- Chapter IV:

-

- Combined Arms Operations

-

- Armored units fighting in Vietnam by early 1967 included one armored cavalry

regiment, six mechanized infantry battalions, four armored cavalry squadrons,

two tank battalions, an air cavalry squadron, and five separate ground cavalry

troops. By this time it was apparent that armored units of all types were

proving far more useful in combat than had previously been thought possible.

General Johnson, Army Chief of Staff, after discussions of the use of armor

with General Westmoreland in the summer of 1966, directed the Army staff to

determine whether a pattern of armored operations involving both tanks and

armored personnel carriers had begun to emerge in Vietnam. The resulting staff

study recommended an analysis by the U.S. Army Combat Developments Command

for the purpose of suggesting modifications in unit organization, equipment,

training, and deployment.

-

- The MACOV Study

-

- In August 1966 General Johnson approved plans for a study titled Mechanized

and Armor Combat Operations in Vietnam (MACOV) under the direction of Major

General Arthur L. West, Jr. Between January and March 1967 a group of over

100 American Army officers and civilian analysts examined the combat record

of armored and mechanized forces in Vietnam, gathering and studying information

gleaned from the battlefield. The group evaluated over 18,000 questionnaires,

2,000 reports, and 83 accounts of combat in which battalions and larger units

had participated. Its report did not subscribe to the opinion that Vietnamese

jungles and swamps would swallow up armored vehicles, but concluded that habitual

use of armored vehicles against insurgents in jungles and swamps necessitated

some changes in armor tactics. The group found that extensive use had been

made of the armored personnel carrier M113, modified with weapons and gunshields

to become a tanklike fighting vehicle that was known as the ACAV-armored cavalry

assault vehicle. The study group also found that more often than not U.S.

mechanized infantry fought mounted, employing armored personnel carriers as

assault vehicles to close with and destroy the enemy, and that mounted troops

generally suffered fewer and less serious casualties

- [84]

- than foot soldiers. Contrary to established doctrine, armored units in Vietnam

were being used to maintain pressure against the enemy in conjunction with

envelopment by airmobile infantry. Moreover, tanks and APC's frequently preceded

rather than followed dismounted infantry through the jungle, where they broke

trail, destroyed antipersonnel mines, and disrupted enemy defenses. These

findings revealed that some departures from armor doctrine had been taking

place.

-

- The study group noted several of the special advantages armor possessed

in area warfare, described enemy tactics against armor, and listed types of

armor missions. The group concluded that while tank and mechanized infantry

units were playing a significant role in Vietnam, cavalry units, both ground

and air, were essential elements to the important business of finding, pursuing,

and destroying the enemy. Among its important recommended changes for armored

and mechanized units was that organization be standardized for future armored

forces being sent to Vietnam. This recommendation followed the discovery that,

because of extensive and undisciplined modification of tables of organization

and equipment, no two armored units in Vietnam were organized alike. Believing

it impossible for the Department of the Army to support such a diverse force

structure, the study group recommended that the Army strictly enforce conformity

with modified standard tables of organization and equipment of units going

to Vietnam.

-

- Major findings of the study were described in a training manual, a training

film, and an air cavalry text; all were given worldwide Army distribution.

The air cavalry training text in particular was used for several years by

air cavalry units and provided a much needed reference work to explain the

air cavalry mission to ground commanders unfamiliar with the concept. It was

also useful in training troops scheduled to deploy with air cavalry units.

-

- The training manual's coverage was very broad, and when used correctly the

manual was a "how to" book for armored units in Vietnam. Considering

that most of the information bad never been published in one book before,

the manual was a landmark. General Westmoreland wrote the foreward and later

commented that the

- study had prompted him to ask for more armored and mechanized units in troop

requests. The text discussed impassable terrain and maps showed the areas

that could be traversed in the wet and dry seasons. (See Maps 2 and 3.)

In addition, it described the enemy and the frustrating nature of area warfare.

Various battle formations and procedures such as herringbone, thunder run,

and roadrunner were described in detail. The manual also discussed the

- [85]

- cloverleaf, a maneuver particularly suited to armored units, mounted or

dismounted, when they were making a rapid search of a large area.

-

- The impact of the study was something less than many hoped for. The findings

were not surprising to amored troops who had served in Vietnam but were regarded

with a jaundiced eye by others who had not served there. Some data collectors

believed that they were called upon to justify the existence of armor units

already in Vietnam or scheduled to go there, but most members of the study

group were able to put their task into perspective, and none expressed the

justification for the study so well as one who said, "Although I did

not doubt the value of armor in Vietnam, I was, myself, unable to recommend

how much, of what type, and where it could be deployed. It would take a study

like MACOV to provide a basis for these recommendations."

-

- The bulk and security classification of the report prevented its widespread

dissemination. In seven thick volumes, the official study was classified secret

and was supported by six classified data supplements nearly as long as the

report itself. Although its volume and classification were necessary, potential

readers were overwhelmed. Only 300 copies were printed, and few remain in

existence today. The publication of the unclassified training manual and film

was an effort by the study group to gain wider circulation for the information.

-

- At the U.S. Army Armor School and the Combat Developments Command Armor

Agency at Fort Knox, changes in troop and equipment tables were enthusiastically

endorsed, but doctrinal changes were rejected. While the report was clearly

intended only to supplement worldwide armor doctrine, both the agency and

the school argued that the new concepts were not applicable to armor combat

in other parts of the world. Apparently those engaged in formulating doctrine

were less concerned with the study group's conclusions, which were based on

several years of combat experience in Vietnam, than they were with hypothetical

situations in other parts of the world.

-

- The training establishment under the Continental Army Command (CONARC) was

unwilling to accept the study group's observations on the unprecedented role

of M113's as assault vehicles in Vietnam. The command noted that the term

"tanklike" was misleading and that adopting as doctrine the employment

of mounted infantry in a cavalry role was neither feasible nor desirable.

Justification for its position seemed to be couched in contradictory terms.

While the command agreed that more Vietnam-

- [86]

-

HERRINGBONE FORMATION ASSUMED BY 3d SQUADRON, 11TH ARMORED

CAVALRY, DURING OPERATION CEDAR FALLS, This formation gave vehicles best

all-round firepower when they were ambushed in a restricted area.

-

- oriented training and doctrine were needed by deploying units, it refused

to heed those findings of the study that were most attuned to the actual combat

situation in Vietnam. The Continental Army Command decided to leave the matter

to the interpretation of local commanders, although these were the same commanders

who had told the study group that a revision of doctrine was needed to reflect

actual combat experience in Vietnam.

-

- The command also rejected the report's recommendation that the psychological

effect of armored and mechanized units upon the enemy be exploited, stating

that any further study of this matter would probably be superfluous. The implication

was that the psychological advantage was not that great in the first place.

"The Vietnamese people," stated the Continental Army Command, "know

too well of the French Armored Mechanized Units' defeat at the hands of the

Viet Minh and the destruction that can be inflicted on a tracked vehicle by

one Viet Cong with a small amount

- [87]

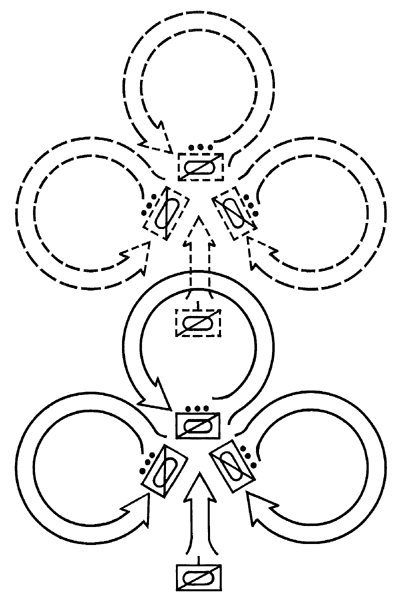

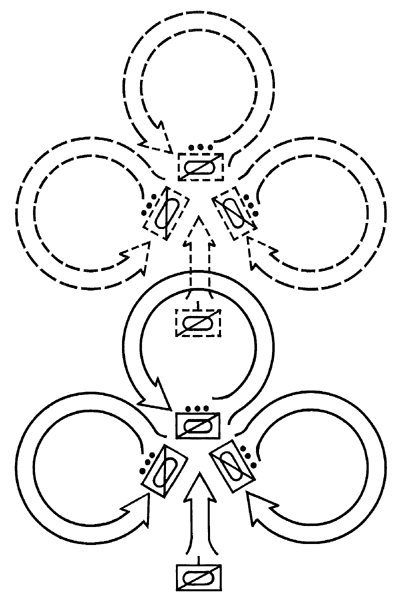

- Diagram 6. Cloverleaf search technique used by armored cavalry troops.

- [88]

- of properly placed demolition material." To some elements within the

command, the shock effect of armor, whether concrete or psychological, no

longer existed, at least not in the case of the Viet Cong or the North Vietnamese

Army.

-

- The Army's equipment developer, the Army Material Command, and the doctrine

agency, the Combat Developments Command, both commented on the report. The

Army Material Command endorsed the majority of the study group's equipment

recommendations but out of necessity qualified the approval with cost and

time factors; it frequently noted feasibility but implied impracticality.

The Combat Developments Command concluded that, with few exceptions, the recommendations

should be carried out for Vietnam, and that certain of them were applicable

to the Army worldwide.

-

- The Combat Developments Command forwarded to the Department of the Army

a strong endorsement of the study group's suggestion that increased emphasis

be placed on the use of armored forces in warfare such as that in Vietnam.

While the Army staff approved many specific recommendations, it did not agree

that increased use of armored units in Vietnam was either necessary or desirable.

In spite of the study group's observations on the usefulness of the M113 as

an armored assault vehicle, the Army staff considered the results of such

employment could only lead to a pyrrhic victory at best: "To modify and

employ this means of transportation as an armored assault vehicle," it

noted, "against an enemy who is daily improving the lethality and effectiveness

of his armament not only decreases the capabilities for which the vehicle

was originally designed, but can result in unnecessary friendly casualties."

This position was totally inconsistent with the real world situation in 1967

in which U.S. and South Vietnamese armored forces were habitually and effectively

employing their APC's and ACAV's as assault vehicles with great, success.

-

- One other circumstance worked against widespread acceptance of the recommendations:

As the study group was preparing to leave for Vietnam in November 1966, Defense

Secretary McNamara imposed an absolute troop ceiling on U.S. forces in Vietnam.

This arbitrary ceiling was well below the total number already in the proposed

troop program of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the United

States Army, Vietnam. In other words, if more armored forces were wanted,

other units had to be given up in order to get them. The situation was complicated

by the fact that recommendations of an earlier study, Army Combat Operations

in Vietnam, completed in 1966, had not yet been acted

- [89]

- upon. The earlier recommendations dealt with infantry problems in Vietnam

in the same detail as the armor study dealt with armor problems; they also

required trade-offs, most of which had not yet been decided upon.

-

- The armor study group applied itself to this problem in a straightforward

way by incorporating the infantry study recommendations and summing up the

cumulative effect of both studies. The group then selected some 4,000 troop

spaces in the proposed force for the US. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam,

that could be traded to carry out the combined recommendations of both studies.

Since the spaces came largely from combat support troops, the logistics and

administrative community vehemently denounced the trade-off, thereby heightening

the opposition to the study group's recommendations.

-

- The armor study raised again all the historic arguments for and against

the use of armored forces in Vietnam. It provided a documented basis for discussion

and, in fact, influenced the training and employment of many armored units.

The Department of the Army subsequently approved organizational and equipment

changes incorporating some of the recommendations. The armored cavalry assault

vehicle, for example, is in the Army today, and fighting mounted from armored

vehicles is an accepted practice. Vietnam related training at the Armor School

was increased from two to twenty hours in mid-1967, although academic department

heads expressed concern that the Army would overemphasize Vietnam at the expense

of conventional armor employment. This attitude was in striking contrast to

that of junior officers and students who knew they were destined for duty

in Vietnam.

-

- Armored units scheduled for Vietnam used the armor study group's training

manual as a guide, but copies were difficult to obtain; many armor officers

never saw it. Only a few years later, units and service schools were hard

put to find the copies they had received.1

Perhaps the most effective dissemination of the study findings came through

the efforts of the group members, some of whom wrote service school lesson

plans, contributed articles to periodicals, and made changes in units in which

they served. All in all, the armor study accelerated changes in the theory

of using armored forces that would be tested and validated by the battles

of the Tet offensive of 1968.

- [90]

- Cedar Falls-Junction City

-

- Early combat operations in 1967 that were observed, recorded, j and analyzed

by General West's study group reflected a definite change in strategy for

American and other free world forces in Vietnam. Until late 1966 General Westmoreland

had employed "fire brigade tactics," reacting to enemy initiatives

with his limited I troop resources. By 1967 the buildup of U. S. forces permitted

him some flexibility, and increases in tactical mobility improved the I effectiveness

of the reaction forces. Thus, in 1967 the mission of American and other free

world units changed to one of offensive action against the main force enemy

units. South Vietnamese forces were to be employed primarily in pacification.

The initiative was passing to the free world forces.

-

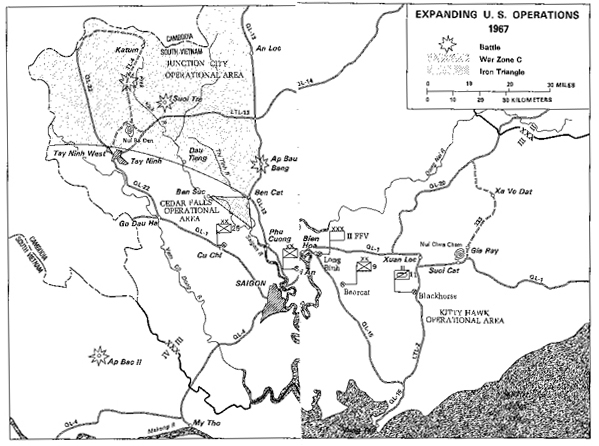

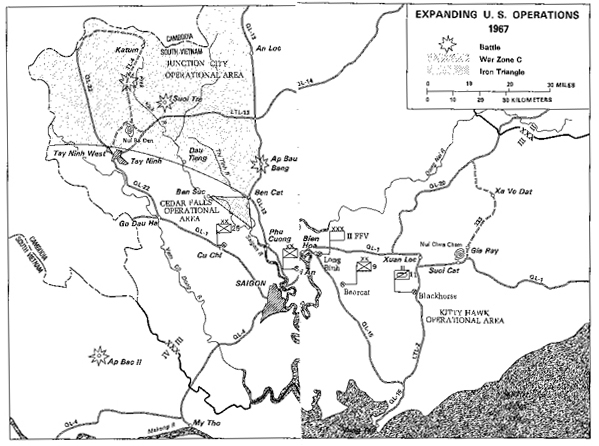

- In the III Corps Tactical Zone the first deliberately planned multidivision

operation, CEDAR FALLS, was begun by II Field Force, Vietnam. The target was

an extensive enemy base and logistical center that because of its geographical

shape and strong defense was known as the Iron Triangle. (Map 8) This

heavily jungled area, twenty-five kilometers north of Saigon, was an important

center for the launching of enemy guerrilla and terrorist operations; it was

frequently referred to as "a dagger pointed at Saigon." The plan

was to seal the area, split it in half, thoroughly search it, and destroy

all base camps and enemy forces.

-

- The Iron Triangle was sealed by U.S. armored and airmobile units. The 2d

Battalion, 22d Infantry (Mechanized) ; 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized)

; 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, and Troop B, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, established

blocking positions west of the Saigon River; the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

E Troop, 17th Cavalry, and Company D, 16th Armor, were employed east of the

Thi Tinh River. Having moved to an assembly area the day before, the 11th

Armored Cavalry, less its 1st Squadron, attacked west from Ben Cat on 9 January

to divide the area in two. Throughout the operation, units combed the Iron

Triangle, uncovering base camps, food, equipment, and ammunition. Fighting

was light and generally limited to scattered encounters with platoon-size

or smaller groups. The value of CEDAR FALLS does not lie in the number of

enemy casualties it produced but in the 500,000 pages of enemy documents it

captured. These exposed the command structure and battle plans of the entire

Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army hierarchy. General Seaman described the

operation as the largest intelligence breakthrough in the war.

-

- Tracked vehicles, which had little difficulty in traversing the terrain,

were assisted in the search by bulldozers. A task force of

- [91]

- MAP 8

- [92-93]

-

M113'S AND M4SA3 TANKS DEPLOY BETWEEN JUNGLE AND RUBBER

PLANTATION IN OPERATION CEDAR FALLS

-

- fifty-four bulldozers with four Rome plows and some tanks with dozer blades

cleared more than nine square miles of jungle, and frequently led armored

columns. In an interesting innovation, the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, used

tank-mounted searchlights to detect Viet Cong night movements along the Saigon

River. Several successful night ambushes were conducted by directing tank

fire against the enemy river traffic.

-

- The wisdom of the 1966 decision to increase the number of mechanized infantry

battalions from two to six was attested to by Brigadier General Richard T.

Knowles, Commanding General, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, in a statement

concerning the role of mechanized infantry in CEDAR FALLS.

-

- Mechanized infantry has proven to be highly successful in search and destroy

operations. With their capability for rapid reaction and firepower, a mechanical

battalion can effectively control twice as much terrain as an infantry battalion.

Rapid penetrations into VC areas to secure Us for airmobile units provide

an added security measure for aircraft as well as personnel when introducing

units into the combat zone. The constant movement of mechanized units back

and forth through an area keeps the VC moving and creates targets for friendly

ambushes, artillery and air.

- [94]

- The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment's success in CEDAR FALLS clearly confirmed

the soundness of the unit's organization. The regimental commander, Colonel

William W. Cobb, reported that the first rapid maneuver into the area and

its accomplishment of search and destroy, screening, blocking, and security

missions demonstrated the flexibility of his unit. He further stated:

-

- The search and destroy portion of Operation CEDAR FALLS was the final combat

test of the modified TOE designed to tailor the regiment's organization to

the requirements of the counterinsurgency operations in Vietnam. The search

and destroy operations, plus the allied saturation and sniper patrols, and

tunnel search operations proved the validity of the MTOE. There proved to

be sufficient personnel in the basic maneuver element-the Armored Cavalry

Platoon-to allow for required dismounted tunnel and patrolling operations

while maintaining sufficient crew members on the ACAV's to maintain the platoon's

mounted combat capabilities.

-

- When Operation CEDAR FALLS ended on 25 January 1967, armored forces of II

Field Force, Vietnam, were committed to Operation JUNCTION CITY, the largest

operation of the war to that date. JUNCTION CITY was designed to disrupt the

Viet Cong Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), destroy Viet Cong and

North Vietnamese forces, and clear the War Zone C base areas in northern Tay

Ninh Province, eighty-five kilometers northwest of Saigon. During the three-phase

operation, armored units served in road security and search and clear operations

and acted as convoy escorts and reaction forces.

-

- Phase I, 22 February-17 March, consisted of establishing a horseshoe blocking

position in northwestern War Zone C, then attacking into the open end of the

horseshoe toward the U end of the position. From Fire Support Base I at 0600

on 22 February, a 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, task force began a twenty-kilometer

move north on Provincial Route 4; its mission was to reinforce quickly the

airborne and airmobile assault elements at the north end of the horseshoe.

To send the cavalry along an uncleared route was a calculated risk, prompted

by the hope that the enemy would not employ mines on one of his few partially

paved supply routes. The gamble worked. The 1st Squadron raced unimpeded to

reinforcing positions south of Katum, and the landings went without incident.

As the cavalry moved north, the 2d Battalion, 2d Infantry (Mechanized), followed

with artillery and engineering units to establish Fire Support Bases II and

III.

-

- At dawn on 23 February, the 2d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, and the

11th Armored Cavalry Regiment began sweeping

- [95]

- north between the sides of the horseshoe. There was scattered fighting as

the armored units found base camps, hospitals, bunker systems, and small groups

of Viet Cong. Mines and booby traps slowed the attack, and in the center of

the horseshoe dense jungle made movement difficult. After reaching the northern

limit of advance, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment pivoted and swept west

with the other forces. Sporadic fighting continued.

-

- For armored units, JUNCTION CITY was a task force operation. Combined arms

operations at battalion and squadron level were normal, and mobility was stressed.

Armored task forces with attached elements of infantry, artillery, tank, and

cavalry roamed through the operational area. Infantry rode on the tracked

vehicles and went into action as tank-infantry teams.

-

- Although enemy resistance gradually stiffened throughout the area, the armored

task forces finally drew out the elusive Viet Cong on the periphery of the

operation. The mobile blocking forces were interfering with Viet Cong supply

operations, and the enemy fought back. The resistance was particularly evident

along Routes 4 and 13 as the enemy shifted eastward to avoid the JUNCTION

CITY attacks. In this area three armored battles took place, each illustrating

a different type of combined arms action. The first, at Prek Klok II, stressed

firepower; the second, at Bau Bang, demonstrated mobility and staying power;

and the third, at Suoi Tre, emphasized mobility and shock action.

-

- While mines were not encountered in the first thrust north on Provincial

Route 4, as operations progressed the enemy began to mine the road, hoping

to cut the American force's primary resupply route. From random sniping and

mining the enemy went to mortar attacks and night probes of fire bases. On

the evening of 10 March, Fire Support Base II at Prek Klok II was defended

by Lieutenant Colonel Edward J. Collins's 2d Battalion, 2d Infantry (Mechanized)

, which was minus its Company B, some engineer troops, and two batteries of

105-mm, artillery. The base straddled an airfield that the engineers were

constructing. Tracked vehicles were placed around the perimeter at 50-meter

intervals, and artillerymen, engineers, and infantrymen manned foxholes between

the APC's. About 2030 a listening post sighted three Viet Cong and immediately

pulled back into the perimeter; the base went to 75 percent alert status.

An unearthly silence fell. Some thirty minutes later it was broken by the

dull thump of enemy mortars firing. In a matter of seconds the entire area

erupted with explosions as the enemy poured over 200 rounds of mortar and

recoilless rifle fire into the base. When the barrage ended, Colonel Collins

ordered the de-

- [96]

- fenders to conduct a reconnaissance by fire of the area 200 to 600 meters

beyond the perimeter.2

-

- When the U.S. machine guns fell silent at 2220, the enemy launched a two-battalion

ground attack from the east. The first wave of the assault came within hand

grenade range, and the perimeter was enveloped in fire as the defenders answered

with vehicle-mounted and ground machine guns, small arms, and artillery fire.

Intense Viet Cong antitank fire, rocket propelled grenades and recoilless

rifles, was directed against the APC's. Although the vehicles were positioned

behind a low berm, three were struck by rocket grenades and one received a

direct hit from a mortar round.

-

- To support the main attack, smaller enemy forays were launched from the

northeast and southeast. Trip flares and listening posts had been set out

about fifty meters in those areas. According to Specialist 4 Thomas Lark,

when the listening posts were brought in after the mortar attack, "We

opened up on the VC when they hit our trip flares and after that we never

had any trouble with the VC getting close to our perimeter." A secondary

attack was also launched from the southwest, but here the enemy had to cross

500 meters of open ground. Amid explosions of recoilless rifle rounds, the

defenders held their positions, pouring machine gun and small arms fire into

the attackers. This secondary attack never gained momentum, although heavy

enemy fire continued from the wooded area beyond the clearing. Supported by

air strikes, artillery, and machine gun fire from "Spooky" (a C-47

aircraft with multi-barrel machine guns) , the defenders repelled the brunt

of the attack by 2300.

-

- The battle of Prek Klok II was one-sided, for the enemy lost almost 200

men while the defenders lost three. The enemy had hoped to achieve a quick

victory to bolster his sagging fortunes. Instead, a combined arms team of

artillerymen, mechanized infantrymen and aircraft, using selective firepower

and properly prepared defensive positions, had dealt him a severe defeat.

-

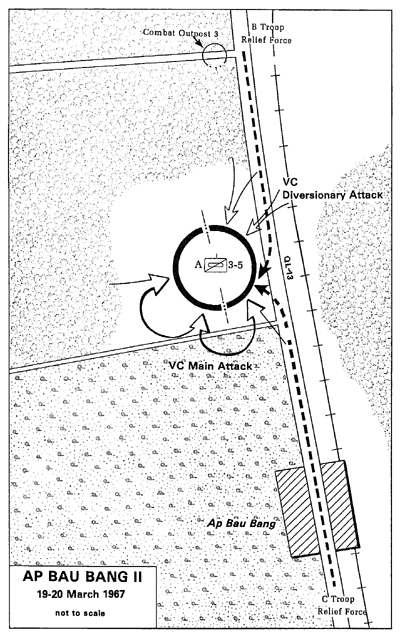

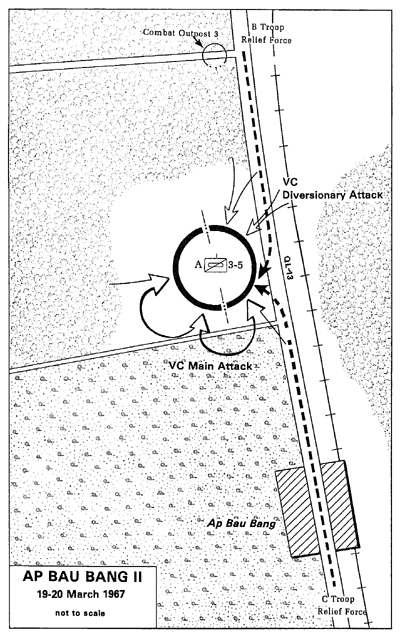

- As JUNCTION CITY continued into Phase II, the enemy lost enormous amounts

of supplies and was denied use of his vital communications centers. In an

attempt to ease the pressure, the Viet Cong launched a desperate attack on

19 and 20 March against a fire base protected by the cavalry. The base, sixty

kilometers north of Saigon near Ap Bau Bang on QL-13, was in flat country

- [97]

- MAP 9

- [98]

- with wooded areas to the north and west and a rubber plantation to the south.

(Map 9) It was protected by Troop A, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry Regiment,

and contained Battery B, 7th Battalion, 9th Artillery (105-mm.) One platoon

from the troop occupied Combat Outpost 3, approximately 2,800 meters north.

Troop B of the 3d Squadron was located to the north, and Troop C and the headquarters

troop were protecting the squadron command post to the south.

-

- At 2300 the northeast section of the fire support base was raked by fire

from an enemy machine gun, but the gun was quickly silenced by return fire

from tanks and armored cavalry assault vehicles. Shortly after midnight the

base came under heavy fire from rocket grenades, mortars, and recoilless rifles,

followed by a massed ground assault. Main attacks from the southwest and southeast

were supported by a diversionary attack from the northeast. Troop A defenders

at first held their own but requested that a ready reserve force be designated

for use if needed. The 1st Platoon of Troop B, to the north, and the 3rd Platoon

of Troop C, in the south, were alerted to assist.

-

- The battle intensified as enemy troops reached the vehicles on the

southwest portion of the perimeter, but with the help of more than

2,500 rounds of sustained artillery fire from all calibers of weapons the

cavalry held. At times enemy soldiers were blasted off ACAV's by 90-mm. canister

fire from nearby tanks. When the tanks ran out of canister, they fired high

explosive rounds set on delayed fuses into the ground in front of the enemy.

The result was a ricochet round that exploded overhead and showered fragments

over the enemy units - a very effective weapon. Several defending vehicles

were hit and destroyed by rocket grenade fire, and the gaps created in the

line finally forced the troop to fall back to tighten its perimeter.

-

- At 0115 the squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel Sidney S. Haszard, gave

Troop A permission to move its 2d Platoon from Combat Outpost 3 to the fire

base, and ordered Troops B and C into action. The 2d Platoon had to attack

the enemy in order to get through to the defenders. When the 3d Platoon of

Troop C arrived, the Troop A commander directed that it sweep south of the

perimeter along the tree line. Continually firing its weapons, the

platoon swept the southwest side of the fire base, then doubled back and entered

the defensive line from the southeast. At the same time, while en route to

the base at thirty miles an hour, the 1st Platoon of Troop B literally ran

over a hastily set ambush. Just as the platoon arrived, the enemy launched

another attack. The Troop A com-

- [99]

- mander directed it to sweep the entire perimeter. Circling around the outside

of the base with headlights and searchlights flashing and weapons firing,

the platoon crushed the attack.

-

- The enemy's next attack, at 0300 from the south, was easily repelled by

the five cavalry platoons in the base and air support that eventually totaled

eighty-seven sorties through the night. Troop A then conducted a series of

counterattacks, clearing an area 800 meters deep around the perimeter and

reducing the enemy fire. At 0500 under illumination from flares and searchlights,

the enemy could be seen massing for another attack from the south and southeast.

Tactical aircraft and artillery were quickly employed and the attack never

gained momentum. Although sporadic enemy fire continued, the six-hour battle

ended, leaving over 200 enemy dead on the battlefield and three American soldiers

killed.

-

- The success of the defense hinged on the mobility of the armored units,

the heavy firepower-artillery and air support- and the tactics used. The armored

vehicles had not been dug in and were not fenced in with wire. Throughout

the attacks, ACAV's and tanks continuously moved backward and forward, often

for more than twenty meters, to confuse enemy gunners and meet attacks head

on. The movement added to the shock effect of the vehicles, for none of the

enemy wanted to be run over. In addition, reinforcing platoons all carried

extra ammunition on their vehicles and provided resuppy during the battle.

-

- The last major armored action in JUNCTION CITY occurred only a day after

the Ap Bau Bang fight, when the enemy launched an unprecedented daylight attack

against Fire Support Base Gold near Suoi Tre. The fire base was occupied by

the 3d Battalion, 22d Infantry (-) and the 2d Battalion, 77th Artillery (-)

. The 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry, the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, and the 2d

Battalion, 22d Infantry (Mechanized), were conducting search and destroy operations

nearby.

-

- The 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Stailey,

moved north on 20 March, led by Company A, 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry, which

had been sent to link up with the tanks. By nightfall the two battalions had

joined and set up camp within two kilometers of each other. Earlier that afternoon

the Scout platoon of the mechanized battalion had cleared a trail about 1,500

meters to the north but had been unable to locate a ford across the Suoi Samat.

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph W. Julian, commander of the 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry,

decided that the next day his units would move north on the trail, then swing

east to search for a ford across the upper reaches of the stream.

- [100]

- On the opposite side of the Suoi Samat, about two kilometers northeast of

the tank battalion's position, infantrymen and artillerymen were improving

perimeter defenses at Fire Support Base Gold. The next morning at 0630, an

ambush patrol from the 3d Battalion, 22d Infantry, engaged a large force of

Viet Cong moving toward the base and at the same time the base came under

heavy mortar attack. Over 600 rounds pounded the camp as waves of Viet Cong

emerged from the jungle, firing recoilless rifles, rocket grenades, automatic

weapons, and small arms. The ambush patrol was quickly overrun and was unable

to return to the base. As the fighting grew more intense, the armored units

to the south were ordered across the Suoi Samat to reinforce the embattled

fire base. Colonel Julian immediately moved part of Company C and an attached

tank platoon north on the trail cleared earlier by the Scout platoon.

-

- While the remainder of the column closed, conditions worsened at the fire

base. Colonel Marshall Garth, the brigade commander, said "If a vehicle

throws a track, leave it. Let's get in there and relieve the force."

Personnel carriers in the lead straddled each other's paths in order to clear

a trail wide enough for tanks, while lead elements using compasses continued

their search to the east in an attempt to find the Suoi Samat and a ford.

-

- At Fire Base Gold, counter fire was seeking out the enemy mortars that were

pounding the defenders. The enemy concentrated against the east side of the

perimeter until, at 0711, Company B reported that its 1st Platoon had been

overrun. A reserve force of artillerymen helped to reestablish the perimeter,

but fortyfive minutes later the enemy had again broken through the 1st Platoon.

Within a few minutes, positions on the northeastern portion of the Company

B perimeter were completely overrun by a human wave attack. Company A sent

a force with desperately needed ammunition to assist Company B. Then, on the

northern perimeter, the Viet.Cong swarmed over a quadruple .50-caliber and

attempted to turn it on the defenders, but the weapon was blown apart by the

artillery. To make matters worse, Company A reported penetrations in portions

of its northern perimeter.

-

- The urgency of the situation was again conveyed to Colonel Julian by Colonel

Garth's order that the stream was to be crossed "even if you have to

fill it up with your own vehicles and drive across them." Following instructions

from a helicopter overhead, the armored column finally crossed the stream

and moved toward the fire base. To the northwest the 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry,

advancing on foot, had reached the defenders. From the air, Colonel Julian

directed Lieutenant Colonel Joe Elliot, Commander of the

- [101]

- 2d Battalion, to secure the western sector of the fire base. The mechanized

forces were ordered to enter just south of the 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry,

and swing around the perimeter, consolidating the remainder.

-

- On the smoke-covered battlefield the reinforced defenders were still in

desperate straits. Artillerymen were firing beehive rounds, steel flechettes

released at the muzzle of the weapon. When the supply of beehive was exhausted,

they switched to high-explosive direct fire at point-blank ranges. The eastern

sector of the perimeter had fallen back under heavy pressure to positions

around the artillery pieces. The Viet Cong were within five meters of the

battalion aid station and within hand grenade range of the command post.

-

- Into this chaos came the tanks and APC's, crashing through the last few

trees into the clearing. The noise was overwhelming as the new arrivals opened

up with more than 200 machine guns and 90mm. tank guns. The ground shook as

tracked vehicles moved around the perimeter throwing up a wall of fire to

their outside flank. They cut through the advancing Viet Cong, crushing many

of them under the tracks. The Viet Cong, realizing that they could not outrun

the encircling vehicles, charged them and attempted t0 climb aboard but were

quickly cut down. Even the tank recovery vehicle of Company A, 2d Battalion,

34th Armor, smashed through the trees with its machine gun chattering. Most

of the crew, who were all mechanics, were throwing grenades, but one calm

mechanic sat serenely atop the vehicle, his movie camera grinding away.

-

- Relief was evident in the faces of the defenders as tracked vehicles quickly

tied in with the 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry. "It was," exulted

Lieutenant Colonel John A. Bender, the fire base commander, "just like

the late show on TV, the U.S. Cavalry came riding to the rescue." Master

Sergeant Andrew Hunter recalled, "They haven't made the word to describe

what we thought when we saw those tanks and armored personnel carriers. It

was de-vine." With victory almost within grasp of the enemy, the tanks

and APC's had turned the tide. When the smoke cleared, it was apparent that

the enemy had not only been defeated but had lost more than 600 men.

-

- JUNCTION CITY II ended on 15 April as the enemy faded away. Armored units

played a major role in JUNCTION CITY and proved that in most areas

of War Zone C, a cavalry squadron or mechanized infantry battalion could more

effectively control a large area than any other type of unit. Although routes

over the difficult terrain had to be carefully selected, tracked units moved

through most

- [102]

- of the dense jungled area. Tanks were invaluable in breaking trails through

seemingly impenetrable vegetation. The ability of armored forces to move rapidly

and to arrive at the critical place with great firepower gave them a significant

advantage.

-

- Mechanized Operations in the Mekong Delta

-

- The extensive rice paddies and mangrove swamps of the canal laced delta

were very different from the jungled areas of Operation CEDAR FALLS-JUNCTION

CITY in III Corps Tactical Zone. But in the delta, with few high elevations,

M113's could move as freely as rivers and major canals permitted. The 2d Battalion,

47th Infantry (Mechanized) , and the 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry (Mechanized)

, of the U.S. 9th Infantry Division-two armored units employed in this region-conducted

successful combined American-Vietnamese operations throughout 1967. Typical

missions included reconnaissance in force, route and convoy security, night

roadrunner operations, cordon and search of villages, and rapid reinforcement.

-

- Flooded rice paddies slowed, but did not prevent cross-country movement.

Small canals up to three meters in width were crossed with balk bridging.

In the case of larger canals and rivers, which were major obstacles because

their banks were usually steep or composed of loose soil, bulldozers or explosives

were used to construct entry and exit routes. Mechanized units quickly discovered

that when track shrouds were removed to prevent the buildup of mud between

track and hull the M113's swimming ability was impaired. Navy landing craft

were therefore required for transportation across major rivers and canals.

Route reconnaissance by air was always important but was essential during

the monsoon season.

-

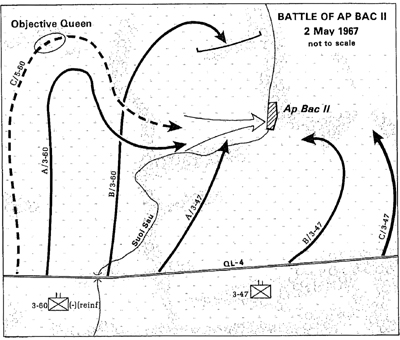

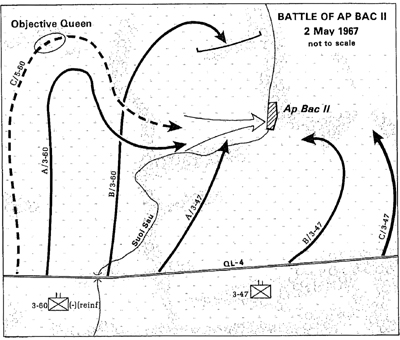

- The delta's open, level terrain permitted ground troops to engage with organic

weapons at much greater range than that of the point-blank fighting normal

in the jungle. One of the hardest battles fought by mechanized infantry in

the delta occurred at the village of Ap Bac II on 2 May 1967. Ap Bac II was

a base area for the 514th Viet Cong Battalion, and the enemy pattern of movement

between base areas had suggested the probability of the battalion's presence

near Ap Bac II on 2 May.

-

- The original plan of the 2d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division, was to conduct

an airmobile search and destroy operation with two battalions of infantry.

On 2 May, however, when no helicopters were available the insertion of a blocking

force was deleted from the plan. Movement of two battalions abreast without

a blocking force in the rear was regarded by many as "forcing toothpaste

- [103]

- MAP 10

-

- from a tube," and there appeared little likelihood of a significant

encounter. Company C, 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry (Mechanized) , manned the

left flank under the control of the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry. (Map 10)

First Lieutenant Larry Garner's mechanized company was given the deeper objective

because its mobility would permit a quick search of the area. It was hoped

that tracked vehicles could make up for lack of a blocking force.

-

- By 0830 the M113's of Company C were advancing north, crossing paddies surrounded

by narrow, earthen dikes. Mostly dry, the paddies easily supported tracks,

but crossing the many canals and streams proved more difficult. Company C

found none of the enemy during its northward sweep; however, to the east,

Company A, 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, encountered stiff resistance as it

approached the Suoi Sau. The steep banks of the stream were dotted with thatched

huts and lined with dense vegetation. A squad, maneuvering across the stream,

was quickly pinned down by heavy automatic weapons fire. Within minutes all

who had crossed the

- [104]

- stream had been hit. Two companies of the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, moved

in on the right of Company A, while Company B. 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry,

moved to block the northern escape route. At 1300, with blocking forces in

a reversed "C," Company C of the 5th Battalion and Company A of

the 3d Battalion of the 60th Infantry were ordered east to fill the open end

of the blocking positions. The eleven M113's of Company C had to maneuver

through inundated areas that appeared impassable. Crossing two fairly deep

streams, the company chose routes that brought it abreast of Company A, 3d

Battalion, 60th Infantry, on a 1,000 meter assault line by approximately 1530.

Under cover of artillery and air bombardment, the companies crossed more irrigation

ditches and by 1700 were poised for the attack.

-

- On order, artillery fire stopped and the tracked vehicles surged forward,

while blocking units supported by fire. The mechanized company moved rapidly

across the open rice paddy, its machine guns searching out the enemy bunkers

along the wood line. At the woods infantrymen dismounted and attacked the

enemy soldiers who had been pinned down by heavy fire. Although stunned by

the shock of the assault, the Viet Cong continued to resist, and the infantry

was forced to move among the bunkers destroying the enemy with grenades.

-

- Company A, moving on foot to the right of Company C, met heavy resistance

and finally stalled about 100 meters from the bunker line. The company commander

requested help from Company C, which responded by moving four M113's to aid

the dismounted attack. Since darkness had set in, further reinforcement was

considered impractical and the units on hand had to finish the job. Additional

fire support by the M113's, a charge by the attacking companies, and heavy

fire superiority finally broke the enemy's defense. The companies pressed

the attack, forcing the Viet Cong from their bunkers and annihilating those

who tried to escape. A sweep of the battle area early the next morning indicated

that the enemy had lost the equivalent of a reinforced company. Two U.S. soldiers

had died.

-

- Colonel William B. Fulton, the brigade commander, noted that the speed,

shock effect, and heavy firepower provided by the personnel carriers, along

with supporting artillery, had kept the enemy soldiers in their bunkers until

the infantry was literally on top of them. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin W. Chamberlain,

Jr., commander of the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, stated that since the tracked

vehicles proved capable of negotiating more terrain than had been thought

possible, there should always be an initial attempt at

- [105]

-

TANKS AND ACAV'S SECURE SUPPLY ROUTES IN 25TH INFANTRY

DIVISION AREA. Sandbags modify vehicles for security role as movable

pillboxes.

-

- mounted movement in order to capitalize on the additional firepower of the

vehicular-mounted machine guns.

-

- Mechanized infantry units in the delta were extremely flexible and were

used alternately in mechanized, airmobile, and dismounted infantry operations.

First and foremost, however, they were mechanized infantry, capitalizing on

their vehicular mobility to close with the enemy, then dismounting and assaulting,

supported by a base of fire from the vehicles. This is exactly what Company

C had done.

-

- Route Security and Convoy Escort

-

- The missions universally shared by armored units throughout Vietnam were

furnishing route security and convoy escort. Few tasks were more important

than keeping the roads safe and protecting the vehicles, men, and supplies

that used them. At the same time, no task was more disliked by armored soldiers.

When it was done correctly it could be boring, tedious, and in the minds of

many, a waste of time and armored vehicles. When it was done poorly, or when

the enemy was determined to oppose it, it was dangerous, disorganized, and,

again in the minds of many, a one-way ride to disaster.

- [106]

- General Westmoreland's directive had called for opening the roads, making

them safe, and using them. Carrying out the order was a different problem

in each area. In one instance in mid-1966 the task became an intricate, large-scale

operation that led to battles along Highway 13 and the Minh Thanh Road involving

the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry. In another situation in the highlands, a significant

part of the 4th Infantry Division's armored forces-at first the 1st Squadron,

10th Cavalry, and the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, and after September 1967

the 2d Squadron, 1st Cavalry -continuously secured roads throughout the division's

area of operation in the II Corps Tactical Zone.3

In the first three months of 1967, almost 8,000 vehicles a month

under armored protection traversed Highway 19 to Pleiku without incident.

-

- The primary route security technique used in the highlands was to establish

strongpoints along the road at critical locations, and each morning have a

mounted unit sweep a designated portion of the route. The unit then returned

to the strongpoint where it remained on alert, ready to deal with any enemy

action in its sector. When forces were insufficient to man strongpoints twenty-four

hours a day, each convoy using the road was provided with an escort force,

a measure that caused heavy wear on the armored vehicles. Securing roads by

using static positions had the disadvantages that the Viet Cong quickly noted

them and mined all logical vehicle positions with the result that the protective

force soon lost vehicles in the strongpoints. When the 2d Squadron, 1st Cavalry,

was attached to the 4th Infantry Division, the division abandoned the strongpoint

system in favor of offensive patrolling missions several thousand meters from

main routes, a tactic that made a much more effective use of armor.4

-

- Sometimes the security and escort missions were given operational names

and continued for six months or more. One such operation, KITTY HAWK in the

III Corps Tactical Zone, required a cavalry squadron to secure the Blackhorse

Base Camp and the Gia Ray rock quarry, to escort convoys, and to conduct local

reconnaissance in force. (See Map 8.) During 1967 the 3d Squadron,

5th

- [107]

- Cavalry, and a squadron from the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment alternated

in this job. Missions such as this were required throughout Vietnam because

of constant enemy threats.

-

- Occasionally an escort or security mission was not successful, and usually

intensive after action investigation revealed that the unit had been careless.

Such was the case with a platoon of Troop K, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment,

in May 1967. When the smoke cleared from a well-planned Viet Cong ambush,

the platoon had paid a heavy price: seven ACAV's had each been hit 10 times

by antitank weapons and the lone tank had 14 hits. Of forty-four men in the

convoy, nearly half were killed and the remainder wounded. Investigation revealed

that the road had been cleared that morning by a responsible unit, but the

fact that an ambush was set up later proved that it was dangerous to assume

that one pass along a road cleared it of enemy forces. In this case there

were further errors of omission. No planned platoon action was put into effect

when the enemy attacked; no command and control alternatives were provided

in the event of a loss of radio communication; no signals or checks were in

effect to alert troop headquarters to the platoon's plight; no artillery or

air support was planned for the route of march. The lesson from this disaster

was that no mission should be considered routine.

-

- Disasters were uncommon to road security missions, but much could be learned

from them. On one occasion the law of averages, troop turnover, and the boredom

of a routine task caught up with the 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, while it was

on road security. This incident in late December 1967 illustrates how overconfidence,

poor planning, and lack of fire support could combine to strip the cavalry

of its inherent advantages. On 22 December the squadron was to assume responsibility

for Operation KITTY HAWK. The squadron staff prepared its plans for convoy

escort, with convoys scheduled to move on 27 and 31 December. At the last

moment, the 3d Squadron's assumption of the KITTY HAWK mission was delayed

until 28 December and the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment performed the escort

duty on 27 December. The two-day delay caused the staff of the 3d Squadron,

5th Cavalry, to be less attentive to the second convoy escort mission on the

31st.

-

- On 28 December the 3d Squadron moved into Blackhorse Base Camp, and the

next day the squadron operations officer was reminded of the responsibility

for the escort on 31 December. Mission requirements were discussed over insecure

telephone lines by the staffs of the squadron and the 9th Infantry Division,

and were then passed to Troop C, which had the mission. The squadron daily

staff

- [108]

- briefing on 30 December did not include a discussion of the escort mission

and the squadron commander remained unaware of it. The Troop C commander,

familiar with the area, believed the sector to be relatively quiet, a fatal

assumption because combat operations had not been conducted in the area for

over thirty days. He planned a routine tactical road march to Vung Tau, sixty

kilometers to the south, to rendezvous with the convoy at 0900 on 31 December.

Two platoon-size elements were to make the march while the troop commander

remained at Blackhorse with the third platoon, ready to assist if needed.

The platoons were to leave Blackhorse at 0330 on 31 December, moving south

on Route 2. One platoon was to stop along Route 2, about a third of the way

to Vung Tau, and spend the night running the road back to Blackhorse to prevent

enemy interference on the route. The other platoon was to continue to Vung

Tau, pick up the convoy, and escort it to Blackhorse. The convoy would be

rejoined en route by the platoon conducting roadrunner operations.

-

- The column moved out on time to meet the convoy. The lead platoon, commanded

by the 2d Platoon leader, consisted of one tank from the 3d Platoon, 'two

ACAV's from the 2d, and the troop command and maintenance vehicles employed

as ACAV's. The next platoon, commanded by the 3d Platoon leader, consisted

of one tank from the 2d Platoon, two ACAV's from the 3d Platoon, two from

the 1st Platoon, and the 1st Platoon's mortar carrier minus its mortar. The

tanks, each leading a platoon, intermittently used driving lights and searchlights

to illuminate and observe along the sides of the road.

-

- About nine kilometers south of Blackhorse, Route 2 crested a slight rise,

ran straight south for two kilometers, and then crested another rise. The

sides of the road had been cleared out to about 100 meters. As the lead tank

started up the southernmost rise at 0410, the last vehicle in the convoy,

the mortar carrier, was leveling off on the straight stretch two kilometers

behind. Suddenly a rocket propelled grenade round hit the lead tank, killing

the driver and stopping the tank in the middle of the road. An ambush then

erupted along the entire two-kilometer stretch of road. A hail of grenades

quickly set the remaining vehicles of the lead platoon afire; intense small

arms fire killed most of the men riding atop the vehicles. As the trailing

platoon leader directed his platoon into a herringbone formation, the mortar

carrier was hit by a command detonated mine, exploding mortar ammunition and

destroying the carrier. The tank with the last platoon was hit by a rocket

grenade round, ran off the road, blew up, and burned. The surprise was so

- [109]

-

OH-6A OBSERVATION HELICOPTER AND TWO AH-1G COBRAS EN ROUTE

TO CONDUCT VISUAL RECONNAISSANCE NEAR PHUOC VINH

-

- complete that no organized fire was returned. When individual vehicles attempted

to return fire, the enemy, from positions in a deadfall some fifteen meters

off the road, concentrated on that one vehicle until it stopped firing. Within

ten minutes the fight was over.

-

- At daybreak on the last day of 1967, the devastating results of the ambush

were apparent in the battered and burned hulks that lay scattered along the

road. Of eleven vehicles, four ACAV's and one tank were destroyed, three ACAV's

and one tank severely damaged. The two platoons suffered 42 casualties; apparently

none of the enemy was killed or wounded. This costly action showed what could

happen on a routine mission in South Vietnam. Indifference to unit integrity,

breaches of communication security beforehand, lack of planned fire support,

and wide gaps between the vehicles stacked the deck in the enemy's favor.

Charged with guarding a convoy, the unit leader failed to appreciate his own

unit's vulnerability.

-

- Elsewhere in the III Corps Tactical Zone other U.S. units were performing

similar route and convoy security missions. The 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

25th Infantry Division, operated almost

- [110]

- continuously along Route 1 from Saigon to Tay Ninh. The squadron's air cavalry

troop worked with it, providing first and last light reconnaissance along

main routes. By mid-1967 the squadron was escorting an average of 8,000 vehicles

per month. In late summer it began so-called night thrust missions sending

out mock convoy escorts at night to test the enemy reaction. After a month-long

test without significant enemy action, the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, began

escorting night logistical convoys from Saigon to Tay Ninh, a mission that

continued through 1967.

-

- Air Cavalry Operations

-

- As a necessary complement to ground armored forces, air cavalry units brought

a new dimension to the Vietnam conflict. The first air cavalry unit, the 1st

Squadron, 9th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, exploited the concept and literally

wrote the book on air cavalry operations. Few other air cavalry units, particularly

those with divisional cavalry squadrons, were assigned air cavalry roles at

first; instead, they were used to escort airmobile operations-like armed helicopter

companies. After the armor study and the assignment of more experienced and

innovative commanders, air cavalry troops finally began to operate in air

cavalry missions.5

Quite often, however, rotation of commanders, particularly senior

commanders, required that lessons be relearned time and again. There was thus

a continuing discussion on the proper role and the command of air cavalry

units.

-

- In units that properly used air cavalry, operations followed a daily pattern.

Upon receipt of information indicating enemy activity, an air reconnaissance

was conducted by the troop to determine whether or not further exploitation

by ground forces was required. If ground reconnaissance was desirable, the

troop commander usually committed his aerorifle platoon. A standby reserve

force could be called by the troop commander if the situation required. The

air cavalry troop commander controlled all reaction forces until more than

one company from a supporting unit was committed. At that time control passed

to the commander responsible for the area, and the operation was conducted

like a typical ground or airmobile engagement, often with the air cavalry

remaining in support. Major General John J. Tolson, Commander, 1st Cavalry

- [111]

- Division, clearly stated his feelings about air cavalry: "I cannot

emphasize how valuable this unit [1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry] has been to me

as division commander. Over 50 percent of our major contacts have been initiated

by actions of this squadron."

-

- To be successful, air cavalry operations had to be swiftly followed by ground

or airmobile elements of the division or regiment. Unfortunately in many units

with air cavalry, reported leads were frequently not followed up. Consequently,

many air cavalry units adopted the unofficial practice of developing leads

that could be handled by the air cavalry itself.

-

- In October 1967 two air cavalry squadrons, the 3d and 7th Squadrons, 17th

Cavalry, arrived. Because they were the first units of their type to be assigned

to U.S. infantry divisions in Vietnam, their integration into the force was

accomplished with some difficulty. Most problems reflected a lack of knowledge

on the part of the division commander and staff concerning capabilities, limitations,

and basic support needs of air cavalry squadrons. There was an unfortunate

tendency to use the aircraft for command and control and for transportation

in airmobile operations rather than for reconnaissance. At the outset, therefore,

air cavalry was not used to best advantage, and there was some misuse. Only

after commanders became more aware of the capabilities of their air cavalry

squadrons was proper employment achieved, and in some cases the process was

slow and painful.6

-

- Other Free World Armor

-

- As early as April 1965, discussions had been held on the deployment to Vietnam

of armored units from other nations. Surprisingly, the impetus for such discussion

came from Ambassador Maxwell Taylor, and centered on the proposed use of a

tank company from New Zealand. At the Honolulu Conference in April 1965 this

proposal was disapproved, but by September when the Australian task force

arrived an armored personnel carrier troop was included. Equivalent to a reinforced

American platoon, the troop was quickly put to work with the U.S. 173d Airborne

Brigade. In October free world armor strength increased when the Republic

of the Philippines sent a security force of seventeen APC's and two M41 tanks.

-

- The Royal Thai Army forces that arrived in Vietnam in 1967 brought with

them an M113 platoon and a cavalry reconnaissance

- [112]

-

TROOPS OF 1ST AUSTRALIAN ARMOR REGIMENT IN FRONT OF AUSTRALIAN

CENTURION TANK receive briefing at Vung Tau.

-

- troop. By 1969 this force had been increased to three cavalry troops and

a total of over 660 armor soldiers. The Koreans asked permission to deploy

a tank battalion, but the request was disapproved in midsummer 1965 on the

grounds that the area was inappropriate for tanks. Later, Korean and American

tank-infantry operations in the area enabled the Koreans to acquire APC's

on permanent loan from the United States, and these were employed as ACAV's.

Finally, in 1968, the Australians sent twenty-six Centurion tanks and an additional

cavalry platoon. The Centurions, the only tanks other than U.S. tanks used

in Vietnam by the free world forces, had 84-mm. guns and successfully operated

east of Saigon near Vung Tau.

-

- Although the armored units were small, they represented a significant proportion

of each country's contribution. Their presence, moreover, showed a strong

inclination on the part of these countries, particularly those in Asia, to

use armored units anywhere as part of a combined arms team. A balanced combat

force was their goal regardless of the nature of the terrain.

- [113]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-