COMMUNICATIONS MATURE AND

MOVE TOWARD VIETNAMIZATION,

1968-1970

CHAPTER IX

U.S. Army Signal Troops and Tet: 1968

During 1967 Hanoi evidently concluded that the chances for success in its campaign to control South Vietnam were diminishing. The South Vietnamese Government was becoming stabilized as a result of a new constitution and the nationwide free elections held during September and October 1967. The nation's economy and its armed forces were showing improvement. As a result of continual military pressure applied by the Free World Military Assistance Forces during 1966 and 1967, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces had been compelled to withdraw from the areas close to the population centers of South Vietnam and move into their more remote base areas or their secure sanctuaries in Cambodia and Laos. Hanoi decided a major change of strategy was necessary. A large offensive would be launched in the Republic of Vietnam. At the same time the civilian population would be incited to rise up against the government and the soldiers of the Vietnam Army would be encouraged to desert. Exactly what Hanoi expected of this strategy is still uncertain. The probable intentions of the enemy were described by General Westmoreland in his report on the war in Vietnam:

He probably had many things in mind-not the least of which was the necessity to do something dramatic to reverse his fortunes. He surely hoped that his dramatic change in strategy would have an impact on the United States similar to that which the battle of Dien Bien Phu had on the government and people of France. In this way he might hope to bring about a halt of the U.S. effort and the withdrawal of the U.S. Forces.

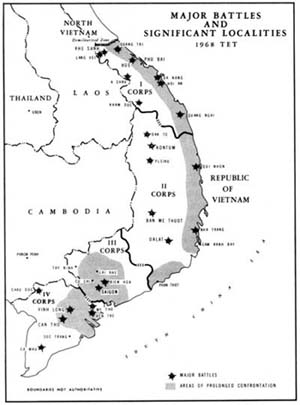

During late December 1967 and January 1968, Hanoi infiltrated troops and supplies into forward positions and into the population centers of South Vietnam. The offensive was launched 29-30 January in the I and II Corps Tactical Zones, and 30-31 January in the remainder of the country under cover of a seven-

[103]

During May and early June the enemy launched new attacks, primarily against the Saigon area and in the northern part of South Vietnam. Before these assaults, and after them too, a series of rocket attacks were made against military installations and in some cases rockets were launched indiscriminately against the civilian population.

By the end of June 1968 when General Abrams took command of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, upon General Westmoreland's departure for his new duty as the Army Chief of Staff, enemy losses were estimated at 120,000 during the first six months of 1968. The South Vietnamese had come through this major enemy offensive with more confidence, stronger armed forces, a strengthened government, and, last, a population that had disregarded the call for a general uprising.

Building Communications in the Northern Provinces

Before Tet General Westmoreland had initiated countermeasures while the enemy was moving into forward areas. As large numbers infiltrated into the Republic of Vietnam population centers during December 1967 and January 1968, intelligence information began to be received at General Westmoreland's joint headquarters that a major offensive was to take place. Consequently, in mid-January, General Westmoreland strengthened the U.S. forces in the Saigon area and moved the 1st Cavalry Division and elements of the 101st Airborne Division into the northernmost provinces of South Vietnam. Because of the heavy reinforcement in the northern I Corps Tactical Zone in anticipation of a major enemy offensive, General Westmoreland decided to open in late January a temporary control headquarters in that area. This forward headquarters of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, under the command of Lieutenant General William B. Rosson, was designated in March as Provisional Corps, Vietnam, and was ultimately redesignated the U.S. Army XXIV Corps. The corps

[104]

MAP 5

was placed under the operational control of the III Marine Amphibious Force, which had responsibility for operations in the entire I Corps Tactical Zone.

[105]

Communications facilities for General Westmoreland's forward command post, including the existing Phu Bai dial telephone exchange, were bunkered in, or revetted, and cables were placed underground. Work continued at a fast pace despite an around-theclock enemy rocket attack on Phu Bai during the first three days of February. Though numerous rounds landed near the sites and the revetments were hit by many shell fragments, the equipment remained undamaged.

In the midst of the battle that raged in Hue, the 459th Signal Battalion was ordered to provide secure teletypewriter message service to the fire support coordinator located with the Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division command post at an old fortress, the Citadel, in Hue. The only means of reaching the Citadel was by U.S. Navy landing craft, which had to traverse the Perfume River in order to reach the canal that circles the fortress. A four-man team led by 1st Lieutenant John E. Hamon was organized to move and operate the equipment. During the trip to the Citadel the landing craft came under heavy mortar attack and two of the enlisted men and the lieutenant were wounded. Lieutenant Hamon, despite his wound, and the one uninjured enlisted man put the equipment in operation and provided the critical communications support for over twenty-four hours until help arrived.

The 459th continued to provide support to the joint forward headquarters in

Phu Bai until the newly arrived 63d Signal Battalion headquarters, commanded

by Lieutenant Colonel Elmer H. Graham, took over the mission of the provisional

organization in March of 1968.

Additional Free World Military Assistance Forces were de-

[106]

These "draw-downs" by bits and pieces to provide the resources required in the north had placed a heavy burden on the brigade. As General Van Harlingen explained in his debriefing report: "The 1st Signal Brigade was thrown into the midst of an administrative maelstrom, with personnel and equipment attachments and all the accompanying paper storm."

The story of the 459th Signal Battalion, as it was provisionally organized and deployed, is unique since the deployment occurred as the Tet offensive took place. The hastily organized battalion had to respond quickly and install and operate the vital communications needed, even though it was under fire. Being under fire, however, was not new to the men of the 459th; many of them had come from other locations in Vietnam that were also under attack. At this time all the signal troops of the divisions, field forces, and 1st Signal Brigade deployed throughout South Vietnam were simultaneously installing communications in support of the combat forces and defending their positions. They were handling increased communications traffic loads that resulted from the fighting and were repairing and restoring disrupted communications services. It was commonplace that in many places signalmen had to fight and at the same time provide communications support. One element of the 1st Signal Brigade, the communications control center with its communications status-reporting system used to control and manage communications passing through more than 220 locations in Vietnam, found itself in a unique position. The reporting system was capable and did provide battle information in considerable detail concerning enemy activity to the Military Assistance Command and U.S. Army, Vietnam, operations centers.

[107]

Troops were ordered to be prepared to install and restore command and control communications while under attack in all cases. I consider it essential that the Signal troop be trained and prepared to work under fire, even when he must deliberately expose himself to do so. . . . Because of the overall quality of the American soldier in Vietnam, and, due in part to stimulation of the enemy's offensive, at no time did the Signal troop fail to come through when required. Equipment was cannibalized, antennas restored, cable repaired, isolated sites defended and new links activated both night and day during periods of intense enemy rocket, mortar and small arms fire.

Thousands of dramatic incidents, both recorded and unrecorded, occurred as the signalmen fought, in one way or another, to keep the communications "in." A few are told here as they happened during Tet 1968.

On 1 February, during the height of the heavy fighting in Hue, close to the Demilitarized Zone in the north, the Senior U.S. Military Officer in the besieged city considered withdrawing the signal troops of the 1st Signal Brigade's 37th Signal Battalion from the Hue tropospheric scatter site to avoid their being overrun. But General Van Harlingen knew the site was critical because it provided the main communications with the beleaguered U.S. Forces at Khe Sanh. He directed Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Davis, Jr., the 37th Battalion commander, to order the men to remain at the site so that the vital link with Khe Sanh could be kept operational, and at the same time he requested immediate assistance from the U.S. Marine forces fighting near the Hue signal site. For the next thirty-six hours the small installation was surrounded. The signalmen beat off repeated assaults by an estimated Viet Cong battalion attacking with small arms, automatic weapons, and rockets. Helicopters trying to reach the surrounded signalmen were turned back by machine gun fire; it was impossible to evacuate the wounded. One soldier with a shattered arm was desperately in need of medical help. His fellow signalmen treated the wound while they received instructions by telephone from Phu Bai. Two companies of Marines, trying to reach the site from the U.S. Advisor's compound three blocks away, finally gained the signal site after thirty-six hours of fighting.

While heavy fighting was going on at the Hue tropospheric scatter site, U.S. troops near the Laotian border at Khe Sanh were under constant mortar and rocket attack. A direct hit on a bunker by a rocket killed a lieutenant and an enlisted man of the team operating the Khe Sanh mobile tropospheric scatter terminal. Three

[108]

At Dalat, in the mountains of south central Vietnam, signalmen of the 362d Signal Company and Company E, 43d Signal Battalion, both attached to the 1st Signal Brigade's 73d Signal Battalion, were in continuous action from 1 through 6 February 1968. During the afternoon of 1 February members of the 218th Military Police Detachment were pinned down in their small compound by fire from an estimated two platoons of Viet Cong. Major William R. Crawford, the commander of 362d Signal Company, upon learning of the plight of the military policemen, immediately organized and led a 20-man rescue team. The small force of signalmen engaged the enemy with individual weapon and grenade fire, evacuated wounded military policemen, and laid down a base of fire that enabled the uninjured soldiers to withdraw. At the same time, inside Dalat, Captain Donald J. Choy, the operations officer of the 362d, led a heavily armed convoy to the Villa Alliance Missionary Association compound, which was surrounded by Viet Cong. The signalmen fought their way to the compound and successfully evacuated the thirty-four occupants. All told, the signal troops of the 362d Signal Company and Company E, 43d Signal Battalion, rescued and provided shelter for more than sixty noncombatants.

Incredibly, there were no serious communications failures during the first weeks of the offensive. The fixed communications site at Hue, which was operating on commercial power, went off the air late in the evening of 31 January 1968 when the power station was overrun and the backup power generators located at the site had become inoperative. Communications at the site were restored by the afternoon of 2 February after replacement generators had arrived with a convoy that had gotten through, despite two ambushes on the way.

During a mortar attack on the Phu Lam signal site close to Saigon on 8 February, a vital 50-ton air conditioner serving the large tape message relay was knocked out. For several hours the station could process only "Flash" and "Immediate" precedence traffic. After intense efforts the air conditioner was repaired and became operational the following day.

A considerable number of communications failures did occur when multipair communications cables that had been installed

[109]

CABLE TEAM AT WORK DURING TET OFFENSIVE

[110]

By 5 February most of the cables had been restored, but in the areas where heavy fighting continued, such as Saigon, numerous cables were still out. Essential communications traffic continued to flow, nonetheless, rerouted through extemporized circuits.

During the period of the heaviest attacks, 31 January through 18 February 1968, only three mobile multichannel systems operated by the 1st Signal Brigade went out because of combat damage, and then only for a brief time. Whereas the cables that had been constructed above ground were damaged considerably, those which had been buried suffered little. General Van Harlingen, commenting on the effects on communications during the first weeks of the Tet offensive, declared: "Miraculously, although Signal troops sustained several hundred casualties, there were no disastrous interruptions of communication at any time during the first few weeks of the offensive."

Later, however, the enemy was able to disrupt communications and inflict heavy casualties at a signal site in southern Vietnam. During the night of 13-14 May 1968 the 25th Infantry Division signal site atop Nui Ba Den, a lone mountain about forty miles west of Saigon near Tay Ninh, came under a mortar, rocket, and coordinated ground attack. Some fifteen signalmen of the 1st Signal Brigade were also at the site, operating corps area radio relay systems. The enemy penetrated the perimeter and severely damaged the equipment and facilities. Twenty-three U.S. soldiers were killed, three were wounded, and one was missing as a result of the enemy assault. Shortly before I arrived in Vietnam in September 1968 to serve as General Van Harlingen's deputy brigade commander, the Nui BA Den site was again attacked, early in the morning of 18 August. Even though there were some casualties, damage was light, and the enemy was successfully repulsed.

[111]

Throughout the enemy's 1968 Tet and summer offensives the area support battalions of the 1st Signal Brigade continued to supplement the organic communications of the field forces, divisions, and separate brigades. But even before the Tet offensive, it had become evident to General Van Harlingen that excessive duplication existed between the long-lines area system supporting the U.S. and Free World Military Assistance Forces and the numerous networks which had previously been installed to support the U.S. advisers. Economy and efficiency dictated their consolidation into single systems, one within each of the four corps tactical zones. This consolidation would not only promote economy in the use of equipment and manpower resources but would also increase the capabilities of the field force commander by providing communication links between U.S. And South Vietnamese units. It would provide each field force commander with a single network for control over his own troops and for execution of his mission as the Senior Advisor within his corps tactical zone.

General Westmoreland approved the concept in November 1967 and the consolidation was begun at once. Because the III Corps Tactical Zone appeared to be the one most cluttered with duplicated links, General Van Harlingen began consolidation in that area. Within the first month, his efforts netted a savings of twelve radio relay links with all their associated equipment and operating personnel. These assets immediately proved valuable in providing badly needed communications to support the 25th Infantry Division in War Zone C, northwest of Saigon, during Operation YELLOWSTONE in early 1968.

The consolidation, which streamlined the communications systems in the corps tactical zones saving a considerable number of men and much equipment, was finished in December 1968. The single system concept for support of operations in each of the corps tactical zones became the doctrine for area signal support in Vietnam. One of the more significant features of this doctrine was that the combat commanders could, in an emergency, obtain immediate communications support from the local representatives of the supporting area battalions of the 1st Signal Brigade without validation from Headquarters, U.S. Army, Vietnam. On many occasions the resulting close relationship between the brigade's area battalion commander and the division or field force for which he was providing signal support meant the difference between "go" or "no go" on short-notice combat operations.

[112]

The consolidation of communications systems resulted also in more efficient disposition of personnel and equipment. Consequently, 1968 was another year of major reorganization for the 1st Signal Brigade. With the buildup of forces, communications facilities underwent further expansion, upgrading, and reorientation. During 1968 signal companies and battalions continued to deploy to Vietnam, joining the 1st Signal Brigade, while most of the signal organizations already in Vietnam were busy submitting modified tables of organization and equipment. All this reorganizational activity was a clerical nightmare, but it was unavoidable because the signal units were operating with minimal resources and, as their mission expanded, more resources had to be provided.

One of the more significant organizational changes made by the 1st Signal Brigade during this time was the activation of still another signal group, which was to operate in the I Corps Tactical Zone. As of mid-1968, the U.S. Army's XXIV Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Richard G. Stilwell and based in Phu Bai, with responsibility for the I Corps Tactical Zone, had operational control of three U.S. divisions: the Army's 1st Cavalry and 101st Airborne Divisions and the U.S. 3d Marine Division. This corps also had close liaison responsibilities with the Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division, headquartered in the old imperial city of Hue. In July 1968 the 1st Brigade of the 5th Mechanized Infantry Division arrived in Vietnam and was also assigned to the XXIV Corps tactical area. It was soon obvious that the 1st Signal Brigade's 63d Signal Battalion was overburdened by having to provide communications support to all U.S. Forces in the two northern provinces of Vietnam as well as the organic communications for the XXIV Corps.

By September 1968 it was plain that an additional signal group headquarters would be required to provide command and control of the signal elements in the I Corps Tactical Zone. The span of control within the 21st Signal Group had become too great; the group had six battalions assigned and was deployed over two-thirds of South Vietnam with a strength of about 7,000 men. Consequently, a new signal group headquarters, known as the I Corps Tactical Zone Provisional Signal Group, was formed on 8 September 1968. The staff for this new signal group was formed, as in other cases, by tightening the belt and drawing from other 1st Signal Brigade units. The I Corps Tactical Zone Provisional Signal Group, commanded by Colonel Mitchel Goldenthal, became oper-

[113]

ational in December 1968, with its headquarters in Phu Bai. The group had responsibility for all area communications support in the I Corps Tactical Zone and assumed command of the 37th and 63d Signal Battalions. On 1 July 1969 this group was redesignated the 12th Signal Group, commanded by Colonel Albert B. Crawford. By then the 1st Signal Brigade, with its extensive communications responsibilities throughout Southeast Asia, comprised six signal groups and twenty-three battalions. (Chart 2)

In December 1968 there were scattered throughout the Republic of Vietnam approximately 220 installations for which the Corps Area System provided communications. To meet the requirements

[114]

MAP 6

of these large corps area communications facilities, ten signal battalions of the 1st Signal Brigade were deployed throughout the country. (Map 6) These battalions operated approximately 250 area communications links, carrying over four thousand voice

[115]

[116]

Go To: