CHAPTER IV

The Continuing Buildup: July 1966 July 1969

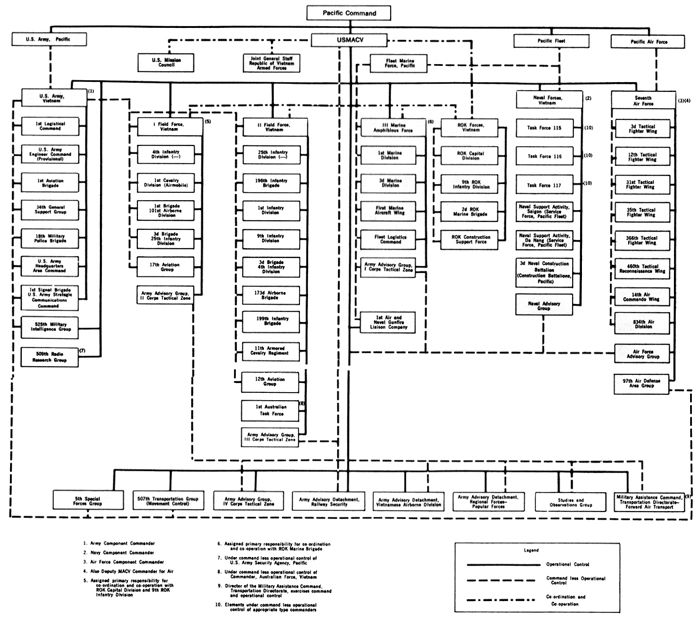

By mid-1966 U.S. forces in South Vietnam numbered about 276,000 men, 166,000 of them Army. In March the headquarters of II Field Force, Vietnam, had been activated under the command of Major General Jonathan O. Seaman at the same time that Major General Stanley R. Larsen's headquarters was redesignated I Field Force, Vietnam. In April 1966 the 2d Air Division was elevated to Seventh Air Force, and U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam, was established. With these changes, the command structure had matured to its full growth and henceforth was to undergo adaptation rather than major structural change until well after President Nixon announced the withdrawal of U.S. Forces in June 1969. (Chart 6)

A major organizational development during this period was the consolidation of the efforts of all U.S. agencies involved in Vietnamese pacification programs. Centralization of many diverse programs did not come easily, quickly, or even completely, but observers realized that a united effort was necessary in order to achieve better co-ordination among U.S. military and civilian agencies concerned with pacification. Especially important to success in this effort was the development of an organization that could effectively direct all programs after they were brought under the over-all control of the Military Assistance Command in the spring of 1967.

Shortly before General Westmoreland became the MACV commander he visited Kuala Lumpur, Malaya, in the company of Sir Robert G. K. Thompson, head of the British Advisory Mission to Vietnam, Alfred M. Hurt, Director of the United States Overseas Mission (later designated the U.S. Agency for International Development), and Barry Zorthian, head of the joint U.S. Public Affairs Office in Vietnam. The group spent several days studying the organization and techniques used by British and Malayan leaders during the Communist insurgency in the 1950s. On-the-

[64]

AMBASSADOR LODGE

spot observations confirmed the assumption that unity of command in the U.S. pacification effort in Vietnam was needed at the province level. Essentially, a single American "team captain" was required, who would act as the principal adviser to the province chief and be in charge of both civil and military matters.

Although the Vietnamese and the Americans were aware that successful pacification required both the restoration of security and the development of the nation, progress toward these objectives had been limited during 1964 and 1965. In 1965 the Vietnamese changed the term "pacification" to "rural reconstruction" and later to "rural construction." By the end of the year they had developed the concept of rural construction cadres. These cadres were to consist of highly motivated, specially trained teams that would move into hamlets, defend them, and initiate development programs. A decision was made to train eighty of these teams in 1966.

While the Vietnamese were attempting to make their pacification efforts more effective, the Americans were striving to improve U.S. support of these activities. The total U.S. effort involved several independent civil agencies as well as the military, but U.S. actions were not well co-ordinated. In January 1966 a meeting was held near Washington, D.C., to study ways of improving U.S. Support for rural construction activities. Senior representatives from all agencies of the U.S. Mission in Saigon, from the Washington Vietnam Coordinating Committee, and from other U.S. government agencies attended. The meeting revealed that all agencies recognized the need for improved coordination of U.S. Pacification efforts and that they favored the development of pacification and the training of cadres. Shortly thereafter, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge appointed Deputy Ambassador William J. Porter as coordinator of U.S. activities in support of rural construction and charged him to reconcile roles and duties within the U.S. Mission.

In February 1966 the Vietnamese Ministry of Rural Construction was redesignated the Ministry of Construction to dispel the

[65]

CHART 6-PACIFIC COMMAND RELATIONSHIPS, 1967

Source: USMACV Command History, 1967, Vol. 1, p. 123.

[66 -67]

mistaken idea that urban areas were excluded from this agency's concern. Because the Vietnamese translation did not make this distinction clear, Premier Nguyen Cao Ky coined the term "revolutionary development" (RD) to describe the mission of the ministry. In more definitive terms, the U.S. and Vietnamese governments agreed on the following statement:

RD is the integrated military and civil process to restore, consolidate and expand government control so that nation building can progress throughout the Republic of Vietnam. It consists of those coordinated military and civil actions to liberate the people from Viet Cong control; restore public security; initiate political, economic and social development; extend effective Government of Vietnam authority; and win the willing support of people toward these ends.

In order to consolidate the U.S. civilian pacification effort further, Ambassador Lodge established the Office of Civil Operations in November 1966. L. Wade Lathram was named the first director; he was responsible to Deputy Ambassador Porter for U.S. Civilian activities in support of revolutionary development and U.S. civil operations in the pacification program. At the same time, General Westmoreland elevated the MACV Revolutionary Development Support Division (created in late 1964 to co-ordinate military support of pacification) to directorate level, increased the staff, and named a general officer as director. To strengthen civil-military coordination, Major General Paul F. Smith was put in charge of revolutionary development in the office of Deputy Ambassador Porter. He was directly responsible for maintaining liaison with the Military Assistance Command in matters pertaining to U.S. And Vietnamese military support of the program. Directors for four regions-the Vietnamese corps areas-were appointed by Ambassador Lodge in December 1966. General Westmoreland directed the commanding generals of the III Marine Amphibious Force and of the I and II Field Forces and the senior adviser to the IV Corps to give all necessary assistance to the regional directors.

Despite these measures, effective integration of civil and military activities in support of the revolutionary development program remained an elusive goal. A major problem was the lack of personnel in the civilian agencies-the joint U.S. Public Affairs Office, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Office of the Special Assistant-to work at the province (sector) and district (subsector) levels. In fact, the only permanent U.S. advisers at the district level were those of the Military Assistance Command.

It was at the district and province levels that pacification had to begin and be made to work. Since military advisers were predominant at those levels and pacification depended on military

[68]

AMBASSADOR BUNKER

security, integration of the civilian and military efforts was essential. Realizing this urgent need, President Johnson, in conferences with President Thieu and other South Vietnamese leaders at Guam in March 1967, decided to integrate the civilian and military U.S. Support efforts under General Westmoreland. This decision heralded a major change in U.S. command arrangements that would have a lasting effect on the combined pacification effort.

On the part of the United States, the first organizational and personnel changes came with the arrival in Saigon of Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker, who replaced Ambassador Lodge in April 1967. Deputy Ambassador Porter was succeeded in office by Eugene M. Locke. In addition, Presidential Assistant Robert W. Komer, who had been overseeing revolutionary development support activities at the Washington level since March 1966, was assigned to General Westmoreland's headquarters. In May 1967, Ambassador Bunker announced that the U.S. Mission's responsibility for the revolutionary development program was being integrated under the Military Assistance Command in a single-manager arrangement, and that General Westmoreland would assume the responsibility under the over-all authority of the ambassador. There were two basic reasons for assigning the task to General Westmoreland. First, security, a prerequisite to pacification, was a primary responsibility of the Vietnamese armed forces, which were advised by the Military Assistance Command-Westmoreland's headquarters. Second, the greater part of U.S. advisory and logistic resources were under General Westmoreland's control.

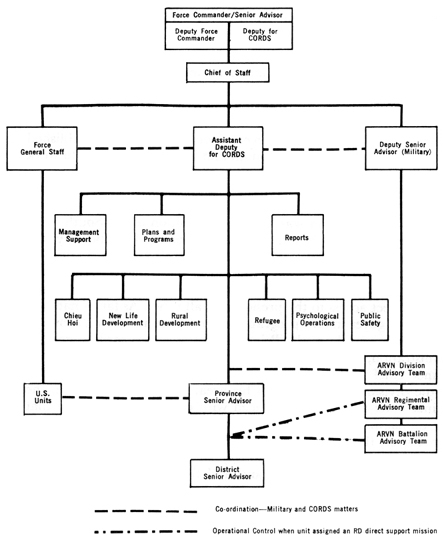

Presidential Assistant Komer was appointed Westmoreland's deputy for Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS) with the rank of ambassador, and the four regional directors of the Office of Civil Operations were assigned as deputies to the four senior advisers to the Vietnamese corps. The Embassy's Office of Civil Operations and MACV's Revolutionary Development Support Directorate (RDSD) merged to form, within the

[69]

AMERICAN EMBASSY ON THONG NHUT BOULEVARD IN DOWNTOWN SAIGON

Military Assistance Command, the office of Assistant Chief of Staff for CORDS. Mr. Lathram, who had been the director of the Civil Operations office, was given this new position, and Brigadier General William A. Knowlton, who had been the RDSD director, became his deputy. Of the resulting arrangement, Ambassador Bunker said: "Such a unified civil-military US advisory effort in the vital field of RD is unprecedented . . . . RD is in my view neither civil nor military but a unique merging of both to meet a unique wartime need." Thus the single-manager concept had become a reality. It was based on the realization that the pacification effort and the war fought in the field were inseparable elements of the Vietnam conflict.

On the part of the Vietnamese, organizational changes were more slowly realized than in the U.S. camp. At the national level the government of South Vietnam, in November 1967, established the Central Revolutionary Development Council, headed by the Prime Minister. Members of the Central Council were the heads of the key ministries responsible for the many aspects of the pacification programs, notably the Ministers of Defense, Interior, Public

[70]

Works, Land Reform and Agriculture, Health, Refugees, and Chieu Hoi and the commander in chief of the army and all corps commanders. The Minister of Revolutionary Development served as Secretary General and his ministry was the Central Council's executive agency. Throughout South Vietnam, Regional Revolutionary Development Councils were formed at the corps, special zone, provincial and municipal, and district levels. Thus, by the end of 1967, a revolutionary development network was established that would put the country's human and material resources to work on the pacification effort.

The revolutionary development network, however, was not wholly complementary to the U.S. single-manager concept for pacification. The reason was the special position of the South Vietnamese province chief in the chain of command. Traditionally, the province chief was charged with security as well as general administration of all government services within his province. Appointed by the president, he was responsible to the president for his province and had direct access to the president at all times. As far as national policy and government programs were concerned, the province chief was responsible to the Prime Minister, and regarding general administration, to the Minister of the Interior. In addition, the province chief was subject to pressures from the corps commander and the division commander in his area. In a very real sense, the province chief was constantly faced with conflicts of authority that were damaging to the national administrative machinery. To a lesser degree, this situation also applied to the district chiefs.

The integration of revolutionary development support under the Military Assistance Command and the staff realignments that resulted had a profound influence on the U.S. Advisory effort. First, a single U.S. team chief was appointed for each province. In mid-1967, when the program got under way, twenty-five of these province senior advisers were military and nineteen were civilian. Second, the MACV subsector (district) advisory team became the nucleus of the CORDS staff at the district level. The district staff now included both military and civilian personnel, and its chief was responsible for the management of support activities pertaining to revolutionary development. The head of the team was redesignated the district senior adviser. Finally, staff elements at the field force and Marine Amphibious Force levels, which had previously been engaged in support activities, were each integrated into separate CORDS staff offices. Each CORDS office dealt directly with the province senior advisers within the corps tactical zones regarding military operations related to the revolutionary development program. Thus, at the field force level the deputy senior

[71]

CHART 7-CORDS FIELD ORGANIZATION

Source: USMACV Command History, 1967, Vol. II, p. 589.

[72]

adviser (a military officer, not to be confused with the Civil Operations regional director, who had been designated deputy for CORDS) ceased to exercise command supervision over the province (sector) advisory teams within the corps zone. The deputy senior adviser did, however, continue to be responsible for the advisory activities of military units. Thus, two separate chains of command -developed: one for military and civil advisory efforts pertaining to pacification, and one for military advisory efforts pertaining to Vietnamese units. These field relationships remained essentially unchanged from 1967 onward. (Chart 7)

Response to the Communist Threat in the North

Following the introduction of major U.S. Forces in South Vietnam in 1965, there was a gradual buildup of enemy forces in the northern part of the I Corps Tactical Zone. To counter this threat, the I Corps area was reinforced as much as possible from U.S., Vietnamese, and Free World forces already in South Vietnam. In August 1966 the Republic of Korea Marine Brigade was moved from the II Corps area to the southern part of the I Corps. This action permitted greater concentration of U.S. 1st Marine Division forces in the Da Nang area, allowing in turn the concentration of the 3d Marine Division in the two northernmost provinces. During early 1967, further concentration of forces in the northern part of the I Corps area was carried out by moving more units from the central and southern parts closer to the Demilitarized Zone.

By April 1967, increased enemy activity prompted General Westmoreland to form Task Force OREGON and send it to the southern part of the I Corps zone, thereby freeing additional U.S. Marine units to move farther north. Task Force OREGON was comprised of a provisional headquarters, division support troops from various U.S. Army units, and three brigades taken from areas where they could be spared with the least risk. These brigades were the 196th Light Infantry Brigade from the III Corps area, and the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division and the 3d Brigade of the 25th Infantry Division (subsequently redesignated the 3d Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division) from the II Corps zone. Later in the year, the 3d Brigade of the 25th Division and the 1st Brigade of the 101st Division were replaced by the newly arrived 198th and 11th Light Infantry Brigades. In September 1967 Task Force OREGON became the 23d Infantry Division (Americal).

The original plan for reinforcing the I Corps zone called for U.S. Army forces to conduct operations south of DA Nang, allowing the U.S. Marines to concentrate farther north. This division of

[73]

responsibility according to sectors was designed to avoid operational and logistic confusion, but the concept had to be abandoned when the enemy buildup along the Demilitarized Zone and in Laos increased to the point where further U.S. deployments to the area were needed. General Westmoreland moved U.S. Army forces to the middle of the northern I Corps area to support the U.S. Marines, with the result that units of the two services intermixed and the command and control structure became overburdened. To relieve the situation, the headquarters of the 1st Cavalry Division was moved north early in 1968. More U.S. Army units followed. The 2d Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, moved to the vicinity of Hue in January, and in February both the 27th Marine Regimental Landing Team and the 3d Brigade, 82d Airborne Division, were airlifted from the United States to the I Corps Tactical Zone.

The controlling and planning capability of the III Marine Amphibious Force headquarters became severely taxed by the presence of these additional Army and Marine forces. General Westmoreland responded to the command and control problem by establishing MACV Forward headquarters in the Hue-Phu Bai area on 9 February 1968. From the clew headquarters, General Creighton W. Abrams, the deputy MACV commander, exercised control for General Westmoreland over all joint combat and logistical forces-Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine-deployed in the northern I Corps area. These forces were being assembled to meet a major enemy offensive, which was expected in Quang Tri Province.

One month later on 10 March 1968, MACV Forward, having served its purpose, was converted to a corps headquarters and designated Provisional Corps, Vietnam, under the command of Lieutenant General William B. Rosson. General Rosson exercised operational control over the 3d Marine Division (Reinforced), the 1st Cavalry Division, the 101st Airborne Division (-) (Reinforced), and assigned corps troops. The new corps also co-operated closely with the Vietnamese 1st Division in the area.

The I Corps zone was divided into two parts by a boundary through Thua Thien Province that ran roughly north of DA Nang. The Provisional Corps, Vietnam, which was designated XXIV Corps on 12 August 1968, had operational control over ground tactics: units north of the boundary, while the III Marine Amphibious Force exercised operational control of the corps in the north and of all tactical units south of the boundary. Thus freed from the task of directing the battle in the north on a day-to-day basis, the commanding general of the Marine amphibious force, Lieutenant General Robert E. Cushman, Jr., USMC, was able to concentrate

[74]

on the entire I Corps area, especially on CORDS functions and logistic support responsibilities.

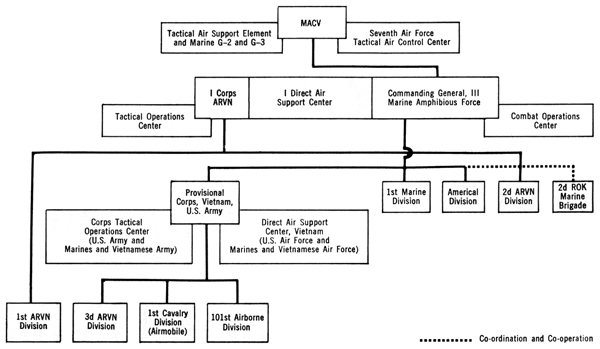

As operations in the north expanded, General Westmoreland decided that an important adjustment in the tactical aircraft control system in the I Corps area was needed. Before 1968 there had been two managers for air assets in the I Corps zone: the deputy MACV commander for air operations, who was also the commander of the Seventh Air Force, had operational control of the Seventh Air Force's men and equipment and of any Navy air support from Task Force 77; and the commanding general of the III Marine Amphibious Force had operational control of the resources of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. This air unit supported the U.S. Marines in the I Corps area, while the Seventh Air Force supported U.S. Army units, the Korean marine brigade, and the Vietnamese forces. General Westmoreland considered it "of paramount importance to achieve a single manager for control of tactical air resources"; therefore, on 8 March 1968 he appointed his deputy for air operations, General William W. Momyer, as manager of all air assets. The system for tactical air support was adjusted to conform with the new ground organizational structure and became effective on 1 April 1968. (Chart 8)

The terrain and enemy activity in the I Corps zone made logistic support particularly difficult, and the intermixing of Army and Marine units created additional complications. The situation

[75]

CHART 8-ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE AND COMMAND RELATIONSHIPS OF I CORPS: MARCH 1968

Source: USMACV Command History, 1968, Vol. I, p. 438.

[76]

there produced unusual command arrangements for supporting U.S. Forces Logistic support in Vietnam was organized on an area basis. In the I Corps area, the commander of U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam, was responsible for common item support, base development (excluding U.S. Air Force bases), and real estate services for all U.S. And Free World forces. Furthermore, he provided logistic support for military operations at ports and beaches as well as items peculiar to Navy and Coast Guard support.

These responsibilities were carried out by the Naval Supply Activity at DA Nang. In addition, General Cushman supplied items needed exclusively by Marine units in the I Corps area. General Westmoreland, as commanding general of U.S. Army, Vietnam, was responsible for the supply of common items in the other three corps zones. Although Secretary of Defense McNamara had directed in late 1966 that plans be developed for the Army to assume common supply support responsibility throughout South Vietnam, agreement on procedures acceptable to all services had not been achieved. With the buildup of Army forces in the I Corps zone, however, Navy and Marine facilities could no longer meet the increased demand, so U.S. Army, Vietnam, had to expand logistic support efforts into this area. The DA Nang Support Command was established as a major element of the 1st Logistical Command to direct the sixty-five Army support units that USARV deployed to the I Corps area. Five of these units provided direct support to the Navy and Marines, and nine assumed some of the Navy's responsibilities, such as an over-the-beach logistic operation at Thon My Thuy. While the logistic support operations in the I Corps area during this period were efficiently carried out, they were accomplished through a complicated control arrangement involving Army, Navy, and Marine headquarters.

At the end of 1965 the commanding general of the III Marine Amphibious Force was the tactical commander of Marine forces in the I Corps Tactical Zone as well as the senior adviser to the Vietnamese commanding general there. He was also the Navy component commander at MACV headquarters and was therefore charged with area coordination, logistic support, and base development. In order to ease the burden of the Marine commander, General Westmoreland recommended to Admiral Sharp, Commander in Chief, Pacific, that a Navy command be established in Vietnam. Consequently, on 1 April 1966, U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam, was established with Rear Admiral Norvell G. Ward as com-

[77]

mander. Naval Forces, Vietnam, assumed command of the Navy units in South Vietnam and, although assigned to the Pacific Fleet, was placed under the operational control of General Westmoreland. Concurrently, the III Marine Amphibious Force, together with its organic and assigned units, was designated a single service command assigned to the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, and was placed under the operational control of General Westmoreland.

In 1966 a concept was developed for extending U.S. combat power into the Mekong Delta area where the enemy was strong and where the United States had lacked the resources to assist the Vietnamese Army in achieving control. MACV headquarters organized what was originally called the Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force, soon to be known as the Mobile Riverine Force. The original plan called for basing one U.S. Army division in a location where it could operate along the Mekong and Bassac Rivers. Army troops were to be supported by U.S. Navy river assault groups, and one brigade of the division would be stationed aboard converted LSTs (landing ships, tank). This concept required new and unusual command relationships.

General Westmoreland proposed that one brigade of the arriving 9th Infantry Division be the Army component of a mobile joint task force. The Navy component would consist of tactical and logistic ships and craft to support the brigade afloat on riverine operations. General Westmoreland further proposed that the joint task force be commanded by the assistant commander of the 9th Division, who would have a small joint staff of operations, logistics, and communications personnel.

In Honolulu General Waters, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, concurred with General Westmoreland's proposal. Admiral Sharp and the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, however, favored a command arrangement in which the naval force would be under the operational control of the commander of the River Patrol Force (a task force, CTF 116, which was already conducting operations in the Mekong Delta) and would operate in support of the ground forces involved. A compromise solution ultimately developed, which placed U.S. Army units conducting riverine operations in the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones under the operational control of the commanding general of II Field Force. He could exercise control through a designated subordinate headquarters, such as the 9th Infantry Division. According to this arrangement, Navy units would be under the operational control of Admiral

[78]

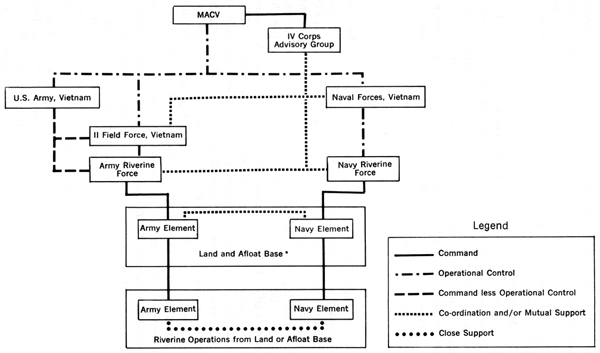

CHART 9-COMMAND RELATIONS FOR RIVERINE OPERATIONS

a The Army will provide the base commander both ashore and afloat. The Navy

will provide its appropriate share of personnel for local base defense and primary

efforts directed toward provision of gunfire support and protection against

waterborne threats.

Source: CINCPAC Command History, 7966, Vol. II, p. 620.

[79]

Ward, who could also operate through a designated subordinate Navy commander. (Another task force, CTF 117, was established to control Navy riverine forces.) Finally, riverine operations would be conducted with Army and Navy units commanded separately, but the Navy would provide close support through procedures of mutual coordination(Chart 9)

The Mobile Riverine Force began operations on 1 June 1967 with Operation CORONADO in Dinh Tuong Province. The 2d Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division and the Mobile Riverine Force conducted a two-month offensive in the vast waterways of the Mekong Delta with extraordinary success. The force continued aggressive operations until 25 August 1969, when the riverine force was deactivated and its mission and equipment were taken over by the Vietnamese Navy Amphibious Task Force 211.

Additional Military Assistance Commands

The enemy's 1968 Tel offensive revealed serious weaknesses in the Vietnamese organization for the defense of the Saigon area. For example, the commanding general of the Vietnamese III Corps had the basic responsibility for the capital, but he had no control over National Police units in his area. During the Tel offensive emergency, General Cao Van Vien, the chairman of the joint General Staff, temporarily assumed command of all Vietnamese forces, including the National Police, within the Capital Military District. No permanent structure was established, however, and when the enemy resumed his attacks in May, the III Corps commanding general assumed personal command of all forces in the Saigon area. In June 1968 Major General Nguyen Van Minh was designated Military Governor of Saigon and of the adjoining Gia Dinh Province. Under the operational control of the III Corps commander, General Minh was given primary responsibility for the defense of the capital and control of all Vietnamese government forces charged with the security of Saigon and Gia Dinh. These forces included the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, the General Reserve, Regional and Popular Forces, the National Police, and the Military Police in the district. The Vietnamese Army commander of the Capital Military District became his deputy.

Corresponding adjustments were made on the U.S. side. During the Tel offensive, a command group from the II Field Force had moved to Saigon. This temporary headquarters, called Hurricane Forward, controlled all U.S. Forces in the Saigon-Gia Dinh area and had the mission of advising the Vietnamese armed forces there. In May, Hurricane Forward was reconstituted and dispatched to

[80]

GENERAL ECKHARDT

Saigon. The headquarters was redesignated Task Force Hay (for Major General John H. Hay, Jr., Deputy Commanding General, II Field Force, Vietnam). On 4 June 1968, this temporary arrangement became permanent, and General Hay was officially appointed senior adviser to General Minh, the Military Governor, and commander of U.S. Forces defending Saigon and Gia Dinh. The forward headquarters was designated Capital Military Assistance Command, with the mission to plan and execute the defense of the Saigon-Gia Dinh area in coordination with the commanders of the U.S. Seventh Air Force and Naval Forces, Vietnam, and the Vietnamese Military Governor of Saigon-Gia Dinh. This move significantly strengthened the U.S. And Vietnamese organization for the defense of the Saigon capital area.

In another development, the senior adviser to the IV Corps Tactical Zone, Major General George S. Eckhardt, on 8 April 1969, assumed as an additional duty the position of Commanding General, Delta Military Assistance Command. The Delta Military Assistance Command was established to control the various ,U.S. Army units based in the delta area, including the U.S. 9th Infantry Division.

U.S. Army Logistical Advisory Effort

In May 1966 General Westmoreland asked Lieutenant General Jean E. Engler, Deputy Commanding General, U.S. Army, Vietnam, to study whether USARV headquarters should assume the Army's logistical advisory functions, which at the time were being performed by MACV's J-4 section, the Logistics Directorate. After completion of his survey, General Engler made several observations and recommendations. The entire Army military assistance and advisory effort should, he contended, be the exclusive function of U.S. Army, Vietnam, freeing the Military Assistance Command to concentrate on the control of its components. General Engler concluded that MACV was no longer operating as a military assistance command in the true sense of the term, since U.S. tactical

[81]

GENERAL PALMER. (Photograph taken after his promotion to four-star general.)

Forces had been so greatly increased and their mission expanded. The newly instituted practice of funding military assistance programs through the individual services had further changed MACV's role. General Engler maintained that logistics should not be separated from operations and advisory activities, and therefore these functions should be performed by U.S. Army, Vietnam, in an expanded role as a full-fledged Army component.

As a result of General Engler's appraisal, logistic advisory functions were transferred to USARV headquarters, but the broader question of USARV's status was not resolved. Lieutenant General Bruce Palmer, Jr., who succeeded General Engler on 1 July 1967, elevated the logistic advisory group within the USARV staff to a general staff section, which he designated the Military Assistance Section. This action was prompted by General Palmer's conviction that logistic advisory responsibilities were equal in importance to the mission of supporting U.S. troops.

In the summer of 1967 a study called Project 640 was conducted by the Military Assistance Command. Its purpose was to examine the problems that had arisen because the MACV organization lacked a single staff focal point to coordinate and monitor all aspects of the assistance effort. As a result of the study, General Westmoreland established the post of Assistant Chief of Staff, Military Assistance, in the MACV staff to provide that focus. He also appointed a temporary committee to determine what functions could be transferred between MACV and USARV headquarters. On the committee's recommendation, logistic advisory functions were transferred from U.S. Army, Vietnam, back to the Military Assistance Command in February 1968.

During the period from mid-1966 to mid-1969 the authorized strength of U.S. Forces in South Vietnam rose from about 276,000

[82]

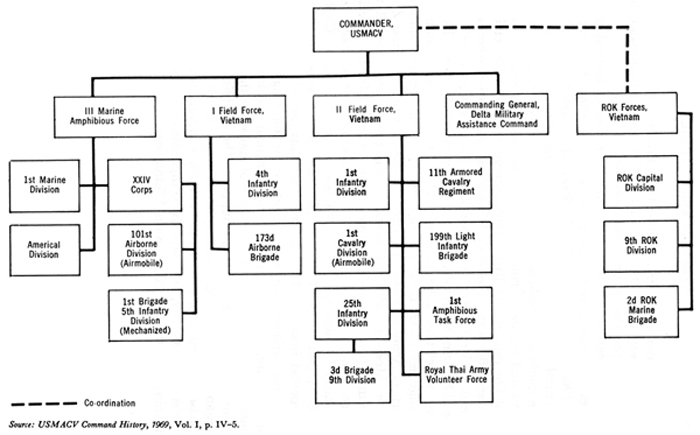

CHART 10-TACTICAL GROUND FORCES

Source: USMACV Command History, 1969, Vol. I, p. IV-5.

[83]

men to a peak of 549,000. In June 1969, President Nixon announced from Midway Island the first of the U.S. force withdrawals, and graduated reductions continued from then on.

By the end of 1969 the control structure of major tactical ground forces was essentially the same as the one developed during 1965 and 1966. (Chart 70) The 1966-1969 period was not marked by basic structural changes in the chain of command. The modifications that were made were evolutionary and consistent with tactical requirements and expanded command responsibilities. By establishing the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support, U.S. Civil and military efforts in support of Vietnamese pacification were at last united under General Westmoreland, the single manager. After the U.S. Army's XXIV Corps was deployed in the I Corps Tactical Zone, which used to be the Marine Corps' exclusive area, command arrangements were developed to control and support the combined efforts of Army and Marine forces. In the IV Corps Tactical Zone, of the Mekong Delta, command arrangements were devised for directing joint Army-Navy operations of the Mobile Riverine Force. Finally, the Capital Military Assistance Command was organized to support the Vietnamese Saigon-Gia Dinh Capital Military District. MACV's command and control structure during the period from mid-1966 to mid-1969 thus proved to be flexible and strong enough to adjust not only to the doubling of U.S. Forces in Vietnam, but also to the expanded tactical and logistic requirements, as well as to the added mission of managing the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support. The established command organization also held the promise of being able to cope with the phased reduction of U.S. Forces in South Vietnam, which began in the summer of 1969, and with the complicated process of gradually turning over the war effort to the Vietnamese.

[84]

Return to the Table of Contents

|

Last updated 8 December 2003

|