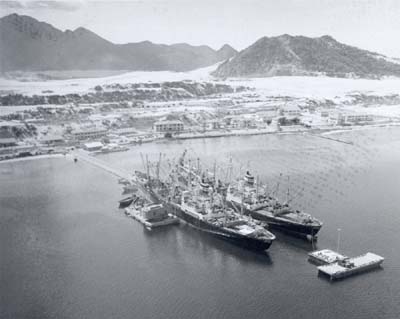

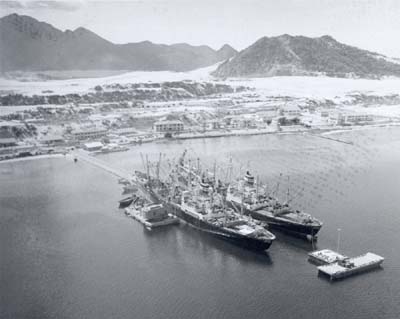

PORT AT CAM RANH BAY, AUGUST 1965

CHAPTER III

Initial Engagement of Engineers

Just seventeen days after they were alerted, on 27 April 1965, the 35th Group headquarters and the 864th Battalion dispatched an advance party to the Republic of Vietnam. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas C. Haskins, executive officer of the 35th Group, members of the party arrived in Saigon on 3 May and coordinated with the newly activated 1st Logistical Command of the Army in planning for the arrival of the 35th Group. They learned that the group was to operate under the command of Colonel Robert W. Duke (not to be confused with the Engineer officer of the same last name), head of the 1st Logistical Command, whose headquarters was located in the outskirts of Saigon close to the international airport at Tan Son Nhut.

Tactical plans being formulated at the time contemplated putting the American marines in the northernmost political-military section of the country, known as I Corps Tactical Zone. Since it already possessed an operating port at Da Nang, the U.S. Navy, normally charged with logistical support of its marines, was given the responsibility for support activities throughout that zone. In the other three zones the Army was to arrange for reception of troops, equipment, and supplies – a task assigned to the 1st Logistical Command. After reviewing anchorages, ports, roadnets, and security considerations, the command decided to expand port and airfield capacities at Saigon, Qui Nhon, and Vung Tau. In addition a massive construction project was to transform the Cam Ranh peninsula with its well-protected natural harbor into a major port and logistical complex. The matter of how best to apply the slim resources of the incoming 35th Group was studied by its advance party and Army command elements in Saigon. Jointly they arrived at the priorities of troop construction and developed a plan for the initial distribution of the 2,300 engineer troops that were to arrive at the end of May. They selected landing points for the group and made the necessary arrangements for the landings.

Preparations To Receive First Units

A provisional post detachment in the person of a single lieu-

[36]

tenant had arrived at Cam Ranh Bay on 22 April and was working with the government of the Republic of Vietnam and the Vietnamese Navy to plan for the arrival of the first US troop contingent. The lieutenant and the advance parties concluded arrangements for security for the landing, acquisition of land, and organization of an indigenous labor force to support engineer operations.

Before the US troop buildup, land used by US advisory troops was either leased from private owners or provided by the government of Vietnam. When there were squatters the United States paid the cost of indemnification and relocation but the title itself was obtained and held by the government of Vietnam, which lacked the financial resources to pay the real estate costs for the influx of US troops. Such a system for land acquisition was obviously unrealistic. For example, in the spring of 1965 when the marines arrived at DA Nang two Army officers from the Military Assistance Command had to negotiate on the spot with 1,800 different land owners and spend $620,000 to get the land at DA Nang.

Although the government of Vietnam established a real estate board during the spring of 1966 to deal with US real estate officers, acquiring land continued to be an annoying problem for the US engineers. The seriousness of the difficulties as early as 1965 is reflected in an unofficial change in troop structure in the late summer of that year. When a terrain analysis detachment of five officers and five enlisted men arrived in Saigon ready to perform its customary mission of evaluating land forms, topography, and surface characteristics, it was placed within the Engineer Section of the US Military Assistance Command where it became the real estate office within that section. The terrain analysts promptly became embroiled in real estate matters, never performing the mission for which they had been dispatched.

Because of the absence of a local labor pool in the Cam Ranh Bay area, General Westmoreland in April 1965 recommended to the government of Vietnam that it resettle refugees and displaced persons there. The recommendation was well received and the government began planning for the relocation of approximately 5,000 Vietnamese in a model village to be built at Ba Ngoi across Cam Ranh Bay from the peninsula. Settlers began to arrive at the village as early as July 1965 and soon provided much needed support for various engineer activities in the area. By mid-1968, the population of the village had climbed to over 15,000.

The priorities for troop construction and the plan for the initial distribution of construction troops were dictated by the importance attached to ports and harbors that could accommodate

[37]

oceangoing vessels. The fact that the US logistical system in Vietnam was in its infancy and that there was no delineation of front lines or rear areas led to the establishment of three major combat support areas for the Army. These were Saigon with its neighboring Vung Tau, Cam Ranh Bay, and Qui Nhon. At first construction would be concentrated in these areas. Contractor construction was at this time heavily committed in the Saigon area but was to be extended to develop a fighter base for the Air Force on the Cam Ranh peninsula as soon as possible. The first Army engineers were to work at Cam Ranh and Qui Nhon. With the arrival in June of the 35th Engineer Group the urgent projects of developing Qui Nhon and Cam Ranh Bay into port-depot staging area complexes got under way.

The main body of the 35th Engineer Group headquarters and headquarters company left Fort Polk, Louisiana, on 12 May 1965, and along with the 84th Battalion, the 864th Battalion, the 513th Engineer Company (Dump Truck), the 584th Engineer Company (Light Equipment), the 178th Engineer Company (Maintenance), and the 53d Engineer Company (Supply Point), boarded the USNS Eltinge and left San Francisco, California, for the Republic of Vietnam on 13 May. The time of arrival was set as 30 May; however, the ship, a World War II Liberty ship just out of mothballs, had mechanical breakdowns almost daily. Finally, multiple pump failures occurred in mid-Pacific and the ship had to be towed 500 miles to Midway Island where all the troops and the cargo were transferred to the USNS Barrett. After some additional delay occasioned by the loading operation, the Barrett sailed for Vietnam via the Philippines.

Although the journey was not an auspicious beginning for the engineer story in Vietnam, it had its bright side for the troops. The delay at Midway provided the men an opportunity for recreation and exercise after the cramped living conditions aboard the Eltinge. The Barrett continued to its original destination, the Philippines, where it discharged dependents and other travelers before setting out for Vietnam. This unprogrammed stop for the engineers permitted the leader of the advance party, Colonel Haskins, to fly in from Saigon and brief commanders and staff officers. When plans were finished, Colonel Haskins flew back to Saigon to complete preparations for landing and deploying troops when they reached Vietnam.

[38]

PORT AT CAM RANH BAY, AUGUST 1965

The First Engineers at Cam Ranh Bay

On 9 June 1965, just twenty-seven days after the main body had left for Southeast Asia, the USNS Barrett dropped anchor in Cam Ranh Bay and the first major contingent of US Army engineers landed. These engineers found a peninsula seventeen miles long and five miles wide at its widest point, connecting with the mainland at the northern extremity and forming a protected harbor of approximately forty square kilometers with depths to twentyfour meters, and covered with low shrubs in the north. Near the tip of the peninsula was a group of granitic mountains averaging one hundred meters above sea level and a small freshwater lake. One worn, unpaved road existed on the peninsula, and one narrow pier, recently built by contract for the US Operations Mission in Vietnam, thrust out into the bay. This finger pier could accommodate no more than two ships at any one time. A small 800-foot airstrip which the French Army had built and which had been used by the pier contractor paralleled the shoreline. The peninsula was bleak and barren, but from this scattering of sand and shrubs

[39]

soldiers were to build one of the major logistical bases and supply depots in the Republic of Vietnam.

The party that disembarked on the peninsula consisted of the 35th Group headquarters, the 864th Engineer Battalion, Company

[40]

D of the 84th Engineer Battalion, the 584th Engineer Company, the 513th Engineer Company, the 178th Engineer Company, the 53d Engineer Company, and the 22d Finance Detachment. The remainder of the 84th Battalion proceeded north aboard ship to Qui Nhon, arriving there two days later. Several of the units that disembarked at Cam Ranh Bay left shortly thereafter for other locations in South Vietnam. Company D of the 84th left Cam Ranh on an LST (landing ship, tank) for Vung Tau on orders from the 1st Logistical Command. The 22d Detachment was transferred to Nha Trang, the maintenance company to Saigon. The supply point company remained at Cam Ranh but later passed from the control of the 35th Group to that of the Cam Ranh Bay Logistics Area. Remaining on the peninsula at Cam Ranh Bay and under the command of the 35th Group headquarters were the group headquarters company and the 864th Battalion, as well as the dump truck and light equipment companies.

Most of the engineers at Cam Ranh Bay in 1965 were professional soldiers. (Map 3) At this early stage in the war the Army was not yet an army of conscripts, and many of the senior officers and noncommissioned officers had been in service long enough to see action in Korea and even in World War II. There were few at Cam Ranh who had not welcomed their new assignment, and these first engineers were particularly competent, aggressive soldiers. From the time of his landing at Cam Ranh Bay, the commanding officer of the 35th Engineer Group, charged with troop construction operations, also had the mission assigned by the Commanding Officer, 1st Logistical Command, of establishing the Cam Ranh Bay Logistics Area and commanding all 1st Logistical Command troops in the area. Thus Colonel Hart and his staff found themselves in a dual role in which they had to plan, establish, and operate area mail, chaplain, and medical services; operate a military police detachment; procure rations and establish and operate depots for all supplies; and concern themselves with all manner of nonengineer functions. This arrangement lasted for the better part of three months until the command of the Cam Ranh Bay Logistics Area passed to an incoming quartermaster unit.

The Engineers Tackle the Environment

The first night the engineers stayed on Cam Ranh peninsula, Colonel Hart had machine gun positions established and listening posts set up. The rain poured down, indifferent to the calendar's dictate for the dry season. The Viet Cong made their presence felt with some long-range, ineffective sniping. The uninitiated spent a

[41]

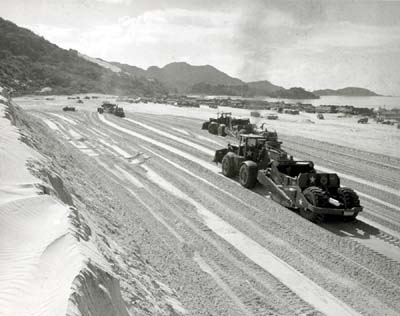

EARTHMOVERS LEVEL SAND at Cam Ranh Engineer Complex, 1965.

very apprehensive first night, but the presence of seasoned officers and noncommissioned officers strengthened morale.

For the next few days Vietnamese troops provided security while the engineers set up bivouac. A campsite immediately adjacent to the landing point quickly appeared as the engineers set up their cots and arranged their belongings in an inescapable sea of unstable sand. Tents for headquarters as well as for kitchens and for vehicle maintenance added more dark green canvas in neatly aligned rows above the orange-yellow sand that glittered in the tropic sun.

After the base camp had been established, the engineers assumed their full responsibility for security. A mutual security plan was worked out and coordinated locally with the commander of the Vietnamese naval training establishment, Lieutenant Commander Ha, but security measures were a heavy burden until 12 July when a battalion of the 2d Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, arrived at Cam Ranh. In October the responsibility for providing security for the Cam Ranh peninsula and the surrounding area was

[42]

given to the 2d Marine (Dragon) Brigade from the Republic of Korea. The major threat remained long-range sniping, but the danger of direct assault was always present.

Along with security, the chief problems of the engineers were the sand and the lack of natural construction materials on the peninsula. The first requirement was to get the equipment to the various work sites, a task that proved to be extremely difficult because the sand was wind-deposited, of uniform gradation, consisting of spherical rather than irregular particles and extremely hard to stabilize. In some places it was fifteen to twenty feet deep over rock formations. The first trails cut through this sand by bulldozers were frustratingly unstable. Heavy vehicles were immobilized in the sand and dozers had to stay along the trails to tow them from the shore to the work areas. As a first step it was necessary to stop everyone from driving until the drivers could be taught how to operate properly in sand. Tire pressure was reduced below the minimum prescribed in technical manuals and sand dunes were climbed by contour driving rather than by direct approach. As General Frank S. Besson, Jr., remarked on a visit to Cam Ranh early in 1966, "we probably ruined a lot of tires but saved a lot of transmissions."

Sand was everywhere and persisted in invading even those places constructed specifically to keep it out. The onshore winds carried sand into kitchens, foodstuffs, and clothing. The gleaming granules multiplied the already intense heat, making even the shade offered by the dark green tentage hot and uncomfortable. When tent sides were raised to vent the hot, confined air, the sand moved uninhibited through the modest engineer homes. Escape from the elements was hard to find on Cam Ranh, and the engineers often welcomed the blowing sand as a relief from the searing sunlight reflected off the blue waters of the ocean and the seemingly limitless dunes.

The sand caused serious maintenance problems. The pusher fan on some tractors drew flying sand into the engine, pushing it through the radiator at tremendous speeds. The engineers resorted to field expedients to keep the equipment in use. Covers of canvas or sheet metal kept some of the sand out of the engines; damaged, worn, and abraded parts were replaced by parts fabricated locally. The sand posed a tough problem to repairmen, operators, and builders.

A major priority was assigned early to the construction of a firm road network on the peninsula, but success here depended on stabilizing the sand and discovering enough suitable natural resources. The engineers conducted an extensive reconnaissance to

[43]

uncover construction materials of any sort, but the most sought-for material in the early operations was rock. As one commander explained, "Rock was the word over there. I woke up in my sleep saying, 'Rock, rock, rock.' " Just outside their perimeter the engineers found an abandoned rock quarry that Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen had opened when they were building the US Operations Mission pier. Company A of the 864th reopened the quarry and soon began producing crushed granite for road construction.

Laterite, a soil unique to tropical regions, occurred extensively in Vietnam both as a hard massive crust and in the alluvial or river-deposited silt. Both types, red to brown in color, were rich in the secondary oxides of iron and aluminum. Engineer units came to use laterite extensively as a subgrade material for constructing roads and airfields. Unfortunately, Cam Ranh peninsula had no laterite. Later the laterite was hauled from the mainland for subgrades, but throughout the early months other means of stabilization had to be found.

Lumber was another critical material. Although intelligence had reported that there was enough lumber available in Vietnam to support construction, the Cam Ranh peninsula had little flora and that was mostly shrubs. Across the bay were forests that could have supplied some lumber, but this territory had become a sanctuary of the Viet Cong, who used it as a rest area. It would have been expedient to set up a sawmill there, but such an operation, it was feared, would aggravate the enemy and invite serious attack, thus increasing the already demanding security requirements of the engineers. There were too few South Vietnamese military forces nearby to encourage any incursions into enemy areas. As the shortage of lumber continued, all wood the engineers had or could collect went into the most essential projects. It was not unusual for Philippine mahogany plywood, normally reserved for more sophisticated construction, to serve as form lumber in pouring concrete.

The sand also took its toll of the soldiers' energy. Traveling short distances by foot through deep sand could bring on exhaustion. Laboring in daytime heat of 120 degrees, intensified by the reflection from the white sands, soldiers were issued sun helmets and allowed to wear T-shirts at their work. They were platooned into two shifts to take full advantage of the cooler night air. One shift worked from 1 a.m. until 11 a.m. and the second from 3 p.m. to 1 a.m., a schedule that allowed everyone to rest during the hottest hours of the day. Commanders encouraged their men to take salt tablets and drink plenty of water both on and off the job. Still the heat was intense and the dark green tents that were home to the

[44]

PARTIALLY DEVELOPED CANTONMENT AT CAM RANH, JUNE 1966

soldiers on the Cam Ranh peninsula provided little escape from the direct rays of the sun. Only in the tepid waters of the bay immediately adjacent to the established tent city could the troops find relief, and here they relaxed in off-duty time.

Special procedures were developed to combat the intense heat and the damage it could do to construction projects on the beach. Forms were set during the daylight hours, leaving the heavier work of placing concrete floor slabs for the evening hours. This practice served both to protect the men and to insure that the concrete slabs were properly set before the intense heat of the day removed the hydration water.

Upon arrival of the 35th Group at Cam Ranh Bay the demand for fresh water was an immediate problem. Potable water was first obtained by boiling surface water or using simple water purification methods. As soon as conditions permitted, the 35th set up its organic water purification units at a series of springs originally developed by the French. During the first year at Cam Ranh water was also drawn from a trapped lake filled by seasonal runoff from the monsoon rains. This supply was not deemed adequate for

[45]

SANDBAG-REVETTED MACHINE GUN POSITION AT DAU TIENG

long-range use because it lacked a continuous flow of water, making it extremely susceptible to contamination. Ultimately, deep wells were sunk on the peninsula and became the primary source of fresh water for the giant port complex.

All construction at Cam Ranh was organized and directed to meet imposed priorities. The projects of immediate concern on the peninsula were the building of an airfield, assigned to Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen; a rudimentary road network; storage facilities; and the expansion of port facilities. Since the airfield enjoyed the highest priority, the contractor had first call on the unloading of equipment and supplies through the limited port facilities.

To speed the massive earthmoving operations connected with airfield construction, the 35th Group provided training sessions for the Vietnamese operators hired by Raymond, Morrison-Knudsen to drive much of its heavy equipment. From time to time the group also allocated some of its own equipment to assist in the airfield project. A month or two later when Raymond, MorrisonKnudsen fell seriously behind its ambitious schedule and appeared unable to meet the prescribed operational date for the initial airstrip of aluminum matting, identified in military parlance as AM2, the 35th Group was assigned the mission of supporting the contractor through the permanent allocation of two groupings or "spreads" of its earthmoving equipment. In addition, the Army

[46]

engineers helped to install foundations for permanent structures and to build roads. Such cooperative efforts on the part of US Army engineers are sometimes overlooked. It was not unusual for an Army engineer unit to lend assistance to a civilian contractor who needed help to meet an imposed deadline. By the same token the contractor lent assistance to troops from time to time.

The sand at Cam Ranh did serve a useful purpose despite all the problems it caused. The engineers used sandbags in the construction of bunkers, revetments, machine gun positions, and even stairs.

Thus even before construction materials began flowing into the Cam Ranh Bay project, a tent and sandbag city had sprung up on the peninsula. By early July serious work on certain essential projects had begun. The construction of a landing ship unloading site on the beach to relieve port congestion had begun. Temporary motor pools, storage platforms, and a dump for 55-gallon drums of petroleum products were also under way. June of 1965 was for the engineers a month of digging in and tackling the environment at Cam Ranh Bay – the beginning of the long and intricate development of a major logistical complex.

[47]

Go To:

Return to the Table of Contents