yards of material. The surface

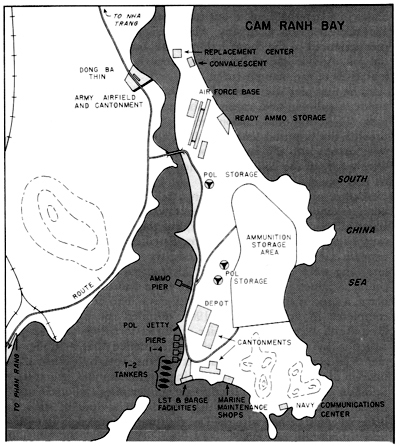

was then stabilized to provide a large cargo-handling area. (Map 5)

Work started on the third general cargo pier at Cam Ranh Bay in May

1966. This was a two-barge DeLong pier ninety feet wide by six hundred

feet long. It was installed by the DeLong Corporation, which was under

contract to the Army to install all the additional DeLong piers used in

Vietnam, with engineer units providing connecting causeways, abutments,

roads, and hardstands.

In September 1965, large-scale landing ship, tank (LST), operations

began. LST's transported supplies from Saigon, Cam Ranh Bay, and Okinawa

to the shallow ports of Qui Nhon, Vung Tau,

[55]

MAP 5

CAM RANH BAY

and Nha Trang. Consequently, the first job for the port construction

company was to increase the traffic-handling capacity at these sites.

Sand on many Vietnamese beaches becomes almost impassable with heavy use

and severely limits the loads that can be transported across the beach.

Many methods of stabilizing sand were tried unsuccessfully, and wave

action over the beaches washed away most expedients. However, late in

1965, large coral beds were found offshore at Cam Ranh Bay; these deposits

were then blasted and excavated with draglines. The coral was crushed and

hauled to the landing sites. The foreshore area between high and low tide

marks was excavated to eighteen inches, and the crushed coral was placed

[56]

FIRST DELONG in use at Cam Ranh.

in layers and compacted with rollers, then the beach was graded to its

original alignment. This process gave satisfactory results that lasted for

several months with only minor repairs.

At Cam Ranh Bay the first expeditionary airfield was under construction

by Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen, and the first jet fighter aircraft were

scheduled to arrive on 1 November 1965. However, the fuel supply available

was inadequate, so in early October work started on a 400-foot timber fuel

jetty extending out to the five and a half fathom line. The floating

pile-driving equipment of the port construction company was used to

construct the jetty, and on 1 November fuel was being pumped from a tanker

to the Cam Ranh Bay Air Base ten miles away. But marine wood borers, which

are prevalent in Vietnamese waters, caused a goodly amount of damage to

the jetty's untreated timbers within a very short time. Treated timbers

were not available for bracing of either the POL jetty or the wharf; and

lateral and longitudinal bracing had to be replaced quite often.

With the addition of the third and fourth DeLong piers, and more than

3,000 linear feet of bulkhead, the port facility formed a major part of

the logistical area at Cam Ranh Bay, which became one of the largest in

the Republic of Vietnam.

Soon after arriving in Cam Ranh Bay, the 1st Platoon of the 497th

Engineer Company went to Qui Nhon where with elements of the 84th Engineer

Battalion a considerable effort was being made to increase the capacity of

port facilities. A "Navy cube" floating

[57]

pier, 42 feet wide by 192 feet long, was built and connected to the

shore with a 200-foot rock-filled causeway in February 1966. These cube

piers consisting of 5x7x7-foot cubes of steel fastened together with angle

irons and cables were used extensively in Vietnam. They could be towed for

short distances and emplaced where needed, requiring very little on-site

construction time.

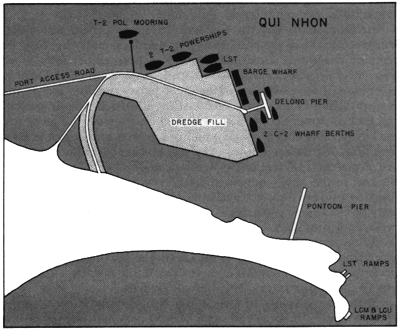

Inasmuch as Qui Nhon was a shallow-draft port, ramps for landing craft

were needed. However, no suitable land was available. The first step,

therefore, was the extension of the Qui Nhon Peninsula with approximately

45,000 cubic yards of fill to create a usable area measuring 620 feet by

360 feet. A sheet-pile cofferdam was built to exclude water from the work

site, and select fill was placed and faced with riprap, or a lose stone

foundation, on a slope of five to one. This extension to the peninsula

provided an excellent place for LCU's (landing craft, utility) and LCM's

(landing craft, mechanized) to unload and also increased the in-transit

storage area by more than 100 percent. (Map 6)

In February 1966 Qui Nhon was changed from a support area to a

logistical base, which required increased storage capacity. Ton-

QUI NHON

[58]

nage requirements were calculated, and the design for the port was

developed. Phase I included eight barge unloading points, four deep-draft

berths provided by DeLong piers, and two permanent LST ramps. In June 1966

the 937th Engineer Group began building a four-lane port access road 1.5

miles across the bay to bypass the congested city of Qui Nhon. The subbase

of the access road was hydraulic fill. The approach channel, some two

miles in length, and the turning basin were dredged. A total of 4,000,000

cubic yards of material was moved. A submarine pipeline for the transfer

of petroleum from tankers to tank farms was installed. Two 4-inch lines

near the landing craft ramps and one 4-inch line on the seaward side of

Qui Nhon were also put in but were accessible only to small tankers. For

stabilizing the tankers while unloading, a system of anchorage and

breasting dolphins was rigged at the sea end of the pipelines.

With the increased movement of troops into the Saigon area, .the

deep-draft facilities there proved completely inadequate. However, a plan

was already under way to construct a new port on the Saigon River upstream

from the city. The location was chosen by Captain Maury Werth, U.S. Navy,

who was a special assistant to the MACV J-4. This site, called Newport,

was in a sparsely populated area adjacent to a main highway connecting

Saigon with the newly developing Long Binh area some twenty miles from

Saigon. This massive project financed by the Army was constructed by

RMK-BRJ.

To meet the immediate need for additional port facilities in the Saigon

area, the 18th Engineer Brigade built six cargo barge unloading points

near the Long Binh Depot. The ammunition unloading points were constructed

on the Dong Nai River at Cogido, and two piers were constructed for

docking.

The 536th Port Construction Detachment, consisting of a construction

platoon and construction support elements, operated in Vung Tau during the

spring of 1966. This detachment developed temporary LST facilities,

timber-pile piers, sheet-pile bulkheads, and DeLong pier abutments.

Improvements in the flow of cargo not only had a military impact but

also aided the Vietnamese people, since a steady flow of consumer goods

helped to combat the inflation which threatened to ruin the Vietnamese

economy. To a very great extent, the success in providing logistical

support to American forces in South Vietnam was a direct result of port

expansion.

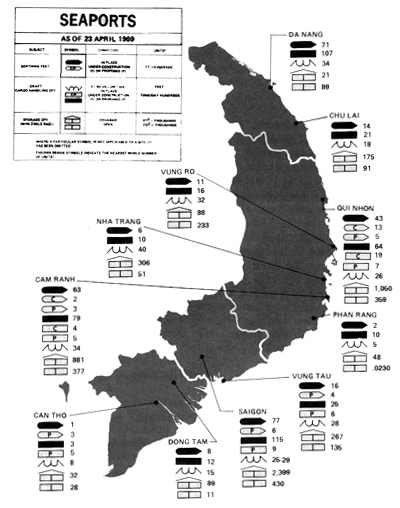

The capacity of permanent port facilities in South Vietnam increased

many times over, with the construction of new facilities at Newport,

Saigon, Vung Tau, Cam Ranh Bay, Qui Nhon, Da

[59]

Nang, and other installations. Port development throughout the coastal

region of South Vietnam gave the republic permanent access to the sea,

thus promoting development of a stabilized economy and the emergence of

Vietnam as an Asian trading center. (Map 7)

As the building of improved ports and docking facilities continued, a

network of air bases was under construction which further

[60]

absorbed the engineers' attention. The differences in high-performance

aircraft used by the French and Vietnamese, as opposed to the American

military machine, forecasted the development of jet air bases in Vietnam

that would be an engineering undertaking of enormous magnitude.

When Navy Mobile Construction Battalion Ten landed with the Fourth

Marine Regimental Landing Team at Chu Lai to construct an all-weather

expeditionary airfield, it found the site covered with shifting wind-blown

dunes of quartzite sand. The use of pneumatic-tired equipment was severely

restricted, and the amount of earthwork required to level the site

presented a serious problem, since speed was essential.

At Chu Lai, Navy Mobile Construction Battalion Ten was able to provide a

continuously operational jet airfield while conducting extensive

experimental work for the future use of AM-2 aluminum matting (the

successor to World War II pierced steel planking) runway designs. The

original operational strip, 3,500 feet long, was laid on a laterite base

10 inches thick. Confined to a small beachhead area, the Seabees and

marines had little choice of material, and the available laterite proved

to be of a very poor quality. Although it was originally planned to use

plastic membrane seal between the laterite and the matting, the plastic

material was not available in time for the first section of runway. This

3,500-foot section, equipped with arresting gear, was laid without a seal

under it. It was started on 7 May 1965 and completed in twenty-one days.

By 3 July the Seabees and marines had constructed an entire 8,000foot

runway, an 8,000x36-foot taxiway, and an operational parking apron of

28,400 square yards. This airfield, however, eventually experienced base

failure, and the laterite was replaced with soil cement.

The second major aluminum mat airfield in Vietnam, constructed by

RMK-BRJ, was at the Air Force base at Cam Ranh Bay. A runway 10,000 feet

long by 102 feet wide was constructed on an all-sand subgrade. Because of

the experience at Chu Lai, particular attention was paid to the base under

the matting. Extensive soil stabilization work, beginning on 22 August

1965, included flooding the sand with sea water and rolling to stabilize

it so that the sand could support earthmoving and compaction equipment.

Following compaction and grading, the base was sealed with bituminous

material. Laying of matting began late in September, and the runway was

completed on 16 October. With completion of the runway, a parallel

taxiway, high-speed turnoffs, and 60,000 square yards of operational

apron, all in AM-2 plank, the scheduled operational date of 1 November was

met.

[61]

Another AM-2 runway, identical in size to the one at Cam Ranh, was

constructed at Phan Rang. It was started in September 1965 by the 62d

Engineer Construction Battalion. Once again, the quality of the base was

first improved. At this field a graded fill material was placed beneath

the matting, and for the first time flexible plastic membrane was used as

a seal. The first aircraft landed on the runway on 20 February 1966. The

entire 10,000x102 foot runway was completed on 15 March, along with

sufficient taxiways and aprons to provide an operational jet airfield.

Later base failures, however, caused extensive reworking on the original

airfield.

Believing that the Navy contractor would be unable to meet occupancy

dates for some of their projects in Vietnam, the Air Force in February

1966 requested authority from the Secretary of Defense to make a separate

contract with a U.S. firm for construction of an air base. Air Force

officers detailed the scope of work but did not identify the site at

meetings with potential contractors. The agreement they proposed to use

was a "turnkey" contract whereby the contractor assumed

responsibility for shipping and logistic requirements as well as for

design and construction.

General Westmoreland and Admiral Sharp both opposed the introduction of

another cost reimbursable construction contractor into Vietnam, arguing

first that the air base was unnecessary and second that the proposed

turnkey arrangement would bring one more construction organization into

the country to compete for port facilities, storage, transportation, and

other logistic support. The Secretary of the Navy supported General

Westmoreland by pointing out to the Secretary of Defense that any scheme

for increasing contract construction in Vietnam should take advantage of

the existing capability of RMK-BRJ. On 12 March 1966 General Westmoreland

reiterated his reasons for nonconcurrence with the Air Force proposal, and

the following day Admiral Sharp endorsed General Westmoreland's position.

On 21 April, after being directed to reconsider the situation by the

joint Chiefs, General Westmoreland concluded that an additional airfield

could be used. The preferred site was at Hue, but because this site was

unavailable he recommended to Admiral Sharp that work start at Tuy Hoa.

On 27 April the Joint Chiefs of Staff consented to agree on Tuy Hoa,

only if the Hue site was completely out of the question. They agreed to

help surmount State Department objections to the Hue project but, in the

interests of speed, urged that preliminary work be pushed at both

locations. Responding to this message on 6 May, General Westmoreland

mentioned Chu Lai as an acceptable alter-

[62]

native to Hue and concurred in proceeding with the Tuy Hoa site using

the turnkey concept, as well as with a parallel runway at Chu Lai using

the Navy's contractor.

On 7 May 1966 Admiral Sharp approved the Tuy Hoa proposal but imposed

certain conditions. The Air Force's turnkey contractor would be

responsible for building the complete Tuy Hoa complex -air base, port, and

breakwaters-as well as for relocating roads and trackage. He would

mobilize his own equipment, manpower, materials, and dredges, using only

such local resources as were surplus to other service requirements. He

would also be responsible for his own sea lift, unloading, beaching, and

barging. In late May the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave the project their

blessing, and on the 27th of that month the Deputy Secretary of Defense

authorized the Air Force to negotiate a turnkey contract for the Tuy Hoa

air base.

At Tuy Hoa, an 8-inch soil cement base was planned under the AM-2

aluminum mat. The airfield facilities included a 150x9,000foot runway, a

parallel taxiway 75 feet wide, and some 165,000 square yards of apron,

with lighting, markers, and barriers. A control tower, operations

buildings, and a communication facility were included. At first, a mobile

tower and portable navigational aids were to be used. Fuel was handled

through a 300,000-gallon "bladder system" until welded steel

tanks were ready.

In all, five major jet air bases were constructed in Vietnam to

supplement the three already in existence, and over 100 widely dispersed

fields were built for intratheater transport aircraft. The major air bases

afforded the necessary facilities for tactical aircraft and aircraft

arriving from outside Vietnam, while the smaller fields allowed dispersal

of logistics in support of forces operating in the field. The newly

developed aluminum matting and older steel planking allowed construction

at the most remote sites and permitted air delivery by heavier fixed-wing

aircraft.

By mid-1966 the plan was to have every point in South Vietnam within

twenty-five kilometers of an airfield. (See Map 8.) The few

existing outlying airfields had been constructed mainly by the French.

These strips were paved with a surface treatment from one half to one inch

thick and could not withstand the heavy volume of traffic required during

tactical operations. In some of these operations up to 100 tons of

supplies and 200 aircraft sorties were required daily.

The very nature of the war scattered small troop detachments to outlying

locations. These detachments were supplied by air, primarily by CV-2

Caribou aircraft which were capable of landing on 1,000-foot hastily

constructed airfields. Most of the early forward airfields were

constructed with expedient surfacing materials such as

[63]

TWO CARIBOUS debark troops on unimproved runway.

laterite and crushed rock, which later proved to be inadequate. These

surfaces had been used because a suitable matting was unavailable at the

time of construction. M8A1 matting later was used extensively for forward

airfields, although it required considerable maintenance when used by

heavily loaded aircraft.

Forward airfield construction was rough and crude. Yet, experience

indicated that the construction of each airfield should be preceded by as

detailed a reconnaissance as time and circumstances would permit. In

almost all instances the reconnaissance was made by helicopter. Landing

permitted cone penetrometer soil-bearing tests and clearing and grading

estimates. Time on the ground was usually limited to a few minutes because

of possible enemy attack. With the ground survey completed, aircraft

instruments were used to determine the runway azimuth and to estimate

runway length.

Division operational plans and areas were often based on the

availability of an airstrip that could be used by supporting fixed wing aircraft and which was at or near the tactical operations area. Completion

time was critical. Consequently, the reconnaissance was extremely

important and accurate work estimates were essential.

Heliports varied in size from the brigade base camps of airmobile

divisions to the isolated rearming and refueling facilities scattered

about which have become common to the airmobile con-

[64]

cept. While little preparation was required for a one-time landing zone

in the forward areas, both the west and dry seasons in Vietnam posed

significant problems in construction and maintenance of areas with a high

density of helicopter traffic.

As with any piece of equipment, helicopter maintenance problems received

command interest only after the abrasive effect of heavy dust was

realized. Dust suppression was an obvious necessity for the safety of

pilots during takeoffs and landings, and the damage dust caused to turbine

blades was as effective as combat action, if not as dramatic, in downing

aircraft. The use of matting or planking was effective in providing dust

control, but unfortunately it was seldom feasible at hasty facilities

constructed for helicopter operations. Periodic ground spraying with

.diesel fuel provided a relatively easy means of dust surpression for

short periods of time, and usually some type of a trailer- or

truck-mounted distributor could be manufactured for continued use by the

using unit. Soil binders were effective for several weeks but were easily

disturbed by vehicular traffic on the pad and could not withstand the

monsoon season. The construction of a hardstand of asphaltic compounds or

concrete offered a permanent solution and was considerably more economical

in the long run than various types of portable matting.

The monsoon season also created many problems for heliports, which were

often located in flat low-lying areas characterized by poor drainage.

Considerable attention was required to ensure that all existing facilities

would be usable, even after the very heavy monsoon rains. Both erosion and

standing ,water had to be controlled or eliminated, and control of

vehicular traffic through the heliport had to be regulated. Vehicles

constituted a source of erosion and a safety hazard to approaching and

departing aircraft, yet they were normally essential for aircraft

maintenance and reprovisioning.

Much of the construction required to support aviation units was not

included in early planning. Each aircraft in Vietnam eventually required a

protective revetment. One of highest priorities in Vietnam , during 1968

was the construction of protective structures for tactical aircraft. Known

as the Hardened Shelter Program, the task of erecting these structures was

assigned to Air Force Prime BEEF teams (base emergency engineering

forces). The shelters eventually found most efficient in terms of unit

cost (for fighter aircraft) were 72 feet long, 48 feet wide, and 24 feet

high corrugated steel arch structures, which were covered with concrete

for protection against rocket and mortar fire.

In the development of protective structures, particularly for

helicopters, various designs were tested with the primary purpose of using

materials indigenous to or readily obtainable in Southeast

[65]

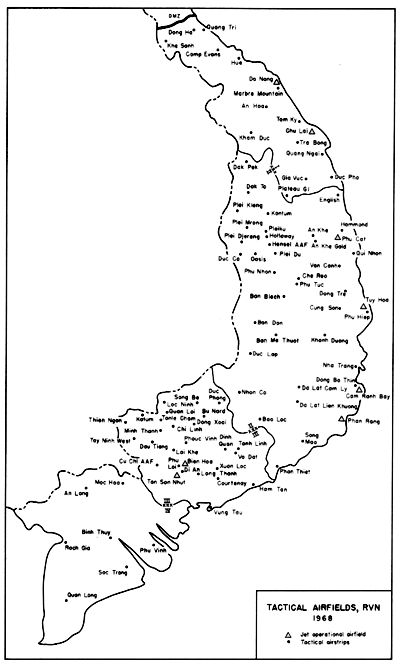

MAP 8

TACTICAL AIRFIELDS, RVN 1968

[66]

Asia and of utilizing the manpower, skills, and equipment usually

available to military field commanders. Vertical, sloping, and cantilever

revetment walls were evaluated for their ability to protect against

conventional weapons attacks. Construction procedures, requirements, and

costs were studied, and basic weapons effects data pertinent to future

protective structures were obtained.

Revetments did not provide complete protection for aircraft, but they

did stop or deflect fragments. Only a cocoon-type enclosure, which in

itself was able to resist both blast pressure and fragments, would

completely protect an aircraft; but the cost of these structures, as well

as the space occupied and the operational limitations imposed, made

cocoons impractical as a solution for rotary-wing aircraft. Since some

protection could be achieved with revetments alone, they were generally

used. Protection against blast pressure, which might cause detonation of

fuel and armament, had to be achieved by adequate spacing of aircraft.

Considerable efforts were made to determine the most effective revetment.

Earth-filled timber bins, cement-stabilized earth blocks, plain or

cement-stabilized sandbags, sulphur and fiberglass coated cement blocks,

soil-cement, and earth-filled fiberglass resin cylinders were the most

suitable materials for revetment construction. Corrugated asbestos

material with earth fill was effective against small arms fire; however,

this brittle material was easily damaged by heavy weapons fire. Steel

sheet piling without earth fill proved to be very ineffective in stopping

small arms fire and fragments, but it had other drawbacks.

Seldom did economy or available construction materials permit much

latitude in the selection of revetment types; the commander usually had to

base his decision on erection time, equipment requirements, and the degree

of protection desired. By the nature of their mission, aviation units have

to relocate frequently, and each move required additional revetment

construction. In Vietnam experience showed that approximately one-third of

the units relocated annually. This mobility necessitated the use of

prefabricated revetments which could easily be assembled, disassembled,

and moved with the redeploying aviation units.

Use of M8A1 or other types of matting was considered justified to

protect the enormously expensive aircraft, but investigation revealed that

adequate protection was available with lower cost materials-particularly

for rotary-wing aircraft. Corrugated sheet metal on 2 X 4 A-frames filled

with earth proved to be effective, easy to construct, and relatively

economical.

The use of precast concrete revetments was initiated in 1970. By this

time precast yards were already manufacturing bridge decking, and the

yards were easily converted to revetment fabrication.

[67]

Tests indicated these revetments were particularly effective and that

they offered the advantage of long life and portability. From late 1970

on, the precast concrete revetment was adopted for exclusive use.

With construction in .full swing, the size of bases continued to

increase. The U.S. Navy complex at Da Nang in I Corps supported a powerful

combined force. As of early 1968 more than two-thirds of the Navy's

strength in Vietnam, or 22,000 men, were in I Corps, and the majority of

them were in Da Nang. The Air Force had most of its 7,000 men in I Corps

also stationed there. The port supplied the logistic support for the 1st

and 3d Marine Divisions and several Marine support agencies. In all there

were 81,000 marines being supported from the Da Nang complex in early

1968. As Army units moved north into I Corps in support of U.S., Korean,

and Vietnamese forces, there would be seventy-three infantry battalions

operating in these five provinces. The major: facilities at Da Nang

included:

1. The deepwater port.

2. The Naval Support Facility depot.

3. Jet airfields at Da Nang and Chu Lai.

4. A C-130 airfield at Hue.

5. Shallow LST ports at Chu Lai and Hue.

In late 1966 the Qui Nhon complex in II Corps supported combat

operations of 15,100 combat troops (including 6,300 ROK) and 25,000 combat

support troops (including 10,800 ROK) as well as service support elements

numbering 22,100. Combat figures included some 550 Navy personnel engaged

in coastal patrol and harbor defense. These men were part of the MARKET

TIME operations. Cantonments were arranged so that all functional elements

(combat, combat support and service) were grouped together. Major

logistical and support facilities included:

1. Deepwater port with four berths at Qui Nhon.

2. Depot at Qui Nhon.

3. Jet airfields at Phu Cat and Tuy Hoa.

4. Five C-130 capable airfields at Kontum, Pleiku, Che Reo, Qui Nhon,

and An Khe.

5. MARKET TIME facilities at Qui Nhon.

In late 1966 the Cam Ranh Bay complex in II Corps supported the

operations of 8,000 combat troops (including 2;400 ROK) and 11,100 combat

support troops (including 2,000 ROK), as well as 17,000 service support

troops on a direct basis, and in addition provided general support backup

for the entire theater. These

[68]

figures included 2,450 naval personnel supporting MARKET TIME, harbor

defense, and the Naval Air Facility. The major logistical and support

facilities included:

1. Deepwater port with ten berths at Cam Ranh.

2. Depot at Cam Ranh.

3. LST ports at Nha Trang, Phan Rang and Tuy Hoa.

4. Jet airfields at Cam Ranh Bay and Phan Rang.

5. Six other airstrips of which five were C-130 capable (Ninh Hoa: C-123

only).

6. MARKET TIME facilities.

In late 1966 the Saigon complex for III and IV Corps Tactical Zones

supported 39,700 combat troops (1,400 allies) and 18,300 (5,200 allies)

combat support troops, as well as 42,800 service support troops.

Operations included MARKET TIME and GAME WARDEN. The major logistical and

support facilities included:

1. Deepwater ports at Saigon (including Newport).

2. Depot at Saigon.

3. LST ports at Vung Tau and Can Tho.

4. Jet airfields at Tan Son Nhut and Bien Hoa.

5. Eight other airstrips of which five were C-130 capable.

6. MARKET TIME and GAME WARDEN facilities.

With the location of each major port of entry established on the concept

of a series of logistical islands, each with easy access to the sea, the

construction of more extensive base complexes proceeded apace. With no

connecting roads and reliance on sea transportation for bulk supply, each

island was a self-supporting unit capable of sustaining combat units in

its immediate area of operations.

Until 1968 the I Corps Tactical Zone was under Navy and Marine Corps

jurisdiction for the most part, with only a small Army contingent on hand.

In the other three tactical zones in South Vietnam, the area support

commands in Saigon, Qui Nhon, and Cam Ranh Bay operated under Army

command, the Navy maintaining smaller facilities for the support of naval

combat and patrol operations but obtaining items of common supply from

Army stocks. After the spring of 1968 the Army moved in force into the I

Corps Tactical Zone, basing its support operations at the already

functioning base at Da Nang.

As the troop commitment to Vietnam increased, the numbers of individual

supply depots of the logistical island type multiplied; each of the area

commands became the hub of a network of smaller depots, and the demand for

construction at their lesser "subarea"

[69]

commands progressed accordingly. From a mail-order supply operation

supporting some 25,000 American troops in 1965, the system expanded into a

complicated and functioning, though sometimes less than efficient, machine

supporting over a half million troops in three years' time.

[70]

page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents