FIRST SATELLITE TERMINAL, BA QUEO, NEAR SAIGON. This station linked Vietnam with Hawaii in first use of satellite communications in a combat zone.

CHAPTER II

Military Intensifies Communications

Activities, 1964-1965

Before the 39th Signal Battalion could make much progress toward training Vietnamese communications personnel, optimistic plans looking toward an early military solution of the war were wrecked by current events. In November 1963, South Vietnam's first president, Ngo Dinh Diem, was assassinated and his government overthrown. There followed a series of rapidly changing governments, producing a state of disorganization that seriously weakened the South Vietnamese efforts against the Viet Cong. Meanwhile, in early 1964, Hanoi decided to infiltrate North Vietnamese Regular Army troops into South Vietnam to defeat the disorganized and confused South Vietnamese. Hanoi also started to equip the Viet Cong with modern automatic weapons.

The Tonkin Gulf incidents of early August 1964 marked the first direct engagements between North Vietnamese and U.S. forces and, according to General William C. Westmoreland, "represented a crucial psychological turning point in the course of the Vietnam War." By December 1964 the North Vietnamese had infiltrated no less than 12,000 troops, including a North Vietnamese Army regiment, into South Vietnam. At the same time a Viet Cong division had been organized and was engaged in combat operations. In order to bolster the faltering South Vietnamese forces, the United States deployed additional advisers and support units. The Republic of South Vietnam forces were increased by 117,000 men during 1964, attaining a strength of over 514,000. Their effectiveness, however, decreased markedly. Through the last half of that year US troop strength increased rapidly. The number was approximately 16,000 in June of 1964 when General Westmoreland assumed the responsibilities of Commander, United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. By the year's end, US troops in Vietnam numbered about 23,000.

[17]

The inadequacy and unreliability of the meager radio circuits linking Vietnam with Hawaii and Washington became painfully evident during the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incidents. In the first week of August the engagement of US Navy vessels by North Vietnamese torpedo boats resulted in a flurry of telephone calls and messages between Saigon and Washington. The long-haul high-frequency radio circuits, hampered by severe sunspot activity and occasional transmitter failure in Saigon, were simply not capable of carrying the load. The WET WASH cable project, which would subsequently bring highly reliable services into Southeast Asia, was not yet complete.

An experimental satellite ground terminal, with an operating team under Warrant Officer Jack H. Inman, was rushed to Vietnam to bolster communications capabilities. The terminal, which provided one telephone and one teletype circuit to Hawaii, became operational in late August 1964. Signals were relayed from Saigon to Hawaii through a communications satellite launched into a stationary orbit some 22,000 statute miles above the Pacific Ocean. This experimental synchronous communications satellite system, dubbed SYNCOM, was the first use of satellite communications in a combat zone. The satellite ground terminal in Vietnam, which was operated by the US Army's Strategic Communications Command, provided the earliest reliable communications of high quality into and out of Vietnam.

The SYNCOM satellite communications service was improved in October 1964 with a newer terminal that provided one telephone and sixteen message circuits. These "space age" communications means immediately proved their worth. The Command History, 1964, of the United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, states: "Since October the . . . [satellite terminal] has handled a remarkable volume of operational traffic." And further: "It appears that satellite communications are here to stay and will increase MACV [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam] capability in the future."

System Problems, Further Plans, and Control Matters

Communications deficiencies within Vietnam became more apparent as the hard-pressed signalmen struggled to provide the communications service required by the new buildup. As early as mid1963 it was recognized that the single 72-channel tropospheric scatter link between Saigon and Nha Trang did not have sufficient

[18]

FIRST SATELLITE TERMINAL, BA QUEO, NEAR SAIGON. This station linked Vietnam with Hawaii in first use of satellite communications in a combat zone.

capacity to pass the required traffic from Nha Trang, where two other 72-channel systems from Pleiku and Qui Nhon converged for interconnections to the south. The BACK PORCH sites had been chosen as a compromise between the ease of maintaining site protection and securing the radio propagation characteristics required for operation. As a result some links performed poorly, the poorest link being the saturated one between Saigon and Nha Trang.

Another shortcoming of the long-lines systems which steadily became more apparent was the lack of adequate facilities to control, test, and interconnect circuits, that is, the lack of technical control facilities at the channel breakout or switch locations such as Nha Trang, Pleiku, and Qui Nhon. Colonel Thomas W. Riley, Jr., who was the US Army, Vietnam, Signal Officer in 1965, later recalled: "It was ironical that such big costly refined . . . links as . . . provided at Pleiku-involving a . . . [multimillion dollar] installation connecting Nha Trang to the east with . . . [Ubon, Thailand] to the west-came together at Pleiku in a shed." As

[19]

As a result of both these technical problems and the requirements generated by the buildup, the Commander in Chief, Pacific, by October 1964 had validated requirements to the joint Chiefs of Staff for additional communications service. These requirements became known as Phase I of the Integrated Wideband Communications System. A wideband communications system as described in the Military Assistance Command Vietnam History of 1965 is "a communications system which provides numerous channels of communication on a highly reliable basis; included are multichannel telephone cable, troposcatter, and multi-channel line of sight radio systems such as microwave."

This communications project would include the establishment of a BACK PORCH type of system in Thailand. The Vietnam portion as visualized by the planners would provide support for up to 40,000 US troops by upgrading the existing fixed tropospheric scatter communications; by improving service in the Saigon area; by establishing an additional link north to bypass the system between Saigon and Nha Trang, extending additional channels north from the Saigon area and from the Da Nang area still further north to Phu Bai; and by installing adequate technical control facilities throughout the system.

By December 1964 the Defense Communications Agency had prepared a plan and forwarded it through the joint Chiefs of Staff

[20]

The Department of Defense, while the plan was being studied, decided to use permanent, fixed installations rather than large transportable shelters for the system. This decision would require construction of buildings and other facilities in Southeast Asia to house the equipment. The decision was made on the basis that time was the critical factor-the system was needed right thenand the contractors were promising that the system could be operational one year after contract award if commercial equipment and prefabricated buildings were used. The use of "transportables," that is, commercial equipment installed in large vans similar to the equipment used on BACK PORCH, was considered; it was estimated, however, that transportables would require more time to manufacture and put into operation than a fixed system and that they would be more costly.

The plan called for the system to be operational by 1 December 1965, an early date that proved altogether too optimistic. For example, the plan was not approved for contracting action until the Department of Defense approved it as a "Telecommunications Program Objective" in August 1965. The US Army, which was designated as the contracting agency, awarded the contract for the Vietnam portion of the system to Page Communications Engineers, Inc., in September 1965. The system would be operated by the US Army Strategic; Communications Command, which was originally activated on I April 1962 by combining the US Army Signal Engineering Agency and the US Army Communications Agency. This was in line with its mission as the Army's single operator of those portions of the worldwide Defense Communications System assigned as an Army responsibility.

Organizational and control arrangements changed during this period. The US Army Support Croup, Vietnam, was redesignated as the US Army Support Command, Vietnam, in March 1964, when the dual-hat status of the Army component command signal officer also changed. Previously, he had served both as the Army Support Group Signal Officer and as the Commanding Officer, 39th Signal Battalion. But following the reorganization, the positions were allocated separately; according to personnel lists of

[21]

Also in 1964 the command and control arrangements for the big Strategic Army Communications Station, Vietnam, were affected by the creation and expansion of the US Army Strategic Communications Command and its Pacific subcommand headquartered in Hawaii. In November 1964 the station was redesignated Strategic Communications Facility, Vietnam, and at about the same time control of the facility passed from US Army Support Command, Vietnam, to US Army Strategic Communications Command, Pacific. These changes in 1964 marked the beginning of a division of control over Army communications in Vietnam between the Army Strategic Communications Command and the Army component command signal troops.

By the spring of 1965 the combat situation had deteriorated further. The casualties of the South Vietnamese Army were mounting to the point that the equivalent of almost one infantry battalion a week was being lost. In March the United States sent Army airborne and Marine combat troops to defend US air bases in Vietnam against enemy attack. In order to support these forces, it was necessary to deploy a logistical command and other combat support troops. An additional signal unit, the 41st Signal Battalion, and Headquarters, 2d Signal Group, were alerted for movement to Vietnam.

By mid-1965 it had been decided to commit substantial numbers of US fighting troops along with other combat support organizations. The emphasis was on the introduction of infantry, armor, and artillery elements. As General Westmoreland relates in his report on the war in Vietnam: "There were inadequate ports and airfields, no logistic organization, and no supply, transportation, or maintenance troops. None the less, in the face of the grave tactical situation, I decided to accept combat troops as rapidly as they could be made available and to improvise their logistic support." By the end of 1965 US strength in Vietnam stood at 184,000 men.

The first of the additional Signal Corps troops to reach Vietnam was the advance party of Headquarters, 2d Signal Group, commanded by Colonel James J. Moran, which arrived from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in May 1965. Five companies of the 41st

[22]

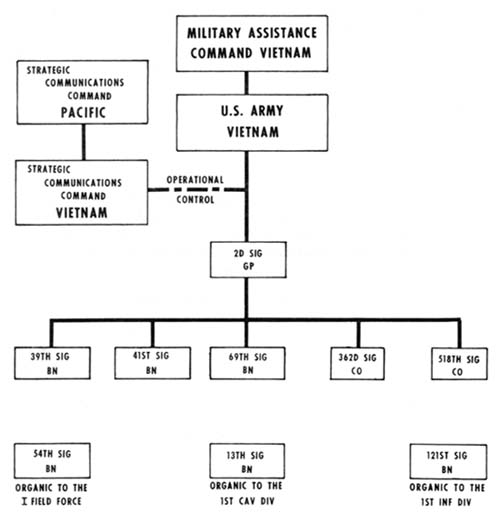

The 2d Signal Group, upon its arrival, assumed command of the 39th Signal Battalion, taking over in fact all the missions previously assigned that battalion, such as the tasks of providing signal maintenance support and operation of the signal supply system in Vietnam. Later, these supply and maintenance missions were turned over to the 1st Logistical Command. Upon acquiring its second signal unit, the 41st Signal Battalion, in mid-1965, the 2d Signal Group made it responsible for all. area communications in the northern half of the Republic of Vietnam in the I and II Corps Tactical Zones, while assigning responsibility to the 39th Signal Battalion for the southern half of Vietnam in the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones. The 362d Signal Company was also placed directly under the 2d Signal Group to operate the tropospheric scatter system throughout the country. The group was assigned to US Army Support Command, Vietnam, and subsequently to US Army, Vietnam, when the latter was established on 20 July 1965, replacing the Support Command. The US Army, Vietnam, was also commanded by General Westmoreland, who served concurrently as Commander, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

These new Regular Army signal units immediately went to work to improve the existing communications and establish communications for new base areas. For example, by mid-July mobile equipment was provided to support the new logistical base being established at Cam Ranh Bay. A 12-voice channel radio relay link was installed to connect Cam Ranh with Nha Trang. A one-position tactical switchboard was put into operation, a mobile communications message center was installed, and high-powered radios linked Cam Ranh into radio nets in Vietnam. In just a few weeks the small switchboard at Cam Ranh had to be replaced with another mobile manual board that was much larger-a 3-position switchboard capable of serving 200 subscribers. Microwave teams with mobile equipment had arrived in Nha Trang to start installation of a 45-channel microwave link between Cam Ranh Bay and Nha Trang. By the end of October 1965 arrangements had been made to ship a fixed-plant, automatic dial telephone exchange to Cam Ranh Bay. The fixed automatic dial telephone equipment

[23]

required a dust-free, humidity-controlled environment for operation, hence special building construction was required.

Colonel Moran's 2d Signal Group was also busily engaged in providing communications support to the combat troops, both to those that were already in Vietnam and to those that were being sent to the country. The group was alerted on 12 August 1965 to provide communications support to the famous 173d Airborne Brigade for an important Vietnam highlands operation in the Pleiku area. The next day the necessary equipment and Signal Corps troops were airlifted to Pleiku, and by evening on 14 August communications got into operation, linking the 173d's operating area into the large fixed backbone system at Pleiku.

Equipment and personnel also had to be redistributed to support arriving units. During the week of 15-21 August, twenty-four tons of signal equipment were moved to the I and II Corps Tactical Zones by special airlift, while an additional twenty-eight tons were awaiting movement. By early September 1965 US Army, Vietnam, had established priorities for providing communications support throughout the country. First priority would go to the

[24]

Command and Control Arrangements

During this period General Westmoreland's joint headquarters was establishing and refining command control arrangements in Vietnam. The final arrangement provided that the Commander, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, exercise tactical control over the US forces through the III Marine Amphibious Force in the northern I Corps Tactical Zone, through the I Field Force in the II Corps Tactical Zone, and through the II Field Force in the III Corps Tactical Zone. Both field force headquarters were modified US Army Corps headquarters. A senior US adviser was responsible for controlling and coordinating US advisory and support troop efforts in the IV Corps Tactical Zone. The Seventh Air Force controlled all US Air Force units, while United States Army, Vietnam, controlled all Army support and logistical units. The I Field Force, initially designated Task Force Alpha, was activated in August 1965, II Field Force headquarters during the spring of 1966.

When Task Force Alpha was activated in August, no signal organization to support it in central Vietnam was available. Interim communications support was provided for Task Force Alpha, headquartered at Nha Trang, by the 2d Signal Group. But on 15 September 1965 the organic 54th Corps Signal Battalion of Task Force Alpha started to arrive and by 1 October began to relieve the 2d Signal Group. The final elements of the 54th closed into Vietnam in October, thus freeing the overtaxed communicators of the 2d Signal Group to work in other areas in Vietnam. Initial communications support for II Field Force at Long Binh, fifteen miles northwest of Saigon, also had to be provided by the 2d Signal Group during the spring of 1966 until the 53d Signal Battalion arrived to provide the needed support.

Additional Communications Control Elements Enter Vietnam

Changes were being made, meanwhile, in higher level communications control, direction, and operations responsibilities. In line with plans for the integrated wideband system that called for establishment of a Defense Communications Agency center in Vietnam, the Deputy Secretary of Defense approved the manning of the Defense Communications Agency, Support Center, Saigon, on 29 April 1965. The support center would provide "system con-

[25]

In September 1965 the Defense Communications Agency, Support Center, Saigon, was redesignated Defense Communications Agency, Southeast Asia Mainland Region. As a part of the Defense Communications Agency organizational structure, the region came under the Pacific area office located in Hawaii. By the end of 1965 the strength of the Southeast Asia Mainland Region had grown from eight men to 100.

In May 1965 Department of the Army directed that those facilities and personnel which would become a part of the Defense Communications System be transferred from US Army, Pacific, to the Army's Strategic Communications Command. This directive was in line with the Strategic Communications Command's mission to operate the Army's portion of the Defense Communications System. In July 1965 the command established an organization to operate the backbone system in Southeast Asia, namely, the US Army Strategic Communications Command, Pacific, Southeast Asia, located in Saigon. Subordinate elements of this new organization were formed in both Vietnam and Thailand and were charged with the actual operation of the system. Elements of the command's 11th Signal Group stationed at Fort Lewis, Washington, arrived in Vietnam in June 1965 to establish the headquarters oŁ the Strategic Communications Command in Southeast Asia. Colonel Henry Schneider was designated as commander of all the Strategic Communications Command's troops in Southeast Asia, while Lieutenant Colonel Jerry J. Enders, who arrived with the unit from Fort Lewis, was designated to command the Vietnam element. Ar-

[26]

Not until 19 August 1965 did the 2d Signal Group turn over to the Strategic Communications Command in Vietnam the responsibility for operation of these systems, along with the transfer of 121 officers and men. These developments increased the command's problems and widened the split in Army communications operations in Vietnam between the Army's Strategic Communications Command's organizations and the area support signal units of the 2d Signal Group under the Army component headquarters, U.S. Army, Vietnam.

A like transfer occurred in Thailand. The US Army's 379th Signal Battalion, which had been organized in Thailand in April 1965, assigned one officer and 71 enlisted men to the Strategic Communications Command element in Thailand in September 1965. The 379th provided mobile communications support to US forces in Thailand similar to that provided by the 39th Signal Battalion in Vietnam.

The Army's Strategic Communications Facility, Vietnam, continued to remain directly under the Hawaii-based Strategic Communications Command, Pacific, headquarters until November 1965, when the station was assigned to the Strategic Communications Command element in Vietnam and was redesignated US Army Strategic Communications Command Facility, Phu Lam. This vital gateway station continued to handle most of the communications passing into and out of Vietnam. The preponderance of the traffic flowed over the high quality circuits of the WET WASH undersea cable to the Philippines.

Earlier at the Phu Lam facility, on 23 March 1965, the first manual data relay center had been activated. At that time the data relay had three connected stations, Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines, Tan Son Nhut Air Base on the outskirts of Saigon, and the Army's 27th Data Processing Unit in Saigon. The station relayed 11,000 cards on its first day of operation. At the end of 1965 the station was processing approximately 400,000 cards per month from seven connected stations.

Early in 1965 the Phu Lam message relay with its twenty-five active circuits also was processing over 250,000 messages per month. By September the station began to experience extreme difficulty in Handling the message traffic. The backlog of service messages became critical when at times up to 1,000 were awaiting ac-

[27]

More Mobile Radio, More Fixed Radio, and Cable

As more troops were deployed throughout the Republic of Vietnam, it became apparent that the existing BACK PORCH system and the planned Integrated Wideband Communications System could not support the critical circuit needs in Vietnam. Contingency transportable tropospheric scatter equipment was provided to Vietnam beginning in March 1965 when six Army mobile terminals arrived. These were used to establish additional circuits north from Saigon to Pleiku through a single relay point situated near the summit of the 7,000-foot mountain, Niu Lang Bian, which stood a few miles to the north of Dalat in the south central highlands. Initially installed as a 24-channel system, its capacity was increased in late summer to forty-eight voice channels when two terminals of another system were redeployed to provide the additional channelizing equipment.

Six larger tropospheric scatter terminals similar to those of the BACK PORCH system were also deployed and operational by the end of 1965. Using their transportable antennas these terminals established twenty-four voice channel links between Pleiku and Da Nang, Vung Tau and Cam Ranh Bay, and between DA Nang and Ubon, Thailand. These systems, along with other tails provided by the 2d Signal Group, had added approximately 35,000 voice channel miles to the Vietnam communications system during the last half of 1965. (Map 3) None of these statistics on facilities, however, included the numerous systems installed by the 2d Signal Group in direct support of combat operations.

Furthermore, the mobile systems were all stopgap measures. Additional circuits of the fixed type were required to support the expanding effort, particularly for the low priority logistical forces and their complex widespread operations. By the end of 1965, the US joint headquarters in Saigon had forwarded three require-

[28]

MOBILE TROPOSPHERIC SCATTER ANTENNA ON NUI LANG BIAN NEAR DALAT was installed and defended by US Army Signalmen in late 1965.

ments packages to the Commander in Chief, Pacific, which, as conceived by the US Military Assistance Command and component communications planners, would provide the necessary long-lines support in Vietnam. The first package forwarded in October was an addition to the programmed wideband system and was later called Integrated Wideband Communications System, Phase 11; it was designed to support up to 200,000 troops. The second requirements package, sent in November 1965, requested a coastal submarine cable system to supplement the integrated wideband system. The third package, forwarded to the Commander in Chief, Pacific, in December 1965, was designed to support up to 400,000 troops.

[29]

MAP 3

This final major addition to the integrated system was later called Integrated Wideband Communications System, Phase III. The system would provide commercial grade service using fixed-plant equipment and construction techniques.

[30]

As the troop buildup continued, from late summer until the end of the year the 2d Signal Group found it more and more difficult to provide enough communications support. By July there were three US Army combat brigades in Vietnam: the 173d Airborne Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Ellis W. Williamson, had arrived in May of 1965; the other two, the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division and the 2d Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division, had arrived in July US and other Free World Military Assistance Forces began to arrive in division-size units along with all required communications support. The first complete US Army division to reach Vietnam was the 1st Cavalry Division, Airmobile, which arrived in September 1965. The US Army's 1st Infantry Division, whose commander was Major General Jonathan O. Seaman, the Republic of Korea Capital Division, and a Korean Marine brigade all arrived in October. By December the lead element, the 3d Brigade, of the US Army's 25th Infantry Division was in Vietnam. Although the planners were allotting a US Army combat area signal company and a signal support company for each division-size force, these units were not initially available. The signal troops already in Vietnam would have to improvise the needed support. Communications service into the system of Vietnam was provided by installing mobile radio relay links connected to the backbone system. Only limited telephone and message service could be made available. The divisions had to install and operate a good portion of their communications, using the organic capability of their division signal battalions, until Army signal support units arrived.

The organic 121st Signal Battalion of the US 1st Infantry Division was one of those that initially had to provide all communication services to its division without the supplemental benefit of Army area type signal support. At first, the 121st was located in a staging area near Bien Hoa, but as the division spread out, so did the signal battalion. The battalion headquarters and two of its three signal companies moved to the division base camp in Di An, approximately fifteen miles northwest of Saigon. Company B, the forward communications company, deployed its three platoons with the far-Hung Big Red One infantry brigades north of DI An.

From this configuration, the organic 121st Signal Battalion operated and maintained all of the communications support for the division. The signalmen installed the myriad command and control as well as administrative telephone and message circuits that

[31]

It was not until May 1966, some seven months after the 121st Signal Battalion became operational in Vietnam, that assistance arrived in the form of the 595th Signal Company. This recently arrived unit of the 2d Signal Group immediately helped relieve the pressure on the 1st Infantry Division's communicators by taking over their switchboard and multichannel radio operations at DI An. The pattern of communications support, as it rapidly evolved in the 1st Infantry Division area, would continue throughout the Vietnam War: the organic signal unit, in this case the 121st Signal Battalion, provided the command and control communications so essential to the field commander and supported the combat operations, while the supporting Army area signal unit provided the administrative or general-user communications, tying the base camps together and affording entry into the countrywide Defense Communications System.

While the 1st Cavalry Division and its organic 13th Signal Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Tom M. Nicholson, were deploying to the An Khe area in the Vietnamese Central Highlands, midway between Pleiku and Qui Nhon, the 586th Signal Support Company arrived in Vietnam. The company was immediately attached to the 41st Signal Battalion and sent to An Khe to support the 1st Cavalry Division. This attachment proved wise because the airmobile division, newest of Army divisions along with its completely equipped but lightweight signal battalion, was about to be tested under fire in the fully developed airmobile concept. The men of the 13th Signal Battalion soon had much more on their minds than installing base camp wire systems and operating switchboards at An Khe, their base of operations.

In October 1965 the North Vietnamese concentrated three regiments of their best troops in the Central Highlands in an area between the Cambodian border and the Special Forces camp at Plei Me. On 19 October the enemy opened his campaign with an attack on the Plei Me camp, which lays twenty-five miles southwest of Pleiku. The North Vietnamese commander attacked with one

[32]

SKYTROOPERS OF 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION PREPARE TO BOARD

ASSAULT HELICOPTERS FOR PLEI ME

regiment, holding the bulk of his division-size force in reserve. With the aid Of concentrated tactical air strikes, the South Vietnamese Army in the area repelled the attack. On 97 October General Westmoreland directed the 1st Cavalry Division into combat, its mission to seek out and destroy the enemy force in western Pleiku Province. Thus began the month-long campaign known as the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley.

Almost immediately, thanks to the helicopter, the division commander, Major General Harry W. O. Kinnard, was able to send a division forward tactical operation center to Pleiku. And hot on its heels followed troops and equipment of the 13th Signal Battalion in heavy-lift cargo helicopters. The battalion rapidly installed a combat radio relay system from the division forward to each of the deployed brigade headquarters-a definite asset throughout the long battle. By means of the system each brigade had direct telephone and message contact with both the division forward tactical operations center and the division base at An Khe. Sole-user command and control circuits were extended from the I Field Force headquarters at Nha Trang to General Kinnard's division forward operations center at Pleiku. The U.S. Air Force liaison officer at the forward command post in Pleiku was also provided with soleuser circuits. These sole-user circuits proved invaluable during the last and most intense phases of the la Drang battle.

[33]

Fortunately the 1st Cavalry Division's 13th Signal Battalion had prepared for this very contingency while still testing the airmobile concept at Fort Benning, Georgia. The problem was solved by placing specially configured combat voice radios in the US Army's Caribou aircraft and orbiting the craft and their radios above those ground units that were using the small portable sets. The result was an airborne relay that could automatically retransmit up to six combat radio nets over far greater distances than the ground range of the radios. Thus at la Drang the units on the ground were served by the 13th Signal Battalion's airborne relay twenty-four hours a day for the last twenty-eight days of the campaign. The optimum altitude turned out to be nine to ten thousand feet above ground, effectively extending the range of the small combat radios fifty to sixty miles, even when the radios were operating in the most dense undergrowth. However, this method of communications, while highly successful in the la Drang area, is very costly in manpower and equipment and raises many radio frequency interference problems.

As the enemy withdrew his assault regiment from Plei Me, it suffered severe casualties from air strikes and the pursuing air cavalry. But when the 1st Cavalry Division put a blocking force behind the withdrawing enemy, only a few miles from the Cambodian border, the North Vietnamese commander committed his remaining two regiments in an attempt to redeem his earlier failure at Plei Me by destroying a major US unit-the 3d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, barely thirty days in Vietnam. The 3d Brigade, however, commanded by Colonel Harold G. Moore, Jr., decisively defeated each enemy regiment in turn and the combined efforts of the division literally swept the la Drang valley clear of North Vietnamese.

As in almost all combat action in the Vietnam War, the la Drang campaign was not an Army effort alone, but rather a combined air and ground effort. Usually tactical fighter aircraft of the Air Force and the Navy were used in direct support of combat operations. Here for the first time in the Vietnam conflict, the US

[34]

The classic campaign of the la Drang valley during the last months of 1965 proved the soundness of the airmobile concept: ground soldiers, aviators, and communicators were successfully molded into a potent, flexible, fighting force.

As US Army and other combat units continued to pour into the country, adding to the communications load of the 2d Signal Group, welcome assistance arrived when the 578th Signal Construction Company landed at Cam Ranh Bay and was attached to the 41st Signal Battalion. Help also came from the 228th Signal Company, attached to the 39th Signal Battalion, which was stationed in the newly established logistical area at Long Binh near Bien Hoa. The 228th provided additional multichannel radio relay capability in the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones. But there were still not enough communications. Brigadier General John Norton, General Westmoreland's deputy commander of the US Army, Vietnam, was emphatic on that score. In the late summer of 1965 he stated in a command report:

Communications continues to be a major command problem. I estimate our capability by 31 December will be 1,735 channels, which, considering customer needs, will make an average deficit of 30%. On some major axes, the deficit will be higher, such as Saigon-Nha Trang (61%), and Nha Trang-Qui Nhon (50%) .

In November 1965 the 1,300-man 69th Signal Battalion (Army) commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Meyer, arrived, along with the 580th Signal Company (Construction). The 69th Signal Battalion took over operation of all local communications support in the Saigon-Long Binh area. Besides providing area signal support for the numerous troop units, the 69th directly supported the headquarters of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, US Army, Vietnam, and the US Army's 1st Logistical Command. To assist in this massive effort, the 593d Signal

[35]

Company, which had been providing communications support in the Saigon area, was attached. The 580th Signal Company, which was capable of installing large fixed cable systems, was also attached.

The last signal unit to arrive during 1965 was the 518th Signal Company, which reached Vietnam in late December. This company, capable of operating mobile tropospheric scatter and microwave equipment, relieved the 362d Signal Company of the responsibility for the operation of the mobile tropospheric scatter and microwave systems in the III and IV Corps Tactical Zones in the South. With these additions Colonel Moran's 2d Signal Group had grown to a strength of nearly 6,000 by the end of the year. (Chart 1)

Even so, adequate communications service could not keep pace with the growing number of "customer" requirements. At the end of 1965 General Norton in his quarterly report continued to list inadequate communications:

The inadequacies of some major axes of long lines communications in USARV still remain alarmingly high: Saigon-Nha Trang 52%, and Nha Trang-Qui Nhon 50%. Programmed installation of multichannel equipment has proceeded as planned, and every measure available to the command is being taken to obviate the situation.

[36]

Impact of Circuit Shortages on Telephone Systems

The lack of voice channels especially affected the telephone system, particularly long-distance service within Vietnam. By July 1965 there were approximately fifty military telephone exchanges in operation and most of these were manual, using a conglomeration of equipment which required operator assistance to reach any party. The 2d Signal Group at that time started to rearrange the limited trunking under a program that required switchboard operators at the numerous switchboards located throughout the country to place all long-distance calls through eight exchanges: at the US Miilitary Assistance Command, Vietnam, headquarters in Saigon, and at Tan Son Nhut, Can Tho, Bien Hoa, Nha Trang, Qui

[37]

The state of general-user telephone service in Vietnam during the mid-1960s is best described in a report prepared by the joint Logistic Review Board. It states in part:

Operators were too busy to monitor effectively their circuits. Pick-up times of 3 to 5 minutes were common on the busy boards during peak traffic hours. Thus, not only were subscribers forced to route their own calls, but after completion of the call through the first operator, if the distant operator failed to answer, the calling party could not flash the operator back but was disconnected to join the queue again, . . . This led to the situation where, while one staff officer was tying up the operator by demanding an explanation of slow service, several other staff officers were cranking their generator handles furiously trying to get the attention of the same operator so that they, too, could discuss his reasons for being asleep at his job.

Automatic Telephone and Secure Voice Switch Plans

As early as mid-1964 the US Military Assistance Command headquarters and service component staffs had recognized the need for an integrated telephone network in Vietnam, including the need for direct distance dialing through automatic long-distance switches to be located at DA Nang, Pleiku, Nha Trang, and Tan Son Nhut. The rapid buildup overtook these early efforts. In September 1965, General Westmoreland's joint headquarters in Saigon restated a requirement for a general-user automatic telephone system for South Vietnam. As a result, following a conference in Hawaii at the headquarters of the Commander in Chief, Pacific, the Pacific area headquarters of the Defense Communications Agency was asked to develop a plan for automatic telephone service for Southeast Asia. The conferees had established a need for fifty-four fixed automatic dial telephone exchanges. Of these the

[38]

Earlier, in May of 1965, the Army Signal Corps planners in Vietnam and at US Army, Pacific, headquarters in Hawaii had realized that automatic dial telephone exchanges were needed immediately in South Vietnam. A proposal was promptly made to the Department of the Army in Washington that, as an interim measure, fifteen 400-line transportable dial telephone exchanges be provided. As stated in the 1965 History of US Army Operations in Southeast Asia:

[the staff at Headquarters, US Army, Pacific] realizing that procurement of fixed plant equipment and the construction necessary to house such equipment would be unable to keep pace with the expanding communication requirement, developed criteria for a model transportable dial central office, and recommended that . . . [Department of the Army] expedite design, procurement, and fabrication of the transportable offices for early shipment to ... [Southeast Asia].

As a result of these actions Department of the Army in late 1965 ordered shipment of two fixed dial telephone exchanges, one of 2,400 lines for Cam Ranh Bay and another of 1,200 lines for Qui Nhon, and approved procurement of twelve more fixed dial exchanges and six 600-line transportable exchanges. In addition six large Army manual switchboards, modified for use as manual longdistance switchboards, were scheduled to arrive by January 1966, and would provide long-distance service until the automatic tandem switches became available.

Besides these large requirements for general-user service, there was also an urgent need for certain subscribers to be able to discuss classified matters over the telephone system. Installation of a secure voice switchboard was begun in Saigon on 22 September 1965 and the board became operational on 18 October when the first subscribers were tied in. By December 1965 this system, which consisted of seventeen subscribers in Vietnam, was completed. Voice-scrambling to frustrate enemy interceptions had hitherto been limited to a few fixed installations because of the complex and costly equipment. But there was a pressing need for its appli-

[39]

Fragmented Communications Control Is United

During the fall of 1965, as the overtaxed US Army Signalmen toiled to provide the best communications support possible with their limited resources, it became more and more apparent that the command and control arrangements over US Army Signal troops and systems in Vietnam were not responsive to operational requirements because they were not unified or single. These arrangements, as previously discussed, charged two separate US Army Strategic Communications elements in Vietnam, both under command of their headquarters in Hawaii and both subject to Defense Communications Agency direction, with responsibility for long-lines circuits in Vietnam. Neither of these elements was operationally under General Westmoreland. Moreover, the 2d Signal Group, which was responsive to the US Military Assistance Command and which came under the command and control of Commanding General, United States Army, Vietnam, had responsibility for the tails of the long-lines system over which numerous Defense Department circuits were extended to the customers. In short, the circuits and systems were intertwined but their command and control were divided.

Major General Walter E. Lotz, Jr., who served as General Westmoreland's communications-electronics staff officer from September 1965 to August 1966, described this fragmentation. He said:

A number of sites were occupied jointly by . . . [US Army Strategic Communications Command and 2d Signal Group] units. When failures occurred in circuits transiting the systems of both, each unit pointed its finger at the other. . . . When a facility failed, determination of what circuits had been affected was primarily determined by the complaints of the operators at the circuit ends, rather than from circuit records, . . . , . . . when circuits also traversed cable systems installed by base commanders, problems were further compounded. As a result of these frustrations, I wrote a message which General Westmoreland dispatched to the Army Chief of Staff, recommending common command and control of the . . . [US Army Strategic Communications Command and United States Army, Pacific] theater Signal elements in South Vietnam.

[40]

Consider it urgent to resolve fragmentation of command and control of Army Signal Units in . . . {Republic of Vietnam] to ensure communications system is responsive to operational requirements, has unity of management and control and efficiently utilizes marginally adequate resources. . . . I believe extraordinary measures required. Signal Officer, . . . [US Army Vietnam] should exercise operational control over all . . . [US Army Vietnam and Strategic Communications Command] elements in . . . [the Republic of Vietnam].

A Department of the Army team, headed by Major General John C. F. Tillson III, which included representatives from Headquarters, US Army, Pacific, at once hurried to Vietnam in November to examine the situation and discuss the matter with General Westmoreland. As a result, on 1 December 1965 the Department of the Army placed the Strategic Communications Command's elements in Vietnam under the operational control of the Commanding General, US Army, Vietnam. The Department of the Army further directed the Commander in Chief, US Army, Pacific, General John K. Waters, and Commanding General, US Army Strategic Communications Command, Major General Richard J. Meyer, to provide a plan whereby all Army Signal elements down to field force level would be placed under a US Army Signal Command, Vietnam.

From the time the 39th Signal Battalion arrived in Vietnam in 1962 through the turbulent year of 1965, the US Army Signal Corps troops were continually responding to changing situations and requirements. Even from the early days in 1962 much of the communications support had to be improvised. Although plans, concepts, and programs were taking shape during the first big buildup year of 1965, actual resources in the theater remained limited and the communicators were hard pressed to provide adequate service to the customers. There was no established commercial system in Vietnam to fall back on, as there had been in Europe in World War II. In October 1944, only four months after the Allied troops invaded Europe, the rehabilitated civil system yielded about 3,000 circuits, totaling over 200,000 circuit miles, supplemented by about 100,000 circuit miles of new construction built by the signal forces of the US Army.

[41]

[42]

The communications system, despite the handicap of having to provide more service than in any previous war and of operating under severe geographical and tactical equipment limitations, has responded brilliantly to the burgeoning requirements of a greatly expanding fighting force. No combat operation has been limited by lack of communications. The ingenuity, dedication, and professionalism of the communications personnel are deserving of the highest praise.

[43]

Go To: