CHAPTER II

The Military Assistance Command, Vietnam: February 1962 July 1965

The question of establishing a unified military command in South Vietnam was first raised in October 1961. After President Kennedy had bolstered the U.S. commitment in May and again in October, in terms of both personnel and funds, the Military Assistance Advisory Group reorganized to meet the increased demand for field advisers to the South Vietnamese armed forces. General Taylor's mission to Vietnam in October revealed that these measures were inadequate for dealing with the Communist insurgency; therefore, in mid-November the President decided that the United States would assume a growing operational support role in addition to the existing advisory, training, and logistical missions. This decision marked the beginning of a new phase in U.S. support of the South Vietnamese government and its armed forces.

Consequently, the U.S. command structure in Vietnam, which had become overextended even before the new requirements had been established in the President's program, had to be reorganized. In mid-November Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara charged the joint Chiefs of Staff with this task. The new command was to be named the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (USMACV).

At the time, the Military Assistance Advisory Group was the only U.S. military headquarters in South Vietnam. A joint organization, it contained an Army, Navy, and Air Force section, each responsible for advising its counterpart in the Vietnamese armed forces and for assisting the chief of the advisory group in administering the Military Assistance Program. Logistical and administrative support of the Military Assistance Advisory Group was provided through service channels. The chief of the advisory group, General McGarr, however, exercised operational control over all U.S. Army units. For their logistical support, however, the units depended on Lieutenant General Paul W. Caraway, Commanding General, U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands (USARYIS), on Okinawa.

[25]

When the first U.S. Army aviation units arrived in Vietnam in December 1961, the need for logistical support sharply increased. Since no U.S. Army element in South Vietnam could provide the support, General James F. Collins, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, directed the 9th Logistic Command on Okinawa to send a logistic support team to South Vietnam to set up a supply service between the newly arrived aviation units and U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands. On 17 December 1961 an eleven-man team from the 9th, Logistic Command arrived in Vietnam. As the support requirements increased, the team was expanded to 323 men and designated USARYIS Support Group (Provisional). This group formed the nucleus that eventually became the headquarters of U.S. Army, Vietnam-the Army component of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

Meantime, plans for the establishment of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, had gone forward at command headquarters directly concerned with this matter. Planners generally agreed that the Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, should have full responsibility for and authority over all U.S. Military activities and operations in Vietnam. However, regarding the application of this principle, the degree of authority, and the place within the chain of command, the planners took different approaches. The key problem, in retrospect, was just where to find the slot for this new unified command and who would be in immediate control.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff proposed forming a unified command that would report directly to them. The commander would control all U.S. forces in South Vietnam employed in a combined effort against the Viet Cong; he would also be the principal U.S. Military adviser and sole spokesman for American military affairs in Vietnam. Additional responsibilities would include U.S. intelligence operations economic aid relating to counterinsurgency, and any functions of the Military Assistance Advisory Group dealing with improvement of the combat effectiveness of the Vietnamese armed forces. The chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group would retain control of the training mission and would continue to represent -the Commander in Chief, Pacific, in planning and administering the Military Assistance Program. General Collins, Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, agreed with the proposals of the joint Chiefs but recommended in addition that all activities of the Military Assistance Advisory Group come directly under the unified commander in Vietnam.

Admiral Harry D. Felt, Commander in Chief, -Pacific, raised objections to the joint Chiefs' proposal of assigning the U.S. Military

[26]

Assistance Command, Vietnam, directly to the joint Chiefs. In Admiral Felt's view, the Communists were threatening all of Southeast Asia, not just South Vietnam; therefore, a single military effort, co-ordinated by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, was required. Accordingly, he suggested forming a subordinate unified command in Vietnam under the Pacific Command. The Department of State concurred with Admiral Felt's proposal provided the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam would retain over-all authority of U.S. activities in the country.

Deliberations on the structure of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the headquarters' position in the chain of command were complicated by existing contingency plans. Separate sets of plans had been drawn up for possible U.S. unilateral operations on the mainland of Southeast Asia and for combined operations of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) as well. A joint or combined headquarters was provided for in these plans, which was to be headed by the Deputy Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, General Harkins. According to these contingency plans, General Harkins' headquarters was to be under the control of Admiral Felt as Commander in Chief, Pacific.

Because the joint (or combined) field commander in most contingency plans would be the Deputy Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, the headquarters of the U.S. Army, Pacific, had prepared many of these plans and also was to provide the nucleus for the designated operational staffs. For this reason Admiral Felt had decided that the field commander would exercise control of the ground forces as his own Army component commander. This decision was consistent with Army and joint doctrine regarding joint task forces. It followed that this doctrinal precedent would be applied in establishing the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The precedent did not apply to the Air Force and Navy components and their commanders, however, which were to be provided by the Pacific Air Force and Navy commands. The reason was the comparatively small effort required by these two services.

With the approval of President Kennedy and Secretary of Defense McNamara and by direction of the joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Felt established the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, on 8 February 1962, as a subordinate unified command under his control. Lieutenant General Paul D. Harkins, the Deputy Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, who, as the commander-

[27]

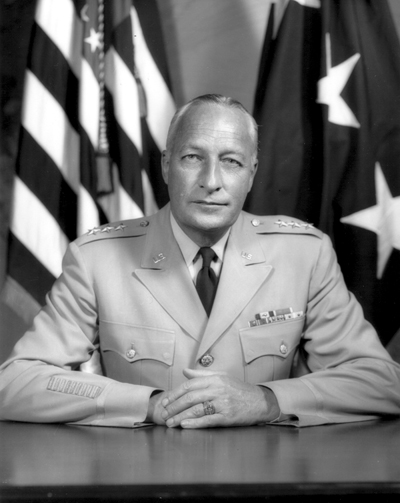

GENERAL HARKINS

designate for the task force headquarters in the event of operations in Southeast Asia, had participated in the planning for such operations, was appointed Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and promoted to general.

In his new position, General Harkins was the senior U.S. Military commander in the Republic of Vietnam and, as such, responsible for U.S. Military policy, operations, and assistance there. General Harkins had the task of advising the Vietnamese government on security, organization, and employment of their military and paramilitary forces. As provided for in the organization of the task force headquarters in the contingency plans, MACV's commander was also his own Army component commander.

With an initial authorized strength of 216 men (113 Army), the Military Assistance Command was envisaged as a temporary headquarters that would be withdrawn once the Viet Cong insurgency was brought under control. In that event, the Military Assistance Advisory Group would be restored to its former position as the principal U.S. headquarters in South Vietnam. For this reason, the advisory group was retained as a separate headquarters under Major General Charles J. Timmes, who had succeeded General McGarr. The advisory group was responsible to the Military Assistance Command for advisory and operational matters and to the Commander in Chief, Pacific, for the administration of the Military Assistance Program. Although general logistic support continued on an individual service basis, the Military Assistance Command was supported by the Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, a small Navy logistical operation.

The temporary character of the new MACV headquarters was further emphasized by the decision initially to limit General Harkins' planning tasks to Vietnam. General Harkins' responsibilities, however, soon expanded when -he was assigned broader planning duties connected with U.S. Unilateral and SEATO contingencies. Admiral Felt directed General Harkins to prepare the support of the Pacific

[28]

Command's plan of action in the event of insurgency and overt aggression in Southeast Asia. In addition, General Harkins was to draft other plans in support of SEATO, thus shifting planning responsibilities in some areas from U.S. Army, Pacific, to the Military Assistance Command. This was a logical trend because General Harkins was still the commander-designate of joint and combined SEATO forces. Before the year was out, such contingency responsibilities were to contribute to a reappraisal of the need and desirability of a separate Army component command under General Harkins' headquarters.

After the Military Assistance Command had been established, the Pacific Air Forces formed the 2d Advance Squadron in Vietnam. The squadron originally functioned as the air component command and later evolved into the air component command headquarters in Vietnam. No immediate steps were taken to establish a naval component command on the Southeast Asia mainland, because one was not needed at the time. Naval duties were handled by the Navy section of the Military Assistance Advisory Group and by Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon.

As the senior U.S. Military commander in Vietnam, General Harkins was directly responsible for all U.S. Military policy, operations, and assistance in Vietnam. He was authorized to discuss both U.S. and Vietnamese military operations directly with President Diem and other Vietnamese leaders. General Harkins also advised the Vietnamese on all matters relative to the security, organization, and use of their armed forces and of counterinsurgency or other paramilitary forces. He had direct access to the Pacific commander in chief and through him to the joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense. Since the U.S. Ambassador was responsible for U.S. political matters and basic policy, General Harkins was to consult him on these subjects; if the two officials disagreed, both were free to submit their respective positions to Washington. The ambassador and the commander were to keep each other fully informed, especially on high-level contacts with the Vietnamese government, on major military plans, and on pending operations.

Command and control of Vietnamese forces remained with Vietnamese commanders, with General Harkins acting as the senior U.S. adviser. The Vietnamese organization provided that the Commander in Chief of the Vietnamese armed forces also be the commander of the Vietnamese Army (ARVN); he was, in every respect, his own Army component commander. Although this arrangement had not been a determining factor in the organization of the Military Assistance Command, the compatibility of

[29]

the two command structures was to be an important influence when the issue of a separate U.S. Army component commander was raised later.

On 15 May 1962 General Harkins' responsibilities broadened when Admiral Felt established the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Thailand (USMACTHAI), and appointed General Harkins its commander. In this capacity General Harkins had essentially the same latitude and authority as in his position as head of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The Thailand command initially consisted of the following groups: the men and equipment of a U.S. joint task force in Thailand, originally deployed as an element of a SEATO exercise and later held there because of Communist activity in Laos; the Joint U.S. Military Assistance Group, Thailand; and other U.S. Military elements deployed to Thailand. Later in 1962, Major General Theodore J. Conway, Chief, Joint U.S. Military Assistance Group, Thailand, was designated to serve concurrently as General Harkins' deputy in Thailand. A staff' was formed to assist General Conway with these additional duties. Administrative support of units and elements in Thailand remained the responsibility of the separate services. Thus, while directing U.S. Military activities in Vietnam, General Harkins also took charge in Thailand of the Military Assistance Program, the planning and support of Army activities, and contingency plans and exercises.

The Military Assistance Advisory Group

During the conferences that led to the establishment of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, the question of how to fit the existing Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) into the new command structure was discussed. The planners, concerned about this problem, were aware that the Military Assistance Command, at least temporarily, would replace the advisory group as the principal U.S. Military headquarters in Vietnam and would also absorb other functions that the advisory group had been charged with in the past. In retaining both headquarters, a certain amount of duplication would be unavoidable. Although abolishing the advisory group as a separate organization would have avoided this duplication, MAAG's traditional role and its working relationship with the Vietnamese armed forces, established over a ten-year period, would have been sacrificed, together with MAAG's institutional expertise, which the new command had yet to acquire.

[30]

For these reasons, the Military Assistance Advisory Group was retained. The MAAG chief, General Timmes, continued to exercise control over U.S. Army units. He also was charged with the development and administration of the Military Assistance Program and the day-to-day advisory and training effort for the Vietnamese armed forces.

The U.S. Army's chain of command arrangements were not changed by the establishment of the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam. The Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, General Collins, continued to provide administrative and logistical support to U.S. Army units in Vietnam through Headquarters, U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands. General Harkins had operational control of Army units, but he delegated the authority to General Timmes. Thus, even though functions of the Military Assistance Command and the advisory group technically overlapped, the duplication in some areas of responsibility did not interfere with U.S. assistance and advisory activities in Vietnam.

U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam

In March 1962 Headquarters, U.S. Army, Pacific, issued a letter of instruction that removed the "provisional" designation from the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, attached it to U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, for administrative and logistical support, and made its commanding officer the deputy Army component commander under the Military Assistance Command. In turn, all U.S. Army units in Vietnam (excluding advisory attachments) were assigned to the Army Support Group for administrative and logistical needs. Although the support group was under the operational control of the Military Assistance Command, it was also required to support U.S. Army, Pacific, in carrying out its missions. In effect, this arrangement removed the support group from the command of U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, even though the group continued to depend on U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, for logistical and administrative support. The twofold mission of the group was to support combat operations and to provide the nucleus for a type-B logistical command headquarters that would direct combat support units in Vietnam under existing contingency plans.

In July 1962 the Commander in Chief, U.S. Army, Pacific, General Collins, corrected the dual arrangement by permanently assigning the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, to U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands. (Chart 4) This command relationship was to continue, until 1965, when the successor to the group, U.S. Army,

[31]

CHART 4-U.S. COMMAND RELATIONSHIPS IN VIETNAM, 1962

Source: Department of Army Management Review Team, Review and Analysis of the Army Command and Control Structure in Vietnam, Vol. II (Washington: 29 July 1968), p. AV-12.

Vietnam, was placed directly under U.S. Army, Pacific, thereby eliminating the Ryukyu Islands headquarters from the chain of command. Throughout the entire period, the support group remained under the operational control of the Military Assistance Command. The commander of the support group, although still the deputy Army component commander of the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam, became responsible for executing the plans

[32]

and directives of General Caraway in the Ryukyus as well as for carrying out General Collins' missions in South Vietnam. Operational control of most Army units, particularly aviation companies, rested with General Timmes, chief of the advisory group in Vietnam, to whom General Harkins had delegated this authority. Under this arrangement, Army strength rose from 948 to 7,885 men during 1962.

Control of Army aviation assets at this time illustrates the multiple lines of responsibility in Vietnam. Since General Timmes had operational control of Army aviation units, the senior adviser assigned to a Vietnamese Army corps could directly request U.S. Army aviation support. For example, the Vietnamese corps commander could initiate and plan a helicopter operation. The adviser assigned to the corps would formally transmit a request to the commanding officer of a U.S. Army helicopter company for execution. Actual planning for such an operation thus involved the Vietnamese corps commander and his staff, the Military Assistance Advisory Group's representative, and the commander of the helicopter company. Issues which could not be resolved locally between the adviser and the commanding officer of the helicopter unit were referred to General Harkins through appropriate channels. Army aviation unit commanders, therefore, had to deal with and satisfy, on a daily basis, the Vietnamese Army, the Military Assistance Advisory Group, the Military Assistance Command, and the U.S. Army Support Group: The support group, in turn, had to carry out responsibilities to the U.S. Army, Pacific; U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands; and the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam.

Concern over the conflicting command and control arrangements established by the various contingency plans resulted in a series of conferences in the fall of 1962 to examine the situation and, in particular, to study the need for a separate Army component commander. The responsibilities assigned to General Harkins under various contingency situations prompted him to recommend alternate command arrangements for Vietnam. His recommendation led to counterproposals by the joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Felt, and the service components. Strongly influenced by the Laotian crisis in 1962, General Harkins proposed that a ground component command headquarters, separate from the joint or combined higher headquarters, be established for all unilateral and SEATO contingency plans for operations in Southeast Asia. If these plans for Vietnam, Thailand, or Laos were to be imple-

[33]

mented, a combat-capable Army component commander and staff should be available to conduct the land war. Although the U.S. Army Support Group was the Army component command within the Military Assistance Command at the time, its functions were limited to logistical and administrative matters and excluded operational matters, which were the concern of the chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group. Neither headquarters could qualify as a true Army ground component command.

In commenting on General Harkins' proposal, General Collins indicated that a headquarters like the Army corps headquarters provided in contingency plans would be appropriate for the conduct of ground operations. The corps headquarters would also be able to perform the other duties of a ground component command under joint (Military Assistance Command) or combined (SEATO) direction, at least during the first stages of an operation. General Collins emphasized, however, that his proposal would be valid only if the joint or combined commander was a U.S. Army general officer.

General Harkins' proposal also dealt with the subject of the command structure in Thailand. He suggested that Army units in Thailand be placed directly under the deputy commander of the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, who would then be the Army component commander there. Admiral Felt, however, believed that the operations of the Army component command in Thailand should remain within Army (U.S. Army, Pacific) channels rather than being vested in a joint headquarters; he also indicated that General Harkins should be his own ground component commander. Finally, Admiral Felt recommended new arrangements for Thailand that would relieve General Harkins of all responsibilities in Thailand and Laos.

These issues were considered at a meeting held in Hawaii in October 1962. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara decided that General Harkins should retain his responsibilities in Thailand and his title of Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Thailand (actually, the title decided upon at the meeting was Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Thailand). The chief of the Military Assistance Group in Thailand would be the deputy commander of the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, under General Harkins and would have operational control over all U.S. forces in Thailand. Logistic and administrative support of the forces there would remain the responsibility of the service components of the Pacific Command. A small joint staff of the Military Assistance Command would remain

[34]

in Thailand, primarily for planning purposes. These arrangements became effective on 30 October 1962.

General Harkins raised other command questions at this conference, some of which were discussed but not settled. He pointed out, for example, that the component commands in Vietnam were neither organized nor staffed to carry out the planning, operational, and administrative tasks normally performed by component commands. In Vietnam the component commanders had had primarily administrative and logistical duties. General Harkins, therefore, suggested that the component headquarters be reorganized and strengthened, so that they could assume their full share of command functions in Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos, if unilateral or SEATO plans were ever implemented.

The most significant result of the discussions about component commands was that the Pacific Air Forces' 2d Advance Squadron, the largest U.S. Air Force headquarters in Southeast Asia outside the Philippines, was expanded and redesignated 2d Air Division. The division controlled most operations of the Pacific Air Forces of the mainland of Southeast Asia. The command channel originated with the Commander in Chief, Pacific, went to the commander of the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam and Thailand, and then to the commanding general of the 2d Air Division; the Pacific Air Forces provided administrative and logistical support. General Harkins thus acquired a responsive Air Force component command. For certain air operations over the Southeast Asia mainland outside the operational area of General Harkins' command, however, the 2d Air Division continued to report to the commander in chief of the Pacific Air Forces, and through him to Admiral Felt. The decision limited General Harkins' authority over, and responsibility for, air operations other than those concerned with direct support and assistance to Vietnamese forces.

Since naval activity in Southeast Asia had not significantly increased, a naval component command was not established.

During 1962 the strength of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam rose from about 1,000 to over 11,000 men. Each service was responsible for its own logistic support, although Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, continued to provide logistical and administrative support to General Harkins' headquarters and countrywide support to all advisory personnel, including the Army's. Support for other Army forces in Vietnam came from Okinawa and the continental United States. Logistic operations were thus decentralized with only limited over-all co-ordination; common-user arrangements for major logistic items had not yet been developed.

[35]

Deputy Army Component Commander

Realizing that the command and control arrangements governing Army combat service support in Vietnam should be refined, General Collins acted to modify them in March 1963. With the concurrence of the Military Assistance Command and the approval of Admiral Felt, General Collins issued a letter of instruction in August 1963 appointing General Harkins the Army component commander for current operations in Vietnam. In addition, Brigadier General Joseph W. Stilwell, Commanding General, U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam, was designated deputy Army component commander of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. This change had the effect of channeling to General Stilwell most problems peculiar to the Army. General Harkins, as the head of the Military Assistance Command, had operational control over Army units; General Stilwell, as his deputy, exercised command less operational control of the units and continued to provide combat service support.

These changes were minor since, in practice, responsibilities had already been divided along these lines. The new instructions did clarify command relationships between the Military Assistance Command, the advisory group, the support group, and U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, concerning control over Army advisers and organizations in Vietnam. Furthermore, the new arrangements were aligned with Admiral Felt's concept of a command structure in Vietnam. Additional advantages included improved control of Army men and equipment needed for counterinsurgency operations, and better coordination between the Military Assistance Command and the Vietnamese Army because of the similarity between the two organizations.

The South Vietnamese Joint General Staff, like the Military Assistance Command, had direct operational control over Vietnamese Army forces, while the Vietnamese Army's headquarters exercised command less operational control, performing primarily support and training missions. Under the revised command arrangements, the U.S. Army Support Group was responsible for those component command missions and functions pertaining to Army activities in South Vietnam, particularly combat service support. U.S. Army, Ryukyu Islands, continued to exercise command less operational control over the support group.

In addition to the duties carried over from the previous command structure; the support group became responsible for coordinating, through the Military Assistance Command, Vietnamese assistance in providing security for U.S. Army organizations in

[36]

Vietnam. The support group also was to provide logistical support for units of the U.S. Army Security Agency in South Vietnam, common supply support to other U.S. armed services in accordance with locally approved interservice support agreements, a base from which to expand U.S. Army activities in Vietnam, and command elements as needed to direct and support additional U.S. Army units arriving in Vietnam. Finally, the support group was to undertake long-range base development planning. It was to advise Army headquarters both in the Ryukyus and in Hawaii of all Army component command functions being delegated to General Stilwell by General Harkins.

Throughout 1963 the duties of the U.S. Army Support Group steadily increased, particularly those pertaining to combat support activities and logistic requirements. During the year, the U.S. buildup continued, especially in aviation, communications, intelligence, special warfare, and logistic units, reaching a total of 17,068 men, of which 10, 916 were Army. Because of this expansion, General Stilwell late in 1963 proposed that the name of the support group be changed to U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam. General Harkins concurred and General Collins and Admiral Felt approved the redesignation, providing the change in no way altered the group's existing or potential roles and missions. The new designation went into effect on 1 March 1964.

In October 1962 Admiral Felt assigned General Harkins the task of organizing and directing an airlift system in Southeast Asia. The U.S. Air Force's 315th Air Division in Japan was to exercise flight control over all aircraft in the system and supply a combat cargo group to provide actual airlift. General Harkins placed the cargo group under the 2d Air Division to satisfy the requirement of the Unified Action Armed Forces doctrine, which specified that component commanders retain control of units of their own service.

The requirements of the Unified Action Armed Forces, as well as Admiral Felt's directives, raised command problems between the U.S. Army and Air Force. The problems centered around the functions of the air operations centers in Vietnam and the use of Army Caribou aircraft. The Air Force interpreted the term "air" as embracing all aircraft and wanted all aviation units, including those from the Army, to report to Air Force control facilities. Army commanders hell that Army aviation elements should be controlled by the ground commander.

[37]

A directive of 18 August 1962 from General Harkins stated that the air operations center, with the Air Force component commander as co-ordinator, was to advise on command decisions and pass them on to all forces concerned. Army commanders felt that this policy was inconsistent with the operational responsibility of the senior U.S. Army adviser to each Vietnamese Army corps and that it violated the principle of unity of command. The Air Force component commander, on the other hand, pointed out that the corps' senior advisers lacked an air operations and planning staff and could not exercise effective control of supporting aviation units. Under these circumstances, the Air Force component was the proper agency to assume air control; Army interests could be served by Army representation at corps air support operations centers. Since Admiral Felt had directed the Air Force component commander to co-ordinate operations of all U.S. aviation units through the tactical air control system, the Army lost direct control of its aviation units.

Reorganization of MACV Headquarters (May 1964)

With the expansion of U.S. Military activities in Vietnam, conflicting and overlapping roles of U.S. headquarters in Vietnam-especially of the Military Assistance Advisory Group and the Military Assistance Command-became more apparent. Thus in early 1964 the reorganization of the American command structure again came under high-level review. Various proposals focused primarily on the consolidation of the headquarters of both the advisory group and the Military Assistance Command but touched also on such questions as the component command structure and MACV's continuation as a subordinate unified command.

Consolidation of the two headquarters had been considered when the Military Assistance Command was first activated in February 1962. At that time, it was decided that the command should set the policy and supervise the conduct of the counterinsurgency effort in Vietnam, but not become involved with the details of planning the Military Assistance Program, nor with the day-to-day advisory effort for the Vietnamese armed forces. These routine functions were to remain the responsibility of the advisory group. Moreover, the Military Assistance Command had originally been organized as a temporary headquarters.

Almost from the beginning some duplication of effort between the two headquarters had been unavoidable. Since the advisory group was under MACV's operational control, the command had review authority over the group's activities. Unorthodox command

[38]

MAIN ENTRANCE TO MACV I HEADQUARTERS LOCATED AT 137 PASTEUR, 1962.

channels resulted, funding for some activities became complicated, and advisers in the field with Vietnamese units felt they served two masters. As the tactical situation deteriorated, it became more and more difficult to distinguish between the respective missions, functions, and responsibilities of the two headquarters. Vague and overlapping channels also existed in the Vietnamese armed forces and in the government of Vietnam, and the management of military and nonmilitary units available to assist the Vietnamese Army suffered. Finally, duplication also occurred between MACV and MAAG headquarters and the service components, especially in providing logistical and administrative support to advisory detachments in the field.

As early as September 1962 General Harkins proposed that all advisory group functions except those related to the Military Assistance Program be transferred to the component commanders of the Military Assistance Command, and that the headquarters of the advisory group become a staff division of MACV headquarters. This proposal was discussed with the Commander in Chief, Pacific, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff' several times during 1962 anal 1963.

[39]

Admiral Felt opposed the plan primarily because he did not want MACV headquarters to become bogged down in the details of the Military Assistance Program and day-to-day advisory activities.

Following discussions with Secretary McNamara and General Earle G. Wheeler, the Army Chief of Staff, in March 1964 in Vietnam, General Harkins on 12 March submitted a new proposal for consolidating the Military Assistance Command and the advisory group. General Harkins' primary objective was to eliminate the advisory group as an intervening command in the U.S. training and advisory effort, thus enabling the Military Assistance Command to manage U.S. military programs and resources more directly, in conformity with the requirements of the South Vietnamese government's new Chien Thang National Pacification Plan. Noting that 65 percent of the U.S. Military effort involved Army personnel or units, and that 95 percent of the counterinsurgency effort by the Vietnamese armed forces was carried out by their army, General Harkins requested operational control over all Army advisory activities. Under his proposed reorganization, ~MACV headquarters essentially would be a U.S. Army specified command, rather than a subordinate unified command under the Commander in Chief, Pacific. General Harkins wanted to retain a joint staff, although that staff would be heavily weighted with U.S. Army positions. At the same time, General Harkins would be his own Army component commander. All Army administrative and logistical support activities previously handled by the Army section of the Military Assistance Advisory Group would pass to a single headquarters, U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam, which had shared such responsibilities with the section. With the elimination of the Army section of the advisory group, the Army advisory program would become General Harkins' direct responsibility.

Under General Harkins' proposal, all other advisory activities of the individual services would become subordinate to their respective component commands. U.S. Navy and Marine Corps advisory activities would be handled by the Naval Advisory Group, which for all practical purposes was a redesignation of the Navy section of the Military Assistance Advisory Group. The chief of the Naval Advisory Group would be the Navy component commander of the Military Assistance Command and exercise direct operational control over Navy and Marine Corps advisory detachments. The Commanding General, 2d Air Division, would be MACV's Air Force component commander. The Air Force section of the Military Assistance Advisory Group was to pass to the operational control of the 2d Air Division and become the Air Force Advisory Group,

[40]

which in turn was to exercise direct operational control over Air, Force advisory units. Air Force responsibilities in the Military Assistance Program, however, would be retained by MACV headquarters. These steps would place all Navy and most Air Force activities under single- commanders directly responsible to General Harkins and would eliminate the Military Assistance Advisory Group as an intervening command in the U.S. Training and advisory mission in South Vietnam: After the advisory group--was eliminated, the Military Assistance Program would come under MACV headquarters. General Harkins' plan also called for combining the special staff sections of the Military Assistance Command and the Military Assistance Advisory Group.

As the organization for the Military Assistance Program (MAP) ultimately developed within MACV headquarters, two staff directorates were established: the MAP Directorate and the Director of Army MAP Logistics. The former was a general policy, planning, and programming agency, and the latter assumed MAP logistic activities on a technical service basis.

In his comments on General Harkins' proposals to the joint Chiefs, the new Commander in Chief, Pacific, Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, Jr., who assumed command in February 1964, reiterated his predecessor's opposition to the merger of the two headquarters. He objected to the reorganization because it would tie the MACV commander to the details of the Military Assistance Program and the various advisory activities and prevent key members of the MACV staff from assuming positions in contingency operations. Admiral Sharp believed that establishing separate Naval and Air Force advisory groups would be tantamount to setting up two new uniservice Military Assistance Advisory Groups. He rejected General Harkins' basic concept-MACV as a specified Army command reporting to the joint Chiefs, rather than as a subordinate unified command reporting to the Commander in Chief, Pacific-in the belief that the unified effort in Vietnam needed to be strengthened, not diluted. Admiral Sharp also noted that the proposed reorganization would greatly increase General Harkins' span of control-from five major subordinate elements to twelve or more-thereby multiplying command problems instead of reducing them.

Admiral Sharp proposed a more limited reorganization to the joint Chiefs. He recommended that field advisers in Vietnam come under the control of the Military Assistance Command instead of the Military Assistance Advisory Group, which could then be reduced. The advisory group could continue to handle all MAP activities, including detailed planning and programming, and to

[41]

GENERAL WESTMORELAND

provide advisers to units-such as depots, schools, training centers, and administrative facilities-not directly involved in combat operations.

Early in April 1964 the joint Chiefs approved the reorganization essentially as proposed by General Harkins. The did not, however, agree with his implied suggestion that MACV headquarters become an Army specified command, although they recognized that the headquarters would be heavily staffed with Army personnel. Finally, effective 15 May 1964, the Military Assistance Advisory Group was formally dissolved and the reorganized MACV headquarters was authorized. About a month later, on 20 June 1964, General William C. Westmoreland assumed command of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

Another organizational issue concerned research, development, testing, and evaluation activities in South Vietnam. Admiral Felt had proposed a consolidation of these operations in 1963, and in February 1964 the joint Chiefs established the joint Research and Test Activity. This organization would control and supervise the several previously separate research and development agencies: the Department of Defense's Advanced Research Projects Agency Research and Development Field Unit; the U.S. Army Concept Team in Vietnam; the Air Force Test Unit, Vietnam; and the Joint Operations Evaluation Group, Vietnam. With the reorganization of MACV headquarters, the joint Research and Test Activity acted as a joint agency under the operational control of the MACV commander. The Commander in Chief, Pacific, however, retained general responsibility for all research, development, testing, evaluation, and combat development activities throughout the Pacific Command.

The logistic system in Vietnam had failed to keep pace with rapidly expanding and increasingly complex support requirements. Army units under the operational control of the Military Assistance Command continued to receive combat service support from the

[42]

U.S. Army Support Command. The Navy's Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, established in 1962, continued to support MACV headquarters. Before the Military Assistance Advisory Group was dissolved, the support command assumed some of the logistic functions performed by the Army section, while the Navy's Support Activity in Saigon continued to provide countrywide support for Army advisory personnel.

Although U.S. strength in Vietnam grew from about 16,000 men (10,716 Army) to about 23,300 (16,000 Army) in 1964, logistic support operations were highly fragmented. Support for the U.S. Army came mainly from Okinawa and the continental United States; for the Marine Corps, from Japan and Okinawa; for the Navy, from the Philippines and Hawaii; and for the Air Force, largely from the Philippines. For example, there was no single logistic organization in Vietnam able to repair common-user items, such as vehicles, small arms, radios, generators, and office equipment. Transportation operations presented a particularly complex problem because personnel and equipment movements came under several transportation agencies. The search for ways to improve the logistic situation led to the next major change in the Army's command structure.

The major deficiency in logistic support operations in South Vietnam was the absence of an integrated logistic system. Although the Navy furnished logistic support to unified commands under the Pacific Command-a responsibility which Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, discharged for MACV headquarters-the Navy had neither the organizations nor the equipment to provide the growing level and diversity of support required. The Navy's support activity had been established in 1962 with duties limited to peacetime functions by the situation then existing in Vietnam, but it was not prepared to handle the kind and volume of support needed after 1963.

In addition to the support activity headquarters, the Navy was in charge of its own logistic system to support Navy personnel. Most Air Force logistic needs were filled by the 2d Air Division, and the Army was supplied by the U.S. Army Support Group, Vietnam. Other smaller military logistic support systems, as well as those of nonmilitary U.S. government agencies, were also operating in Vietnam. Finally, there was a commercial logistic agency operated by suppliers of petroleum, oil, and lubricants, who delivered their products to U.S. and Vietnamese forces under various civilian contracts. In all, fifteen separate logistic systems supported operations in Vietnam, supplying more than 150 locations where Americans were stationed. The logistic system reflected a lack of advance

[43]

planning. The absence of a central logistic agency resulted in confusion that could be remedied only by organizational changes.

Although various improvements in the logistic organization had been considered previously, it was early 1964 before the principal commanders and service chiefs involved agreed that an Army logistic command was needed in Vietnam. When the U.S. Army Support Group was created in 1962, one of its functions was to provide the nucleus for a type-B Army logistic command headquarters for contingency plans. When General Stilwell, the chief of the support group, also became the deputy Army component commander, his responsibilities increased to a point where his headquarters could not be expected to assume the additional duties of a logistic command. To solve this problem, a separate Army logistic command, deployed to Vietnam, was proposed.

Following a period of about three months, during which the strength, source of personnel, troop lists, and other related issues were worked out by the various headquarters concerned, Secretary of Defense McNamara approved the deployment of the 1st Logistical Command from the United States. An engineer group and the 1st Logistical Command were assigned to General Stilwell's command, which had been elevated from support group status to the U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam, on 1 March 1964.

The 1st Logistical Command was originally established as a reduced type-A command. This meant it could command an integrated organization with a total strength of 9,000-15,000 men and could provide an organizational structure and a nucleus of trained logisticians and administrative personnel to support a major independent force of one reinforced division, approximately 30,000 men. Because of the U.S. buildup of forces in Vietnam, the 1st Logistical Command, on 10 July 1965, was authorized as a type-B command, one step up from type A, with a strength of 5,930 men. In accordance with its table of organization and equipment, this type of command could be augmented to a strength of 35,00060,000 men in order to support an independent corps command, approximately 100,000 troops. The initial mission of the 1st Logistical Command was to provide support for all U.S. Army forces. As it, grew, the command was gradually to take over the missions of Headquarters, Support Activity, Saigon, and assume responsibility on a phased basis for common-user supply services to all organizations of the U.S. And Free World Military Assistance Forces south

[44]

of Chu Lai. The Navy was assigned the same task in the sector north of Chu Lai as far as the Demilitarized Zone.

By the end of 1965, in order to support the large number of U.S. combat elements introduced during the year, the strength of the 1st Logistical Command had increased to more than 22,000 men-over four times the projected estimate made a year earlier. Headquarters strength also grew from 159 men to 491. Toward the end of 1965 the 1st Logistical Command was mainly concerned with setting up subordinate logistic support areas at Qni Nhon, Nha Trang, and Vung Tau, and with developing the logistic depot and port complex at Cam Ranh Bay. The magnitude of the effort needed to establish this logistic base prevented the development of a common-item supply system and the shift of support activity functions to the Army.

Beginning in March 1965, combat elements of the U.S. Marine Corps were deployed in the Da Nang area. When the III Marine Amphibious Force was established at DA Nang on 6 May, its commanding general, Major General William R. Collins, USMC, was designated the Naval component commander, a position previously held by the chief of the Naval Advisory Group, MACV. Later in the year, Rear Admiral Norvell G. Ward was appointed Chief, Naval Advisory Group, MACV. Since Admiral Ward, and not General Collins, directed the Navy's advisory effort as well as its coastal surveillance force, General Westmoreland, for all practical purposes, had two Naval component commanders for most of 1965.

On 25 June Major General Joseph H. Moore, USAF, who commanded the 2d Air Division and also served as the Air Force component commander, was made General Westmoreland's deputy commander for air operations at the grade of lieutenant general.

Although Air Force and Navy advisers operated under their component commanders-subject to general directives from the MACV commander-there was no central direction of the Army's advisory effort. Army advisory elements were widely dispersed. They served each of the four corps tactical zones of the Vietnamese Army, the ARVN Airborne Brigade, the Capital Military Region, and the Civilian Irregular Defense Group. In all, nine Army advisory groups reported directly to General Westmoreland.

On 10 July 1965, General Westmoreland's responsibility for military activities outside Vietnam was lessened when the positions of MACV commander and MACTHAI commander were separated. This action resulted from more than a year of discussions at

[45]

the headquarters of the Pacific Command and at the Department of Defense. Military considerations-that Southeast Asia was a strategic entity and that fragmentation of command responsibilities would violate the basic principle of unity of command-tended to support continued adherence to a central command. Political considerations, on the other hand, such as Thailand's complaint that U.S. forces in Thailand were commanded from Saigon, suggested separation. The case for separation prevailed, and Major General Ernest F. Easterbrook, who was at the time both the deputy commander of MACTHAI and the chief of the Military Assistance Group in Thailand, was appointed Commander, Military Assistance Command, Thailand. General Easterbrook retained his position as chief of the assistance group in Thailand, and by the end of 1965 both headquarters were consolidated into one.

In early June 1965 a contingent of Australian and New Zealand forces arrived in Vietnam. Both were placed under General Westmoreland's operational control and attached to the 173d Airborne Brigade. Thus the precedent of placing Free World forces under the operational control of General Westmoreland was established and, later, followed by other nations. At no time, however, did General Westmoreland exercise operational control over the South Vietnamese armed forces.

The major buildup of U.S. Army combat forces and support activities that had begun early in 1965 required yet another reorganization. An Army headquarters was needed in Vietnam with capabilities far exceeding those of a logistical command. The issue of a separate Army component command was revived and eventually led to the decision to upgrade the U.S. Army Support Command and establish U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV), in July 1965.

[46]

Return to the Table of Contents

|

Last updated 8 December 2003

|