CHAPTER V

Model for the Future

No conflict in recent history has divided the American nation as much as the war in Vietnam. This study does not attempt to analyze the controversies surrounding the war or the psychological factors bearing on it or questions of U.S. foreign policy. However, since military planners must develop doctrine that can be applied in future military contingencies, lessons learned in Vietnam can be helpful. Some of these lessons concern theory and doctrine on effective command and control structures.

Military doctrine presupposes political decisions at the highest national level, which take into account the objectives and available means of military action. The planners use doctrine as a blueprint and apply it to the particular set of circumstances. These circumstances include the status of political relations between the United States and the country receiving assistance, the stability and, effectiveness of the country's government, and the estimated magnitude, intensity, and duration of a U.S. military commitment. Obviously, these factors will influence the type of command organization selected to control U.S. Military operations.

Command and control arrangements must meet other, more specific criteria. From the U.S. viewpoint, command and control must be comprehensive enough to exercise control over all military forces assigned by U.S. national authorities; flexible enough to respond to changes in the situation, such as a demand for specific control of air or naval operations in support of ground forces; and able to provide national authorities with timely, accurate, and complete reports. The command and control structure must also be capable of close co-operation with and constructive support of indigenous and allied military forces, paramilitary organizations, and other agencies of the host country.

In applying lessons learned in Vietnam to a hypothetical future conflict, the commitment of substantial contingents of U.S., allied, and indigenous forces for an extended period of time will be assumed. Further assumptions will be that U.S. objectives include an early conclusion of hostilities on terms favorable to the host government, that the conflict is limited to predetermined geographical and political areas, and that indigenous forces are to be strengthened,

[85]

thus enabling them to assume responsibility for internal security. This example is not to be interpreted as a replica of the conflict in Indochina, nor do the following suggestions imply criticism of the command and control arrangements of the war in Vietnam.

The doctrine for command and control in this hypothetical case will be based on the premise that the conflict is classified as a single war, not one divided into separate geographical zones and by individual service missions. Another prerequisite will be unity of command, to ensure both tight control of the over-all U.S. effort by American political authorities and effectiveness of military operations and advisory activities. The command structure should encourage improvements in the operational capabilities of the indigenous forces and promote cooperation with them. Finally, the command and control arrangements should be sufficiently flexible to adjust to changes during the course of the war.

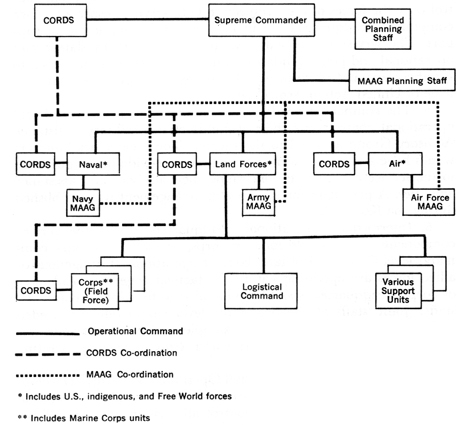

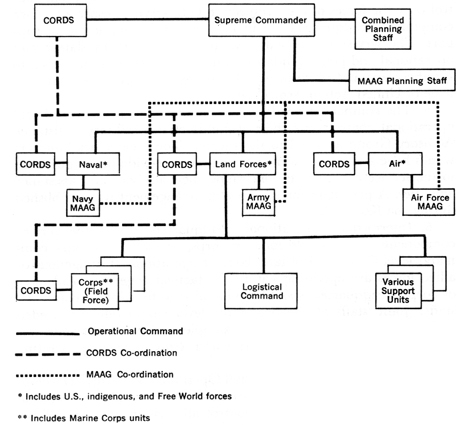

Given these premises, the optimum command and control structure would include the following recommendations.

1. A unified theater command directly under the joint Chiefs of Staff should be established to conduct military operations. Other unified or specified commands may be assigned supporting missions depending on the type of conflict. The theater commander should have powers comparable to those exercised by supreme commanders in Europe and the Pacific during World War II.

2. Initially, the unified command (theater headquarters) should exercise operational control over forces provided by the host government. This command should also have operational control over military forces furnished by allied nations. The prototype of this arrangement is found in the Korean War. As an alternative, the unified command might only exercise control of U.S. and other outside forces committed to the theater. The degree of control over indigenous forces could be modified according to political circumstances but should be great enough to ensure prompt development of the ability of these forces to undertake unilateral operations successfully.

3. Combined operational and planning staffs should be established at the theater level and at major subordinate operating commands. A combined planning group, headed by an officer of the host government and staffed by representatives of the governments providing forces in the theater, is considered the best means of bringing the over-all effort together. An example of a combined staff is the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force in World War II.

[86]

4. Component headquarters, subordinate to the unified (theater) headquarters, should exercise both command and operational control over the forces of their respective U.S. services, especially since component headquarters are in fact responsible for logistical support. The service component headquarters should translate broad operational and policy guidance from the theater headquarters into specific plans and programs. This procedure follows the joint doctrine of United Action Armed Forces.

5. The component headquarters should exercise command and operational control over their elements of the Military Assistance Advisory Group assigned to the theater. The theater headquarters would have a separate, joint staff section to provide policy guidance to the service components concerning their advisory and assistance activities. A precedent for this type of arrangement was established during the Korean War.

6. Intermediate operational headquarters under the service components, such as field force or corps, provide a necessary command level for control of land combat operations. If indigenous or allied forces are operating within the tactical zone of a field force or corps, headquarters should be modified to function as combined staffs. Joint staffs at the field force level would only be needed under special circumstances, for example, if the combat zone was geographically isolated or if Marine and Army units were operating in the same area.

7. An organization like the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS) in Vietnam should be established as soon as possible. It should directly control all civilian advisory efforts, especially those of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Joint United States Public Affairs Office. Without such control, civil affairs and counterinsurgency and pacification operations cannot be adequately co-ordinated. The functions of a CORDS-type organization could best be controlled through an arrangement similar to the one specified for Military Assistance Advisory Group activities.

8. Operational control of combat support and combat service support units needed on a day-to-day basis should be exercised by the intermediate field force or corps headquarters. Control of all other combat support and combat service support units should be retained by the Army component headquarters on the single-manager principle. This arrangement should apply specifically to Army air, engineer, signal, and medical units.

9. For common items of supply and services, logistical support should be provided according to a single-manager principle agreed upon by the four services. (Chart 11)

[87]

CHART 11-PROPOSED COMMAND AND CONTROL ARRANGEMENTS

In Vietnam the doctrine of command and control drew heavily on historical precedent, but, its application tended to be more complex than it had been in the past and became more involved as the mission of the U.S. command expanded. Looking to the future, contingencies of the magnitude and complexity of the Vietnam War cannot be ruled out. Should the United States again feel compelled to commit military forces, the need for a simple, well-defined, and flexible command structure on the U.S. side may conflict with the intricacies of indigenous political and military institutions and customs. Therefore, any future U.S. Military assistance to foreign nations must be predicated on clear, mutually acceptable agreements, on a -straight and direct line of authority among U.S. Military and civilian assistance agencies; on full integration of all U.S. efforts, and on the ability to motivate the host country's armed forces and governmental agencies to fight and win.

[88]

Return to the Table of Contents

|

Last updated 8 December 2003

|