- Chapter V:

-

- Three Enemy Offensives

-

- By late 1967 it appeared that the continued pressure of American and other

free world forces in offensive operations and the South Vietnamese armed forces

in pacification would eventually prevail. Enemy documents captured later indicated

that the enemy had reached approximately the same conclusion and was so concerned

about the outcome of his operations that he had decided to begin a general

offensive to decide quickly the fate of South Vietnam. The new campaign was

designed to inflict heavy losses on free world units and to destroy the South

Vietnamese Army. The first objective was to launch a massive attack on all

urban population centers and to seize and hold as many of them as possible.

The enemy expected this offensive to be followed by a popular uprising that

would reinforce Viet Cong and North Vietnamese units with deserting South

Vietnamese troops.

-

- Enemy Buildup

-

- As early as the fall of 1967, intelligence sources had reported an increase

in enemy road construction along the infiltration routes that crossed the

border. In late fall the free world forces captured a document that described

the enemy plan in general terms, but did not specify the timing. Large numbers

of enemy troops and quantities of supplies were meanwhile being slipped into

Saigon, Hue, and other cities as the South Vietnamese prepared to celebrate

the lunar New Year, Tet, on 31 January 1968, welcoming the Year of

the Monkey. Tet is both a solemn and joyous occasion; it is observed

each year with exploding fireworks, feasts of rice cakes and other delicacies,

and traditional visits to home villages. Enemy soldiers mingled easily with

the crowds of holiday travelers and, aided by a well-organized network of

agents, entered the cities.

-

- There were other signs of an impending enemy offensive: captured members

of the Viet Cong stated that the country would be "liberated" by

Tet, and there was a sharp drop in the number of enemy deserters. Nearly

forty attacks took place against outposts and towns in the upper Mekong Delta,

where the Viet Cong often tested new tactics. By 24 January General Westmoreland,

certain that the enemy would violate any Tet truce, had persuaded the

U.S. and South Vietnamese governments to cancel a truce in the I Corps

- [114]

- Tactical Zone. Lt. Gen. Frederick C. Weyand, now commander of the II Field

Force, Vietnam, was also concerned because units along the Cambodian border

in the III Corps Tactical Zone were not having as many encounters with the

enemy as they usually did. With General Westmoreland's approval, he shifted

American forces back toward populated areas to improve close-in protection.

By the eve of Tet, twenty-seven U.S. maneuver battalions were inside

the so-called Saigon circle, within a 45-kilometer radius of Saigon; twenty-two

maneuver battalions remained outside that radius.1

-

- On 29 January cancellation of the truce in the I Corps Tactical Zone was

announced. That night many free world bases in the I and II Corps zones were

attacked. The next day the Tet truce was officially canceled throughout

the country, and commanders were ordered to place troops on maximum alert

and to resume offensive operations.

-

- Before Tet armored units in all four corps tactical zones were in

position to counter possible enemy attacks. American armored units had been

shifted away from cities and were in position to block infiltration routes

and quickly meet any major enemy attack. Vietnamese armored forces were stationed

in or near cities to provide protection against anticipated attacks on population

centers. Although on alert, the troops in the field expected nothing more

than the usual attacks by indirect fire and occasional ambushes or probes.

But the one flaw in the preparations was that no one, riot even the staff

at the Military Assistance Command, expected an attack of the magnitude and

scope that developed in the first enemy offensive of 1968. At high command

levels in Vietnam the attack had all the impact of the German Ardennes

offensive of World War II.

-

- For South Vietnamese and free world armored forces the battles of 1968 marked

the acceptance of armor as an asset to the fighting forces in Vietnam. That

acceptance was won on the battlefield by a demonstration of mobility and firepower

that silenced all critics. When the enemy forced free world forces to move

rapidly from one battle area to another, it was the armored forces that covered

the ground quickly and in many cases averted disaster. Rapid movement was

imperative in the early stages of the enemy attack, and the armored units

were the first ground forces to reach the battlefield in almost every major

engagement, although the winning of the battles eventually involved all forces.

The story of these battles

- [115]

- points to the value of armored units as reaction forces. There was no set

plan on the free world side in the early stages of the enemy attack; to defend

was the purpose and armored forces made a substantial contribution to that

defense. The three battles of the Tet offensive of 1968 described here

serve as illustration of all the others in which armored units fought as the

major counterattack force. One was a U.S. cavalry action, another a U.S. mechanized

infantry battle, and the last a South Vietnamese cavalry attack. All three

demonstrate the value of mobility and armor-protected firepower when they

are aggressively used.

-

- First Offensive: Tet 1968

-

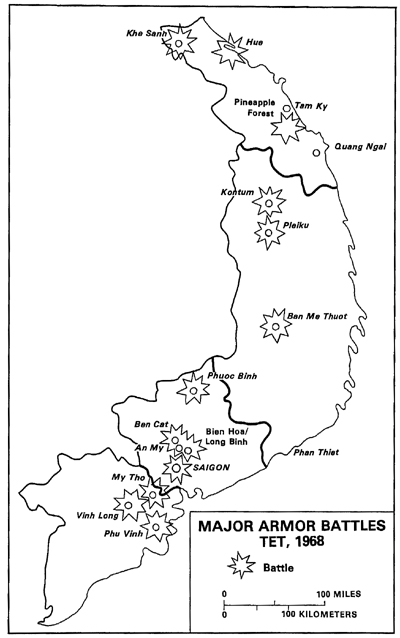

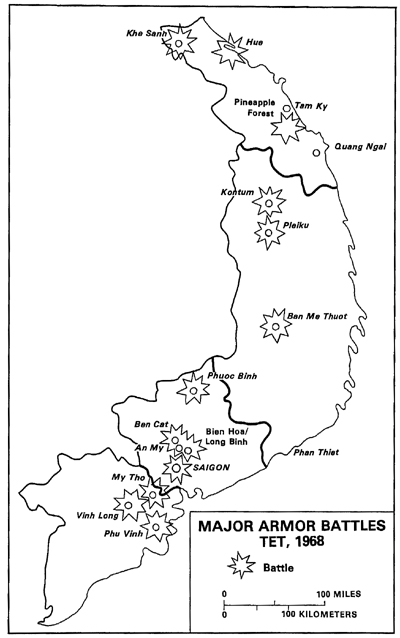

- The early attacks in I and II Corps Tactical Zones on 29 January signaled

to free world forces that the enemy offensive had begun. In northern I Corps,

where Khe Sanh was beleaguered, the few available armored elements were used

inside the base to reinforce weak points in the perimeter and to repulse enemy

ground attacks. During the relief of Khe Sanh, air cavalry units played a

major role in finding the enemy, adjusting supporting fire, and keeping continuous

pressure on the enemy. (Map 11) Air cavalry reconnaissance was so successful

that no helicopters were lost during the airmobile assaults of the relief

forces.

-

- Farther south, the South Vietnamese armored forces broke up an attack on

Quang Ngai City; by acting quickly with overwhelming firepower they drove

the enemy from the city in less than eight hours. In a two-day battle in what

was known as the Pineapple Forest near Tam Ky later in February, ground and

air cavalry units killed some 180 of the enemy and had only one cavalryman

wounded. Air cavalry elements found and fixed the enemy forces while ground

cavalry attacked and destroyed them.

-

- In Hue, the ancient capital of Vietnam, air cavalry, ground cavalry, U.S.

Marine armor, and South Vietnamese armor participated in the longest battle

of Tet, which lasted twenty-six days. The fighting, confined to a thickly

populated area, was sustained and intense. Tank crews were so shaken by multiple

hits from rocket propelled grenades-as many as fifteen on some tanks-that

crews were changed at least once a day. Armored units were in constant demand

and often expended their vehicle ammunition loads in a few hours. Their support

of the infantry and marines, who cleared the city, provided the firepower

advantage.

-

- While battles were raging in I Corps Tactical Zone the highlands and coastal

plain in II Corps were also under heavy attack.

- [116]

- MAP 11

- [117]

- Pleiku withstood Viet Cong assaults for five days, thanks primarily to the

combined arms teams defending the city. Tankers, cavalrymen, artillerymen,

and engineers from American units fought side by side with South Vietnamese

cavalry and infantry. Near the border between II and III Corps, South Vietnamese

cavalrymen traveled 100 kilometers through ambushes in eleven hours to the

seacoast city of Phan Thiet, where they battled for eight days. South Vietnamese

cavalrymen fought in Ban Me Thuot, and there again their firepower and aggressiveness

was a deciding factor. The battle for the provincial capital of Kontum in

II Corps involved both American and South Vietnamese cavalry and tanks. Before

this battle, Troop A, 2d Squadron, 1st Cavalry, had planned and rehearsed,

down to squad level, various strategies for the defense of Kontum; several

of these were swiftly put into effect shortly after the attacks began.

- The one-day warning provided by attacks in the north were barely enough

time to alert units in the III Corps Tactical Zone when the full fury of the

offensive erupted in the Saigon area. Armored units participated in all major

battles in III Corps, and in thirty-seven out of the seventy-nine separate

engagements. At Thu Duc, a Saigon suburb, a cavalry task force of students

and faculty from the South Vietnamese Armor School defeated the enemy in bitter

street fighting. On 1 February U.S. cavalry and infantry met a large enemy

force at An My, north of Saigon. In a two-day battle this combined arms team

mauled elements of a Viet Cong regiment. In the battle of Ben Cat, U.S. cavalry

platoons converged on the town from two directions during a night attack and

drove the enemy away. Mechanized infantrymen cleared the enemy from the racetrack

in the center of Saigon, and in an afternoon and evening battle in a cemetery,

fighting hand-to-hand among the tombstones, they killed 120 of the enemy.

It was in the suburbs of Saigon, however, that the fighting in III Corps reached

a climax; it was there, in the critical approaches, that cavalry and mechanized

infantry decided the fate of the city.

-

- Battle of Tan Son Nhut

-

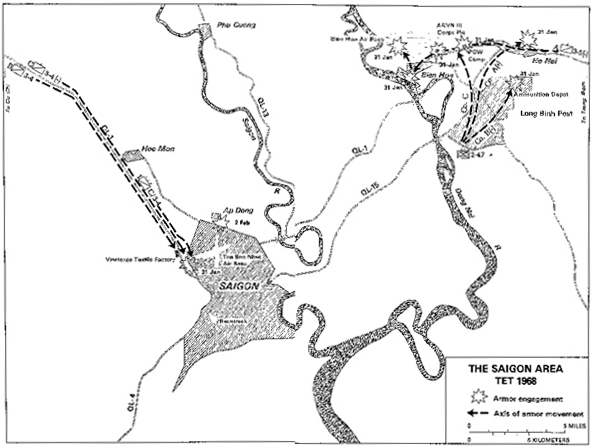

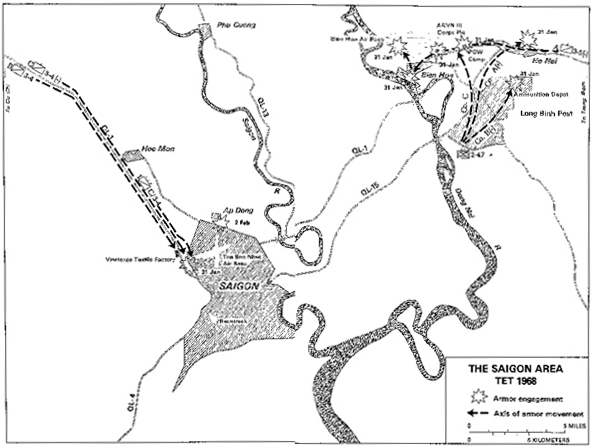

- About 2100 on 30 January, Lieutenant Colonel Glenn K. Otis, commander of

the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, was ordered to send one troop to aid Tan Son

Nhut Air Base on the north side of Saigon. (Map 12) Colonel Otis directed

the Troop C commander, Captain Leo B. Virant, to prepare for this mission

and to put his troops on short notice alert. Troop C was at Cu Chi, twenty-five

kilometers northwest of Saigon, with one of its platoons securing

- [118]

- the Hoc Mon bridge, ten kilometers closer to Saigon on National Highway

1.

-

- At 0415 Colonel Otis was ordered to commit Troop C to block a Viet Cong

regiment that had attacked Tan Son Nhut Air Base. The troop was on its way

in fifteen minutes and while it was en route was ordered to destroy enemy

forces attacking the air base itself. Troop C was to be under the operational

control of the Tan Son Nhut commander; a guide from that headquarters was

to meet the unit at the south side of the Hoc Mon bridge and lead it to the

air base. To avoid ambushes along Highway QL-1, Colonel Otis flew over the

unit and, dropping flares to discourage the enemy, guided it cross-country

to the Hoc Mon bridge. Troop C then passed through its own 1st Platoon, which

remained at the bridge, met the guide from Tan Son Nhut, and moved toward

the air base. Colonel Otis returned to Cu Chi to refuel and rearm.

-

- The only information provided to Troop C was that a large enemy force had

attacked from west to east across Highway 1 and penetrated the airfield defenses.

As the troop approached the air base about 0600, it came under heavy small

arms, automatic weapons, and rocket grenade fire. The cavalrymen attacked

to split the enemy force where Highway 1 passed the southwestern gate of Tan

Son Nhut. This move isolated approximately 100 Viet Cong inside the air base

and kept the main body outside the gate. The full brunt of the enemy attack

now fell on Troop C. In the first few minutes several tracked vehicles were

hit and troop casualties were heavy. Captain Virant was seriously wounded

in the head. The remaining elements of Troop C kept firing and succeeded in

slowing the assault, but enemy fire forced some members of the troop out of

their damaged vehicles into a ditch alongside Highway 1. Unable to communicate

with the air base, the troop called the squadron at Cu Chi for help.

-

- Colonel Otis was present when the call came in and immediately started back

to Tan Son Nhut, calling 25th Infantry Division headquarters for release of

Troop B from its mission of guarding the Trang Bang bridge, fifteen kilometers

northwest of Cu Chi. Instead, the 1st Platoon, Troop C, was released from

the Hoc Mon bridge, and Colonel Otis directed it to move to Tan Son Nhut immediately.

In addition, he ordered the squadron's air cavalry troop to support Troop

C. Flying over the area, Colonel Otis observed Troop C deployed in an extended

column formation along Highway 1, with four tanks and five personnel carriers

burning. Even from the air, he could see that the unit was hard pressed.

-

- Ammunition was running low in Troop C when the air cavalry

- [119]

- MAP 12

- [120-121]

- helicopters arrived. Gunships immediately attacked the enemy positions,

firing rockets and machine guns. As the last few hand grenades were being

thrown by the ground troops, two helicopters from Troop D, under heavy automatic

weapons fire, landed with ammunition and took off the wounded. At 0715 the

1st Platoon of Troop C arrived. Colonel Otis directed it onto the airfield

and then south to the left flank of Troop C, where it attacked west, relieving

some of the pressure.

-

- Colonel Otis ordered Troop B, commanded by Captain Malcolm Otis, to leave

the Trang Bang bridge and move at top speed down Highway 1 to Tan Son Nhut,

forty-seven kilometers distant. Captain Otis's troop, traveling fast, reached

the battle area in forty-five minutes. When the troop arrived, it executed

a column right toward the west at the Vinatexco Textile Factory, which put

it parallel to the northern flank of the Viet Cong attack. With all vehicles

of Troop B off the main road and strung out in column, Colonel Otis directed

a left flank movement that brought them on line on the flank of what was later

estimated to be at least 600 enemy soldiers. Troop B attacked with such intensity

that many of the enemy immediately fled to escape the fire. Some attempted

to reach a tree line three kilometers to the west across open rice paddies,

but Captain Otis sent his 3d Platoon and Troop D gunships to cut them off.

Caught in a cross fire between Troops B and C and heavy air and artillery

fire, the Viet Cong were pinned in place.

-

- The battle reached a climax at about 1000, when Troop B's flank attack began

to take its toll of the enemy. Although fighting went on until 2200, from

1300 to 2200 the primary business was mopping up-hunting down the confused

and beaten enemy. Subsequent sweeps of the battle area produced over 300 enemy

dead, 24 prisoners, hundreds of enemy weapons of all kinds, and enough equipment

and ammunition to fill a five-ton truck. At 1400 on 31 January, Colonel Otis

was finally able to rendezvous with the Tan Son Nhut command. From the time

Troop C called, asking for help, until 1400, the action was completely independent

of the Tan Son Nhut command, controlled only by the cavalry squadron commander.

-

- The movement of Troop C, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, to Tan Son Nhut Air Base

was a difficult night maneuver that achieved tactical surprise. When the enemy

proved to be more formidable than had been expected, timely reinforcement,

gunship and artillery support, and aerial resupply by units under command

of the squadron turned the tide. The fact that the battle was fought by one

unit and directed by one commander greatly facilitated con-

- [122]

- trol, but the deciding factor was the cavalry firepower that dominated the

action.

-

- Colonel Otis's cavalrymen were to have no rest after Tan Son Nhut, for the

3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, was soon involved in its second major battle in

as many days. This time it had help from Troop A, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

which, after constant fighting throughout Saigon, was sent to Tan Son Nhut

under operational control of the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry. Shortly after daybreak

on 2 February, the 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry, the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

and Troop A, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, were ordered to conduct a reconnaissance

in force through Ap Dong, a village north of Tan Son Nhut. Following tactical

air strikes and an artillery preparation, the operation commenced shortly

before noon when Troop A moved with the infantry to search the village. After

a bitter all-day battle, the mounted units and the infantry succeeded in clearing

the village and securing the northern perimeter of the air base.2

-

- Battle of Long Binh and Bien Hoa Area

-

- The cavalry battles on the northwestern side of Saigon blunted one of two

major attacks toward the capital. The enemy made his other effort in the Long

Binh-Bien Hoa area, twenty-two kilometers northeast of Saigon. This huge,

sprawling, logistical and command complex had been carved out of a rubber

plantation early in the war. It contained II Field Force headquarters; III

Corps South Vietnamese Army headquarters; the U.S. Military Assistance Command,

Vietnam, III Corps advisory headquarters; U.S. Army, Vietnam, headquarters;

Bien Hoa Air Base; and the mammoth Long Binh Logistics Depot. (Map 12)

-

- On the night of 30 January, the 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized),

commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John B. Tower, moved to Long Binh as a reaction

force for the 199th Light Infantry Brigade. The battalion dispersed by companies

to screen for possible Viet Cong and North Vietnamese infiltrators. The battalion

was also instructed to be prepared to reinforce critical command, control,

and logistical installations in the giant complex.

-

- At 0100 on 31 January, at the same time Tan Son Nhut was attacked, a well-coordinated

assault was launched against the Long Binh-Bien Hoa complex from all points

of the compass. At least four Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Army battalions

were in-

- [123]

- volved, and for a time the command post of the mechanized battalion was

flooded with reports of enemy action. All elements were placed on alert and

at 0445, the battalion was ordered to reinforce the Long Binh ammunition depot,

the III Corps South Vietnamese Army headquarters, and the III Corps prisoner

of war compound.

-

- Company B, minus one rifle platoon, arrived at the ammunition dump at 0630

and, after coordinating with the defenders, moved into the area. The company

was greeted by sniper fire, which knocked several infantrymen off their vehicles

and diverted attention from the Viet Cong who were placing satchel charges

in and around the ammunition bunkers. Despite the knowledge that they were

operating in the midst of tons of explosives, men of the 2d Battalion, 47th

Infantry (Mechanized) , ran from bunker to bunker retrieving explosive charges,

as other troops sought out and killed the snipers and sappers. At 0750 several

bunkers in the storage area blew up and Company B suffered four casualties.

The remainder of the day the company continued working through the area, clearing

bunkers and forcing the enemy to withdraw. The II Field Force ordered Company

B to remain in the ammunition dump as a security force, despite Colonel Tower's

plea that they be used elsewhere.

-

- Carrying out the battalion's second mission, Company C, 2d Battalion, 47th

Infantry, arrived at 0554 at the III Corps South Vietnamese Army headquarters,

which was under heavy enemy assault. Attacking from march column, Company

C crashed into the flank of the Viet Cong forces, pinning them down with machine

gun fire while the infantry dismounted and overran the position. The final

assault required house-to-house fighting before the enemy was defeated. With

the headquarters compound secure, at the cost of eight men wounded and one

APC lost, the company moved to the prisoner compound east of Bien Hoa City.

Again meeting strong resistance and fighting from house to house, the dismounted

troopers finally overran the enemy positions in the late afternoon with a

savage attack supported by the mounted machine guns. At 1730 the Viet Cong

withdrew and Company C returned to the South Vietnamese corps headquarters,

where it maintained security throughout the night.

-

- With two companies fighting the enemy in widely separated locations, the

2d Battalion, 47th Infantry, was given a third mission -to reinforce a unit

of the 199th Light Infantry Brigade near the village of Ho Nai on National

Highway 1. Company A and the battalion headquarters moved north to link up

with the infantry. The enemy attack was seriously threatening installations

to the

- [124]

- TANK AND M113 DURING ENEMY ATTACK ON BIEN HOA, Tet 1968

-

- east of Bien Hoa, and to relieve this pressure the mechanized infantry of

Company A joined elements of the 4th Battalion, 12th Infantry, and 2d Battalion,

3d Infantry, in an attack north of Highway 1. The final successful assault

was preceded by gunship and artillery fire and aided by machine guns from

the APC's that forced the enemy from hastily dug foxholes. When the smoke

and dust settled, bodies of forty-two of the Viet Cong were found, along with

assorted weapons and equipment. At dark Company A, 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry,

moved to a night position near the post of Long Binh.

-

- The second act in the battle for Long Binh and Bien Hoa had begun while

the 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry, was fighting its widely separated battles.

Early on the morning of 31 January, Troop A, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, was

acting as a security force for an artillery unit at Fire Support Base Apple,

twenty-eight kilometers east of Bien Hoa on National Highway 1. At 0100 the

troop, commanded by Captain Ralph B. Garretson, was alerted to move. At 0230

Captain Garretson was directed to leave a platoon at the fire base and move

the remainder of his troop toward Bien Hoa; he was to receive further instructions

while he was en route. Troop A moved immediately, leaving the 3d Platoon to

furnish security for the artillery.

-

- There were early indications of things to come as the troop entered the

town of Trang Bom on Highway 1 and ran into a company-size ambush. The fight

lasted only five minutes as the troop, still moving, concentrated its fire

along the roadside and

- [125]

- rode through the ambush. The troopers, receiving sporadic fire along the

way, reached a concrete bridge eighteen kilometers east of Bien Hoa. After

the first tank crossed the bridge, a thunderous explosion dropped the span

into the stream. The ACAV's had no trouble fording the stream, but with the

exception of the one that had already crossed the tanks had to be left at

the bridge.

-

- Now out of radio contact with both the squadron headquarters and Bien Hoa,

the troop continued on to the city to find the square filled with two companies

of Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers. The 1st Platoon charged through

the enemy not realizing who they were. By the time Captain Garretson arrived,

however, the enemy force had dispersed and opened fire, disabling two ACAV's.

The 2d Platoon pushed aside the disabled vehicles and entered the square in

a hail of machine gun fire. After this brief action the small cavalry force

consisted of one tank and eight ACAV's.

-

- Continuing to move, the troop was joined by the squadron commander, Lieutenant

Colonel Hugh J. Bartley, who directed Captain Garretson to Bien Hoa Air Base.

As he flew over the troop, Colonel Bartley spotted an enemy ambush just outside

the base, with several hundred Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops in the

ditches near the southeast entrance. The men quickly moved off the road some

thirty to forty meters behind the ambush, firing as they went, and destroying

the enemy force on one side of the road.

-

- After entering the base, the cavalry force was attached to a battalion of

the 101st Airborne Division, which was attempting to reduce the enemy forces

on the base perimeter. The cavalrymen were split between two companies of

infantry attacking a position at the southeast corner of the air base. The

battle lasted most of the day, culminating in a breakout attempt by the enemy

that was stopped short by the cavalry troop. In this fight the 2d Platoon

lost two ACAV's; the one tank lost two crews and took nineteen hits from rocket

grenades but was still operational. For the rest of the day the troop was

the reaction force for the air base defense. The next morning Troop A returned

to Fire Support Base Apple; it had suffered five killed and twenty-three wounded.

-

- The final curtain was rung down on the Long Binh-Bien Hoa battle by the

11th Armored Cavalry Regiment on 1 February. Although the regiment was conducting

operations in the thick jungles of War Zone C, on the morning of 31 January

the entire unit pulled out, consolidated, and moved over 103 kilometers to

Bien Hoa, all in eight hours. The regiment had completely circled

- [126]

- the Long Binh-Bien Hoa complex by 2100 that night. The next day U.S. airborne

infantry and the 3d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, swept through

Bien Hoa and cleared the town. For the rest of the month the 11th Armored

Cavalry remained in the Long Binh-Bien Hoa and Saigon areas.

-

- Battles in Vinh Long Province

-

- The Tet battles in the IV Corps Tactical Zone were characterized

by the same intensity as those in other tactical zones, but in most cases

they involved South Vietnamese Army units. In the provincial capital of My

Tho, South Vietnamese cavalry forces along with U.S. and South Vietnamese

infantry engaged in a bloody three-day battle in which over 800 enemy troops

were killed. Farther south Vietnamese Army cavalrymen were ordered on one

hour's notice to fight their way along the fifteen kilometers from their base

camp to the city of Phu Vinh (Tra Vinh). Using massive firepower and without

the aid of supporting infantry, they destroyed the enemy resistance in the

city in less than twenty-four hours.

-

- The Tet offensive in Vinh Long Province started at 0300 on 31 January

when the Viet Cong attacked Vinh Long City and the compounds of South Vietnamese

cavalry units, ninety-five kilometers southwest of Saigon in the delta. The

3d Squadron, 2d Armored Cavalry Regiment, swiftly secured its own compound

and dispatched elements to assist the headquarters of the 2d Armored Cavalry

Regiment, which was under attack. The 3d Squadron forces crashed through the

enemy force around the headquarters perimeter, then attacked and routed the

Viet Cong.

-

- The squadron was then ordered to assist in the defense of Vinh Long Airfield,

while regimental headquarters troops were to provide security for the southwestern

portion of the city perimeter. After clearing the outer perimeter of the airfield,

the 3d Squadron was ordered back into the city where it cleared the route

from the airfield to the tactical operations center in the middle of the town.

When the cavalry started to clear Vinh Long's main street, heavy automatic

weapon and rocket propelled grenade fire from buildings stalled the mounted

attack. Finally, the 3d Squadron linked up with a company of the 43d Ranger

Battalion of the South Vietnamese Army, but in the face of intense fire the

Rangers retreated, leaving the 3d Squadron to continue the assault on its

own.

-

- A Regional Forces company was sent to fight with the squadron, but it too

refused to advance. After a direct order by the cavalry commander, the Regional

Forces company reluctantly fol-

- [127]

- lowed the ACAV's, but the attack bogged down. As evening came, the company

departed and the 3d Squadron pulled back to protect secured areas of the city.

-

- Early the next morning the squadron again attempted to clear the main street,

still without infantry support. The fighting seesawed back and forth all day

through the rubble, but little progress was made. Every move toward the main

street had to be fought from house to house. Even when the squadron was reinforced

by fighting elements of the regimental headquarters, the most that could be

achieved was security of the tactical operations center and the provincial

administrative center, and even that was a constant battle.

-

- During the night of 1 February, South Vietnamese soldiers from the 3d Battalion,

15th Infantry, arrived by boat, and the next morning the 3d Squadron, 2d Armored

Cavalry Regiment, and the infantry began clearing the main street. For the

fourth consecutive day there was heavy fighting. With U.S. helicopter gunship

support, and after five full days of frustration, the combined forces charged

the Viet Cong positions and broke through. The cavalry troopers and a Ranger

company quickly cleared the western section of the city and the remaining

Viet Cong fled.

-

- In five days of intense fighting South Vietnamese Army cavalrymen had adapted

themselves to urban combat; in the beginning they did not even have the aid

of supporting infantry. The courage and tenacity of individuals and the ability

of the unit to bring firepower to bear in critical areas kept the Viet Cong

off balance and finally enabled the cavalrymen to seize the initiative from

the attackers.

-

- The magnitude of the enemy Tet offensive of 1968 surprised the free world

forces. Despite intelligence reports to the contrary, the enemy was considered

incapable of mounting a countrywide offensive and such an attack was not given

serious military consideration. That the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese could

attack Saigon or seize and hold Hue for twenty-six days was believed impossible.

Those who thought that an attack was coming did not foresee a widespread offensive.

When the attacks came, armored units were sent into almost every significant

action in South Vietnam. Mounted troops became quick reaction forces, attacking

in large cities and destroying enemy units or driving them away. Armored forces

screened the borders, blocking enemy infiltration routes, denied the enemy

access to his objectives, and intercepted units along routes of resupply and

withdrawal. Route security and convoy escort were performed by mounted units

to keep roads open

- [128]

- and insure that convoys reached their destinations. In Tet 1968,

armor paid its way.

-

- Second Offensive

-

- In the period immediately after Tet, free world forces struggled to sort

out units in the resulting confusion. Many, particularly armored units, were

widely spread in defensive missions far from their normal operational areas.

Losses, particularly of equipment, had been heavy, and many units needed time

to replace materiel and train new men. For a time there was a shortage of

M48A3 tanks, made up for in part by issuing M48AI tanks to selected units.

The hull and guns of the tanks were the same, but the M48AI used gasoline

and its reduced range and susceptibility to fire did not make it very popular.

-

- Intelligence analysts indicated that the enemy was also replacing troop

losses and rebuilding supply caches preparatory to launching another offensive.

Sweep operations disrupted the enemy time schedule for renewed attacks, but

larger enemy units remained hidden in base areas throughout South Vietnam.

Anticipation of renewed enemy activity, particularly around Saigon and the

Capital Military District, resulted in many false warnings with units alerted

for attacks that never came.

-

- To relieve the pressure free world forces attacked, with South Vietnamese

Army units now participating in strength. In early April Operation TOAN THANG

I was launched to drive the enemy units away from Saigon. Highly decentralized,

the operation was characterized by small daylight search missions and night

ambushes involving seventy-nine battalions in III Corps Tactical Zone alone.

Intelligence information gathered in these actions revealed the imminence

of a second enemy offensive. The Tet attack had suffered from poor

coordination among the enemy units because strict security measures were employed.

This time the enemy widely disseminated his plans, enabling the free world

forces during TOAN THANG I to learn of them quickly from captured documents

and prisoners. By late April all invasion and infiltration routes into Saigon

and other key cities were watched and heavily guarded.

-

- This alertness, the large-scale allied operations after Tet, and

heavy enemy losses during Tet weakened the second enemy offensive in early

May, which U.S. forces nicknamed "Mini-Tet." The main enemy effort

was made in the Saigon area, where most of the combat took place. The 1st

Squadron, 4th Cavalry, got into action early when, on 5 May 1968, it discovered

three North Vietnamese soldiers seventeen kilometers north of Saigon and triggered

a two-

- [129]

-

M41 OF SOUTH VIETNAMESE ARMY ADVANCES ON ENEMY POSITIONS

IN SAIGON, MAY 1960

-

- day battle with a North Vietnamese Army battalion. After massive air, artillery,

and air cavalry support and constant mounted attacks by ACAV's and tanks,

the combined arms team routed the enemy. By dark on the 6th, the North Vietnamese

had gone-leaving over 400 dead on the battlefield.

-

- Closer to Saigon, the 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry (Mechanized) , and the

2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized) , again closed with the enemy in

house-to-house fighting near the "Y" bridge on the west edge of

the city.3

The mechanized troops used every means of fire support available in

six days of intense fighting that, curiously, was broken off each night by

the enemy. The final major battle was fought on 10 May by the 5th Battalion,

60th Infantry, and the enemy was driven away from the city for the last time.

Mop-up actions continued for a few days, but the battle for Saigon was over.

- [130]

- After the May offensive failed, the enemy retreated to base camps with the

free world forces in pursuit. Another minor attack was made against Saigon

on 25 May, but the attackers were quickly routed. Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

troops emerged from hiding places to surrender. On 18 June the largest number

of enemy troops surrendered-141 enemy soldiers turned themselves over to the

South Vietnamese Army forces northeast of Saigon. Scattered and diminished

fighting continued till late June. While the fighting was still going on,

peace talks had begun in Paris on 13 May.

-

- The May attacks were but a shadow of the Tet offensive in February,

and had no apparent military objective. It appeared that small groups of enemy

soldiers were dispersed over wide areas in an attempt to make their attacks

appear heavier than they actually were. A number of rocket attacks were also

employed against the capital to create an image of Saigon under seige. The

principal target was Saigon, with attacks in other areas of the country designed

to divert free world forces. It appears probable that the attacks were intended

to influence the peace talks rather than to achieve a military goal.

-

- Third Offensive

-

- After the second enemy offensive, just as after the first, both sides stepped

back to assess the result and repair the damages to men and equipment. For

the free world forces this interim was unlike the previous one because an

air of confidence and optimism prevailed. The recuperative means of the free

world forces were greater than those of the enemy. No longer content to sit

and wait for the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese to attack the populated areas,

units went into the bush with a vengeance. Base areas were penetrated repeatedly.

Thus the third and last enemy offensive during 1968 fell not on the population

or on critical areas but directly on the free world combat units, who were

well prepared.4

-

- Recognizing the change in the free world military position, the enemy chose

objectives that differed in two ways from those of earlier offenses. First,

the offensive had limited goals. Second, the attacks were directed against

U.S. troops, base camps, and equipment rather than at Vietnamese population

centers. Intelligence after the attack revealed that a prime objective was

to inflict heavy

- [131]

- losses on U.S. troops in hope of winning a political and psychological victory.

-

- The most sustained fighting of this third offensive took place in the III

Corps Tactical Zone in Tay Ninh Province. By August 16,000 soldiers of the

5th and 9th Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Divisions had infiltrated into

War Zone C, prepared to attack. The 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, the

largest free world force in the area, included the 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry

(Mechanized) ; 4th Battalion, 23d Infantry (Mechanized) ; 3d Battalion, 22d

Infantry; 2d Battalion, 34th Armor (-) ; and the 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry.

Relying on the mobility of its armored units, the brigade was organized into

combined arms task forces with attached tank, infantry, and mechanized infantry

units heavily supported by artillery. From the fire bases around Tay Ninh

City task forces sent out wide-ranging patrols to prevent or break up enemy

movement.

-

- For ten hectic days and nights beginning 17 August 1968, the 1st Brigade

fought the enemy over an area of 1,500 square kilometers in the unfavorable

summer wet weather. The fight started when the enemy made a night attack on

a fire support base six kilometers north of Tay Ninh, using human wave tactics;

the attackers were stopped short of the defensive wire by the overwhelming

firepower of tanks, aircraft, artillery, and infantry. By daylight a heavy

attack on Tay Ninh City was under way, but at the end of the day the enemy

had been beaten back by two armored task forces and a cavalry troop. The enemy

then shifted thirty kilometers to the east into some rubber plantations in

the hope of bypassing the brigade and striking farther south. But the mobile

task forces followed, and for nine days fighting ranged through the rows of

rubber trees. Counterattack followed attack with such regularity that it became

difficult to tell which was which. The only certainty was that the brigade

was keeping the pressure on. Movement and firepower were the keys, aided in

strong measure by the unity of command within the brigade.

-

- In almost every fight, and they took place every day and every night, the

enemy was severely beaten. There were exceptions. On 21 August a mechanized

infantry company took on two North Vietnamese battalions and for more than

an hour held its own. After suffering heavy losses and with one officer left

alive, the company was forced to withdraw under cover of supporting artillery.

Again, on 25 August a logistical convoy of eighty-eight vehicles was ambushed

south of Tay Ninh. An armored force moved in and severely punished the enemy,

but not before the convoy had lost many men and vehicles. In these actions

the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese prevailed by weight of numbers.

- [132]

-

M113 IN ACTION AT BEN CUI RUBBER PLANTATION, AUGUST 1968.

Hollow steel planking on sides of vehicle offer protection against shaped

charges.

-

- By 27 August the third enemy offensive in War Zone C had ended in defeat

for enemy units. It was largely the mobility and firepower of the 1st Brigade

combined arms teams that made victory possible for the smaller American forces.

The ability of U.S. forces to maneuver and mass rapidly to defeat a strong

but slower enemy was the critical factor. The attacks were the last in the

III Corps Tactical Zone. For the remainder of the year and well into the next

the enemy stayed in Cambodia refitting badly beaten units.

-

- The third enemy offensive, however, was not limited to the III Corps area.

In I Corps far to the north the American 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry, 23d Infantry

Division, blocked the path of three regiments of the 2d North Vietnamese Army

Division that intended to attack Tam Ky City. The squadron had previously

fought insignificant battles west of the city, and consequently was maintaining

protective security around Tam Ky by means of daily reconnaissance in force.

It was a platoon in one of these sweeps, operating with a troop of South Vietnamese

cavalry, that started the fighting in one of the hardest battles the 1st Squadron,,

1st Cavalry fought against the North Vietnamese.

-

- On the morning of 24 August 1968, Lieutenant Thomas Guiz,

- [133]

- leader of 2d Platoon, Troop A, 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry, was operating

west of Tam Ky with a South Vietnamese troop from the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry.

At 0925 the South Vietnamese cavalry received intense fire from a clump of

trees on high ground surrounded by rice paddies. In the first few seconds,

one APC was hit several times by recoilless rifle fire and exploded in flames.

The Vietnamese cavalry, calling for reinforcement from the 2d Platoon, fired

into the enemy position.

-

- Lieutenant Guiz and his platoon responded, but so heavy was the enemy fire

that it took two air strikes and air cavalry support before the platoon could

maneuver abreast of the Vietnamese cavalry troop. When the air strikes lifted,

the combined forces then assaulted the hill in a line formation. Several vehicles

were hit by recoilless rifle fire and the attack stalled. The enemy force

was too strong to be pushed off the hill by frontal assault so the cavalrymen

withdrew and awaited reinforcements from the 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry. Lieutenant

Colonel Raymond D. Lawrence, commanding the 1st Squadron, ordered Troop C

and the remainder of Troop A into the battle. The enlarged cavalry forces

probed the area with automatic weapons fire and tried to encircle the high

ground, but were driven away by heavy fire from antitank weapons. Unable to

close with the enemy, the cavalrymen dismounted and continued the attack on

foot, but even after savage bunker-to-bunker fighting little ground was gained.

-

- Throughout the afternoon Colonel Lawrence had repeatedly requested a company

of infantry to assist his cavalrymen in the fight. At 1630 an infantry company

became available to make a combat assault if a secure landing zone could be

provided. A landing zone 2,000 meters away was selected, but when Troop C

moved toward it, the men ran into the heaviest fighting of the day. "We

had to cross a small forest to get to the LZ," stated Private First Class

Mark Bellis, "and as soon as we were in the middle, we were right up

ambush alley." The attack came from all sides and the cavalrymen formed

their vehicles in a circle to fire in all directions. Again and again, the

North Vietnamese infantry rushed the circle only to be stopped by the heavy

fire. As darkness approached, Colonel Lawrence realized that the landing zone

could not be secured, and the airmobile infantry, now two companies, were

therefore sent to Hawk Hill, base camp of the 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry. Both

companies readied themselves for anticipated fighting in the morning.

-

- Troop C fought its way out of the small forest area back to its original

position, and there joined Troop A after dark. Although supplies were now

critically needed by all units, the policy of the

- [134]

- 23d Infantry Division did not permit resupply by CH-47 helicopter if hostile

fire was being received by a ground unit. The cavalrymen, therefore, were

forced to break away from the enemy to secure a landing zone. The two troops

then set up a single position near the battlefield to await resupply. The

South Vietnamese 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, withdrew to Tam Ky to defend the

city. Fighting on 24 August had been fierce, with over 200 North Vietnamese

killed, but the enemy was still present and in strength.

-

- Colonel Lawrence's plan was to place an additional cavalry troop, Troop

B, in a blocking position, and to attack with the other two cavalry troops,

reinforced with infantry, which would arrive at first light. At 0615 while

en route to the blocking position, Troop B came under attack from a North

Vietnamese force. The cavalrymen, quickly gaining fire superiority, left one

platoon to deal with the enemy as the other two platoons drove on. Reaching

the proposed blocking position, the cavalrymen found themselves in the middle

of a North Vietnamese regimental headquarters. They drove their vehicles through

the position, firing in every direction, but enemy fire was so intense that

they were finally forced to regroup and form a circle. As on the previous

day, the North Vietnamese tried to overrun the vehicles but were repulsed.

Although surrounded, the troop had disrupted the enemy command and control

facilities.

-

- While Troop B's battle raged, Troops A and C started to advance toward their

assigned positions. Almost as soon as it left the night camp, Troop A came

under heavy rocket grenade and recoilless rifle fire. Ground gained in this

sector was measured in meters, as infantry and cavalry unsuccessfully battled

the enemy for the high ground. Troop C, which met little resistance at first,

was stalled when its attached infantry was pinned down by heavy small arms

fire. Thick undergrowth and rough terrain slowed the cavalry attempt to help

the infantry, but after an all-day battle both cavalry and infantry managed

to pull back. With darkness approaching, once again the resupply needs of

the armored force and the division policy regarding CH-47 helicopters forced

the cavalry to disengage. In positions near the battlefield, the U.S. forces

resupplied and readied themselves for more fighting. The day had been expensive

for the North Vietnamese, who lost 250 killed.

-

- The plan for 26 August called for the entire force to shift southwest, then

attack north with all three cavalry troops and the attached infantry. If the

North Vietnamese were still in their trenches, the flanking attack was designed

to surprise them. Following a twenty-minute artillery preparation, the squadron

and its infantry attachments attacked the enemy right flank; resistance was

- [135]

- light-the enemy had left a few rear guard troops and withdrawn from the

battlefield. During the daylong scattered fighting that followed, Team B captured

two North Vietnamese soldiers who related that over 400 of their troops had

fled to the northwest the previous night. Logistical needs once again outweighed

tactical needs, and the squadron halted to resupply.

-

- Colonel Lawrence sent three teams to the northwest on 27 August. Troop F

(Air), 8th Cavalry, screening to the front, reported the presence of a North

Vietnamese antiaircraft unit. A prisoner later related that the North Vietnamese

unit had one rocket propelled grenade crew attached, and that the opening

round was to be the signal for everyone to open fire. Team A, deployed on

line, laid down a base of fire, and advanced on the enemy at full speed. The

rocket grenadier took aim at the lead American vehicle and pulled the trigger-misfire!

With no signal given, the North Vietnamese unit panicked. "We just drove

right in," stated Lieutenant Guiz. "We captured two caliber .51

antiaircraft machine guns and found a lot of enemy packs. The team killed

or captured all but three men in the unit."

-

- The enemy force, estimated to number around 1,300 men before the start of

the battle, had had enough, and in the darkness that followed the North Vietnamese

melted back into the hills. The successful cavalry sweep operations had intercepted

the enemy movement toward Tam Ky, and forced a fight before the North Vietnamese

were able to reach their objectives. Armored firepower and air and artillery

support had inflicted crippling losses and had stopped this part of the enemy

third offensive as it began.

-

- Aftermath

-

- In the wake of these enemy offensives, the free world forces found themselves

in control of the battlefields. For armored units the offensives, particularly

Tet, had brought a demonstration of everything that armor proponents had claimed.

The ability of armored units to move fast with overwhelming firepower had

been of the utmost importance throughout the offensive.

-

- Armored units in combined arms task forces would now spend most of their

time in the bush pursuing the weakened Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. A new

American armored unit, a mechanized brigade, was being sent to Vietnam. The

South Vietnamese armored force was forming seven more cavalry regiments.5

Even

- [136]

- more important, in the redeployment planning that was soon to begin, armored

units, both air and ground, were scheduled as last to leave Vietnam because

they provided mobility and firepower at far less cost in manpower than any

other type of unit. It had taken a long time to convince the Army, but there

was no longer any doubt about the utility of armored forces in Vietnam's counterinsurgency

and jungle warfare. The three offensives brought about a real change in the

acceptance of armored units and ended the long ambivalence toward armor in

Vietnam.

-

- The campaigns of 1968-Tet, and the second and third enemy offensives-were

the last concerted enemy offensives against the combined free world forces

in Vietnam. In a period of seven months, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

forces were severely defeated; over 60,000 enemy soldiers lost their lives

without making any tangible gains on the ground. The free world forces struck

back both during and after this campaign with a strength that carried the

battle to the borders of South Vietnam and beyond. The soldiers of the Republic

of Vietnam gained new confidence in the very battles that were designed to

persuade them to desert to the enemy.6

- [137]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-