Chapter III:

Supply Support In Vietnam

For the first time in modern history, the U.S. Army was required to establish a major logistical base in a country where all areas were subject to continuous enemy observation and hostile fire, with no terrain under total friendly control. There was no communications zone; in fact, combat and communications zones were one and the same, and the logistics soldier was frequently and quite literally right with the front line tactical soldier. There was no meaningful consumption and other experience data upon which to base support estimates. As a result, there was an initial influx of huge quantities of supplies of every description to support the tactical troop buildup. This occurred well before the availability of either a logistic base or an adequate logistical organization.

Adding to the difficulties in 1965 was the fact that the supply systems then being used in the United States were either automated or in the process of being automated. Personnel were being trained in automated supply procedures. But going into Vietnam the way we did meant going in with light, non-automated logistic forces. Actually the Army didn't have the computers and technological skills to support the buildup with an automated supply system. Initial operations in Vietnam involved the use of a manual system for in-country support. The interface between these systems, which relied heavily upon punch card operations, and the more computerized wholesale systems, posed difficulties until in-country mechanization was expanded.

During the initial year and a half of manual operation, the sheer volume of traffic and the inability to interface with the automated Continental U.S. systems resulted in an almost insurmountable backlog of management problems that required two years to untangle. Even though UNIVAC 1005 card processors were installed in the depots in 1966-67 and replaced with IBM 7010/1460 computers in 1968, the lead time associated with the approval process, construction of facilities, writing and debugging computer programs, and making the system operational was such that, by the time a new system was on line, it was barely adequate to cope with the continually increasing requirements.

[37]

Automatic Data Processing System capability for logistic management must be introduced in a combat theater as soon as possible with adequate communications support and with the capability of interfacing with Automatic Data Processing Systems outside the combat area.

By 1968 there was an automated supply system operating in Vietnam. Even at the direct and general support level there was automation to some degree. At this level there were NCR 500 computer processors to compute repair parts requisitioning objectives and dues-in and dues-outs.

Repair parts (Class IX) supply was especially interesting due to . the fact that the number of items authorized for stockage mushroomed from an insignificant number in 1965 to 200,000 in October 1966 and then was reduced to 130,000 in May, 1967 and to 75,000 by March 1971. Besides a monumental bookeeping exercise, there were other dynamics in the system. We had to automate so that we could manage.

To get items in-country that would be needed by the arriving forces, Push Packages were used initially. The purpose of this method of supply was to provide a form of automatic resupply to meet the anticipated consumption and to support the prescribed load lists, and the authorized stockage lists of committed units until normal requisitioning procedures could be established. In June 1965, when the use of Push Packages began, all types of supply items were included, but by January 1966 Push Packages contained only repair parts.

Among the factors entering into the decision to use Push Packages were:

1. Theater prestockage had not been effected when the Vietnam buildup commenced except for limited U.S. Army Pacific war reserve prepositioned equipment in Okinawa and elsewhere.

2. The long order and shipping time from Continental U.S. to Vietnam precluded the use of normal requisitioning procedures.

3. The rapid introduction of a large number of combat units into Vietnam was accompanied with an entirely inadequate number of supply support units and logistic supervisory personnel. Supply support units, such as Direct Support Units and General Support Units which would normally have carried the authorized stockage for supporting the combat units were not available in South Vietnam.

[38]

4. The tactical concepts of air mobility to be employed in Vietnam dictated the immediate availability of repair parts for the great density of helicopters and other types of equipment.

5. Engineer and service type units that were initially employed anticipated an early need for repair parts due to the primitive areas in which they would be operating and the resultant high intensity of equipment usage.

6. Procurement of military supplies was not possible on the Vietnamese economy.

Packages were made up for all large units and for small units when combined troop strengths reached approximately 5,000. These packages were shipped to Vietnam in various increments. The supplies included in each incremental package were developed from National Inventory Control data. The first two increments were shipped directly to the designated unit or force, while the remaining increments were intercepted at the depots responsible for supporting the unit or force. The composition of each supply package was of necessity determined from data not associated with Southeast Asia operations. World War II and Korean experience was all that was available. As a result, in some cases the packages proved to be unbalanced in relation to demand, causing overages in some items and shortages in others.

Nevertheless these automatic resupply packages served a very definite and useful purpose in supporting the initial buildup of combat troops in Vietnam, particularly during 1965 and early 1966. Without this form of resupply, we would not have been able to support our combat troops within the time frame that we did. The success of the Push Packages is attested to by the fact that no major combat operation was ever delayed or hampered by a lack of supply. A number of problem areas were encountered, however, which included:

1. The inability of inexperienced unit supply personnel to sort, identify, and properly issue the volume of items received. In many cases, the original Push Packages and their individual contents were identifiable only by shipment numbers and Federal Stock Numbers. Therefore, highly skilled supply personnel were required for placing these items in the proper bins to make them readily available for use.

2. A lack of secure warehouse and storage space and sufficient logistic units at depots. The size of individual Push Package increments arriving in Vietnam initially was too large for the discharge capacity, storage facilities available, and the capabilities of the supply units at the unloading areas.

[39]

3. In some cases, unit destinations were changed without changing the destination of the Push Package causing a delay in the receipt of the package by the intended unit.

4. Inexperienced personnel became accustomed to the "push" philosophy and failed to evaluate measures for transition to the normal "pull" system. As a result of the dependence upon external assistance, units failed to maintain effective demand data or to initiate measures which would permit stockage at intermediate support levels.

Because of the problem areas encountered, supplies in many cases were available in-country, but could not be identified or located. For example, in mid-1966 (even in 1968) some of the original Push Package supplies still remained in the depots, unbinned, unidentifiable and unusable for the purpose for which they were shipped. This factor together with the overages resulting from unbalanced packages had the net effect of generating excess supplies in various locations in Vietnam.

In future operations, Push Packages may again be required for initial or special supply support. These packages, as proven by experience, must be developed on an austere basis and include plans which permit transition to normal supply support. Push Packages should be based on the latest experience factors available and should be scrubbed to exclude those items which are "nice to have." Push Packages should make maximum use of standard containers with stocks prebinned and accompanied by locator cards. These packages should also contain prepunched requisitions to be introduced into the system in order to establish support stocks at theater level. Push Packages should be approved only as an interim relief measure which permits the pull system to again respond to the unit's needs.

On 10 June 1966, as a result of conferences, communications, and experience gained during the buildup, Department of the Army dispatched a message to U.S. Army Pacific and Army Materiel Command setting forth an automatic supply policy and procedure which stopped Push Packages and started the process of normalizing supply support. Essentially supply support of all forces was to be provided through normal requisitioning procedures within U.S. Army Pacific, and Army Materiel Command was to provide equipment density data for projected deployments to provide an order-ship lead time in excess of 195 days.

Exceptions to the above, were a 90 day package of high mortality repair parts for the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, support for new items of equipment introduced into Vietnam,

[40]

and for any unscheduled arrivals. These exceptions were considered on a case-by-case basis. Falling into the latter category were the 9th Infantry Division and the 196th and 199th Infantry Brigades. However, by January 1967 their stockage position and supply management capability had improved to such a level that U.S. Army Vietnam advised that Push Packages were no longer required for these units. U.S. Army Vietnam requested that any further preparation on movement of such packages be discontinued unless they specifically requested or concurred in such shipment.

| Packages | Increments | Line Items | Units | Days of Supply |

$-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-A | 8 | 51,000 | Log Sup | 120 | 8,745,664 |

| 2 | 15 | 24,000 | Inf Bde | 240 | 21,066,321 |

| 3 | 15 | 24,000 | Airborne Bde | 240 | 19,629,691 |

| 4-A | 15 | 75,000 | Airmobile Div | 240 | 89,329,697 |

| 4-B | 15 | 78,000 | Airmobile Sup | 240 | 26,956,335 |

| 4-C | 15 | 59,000 | Corps Sup | 240 | 12,367,475 |

| 5 | 14 | 133,000 | Inf Div | 210 | 73,182,715 |

| 8 | 14 | 115,000 | Combat Sup Log & Adm | 210 | 47,163,539 |

| 9 | 14 | 156,000 | Combat Sup Log & Adm | 210 | 59,397,912 |

| 10 | 14 | 50,000 | Combat Sup Log & Adm | 210 | 10,194,865 |

| 11 | 4 | 16,000 | Combat Sup Log & Adm | 210 | 3,497,674 |

| 12 | 4 | 21,000 | Combat Sup Log & Adm | 210 | 4,461,050 |

| 15 | 1 | 12,335 | 25th Div-1st & 2d Bde | 60 | 611,414 |

| 16 | 1 | 11,279 | 25th Div-3rd Bde | 60 | 588,039 |

| 17 | 1 | 16,904 | 25th Div (Minus) | 60 | 1,546,430 |

| 18 | 1 | 8,253 | 4th Inf Div | 60 | 1,047,092 |

| 19 | 1 | 3,732 | 11th Arm Cav Div | 90 | 931,187 |

| 20 | 1 | 2,823 | 196th Bde | 90 | 253,840 |

| 21 | 1 | 5,430 | 9th Inf Div | 90 | 1,342,413 |

| 22 | 1 | 2,950 | 199th Inf Bde | 90 | 215,897 |

| Total | 155 | 865,706 | 382,529,250 | ||

| Cam Ranh Bay | |||||

| XZJ | 1 | 50,321 | Depot Stocks | 60 | 6,411,744 |

| YUH | 1 | 15,200 | Hawk Missile Bn | 90 | 1,500,000 |

| 2 | 65,521 | 7,911,744 | |||

| Grand Total | 157 | 931,227 | *390,440,994 |

*Equivalent of 195,220 short tons.

The above tabulation (Table 2) of Push Packages shipped to Vietnam indicates packages shipped, number of line items, and dollar value of each package. Also shown are two special

[41]

applications of Push Packages-the Cam Ranh Bay Depot Stock package and the special package for a Hawk battalion.

As a result of Vietnam experience, U.S. Army Materiel Command automatic supply procedures have been revised. The selection of support items is equipment oriented, rather than force oriented and employs the principle of repair by replacement of components and modules (Contingency Operations Selection Technique) . Also, a technique has been developed for the predetermination of austere, essential requirements for automatic supply support of type units to permit effective planning for receiving, storing, and handling materiel incident to unit deployment. Another procedure has been adopted which provides for the computation of requirements for support stocks based upon existing deployable divisions rather than type forces (Contingency Support Stocks) . Still another technique, under continuing review and refinement, calls for the containerization of minimum essential items of materiel needed to support specific quantities of an end item for a specific period (Container Integrated Support Package). The matériel included in such support packages would be identified and binned within the containers to facilitate receipt, storage, issue, and replenishment actions.

Earlier it was noted that equipment to support our forces was produced after the need or requirement was apparent. Naturally there were shortages. And the lag between the establishment of requirements and the availability of sufficient assets existed right up to 1971 for some items. To satisfy the requirements for forces being sent to Vietnam and for the replacement of combat and other losses, equipment was withdrawn from and denied to the rest of the Active Army and Reserve components. Some items became so critical that their allocation was controlled by the Department of the Army through the application of intensive management techniques.

Satisfying the need for items in short supply was a different process for each item. Eight situations for eight different classes or types of equipment follow for illustrative purposes.

Armored Personnel Carriers

It wasn't easy to satisfy the requirements before 1967, but from 1967 through 1969 the demand for armored personnel carriers in U.S. Army Vietnam jumped dramatically. Tables of Organization

[42]

and Equipment requirements increased approximately 124 percent, while at the same time new operational uses were causing greater exposure and increased battle losses. To reduce losses, overhaul was increased; and to minimize shortages, assets were withdrawn from lower priority units worldwide. Early in 1967, Army Materiel Command began developing a belly armor for armored personnel carriers to reduce damage and casualties caused by mines. A mine protection kit was developed consisting of belly armor, rerouted fuel lines kits, and non-integral fuel tanks. By mid-March 1969, U.S. Army Vietnam had tested the first belly armor and it was enthusiastically accepted by commanders and crews. U.S. Army Vietnam asked for expedited procurement to equip all their armored personnel carriers, since high battle losses were projected and the kits had proven to be effective in reducing losses.

In August 1967, it was decided that conversion of the armored personnel carrier fleet from gasoline to diesel power was necessary to reduce the danger of fire after suffering enemy caused damage. At that time, 73 percent of the armored personnel carrier fleet in U.S. Army Vietnam was gasoline powered. An intensive effort was made to equip the entire U.S. Army Vietnam fleet with diesel engines. All new diesel production was allocated to Southeast Asia; however, high losses and increased deployments exceeded the production rate. It was 1 July 1968 before the total armored personnel carrier fleet in U.S. Army Vietnam was equipped with diesel engines.

Beginning in April 1967, a Closed Loop Support program was developed to retrograde armored personnel carriers needing repairs, repair them, and return them on a scheduled basis. New techniques were developed in the repair of battle damaged vehicles in which damaged sections of hulls were cut out and replaced. Plans were made to expand Sagami Depot, Japan to cover the requirements of the Eighth Army, U.S. Army Vietnam, and the Republic of Vietnam Army. Production schedules were increased and a maximum effort was exerted to recruit additional personnel. Starting in 1969 Sagami was able to support the U.S. Army Vietnam rebuild requirements thereby enhancing supply performance.

Ground Surveillance Radars

The AN/TPS-25A ground surveillance radar became a critical combat support item in 1968. It had proven to be very successful in locating personnel moving at night in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta. Since it had not been produced since 1959, the with-

[43]

drawal of the assets from other major commands and Reserve Components was necessary. The overhaul and shipment of the radar sets to meet U.S. Army Vietnam's total requirements was completed in August 1969.

In order to maintain the inventory of radars in Vietnam at a high state of operational readiness, they too were included in a Closed Loop Support Program reducing total requirements through the integration of transportation, supply management, and maintenance.

Engineer Construction Equipment

The Line of Communications Program was undertaken in Vietnam by the 18th and 20th Engineer Brigades. It soon became apparent that there was not sufficient standard military design engineer construction equipment to complete the road construction program within the allotted time frame. Engineer construction equipment is normally associated with long lead times so if the program was to be accomplished by the desired time not only would large quantities of equipment be needed, but more operators and maintenance personnel would be required. Therefore, it was decided to acquire 31 different types of commercial items, totaling 667 pieces at a total acquisition cost of $23,860,000. A plan prepared by U.S. Army Vietnam called for the procurement of the equipment with Military Construction Army funds and included extra major components plus a one-year supply of repair parts. Deliveries covered the period January-September 1969. Maintenance above the operator level and repair parts beyond the one-year overpack quantities were provided by civilian contracting firms.

The M16A1 Rifle

Initially U.S. and allied forces were equipped with either the M14 or M1 rifle. When the decision was made to equip all forces in Southeast Asia with the M16A1 rifle, we were faced with a limited, but growing, production capacity and ever increasing requirements. In country, it was merely a matter of establishing priorities to distribute the rifles as they were received and providing for the turn in of the M 1 and M14 rifles for reissue or retrograde. In the Continental U.S. however, a central point of contact was established in the Department of the Army in December 1967, specifically the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, to monitor and control funding, procurement, modification,

[44]

distribution, and maintenance of this rifle. This office functioned through December 1970.

Electric Generators

The increased usage of electrically powered equipment by the Army in Vietnam resulted in the requirements for electricity far exceeding that required during World War II. During that war, the average consumption per soldier was in kilowatt hour per day. In Vietnam the average consumption was 2 kilowatt hours per day, a four fold increase.

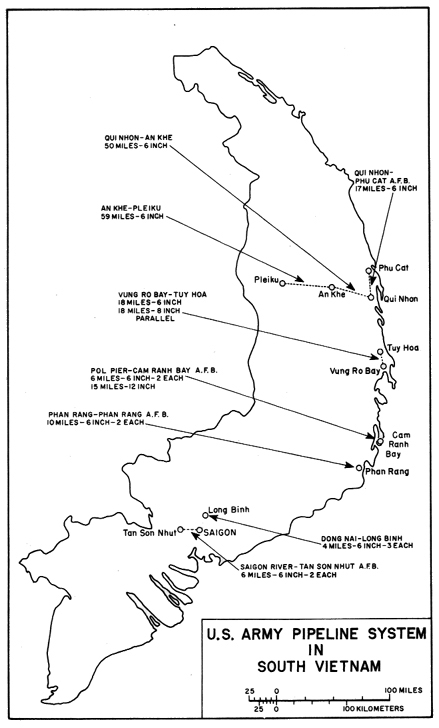

Large capacity generating equipment was needed, because the Vietnamese local power sources were incapable of supplying our requirements. Some of the power requirements were satisfied by converting eleven T-2 petroleum tankers to power barges and by erecting fixed plants throughout Vietnam. The fixed plants were operated by contractors (either the Vinnel Corporation or Pacific Architects and Engineers) since military personnel are not trained in the operation of such commercial type equipment.

Other requirements were met through the diversion of small tactical generators from their normal use. This meant that many small generators were used to perform a task better accomplished with a single large capacity piece of equipment.

With increased requirements came many procurement actions resulting in an extensive number of makes and models in the theater. At the peak of the buildup, there were about 145 makes and models in the 1.5 kilowatt to 100 kilowatt range.

Because of the around-the-clock utilization, age of the assets, lack of parts, lack of an adequate maintenance float, and the numerous makes and models, requirements were generated so rapidly that authorizations documentation could not keep pace, resulting in difficulty in accounting for actual assets on hand. With time and strong management efforts the situation improved. Power requirements were met through additional inputs, a reduction in requirements, and the washing out of some of the non-standard equipment. However, complete standardization will not be possible until the introduction of the Military Standard Family which is programed for fiscal year 1973.

The M107 Self-Propelled Gun Tube

The M107 Self-propelled Gun, mounting the 175-mm M113 gun tube, was introduced into South Vietnam by artillery units arriving in late 1965. This weapon posed significant operational

[45]

readiness problems in early 1966. Due to inadequately trained maintenance personnel and a shortage of manuals, there was a 30 percent deadline rate. The rate of fire of these weapons was consuming tubes on the average of one tube per gun every 45 days. Since this far exceeded the planned consumption rate, the Commanding General, U.S. Army matériel Command initiated a worldwide cross leveling action to provide the U.S. Army Vietnam requirements. At the same time, he advised U.S. Army Vietnam of the results of a test utilizing a titanium dioxide additive, supplied in a cloth sleeve, which had doubled the 175-mm gun tube life expectancy. This increased tube life was expected to ease the critical supply posture in the 175-mm gun tubes. However, in July 1966 a catastrophic failure of a 175-mm gun occurred in U.S. Army Vietnam and the Commanding General, U.S. Army Materiel Command, directed that no tubes, even with the additive, would be fired beyond 400 rounds at equivalent full charge.

The supply situation on gun tubes remained critical and Continental U.S. airlift was employed to satisfy most of the U.S. Army Vietnam requirements of this item through July 1967. In September, gun tube shipment by surface transportation was begun. The U.S. Army Vietnam stockage objective was attained in December 1967 and in January 1968 the U.S. Army Vietnam tube consumption stabilized.

Tropical Combat Uniforms and Combat Boots Under FLAGPOLE

During the period August 1965 to August 1966, the Office of the Secretary of Defense originated a system for reporting items considered essential to the Army Buildup by U.S. Army Vietnam field commanders under the code name FLAGPOLE. This was a technique used by Secretary of Defense McNamara to be kept advised of the status of selected critical items.

Two of the items which came under FLAGPOLE were tropical combat uniforms and tropical combat boots because at the onset of the conflict these items were in short supply. Procurement and distribution of these items was controlled by the joint Materiel Priorities Allocation Board established by the joint Chiefs of Staff who allocated monthly production to the services.

During the period of critical short supply, all Army deliveries of tropical combat uniforms and boots, relatively new items in the supply system, were airlifted from producer to U.S. Army Vietnam without the need for the command to requisition on the Continental U.S. Automatic air shipments continued through May 1967. Pending availability of tropical combat uniforms and boots

[46]

in the Continental U.S., Department of the Army established a policy in September 1965 whereby personnel deployed from the Continental U.S. with four utility uniforms and two pairs of leather combat boots. The tropical combat items were subsequently obtained by the individual in Vietnam. This policy continued until a sustained supply position was reached. Effective 1 July 1967, units deployed were equipped at home station with five combat uniforms and two pairs of combat boots. On 1 August 1967, personnel replacements en route to Vietnam (excluding E-9s, W-4s, and field grade) were issued four tropical combat uniforms and one pair of combat boots at the Continental U.S. Personnel Processing Centers; E-9s, W-4s, and field grade, because of direct call to aerial port, received these items in Vietnam. The distribution of lightweight tentage, lightweight ponchos, collapsible canteens and canteen covers was also controlled by joint Materiel Priorities Allocation Board. Air deliveries were made from contractor source to U.S. Army Vietnam without the need for the command to requisition on the Continental U.S. The "push" method of supply for these items ended in May 1967, at which time the availability was adequate for U.S. Army Vietnam to requisition on the Continental U.S.

Dry Battery Supply and Storage

The supply system provided dry batteries designed with the assumption that adequate refrigerated space would be available to prevent deterioration in the extreme temperatures common to Vietnam. However, there was not enough refrigerated space available in Vietnam to provide the protection for the required stock levels. The combination of the lack of refrigerated storage space, the temperatures in Vietnam, and an overtaxed supply system resulted in a system of expedited battery resupply out of Japan known as Project "Orange Ball." It was initiated in 1968 and involved the use of 20' x 8' x 8' refrigerated containers delivered in frozen condition every ten days to U.S. Army Vietnam depots. Project "Orange Ball" was designed to modify the supply system so that smaller quantities of batteries were provided to the user at more frequent intervals. To provide the batteries faster under Project "Orange Ball," units that required batteries hand-carried requests for a two or three days supply to their Class I supply points. On their next scheduled visit to the supply point, two or three days later, they drew the batteries they had requested on their previous visit along with their rations, and at the same time submitted another request for two to three days supply of dry

[47]

batteries which they would pick up on their next scheduled visit. From this specialized system, a direct delivery system of dry batteries from Continental U.S. To U.S. Army Vietnam was instituted. Exclusive dedicated transportation by refrigerated container vessels (Sea and Land) was utilized. By this method, dry batteries for U.S. Army Vietnam were shipped direct from the Continental U.S. contractor plants to Oakland Army Terminal on a bi-weekly basis. Dry batteries were then shipped by the refrigerated vessels to depot facilities in U.S. Army Vietnam. Upon their arrival in Vietnam, established "Orange Ball" procedures were used.

There were three main phases of the conflict in Vietnam: buildup, sustaining, and phasedown. Each phase required special management techniques.

During the buildup phase, emphasis was placed on getting equipment and supplies into Vietnam without regard for the lack of a sufficient number of logistic units in-country to account for and effectively manage the incoming items. This of course was necessitated by the rapidity of the buildup and the tactical requirement to increase the combat strength in South Vietnam as rapidly as possible. As a result, supplies flowed in ahead of an adequate logistics base, preventing the orderly establishment of management and accounting operations.

The sustaining and drawdown phases can be considered together. During the sustaining phase, there were enough logistics units to start managing the supplies in Vietnam, to identify excesses, to retrograde unnecessary stocks, and to create order out of chaos. What was started during the sustaining phase was not only carried over in the drawdown, but was intensified and added to. Interestingly enough some of the management devices used to support the buildup were useful in the latter two phases and were adopted for worldwide use.

To support the buildup, many intensive management systems were employed. Eight of the most significant are described in the following paragraphs. They are as follows: the HAWK Stovepipe, Red Ball Express, the Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee, Quick Reaction Assistance Teams, ENSURE, Closed Loop Support, Retrograde of Equipment-KEYSTONE, and the Morning Line of Communications Briefings, Vietnam.

[48]

Hawk Stovepipe

The 97th Artillery Group (Air Defense), equipped with the Hawk missile system, was deployed to Vietnam in September 1965. This was the first occasion for the Army to deploy a complex missile system into an active theater, and much attention was given to its support. Since there was no Army Hawk logistic support system in Vietnam at the time of deployment and since this was the only Army using unit, an opportunity existed to establish a logistic system to support this weapon with operational readiness being the paramount consideration (the U.S. Marines had Hawk and a logistic system which was later changed to rely on the Army for parts support) .

The support system developed for the Hawk battalions used a logistic line from the United States supplier directly to the using Hawk organization, thus the name Hawk Stovepipe. The Vietnam end of Stovepipe was the 79th General Support Unit which stocked all repair parts, both common and peculiar, required for support of Hawk. The United States end of the Stovepipe was the Army Missile Command's National Inventory Control Point. All echelons between the inventory control point and the 79th were bypassed. The inventory control point was the single point of control over all requisitions received. Requisitions flowed from a Hawk battery to its battalion direct support platoon, to the 79th, then daily via U.S. air mail to the National Inventory Control Point. Usually within two hours after receipt, the inventory control point took action and materiel release orders were issued. Requisitions for other Continental U.S. National Inventory Control Points of the Army Materiel Command, Defense Supply Agency, or Federal Supply Service (General Services Administration) were sent to the Missile Command National Inventory Control Point for rerouting to the supplying National Inventory Control Point. Follow-up action was taken by the Missile Command National Inventory Control Point on all requisitions, relieving the 79th General Support Unit of this administrative burden. Transportation was coordinated by a Missile Command transportation officer within the terminal areas at Fort Mason and Travis Air Force Base, California. The majority of shipments were flown to the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, located a short distance from the 79th General Support Unit's Hawk support element.

As a result of this system, high priority requisitions for parts were filled within eight days of receipt and lower priority requisitions were filled within 17-18 days of receipt. Another measure of the success of the Stovepipe system in Vietnam was the Hawk

[49]

system's operational readiness rate which averaged 90 percent. This was well above the readiness rate of Hawk units in the rest of the world. The Hawk Stovepipe's success in Vietnam prompted its adaptation to missile systems in other theaters.

Red Ball Express

Red Ball Express was a special supply and transportation procedure established by direction of the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Installations and Logistics) on 1 December 1965. Red Ball Express was designed to be used in lieu of normal procedures exclusively to expedite repair parts to remove equipment from deadline status. Reserved and predictable airlift directly responsive to General William C. Westmoreland was made available for this purpose.

Weekly reports were provided to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, on the not operationally ready-supply rates of specific critical items that he selected for review. The Red Ball Express system, as described below, was highly successful in reducing and maintaining deadline rates to acceptable levels.

A Red Ball Control Office was established in Saigon with the Logistics Control Office, Pacific designated as the focal point in the Continental U.S. for system control. Travis Air Force Base was used as the Aerial Port of Entry for all Red Ball Express shipments. Special Red Ball sections were established at each Continental U.S. supply source.

Red Ball Express requisitions were prepared by the using units and placed on the nearest Direct Support Unit for supply. If the Direct Support Unit could not fill the requirements, the requisition was forwarded to the supporting depot. If the depot could not satisfy the request, it was forwarded to the Red Ball Control Office in Vietnam, where in-country assets were searched for available stocks. If the requisition could not be satisfied in-country, it was then forwarded to the Logistics Control Office, Pacific for forwarding to the appropriate Continental U.S. Supply source. The Logistics Control Office, Pacific also contacted U.S. Army Vietnam for additional information, verification of stock numbers, quantities, or other missing or incorrect information to preclude the requisition from being rejected. Continental U.S. Supply sources furnished the Logistics Control Office, Pacific with shipping information on Red Ball Express requisitions. All Red Ball Express shipments were sent to Aerial Port of Entry, Travis Air Force Base, California, via premium transportation or air parcel post depending on the size and weight of the shipment. At Travis Air Force

[50]

Base, Red Ball Express shipments were segregated according to their intended destination. When Red Ball Express materiel was air lifted, the Logistics Control Office, Pacific was furnished copies of aircraft manifest pages together with the tail numbers of the aircraft and in turn these data were furnished the Red Ball Control Office, Vietnam via telephone or teletype.

The final report submitted as of 31 July 1970 indicated approximately 927,920 net requisitions were processed from inception. Of this total, 98.1 percent or 909,998 requisitions representing 66,985 short tons were airlifted to Vietnam. The Red Ball Express Hi-Pri requisition rate in relation to the Army's worldwide demands placed on Continental U.S. sources averaged 2.2 percent for the period fiscal year 1968 through fiscal year 1970.

In 1968-69, Department of the Army objectives were reoriented toward a streamlined system designed to improve response to the customer. Department of the Army Circular 700-18, published in November 1969, advanced these objectives by providing guidance on an INVENTORY-IN-MOTION principle of non-stop support direct from Continental U.S. To the Direct Support Unit level. The circular tasked Army Materiel Command to position stocks in theater oriented depot complexes and to develop the logistics intelligence to control the system. The circular laid the ground work for the Army's current worldwide Direct Support System. Red Ball program characteristics, to include the integration of supply, transportation, and maintenance activities into a single system, the positive control of requisitions from inception at the Direct Support Unit until matériel is delivered to country and the generation and application of management data were applied in the design of the Direct Support System. Since July 1970, Direct Support System has been changing the image of large overseas depot operations. It is supporting the Army in the field directly from the Continental U.S. wholesale base, bypassing theater depots and break bulk points. The overseas depots have gradually assumed the role of advance storage location for War Reserve, Operational Project Stocks as a safety level.

Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee

It was clear in 1965 that depot stocks of major items and assets coming from production would be inadequate to satisfy the demands of the buildup and other worldwide requirements. If everything were to go to Vietnam (as its priority would have permitted) , the readiness posture of the rest of the Army could have been degraded to an unacceptable degree. For this reason, the

[51]

Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee was established to control the distribution of short-supply end items. This was to insure that the Army's available assets would be allocated in such a way that the Army would realize the maximum benefits.

The committee was chartered under Army Regulation 15-9 which established it as an agency of the Department of the Army staff and gave it sole responsibility for the items under its control. It was chaired by the Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics (Supply and Maintenance) and had as participants members of the Department of the Army staff, U.S. Army Materiel Command, National Inventory Control Points, and major Army commands such as U.S. Army Pacific, U.S. Continental Army Command, and U.S. Army Europe. Participation by major commands was helpful in that the asset situation and distribution options could be understood and appreciated by all concerned at the same time.

Since its founding the concepts and functions of the committee have undergone an evolutionary change. While insuring that the requirements of Vietnam were satisfied, it was at the same time instrumental in restricting and stopping the influx of excess equipment to that theater in 1969. This was possible because of visibility of unit status and authorizations at the Department of the Army level. Other uses of the Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee were to monitor long range distribution plans, to provide data available within Department of the Army for response to quick reaction queries concerning the Army's capability to support alternative organizational concepts or assistance programs, and to override procedures that would normally be correct but that would be unwise for a particular situation.

Quick Reaction Assistance Teams

To provide prompt response to requests for assistance from Vietnam, the Department of the Army directed the Army Materiel Command to form quick reaction assistance teams. By mid February 1966, Army Materiel Command had established a roster of Department of the Army civilian specialists who were prepared to depart from the Continental U.S. on 48 hours notice and remain in the theater up to 90 days to provide the expertise the undersized logistics force lacked. The roster consisted of over 300 personnel in various grade and skill levels within approximately 40 functional areas of supply and maintenance operations. These individ-

[52]

uals were issued passports and visas for Vietnam (required at that time). They also received the necessary medical inoculations, so when their particular skills were required, they were able to provide quick reaction assistance.

ENSURE

The ENSURE project encompassed procedures for Expediting Nonstandard Urgent Requirements for Equipment and was initiated on 3 January 1966. The purpose was to provide a system to satisfy operational requirements for nonstandard or developmental matériel in a responsive manner and bypass the standard developmental and acquisition procedures. matériel items were developed and procured either for evaluation purposes (to determine suitability and acceptability) or for operational requirements. The procedure was applicable to matériel required by either U.S. Army forces or allied forces, or both. The Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development was designated the principal Department of the Army staff member to control the ENSURE project. All ENSURE requests were sent to his staff for initial evaluation. Concurrently these requests were also provided Commanding General U.S. Army Materiel Command, Commanding General U.S. Army Combat Developments Command, and Commander in Chief U.S. Army Pacific for their evaluation as well.

A total of 394 ENSURE projects have been initiated since the beginning of the program in 1966. As of February 1971, 44 of this total were in the process of being evaluated, 159 had been cancelled and 191 were completed. Completion of an ENSURE project is accomplished when the equipment is type classified as either Standard A or Standard B.

Logistic support of an ENSURE item, after type classification, follows the normal support procedures associated with any other standard piece of equipment. During the period an ENSURE item was under evaluation, logistic support was provided by the appropriate National Inventory Control Point using the development and procurement support package developed when the items were approved for acquisition and evaluation.

Closed Loop Support

During December 1966 another special intensive management program was developed to control the flow of serviceable equipment to Vietnam and the retrograde of unserviceable assets to repair facilities. Closed Loop supplements the controls inherent in the

[53]

normal supply and maintenance system. In January 1967, the program was initiated for management of selected Materials Handling Equipment, Communications and Electronics Equipment, the M48A3 Tank, the M113 and M113AI Armored Personnel Carrier and related major assemblies and components.

The objectives of Closed Loop Support were to insure timely response to the needs of operational units, to exert more effective control of critical serviceable and unserviceable assets in the logistics pipeline, to reduce the backlog of unserviceables at all levels, to insure the timely availability of reparable assets at depot maintenance overhaul facilities, and to improve asset control of the flow of controlled items throughout the system. This integrated program provided better asset visibility for the Army matériel managers to plan, program, fund, and operate the Army logistic system more efficiently.

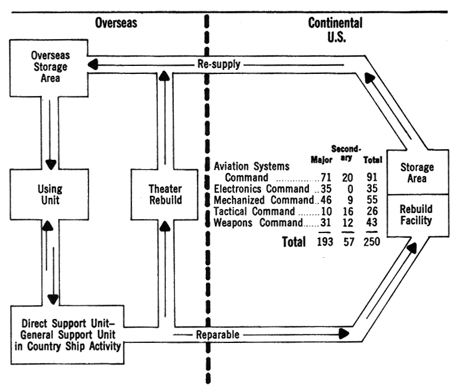

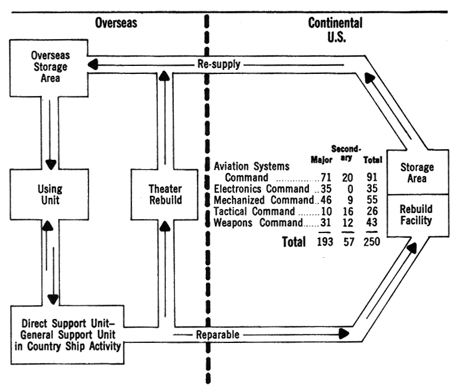

Closed Loop Support is a totally integrated and controlled special management program in which Department of the Army designated major end items of equipment and secondary items are intensively managed through the supply, retrograde, and overhaul process to and from respective commands providing positive control and prescribed levels of logistics readiness.

Fundamental to the Closed Loop Support system is the Closed Loop Support network, an Army-wide functional grouping of controlled activities, supply, maintenance, and transportation elements through which the Closed Loop Support system is operated and controlled. (Chart 3)

The following criteria governed the selection of items nominated for intensive management under the Closed Loop Support system: items whose high unit cost and/or complex nature limits normal logistical support; items essential to a particular mission; items in short supply that impact most severely on operational readiness of a given command; items in a critical worldwide asset position; and items considered critical by a major Army commander. Some of the criteria were the same as those used in selecting an item for Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee control. Indeed many Closed Loop items were controlled by Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee. Therefore, at the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics level, Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee and Closed Loop staff responsibilities were in the same staff element.

Within Department of the Army Distribution and Allocation Committee the new or repaired assets are the "managed" items.

[54]

CHART 3 - CLOSED LOOP SUPPORT NETWORK

Closed Loop differs in that the repairable assets constitute the life blood of the system. Army management, at all levels, gave special attention to predicting and controlling the flow of unserviceable items to and from repair and overhaul facilities. To provide incentives for local commanders to turn in operating equipment scheduled for repair, it was necessary to have a replacement item available for direct exchange. The concept was simple and basic, but smooth operation of the concept in a system as large as the Army's requires more than routine controls.

Once an item was selected as a candidate item, a detailed review process was conducted at a Closed Loop Support Conference. Representation at the Closed Loop Support Conference included representatives from the interested commands and activities, for example Department of the Army, Army Materiel Command, Major Commands, National Inventory Control Points, National Maintenance Points, Project Managers, Defense Supply Agency and others as appropriate. Conferees analyzed the allowances for equipment (Tables of Allowances and modified Tables of Allowances, Special Authorizations, Tables of Organization and Equipment and Modified Tables of Organization and Equipment) ; stock status of

[55]

equipment on hand by condition code previous transaction history; maintenance capability of direct and general support units, in-country depots, in-theater depots, Continental U.S. depots and contractor capability and availability; current repair and overhaul schedules; and procurement delivery schedules. After being approved as a Closed Loop Support item, the item was intensively managed and controlled at all logistic levels.

Closed Loop project officers were appointed at Department of the Army and in each major command, agency, or activity by functional commodity or weapons system. These project officers were the principal points of contact in the network. They performed their Closed Loop Support duties in addition to their other duty assignments.

Each Closed Loop Support item was assigned a project code. This project code was then the trade mark of that particular item providing a ready identifier for that item on all documentation (including transportation and handling), in all communications, and on all packaging and crating.

The following three types of reports were used by the system:

1. A monthly Closed Loop Support summary which was a resumé of programmed versus actual performance. This report was compiled by Army Materiel Command from information received from Logistical Control Offices, supply and maintenance depots, supported commands, and any other activity which may have had an assigned function in carrying out the Closed Loop Support program.

2. Problem Flasher messages which provided warnings of potential deviations from the scheduled movements of serviceable input, retrograde matériel, and matérial to be overhauled. Problem Flashers also described actions being taken to compensate for program deviations, gave the anticipated recovery date, and information as to any assistance required.

3. Real-Time reports were dispatched by priority message by transceiver for each serviceable item shipped from or received by Continental U.S. And overseas air and water terminals. These reports provided notification of lift and receipt data to interested activities. The Closed Loop concept was initiated to provide critical item management for U.S. Army Vietnam. However, from this origin, the system has been expanded to the remainder of the U.S. Army.

Retrograde of Equipment-KEYSTONE

In mid-June 1969, the President of the United States announced the first incremental withdrawal of U.S. Forces from the Republic

[56]

of Vietnam. This initial redeployment withdrawal phase was given the project name KEYSTONE EAGLE.

The initial KEYSTONE increments identified problem areas in the classification and disposition of equipment generated by redeploying units. The standard technical inspection required extensive technical expertise and was time-consuming. Concurrently, the KEYSTONE processing points were experiencing a large backlog of equipment while requests for disposition and/or claimants were processed.

Two management techniques evolved in support of KEYSTONE Operations. The classification of matériel was modified to reflect the level of maintenance required to upgrade the matériel for issue. SCRAM was the acronym used to identify Special Criteria for Retrograde of Materiel. SCRAM 1 matériel can be issued "as-is" or requires minor organizational maintenance. SCRAM 2 matériel requires Direct Support or General Support maintenance prior to issue. SCRAM 3 matériel must be evacuated for depot maintenance. SCRAM 4 is unserviceable or economically unrepairable and is processed to property disposal.

The second technique provided the KEYSTONE processing centers with disposition instructions in anticipation of equipment being turned in. The "predisposition instructions" were prepared based on estimates of quantities of equipment as well as estimates of the condition of equipment to be released by redeploying units. This asset projection was matched against other claimants for the serviceable equipment; unserviceable equipment was reviewed against approved maintenance programs. Generally, available items were used first to satisfy Southeast Asia requirements, then other U.S. Army requirements. The primary considerations in the preparation of these instructions were to preclude the transshipment of equipment, to reduce shipping costs wherever feasible, and to preclude the retrograde of matériel not required elsewhere.

Morning Line of Communications Briefings-Vietnam

Major General Charles W. Eifler, who was the Commander of the 1st Logistical Command in Vietnam from January 1966 to June 1967, developed a system for reviewing the status of stockage for Classes I, III, and V types of supply. The system involved the daily review with his seven Directors and three staff officers along with their senior advisers of the stockage status for these classes of supply. The review utilized charts which covered every Depot, Supply Point, and every Supply Area in support of combat operations in Vietnam. The daily review covered significant data for

[57]

the number of troops supported and established stockage objectives which were compared with the Receipts and Issues for the preceding twenty-four hours. An analysis of the stock balance was made each day and management action was taken on the spot when any area appeared to be in a critical position. It was an extremely effective management tool and there was seldom a day without a significant management action being taken on one of these classes of supply.

Other areas that could be critical were also reviewed at the same morning sessions. Examples are: the number of artillery pieces deadlined with the reasons and actions being taken, and the status of port facilities with particular emphasis given to number of ships awaiting discharge and the number programed for the next thirty days. To put the logistic picture in the proper perspective a detailed review of the tactical situation was conducted every morning.

Project for the Utilization and Redistribution of Matériel

During late 1967, after the Vietnam buildup had been largely completed, excess began to attract serious attention. Secretary of Defense McNamara took unprecedented action and directed that action begin immediately to redistribute excesses prior to the conclusion of the conflict, so as to assure their application against approved military requirements elsewhere in the military supply system. This action was designed to preclude a recurrence of the history of excesses and surpluses following past conflicts. In his memorandum of 24 November 1967, establishing the Project for the Utilization and Redistribution of Materiel, the Secretary of Defense designated the Secretary of the Army as the executive agent for the Department of Defense and further directed that an Army general officer be designated as the Project Coordinator. The Commander-in-Chief, Pacific was directed to establish a special agency to maintain an inventory of excess matériel, supervise redistribution or disposal of such matériel within his area, and report the availability of matériel which could not be utilized in the Pacific area to other Defense activities in accordance with procedures developed by the Project Coordinator.

The Commander in Chief, Pacific established the agency directed under the 2d U.S. Army Logistical Command on Okinawa. The agency was known as the Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency.

Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency initiated operation on 1 April 1968 on a semi-automated basis which continued until 30 June 1968 at which time it was fully automated.

[58]

Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency has undergone some major improvements to increase utilization of the excess matériel. In July 1968, a special off-line teletype screening procedure was developed and implemented in the Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency operation to expedite the screening of bulk-lot items by Continental U.S. inventory managers and supply activities in the Pacific Command in 21 days. This procedure provided rapid disposition instructions to the owning service in order to open up critically needed storage space. In November 1968, the funding policy was revised to permit the transfer of specific categories of service excesses between Pacific Command component commanders on a non-reimbursable basis at field level. In December 1968, a team of merchandising specialists was sent to Okinawa to develop an intensified merchandising program. The task was to produce a catalog on high dollar value items which could be distributed to the Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency customers. The catalog provides visibility, interchangeability and substitute capability. In May 1969, a controlled free issue program was implemented in Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency, whereby matériel designated by Defense Supply Agency and Government Services Administration as not returnable to the Continental U.S. Wholesale level could be issued without charge to the Pacific Command military customers. The free issue program was expanded in July 1969 to include selected expendable and shelf-life items.

In July 1969, Commander in Chief Pacific initiated a study to redesign the Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency operations and Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Installations and Logistics) directed implementation of some of the major concepts included in the Commander in Chief Pacific study, which were designated as Quick Fix improvements. These improvements included increased military service and other Federal agency participation, Closed Loop status reporting, up-grade of the Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency automatic data processing equipment, and a reduced screening time concept. The Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency Quick Fix improvements were implemented on 1 October 1970. These improvements had a significant impact in the Department of Defense excess screening cycle by reducing the screening time from about one year to about 75 days.

During the period 1 April 1968 through January 1972, the Military Services nominated $2.1 billion worth of excess to Pacific Command Utilization and Redistribution Agency for screening.

[59]

Of this $306 million worth was redistributed in the Pacific Area and other overseas commands and $710.3 million worth was returned to the Continental U.S. Wholesale system, resulting in utilization of $1.03 billion, or approximately 48 percent utilization. The balance of this material was declared Department of Defense excess and returned to the owning Services.

Managing the Logistics System

During the buildup and into the Spring of 1967, management emphasis was on getting the supplies to the combat units. The influx of logistics units to Vietnam; the need to establish depots, ports, and organizational structures; and just coping with a rapidly expanding system needing more resources than were available relegated anything not related to the top priority effort to the status of a back burner project. Excesses accumulated, but were not recognized, and requisitions continued to be submitted to Continental U.S. For items that were already in excess in Vietnam.

The nature of operations was such that authorizations did not necessarily represent the needs of units. Units often needed more or different items than were authorized and the requisitioning system honored such requisitions. The Army Authorization Document System was not able to keep up with the needs. Equipment a unit had in excess of its authorization was not reported in its inventory reports (Army Regulation 711-5) .

Frequently documentation on incoming supplies was either lost or illegible upon arrival of the supplies and the contents of containers was unknown. Unqualified supply personnel set aside these containers to be identified later, which frequently extended beyond the rotation date of the individual who had knowledge of the circumstances.

Failures of the supply system to locate, identify, and provide a required item undoubtedly degraded supply discipline at the using unit level which in turn made a substantial contribution to further breakdown in control and to increasing excesses. Rather than using normal follow-up procedures, it was common for the requesting unit to re-requisition the needed items one or more times, thereby bringing unneeded items into country as well as creating inflated demand data at the supporting units and depots.

In the spring of 1967, concern about the numbers of high priority requisitions being received from Vietnam caused a number of National Inventory Control Points, U.S. Army Pacific Headquarters, and other commands in the requisitioning channel to challenge requisitions. Later the program was formalized under the name

[60]

Project CHALLENGE, which required unit commanders to verify the priority of the requirement. Project CHALLENGE reduced premium transportation and handling costs and started to reinstate some degree of control on the requisitioning process.

In addition to the excesses created by the Push Packages arriving in-country prior to the arrival of adequate logistics units, the deterioration of identification markings on packages added even more excesses as the unidentified items on hand were re-requisitioned.

The personnel assigned as warehousemen were generally untrained and inexperienced in supply operations which added to the confusion. To attempt to rectify this lack of experience and training, the Department of the Army instituted Project COUNTER.

Early in 1967 a group of supply assistance personnel from U.S. Army Materiel Command organizations went to Vietnam on temporary duty, under the code name Project COUNTER. These people provided formal instruction in supply procedures and assisted in-county personnel in performing location surveys, conducting inventories, identifying and classifying materiel, reviewing and improving prescribed load lists and authorized stockage lists, and generally assisted in supply management activities. In all, a total of four Project COUNTER teams were provided during 1967-1968 and proved extremely helpful in upgrading the technical competence of supply personnel in Vietnam.

In order to direct attention and effort to the many tasks that had to be performed once there was a satisfactory logistic base in Vietnam, the Commanding General of the 1st Logistical Command established an extensive command and control program for logistics management in 1968. The program was formalized into a number of objectives, performance statements, and progress reports, which were incorporated in a command publication referred to as the Pink Book. This was given wide distribution within the 1st Logistical Command and tied together short and long range projects in all logistics areas to increase efficiency, to bring stock levels down, and to identify and reduce excesses.

Early in 1969, during a meeting at Phu Bai including General Abrams, Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, the Commanding General of the 1st Logistical Command and others, General Abrams used the term Logistics Offensive to describe what was required of the Army logistics system in Vietnam. While General Abrams meant it as a compliment for the progressive improvement being made in all areas of logistics, in reality he had issued a resounding challenge to all professional Army logisticians to in-

[61]

stitute a series of actions with follow-up attention, similar to those employed by tactical commanders in launching offensive operations.

Soon after this, the 1st Logistical Command's Pink Book became known as the Logistics Offensive Program. This program was adopted by Department of Army for Army-wide application in September 1969. By 31 March 1971 this program had grown to include over 130 different projects. The following list contains some of the projects contained in the Logistics Offensive Program.

Sample Projects of the Logistics Offensive Program

1. Inventory in Motion

2. VERIFY

3. STOP/SEE

4. CONDITION

5. CLEAN

6. Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedures (VARP)

7. SEE MOVE

8. KEYSTONE

The concept of Inventory in Motion was first applied to ammunition and is discussed in some detail in the ammunition chapter. As applied across the board, inventory in motion was a supply management program that had as its goal integrating supply and transportation to reduce the requirement for stock levels in Vietnam and other storage areas.

Integrated planning and control of the movement of supplies resulted in responsive resupply and smaller local inventories. Having fewer supplies on hand meant reduced care and preservation efforts, smaller storage areas to protect, and easier inventory management. Basically stocks in transit or in the pipeline were considered as being part of the inventory.

The use of the inventory in motion concept for ammunition and bulk petroleum was facilitated by the relatively small number of different items and predictable consumption rates. Likewise, consumption of subsistence was relatively stable, being pretty much in proportion to troop strength. The effectiveness of applying inventory in motion procedures to other supplies such as repair parts, clothing and individual equipment, administrative and housekeeping supplies and equipment, principal items, and packaged petroleum products was more difficult because of the large number of items and varying demand rates. One of the major problems was the lack of data announcing that truck convoys, airplanes, or vessels were scheduled to arrive on given dates. Consequently, advance

[62]

planning at storage activities was limited and matériel actually in transit could not be considered as assets.

It became apparent that an interface between supply and transportation data was necessary to achieve the desired asset visability of in-transit matériel. A conference was held in September 1969 with representatives of U.S. Army Pacific, U.S. Army Vietnam, 1st Logistical Command, and the U.S. Army Logistics Control Office Pacific which resulted in creating a Logistics Intelligence File. Through the Logistics Intelligence File, U.S. Army Vietnam and the Central Financial Management Agency, Ft. Shafter, Hawaii, were able to have daily updated information on each open requisition. This gave U.S. Army Vietnam the capability to determine where any requisition was at any time, e.g., in process at the Continental U.S. National Inventory Control Point depot, in-transit to the terminal, or in the terminal awaiting lift, as well as the lift data (such as transportation control number, carrier, and estimated time of arrival). Through use of the Logistics Intelligence File, the concept of inventory in motion has been applied to most commodities in Vietnam.

Another management program, Project VERIFY, was established in Vietnam to study the management procedures and statistical data used by the 1st Logistical Command to describe and evaluate its logistic efforts. The aim of Project VERIFY was to produce standardized management procedures, statistical terms, and usable standards that could be expressed as management objectives.

The project concerned itself with the movement of supply items through the depots. It also was concerned with the flow of paperwork pertaining to these supplies-noting the paths of the various copies in order to determine the control measures used. Data were sought to determine the time frames involved in the various processes. These data were analyzed and corrective actions were taken when deficiencies or inefficiencies were found. This helped to implement other projects designed to speed up the movement of supplies to the requesting units.

During 1968 it was becoming apparent that items were being requisitioned on a routine basis that were not actually needed in Vietnam. What the situation needed was some degree of personal attention to prevent the shipment of these items. In June 1968, Project STOP was initiated in U.S. Army Vietnam for the purpose of preventing shipping of supply items from Continental U.S. that were not needed in Vietnam. All possible actions were taken from canceling requisitions not yet filled to stopping shipments up to the point where items were loaded on board ship. In addition, related

[63]

procurements were terminated, stretched out, or diverted to other uses. Stops on requisitions started with the 1st Logistical Command's submission of requests for cancellation of specific items by Federal Stock Numbers. Items stopped were either stocked in Vietnam in quantities excess to the requirements there, or in quantities exceeding the depot system's capacity to handle and store.

In September 1968, Project SEE began with teams established at each major post in U.S. Army Vietnam to devote full time to physically examining (seeing) bulk items in storage at depots, on the piers, and being unloaded from ships. These teams initiated immediate action to determine whether the items aboard ships should continue to be unloaded, or whether they should be diverted elsewhere (in country or out of country). When an item not desired was located, action was initiated to have the appropriate Federal Stock Number broadcast to all supply agencies involved including Army Materiel Command, Defense Supply Agency, and 2d Logistical Command in Okinawa, so that action could be taken throughout the system to stop movement of this item to Vietnam.

In late September 1968 Project STOP and Project SEE were merged into one project which was given the code name of Project STOP/SEE. Under this concept 1st Logistical Command designated items on a STOP/SEE listing by Federal Stock Number and nomenclature which were in long supply, items deleted from the theater authorized stockage list, or luxury and convenience items. When an item appeared on one of these listings, 1st Logistical Command suspended requisitioning by blocking the computers in country and sending copies of these listings to Continental U.S. Inventory Managers. These Managers then took steps to locate and cancel all open requisitions for these items and to frustrate shipments through STOP procedures.

Project STOP/SEE EXPANDED was a further extension of Project STOP /SEE and was initiated 19 November 1968. The Commanding General U.S. Army Vietnam, in accordance with Project STOP procedures, requested blocking action by Federal Supply Class with Federal Stock Number exceptions. Under this program, the majority of Federal Stock Numbers within a Federal Supply Class were blocked at the Defense Automatic Addressing System Office and all low priority requisitions (IPD 09-20) for Vietnam were canceled and the shipments were frustrated. High priority requisitions (IPD 01-08) continued to be honored. The U.S. Army Inventory Control Center Vietnam (formerly the 14th Inventory Control Center) then provided a standardized list of Federal Stock Numbers, by Federal Supply Class in card deck format, to the Logistics Control Office,

[64]

Pacific for use in completing Project STOP actions. By the end of February 1971, $644 million of requisitions had been canceled through the use of STOP/SEE techniques.

Project CONDITION was first implemented in the 1st Logistical Command in February 1969. It was implemented because of conditions found to exist when Project COUNT I (reliability of the location system and inventory) and Project COUNT II (100% cyclic inventory) were conducted during the period September 1968 to January 1969. The intent of Project CONDITION was to purify condition data of matériel assets at each depot. It consisted of two basic phases. Phase I was the separation of all stock counted into two categories; first, that stock which was obviously condition A, and second, all other stock which was designated as Code J. Phase II consisted of the condition coding of all incoming depot stocks as either Code A or K. Code K identified all receipts which were obviously not Code A. Quality control technicians inspected and determined the requirements and recommended priorities for care and preservation.

Project CONDITION was extended to Army Materiel Command and other major commands as an integral part of the Logistics Offensive. The objectives were to provide visibility of the actual condition of the inventory worldwide (not in the hands of troops) and to identify and monitor progress on that portion which required care and preservation.

Project CLEAN was established as an integral part of the inventory-in-motion concept to eliminate excess supplies from the Army supply system by determining what supplies were on hand in the field but were no longer required for mission accomplishment, and then to redistribute them to where they were required, retrograde them to maintenance activities, or dispose of them through disposal channels. During fiscal year 1970 and 1971, supplies valued at almost $1.5 billion were eliminated from oversea stocks. In these years, U.S. Army Vietnam alone retrograded over 671,000 short tons of supplies. The authorized stockage list for Vietnam was reduced from a high of 297,000 different items in July 1967 to 74,900 items in March 1971, without any loss of the high quality of support provided to the combat forces.

The Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedures was a program developed in December 1969 to cope with the problem of excesses. A bit of background data reveals that during the buildup and sustaining phases, U.S. Army Vietnam was given first priority for the fill of all major item requisitions. U.S. Army Vietnam requisitions were processed and filled with little regard as to whether formal

[65]

authorization existed. In general, U.S. Army Vietnam requirements were not questioned and requisitions on the wholesale supply system were accepted at face value. This policy was necessary because formal authorization documents could not keep pace with the rapidly changing situation. As a result of this policy, U.S. Army Vietnam developed excess positions for many items. While some of these excesses were real, others were only apparent in that the items on hand were actually required for mission performance, but the need for them had never been recognized in an authorization document. Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedures was intended to establish control over excess assets in the hands of U.S. Army Vietnam units, obtain visibility over the actual requirement situation in U.S. Army Vietnam, and reconcile differences between U.S. Army Vietnam recorded quantities and National Inventory Control Point shipped quantities.

Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedures was unique and constituted a departure from conventional asset control and accounting procedures. Under Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedures, units reported to U.S. Army Vietnam those assets on hand which were in excess of written authority; however, there was no penalty for reporting these excesses. Reporting units were allowed to retain them on loan provided they were required for mission accomplishment. U.S. Army Vietnam reviewed the loans every 180 days as a minimum. Assets on loan to units were accounted for through the depot reporting system (Army Regulation 711-80) ) rather than the unit reporting system (Army Regulation 711-5) . Assets within unit tabular authority continued to be reported through the regular unit reporting system. As of 31 December 1970, approximately $160 million (at budget costs) of previously unreported assets had been accounted for under Vietnam Asset Reconciliation Procedure.

Project SEE/MOVE was begun in July 1969, and sent to U.S. Army Pacific to assist the commands in understanding existing disposition instructions; to provide on-the-spot disposition; and to effect the necessary communication between the sub-commands, Department of the Army, and the appropriate Continental U.S. agencies to obtain rapid disposition instructions (note the relationship with CLEAN) . Later the teams turned their efforts to rendering management assistance to U.S. Army Pacific in such areas as interpretation of Department of the Army, Army Materiel Command, and Defense Supply Agency regulations, policies and/or disposition priorities and instructions and effecting communication and co-ordination with U.S. Army Pacific, Department of the Army and/or other appropriate Continental U.S. Agencies Also, they pro-

[66]

vided U.S. Army Pacific with guidance and on-the-spot disposition instructions for categories of excess matériel not otherwise covered by instructions.

The teams were headed by a representative from Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics with members provided by Defense Supply Agency, U.S. Army Pacific, and U.S. Army Materiel Command. In-country U.S. Army Materiel Command technical assistance personnel were also utilized. Rotation of personnel was at the discretion of the agency concerned. The teams operated under the overall direction of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics and under the control of U.S. Army Pacific. They were deployed to Vietnam and Okinawa in February 1970 and terminated their operations on 15 June 1970. During this period, one team was also sent to Europe.

KEYSTONE was the name given to the program for the withdrawal of the U.S. Forces from South Vietnam. In mid-June 1969, the President of the United States announced the first incremental withdrawal of U.S. Forces. This initial redeployment phase was given the project name KEYSTONE EAGLE.

KEYSTONE EAGLE began on 19 June 1969, and was initially planned as a unit redeployment, with 9th Infantry Division (less one brigade and provisional supporting elements) scheduled to redeploy to Hawaii to reconstitute the Pacific Command reserve. The redeployment was scheduled to be completed on 27 August 1969 to meet the Presidential commitment of having the initial troop withdrawal of 25,000 personnel completed by 1 September 1969. Department of the Army published a Letter of Instruction for the redeployment of United States Army Forces from South Vietnam on 21 June 1969, providing general logistics and personnel policies governing the redeployment. The redeploying units were authorized to redeploy with all Modified Tables of Organization and Equipment equipment, less selected U.S. Army Vietnam designated "critical" items (such as radars and M16 rifles), which were to be retained in-country to satisfy existing shortages within U.S. Army Vietnam units.

The 1st Logistical Command was tasked by Lieutenant General Frank T. Mildren, Deputy Commanding General, U.S. Army Vietnam to provide assistance to the Commanding General 9th Infantry Division and the mission was assigned to the Saigon Support Command. This mission was ultimately expanded to include the provision of complete logistics support of the division during the final 30 days of the redeployment phase. This entire support operation was unique in that it represented the first time in U.S. Army history a unit, actively engaged in combat, was disengaged

[67]

from its mission, withdrawn to a base camp and required to prepare itself for redeployment. The logistic support of this unit redeployment was extremely complex because of the need to continue to support other units still engaged in combat operations while simultaneously inspecting, preparing, packing and shipping the redeploying unit's Table of Organization and Equipment equipment.

The problem was compounded by the fact that the majority of the personnel turning in the division's equipment were not redeploying with their parent unit, but would be reassigned in-country for completion of their twelve month tour. This personnel policy alone taxed the command and control element to the maximum.

Finally, the complexity of this initial redeployment was further compounded by the lack of procedures and matériel to process Table of Organization and Equipment equipment for overseas redeployment to meet the strict U.S. Public Health Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture sanitation and entomological requirements. To assist U.S. Army Vietnam in overcoming these problems, the Commanding General U.S. Army Materiel Command assembled a team of forty civilian personnel and deployed them to South Vietnam in early 1969. Additionally, a Composite Service Maintenance Company (604th Composite Service Company) and a Transportation Detachment (402d Transportation Corps Detachment) were organized in the Continental U.S. and deployed to South Vietnam to assist in unit redeployment. The 604th Composite Service Company was specifically organized to assist in inspection, packaging and preparing equipment for redeployment and the Transportation Detachment was organized to assist with required documentation.