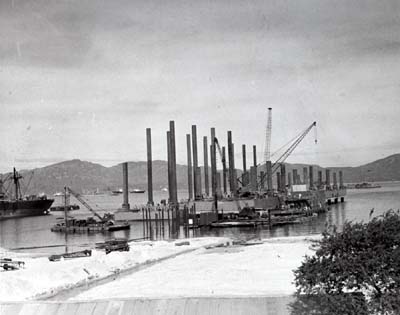

SOLDIERS OF 84TH ENGINEER BATTALION LAND AT QUI NHON

CHAPTER IV

Early Operations

Beginnings at Qui Nhon and Vung Tau

On 11 June 1965 the 84th Engineer Battalion, less Company D, landed at the port of Qui Nhon, capital of the province of Binh Dinh, about halfway between Saigon and the boundary with North Vietnam. The engineers established their base camp in the southern sector of the town and began transporting equipment from ship to shore by amphibious vehicles. Immediate priority was given to the construction of permanent LST beaching ramps and ammunition storage pads. Landfill operations aimed at the development of a depot soon began. At Qui Nhon sand was also a major problem, but it was not so loose as that found at Cam Ranh because here the particles were angular and more evenly distributed as to size. Equipment nevertheless broke down frequently as a result of sand abrasion; what was originally regarded as a healthy stock of repair parts quickly disappeared from the shelves of the maintenance tents.

Rock needed for the construction projects was abundant in a nearby quarry, but before a rockcrusher could be moved to the quarry three miles of access roads and numerous heavy culverts had to be built. To make roads passable the engineers applied layers of the laterite overburden from atop the rock at the quarry as quickly as it could be extracted. A makeshift rock-crushing plant was established to speed production. A lumber retaining wall was constructed with dunnage from the cargo vessels in the harbor, and backfilled with quarry run rock, that is, random-size rocks taken directly from the quarry after blasting. The loading shute to the crusher, erected on a rock-filled crib, consisted of a salvaged 2 1/2-ton dump truck body, the sides of which were extended with channel beams and pierced steel planks to provide an efficient funnel onto the feeder of the crusher. This improvised crusher plant, a tribute to engineer resourcefulness, was the highest volume producer of crushed granite in the Republic of Vietnam until commercial plants reached heavy production levels in late 1966.

On 23 August 1965 the 937th Engineer Group (Combat) headquarters arrived at Qui Nhon and established a base camp adjacent to the camp of the 84th Battalion. On 28 August it took command

[48]

SOLDIERS OF 84TH ENGINEER BATTALION LAND AT QUI NHON

of the 84th Battalion, less company D, relieving the 35th Group of the command responsibility at Qui Nhon.

Company D of the 84th Battalion transshipped from Cam Ranh, arriving at Vung Tau in the south during early June. Unlike the sandy, mountainous peninsula at Cam Ranh, the Vung Tau peninsula was quite marshy. Here, as in Cam Ranh and Qui Nhon, the engineers found few usable facilities. Company D immediately set to work establishing a base camp. The company commander, First Lieutenant Reed M. Farrington, was a Naval Academy graduate who had accepted his commission in the Army. He now found his company charged with developing Vung Tau into a combat support complex designed to relieve Saigon of some of its offloading and storage responsibility. The urgent priority at Vung Tau was the improvement of existing port facilities, which were in a state scarcely deserving of the title. The young commander and his company faced a monumental task in planning, design, and construction.

The design for the depot facilities at Vung Tau had been the responsibility of a contractor working for the U.S. Navy construction agent. When the drawings were 60 percent completed, Lieutenant Farrington discovered that the original terrain analysis had been faulty. A subsurface investigation of the area had not been made, and the design did not take into account the marshy soil

[49]

found at Vung Tau. A redesign was ordered and the 18th Engineer Brigade took responsibility for the task upon its arrival. Although the development of Vung Tau as a staging depot complex was consequently behind schedule, Company D troops continued to work on the port and storage facilities at Vung Tau, getting whatever supplies they could from local resources. These engineers lived in tents on the marshy peninsula and worked with little supervision or support from higher headquarters until the arrival in September at Long Binh of the 159th Engineer Group (Construction). Not until September 1967, when the 36th Engineer Battalion (Construction) arrived at Vung Tau, did the effort there receive significant augmentation.

The most common problems encountered by the first engineer units in Vietnam centered around the shortage of construction materials and the delay in receiving repair parts. Throughout Vietnam, rock was in short supply; lumber and nails were critical items, as were prefabricated buildings and electrical supplies. Some of the most severe equipment shortages were in concrete mixers, rock-drilling equipment, and hauling equipment. Deadline rates on dozers, scoop loaders, and 5-ton dump trucks climbed to alarming heights because of intensive operation, and the slow process of getting repair parts aggravated the maintenance problem. Shortages in repair parts stemmed from the loss of many replacement requisitions in the supply system and a discrepancy between theater assets as they actually were and as they were reflected by Department of the Army agencies. These problems were among the first that faced the 18th Engineer Brigade headquarters upon its arrival in Vietnam in September 1965.

More Engineers Arrive at Cam Ranh Bay

August and September saw the arrival of two more construction battalions as well as three separate companies at Cam Ranh Bay. These were the 62d Engineer Battalion (Construction), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Paul D. Triem, and the 87th Engineer Battalion (Construction), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John J. McCulloch. By Christmas of 1965 the 35th Group had installed a DeLong pier; built roads, warehouses, troop housing, and administrative facilities, hardstands, a jetty for unloading tankers, and a 7.4-mile pipeline from the port to the airfield; and had begun work in Nha Trang, Dong Ba Thin, and Phan Rang.

On 24 August the 497th Engineer Company (Port Construction) arrived with 13 officers and 208 enlisted men. Designed to carry out port and waterfront construction and rehabilitation, the

[50]

company came with a variety of marine equipment and had its own organic diving section. Almost immediately, elements of the 497th began to be shifted from one port to another to lend the necessary expertise to early improvements for ship unloading at Qui Nhon and Vung Tau. The company commander, Captain Paul L. Miles, Jr., became the port construction adviser and consultant for the 18th Engineer Brigade and the headquarters of US Army, Vietnam. His work and that of the 497th became so widely acclaimed and so instrumental in later successes that Captain Miles received the coveted Wheeler Medal of the Society of American Military Engineers for outstanding military engineering in 1965.

In September 1965 Captain Miles and his engineers began preparing for the scheduled arrival in October of the first DeLong pier. For the first time the mobile piers designed and built by the DeLong Corporation were to be committed in support of tactical operations. These quickly assembled piers were to save many valuable man-hours in readying Vietnamese ports to accept the large influx of American war material. At Cam Ranh Bay the first new finger pier accepted deep-draft cargo just forty-five days after the towed pier reached its selected location. Besides preparing for the arrival of the DeLong pier, the 497th was responsible for removing all obstacles from the harbor approaches to the bulkheads or piers under construction, a considerable task since there were many sunken vessels in Cam Ranh Bay.

The diving section of the 497th was frequently called upon for special jobs. For instance it was used in the installation of submarine pipelines at several locations and was detailed to perform propeller maintenance for Transportation Corps vessels docked in the Cam Ranh Bay area. Later the diving section was used in the maintenance of the submarine pipelines and the salvage of sunken Army aircraft. The time spent by the 497th on all these projects jeopardized the successful completion of its primary mission of underwater construction. It was not until the summer of 1966 that the 1st Logistical Command requested a diving section of its own to perform these functions. Until then the 497th continued to provide the requested support.

The first DeLong pier to be sent to Southeast Asia left Charleston, South Carolina, in August 1965. Towed by a tug through the Suez Canal and across the Indian Ocean, the 90x3,000-foot steel pier arrived in Cam Ranh Bay on 30 October after eighty-one days at sea. While the actual emplacement and elevation of the pier barges was performed as requested by Mr. DeLong by his own employees, the Army engineers, particularly those of the 497th Port Construction Company, laid the groundwork for the pier's opera-

[51]

FIRST DELONG PIER UNDER CONSTRUCTION AT CAM RANH

tion. To protect the pier from the effects of beach erosion, the 497th erected a 550-foot sheet pile bulkhead while the 87th Battalion completed a causeway to connect the pier with the beach. The 497th also built a 400-foot timber pier which allowed petroleum products to be transferred directly from ship to shore at Cam Ranh Bay.

Inadequate mechanical lifting equipment, tools, and supplies constantly taxed the resourcefulness of the engineers. The available sheet piling, hurriedly ordered out of Japanese-fabricated stocks, was too short. Many of the fittings and much of the hardware of barges and caissons arrived in poor condition. By repairing or rebuilding vital components of the pier, the men of the 497th were instrumental in its quick installation. The sheet pile bulkhead lasted almost five years before the improvised reinforcing finally failed and parts of the wall collapsed.

It must be recognized that the DeLong equipment by itself could not provide the instant piers sometimes associated with the employment of prefabricated piers. In most instances, complementary construction such as dredging, hydraulic fills, and earth fill causeways was necessary before the piers could be installed and used. All of this was accomplished by Army engineers under difficult circumstances. Technical problems that developed in preparing for the installation of DeLong piers were often solved through the close cooperation between Mr. DeLong and the Engineer Corps command. Information was exchanged readily and

[52]

it was not uncommon for Mr. DeLong, a former engineer officer, to help the Army engineers with equipment from his own reserves. In December of 1965 Secretary McNamara approved the contract negotiation by the Army Materiel Command with the DeLong Corporation calling for the delivery and installation of eight more piers. Since the equal of his corporation's experience in the installation, operation, and servicing of the equipment could not be approached within the military, Mr. DeLong preferred to have his own engineers and technicians install and service his piers.

On 24 August 1965 the 87th Engineer Battalion (Construction), which had been the support battalion for the US Army Engineer School at Fort Belvoir, arrived at Cam Ranh peninsula. After establishing its camp, the 87th was directed to begin construction of a 6,400-man cantonment and a tank farm. It also undertook construction of the 7.4-mile pipeline and a 40x800-foot rock fill causeway with two 80-foot spans of double-single Bailey bridge to connect the DeLong pier with the shore.1 The 35th Group also assigned to the 87th the mission of conducting tests on the relative merits of the various methods used and proposed to stabilize the sand on the peninsula.

Stabilization tests were conducted on the routes to the depot area and to the ammunition supply point. Eight different sections were tested, each 500 meters long and 10 meters wide. In the first trial section sand was mixed in place with cement and measured quantities of water, and the section was compacted and moistened for seven days. The surface thus produced wore rapidly under moderate traffic, but it proved to be satisfactory when used as a base. In the second section 40 percent sand and 60 percent coral fines were combined and mixed in place. The coral was obtained from a single small deposit off the south beach of Cam Ranh peninsula discovered in the exhaustive searches of the 87th Engineer Battalion. After RC3 asphalt treatment of the sand and coral fines only minor deflection and cracking resulted even under heavy traffic. A third section consisted of 40 percent local sand and 60 percent coarse beach sand from the mainland, also treated with RC3 asphalt and then compacted. This section stood up relatively well under light traffic. The fourth section, 40 percent local sand and 60 percent granitic quarry screenings treated with RC3 asphalt, proved as effective as sections two and three, and the material was more readily available. The fifth section, 100 percent dune sand treated with

[53]

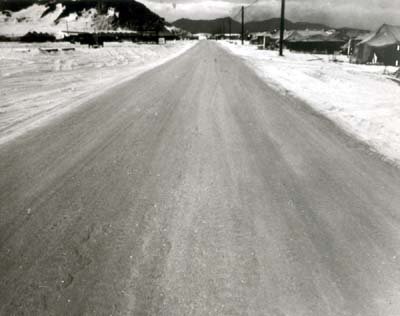

CRUSHED CORAL ROAD AT CAM RANH, built to test road building over unstable

natural sands.

asphalt, was the only section to fail completely. Section six, 100 percent coral fines treated with cement to ten inches in depth and then watered to optimum moisture content, proved to be an extremely strong base course. When protected by a wearing surface, it provided an all-weather heavy-duty road. Section seven consisted of twelve inches of coral fines overlaid with six inches of crushed coral, watered extensively and compacted. This section compared favorably with section six and was less expensive. (The earliest attempt to use crushed coral promised some success.) The road to the ammunition point was later built entirely of this combination. The eighth and last section, made up of decomposed granite and cement to a thickness of eight inches and "moist cured" for seven days, afforded a very substantial base course. Eventually, all depot roads were provided with this base.

The 864th Battalion engineers were working on the depot and by 3 December had erected nine 50x40-foot prefabricated warehouses and had almost completed four 120x200-foot structures. They had begun work on a reinforced concrete automatic data processing center. Company C of the 864th, detached some twenty

[54]

miles away at Nha Trang, was building a tank farm for gasoline and oil, clearing storage areas, and constructing warehouses and cantonments.

On 28 August the 62d Engineer Battalion (Construction) arrived at Cam Ranh from Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and was soon sent to Phan Rang. The process by which the battalion finally reached Phan Rang illustrates the effect of shifts in priorities at the last minute. The 62d had originally been slated to go to the Qui Nhon peninsula; in fact its advance party was already at Qui Nhon when the transport carrying the rest of the battalion reached the coast of Vietnam opposite Qui Nhon. In the meantime, however, a prior decision made in Headquarters, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, for an airfield to be built on the peninsula to the northeast of Qui Nhon harbor had been reversed and the site abandoned as impractical from the point of view of engineering feasibility and security. A proposed airfield at Phan Rang then immediately assumed the highest priority after the one at Cam Ranh Bay. Since no troops had been scheduled to start construction in Phan Rang at that time, the 62d was diverted to Cam Ranh Bay where its equipment was to have been unloaded for transshipment by small water craft to Qui Nhon. However, from Cam Ranh the battalion was routed into Phan Rang, with heavy equipment going over the beach in landing craft and light vehicles going by the road in a series of convoys organized as Operation ESSAYONS. An advance element of the 25th Infantry Division, still in Hawaii, Company C of the 65th Engineer Battalion, which had not yet received its organic equipment and which had landed at Cam Ranh to locate at Dong BA Thin, organized itself in an infantry configuration and provided convoy security. Air cover and surveillance were supplied by aircraft from the 35th Group headquarters. The chief projects of the 62d Battalion were the construction of an aluminum airstrip (AM2), 10,000 feet long and 102 feet wide, as well as a cantonment for incoming Air Force units. Later the 62d was charged with building a base camp for the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, while the division engaged in field operations.

The small Vietnamese village of Dong BA Thin on the western shore of Cam Ranh Bay became the site of a major engineer effort begun by Company C of the 65th Engineer Battalion, which had arrived in early September. The 65th, organic to the 25th Infantry Division, began leaving Hawaii for Vietnam in August 1965. Company C, the first element of the battalion to arrive in Vietnam, worked under the 35th Group until December.

Assisted by elements of the 513th Engineer Company (Dump Truck) and the 584th Engineer Company (Light Equipment),

[55]

Company C was to design and construct an Army aviation base astride the main coastal route, National Highway 1, complete with cantonment areas, heliports, and a runway on what was in essence a swamp. When Company C left the area in late December, it had completed 99 percent of the runway and had made significant progress on many of the other facilities. On 22 January 1966 work was renewed at Dong BA Thin by the newly arrived 20th Engineer Battalion (Combat) under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Richard L. Harris. The 513th Engineer Company and the 584th Engineer Company were attached to and under operational control of the 20th Battalion for the remainder of its time at Dong BA Thin. By May of 1966 the 20th Battalion with its attached units had graded the aviation cantonment area, built seventy-five aircraft parking pads, finished a cargo plane parking area, and begun construction of a taxiway to the completed runway.

As previously indicated, there was no laterite on the Cam Ranh peninsula, but a laterite pit was operated on the mainland across the bay from My Ca. Before the arrival at Cam Ranh of the 553d Engineer Company (Float Bridge) a ferry had made trips rather irregularly across the upper bay at My Ca, a service provided by Transportation Corps units using strike force boats. On 6 October the 553d under the command of Captain Richard L. Copeland inaugurated regular service at My Ca, using a standard 2-boat, 6-float M4T6 pontoon raft augmented by a Navy cube barge powered by sea mules. The new service soon proved unable to cope with the ever-increasing traffic between the peninsula and the mainland. Near the end of November, the 6-float raft was replaced by a "fast ferry" consisting of a much longer M4T6 raft powered by a bridge boat on either side. The bridge boat sideslipped the raft in the direction of its long axis instead of propelling it in the direction of the long axis of the floats. The boats were fastened to the raft by means of a swivel arrangement to facilitate changing direction at each shore. This field expedient permitted the engineers to cope with the steadily increasing traffic for the time being. The fast ferry carried trucks full of the quarried and crushed laterite from the mainland to the peninsula; the quarry became indispensable as a source of laterite for Cam Ranh peninsula.

The 102d Engineer Company (Construction Support) , commanded by Captain Jesse M. Tyson, Jr., was assigned the responsibility of producing asphalt and rock. A unit with this job should have consisted of 6 officers and 158 enlisted men with quarrying, asphalt paving, and other specialized engineer equipment. Captain Tyson and his lieutenants had had no experience in asphalt production, but by making use of the knowledge of some of its non-

[56]

AERIAL VIEW OF MY CA FLOAT BRIDGE, with 10,000-foot Cam Ranh airfield runway

in background. Radio-connected control points at each terminus directed traffic.

commissioned officers the 102d set up a plant and successfully accomplished its mission. The 102d Engineer Company began crushing rock on 3 November to meet the demands of the company's asphalt plant. Soon thereafter the roads on Cam Ranh peninsula took on a new look.

Traffic between the peninsula and the mainland had meanwhile reached the point where the 553d's rafting operation was again inadequate. About half the unit's equipment had been sent to Qui Nhon in support of the 937th Engineer Group. Finally, early in January 1966 the 35th Group received long-sought permission to install a floating bridge. The 39th Engineer Battalion (Combat), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ernest E. Lane, Jr.,2 together with the 553d Engineer Company and the 217th Vietnamese Army Engineer Float Bridge Company, commanded by Captain Ngo Duy

[57]

CONVALESCENT HOSPITAL UNDER CONSTRUCTION AT CAM RANH. Buildings are made

of frame sections, precut and prefabricated on site, and have concrete floors

and sheet metal roofs.

Lam, then proceeded to build the one-lane bridge across the 1,115 foot expanse of the Bay at My Ca. The bridge was assembled into rafts on 6 and 7 January 1966 and installed in sixteen hours on 8 January. The I Field Force commander, who flew over the bridge on 8 January, had flown over the site the day before when there had been no bridge. Upon noticing the newly installed bridge he could only exclaim "Where did that damn thing come from?" Construction of the bridge posed no particular difficulty other than that of devising an anchoring system to cope with reversals in current caused by tide and wind. The participation of Captain Lam's Vietnamese bridge company was essential to the project since the 553d did not have enough bridging to complete the lengthy span, nor could it be accumulated from other points in South Vietnam because of potential tactical demands. Through the kind of ingenuity and resourcefulness reflected above, the complex at Cam Ranh Bay took shape between June and January of the engineers' first year in Vietnam.

The strength of the 35th Group increased greatly on the first day of 1966, when the 20th Engineer Battalion from Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and the 39th Engineer Battalion from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, had arrived at Cam Ranh aboard the USNS Wigle.

[58]

Their arrival enabled the group to accelerate the construction of warehouses, hardstands, and a convalescent hospital north of the airfield complex, and at the same time to provide at least one company in combat support of either the 2d Republic of Korea Marine Brigade at Cam Ranh or the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, at Tuy Hoa. The 102d Engineer Company began improving the internal movement of traffic by producing pavement for the existing roads on the peninsula. The 87th Battalion continued work on cantonments and the connections for the petroleum facilities south of the air base. The 864th continued work on the depot and the automatic data processing facility. By the middle of 1966 Cam Ranh

[59]

Bay was a thriving complex containing even clubs, canteens, chapels, dispensaries, and post exchanges. (Map 4)

Problems of the 35th Engineer Group

The 35th Engineer Group encountered numerous problems during its first six months of operation in the new and hostile environment of South Vietnam. Unforeseen difficulties escalated the cost of engineer troop construction beyond the initial projections. At Cam Ranh peninsula the lack of man-made facilities made it imperative to build necessary troop facilities, thus delaying the construction of the more sophisticated logistic complex. Construction was not the expedient type acceptable for tactical situations; structures had to be built carefully and solidly to endure the harsh environment for an extended time. The lack of ground lines of communication between commanders and their units caused extraordinarily heavy reliance on air and sea lines of communication, the use of which was time consuming and costly. The attempts to isolate the war from the "normal existence" of the Vietnamese people to the greatest extent possible caused tactical and logistical headaches for all American forces.

Shortages in electrical power were an early problem for American forces throughout South Vietnam, where the demand for power was unusually great. The hot, humid climate made refrigeration vital and air conditioning more a necessity than a luxury. Refrigeration was required for a multitude of things from medical supplies to flashlight batteries. Air conditioning became almost as necessary for the men working inside the sweltering administrative buildings.

Other problems were those of funding and the initial policy of single-item requisitioning insisted upon by the US Army, Pacific, Inventory Control Point. Use of the peacetime procedures of programming, justifying, and accounting for funds reduced engineer capacity at the foxhole and bulldozer level. The US Army, Pacific, policy of single-line requisitioning did not insure the most timely supply of construction materials. For example, if base development plans called for the construction of a particular type of cantonment, each item necessary to construct the facility had to be requisitioned as a distinct piece of material. Such a system was in marked contrast to a bulk requisitioning system keyed to bills of materials for pre-engineered facilities that could have provided at one time all materials necessary to construct a cantonment of the size and standard specified in the requisition.

Commanders at all levels were forced to turn their attention to base development planning. At the group level the task at first

[60]

EROSION CONTROL AT DONG TAM in the delta where sandbags and burlap treated

with peneprime (asphalt derivative) were used.

seemed too large for the organization. Staff officers were obliged to concentrate on construction already in progress and had little time to devote to long-range planning. Nevertheless, planning sections were established and well-conceived base development plans were devised to guide construction throughout the group's area of responsibility.

To help alleviate the manpower shortages during the early phases of the mammoth construction program in Vietnam, engineer commanders sought to hire skilled laborers from the indigenous work force. But the predominantly agricultural economy of South Vietnam had not produced many men with the technical skills required in so many branches of construction. The few skilled workers that were available had been snapped up by civilian contractors before the Army engineers were committed to the struggle. Although the 35th Group did manage to find and employ a few experienced draftsmen, most of the Vietnamese hired were common laborers. To overcome this shortage in technical skills, training programs were instituted at various unit levels to teach new skills

[61]

to the local Vietnamese and to develop those skills through experience gained on the job. Two ends were thus served. Overburdened engineer commanders benefited from a competent work force, and previously untrained Vietnamese acquired skills that would serve them and their country after the Americans were gone.

A shortage of handling equipment at the 53d Engineer Supply Point Yard caused long delays in the off-loading and distribution of needed materials. In addition, advance reports of incoming shipments were inconsistent and misleading, and the officer in charge of construction found it impossible to plan or schedule the necessary construction operations. Construction projects were often delayed because appropriate construction materials were not available.

In the process of building on Cam Ranh peninsula, insufficient attention was given the existing ground cover. In clearing and leveling work sites the first US engineers removed the scanty scrub cover. Later, in November, the monsoon season brought serious erosion. The heavy rains frequently washed out completed work and roads, and the fierce winds drifted the sand like snow. These problems were later minimized by selective planting of grass and the erection of snow fences.

The year 1965 saw the number of engineer troops in Vietnam increase from less than a hundred to more than seven thousand. The 35th Group landed on a bleak sandy peninsula in June, and by December had effectively "tamed the sands at Cam Ranh Bay." It was also a year of learning. The problems encountered were many and varied, but the Army engineers proved that they could adapt to their new environment.

[62]

Go To:

Return to the Table of Contents