Chapter II:

Logistics Environment

To understand the problems and conditions that characterized the logistical effort in Vietnam, one must keep in mind the sequence of events during the early buildup period. The speed and magnitude of the escalation of U.S. combat troop deployments in response to enemy action and pressure proceeded faster than a logistic base could be developed to support these units. The Republic of Vietnam had a low level of industrialization. Modern logistic facilities were limited or nonexistent. The in-country logistic system supporting the South Vietnamese Armed Forces was incapable of supporting major U.S. forces. The small, highly fragmented system supporting the U.S. advisory effort could do no more than provide the skeleton for a later logistical system. The enemy controlled the major part of South Vietnam, either by direct occupation or through terror tactics. The principal terrain features as well as land and water arteries were either under enemy control, or subject to the constant threat of interdiction.

Logistics planning was further complicated by the fact that logistic troops and units were deployed at about the same rate as tactical forces rather than in advance of them as desired for the timely establishment of an adequate logistic base. The chronology of U.S. unit arrivals in the Republic of Vietnam shows a continuous inflow of detachment- and company-size logistical support units during practically every month of the period spring 1965 to summer 1966. In addition, logistics units were deployed on a Technical Service basis (Table of Organization and Equipment) whereas the new Combat Service to the Army doctrine had already been approved, thus causing much agony. Meanwhile, major tactical forces, to include the bulk of the 1st Infantry Division; the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) ; the 173d Airborne Brigade; the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division; and the 3d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division (which was later to become the 3d Brigade of the 4th Infantry Division) were in-country and engaged in battle by January 1966. The major part of the 25th Infantry Division had arrived by April of that year and brigade-size elements arrived practically every month during the period August-December 1966, to include elements of the 4th, 25th, and 9th Infantry Divisions,

[8]

as well as the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, and the separate 19th and 199th Light Infantry Brigades. The remaining brigade of the 9th Infantry Division arrived in January 1967. Meanwhile, further deployment decisions were made, and the Americal Division, the 101st Airborne Division (-) , and other units appeared in Vietnam during the period September 1967 to March 1968.

Logistic Concept (1965) and In-Country Planning

As early as 1962, the need for a centralized U.S. logistical organization in South Vietnam was foreseen by Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Lieutenant General Paul D. Harkins. The proposal was disapproved, however by Commander in Chief U.S. Army Pacific and Commander in Chief Pacific, who felt that the requirement was not justified at that time. The idea was revived in August 1964 by the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, J-4, who believed that the current and future situation would require a logistical command to support activities in South Vietnam. Accordingly, he saw that a plan was prepared which included the prompt introduction of a logistical construction capability. On 21 December 1964, the joint Chiefs of Staff endorsed the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, plan and recommended that 230 men be initially dispatched to South Vietnam to form a logistical command as soon as possible. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara approved the plan in principle, but stated that additional justification was needed, particularly for the engineer construction group. However, he felt that the subject was of sufficient importance to send a special representative to South Vietnam, and on 31 January 1965, a group from the Office of the Secretary of Defense arrived in Saigon. After four days of conferences, this group recommended the establishment of a logistical command with an initial strength of 350 men. The establishment of an engineer construction group, not recommended initially, was approved in April as planning for a further buildup developed.

On 25 February 1965, the' Secretary of Defense approved the introduction of a logistical planning group in the Republic of Vietnam consisting of 17 officers and 21 enlisted men. Colonel Robert W. Duke was en route to take command of the 9th Logistical Command in Thailand. He was intercepted in Hawaii and ordered to the Republic of Vietnam to take charge of the planning group. He arrived in Saigon on 6 March 1965. The balance of the officers and enlisted men for the planning group arrived in Saigon during the last two weeks of March 1965. On 1 April 1965, the 1st Logistical Command was activated in Saigon by Commander in

[9]

Chief U.S. Army Pacific General Order, using the personnel of the logistical planning group as its initial strength.

Prior to this time, logistical support in Vietnam had been fragmented, with the Army providing only Class II and IV items which were peculiar to the Army, Class V items used by the Army aviation units, and maintenance of vehicles, armament, and instrument calibration by a small Direct Support shop in Saigon. The rest of the support was provided by the Navy through Headquarters Support Activity, Saigon because the Navy had been designated as the executive agency responsible for supporting the Military Assistance and Advisory Groups and missions in Southeast Asia.

The mission of the 1st Logistical Command as developed by Colonel Duke and the initial small planning group was, in broad terms, that the 1st Logistical Command would assume responsibility for all logistical support in Vietnam, less that which was peculiar to the Air Force or Navy. This initial mission included procurement, medical, construction, engineer, finance and accounting of all U.S. Army forces in-country, except Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, advisors; and excluded communications, aviation, and military police support which were retained by U.S. Army Vietnam (the Army component command under Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and over the 1st Logistical Command). Requirements beyond direct support and general support maintenance capability were to be retrograded to Okinawa. Subsequent add-on missions were planned to be put into effect as the capability became available. These add-on missions were to: assume support of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, advisors from Headquarters Commandant, Military Assistance Command Vietnam, a task accomplished on 1 September 1965, phase-out the Navy supply activity in Saigon-The 1st Logistical Command started assuming Headquarters Support Activity Saigon functions in September 1965, and completed the mission in March 1966-and assume common item support for all U.S. Forces in South Vietnam.

The 1st Logistical Command was authorized direct communications with U.S. Army Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa) on logistic matters. Logistic requirements were placed there. After screening, requirements were filled or passed to U.S. Army Pacific. It either filled them or passed them to Army Materiel Command. This proved to be very unsatisfactory due to inadequate electrical communications with Okinawa, lack of adequate stocks and personnel resources in Okinawa as well as U.S. Army Pacific, and the many headquarters in the logistic chain. Through this chain there was a

[10]

loss in excess of 40 percent of all requisitions submitted in the initial stages of the buildup. A combat area should be able to submit requisitions directly to Continental U.S. Continental U.S. could then direct shipment to the combat area from the nearest source to that area having the required items in stock.

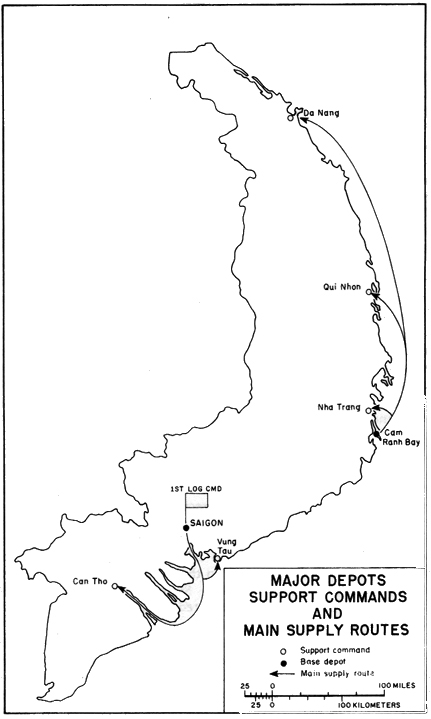

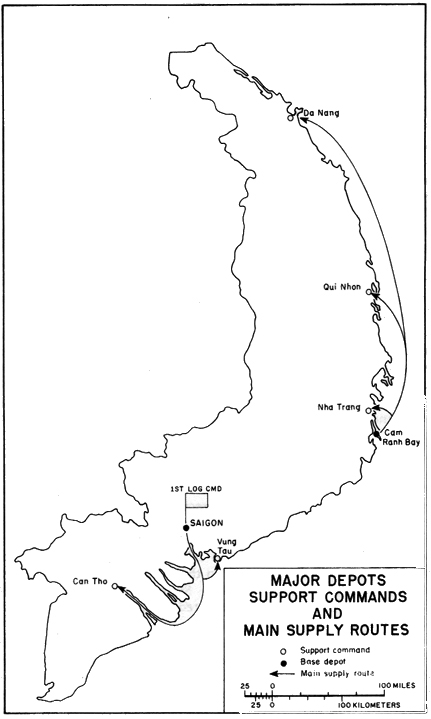

The 1st Logistical Command, in coordination with Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, operational planning, developed its own logistic concept for South Vietnam. The plan provided for two major base depots and five support commands. (Map 1) The seas and rivers were initially to be the main supply routes within Vietnam. However, a change over to road and rail would take place when the tactical situation permitted. Each support command would provide all logistic support on an area basis and have a 15 day stockage. Depots would have a 45 day stockage. The Saigon Depot would support the Vung Tau and Can Tho Support Commands. The Cam Ranh Bay Depot would support the Nha Trang, Qui Nhon and Da Nang Support Commands.

A two depot concept was considered essential due to the vulnerability of the Saigon River and port to Viet Cong action and the limited port capacity. Vung Tau was considered an alternate to the Saigon port in the event of loss of Saigon or blockage of the Saigon River. Cam Ranh Bay was selected as the other base depot and port due to its excellent deep water harbor, the existing pier, its central location, and U.S. capability to secure the area from Viet Cong attack.

This plan by the 1st Logistical Command was implemented with only two changes; the Marines were landed at Da Nang and, by Commander in Chief Pacific direction, the Navy was given the responsibility for both tactical and logistical operations in I Corps. The Da Nang Support Command was eliminated from the 1st Logistical Command plan. It was reinstated in 1968. The anticipated scale of tactical operations in the Delta area of IV Corps did not materialize, so the Can Tho Support Command was not activated. The IV Corps was supported by the Vung Tau Support Command by sea and air.

The original plan for the refinement of a logistical plan in an orderly fashion followed by a deliberate and orderly implementation never came to pass. Instead it quickly turned into a concurrent planning and implementation process. The Secretary of Defense approved at the 9-11 April 1965 Hawaiian Conference an Army Combat force of over 33,000 troops with the first combat troops (173rd Airborne Brigade from Okinawa) to arrive in South Vietnam on 21 April 1965. This was just the beginning of the ac-

[11]

[12]

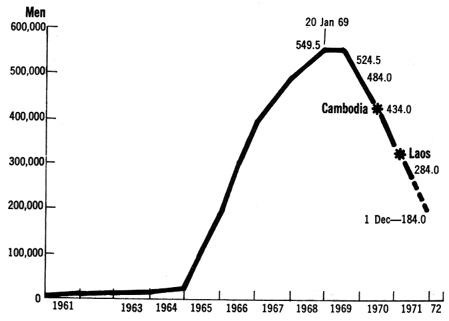

celebrated buildup. (See Chart 1 and Table 1.) After the April conference there were a series of other force level planning conferences in Hawaii, at which Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, would request forces that were required. However, the number of troops approved by the office of the Secretary of Defense was always less than the number requested by Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

U.S. Forces were built up in an imbalanced manner. Continued enemy pressure on the beleaguered government of South Vietnam and manpower ceilings combined to cause the logistics base to be inadequate in relation to the total force level.

Each time a new ceiling was established it was announced as a final ceiling

and could not be changed. Therefore, all planning for future operations had

to be based on this number, including requests by the Office of the Secretary

of Defense to Congress for supporting funds. This series of "final ceilings,"

and the decision not to call up a large number of Reserve Component units, established

a pattern of "too late planning," and "too late determination

of requirements" that affected every facet of the military establishment

from draft quotas to administration, training, equipping, procurement by Army

Materiel Command, Defense Supply Agency, and Government Services Administration.

This resulted in a drawdown of reserve and project stocks to an unacceptable

level.

CHART 1 - AUTHORIZED TROOP LEVEL IN SOUTH VIETNAM

[13]

TABLE 1-U.S. ARMY AND TOTAL U.S. MILITARY PERSONNEL IN SOUTH VIETNAM

| Date | U.S. Army Personnel | Total U.S. Military Personnel |

|---|---|---|

| 31 Dec 1960 | 800 | 900 |

| 31 Dec 1961 | 2,100 | 3,200 |

| 31 Dec 1962 | 7,900 | 11,300 |

| 31 Dec 1963 | 10,100 | 16,300 |

| 31 Dec 1964 | 14,700 | 23,300 |

| 31 Mar 1965 | 15,600 | 29,100 |

| 30 Jun | 27,300 | 59,900 |

| 30 Sep | 76,200 | 132,300 |

| 31 Dec | 116,800 | 184,300 |

| 31 Mar 1966 | 137,400 | 231,200 |

| 30 Jun | 160,000 | 267,500 |

| 30 Sep | 189,200 | 313,100 |

| 31 Dec | 239,400 | 485,300 |

| 31 Mar 1967 | 264,600 | 420,900 |

| 30 Jun | 285,700 | 448,800 |

| 30 Sep | 296,100 | 459,700 |

| 31 Dec | 319,500 | 485,600 |

| 31 Mar 1968 | 337,300 | 515,200 |

| 30 Jun | 354,300 | 534,700 |

| 30 Sep | 354,200 | 537,800 |

| 31 Dec | 359,800 | 536,100 |

| *31 Jan 1969 | 365,600 | 542,400 |

| 31 Mar | 361,500 | 538,200 |

| 30 Jun | 360,500 | 538,700 |

| 30 Sep | 345,400 | 510,500 |

| 31 Dec | 330,300 | 474,400 |

| 31 Mar 1970 | 321,400 | 448,500 |

| 30 Jun | 297,800 | 413,900 |

| 30 Sep | 295,400 | 394,100 |

| 31 Dec | 250,700 | 335,800 |

| 31 Mar 1971 | 227,600 | 301,900 |

| 3 Jun | 197,500 | 250,900 |

* Indicates peak strength in South Vietnam

Between 1954-1960 U.S. Military Strength averaged about 650 advisors

The first US Army combat unit to arrive in South Vietnam (173rd Airborne Brigade) was employed in the Saigon area to insure retention of Bien Hoa Airfield and to assist in securing Saigon. It was initially supported directly from Okinawa by a daily C-130 aircraft flight. Later the support was assumed by the 1st Logistical Command.

[14]

The second combat unit to arrive was the 2d Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division. Plans called for their employment at Qui Nhon to secure that area for future use. From the meager logistic resources in South Vietnam some were deployed to Qui Nhon to support that unit. Due to the buildup of enemy pressure on Saigon, Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, made the decision two days before the arrival of the 2d Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division that the 2d Brigade would be employed in the defense of Saigon. This resulted in a scramble to relocate the few U.S. supplies and ammunition in South Vietnam from Qui Nhon south some 250 miles to Saigon. Numerous changes were made in tactical plans in the initial stages of the buildup due to Viet Cong pressure. Such changes were necessary, but had an adverse effect on orderly logistical planning and implementation.

As logistical units arrived in South Vietnam they were assigned to appropriate depots or Support Commands as the tactical situation directed. In all Support Commands small units and detachments arrived ahead of the command and control units. As a result officers from the seventeen-man officer staff of the 1st Logistical Command had to be sent to the Support Command areas to receive, organize, assign missions, coordinate efforts, and command these small units and detachments pending arrival of a command and control headquarters. As an example, a U.S. Army major with a jeep and a brief case was the complete command and control unit for the Saigon area. This included finding and securing living areas and work areas for arriving units. Prior to June 1965, the 1st Logistical Command operated on a very thin shoestring. As more staff officers and command and control units arrived in June the command and control situation improved greatly.

On 11 May 1965, the Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and his staff were briefed on the logistic plans of the 1st Logistical Command. This briefing included real estate requirements and requirements for tactical troops for depot and support command areas at Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, and Cam Ranh Bay. The plan was approved on 12 May 1965. The first ship unloading operation at Cam Ranh Bay took place on 15 May 1965. Since Army stevedores had not yet arrived in South Vietnam, and the South Vietnam stevedore union refused to send civilian stevedores to Cam Ranh Bay, the first ship was unloaded by a U.S. transportation lieutenant and a small group of enlisted men assembled through levies on units for anyone with any stevedore or small boat experience. From such a start Cam Ranh Bay was built up to a major and efficient port.

[15]

With the arrival of combat forces and the 1st Logistical Command becoming operational, its small staff could not accomplish all the planning that was required. A request was placed on U.S. Army Pacific for assistance. U.S. Army Pacific then provided five officers on a 90 day temporary duty tour. These officers reported to the 1st Logistical Command on 23 April 1965 and were given the task to make a study of the Qui Nhon enclave, Nha Trang enclave, and the Cam Ranh Bay area, to determine the tactical security requirements and the feasibility of utilizing these areas as included in 1st Logistical Command's concept, and to refine the logistics planning for each area to include base development.

These planners prepared a study which proved to be of great value in base development and the expansion of the 1st Logistical Command's capabilities. This study with appropriate recommendations and requests for tactical troops for security of desired areas was presented to the Commanding General U.S. Army Vietnam and Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in May 1965. Approval was received and security was provided as requested at each location, except Qui Nhon. General Westmoreland approved the security plan for Qui Nhon, but due to Viet Cong pressure and a shortage of U.S. forces the implementation of the plan was delayed over a month. Even then the forces available were not able to push out and secure all of the originally planned areas. This left the ammunition depot at Qui Nhon exposed to enemy action.

Upon completion of the enclave study, a new problem faced the planning group. It was recognized that the continued influx of troops into the city of Saigon (10,000 in the next 4 months) would soon exceed its capability to absorb. It was also recognized that usable real estate and facilities were not available in the Saigon area. A threefold mission was given to the planning group: develop a short range plan to absorb the influx of troops into the Saigon area, develop a long range plan that would ultimately move the bulk of U.S. Army personnel out of the Saigon area, and develop detailed plans for the security and logistical development of the Can Tho areas.

A thorough reconnaissance was made and chosen areas were selected. In order to relieve the pressure on Saigon facilities, the Long Binh area was selected for the establishment of a major logistical and administrative base. A master base development plan was prepared which provided areas for all activities in Saigon.

General Westmoreland (who was both Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and Commanding General

[16]

U.S. Army Vietnam) was briefed on the study and approved it in principle, except he elected to move Headquarters U.S. Army Vietnam to Long Binh (Headquarters Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, remained in the Saigon area). The 1st Logistical Command immediately began implementing the study by locating the ammunition depot, hospital, engineers, plus direct support and general support supply and maintenance support at Long Binh. The movement of headquarters type activities was delayed by the requirement for $2 million to develop an adequate communication system in the area and by the time required for installation of the system.

The study on Saigon proved to be of great value. Long Binh became a major installation in the Republic of Vietnam. The study on Vung Tau and Can Tho resulted in the elimination of Can Tho as a support command. The delta area was supported from Vung Tau and Saigon. The Vung Tau portion of the study included plans for the development of Vung Tau as a deep draft port utilizing De Long piers.

Major Logistics Constraints

To the logistician, it is extremely important to have an early decision establishing theater standards of living. These standards should determine the basic authorization for post, camp, and station property, PX stockage of merchandise, whether base camps are to be constructed, construction standards, the degree of permanency for fixed installations, and utilities and services to be provided. Obviously, such a decision has a tremendous impact on the logistic system. Construction materials alone constituted some 40 percent of total tonnage of materials coming into South Vietnam in 1965 and 1966.

Without such established standards to use as terms of reference, it was impossible to realistically determine requirements for such items as real estate, supply, storage, maintenance, construction, electricity and other utilities, as well as the resultant port unloading capability required. Without such standards, the logistic system has no grounds for challenging requirements placed upon it. Such a decision was never made in the early days of Vietnam. Therefore, every unit independently established its own standard of living, ordering from supply catalogs as if they were Sears and Roebuck catalogs. Commanders desiring to give their personnel the very highest possible levels of comfort and quality of food, requisitioned air conditioning and refrigeration equipment far in excess of that authorized by Tables of Organization and Equipment. This had a

[17]

mushrooming effect. Requirements for electrical power generating equipment were in turn increased to the point that demand exceeded the capability of Tables of Organization and Equipment authorized equipment. As the requirement for this equipment increased, the numbers of makes and models proliferated (as suppliers of standard makes and models were unable to keep up with the rapidly increasing demands). As the quantities of equipment increased, so did the requirements for repair parts and qualified maintenance personnel. The repair parts were a problem because of the many varied makes and models and the resultant lack of interchangeability among their parts. It was difficult to maintain full Tables of Organization and Equipment authorized maintenance strength much less the numbers of personnel required to maintain the excess equipment. Therefore, because these personnel were not readily available in sufficient quantities, back-up equipment was requisitioned (for emergency use) further burdening an already heavily taxed logistic system. Finally decisions were made on a piece-meal basis on such things as construction standards. But even with established standards, there was flexibility in interpretation. More often than not, the interpretation did not favor the most austere construction or equipment requirements. This not only put a heavy burden on the logistical system, but it also taxed the Continental U.S. troop base which was not structured in numbers or skills to support the construction or equipment installation and subsequent maintenance requirements which evolved from the Vietnam buildup.

War Reserve Stocks

The stocks available in March 1965 were totally inadequate. For example, only one DeLong pier was available while a dozen could have been used. The timely availability of these piers would have saved the government large sums of money in ship demurrage and speeded up the buildup of forces.

Logistical Management Organizations

Logistical management organizations were not available. As an example, it was a year before a supply inventory control team arrived in South Vietnam. By the time it had become operational, its equipment was found to be inadequate and had to be upgraded. This same situation was common in other areas of logistical management. In a new theater of operations under combat conditions, there is a pressing need early in the operation for manage-

[18]

ment organizations to be completely mobile, automated, and self-supporting. Further, these early logistics management organizations and units were Technical Service oriented even though the Combat Service to the Army functional doctrine had been approved. Difficulties were experienced in fitting the Technical Service organizations into the new doctrine that had not been fully tested before Vietnam.

Engineer Construction

As the buildup progressed, it became apparent that the engineer construction program was becoming so large it required a special command to oversee it. In July 1965, the decision was made to deploy an engineer brigade to the Republic of Vietnam, and upon its arrival the engineer construction functions were transferred from the 1st Logistical Command to the Engineer Brigade.

With increased combat requirements, the priority for logistics construction projects declined for a period and the construction of essential port and depot facilities fell behind schedule, adversely affecting the capability to handle incoming troops, equipment, and supplies. However, in December 1965, Commander in Chief Pacific directed that the highest priority be given to port and beach clearance and depot construction. After this the capability to handle incoming cargo steadily improved.

Logistic Support Principles

The organization for supply support followed the area support, "logistical island," concept with the sea being the main supply route. Field depots were established in each support command to receive, store, and issue Classes II, IV, VII and IX items, less aviation, avionics, medical, and missile peculiar items. The depots provided area support as indicated below:

1. The 506th Field Depot, Saigon (later US Army Depot, Long Binh) was responsible for III and IV Corps.

2. The 504th Field Depot, Cam Ranh Bay (later US Army Depot, Cam Ranh Bay) was responsible for the southern part of II Corps.

3. The 58th Field Depot, Qui Nhon (later US Army Depot, Qui Nhon) was responsible for the northern part of II Corps.

4. The US Army Field Depot, DaNang was established on 25 February 1968 with the mission of supplying Army peculiar items

[19]

in I Corps. This depot operated as a field depot of the Qui Nhon base depot.

Virtually all Army tactical operations received logistics support from 1st Logistical Command elements operating logistical support activities located at major base camps such as Tay Ninh, Bearcat, Phuoc Vinh, Can Tho, Pleiku, An Khe, and Chu Lai. When forces beyond the reach of these facilities required additional support, temporary forward support activities were deployed.

Initially, medical services and medical supply were organic to the 1st Logistical Command mission. As the buildup progressed, the magnitude of the medical mission became greater. A decision was made to transfer this function from the 1st Logistical Command to a medical brigade. The 44th Medical Brigade assumed this function upon arrival in South Vietnam in 1966.

Aviation logistic support was initially provided by the U.S. Army Support Command, later U.S. Army Vietnam. The 34th General Support Group (aviation supply and maintenance) was deployed to South Vietnam in mid-1965 to manage this function.

The Logistical Support Activity was a continuing provisional activity composed of 1st Logistical Command elements and generally located in a fixed base camp to provide direct and general supply, maintenance, and service support to U.S. and Free World Military Assistance Forces on an area basis. The type and number of units comprising a Logistical Support Activity was dependent upon the scope of the support mission. Many of these operations involved substantial portions of either a supply and service battalion, direct support maintenance battalion, or elements of both with the senior officer present serving as the Logistical Support Activity commander. Stockage levels of all classes at a Logistical Support Activity were determined by the densities of personnel and equipment supported, considering replenishment capabilities. Stockage objectives for the various classes of supply varied from 5 to 45 days depending upon the commodities being stocked.

A Forward Support Activity was a provisional organization, temporary in nature, and deployed in the vicinity of a supported tactical unit's forward operating base to provide direct supply, maintenance, and service support. It was deployed to support a specific tactical operation, when the tactical organic support capability was not sufficient to provide the support required. Upon completion of the operation, it was withdrawn from the area of operations, and its assets and personnel returned to their parent unit. Personnel and equipment comprising a Forward Support Activity were drawn from Tables of Organization and Equipment

[20]

and Tables of Distribution and Allowances units assigned to the parent Support Command of the 1st Logistical Command. Forward Support Activities could stock Class I, III, V, and limited, fast moving Class II and IV, if the tactical unit was unable to provide their own support. Stockage levels were set at a minimum level consistent with operational requirements (based on troop and equipment densities, resupply rates, capacity and consumption experience). Throughput was used to the maximum extent possible to replace stocks consumed at Forward Support Activities. Maintenance and services were provided as required depending upon the supported unit's organic capabilities, tactical deployment, and densities.

If a Forward Support Activity became a continuing activity, it was usually redesignated as a Logistical Support Activity. Normally, a Forward Support Activity which continued operations over six months was redesignated as a Logistical Support Activity.

The concept of using a Forward Support Activity to provide combat service support was developed due to the particular environment in South Vietnam and the manner in which tactical units operated. Brigade-size units were engaged in search and destroy operations which in many cases were conducted in areas located a considerable distance from their base camp and major support installations.

The 1st Logistical Command did not have separate authorization for the personnel and equipment required to operate Forward Support Activities, although the need for such authorization existed. Personnel and equipment were drawn from Tables of Organization and Equipment and Tables of Distribution and Allowances units assigned to the parent support command or were provided by the other support commands when the requirement exceeded the parent support command's capability. The initial Forward Support Activity concept envisioned the organization and fielding of Forward Support Activities in support of tactical operations of short duration. Experience showed, however, that some Forward Support Activities were required for extended periods of time resulting in a degradation of the capability of the units from which personnel or equipment were drawn.

Establishment of permanent brigade base camps and the deployment of non-divisional. Tables of Organization and Equipment supply, service, and maintenance units to these areas reduced the requirements for Forward Support Activities. In many locations where Forward Support Activities originally provided support, it was possible later to provide logistical support by a Logistical

[21]

Support Activity with composite support organizations providing tailored supply, service, and maintenance support on an area basis. Then when brigades were deployed outside of their normal area of operations, in most cases, it was possible for the tactical units to obtain support in their new area from combat service support units in that area. When required, augmentation of Tables of Organization and Equipment support units in forward areas enabled a direct support maintenance battalion, for example, to provide across-the-board logistical support to all divisional and non-divisional units in its area of responsibility. Although the requirement for operation of Forward Support Activities was significantly reduced, each Support Command maintained on-call a Forward Support Activity (by specifically designated personnel and equipment) capable of rapid deployment when a Forward Support Activity was required by tactical units. The implementation of the Forward Support Activity and Logistical Support Activity concept enabled tactical commanders to concentrate on their primary mission while ranging deep into enemy territory. These commanders knew that the required logistical support would be available whenever and wherever required.

As the buildup progressed, the technology for the management of supplies improved and new and imaginative concepts and procedures were developed. The period 1965-1966 was characterized by fifteen months of unprecedented growth and development. Inheriting a fragmented logistics structure consisting of some 16 different systems managed by separate component services, U.S. Army Vietnam and the 1st Logistical Command pulled these systems together to form a unified structure. However, even then it was not feasible to combine all aspects of support into one command. In this period, the 1st Logistical Command managed all logistics and support functions for U.S. Army Vietnam except for aviation supply, maintenance support, and engineer construction. The logistics island concept and Logistics Support Activity and and Forward Support Activity support concepts were developed, and three major support commands were established at Saigon, Cam Ranh Bay, and Qui Nhon. Major port and depot construction was undertaken in each area to support the hundreds of thousands of combat and logistics troops entering the country. In late 1965, the control of stocks in storage and on order was accomplished by a laborious manual process. Each depot was considered a separate entity and requisitioned replacement supplies directly through 2d Logistical Command in Okinawa. Under this system, there was no practical accountability of total in-country supply levels. In

[22]

less than three years, this process was replaced by a complex control system involving the large-scale use of electronic computers. Coincidentally, procedures were evolved to provide continuous and up-to-date inventory accounting of all stocks within Vietnam. In late 1967, a fully automated central inventory control center was established at Long Binh (handling all type of supplies, except ammunition, aviation, medical and special forces items), and was known as the 14th Inventory Control Center.

Modern computer equipment was installed in the 14th Inventory Control Center to attempt to bring some order to the supply chaos in the depot stock inventory. The major problem encountered was the tremendous influx of supplies which were over the beaches and through the port flooding the depots under a massive sea of materiel and equipment much of which was unneeded. Push supplies and duplicate requisitions of thousands of tons of cargo piled up in the depots, unrecorded and essentially lost to the supply system. In the latter part of 1967, control was slowly established over the requisitioning system through the use of automation and the flow of unneeded supplies abated somewhat. Through these improvements in control and accountability, in-country requirements could be tabulated, interdepot shortages and excesses balanced, and requisition priorities evaluated.

In the pre-buildup stage, most cargo destined for Vietnam was shipped directly from Continental U.S. depots and vendors to west coast military sea or aerial ports. From these ports it was loaded aboard ships or aircraft and moved either to Vietnam directly or to Okinawa which provided backup support. Cargo shipped directly to Vietnam, for the most part, was initially received at the Saigon water port or the Tan Son Nhut airport. Military cargo was treated very much as commercial or Agency for International Development cargo, with little emphasis on specialized development of surface or air distribution methods, facilities, or equipment.

Between mid-1965 and late 1966, cargo continued to move primarily by ship. Airlift was used to move the great majority of troops and priority cargo, which accounted for only a small part of the total tonnage moved. Surface cargo, during this period, continued to flow to Okinawa, Vietnam and Thailand causing multiport discharging, although efforts were made to direct shipments to the final destination port.

Initially, most waterborne cargo arriving in South Vietnam was received at the Saigon Port, the only port with deep draft piers

[23]

except for a small two-berth pier at Cam Ranh Bay which had been constructed in 1964 under the Military Assistance Program. The Saigon Port was a civilian port under the management control of the Republic of Vietnam's governmental port authority. It consisted of ten deep draft berths. U.S. Army cargo was unloaded by Vietnamese civilian stevedores at berths assigned by the civilian port authority. Coordination of military cargo unloading and port clearance was handled by the Navy's Headquarters Support Activity Saigon.

When the buildup began, the port continued to operate in this fashion. Headquarters Support Activity Saigon never knew from day to day how many berths or which berths would be made available to them for the unloading of U.S. cargo. In addition, customs at the Saigon port dictated that cargo discharged from ships be placed on pier aprons to await port clearance by the cargo owner. It was up to the consignee to remove the cargo from the port. Cargo not consigned to U.S. Forces remained on the piers for weeks and sometimes months, creating undesirable and crowded working conditions which adversely affected port operations. Repeated efforts to get South Vietnam to clear the piers were unsuccessful. Some of the cargo being received by South Vietnam was U.S. Military Aid equipment which became South Vietnam equipment as it was unloaded. U.S. Forces were accused many times of improper port clearance because this equipment was olive drab in color. But such equipment frequently proved to belong to South Vietnam and the U.S. Army had no authority to move it.

The overloaded port facilities and the operational necessity to selectively discharge cargo to get high priority cargo ashore before less urgently required items resulted in excessive ship turn-around time which increased the total number of ships required. This situation was complicated as cargo was manifested by broad categories only, for example, general cargo, making it impossible to locate specific items. Holding the ships for lengthy periods resulted in demurrage charges of from $3,000 to $7,000 per day per ship. Also the inadequate and insecure railroads and highways forced the distribution system to rely heavily on shallow draft vessels for transshipment of cargo between the Saigon Port and other locations, and intratheater airlift between Tan Son Nhut air terminal and other locations. The problem was further aggravated by a shortage of shallow draft vessels both military (LCMs and LCUs) and civilian assets, which were used for offloading cargo from deep draft vessels at ports not having adequate berthing facilities for the larger ships. Civilian lighterage as well as military

[24]

landing craft, primarily LCMs and LCUs were used for this purpose.

The U.S. Army's 4th Transportation Command arrived in South Vietnam on 12 August 1965. It was given the mission of assisting Headquarters Support Activity Saigon in U.S. port operations and assuming that function completely as soon as possible, which it did in September 1965. In addition, it was charged with providing technical assistance to port and beach operations at Cam Ranh Bay and the support commands being established throughout South Vietnam. As U. S. Army terminal service companies were received, they were initially employed in unloading of ammunition at Na Bhe, the central ammunition receiving point just south of Saigon, and were later employed in Saigon proper. In May 1965, a request was made to the government of the Republic of South Vietnam to acquire the three Maritime Marine piers adjacent to the Saigon port facilities for the exclusive use of U. S. Forces. These facilities were owned by a French shipping firm. This request ran into financial and political difficulties, but was finally approved in December 1965 after the personal intervention of General Westmoreland and the U. S. Ambassador. With the exclusive use and control of these facilities, port operations improved in efficiency and volume. The delay in obtaining these piers plus the shortage of yard and storage space and the lack of a depot structure and accounting procedures prevented the early establishment of adequate port facilities.

Nevertheless, it was apparent that additional port facilities would be required in the Saigon area. The 1st Logistical Command made this known to Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, who directed his staff to develop plans for the facilities now known as Newport. Construction began on this fifty million dollar facility in early 1966. In April 1967, the first deep draft vessel was discharged at the Newport facility. Also, during this period, several other ports throughout Vietnam were in the construction phase.

By the end of December 1967, the ports in use by the Army numbered 10; Saigon, Qui Nhon, Cam Ranh Bay, Vung Ro, Vung Tau, Cat Lai, and Nha Trang were the deep draft ports; Dong Tam, Phan Rang and Can Tho were the shallow draft ports. These improvements in port capabilities brought about a reduction in the average time a deep draft ship waited for a berth in Vietnam ports from 20.4 days during the most critical period of 1965 to the 1970 average of less than two days.

[25]

Warehousing and Storage Facilities

Prior to the buildup, warehouses and storage areas were literally nonexistent, except for limited facilities in the Saigon area. Supplies were scattered in several locations throughout Saigon, all of which were substandard and overcrowded; some were only open storage. At the time the 1st Logistical Command became operational, there was a construction backlog for the troops already in country. Construction of logistics facilities competed with many other requirements. Since there was never more than $300 million in annual capability to apply against a total theater program of close to $2 billion, the construction effort took almost six years to accomplish.

To initially offset this shortage of facilities, negotiations were initiated with the United States Overseas Mission to obtain 13 Japanese built warehouses with dirt floors and no electrical wiring in the Fishmarket area in Saigon. Three of these buildings were obtained by the end of 1965 and the remaining 10 during 1966. A contract was also let to construct an added 210,000 square feet of covered storage and to fill an area behind the warehouses that would serve as hardstand for open storage and a troop cantonment area. This area housed the 506th Field Depot until a new depot was constructed in Long Binh in 1968 and the move to the new facilities was completed 1 July 1969.

By way of comparison, the new depot facilities at Long Binh provided 1,869,000 square feet of black-topped hardstand and 1,458,000 square feet of covered storage, whereas the depot facilities at the Fishmarket in Saigon had a total of only 670,000 square feet of covered storage space as late as March 1967.

Additionally, agreement was reached with the United States Overseas Mission on 16 March 1965 to provide and erect some prefabricated buildings owned by the United States overseas mission for use as warehouses in the Qui Nhon, Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay, Nha Trang, and Saigon areas. These buildings were finally available for occupancy in February 1966, almost one year after the agreement. The same basic situation prevailed at Qui Nhon where substandard and overcrowded facilities were occupied until completion of the new depot at Long My in 1968.

The United States constructed a major depot and port complex at Cam Ranh Bay costing over $145 million, $55 million of which came from Army appropriations. Cam Ranh Bay was an undeveloped area located at an excellent natural harbor which when completed had over 1.4 million square feet of covered storage, 1.2 million square feet of open ammunition storage area, and bulk storage facilities for over 775,000 barrels (42 gallons per

[26]

barrel) of- petroleum products. Construction of this complex was started early in the buildup period when it was envisioned that the main war effort would be along the Cam Ranh Bay-Ban Me Thuot-Pleiku axis. Since the war activity took place to the North (Qui Nhon and Da Nang) and South (Saigon), the depot was not utilized to the degree the planners originally anticipated. As a result, there are some who claim that the war passed Cam Ranh Bay by. When taken in that particular context, there is some truth to the claim.

Even though war activity took place in areas different from those expected, Cam Ranh Bay played an important role in the logistics picture. A U.S. Army Support Command was established there as a major logistical command and control element, the Korean forces were supported almost exclusively from Cam Ranh Bay throughout the time they were in the II Corps Area, transshipping supplies from ocean going vessels to coastal type shipping was accomplished there, and marine maintenance was done there. The excellent and secure ammunition storage areas permitted keeping large stocks of needed ammunition in-country relatively safe from enemy attack and the cold storage facilities permitted fresh vegetables to be brought down from Dalat and stored properly till distributed to our forces. Also having a major storage and shipping facility close to the major air base operated by the Air Force was a distinct advantage. At one time it was planned to move the Headquarters of the 1st Logistical Command there (it was later decided that the 1st Logistical Command and Headquarters U.S. Army Vietnam should remain near Headquarters U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) and until fairly late in residual force planning, Cam Ranh Bay was going to remain as a major U.S. logistic complex. This too was dropped in favor of the Saigon-Long Binh area.

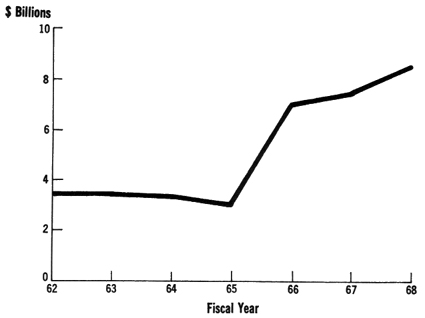

Continental U.S. Production Base

At the time the Vietnam buildup began, the Army's industrial base was operating at a relatively low level. This can be seen from a comparison of the Procurement of Equipment and Missiles for the Army contracts awarded before and after the buildup began. (Chart 2)

Procurement and receipt of equipment lagged behind the increase in Army strength during the buildup. The lag in production resulted in inadequate quantities of equipment being available to supply all worldwide needs. Extraordinary actions and management techniques were used to obtain the maximum benefits from the 1965 inventory and assets being produced. These are covered

[27]

CHART 2 - PROCUREMENT OF EQUIPMENT AND MISSILES FOR THE ARMY CONTRACT AWARDS

in greater detail in other sections, but in general, items critically needed in Southeast Asia were taken from reserve component units and active Army units not in Southeast Asia, and new issues of certain items of equipment in short supply were centrally controlled by Headquarters, Department of the Army.

There were four main reasons for production lagging behind equipment and supply requirements:

1. A planning assumption that all hostilities would end by 30 June 1967. During 1965, President Johnson announced the buildup of forces in South Vietnam. The Army immediately updated its existing studies to ascertain the ammunition posture-both the availability of world-wide assets and the U.S. Army Munitions Command's capability to support combat operations from industry production. These updated studies became the basis for the supplemental fiscal year 1966 budget programs. The fiscal year 1967 Army budget was restated on the assumption that Vietnam support would continue only through June 1967. Because of this assumption, many planned mobilization producers were not interested in bidding. Due to production lead times involved, they would be reaching peak rates at the time production supposedly would be cut back. Also more profit could be derived from the manufacturer's production of consumer goods.

[28]

2. The lack of a full mobilization atmosphere precluded the full employment of the Defense Production Act of 1950 (as amended). Since the U.S. itself was not imminently threatened, it was not felt appropriate to create a crisis situation among industry and the populace. Therefore, the powers granted by Congress in the Defense Production Act of 1950, which permit the Government to direct civilian industries to manufacture those items needed for national defense in preference to civilian oriented items, were used very sparingly. This meant that in many cases civilian industries were unwilling to undertake the manufacture of defense oriented items at the sacrifice of interrupting their supply to a flourishing civilian market. However, in the cases where it was deemed necessary to employ provisions of the Defense Production Act, the problems were resolved effectively.

3. The "No Buy" restriction placed on the procurement of major items of equipment for temporary forces (units that were to be manned only for the duration of the Vietnam conflict) by the Office of the Secretary of Defense constrained Procurement of Equipment and Missiles for the Army programs. These procurement restrictions actually made it necessary for certain of these units to borrow equipment that had been purchased for other units or for reserve stocks. This resulted in a lessening of the readiness posture of the unit or reserve stocks for which the equipment was originally purchased.

4. For some specialized and often high priced items there was frequently only one source of procurement. This "sole source" was a hindrance to rapidly increasing the quantities of the items available. The production facility manufacturing a particular item, in some cases, could not increase its production fast enough to meet the rapidly rising military requirements. Also, some manufacturers did not deem it feasible to expand their production facilities, at great expense, to meet temporarily increased sales to the government. In addition, for the same reason, new sources of supply were not easily convinced to enter into production of these items.

The industrial base utilized by the Army consists of both government owned and privately owned production facilities including real estate, plants, and production equipment. Private industrial facilities are of primary importance and are only supplemented by the Army's resources. However, Army owned facilities are required to produce military items having no significant commercial demand. Accordingly, the Army has throughout its history maintained varying capabilities for production, mostly in the munitions area.

[29]

Prior to the buildup for Southeast Asia, only eleven of twenty-five Army owned munition plants were operating. Immediate actions were taken to activate whatever additional ammunition plants were required to support the anticipated consumption. Six ammunition plants were activated in fiscal year 1966; six more were activated in fiscal year 1967; and the last plant required to meet production requirements was activated in fiscal year 1968. Only one government owned munition facility remained inactive.

One important factor in the rapid improvement of the ammunition production base was the special emphasis given to Munitions. During the latter part of 1965 when the increased tempo in Vietnam made it apparent that ammunition was going to be required in larger quantities than the post-Korea stocks would support, the Secretary of Defense established a relatively small organization to control air munitions. Shortly thereafter it was suggested to the Secretary of the Army that he establish a similar organization to control ground munitions. The organization was activated in the Army Secretariat and staffed by requesting people with the required expertise. On 15 December 1966, the Office of Special Assistant for Munitions was established in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics and at that time the Army Secretariat relinquished the responsibility and the authority to the Army staff. However, a close relationship existed between Office of Special Assistant for Munitions, the Army Secretariat, and the Ground Munitions Office in the Office of the Secretary of Defense because of the intense interest in the ammunition program. This interest stemmed from the high dollar value of the program and congressional concern over ammunition matters. Eventually the Office of the Special Assistant for Munitions became a Directorate within the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics known as the Office of the Director of Ammunition.

Logistic Personnel and Training

During the period 30 June 1965 through 30 June 1967 a total of 1,057,900 personnel entered the Army and losses totaled 584,500. The resulting numerical turnover of personnel exceeded the Army's peak strength. Of the total gains, 977,000 were new accessions with no prior military experience (616,600 draftees; 360,400 first term enlistees) . Another 80,900 were procured from other sources such as reenlistees within 90 days of discharge. While the Army's total strength was expanding by almost 50 percent, its monthly loss of trained personnel averaged over 24,000. These losses created turbulence, denied the Army the use of immediately

[30]

available trained skills, and required that over one million men and women be brought on duty to achieve an increase in overall strength of less than 4'74,000. Replacing skilled individuals with personnel of like skills was a serious problem. The Army was faced not only with the problem of training thousands of personnel with entry-level skills, but also had to provide additional training in lieu of skill progression normally acquired by on-the-job experience.

One of the most significant factors contributing to the personnel turbulence throughout the Army was the one-year tour for personnel assigned to South Vietnam. In late 1965, to avoid 100 percent rotation of men in a unit in Vietnam at the end of their 12 month tour, the Army applied personnel management techniques to insure that not more than 25 percent of a unit would be rotated in any one month. These techniques included tour curtailments, short extensions, exchanges of troops with other similar units, and voluntary extensions of individuals.

The rapid buildup, coupled with the twelve-month tour of duty, made the replacement program a problem of great magnitude. The regular replacement of personnel in the short-tour areas came close to representing a complete annual turnover. Rotation after a year boosted individual morale, but it also weakened units that had to send experienced men home. Further, personnel turnover often invalidated training previously accomplished by a unit. A large portion of the Army's enlisted requirements is in skills that are not self-sustaining because the requirements for them in long-tour areas are inadequate to provide a rotation base for short-tour areas. The advantages in morale outweighed the disadvantages cited, but the drawbacks to short tours were there and cannot be glossed over.

In many cases, support personnel assigned to Vietnam did not have the essential experience in such areas as depot operations, maintenance, and supply management. There was a shortage of junior officers and senior non-commissioned officers who had the logistics experience necessary to supervise "across the board" logistics for brigade size tactical units at isolated locations. Many of the supervisory personnel did not have any experience or training outside of their own branch and were assigned duties and responsibilities above that normally expected of their grade.

Logistic support units deployed to Vietnam were deficient in unit training. Of significant impact upon mission accomplishment was the method by which the support units were trained in the early 1960s. With reorganization from the technical service con-

[31]

cept to the Combat Service to the Army concept, functional training of units was decentralized in the Continental Army Command to post, camp and station level. There were no Quartermaster, Ordnance, or other titular heads looking after the training of their units. This condition fostered a haphazard incorporation of current doctrine and procedures in training which was already decentralized.

A program was initiated at Atlanta Army Depot to provide on-the-job training in depot operations for selected enlisted personnel en route to U.S. Army Vietnam. From 1967 through 1970, 4,619 enlisted personnel received this training.

Other special training programs were established to provide orientation and training for selected officer personnel at the Defense Supply Agency Depot at Richmond and at the U.S. Army Electronics Command, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey.

Beginning in June 1968, the 1st Logistical Command initiated some fairly extensive training courses in South Vietnam. Project SKILLS was introduced to provide orientation, indoctrination, specialist training, and on-the-job training on a recurring basis at all levels of command. SKILLS I ALPHA was a detailed orientation and indoctrination of newly assigned colonels and higher key staff officers and commanders at battalion or higher level, Department of the Army civilians of equivalent grade, and command sergeants major. SKILLS I BRAVO was a formal orientation and indoctrination for enlisted specialists newly assigned to elements of the command.

SKILLS I CHARLIE was an orientation, indoctrination, and formal continuing on-the-job training of all enlisted personnel. With the increasing role of local nationals in the 1st Logistical Command, the need for a local national training program was recognized and Project SKILLS II was initiated. This program was designed not only to help get a job done, but also to contribute to the self-sufficiency of the Republic of Vietnam in the future.

The trained personnel shortage was also alleviated somewhat by the arrival in-country of Program Six units which were force packages consisting of Army, Reserves, and National Guard combined by Department of Army and containing many highly educated personnel who possessed critical skills.

Strategic Army Forces were tapped to meet Vietnam personnel requirements. The primary mission of Strategic Army Forces is to maintain combat readiness to respond to contingencies on a worldwide basis. In April 1965, a substantial drawdown of Strategic Army Forces personnel began. At that time approximately one third of the command was composed of logistic and administrative

[32]

personnel. This was not a balanced force, and under the impact of drawdowns, the percentage of logistic and administrative personnel remaining in Strategic Army Forces units was reduced further to approximately one-fifth by the end of Fiscal Year 1966. Unit readiness was further degraded by drastic imbalances in enlisted grades and military occupational specialties. Logistical activities in South Vietnam often experienced shortages of personnel with specific skills and technical training. In some cases, skill categories were deficient in the numbers required because of the civilianization of Continental U.S. military activities and the constant decline in the retention rate of experienced military personnel. Concurrent with the decision not to call the Reserves was the determination to continue normal separations. Consequently, discharges at the end of periods of obligated service, resignations, and retirements were continued as in peacetime. The Army was most severely restricted by this policy. There were shortages of officers in all grades except lieutenant. U.S. Army Europe was also called on to provide many trained troops and specialists with critical skills in the combat service support for South Vietnam. As a result, combat unit personnel in U.S. Army Europe were diverted from their intended assignments to perform maintenance, supply, and housekeeping tasks. Tour length policies and worldwide distribution of structure spaces caused an enlisted skill imbalance between short tour areas and the rotation base. For certain skills (for example helicopter mechanics, electronic maintenance, and supply personnel) the preponderance of structure spaces was in short tour areas.

The percentage of support personnel versus combat personnel in South Vietnam fluctuated. Early in 1965 the percentage of support personnel was estimated by some authorities to be as low as 25 percent. At that time supply lines of communication were not as long as they later came to be. In 1966, as supply lines of communication had lengthened and a major effort was underway to alleviate the congested ports and depots, the percentage increased to approximately 45 percent. By 1969, at the height of our troop strength, the percentage of support personnel had dropped to 39 percent. However, this percentage rose again as our strength reductions continued and a greater percentage of combat forces were withdrawn. For example, by the end of March 1971, the ratio of personnel had changed to 53 percent combat and 47 percent support due to the requirement for support personnel to retrograde materiel of the departing combat units. These support percentages include only military personnel. In addition to

[33]

these personnel, civilian workers and contracting firms were employed for many support services throughout the Vietnam operation.

In viewing the above percentages, it is important to remember that the classification of Army units as either combat or support is not clearcut, and the definitions of these categories are subject to varying interpretations. For example every infantry unit includes administrative personnel whose mission is something other than combat with the enemy; and every supply company contains truck drivers or helicopter pilots who travel daily to the combat zone where they are subject to hostile operations and contacts. With these qualifications in mind, we generally classify the total strength of each division, plus all other infantry, armor, artillery, and certain aviation, engineer, and signal units as combat forces. All other types of units (for example maintenance, supply, military police, medical, and transportation) are classified in the support category.

The force structure of the active duty components of the Armed Forces must be designed to permit adequate logistic support of ready forces in quick reaction to emergency situations. During peacetime, emphasis was in some cases placed on the maintenance of combat and combat support forces without adequate combat service support units and trained technical personnel. As a consequence, when contingency operations are undertaken and the Reserves are not called up, serious deficiencies in logistic units and trained logistic personnel may be expected. There is a need, therefore, to enhance readiness to respond promptly to limited war of scope comparable to the Vietnam conflict without reliance on national mobilization or callup of Reserves to conduct logistic operations.

Logistic security, including the physical protection of logistic personnel, installations, facilities, and equipment was one of the more critical aspects of the logistic effort in Vietnam. Ambushes, sapper and rocket attacks and pilferage caused logistics commanders to be constantly aware of the necessity for strict security measures. The tactical situation was not always evident or given consideration during the installation construction planning phase. There were no "secure" rear areas. Often planning personnel did not fully appreciate the tactical situation, and some installations were constructed at the base of unsecured high ground, making

[34]

the dominant terrain feature a prize for the enemy for observation purposes as well as offensive action.

Personnel and equipment authorizations for logistic organizations were inadequate for the additional mission of security. Radios and field telephones were in short supply. These items were essential to the security of the installation perimeter, including the bunkers, towers, patrols, "sweep teams", and reaction forces. Night vision devices helped but were not available in adequate quantities.

Pilferage and sabotage were prevalent at many installations. Some of the means utilized by commanders to minimize these actions are listed below:

1. Frequent inventories were taken.

2. Continuous employee education was conducted.

3. Physical barriers with intrusion delay devices and detection aids were employed.

4. Employee identification badges were used to control access to various controlled areas, as well as the installation itself.

5. Access to storage areas for highly sensitive items were strictly controlled.

6. Management techniques such as spot inspection, spot searches of personnel, and bilingual signs warning personnel against infractions of rules or theft were used to insure understanding by workers.

7. Strict controls were implemented on receipts and transfers of cargo between ports and the first consignees. Transportation Control and Movement Documents were used extensively for the transfer of cargo from one storage area to another.

8. On sensitive items such as those highly desired by the enemy, markings were subdued or obliterated, to prevent identification by the enemy, and in their place "U.S. Government" was stenciled. In subdued or obliterated markings, the federal stock number had to remain visible and legible.

9. Twenty-four-foot-high anchor fences were used around petroleum, oils, and lubricants tank farms to improve security from sapper attacks and other sabotage efforts by the enemy.

10. Practice alerts were conducted frequently to assure that all personnel were familiar with their defensive assignments within the perimeter in case of an enemy attack.

Convoy commanders were continually faced with security problems in the movement of cargo from one location to another over the insecure highway system in Vietnam. Support from artillery

[35]

fire support bases and medical units, and military police escorts were arranged when such was available.

The compelling need to move cargo dictated the "do it yourself" principle. To help combat the lack of security in this type of operation, and to monitor the shipments in an effective way, many safeguards were initiated. Military drivers and trucks were used to haul post exchange and other sensitive supplies or readily marketable commodities. Trip ticket controls, road patrols, check points, radio reports of departures and arrivals, and strict accounting for loading and offloading times were used. Close liaison with Vietnamese law enforcement agencies along the truck route was established. Armed security guards were utilized to reduce the effectiveness of enemy ambushes.

To offset the shortage of armored vehicles available for convoy escort, transportation units devised the expedient of "hardening" some cargo type vehicles. The beds of 5-ton trucks were usually floored with armor plate and sandbagged. The sides and front of the trucks were also armor plated. The trucks were usually equipped with M60 and 50 caliber machine guns. One gun truck was assigned to accompany about ten task vehicles in a convoy. In 1968 the V-100 armored car was sent to South Vietnam and was exceptionally useful when available for convoy security. Helicopter gun ships were used to maintain aerial surveillance of convoy columns. In addition to providing the surveillance function and a rapid means of response to an enemy attack, these gun ships presented a visible deterrent to the enemy. Clearing of roadsides and paving road surfaces to make mining more difficult and mine detection easier increased security.

Of special help to the logistic commanders were the combat arms officers on the U.S. Army Vietnam and the Support Command staffs who advised and assisted them on security matters. With their guidance, logistic commanders were able to improvise within their own resources and provide an acceptable degree of security.

Despite the various obstacles involved, the logistic security mission was in most cases effectively accomplished. Convoys delivered their cargos, and defensive measures at logistic installations repeatedly frustrated enemy attacks.

[36]

page created 2 January 2003