CHAPTER III

The Buildup of U.S. Forces: July 1965 July 1966

In the Vietnam War, 1965 was a year of grave decisions. The North Vietnamese regarded the year as the beginning of the war's final phase, during which the Army of the Republic of Vietnam was to be destroyed by direct military action and the government and the people of South Vietnam were to lose their will to fight. The Communist hopes came close to being realized: the Saigon government had been weakened by a series of coups following the 1963 overthrow of President Diem; the Vietnamese armed forces had suffered a series of defeats that led to widespread demoralization; and government control, especially in the countryside, was eroding. The Viet Cong were expanding their power within the country, and beginning in 1965 the first North Vietnamese Army units in regimental strength were moving into the Central Highlands region. Enemy infiltration from the north was increasing and had reached a rate of more than one thousand men per month.

At this critical juncture, U.S. authorities came to the conclusion that the Vietnamese armed forces would no longer be able to contain the rising military threat to the security of their country without extensive additional military and economic assistance. This assistance, Ambassador Maxwell D. Taylor and General Westmoreland recommended, would have to include commitment of U.S. ground combat forces. President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to stand firmly behind the South Vietnamese people and defeat Communist aggression in Southeast Asia. Thus the year 1965, for the United States, was the year of military commitment.

The crucial events that occurred between July 1965 and July 1966 greatly affected the command and control arrangements in Vietnam. The rapid buildup of U.S. forces in Vietnam, the initiation of combat operations by U.S. Forces, the expansion of logistical support operations, and the introduction of Free World Military Assistance Forces in a combat and combat support role all contributed to changes in a command structure that had originally been designed to accommodate only a U.S. military assistance mission.

[47]

AMBASSADOR TAYLOR

Essentially, there was no change in the role and function of the U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam. General Taylor continued to have over-all responsibility for all U.S. activities in Vietnam. To assist the ambassador and to provide a mechanism for high level co-ordination and discussion, the Mission Council had been formed in July 1964. The Mission Council consisted of the senior officials of the civil and military elements of the U.S. Mission meeting together on a weekly basis. Under the chairmanship of the ambassador, there was frank and complete discussion of problems and proposals covering the entire range of U.S. Activities General Westmoreland advised the council on military developments and plans. New U.S. plans and programs were often proposed to senior Vietnamese officials as they met periodically with the Mission Council. Thus the Mission Council was the policy-forming body of the United States in Saigon and gave co-ordinated guidance and direction to all U.S. agencies in South Vietnam.

As mentioned earlier, doctrine for the U.S. armed forces prescribed a separate Army component commander subordinate to the unified commander; but as early as 1963 military planners had determined that an Army component headquarters would be unnecessary and redundant. Instead, the joint force commander, acting either as a U.S. or combined commander, should also be his own Army component commander. An important consideration supporting this arrangement was the desire to align the U.S. Military structure in South Vietnam with that of the Vietnamese armed forces. Since their joint General Staff exercised operational control over the Vietnamese Army forces in the field, while headquarters of the Vietnamese Army had command less operational control, it was logical and practical for the MACV commander similarly to retain operational control of U.S. Army forces.

As a result, General Harkins, the MACV commander, had been designated the Army component commander in August 1963, and

[48]

AMERICAN EMBASSY ANNEX BUILDING ON HAM-NGHI BOULEVARD IN DOWNTOWN SAIGON

the commander of the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, Brigadier General Joseph W. Stilwell, had been appointed the deputy Army component commander. General Harkins thus exercised direct operational control over U.S. Army forces in Vietnam, while General Stilwell retained command less operational control. In March 1964, when the support group was redesignated U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam, this arrangement continued unchanged.

In late 1964 and early 1965, when a major buildup of U.S. Army ground combat forces was imminent, planners from U.S. Army, Pacific, and the Department of the Army began to restudy current command arrangements. The ever-growing responsibilities of the Army Support Command, especially its duties as the U.S. Army component headquarters, precluded its reorganization into a logistical command, as envisaged in contingency plans. The ob-

[49]

vious solution was to establish a separate logistical command. These developments strengthened the arguments of planners who wanted an Army headquarters to command U.S. Army ground forces.

In view of the possible deployment of major Army ground combat forces to Vietnam, the Army Chief of Staff, General Harold K. Johnson, recommended to the joint Chiefs in March 1965 that a separate U.S. Army component command, under the operational control of the MACV commander, be established in Vietnam. Under his proposal, administrative and logistical functions concerning U.S. Army activities would be transferred from MACV headquarters to the new component command; the Army advisory effort would be similarly shifted, although the MACV commander would retain operational control. Under this arrangement, the Military Assistance Command would be relieved of administrative functions not directly related to combat or tactical operations.

The Commander in Chief, Pacific, Admiral Sharp, and the MACV commander, General Westmoreland, both opposed General Johnson's recommendation. On the other hand, MACV's Chief of Staff, Major General Richard G. Stilwell, held that an Army component command would prove to be a valuable co-ordinating link between the Military Assistance Command, the U.S. Army, Pacific, and the U.S. Army Support Command.

Through July 1965 there was a constant exchange of views between General Westmoreland and General John K. Waters, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, concerning the establishment of a separate Army component command under the Military Assistance Command. General Waters favored an Army component command with its own commander. General Westmoreland, however, made the following proposals: that the U.S. Army Support Command be redesignated U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV) ; that he personally retain the responsibilities of the Army component commander and be made Commanding General, U.S. Army, Vietnam; that the incumbent commanding general of the U.S. Army Support Command be redesignated Deputy Commanding General, USARV; and that all Army units deployed to Vietnam be assigned to the USARV headquarters. General Westmoreland further recommended the establishment of several Army corps-level headquarters in Vietnam which, under his operational control, would conduct U.S. combat operations in their respective tactical zones. Westmoreland's proposals were approved by General Waters and the Department of the Army, and on 20 July 1965 a letter of instruction from U.S. Army, Pacific, headquarters spelled out the new command relationship.

[50]

The appointment of General Westmoreland as USARV's commanding general was a step away from the creation of a true Army component command. Although the MACV commander had been the Army component commander since August 1963, the senior Army headquarters in Vietnam had had its own commanding general. With the change of July 1965, both positions were occupied by the same individual, General Westmoreland. Thus he was put in the position of having to serve two masters: the Commander in Chief, Pacific, and the Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific. Similarly, U.S. Army organizations in Vietnam were responsible to the head of the Military Assistance Command for combat operations and to the commander in chief of U.S. Army; Pacific, for Army matters. The overlapping chains of command resulted in duplication and confusion within the MACV-USARV structure.

The command structure which evolved in Vietnam during 1965 bore striking resemblance to Army command arrangements that had existed in the Pacific and Europe during World War II and in the Korean War. During World War II General Douglas MacArthur had been both Commander in Chief, Southwest Pacific Area, and Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, the Army component. Operational control of U.S. Army combat forces had rested with General MacArthur as the commander of the Southwest Pacific Area, a position analogous to that of the MACV commander. Far East headquarters, however, had retained operational control over certain combat support and combat service support units not directly involved in the combat areas. The same situation had existed in Europe, where General Dwight D. Eisenhower, as Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force, had retained operational control over U.S. Army combat forces. General Eisenhower had also been his own Army component commander as commanding general of the European Theater of Operations.

During the Korean War General MacArthur had served as Commander in Chief, United Nations Command, and Commander in Chief, Far East. As such he had exercised direct operational control over U.S. Army combat forces in Korea. He had exercised command less operational control of all U.S. Army organizations in his role of Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces, Far East, a command generally analogous to U.S. Army Forces in the Far East and the European Theater of Operations in World War II and to U.S. Army, Vietnam. This arrangement had prevailed until after the prisoner of war riots at Koje-do in 1952, when General. Mark Clark succeeded MacArthur as the Far East commander in chief

[51]

HEADQUARTERS OF THE U.S. ARMY, VIETNAM

and established a separate Army component-Army Forces, Far East. This arrangement lasted until the fighting stopped in 1953.

In March 1965 General Westmoreland had advised Admiral Sharp that if major U.S. Ground combat forces were to be deployed to Vietnam, a combined corps-level field command would be needed. The MACV commander also indicated that he tentatively planned to designate his deputy as the commander of such a headquarters. Following discussions between the Military Assistance Command, the U.S. Army, Pacific, the Pacific Command, the Department of the Army, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Secretary of Defense McNamara in mid-May approved a combined field forces headquarters in Vietnam under the deputy MACV commander. However, further debate between the interested headquarters postponed its activation. Eventually, the Joint Chiefs approved deployment of a U.S. Army corps headquarters to Vietnam and directed the Army Chief of Staff, General Johnson, to develop

[52]

the necessary plans. There were two main reasons for adopting the term "field force" rather than "corps" for the tactical corps-level headquarters about to be introduced into South Vietnam. First, as General Westmoreland pointed out, since the new headquarters was to operate in conformance with existing South Vietnamese corps zones, having two corps designations-one American and one South Vietnamese-in the same tactical zone would have been confusing. Second, the standard U.S. corps headquarters was a fixed organization. Field forces headquarters, on the other hand, would be more flexible and could be tailored to fit precisely the individual mission and could be adjusted to future changes, notably to further expansion of the U.S. effort.

Late in June, after further debate, the joint Chiefs concluded that the field forces headquarters should be joint instead of Army. The Joint Chiefs believed that Westmoreland's plans envisaged control by this headquarters over U.S. and Free World ground combat organizations in both the I and II Corps Tactical Zones, thereby bringing the forces of the U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Army, and Republic of Korea under one tactical corps-level command. The Joint Chiefs therefore directed Admiral Sharp, the Pacific commander in chief, to plan the organization of a joint field forces headquarters and to continue planning for the activation of a combined corps-level headquarters.

These instructions were confusing because two separate concepts for the field forces headquarters were entangled. In an effort to clarify the situation, General Westmoreland explained to Admiral Sharp that he intended the headquarters to be evolutionary. In the beginning, the field forces headquarters would be a small, provisional organization, to be known as Task Force Alpha, and would control only U.S. Army forces in the II Corps Tactical Zone. After the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) reached Vietnam, Task Force Alpha would be expanded and designated Field Forces, Vietnam. In the event that Marine Corps forces in the I Corps Tactical Zone should come under the control of Field Forces, Vietnam, the headquarters could be augmented by Marine personnel. General Westmoreland contended that the headquarters should not include Navy or Air Force representation, since the support provided by these services would continue to be controlled by the Military Assistance Command. Westmoreland's proposal was adopted by the joint Chiefs, and on 1 August 1965 Brigadier General Paul F. Smith temporarily assumed command of the newly activated Task Force Alpha until the arrival of the designated commander, Major General Stanley R. Larsen, on 4 August.

[53]

The Military Assistance Command gave the task force two missions: to exercise operational control over designated U.S. And Free World units and to provide combat support to South Vietnamese armed forces. In coordination with the Vietnamese commanding generals of the II and III Corps, Task Force Alpha would participate in the defense of U.S. And Vietnamese installations, conduct unilateral or combined offensive operations, and maintain close liaison with MACV's senior advisers at Vietnamese corps, division, and sector (province) levels. These advisers would be the task force's principal points of contact with Vietnamese troops. General Westmoreland emphasized that the relationship between the commanding general of the task force and the Vietnamese Army corps commanders would be one of coordination and cooperation.

Task Force Alpha was redesignated Field Forces, Vietnam, on 25 September 1965, as plans were being made for a second Army corps-level headquarters in Vietnam. This plan was approved by Secretary of Defense McNamara in December 1965, and Field Forces, Vietnam, was redesignated I Field Force, Vietnam. The new corps-level headquarters was designated II Field Force, Vietnam, and assigned responsibility for the III Corps zone.

Viet Cong attacks against U.S. installations at Pleiku and Qni Nhon early in 1965 had prompted President Johnson to order the evacuation of all dependents of U.S. government officials in Vietnam. Meanwhile, General Westmoreland and the Joint Chiefs discussed sending a Marine expeditionary brigade and additional Army forces to Da Nang and other critical locations in Vietnam. The Joint Chiefs recommended to Secretary McNamara that the Marine brigade be committed and that additional Air Force tactical squadrons be moved to the western Pacific and to Vietnam. General Westmoreland agreed, but he advised Admiral Sharp and the Joint Chiefs that more security forces might be needed, especially in DA Nang, in the Saigon-Bien Hoa-Vung Tau area, and in the Nha Trang-Cam Ranh Bay complex. There had been some discussion between General Westmoreland, Admiral Sharp, and the Joint Chiefs over the possibility of sending the Army's 173d Airborne Brigade instead of the Marine's brigade. The 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade was selected, however, and the leading elements went ashore on 8 March. The original mission of the brigade was entirely security-oriented, and the force was directed

[54]

not to engage in day-to-day offensive operations against the Viet Cong.

Early in March 1965, General Westmoreland proposed a significant change in basic U.S. policy in Vietnam. In response to an inquiry from the joint Chiefs of Staff, the MACV commander noted that the only way to forestall a Viet Cong take-over of the country-except in the major population centers that were under the control of the government of Vietnam-was to commit additional U.S. and Free World forces. These forces would have to be prepared to perform whatever military operations were needed. General Westmoreland's proposal was supported by Admiral Sharp and the Joint Chiefs, and in the next several weeks an accelerated planning effort was undertaken involving all four service departments, as well as the joint Chiefs, Admiral Sharp, and General Westmoreland. The resulting strategy, to be carried out by the Pacific Command, called for U.S. forces to secure coastal enclaves from which they could engage in operations against the enemy in co-ordination with the Vietnamese armed forces, and where they could build major logistical bases to support future combined offensive operations. Strategy also dictated that the following force groupings be sent to Vietnam: a U.S. Marine Corps division (supported by an air wing), tentatively designated III Marine Expeditionary Force, to be deployed in the I Corps Tactical Zone; and U.S. Army and Free World forces, to be deployed in the II and III Corps areas. Such an arrangement would provide for a comparatively simple operational chain of command extending directly from the Military Assistance Command to the III Marine Expeditionary Force in the I Corps zone, and to the two Army field forces headquarters in the Vietnamese II and III Corps zones.

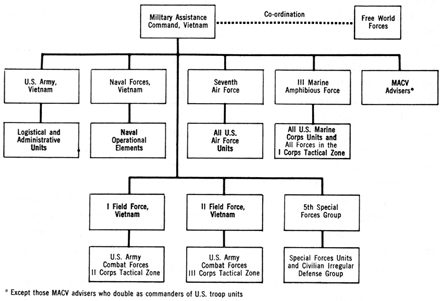

Late in 1965 these plans were modified to include two U.S. Marine Corps divisions and their organic air wings in the I Corps Tactical Zone under the commanding general of the III Marine Amphibious Force, as well as additional U.S. Army forces for the II and III Corps zones. The basic concept for operational control of these forces remained unchanged. In South Vietnam the Marine Corps would be responsible for a geographic area of operations equivalent to the I Corps Tactical Zone under the operational control of General Westmoreland, while the U.S. Army would have similar assignments in II and III Corps zones. In the Mekong Delta the existing advisory structure remained in force. With the exception of some modifications for the delta area-the Vietnamese IV Corps Tactical Zone-these arrangements prevailed until the 1968 Tet offensive, which prompted significant U.S. reinforcement of the I Corps Tactical Zone. (Chart 5)

[55]

CHART 5-MILITARY ASSISTANCE COMMAND, VIETNAM, 1965

Except those MACV advisers who double as commanders of U.S. troop units

Source: Report on the War in Vietnam (as of 30 June 1968) by Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, USN, and General William C. Westmoreland, USA (Washington: 1969), Section II, Chapter III, p. 102.

Organization of Advisory Effort

Command. And control of U.S. military advisers was exercised in two separate and distinct ways. For Navy and Air Force advisers, the chain of command ended with the respective service component commanders at the MACV level. In the case of the Navy, the commander of the Naval Advisory Group reported directly to the Naval component commander, who was the Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam; a single individual filled both positions. In the case of the Air Force, the chief of the Air Force Advisory Group at MACV headquarters was also the commanding general of the 2d Air Division as well as the Air Force component commander in Vietnam. In other words, the advisory efforts of the Navy and the Air Force were under the operational control of their respective service component commanders, who received direction and guidance from General Westmoreland.

Army advisers, on the other hand, were under the operational control of the MACV commander. During 1965 a total of nine U.S.

[56]

Army advisory groups reported directly to General Westmoreland, the MACV commander, rather than to the headquarters of the Army component commander, U.S. Army, Vietnam. These groups included separate advisory elements for the ARVN Airborne Brigade; the Regional and Popular Forces; the Railway Security Advisory Detachment; the Capital Military Region; the Civilian Irregular Defense Group, advisory effort of the 5th Special Forces Group; and each of the four Vietnamese Army corps.

With the introduction of U.S. ground combat forces and the establishment of U.S. Army corps-level headquarters in South Vietnam, modifications in the control of U.S. Army advisory efforts became essential. Following the arrival of the III Marine Amphibious Force in the I Corps Tactical Zone, the advisory group to the I Corps was placed under the operational control of the commanding general of the Marine amphibious force, who was designated the senior adviser to the I Vietnamese Corps commander. The previous senior adviser, an Army colonel, became the deputy senior adviser. In practice this new arrangement caused few changes, since the deputy senior adviser continued to operate much as he had in the past, employing both U.S. Army and Marine Corps officers and enlisted men as advisers. At the headquarters of the III Marine Amphibious Force, the advisory effort thus could not be considered a fully integrated operation within the command structure.

To the south, in the II and III Corps zones of the Vietnamese Army, similar arrangements developed. In the II Corps, after Task Force Alpha had been formed and given operational control of all U.S. Forces, Army advisory personnel remained under MACV's operational control. When the task force was replaced by Field Forces, Vietnam, the Vietnamese II Corps' commanding general expressed annoyance that the senior U.S. Army officer in his area, who was the commanding general of the Field Forces, was not also his senior adviser. Accordingly, in October 1965, General Larsen, the Field Forces' commander, was appointed the senior adviser to the II Corps' commanding general; and-as was the case with the III Marine Amphibious Force-the former senior adviser, also an Army colonel, became the deputy senior adviser. The same arrangements were made in the III Corps zone, with the commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division acting as the senior adviser.

Since no major U.S. Forces were introduced into the IV Corps area, the advisory group there continued under the operational control of the MACV commander, General Westmoreland.

[57]

Control of U.S. Operating Forces

Throughout 1965, control of all U.S. Air Force elements in Vietnam was exercised by the service's component commander. The commanding general of the 2d Air Division, Lieutenant General Joseph H. Moore, was both the component commander and the chief of the U.S. Air Force Advisory Group at MACV headquarters. In May 1965 General Moore was designated General Westmoreland's deputy commander for air operations, a position not to be confused with the Deputy Commander, Military Assistance Command, who had always been an Army general officer.

Air operations against North Vietnam were controlled by the Pacific commander in chief through the commander of the Pacific Air Forces and, in the case of U.S. Navy air forces, through the commander of the Pacific Fleet. Thus General Moore exercised operational control over Air Force units in Southeast Asia as directed by the Pacific Air Forces commander; for air operations over South Vietnam, he was guided by directives from General Westmoreland.

At the beginning of 1965, the component commander for U.S. naval forces in Vietnam was also the chief of MACV's Naval Advisory Group. With the arrival of Marine Corps ground combat forces in March, the commanding general of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade became the naval component commander; the commanding general of the III Marine Amphibious Force assumed this role when his headquarters came ashore in May. This arrangement was modified after the Coastal Surveillance Force (TF 115) was created in July. Both the advisory group and the Coastal Surveillance Force then came under the Chief, Naval Advisory Group, whose title became Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam-Chief, Naval Advisory Group. Thus, General Westmoreland actually had two naval component commanders: one for conventional Navy forces and one for Marine Corps elements.

Except for the Marine Corps command, the arrival of additional U.S. Navy and Air Force troops caused no significant change in the existing command and control structure in Vietnam. With each of these two services organized as a separate component under the Military Assistance Command, the respective commanders reported directly to General Westmoreland for operational matters and through their service chains of command for all other matters.

Throughout 1965, as in 1964, General Westmoreland had subordinate Air Force and Navy component commanders in South Vietnam but acted as his own Army component commander. The Air Force and Navy component commanders had operational con-

[58]

trol over their component forces, as General Westmoreland had over Army forces. This arrangement was compatible with the command and control system of the Vietnamese Army, in which operational control of army forces rested with the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff.

Coordination with Vietnamese and Free World Forces

Before the Free World Military Assistance Forces came to Vietnam, there had been no need for a combined or multinational command. As U.S. And other Free World forces began arriving in South Vietnam in April 1965, however, General Westmoreland recommended establishing a small, combined U.S.-South Vietnamese headquarters, commanded by a U.S. general officer with a Vietnamese deputy or chief of staff. For political reasons, General Westmoreland believed that such a headquarters would have to be introduced gradually and quietly. He also recommended forming an international military security task force as a low-level combined staff in the DA Nang area.

The idea of a combined command appeared to be favored by senior Vietnamese commanders when it was first suggested in April 1965. This attitude, however, was soon replaced by extreme sensitivity to the subject. When this change became apparent, the United States no longer pursued the matter of a combined command, and General Westmoreland withdrew his earlier recommendations, including those concerning the security task force. Instead, U.S. field commanders were instructed to work with Vietnamese commanders on the basis of co-operation and coordination, rather than through a traditional combined command arrangement. To ensure close liaison with the Military Assistance Command, General Westmoreland appointed Brigadier General James L. Collins, Jr., as his special representative to the joint General Staff of the Vietnamese armed forces.

Only in the area of intelligence was there a combined or integrated effort between U.S. And Vietnamese forces. To take the best advantage of the resources of both, four combined intelligence centers were formed: the Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam (CICV); Combined Military Interrogation Center; Combined Document Exploitation Center; and Combined Materiel Exploitation Center. CICV prepared intelligence reports for both U.S. And Vietnamese commands, and the other three exploited enemy prisoners, documents, and materiel. As U.S. Troop strength rose and military operations became more extensive, the number of enemy documents, prisoners, and deserters increased. Consequently, the volume of intelligence data also grew. Pooling the

[59]

resources at the Combined Intelligence Center, therefore, permitted a more efficient use of the limited number of specialists and a faster dissemination of information.

The introduction of Free World Military Assistance Forces into South Vietnam raised the question of their command and control. Two separate arrangements were developed. For troops provided by countries other than the Republic of Korea, operational control rested with the U.S. Military commander in whose area these troops were used. In the case of the South Korean forces, a compromise was worked out between U.S., Korean, and Vietnamese officials by which these forces would remain under their own control, within the limits established by a council to be known as the Free World Military Assistance Council. The council consisted of the MACV commander, the commander of the Republic of Korea Forces, Vietnam, and the chief of the Vietnamese Joint General Staff, who served as chairman.

As early as 1962 the MACV commander had seen the need for a central logistical organization in South Vietnam and had recommended that a U.S. Army logistical command be sent to Vietnam. It was late April 1965, however, before the Secretary of Defense formally approved the establishment of an Army logistical command for Vietnam. On 10 July 1965, the 1st Logistical Command was authorized as a full-strength, type-B command. By the end of the year the command had grown from 5,930 men to more than 22,000. It supported all U.S. And Free World forces south of Chu Lai. The sector to the north was a Navy responsibility.

During the initial buildup phase, communications systems in Vietnam were inadequate to perform the tasks facing the Military Assistance Command. Early in 1965, General Westmoreland, in conjunction with the director of the Defense Communications Agency, Lieutenant General Alfred D. Starbird, requested a consolidation of communications-electronics functions at the MACV level. This proposal was approved by the joint Chiefs of Staff in April 1965; an office of the Defense Communications Agency would be established in Vietnam under the MACV Communications-Electronics Directorate (J-6).

To supplement this joint management, all Army communications-electronics resources in Vietnam were combined in a single command, the 1st Signal Brigade. Established in April 1966, it

[60]

supported the combat signal battalions of the divisions and field forces in each corps area. Additionally, the 1st Signal Brigade operated the many elements of the Defense Communications System in Vietnam. To improve co-ordination and management of communications-electronics assets, the commander of the 1st Signal Brigade also served as the U.S. Army, Vietnam, staff adviser on all matters pertaining to Army communications-electronics.

Command and control in Vietnam has been a matter of controversy since U.S. ground forces were introduced in 1965. Critics have contended that the Vietnam War required clearer lines of command authority and greater subordination of individual service efforts to the control of a single commander. From among their recommended improvements, three significant alternative command structures emerged: a single combined command exercising operational control of all Free World forces, including the South Vietnamese; a separate unified command, directly subordinate to the joint Chiefs of Staff, controlling all U.S. forces in Vietnam; and a separate U.S. Army component command, under the Military Assistance Command, exercising operational control of all U.S. Ground forces in the Vietnam conflict.

A combined command offered significant advantages in major combat operations, was supported by precedents set in World War II and Korea, and applied the principle of unity of command. However, the nature of the Vietnam conflict and the international political situation when the United States initiated combat operations were such that the benefits of a "supreme allied command" would have been canceled out by charges of U.S. colonialism and by difficulties inherent in a future reduction of U.S. Forces A major obstacle to a combined command arrangement was the reluctance of South Vietnam and South Korea to relinquish sovereignty over their armed forces. General Westmoreland recognized these problems. His decision to forgo the advantages of a combined command has been proven sound by subsequent events.

The proponents of a separate unified command contended that eliminating the Commander in Chief, Pacific, from the chain of command would have simplified the direction of the war from Washington and eased the burdens of the commander in Vietnam. This argument was refuted by General Westmoreland, who maintained that the duties performed by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, and the service component commanders allowed him to focus his primary attention on operations in Vietnam, while his

[61]

MACV HEADQUARTERS COMPLEX NEAR TAN SON NHUT, 1969.

lines of communication to the rear were secured and managed by the Pacific Command. A more valid objection to this proposition, however, was the fact that the war in Vietnam could not be considered as an isolated conflict. While the ground fighting was largely confined to South Vietnam, the threat of hostilities elsewhere in Southeast Asia required a contingency planning and response capability available only to the Commander in Chief, Pacific. Therefore, only a division of responsibility between the Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, and the Commander in Chief, Pacific, ensured effective management of the war in South Vietnam and preparedness for other contingencies in Southeast Asia.

Early creation of a U.S. Army component under the Military Assistance Command, with operational control of combat forces and responsibility for fighting the ground war, might have been preferable to existing command arrangements. During 1964 and 1965, however, the advantages of such an arrangement were not evident. U.S. Ground combat forces were originally introduced to provide security for an existing organization. Only after the situa-

[62]

tion deteriorated were these forces compelled to conduct limited offensive operations. General Westmoreland had the choice either to retain the established and, satisfactory method of operation, or to create an additional command headquarters between his MACV headquarters and the combat forces. He decided to retain the existing arrangement and to exercise operational control personally, not only because this method worked but also because his command was designed to match the organization of the Vietnamese armed forces. The absence of a combined command in Vietnam made co-operation and coordination among Free World forces a primary concern. From the U. S. point of view, cooperation and coordination could be maintained effectively only if the Military Assistance Command, like its Vietnamese counterpart the joint General Staff, had full operational control of ground forces, and liaison between the two commanders was as close as possible.

[63]

Return to the Table of Contents

|

Last updated 8 December 2003

|