- Chapter VI:

-

- The Fight for the Borders

-

- Changing Strategy

-

- In the aftermath of the 1968 enemy offensives both sides changed strategy.

For the North Vietnamese, the change was a necessity brought on by heavy losses

in men, equipment, and supplies. With the Viet Cong underground organization

exposed or destroyed in many areas, main force units short of men, equipment,

and leaders, and the logistical system drained of supplies, the enemy had

no choice but to retire to sanctuaries. On the free world side, U.S. troop

strength, despite some losses, reached a new high of nearly 550,000 in April

1969, and the South Vietnamese Army gained confidence from new weapons and

freedom of action. It was the time, therefore, to pursue the enemy into his

sanctuaries and keep up an unrelieved pressure that would prevent his returning.

-

- The new strategy of the free world forces was applied under the leadership

of General Creighton W. Abrams, who succeeded General Westmoreland as Commander,

U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in the summer of 1968. By background

and training General Abrams was the man for the job. One of the great commanders

of small armored units in World War II, he subsequently commanded an armored

division and a corps, and served as Vice Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.

For a year before he assumed command he was General Westmoreland's deputy,

and concentrated his attention on the Vietnamese Army. His rapport with South

Vietnamese leaders was excellent, his confidence in the South Vietnamese Army

was a great boost to Vietnamese morale, and his conviction that the South

Vietnamese were capable of a much broader participation in the war than had

been allowed them in the past augured well for the new strategy.

-

- When the enemy forces fled from the battlefields, they regrouped in base

areas inside South Vietnam. With virtually no large Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

units in the field, free world forces began to engage in continual small unit

actions to locate and defeat the remaining enemy forces. Increased American

strength and the growing strength of the South Vietnamese Army also allowed

free world forces to penetrate and destroy the enemy base system in South

Vietnam. As the tempo of these operations increased, the enemy fled once again-this

time to sanctuaries in Laos and Cam-

- [138]

- bodia where refitting, resupplying, and training could. be carried out without

interference.

-

- By mid-1969 the enemy was operating from these sanctuaries, venturing occasionally

into South Vietnam as logistics permitted. These forays, known as high points,

were preceded by enemy logistical buildups of enough supplies to support the

high points. The enemy tactic of sticking out a so-called logistics nose,

followed by troops who were supported by the buildup, became a familiar one.

In 1969 and 1970 the free world countertactic was to cut off the logistics

nose when possible and thus frustrate the enemy attack that was intended to

follow.1

-

- American and South Vietnamese armored forces in the air and on the ground

played an important role in the fight to prevent a logistical buildup and

to seal the borders of South Vietnam, Their mobility and heavy firepower enabled

them to operate in small groups with less chance that any single unit would

be overwhelmed. This mobility also enabled them to disperse over wide areas,

yet mass quickly when the enemy struck.

-

- Armored Forces Along the Demilitarized Zone

-

- In mid-1968 the last major U.S. tactical unit that was to be sent to Vietnam,

the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized), was arriving from Fort

Carson. By 1 August 1968 the five combat units of the brigade were in Vietnam:

the 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry (Mechanized) ; the 1st Battalion, 77th Armor;

the 1st Battalion, 11th Infantry; the 5th Battalion, 4th Artillery (155-mm.,

self-propelled); and Troop A, 4th Squadron, 12th Cavalry. Within a few days

they started combat operations in the I Corps Tactical Zone, immediately south

of the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam.

-

- The North Vietnamese Army units along the Demilitarized Zone were unaccustomed

to fighting U.S. armored forces. The U.S. Marines operated in this region,

but used their armor in small groups whose primary role was support of dismounted

infantry. Thus, the 1st Brigade enjoyed some immediate success against enemy

troops who tried to stand and fight, believing themselves to be facing tank-supported

infantry as before. These encounters were usually one-sided, with the North

Vietnamese losing significantly in men and equipment. However, the enemy quickly

learned the futility of a stand-up fight against the consolidated mechanized

- [139]

- force of the brigade, and changed his tactics to avoid the mounted formations.

-

- Emphasizing offensive action away from fixed bases, the 1st Brigade attacked

the enemy whenever and wherever he could be found. After only two months of

combat the brigade received a letter of congratulations from General Westmoreland,

newly appointed Army Chief of Staff, who wrote that the unit's actions had

"demonstrated the Brigade's readiness to take its place with other veteran

units in Vietnam."

-

- By late 1968 1st Brigade operations in the I Corps area were fairly illustrative

of small unit actions throughout the country. The brigade concentrated on

rooting out the Viet Cong underground organization and breaking up guerrilla

units by sending battalions into areas whose limits corresponded with local

Vietnamese district boundaries. Liaison officers from the American battalions

were assigned to each district and direct communications were established

between battalion and district. A close association was thus developed between

Vietnamese Regional and Popular Forces and U.S. battalions. Perhaps most important

of all, the brigade began to develop a network of village agents that was

to prove invaluable in providing timely information about the Viet Cong organization.

-

- Mechanized infantry was particularly successful in ferreting out the Viet

Cong. Mechanized companies could move rapidly through search areas and quickly

cordon off a village suspected of harboring Viet Cong. Local Vietnamese forces

operating with the American troops usually conducted the detailed search.

When it was over the mechanized company would move on, sometimes many miles,

to place a cordon around another village.

-

- As these operations became more successful local government improved and

Viet Cong village organizations collapsed. Members of the Viet Cong could

no longer safely submerge in village populations, and when they fled to the

countryside they were hounded by American infantry and artillery. Although

it was certainly not the efforts of the mounted infantry alone that drove

the Viet Cong from the villages, the mechanized troopers performed a task

that neither police, local militia, nor standard U.S. infantry could accomplish

alone. One Vietnamese district chief said: "On a good day, the U.S. mechanized

infantry may not always get here quite as fast as airmobile infantry-but they

stay with us longer and with more firepower."

-

- After the early encounters, combat in the 1st Brigade's area of operation

was light. Since lack of vegetation made the M 113 visible for hundreds of

yards, particularly on a moonlit night, it was a

- [140]

-

PREPARING NIGHT DEFENSIVE POSITIONS ALONG THE DEMILITARIZED

ZONE. Men of 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry, dig foxholes but vehicles

are left in the open to allow maneuver.

-

- simple matter for the enemy to bypass the vehicles. The brigade countered

this tactic by saturating an area with four-man patrols. Each mechanized infantry

company was required to have a minimum of twenty ambush patrols of four men

each night. Commanders briefed their troops at the noon meal; patrols then

mounted. armored personnel carriers and were taken on a ground reconnaissance

of each position. At dusk, while they were still visible to enemy in the area,

the M113's were again dispatched on designated reconnaissance routes. Immediately

after dark, while the APC's were moving, each four-man patrol dismounted and

established its ambush position. This technique made it difficult for an observing

enemy to detect ambush positions because the vehicles never stopped moving

during the reconnaissance.

-

- After the patrols were in place, the M 113's formed platoon night defensive

positions and prepared to move to the assistance of any patrol that ambushed

an enemy force. Because ambush patrols were close together, usually separated

by a rice paddy or a dike, the enemy could not bypass all of them. Establishing

four-man patrols was a calculated risk since they had little staying power,

but once the patrols had engaged the enemy, reinforcements moved according

to plan. Upon hearing the first round fired, the vehicles nearest the ambush

took the most direct route to the fight, with headlights blazing. Later, a

tabulation of all fights during the use of this technique showed that the

longest time lapse, from the first round fired to the arrival of the armored

cavalry assault vehicles, was less than four minutes. It was the speed of

the M113 that permitted the American forces to take the risk of setting up

four-man patrols.

- [141]

- SHERIDAN M551 AND CREW MEMBERS OF THE 3D SQUADRON, 4TH CAVALRY

-

- The Sheridan

-

- In early 1969 the U.S. Army introduced a new combat vehicle into its armored

forces in Vietnam-the General Sheridan M551. Cavalry commanders in Vietnam

had long expressed a need for an amphibious tracked vehicle with more firepower

than the armored cavalry assault vehicle but with the same mobility.2

The Sheridan was a partial answer; it was to replace M48 tanks in

cavalry platoons of divisional cavalry squadrons and ACAV's that had been

substituted for tanks in cavalry platoons of regimental cavalry squadrons.

The regimental squadrons of the 11th Armored Cavalry retained their M48A3

tanks in the squadron tank companies.

-

- Designed as an antitank weapon for airborne forces, the Sheridan was sent

to Vietnam without its primary antitank missile equipment aboard. Its armament

consisted of a 152-mm. main gun, firing combustible-case ammunition with several

different warheads, a .50-caliber M2 machine gun at the commander's station,

and a 7.62-mm. machine gun mounted with the main gun. The Sheridan had a spotty

development history, characterized by difficulties with

- [142]

- the complex electronics gear associated with its antitank missile system

and problems with the combustible cases for its main gun rounds. The missile

system was not a problem in Vietnam-it was not used-but the combustible case

gave persistent trouble.

-

- As early as 1966 the Army staff in Washington was pressing the U.S. Army,

Vietnam, to accept the Sheridan for its cavalry units. At that time the U.S.

commander in Vietnam demurred on the grounds that since no main gun ammunition

was available the vehicle was no more than a $300,000 machine gun platform,

not as powerful and agile as the M113. When main gun ammunition was finally

available in 1968, however, plans to equip two divisional cavalry squadrons,

the 1st and 3d Squadrons of the 4th Cavalry, were approved. Neither squadron

wanted the Sheridan because it was suspected of being highly vulnerable to

mines and rocket propelled grenades and could not break through jungle like

the M48A3. General Abrams, during a visit to the 11th Armored Cavalry in late

1968, mentioned this fact to the regimental commander, Colonel George S. Patton.

Colonel Patton suggested that the vehicle would receive a better test if the

Sheridans went to a divisional squadron and a regimental squadron. General

Abrams agreed, and sent the first Sheridans to the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

and the 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry.

-

- Both units started training in January 1969. The new vehicles were accompanied

by factory representatives, instructors, and evaluators to assist in the training.

Reactions of the two units to the Sheridans were quite dissimilar, and in

large part affected their approach to training. The 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

had elected not to stand down an entire troop for transition; as a result

key leaders were often absent from briefings and training. The 11th Armored

Cavalry, on the other hand, gave an entire troop seven days of uninterrupted

training. In addition, in the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, the Sheridan replaced

the M48 tank in cavalry platoons one for one, while in the 11th Armored Cavalry

three Sheridans replaced two cavalry platoon armored cavalry assault vehicles.

Thus, one unit exchanged a somewhat less capable armored vehicle for its M48

tank, while the other unit exchanged two lightly armed and armored cavalry

assault vehicles for three Sheridans-armored vehicles with considerably greater

firepower and armor.

-

- On 15 February 1969, in the first combat action involving a Sheridan, one

from the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, struck a 25pound pressure-detonated mine.

The explosion ruptured the hull and ignited the combustible-case ammunition

of the main gun, causing a deadly second explosion that destroyed the vehicle.

- [143]

- Sheridan crews were uneasy after this catastrophe; they knew that a similar

explosion under an M48A3 tank would simply have blown off a few road wheels.

The feeling that the Sheridan was extremely dangerous began to grow, and,

in the manner of any rumor, spread from unit to unit in Vietnam, and even

reached the training base in the United States.

-

- After the mine incident, the effectiveness of the Sheridan was continually

suspect in the 4th Cavalry. Then, on 10 March 1969, in a night bivouac at

a road injunction east of Tay Ninh City, a Troop A listening post reported

enemy movement and the troop went to full alert. Sheridan crews used night

observation devices to scan the battlefield. Observing a large group of advancing

North Vietnamese, the Sheridans fired canister into the enemy ranks. Confused

by the overwhelming volume of fire, the North Vietnamese broke and ran. The

next morning more than forty enemy dead, including a battalion commander and

a company commander, were found on the battlefield. Reports of this action

quickly spread through the squadron, restoring some measures of confidence

in the Sheridan.

-

- In contrast the 11th Armored Cavalry's first combat with the Sheridan was

successful. In early February 1969, anticipating an enemy offensive, the regiment's

1st Squadron moved to Bien Hoa as a reaction force. Task Force Privette, commanded

by Major William C. Privette, the squadron executive officer, included Troops

A and B of the 1st Squadron. After an enemy mortar and rocket attack on 23

February, Task Force Privette moved out on an armored sweep and immediately

encountered an enemy force. Placing the Sheridans on line, the two cavalry

troops moved forward, firing canister into the enemy ranks. In the face of

this firepower, the Viet Cong panicked and fled, leaving behind over eighty

dead. This fight demonstrated the devasting effect of the 152-mm. canister

round. The troops were impressed with the Sheridan's firepower as compared

with that of the armored cavalry assault vehicle.

-

- By the end of the test period, both units had concluded that the Sheridan

had greater mobility, firepower, range, and night fighting ability than the

vehicle it replaced. On the strength of this conclusion, more Sheridans were

sent to Vietnam, and the total number had increased to more than 200 by late

1970. Eventually almost every cavalry unit in Vietnam was equipped with the

Sheridan, but the fact remained that the Sheridan's combustible-case ammunition

could be detonated by a mine blast or a hit by a rocket propelled grenade.

Consequently, the crew of a Sheridan

- [144]

- abandoned it quickly after a hit; in contrast, the crew of an M48A3 tank

could and did stay and fight after several hits. Another disadvantage was

that during the wet season, when vehicles were drenched every day, the Sheridan's

electrical fire-control system broke down repeatedly.

-

- "Pile-on"

-

- Changing strategy on both sides increased the use of all armored units,

especially armored cavalry. The ability to move men and vehicles rapidly into

battle was ideal for small, widely separated, independent engagements. Cavalry

could move quickly and bring heavy firepower to bear at critical points. Once

the enemy was located and the cavalry unit engaged, reinforcements were immediately

sent in to prevent the enemy from escaping, then maximum firepower was brought

to bear. Rapid reinforcement of a unit in combat was nicknamed "pile-on."

In this period of widespread small actions, some form of pile-on became the

usual mode of operation; it was well illustrated by the action of the 3d Squadron,

5th Cavalry, during the battle of Binh An.

-

- In June 1968 this squadron was performing reconnaissance missions under

operational control of the 1st Cavalry Division in the I Corps Tactical Zone.

During one such mission, Troop C, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, with Troop D,

1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry (Air) -the dismounted ground troop of the air cavalry

squadron of the 1st Cavalry Division-had advanced from the northwest to within

150 meters of the village of Binh An, thirteen kilometers north of Quang Tri

City on the South China Sea. Suddenly, small arms fire and rocket propelled

grenades showered the American forces as several North Vietnamese soldiers

withdrew into the village. Both troops began firing to maintain pressure on

the enemy, while scout sections from Troop C swung to the north and south

of the village to cut off the escape routes. Hundreds of civilians fled from

the village as Lieutenant Colonel Hugh J. Bartley ordered Troops A and B to

reinforce the attacking units and start the pile-on. Shortly, thereafter,

a captured North Vietnamese soldier reported that the 300-man K14 Battalion

of the 812th North Vietnamese Regiment was dug in at Binh An. Realizing that

he now had an enemy battalion with its back to the sea, Colonel Bartley acted

quickly. Troop B was ordered to positions north of Binh An. Troop C moved

into the center of a horseshoe-shaped cordon along with Troop D, 1st Squadron,

9th Cavalry. By 1030 the four cavalry troops were in position around Binh

An. The South China Sea blocked the enemy's escape east, and a Navy Swift

boat, a small

- [145]

-

PILE-ON OPERATION IN I CORPS, JUNE 1968. ACAV's and

tanks of Troop B, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, attack Binh An.

-

- coastal patrol craft, was also summoned to seal the seaward escape routes.

-

- Colonel Bartley's requests for fire support brought tactical aircraft, aerial

rocket artillery, and 105-mm. artillery. The cruiser Boston and destroyers

O'Brien and Edson took station offshore. When Colonel Bartley

gave the order to open fire, the area inside the cordon erupted as hundreds

of shells crashed in on the target. A naval observer reported the shelling

to be so fierce that North Vietnamese soldiers could be seen diving into the

sea to escape.

-

- In order to strengthen the cordon and complete the pile-on, Colonel Bartley

requested the airlift of two infantry companies from the 1st Cavalry Division.

The two companies arrived early in the afternoon: Company C, 1st Battalion,

5th Cavalry, reinforced Troop B on the north side, while Company C of the

2d Battalion joined Troop A on the south. The supporting fire continued for

the rest of the afternoon, and was lifted only long enough for a psychological

operations team to fly over Binh An, urging soldiers to surrender. There was

no response, and the shelling was resumed.

-

- To prevent the North Vietnamese from escaping by night, the enemy command

structure had to be broken up. Colonel Bartley ordered Troops C and D to attack

toward the sea. The cavalrymen assaulted the village but were stopped short

by an impassable drainage ditch, covered by enemy fire. Troop B, with its

attached infantry dispersed between the tracked vehicles, then moved out on

line to attack the village from the north. To allow Troop B to

- [146]

- use all weapons to its front, Troop A soldiers on the south side of the

cordon climbed inside their armored vehicles. Troop B swept forward until

its fire began to ricochet off the Troop A vehicles, then turned around and

fought its way back to its original blocking positions. Colonel Bartley then

called for resumption of supporting fire.

-

- The attack of Troop B apparently ended any intention the enemy had of a

mass breakout through the cordon. Thereafter, only small groups or individuals

tried to escape by sea; tank searchlights illuminated the beaches, exposing

the fugitives. Along the inland sides of the cordon, troops using night vision

devices between flares occasionally spotted North Vietnamese groping through

the dark. Small arms fire stopped them or drove them back. Artillery rounds

continued to explode in the village all night.

-

- Morning brought an increase in the shelling, and when the fire was lifted

the entire cordon tightened toward the center of Binh An. A short time later

the final attack by Troop B was met by no more than scattered enemy resistance.

Stunned North Vietnamese soldiers with hands held high began to stumble from

the wreckage toward the American forces. As the search of the village progressed,

it became apparent that the K14 Battalion had been eliminated. Over 200 bodies

were found and 44 prisoners were taken. Among the dead were the battalion

commander, his staff, all the company commanders, and the regimental S-1.

Three American soldiers had been killed. The executive officer of the 3d Squadron,

5th Cavalry, Major Michael D. Mahler, writing several years later of the fight

at Binh An, stated:

-

- We had once more stumbled into a situation and been able to turn it to our

advantage. But it was more than stumbling and it was not luck that brought

success. It was soldiers in hot steel vehicles out in the glaring sand looking

and poking until the enemy, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, never knew when

or where an armored column would crop up next.

-

- Rome Plows

-

- Not every armored operation carried with it the excitment and clear victory

of a well-executed pile-on. Many, such as maintaining route and convoy security,

for example, involved only occasional meetings with the enemy, but were hard

work and were often boring. One operation that almost every armored unit participated

in at one time or another was the protection of engineer units clearing large

areas of jungle with heavy Rome plows. Usually such operations extended over

a considerable time and involved as many as fifty or more plows. First tried

in the III

- [147]

- ROME PLOWS WITH SECURITY GUARD OF M113's

-

- Corps Tactical Zone, Rome plows soon became commonplace in the two corps

zones to the north, although they were not useful in the delta. Some jungle

clearing was done during operations such as CEDAR FALLS and JUNCTION CITY;

however, major land-clearing efforts did not begin until the arrival of the

169th Engineer Battalion in May 1967.

-

- The task of protecting the clearing operations created a need for techniques

for which there were no precedents. One method was developed during the summer

of 1967 by the 4th Battalion, 23d Infantry (Mechanized), which cleared the

Iron Triangle in III Corps, an area of thick undergrowth and trees of small

to medium size. Daily operations were carried out by three land clearing teams,

each composed of eight Rome plows and two conventional bulldozers, a security

force, and a combined arms force for search and reaction missions. The security

force usually consisted of a mechanized infantry company (minus one rifle

platoon) and a tank platoon. Because enemy base camps, tunnels, and other

installations were frequently uncovered, each security force contained a search

group of one infantry platoon and an engineer squad. When an enemy base camp

was discovered, the clearing team went on working while the search group gathered

information and enemy materiel before destroying the camp. The combined arms

force worked with the same plow team throughout the operation in order to

insure close teamwork.

-

- Before the plows began clearing, preparatory machine fire, mor-

- [148]

- tar, and tank canister fire was directed into the jungle. Once the first

swath, outlining the area to be cleared, was completed the security force

deployed in single file outside each plow team, with a tank section at the

front and rear of the column. To discourage ambushes, harassing fire was constantly

delivered on the uncleared jungle surrounding the working area. If enemy soldiers

were discovered, the security force immediately deployed and assaulted while

one platoon escorted the plows to safety. To prepare night defenses, plow

teams cleared firing lanes and dug positions for the tracked vehicles.

-

- In Rome plow operations along Route 20 from Blackhorse Base Camp to the

boundary between III Corps and II Corps, the 3d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry,

used a different procedure. Instead of keeping the bulk of its cavalry with

the plows, the squadron first cleared the immediate area to be cut, then left

a security force of two to four armored cavalry assault vehicles with the

plows. The remainder of the squadron conducted search and clear operations

around the area being worked to keep the enemy from entering. This method

became more common in later years. As emphasis on clearing along major roads

and in enemy base areas increased, Rome plow security operations became routine

for armored units. In the absence of established tactics, units used methods

whose variety was limited only by the ingenuity of the commanders.

-

- Tank Versus Tank

-

- Combat between tanks, for which U.S. tank crews traditionally train, materialized

only once for American armored units in Vietnam. Since the North Vietnamese

had armored forces in October 1959, when the 202d Armored Regiment was created,

their reasons for not making more use of them earlier can only be conjectured.3

Cadre from the regiment had joined the Central Office for South Vietnam

staff as armor advisers as early as 1962. The North Vietnamese Army established

an armor command in the summer of 1965, and by March 1973 there were more

than twelve armor units, ranging in size from battalion to regiment. The People's

Republic of China and the Soviet Union supplied all the armored vehicles,

which included armored personnel carriers, light tanks, and medium tanks.

The associated armored support vehicles, including self-propelled antiaircraft

weapons, were supplemented by captured U.S. M41 tanks. Although poorly managed

in early encounters,

- [149]

- enemy armored forces learned their lessons well, and in early 1975 actually

spearheaded the final assaults on South Vietnam.

-

- Contrary to American teaching on the subject, the North Vietnamese Army

did not advocate the use of tanks in mass. Its doctrine stated that armor

would be employed during an attack, when feasible, to reduce infantry casualties;

however, only the minimum number of tanks required to accomplish the mission

would be used. Battle drill dictated that lead tanks were to advance, firing,

and to be supported by fire from other tanks and from artillery. Close coordination

between tanks and supporting infantry was stressed as a key to success in

the attack. Because the North Vietnamese lacked air power, they placed strong

emphasis on camouflage training in armor units; in the spring offensive of

1972, tank regiments moved great distances without being detected.

-

- Until the end of 1973, North Vietnamese armor appeared on or-near the battlefields

of South Vietnam on only four recorded occasions. The first instance was at

Lang Vei Special Forces Camp near Khe Sanh in the I Corps area on 6-7 February

1968. Here, a North Vietnamese combined arms attack with PT76 tanks succeeded

in breaking through the camp's defensive positions. In 1969 at Ben Het the

North Vietnamese again used armor. Against the South Vietnamese Army force

that attacked into Laos in 1971, the North Vietnamese committed an entire

armor regiment and staged well-coordinated tank-infantry attacks. In their

spring offensive of 1972 in South Vietnam, the North Vietnamese used the largest

tank forces of the war. Entire tank companies stormed objectives, with infantry

troops following close behind.

-

- It was at Ben Het in March 1969 that American and North Vietnamese armor

clashed for the first and only time. The Ben Het Special Forces Camp in the

central highlands of the II Corps Tactical Zone overlooked the Ho Chi Minh

Trail where the borders of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam come together. In an

effort to mask nearby North Vietnamese troop movements, the enemy had subjected

the camp to intense indirect fire attacks during February.

-

- To counter an apparent enemy buildup, elements of the 1st Battalion, 69th

Armor, were sent to the area.4

Captain John P. Stovall's Company B, the forward unit of the battalion,

occupied strongpoints and bridge security positions along the ten-kilometer

- [150]

- road link between Ben Het and Dak To. One platoon of tanks was j stationed

in the camp. Free world forces at Ben Het included three Vietnamese infantry

companies and their Special Forces advisers, an American 175-mm. artillery

battery, and two M42's, tracked vehicles mounting 40-mm. twin guns on an M41

tank chassis. The M42's and the 175-mm. battery were in the main camp, while

most of the newly arrived tank platoon took up dug-in positions on a hill

facing west toward Cambodia. One tank, located in the main camp, occupied

a firing position guarding the left flank overlooking the resupply route.

Through February the platoon endured heavy enemy shelling by taking cover

in its armored vehicles and moving from bunker to bunker during quiet periods.

The crews fired their 90-mm. guns at suspected North Vietnamese gun sites

and bunkers on the rugged slopes. When the tank platoon leader was wounded

I and evacuated, Captain Stovall moved the company command post to Ben Het.

-

- Enemy shelling decreased in March, allowing defensive positions to be strengthened

and improved, and making the entire camp ready for instant action. For three

full days enemy fire abated, but at 2100 on 3 March 1969 the camp once again

began to receive mortar and artillery fire in crashing volleys. Both Sergeant

First Class Hugh H. Havermale and Staff Sergeant Jerry W. Jones heard the

sound of tracks and heavy engines through the noise of the artillery. With

no free world tanks to the west, the probability of an enemy tank attack sent

everyone into action. High explosive antitank (HEAT) ammunition was loaded

into tank guns and from battle stations all eyes strained into the darkness.

-

- In his tank, Sergeant Havermale scanned the area with an infrared searchlight,

but could not identify targets in the fog. Sergeant Jones, from his tank,

could see the area from which the tank sounds were coming but had no searchlight.

Tension grew. Suddenly an antitank mine exploded 1,100 meters to the southwest,

giving away the location of the enemy; the battle for Ben Het now began in

earnest.

-

- Although immobilized, the enemy PT76 tank that had hit the mine was still

able to fight. Even before the echo of the explosion had died, the PT76 had

fired a round that fell short of the defenders' position. The remainder of

the enemy force opened fire, and seven other gun flashes could be seen. The

U.S. forces returned the fire with HEAT ammunition from the tanks and fire

from all other weapons as well. Specialist 4 Frank Hembree was the first American

tank gunner to fire, and he remembers: "I only had his muzzle flashes

to sight on, but I couldn't wait for a better target

- [151]

- RUSSIAN-MADE PT76 TANK DESTROYED AT BEN HET

-

- because his shells were landing real close to us." The muzzle flashes

proved to be enough for Specialist Hembree; his second round turned the enemy

tank into a fireball.

-

- Capital Stovall called for illumination from the camp's mortar section and

in the light of flares spotted another PT76. Unfortunately, the flares also

gave the North Vietnamese tanks a clear view of the camp's defenses, and as

Captain Stovall was climbing aboard Sergeant Havermale's tank, an enemy high

explosive round hit the loader's hatch. The concussion blew Stovall and Havermale

from the tank, and killed the driver and loader. Damage to the tank was slight.

-

- Sergeant Jones took charge, dismounted, and ran to another tank which was

not able to fire on the enemy main avenue of approach. Still under hostile

fire, he directed the tank to a new firing position where the crew quickly

sighted a PT76 beside the now burning hulk of the first enemy tank. The gunner,

Specialist 4 Eddie Davis, took aim on one of the flashes and fired. "I

wasn't sure of the target," Specialist Davis said, "but I was glad

to see it explode a second later." Every weapon that could be brought

to bear on the enemy was firing. Having exhausted their basic

- [152]

- load of high explosive antitank ammunition, the tank crews were now firing

high explosives with concrete-piercing fuzes. Gradually, the enemy fire slackened,

and it became clear that an infantry assault was not imminent. In the lull,

the crews scrambled to replenish their basic load from the ammunition stored

in a ditch behind the tanks. Tank rounds were fired at suspected enemy locations

but there was no return fire. The remainder of the night was quiet;

the tension of battle subsided, and the wounded were evacuated.

-

- The battle for Ben Het had not gone unnoticed by the remainder of the 1st

Battalion, 69th Armor. Company A and the battalion command post moved to Polei

Kleng to reinforce ground elements and be in a position to counterattack population

centers. The 2d Platoon of Company B assembled and moved by night to Ben Het,

where a search of the battlefield the next day revealed two PT76 hulls and

an enemy troop carrier that had not been noticed during the battle but now

lay burned out and abandoned on the edge of the battlefield. The enemy vehicles

were part of the 16th Company, 4th Battalion, 202d Armored Regiment of the

North Vietnamese Army.

-

- Intelligence later revealed that the main object of the attack on Ben Het

was to destroy the U.S. 175-mm. guns. Whatever the enemy's intention, the

camp was held by American tanks against North Vietnamese tanks. Not until

March 1971, when South Vietnamese M41 tanks battled North Vietnamese

tanks in Laos, would tanks clash again.

-

- Invading the Enemy's Sanctuaries

-

- The battle that ended in the defeat of the enemy at Ben Het was only one

of an increasing number of attacks in which the enemy did not achieve military

victory. Free world forces were no longer content to sit back and wait for

North Vietnamese troops to make the first move. Base areas, once safe havens

for the enemy, were penetrated by large armored formations intent on disrupting

the enemy logistical system. General Abram's strategy of destroying the enemy

logistics nose was now in full swing.

-

- One of these operations was conducted during March and April 1969 by elements

of the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division in western Quang Tri Province of

the I Corps Tactical Zone. Operating in country long thought to be impenetrable

to armored vehicles, this combined arms team, designated Task Force REMAGEN,

demonstrated again the advantage of mechanized forces. Of special significance

during this operation was the lack of a ground line of com-

- [153]

- munications to the more than 1,500 men of Task Force REMAGEN. Helicopters

supplied the task force with over 59,000 gallons of diesel fuel and gasoline

and more than 10,000 rounds of 105-mm. artillery ammunition. Although the

task force encountered normal maintenance problems as it moved through the

rough terrain, tank power packs weighing over four tons and other major components

were delivered by helicopter. For forty-three days, the task force operated

in rugged terrain along the Laotian border on an aerial supply line, demonstrating

that even remote base areas were vulnerable to attack by armored units.

-

- The success of REMAGEN was not an isolated case, for the feat was duplicated

in the III Corps Tactical Zone. Operation MONTANA RAIDER, conducted from 12

April to 14 May 1969 in the area east and north of Tay Ninh City, was aimed

at a rear service support and transportation zone for enemy troops and equipment

entering South Vietnam from Cambodia. Although the exact location and identity

of enemy units in this region were not known, two North Vietnamese divisions

were thought to be present. The terrain was not rugged, but dense jungle hampered

movement. The MONTANA RAIDER force consisted of one infantry-heavy and two

armor-heavy task forces under command of the 11th Armored Cavalry. The regiment's

air cavalry troop and the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, the air cavalry squadron

of the 1st Cavalry Division, flew in support of the operation. An artillery

battalion headquarters under direct control of.the regiment coordinated all

artillery fire. A cover and deception plan was devised to persuade the enemy

that U.S. forces were moving north and west of Tay Ninh City. Air cavalrymen,

flying over enemy base camps, deliberately lost map overlays clearly marking

the area northwest of Tay Ninh City as an objective for the operation, and

intentional security breaches in radio transmissions were employed to the

same end.

-

- At 0800 on 12 April operational control of the 11th Armored Cavalry passed

from the 1st Infantry Division to the 1st Cavalry Division, marking the beginning

Of MONTANA RAIDER. In accordance with the deception plan, the armor-heavy

task forces left Bien Hoa and moved past the actual area of operations. As

the 11th Armored Cavalry's 2d Squadron task force neared Dau Tieng, it swung

northwest to join Company A of the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry (Airmobile),

while the l1th Cavalry's 1st Squadron task force moved into another base and

linked up with Company C of the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry. The movement through

and beyond the actual area of operations was designed to suggest further to

the enemy that the operation would be conducted northwest of Tay

- [154]

- Ninh City. By 1700 on 12 April all forces had completed the 98 kilometer

move and were ready for action.

-

- On 13 April Colonel James H. Leach, commander of the 11th Armored Cavalry

took operational control of an airmobile infantry unit, the 1st Battalion,

8th Cavalry, and began reconnaissance in force operations east to Tay Ninh

City. The 11th Cavalry's 1st Squadron task force entered the area from the

southwest, its 2d Squadron task force from the northwest, and the 8th Cavalry

task force from the northeast. In order to give the 8th Cavalry task force

additional firepower and some armored protection, Troop G and one platoon

of Company H, the tank company of the 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, were

attached. The first unit to clash with the enemy was the regimental air cavalry

troop, which was assessing bomb damage from a B-52 strike. After the aerorifles

and infantry reinforcements were sent in, Troop A of the 1st Squadron, 11th

Armored Cavalry, arrived, and in an all-day battle in the heavy jungle finally

drove the enemy out. The following days saw scattered fighting as the task

forces converged. Artillery and air strikes were used liberally to destroy

enemy base camps. The longest battle of Phase I occurred on 18 April when

Troops A and B of the 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, met a large enemy

force. Heavy artillery and air strikes were used against the enemy, but the

assault was delayed when machine gun tracer ammunition created a fire storm

in the bamboo thickets. The enemy lost seventy-six men in this battle.

-

- At the end of Phase I, and after two days devoted to maintenance, Phase

II opened with a 149-kilometer road march for the entire regiment to Quan

Loi in Binh Long Province, 100 kilometers north of Saigon. Phases II and III

saw the combined arms task forces of the 11th Armored Cavalry ranging throughout

eastern War Zone C, engaging the enemy in short, bitter fights, almost always

in heavy jungle. The stress again was on mobility, firepower, and the combined

arms team.

-

- MONTANA RAIDER demonstrated the versatility of a large, mounted unit, aggressively

led and employing conventional armored award doctrine in isolated jungle.

All three phases of MONTANA RAIDER again showed the value of combined arms

-armored cavalry, infantry, artillery, and air cavalry. Surprising mobility

was achieved by tracked vehicles, which covered more than 1,600 kilometers

during the operation; of that distance, 1,300 kilometers were in dense jungle.

More important was the fact that this operation, REMAGEN in the north, and

others throughout Vietnam put free world forces in possession of the enemy

base areas

- [155]

- during 1969. With nowhere else to go, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

pulled back to their bases in Cambodia and Laos.

-

- In the southern part of I Corps Tactical Zone, in the spring of 1969, a

similar base area operation was conducted in the A Shau valley along the Laos

border. Spearheaded by the 101st Airborne Division, it included eighty tracked

vehicles of the 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, and the 7th Vietnamese Armored Cavalry

Regiment. These were the first armored forces to operate in the A Shau valley.

-

- Securing the Borders

-

- After the success of operations against enemy sanctuaries in South Vietnam,

the next step was sealing the borders, or at least making them reasonably

secure. With the growing demands of pacification and the prospect of troop

withdrawals, which would limit the resources available, the task naturally

fell to mobile units, both ground and air, that could move rapidly and control

large areas. Armored and airmobile units became the mainstay of border operations,

particularly those in the critical III Crops area north of Saigon.

-

- Based at Phuoc Vinh, the 1st Cavalry Division, with three brigades of airmobile

infantry and operational control over the 11th Armored Cavalry, was extended

among more than a hundred kilometers of border from east of Bu Dop to northwest

of Tay Ninh City, opposite enemy base area 354. The 25th Infantry Division

controlled the western and southern approaches to Saigon, and the 1st Infantry

Division commanded the entrances to the Saigon River corridor and the old,

now quiet war zones in southern Binh Long and Phuoc Long provinces.

-

- Border operations of the armored cavalry, the air cavalry, and the airmobile

infantry of the 1st Cavalry Division illustrate the tactics of both sides

in the conflict. As the enemy tried to cross the border in strength, supported

from bases beyond South Vietnamese boundaries, the defenders attempted to

prevent the crossing with firepower and maneuver. By early 1970 the cavalry

and airmobile infantry forces had developed some sophisticated techniques

employing Rome plow cutting, sensors, and automatic ambush devices to deny

the use of trails to the enemy. These techniques were first applied systematically

in the northwestern part of the III Corps area from Bu Dop to Loc Ninh along

QL-14A, and almost immediately produced good results. (See Map 13, inset.)

The 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, controlled this region from Fire

Support Base Ruth outside Bu Dop and patrolled east and west along the Cambodian

border.

- [156]

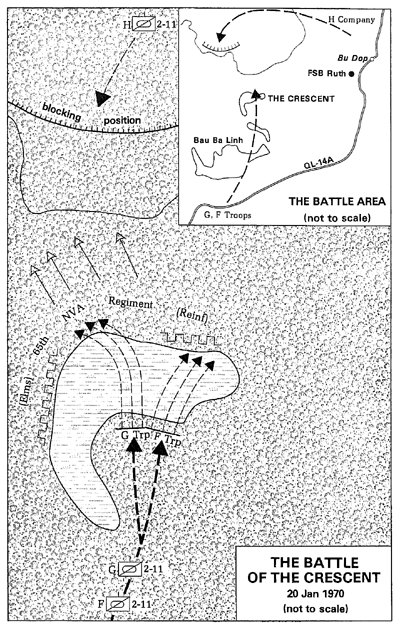

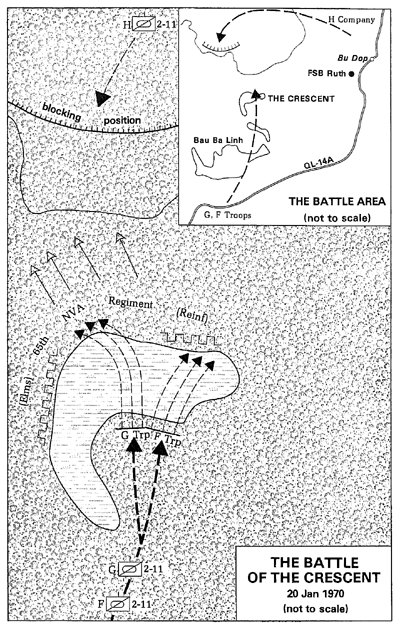

- Early on the morning of 20 January 1970, as Lieutenant Colonel Grail L.

Brookshire, commander of the 2d Squadron, and Colonel Donn A. Starry, the

regimental commander, conferred at Fire Support Base Ruth, a deluge of mortar

and rocket fire descended on the base. Both commanders took off in helicopters,

and while Colonel Brookshire gathered his squadron Colonel Starry requested

tactical air, air cavalry, and artillery fire support. Two battalions of the

65th North Vietnamese Regiment and part of an antiaircraft regiment had occupied

a dry lake bed about three kilometers west of the base; it was from near this

crescent-shaped opening in the otherwise dense jungle that the indirect fire

attack on the base began. (Map 13) Later it was learned that the enemy

had hoped to lure the American forces into an airmobile assault into the clearing,

where carefully sited antiaircraft guns would have devastated such a force.

-

- As gunship, tactical air, and artillery fire was brought in, a scout helicopter

was shot down, leaving the wounded pilot stranded in a bomb crater. The 2d

Squadron began to move to the location, with the tanks of Company H approaching

from the north and the cavalry of Troops F and G from the south. A Cobra pilot,

Captain Carl B. Marshall, located the flaming wreckage and spotted the wounded

pilot, First Lieutenant William Parris, waving from the bomb crater. Captain

Marshall flew in low and landed nearby in a hail of machine gun and mortar

fire. Lieutenant Parris raced to the aircraft and dove into the front seat,

where he lay across the gunner's lap, legs danging from the open canopy, as

Captain Marshall pulled up, barely clearing the wood line.

-

- Artillery, fighter bombers, and gunships descended on the enemy, while Troop

F hastened up Highway 14A to link up with Troop G. which was already heading

north. After crossing a meadow near Bau Ba Linh and a seemingly unfordable

stream, Troop G bore into the jungle. Ninety minutes and two kilometers of

single and double canopy jungle later, Troop G arrived, joined Troop F, and,

on line, the cavalry assaulted. From the helicopter Colonel Starry had meanwhile

called for an airdrop of tear gas clusters on enemy bunkers toward the north

side of the crescent. Colonel Brookside halted the artillery fire long enough

for the drop, which brought the enemy troops out of the bunkers and sent them

running north for the border. Colonel Brookshire then ordered artillery and

gunship fire while Troops G and F attacked through the enemy positions. Company

H, in position north of the crescent, caught the fleeing enemy with canister

and machine gun fire.

- [157]

- MAP 13

- [158]

- The ground forces continued to fight and maneuver until nightfall. Darkness

prevented a detailed search, and the next morning the 2d Squadron pulled out

at dawn. The fight had lasted almost fourteen hours, with over 600 rounds

of artillery fired, thirty tactical strikes employed, and fifty Cobra rocket

loads delivered. The 65th North Vietnamese Regiment did not appear again in

battle for nearly four months. Colonel Brookshire's search of the crescent

was broken off abruptly as he moved to reinforce the regiment's 1st Squadron,

fighting near An Loc.

-

- Early on 21 January 1970, thirty-five kilometers to the west, the 1st Squadron,

which was operating in a Loc Ninh rubber plantation, intercepted two North

Vietnamese battalions moving south into Loc Ninh District. The 11th Armored

Cavalry piled on with Colonel Brookshire's 2d Squadron racing in from the

crescent battleground to the northeast and Lieutenant Colonel George C. Hoffmaster's

3d Squadron attacking north along Highway 13 out of An Loc. Over half of the

regiment converged on the fight in less than three hours and broke the back

of the enemy attack. The two North Vietnamese battalions ran for cover in

Cambodia, with elements of the cavalry pursuing them to the border. The pursuit

was aided by a map found on the North Vietnamese commander that showed the

escape plan. Those fugitives who reached the escape routes were met by tactical

air and artillery fire. After these two fights and a few more with the same

outcome, the enemy showed reluctance to risk a fight with the cavalry, whose

mobility and firepower had been overwhelming.

-

- Operations along Highway 14A were so successful in drying up enemy logistical

operations along the jungle trails that it was decided to repeat the scheme

in War Zone C. The plan was to stop the supply operations of the enemy's 50th

Rear Service Group operating out of the Cambodian Fishhook area into the Saigon

River corridor through War Zone C. The American forces were to conduct extensive

land clearing operations along Route 246, generally east and west across War

Zone C, thus blocking the north and south trails from Cambodia to the Saigon

River corridor.

-

- By mid-February Rome plows had cleared a swath of jungle 400 to 500 meters

wide along Highway 246 from An Loc in Binh Long Province to Katum in Tay Ninh

Province, just south of the border. Along this cut the 11th Armored Cavalry

began operations. The 3d Squadron anchored the east flank near An Loc, the

2d Squadron held the middle, and the 1st Squadron covered the west in northwestern

Tay Ninh Province. Airmobile infantry battalions of the 1st Cavalry Division,

operating south in War Zone C, fre-

- [159]

- quently under control of the 11th Armored Cavalry, completed the interdiction

force.

-

- Colonel Starry was convinced that to cut enemy supply lines successfully

ground had to be held, and that control of the ground followed from constant

use of the ground. The operational pattern of the regiment, therefore, was

one of extensive patrolling, day and night, and the setting up of an intricate

network of manned and unmanned ambushes all along the trail system. The cavalry

soon came to know the enemy's trails well, and by clever use of automatic

devices reduced enemy logistical operations to a trickle. The ambush net cost

the enemy ten to thirty casualties each night. Every site was checked, and

electrical devices were moved and reset each day. It was like running a long

trapline.

-

- Monitoring enemy radio traffic, the 11th Armored Cavalry learned that enemy

units to the south were desperate for food and ammunition. Enemy relief parties

were killed in ambushes or by cavalry units that took advantage of information

gleaned from careless enemy radio operators. Enemy messengers sent along the

trails were killed or captured; their messages and plans provided information

for setting up more traps.

-

- The enemy, reluctant to confront the cavalry directly, attacked only by

fire in War Zone C, and tried to outflank the net of ambushes. The 209th North

Vietnamese Army Regiment lost over 200 men when it ran headlong into Captain

John S. Caldwell's Troop L, 3d Squadron, in the Loc Ninh rubber plantation

in March. Later, in April, the 95C North Vietnamese Regiment, trying to move

west around the ambush system, encountered Lieutenant Colonel James B. Reed's

1st Squadron near Katum. With the cavalry and tanks of the 1st Squadron heavily

engaged, Colonel Starry alerted Colonel Brookshire to move two troops from

the 2d Squadron west to join in the fight. The enemy now had two battalions

locked in combat with the 1st Squadron, while a third battalion was escaping

to the north. Realizing he faced the cavalry regiment, the enemy commander

panicked and began broadcasting instructions to his battalions in the clear.

As the enemy troops tried to disengage, intercepts of the instructions they

were receiving were passed to Colonel Reed. Armed with this information, the

1st Squadron blocked the enemy. In the ensuing melee the cavalry squadrons

virtually destroyed the two battalions opposing Colonel Reed. Some of the

third battalion to the north escaped despite air strikes and artillery fire

placed along the escape routes.

-

- It was more than six months before the North Vietnamese 95C Regiment fought

again. The extensive system of Rome plow cuts

- [160]

- and the presence of cavalry and airmobile forces in late 1969 enabled free

world forces to choke off enemy supply lines and neutralize bases in War Zone

C. More so than at any other period in the war, except when the attacks were

made into Cambodia, enemy access to South Vietnam was cut off.

-

- Pacification Efforts

-

- While operations against the sanctuaries and along the border were in progress,

important steps were taken to win over the people in areas long under enemy

control. In the spring of 1969 major enemy action had diminished to a level

that offered an opportunity for large-scale efforts in this direction. On

13 April 1969 the 173d Airborne Brigade began Operation WASHINGTON GREEN,

which would occupy the brigade for the next nineteen months. The mission called

for placing one mechanized and three infantry battalions in four densely populated

districts of Binh Dinh Province in the II Corps Tactical Zone. Primary emphasis

was to be given village and hamlet protection in order to enable territorial

forces, in conjunction with other government agencies, to conduct searches

behind a protective shield of South Vietnamese Army and American forces. U.S.

troops were usually present at first to supplement weak local security forces

until recruitment and training would permit replacement of American by Vietnamese

units. The 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry (Mechanized) , was assigned to Phu

My District for most of this operation.

-

- Even large units such as the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized)

, became totally involved. In January 1970 the brigade launched Operation

GREEN RIVER, designed to further the pacification program in the northern

I Corps area by conducting combined operations with the South Vietnamese 1st

Infantry Division. Reconnaissance in force, search and clear operations, and

measures against enemy rockets were undertaken throughout Quang Tri Province.

-

- By 1970 many American units were committed to securing large areas in the

interest of the South Vietnamese government's pacification program, and some

armor units had that as a primary mission. Extensive surveillance operations

were conducted along the Demilitarized Zone to prevent enemy infiltration,

and security screens were established around populated and militarily significant

areas.

-

- Forces in Operation GREEN RIVER killed over 400 of the enemy in six months.

As GREEN RIVER ended, units of the brigade began Operation WOLFS MOUNTAIN,

which lasted into January 1971.

- [161]

-

A TANK OF THE 2D BATTALION, 34TH ARMOR, IN POSITION TO

PROVIDE STATIC ROAD SECURITY

-

- Combined operations were conducted by the brigade, the South Vietnamese

1st Infantry Division, and territorial forces throughout northern Quang Tri

Province. The operations included the use of armored forces as security along

the Demilitarized Zone, on lines of communication, and around populated areas.

-

- Pacification efforts and measures to aid the Vietnamese armed forces to

assume the full burden of the war intensified in mid-1969 with U.S. troop

withdrawals. The South Vietnamese Army undertook a program to expand the armored

cavalry from ten to seventeen regiments. Even more noteworthy was the activation

of two armor brigade headquarters, which allowed South Vietnamese armored

units to operate in larger formations. Both the I and IV Armor Brigades deployed

to their respective corps tactical zones during 1969, and were soon followed

by two more brigades. Each armor brigade was a highly mobile, independent,

tactical headquarters that could control ten to twelve squadrons.

-

- On 22 and 23 May 1969, a joint Vietnamese-American armor conference convened;

attending were the South Vietnamese Chief of Armor, with his staff and his

American advisers, and all South

- [162]

- Vietnamese armor regimental commanders and their American advisers. Their

purpose was to review South Vietnamese armor and set goals for its future

development. The key question was whether current missions were making full

use of armored units. The general response was no. Fragmenting of armored

units, static missions, the use of tanks as pillboxes, and assigning armored

forces permanent areas of operation were the most common mistakes singled

out by South Vietnamese armor leaders. The South Vietnamese Armor Command

made an honest effort to evaluate itself, and took positive action to improve

its performance.

- In November 1969 the Vietnamese Joint General Staff published a directive

on employment of Vietnamese armored units. The directive first noted improper

uses that had been described by the armor commanders, and then added that

many units had failed to provide logistical support for armored units assigned

to them. It directed certain corrective actions.

-

- 1. Avoid the use of armored forces in static security missions.

-

- 2. Do not divide armored units below troop level.

-

- 3. Give missions of reconnaissance and search and destroy in large operational

areas.

-

- 4. Use armor brigade and regimental headquarters to direct and control combined

arms operations.

-

- 5. Use armored units in night operations with the support of organic searchlights,

mortars, flares, artillery, and aircraft.

-

- 6. Develop U.S. and Vietnamese combined operations.

-

- This analysis of the South Vietnamese Army's use of armor and the subsequent

directive from the joint General Staff put backbone into South Vietnamese

armor doctrine. Although it ruffled some feelings in the Vietnamese command,

improvements in field use were noticed immediately. In February 1970 the 1st

Armored Brigade conducted mobile independent operations along the sea in the

northern part of the I Corps Tactical Zone. Controlling up to two regiments

of cavalry, Rangers, and territorial forces, for two months the brigade roamed

over the area and succeeded in destroying three enemy battalions. As part

of the operation, 5,000 acres of land were cleared. The enemy was effectively

defeated and moved away; Regional and Popular Forces units moved in and established

permanent settlements. Almost 900 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese were killed

or captured, while the brigade lost sixty-eight men. For success in its first

large-scale operation, the Vietnamese 1st Armored Brigade was awarded a U.S.

Presidential Unit Citation.

- [163]

- Vietnamese Forces Take Over the War

-

- In the United States, as the newly elected president, Richard M. Nixon,

prepared to take office in Washington in late 1968, the single most vexing

problem confronting the administration was Vietnam. Unable to resolve the

issue satisfactorily, Lyndon B. Johnson had chosen not to seek another term.

In response to instructions from Washington, U.S. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker

and General Abrams had privately discussed with President Thieu, the possibility

of withdrawing some American forces. By January 1969 these conversations had

expanded into specific proposals for sending home first one, then two American

divisions. Then, in April, the new administration issued National Security

Study Memorandum 36, directing preparation of plans for turning the war over

to the Vietnamese.

-

- In Vietnam plans were drawn up in strictest secrecy, under the careful eye

of General Abrams himself by a very small task force headed by Colonel Starry.

At the outset the idea that withdrawal of a single American soldier would

cause the collapse of the whole war effort was, to use the words of General

Abrams "simply unthinkable." General Abrams, however, was firmly

convinced that the Vietnamese Army could do more. He drew considerable confidence

from the growing success of the pacification effort, and, always a practical

man, he realized, that like it or not, the new administration was committed

to withdrawing some or all American forces. His instructions to Colonel Starry

were quite clear: ". . . do it right, do it in an orderly way . . . save

the armor units out until last, they can buy us more time." Thus armor

units, specifically excluded from the buildup until late 1966, would anchor

the withdrawal of American combat units from Vietnam.

-

- On 9 June 1969 President Nixon met President Thieu at Midway Island and

they agreed to the first withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam-25,000 men.

On 13 July Company C, 3d Marine Tank Battalion, became the first U.S. armor

unit to leave South Vietnam as one battalion landing team of U.S. marines

boarded its amphibious ships. Troop withdrawals continued at an ever-accelerating

pace, even while large-scale operations, such as the incursion into Cambodia

of 1970 and the enemy offensive of early 1972 were in progress. From the beginning,

force planners held out armored units-tanks, air cavalry, ground cavalry,

and mechanized infantry. As divisions or brigades left the country, their

armored units remained behind. The mobility and firepower of armored units

made them the logical choice for operations over extended areas, and rearguard,

delay, and economy of force roles were traditional armor

- [164]

- specialties, particularly for cavalry. Thus, when the 9th Infantry Division

departed in 1969, the 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized) , and the 3d

Squadron, 5th Cavalry, remained behind. Almost every air cavalry unit remained

in Vietnam until early 1972. These armored units provided a maximum of firepower

and mobility with a minimum of U.S. troops. By the end of 1970, with the withdrawal

of American units in high gear, fourteen armored battalions or squadrons remained

in Vietnam. In December 1971 armored units represented 54 percent of the U.S.

maneuver battalions still in Vietnam.

-

- The U.S. armored units that remained supported and trained Vietnamese forces

while combat operations were carried out. One such unit, the U.S. 7th Squadron,

1st Cavalry (Air) , supported the Vietnamese 7th, 9th, and 21st Infantry Divisions

in the delta and along the Mekong River corridor to Cambodia. On occasion,

air cavalry units used South Vietnamese troops as aerorifle platoons. In addition,

the squadron trained Vietnamese pilots in a program calling for three months

or 180 hours of flight time for each pilot. During this successful program,

it was found invaluable to have an individual who spoke Vietnamese aboard

each American helicopter while the aircraft were supporting South Vietnamese

operations. Troop D, the ground troop of the squadron, provided instruction

in small unit tactics for Vietnamese Regional and Popular Forces.

-

[165]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-