- Chapter VII:

-

- Across the Border: Sanctuaries

in Cambodia and Laos

-

- As early as 1965 the North Vietnamese used areas of Cambodia and Laos near

the borders of South Vietnam as sanctuaries in which to stock supplies and

conduct training without interference. It was in these countries that the

North Vietnamese built the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail as their principal supply

route to the south. As time wore on and the tempo of the war increased, the

word trail became a misnomer, for a primitive network of jungle paths had

grown into a vast system of improved roads and trails, many of which could

be used the year-round. The image of a North Vietnamese soldier-porter trudging

south from Hanoi for six months with two mortar shells destined for South

Vietnam could no longer be conjured up. By late 1968 the North Vietnamese

were moving most of their supplies by truck, pipeline, and river barge.

-

- This relatively sophisticated transportation system terminated at depots

within and adjacent to South Vietnam. Combat units in South Vietnam received

supplies from these depots by a simpler but highly organized system of distribution

that made use of small boats, pack animals, and porters. In the late 1960's,

as the free world forces extended their operations into the enemy base areas

in South Vietnam, the enemy regular forces expanded the bases and depots across

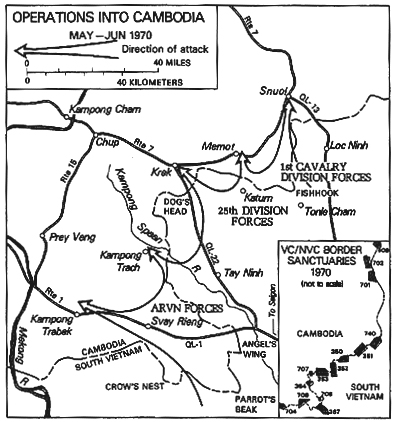

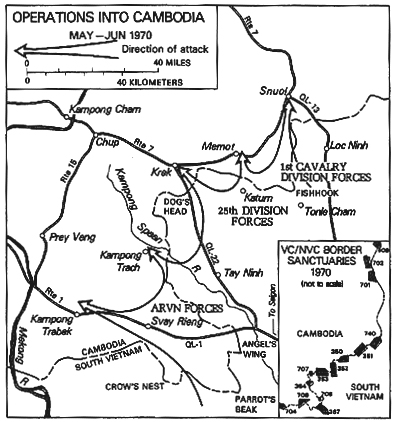

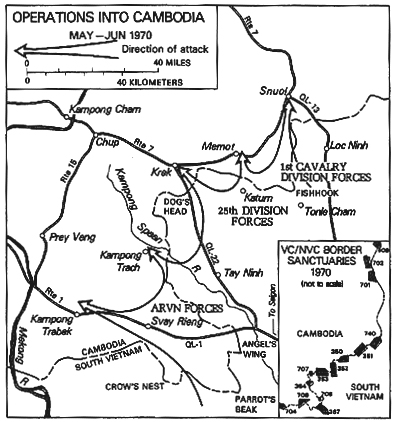

the borders in Cambodia and Laos. (,See Map 14, inset) . Since for

political reasons these base areas were inviolate, they provided sanctuaries

to which the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong units could retire periodically

from combat in South Vietnam, train and refit, and return to combat. Free

world forces called these sanctuaries base areas, since they provided not

only supply and maintenance facilities but also training and maneuver areas,

classrooms, headquarters, and even housing for families of soldiers.

-

- The Cambodian government, under pressure from North Vietnam and China, had

for several years conceded these areas to the enemies of South Vietnam. In

March 1970, however, Marshal Lon Nol of Cambodia seized control of the government.

and began a campaign to restrict the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese in their

use of his country. Lon Nol's efforts hinged on a proposal that would allow

them to continue to use some base areas, but under Cambodian control. Since

it would have severely hampered

- [166]

- movement of Cambodian-based enemy troops and supplies to and from South

Vietnam, the proposal was rejected by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese,

who moved to occupy major portions of eastern Cambodia.

-

- The coalition government of Laos had an arrangement with North Vietnamese

sympathizers that did not permit it to object to Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

operations in Laos. Base areas and their supporting transportation networks

in Laos therefore continued to provide critical support for North Vietnamese

forces operating in South Vietnam, and were a thorn in the side to the free

world forces. At one time or another most free world soldiers had seen Viet

Cong and North Vietnamese troops moving with impunity on the other side of

the ill-defined border.

-

- Early Operations Into Cambodia

-

- As the Cambodian situation became worse, the Cambodian government sought

military assistance from the United States and South Vietnam. In response

the South Vietnamese Army III Corps headquarters launched TOAN THANG 41, a

three-day operation into the so-called Angel's Wing, an area in Cambodia long

used by the enemy for resting and refitting units. Three South Vietnamese

Army task forces, each containing armored cavalry and Ranger units, began

the operation at 0800 on 14 April 1970. They were supported in South Vietnam

by the U.S. 25th Infantry Division. At midday, eight kilometers inside Cambodia,

a sharp fight broke out, and fierce hand-to-hand combat continued until late

afternoon, when the enemy broke away and fled. The next day the capture of

several base camps revealed the full extent of enemy logistical operations

in Cambodia. Plans called for the Vietnamese Air Force to evacuate captured

supplies, but because of the inexperience of the Vietnamese in large-scale

logistical airlift operations most material had to be evacuated by truck or

tracked vehicle. What could not be removed was destroyed. In all, 378 of the

enemy were killed and 37 captured. Eight South Vietnamese soldiers were killed.

Success brought confidence to the South Vietnamese government and the army.

-

- Thus encouraged, the South Vietnamese Army decided to expand operations

into the Crow's Nest area on 20 April 1970. The expedition was planned by

the South Vietnamese, and involved three armored cavalry regiments and. three

Ranger battalions under control of the Vietnamese 4th Armored Brigade. The

attack lasted three days, and again was conducted without U.S. advisers or

U.S. support once the troops were across the border. After two days of

- [167]

- costly defeats, the enemy fled, and the South Vietnamese forces turned to

evacuating large quantities of captured weapons and ammunition. The difficulties

experienced in using armored cavalry assault vehicles to haul captured equipment

prompted field commanders to request that in future operations ammunition

caches be destroyed.

-

- On 28 April the Vietnamese 2nd and 6th Armored Cavalry Regiments and Vietnamese

Regional Forces attacked again into the Crow's Nest. American advisers were

still not allowed on the ground in Cambodia, but for the first time U.S. support

was used-command and control helicopters and gunships. The attack penetrated

many enemy bases and diverted enemy attention from the larger attacks in III

Corps Tactical Zone.

-

- These early raids, a prelude to the major effort, helped to improve South

Vietnamese procedures and techniques for use in more open warfare. They also

afforded the free world forces a brief but eye-opening look at the massive

size of the support facilities located across the border. Materiel and intelligence

information confirmed in military minds the absolute necessity for large-scale

operations into all the base areas. As a result of the attacks, the frustration

built up over five years was vented, and success caused confidence and morale

in the South Vietnamese Army to soar. Unfortunately, these operations also

served to warn the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese that more attacks could

be expected, and a hasty exodus of enemy units and headquarters to the west

and north began.

-

- After the enemy offensives of 1968, the tactics of free world forces underwent

a change; from defensive, counterinsurgency tactics the allies began moving

toward the offensive and toward the employment of more conventional tactics.

The operations to secure the borders and clear the base areas in South Vietnam

heralded this change. In the massive attacks into the border sanctuaries,

which resembled exploitation or pursuit in conventional warfare, the change

in tactics reached full course, and at all levels of command the difference

was perceptible.

-

- The Main Attack Into Cambodia

-

- The major attack into Cambodia was a series of operations jointly planned

and conducted by South Vietnamese and American units, directed at the highest.

levels, and involving the headquarters and forces of the South Vietnamese

Army in the III and IV Corps zones and the U.S. II Field Force, Vietnam. When

it began, Operation TOAN THANG 42, the Vietnamese portion, was probably the

best planned South Vietnamese operation to that date. Weather

- [168]

- and terrain were important considerations; it was recognized that any delay

would invite considerable difficulties since the monsoon season would begin

in late May. The weather in late April and early May would be good. The area

chosen for the first attack was flat, with few natural obstacles to cross-country

movement. The operation was planned by III Corps headquarters under conditions

of great secrecy, and the participating Vietnamese units received only sketchy

details until the plan was released on 27 April.1

Early in the planning stage American advisers to South Vietnamese

units acted as coordinators rather than advisers. Once the operation began,

advisers were responsible for requesting and controlling American aid in the

form of medical evacuation, close air support, and artillery fire. The advisers

remained with their Vietnamese units up to thirty kilometers inside Cambodia;

a presidential decree banned all U.S. ground participation beyond the thirty-kilometer

line.

-

- The operation was planned so that U.S. and South Vietnamese forces were

separated by well-defined boundaries although they attacked simultaneously.

This arrangement considerably simplified coordination and logistical planning

and avoided possible confusion on the ground. The attack resembled a large

double envelopment, with the South Vietnamese forces forming most of the western

pincer and the American forces the center and the eastern pincer. (Map

14) Throughout the attack Vietnamese forces operated in combined arms

task forces with infantry, artillery, and armored cavalry. The one exception

was in the east in the airmobile assault of a South Vietnamese airborne brigade

under U.S. control.

-

- Operation TOAN THANG 42 began at 0710 on 29 April, less than forty-eight

hours after the participating units were informed, when South Vietnamese task

forces attacked to destroy enemy forces and supplies in Cambodia's Svay Rieng

Province. The mission included opening and securing National Highway 1 to

allow the evacuation of Vietnamese refugees and assisting the hard-pressed

Cambodian Army to regain control of its territory.

-

- All three task forces moving south and west in the Angel's Wing met the

enemy during the first two days. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese had anticipated

the attack and fought a stubborn delaying action, hoping to evacuate supplies

and equipment. Nonetheless, the first objectives were quickly achieved, and

on 1 May the

- [169]

- MAP 14

-

- South Vietnamese swept west to the provincial capital of Svay Rieng, opening

Route 1 to the east to Vietnam. The speed and success of this attack had in

part been made possible by lessons learned in previous forays. The advance

had been preceded by heavy air and artillery attacks on key areas inside Cambodia.

Unlike the procedure in previous operations, assault units kept on attacking

while follow-up units were responsible for the removal of captured supplies.

-

- While the enemy's attention was riveted on the Angel's Wing region, the

eastern pincer of the envelopment, TOANG THANG 43, was to attack under the

command of Brigadier General Robert L. Shoemaker, assistant division commander

of the 1st Cavalry Division (Air) . His task force included the 3d Brigade

of that division,

- [170]

- the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor (-), the 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized),

the South Vietnamese 3d Airborne Brigade, and the U.S. 11th Armored Cavalry.2

-

- Following intensive air and artillery bombardment, the airborne brigade

was to stage a helicopter assault into the area north of the Fishhook to seal

off escape routes, while ground units attacked north. Air cavalry was to conduct

screening operations as South Vietnamese cavalry screened the east flank in

Vietnam. Task Force Shoemaker's mission was to locate and eliminate enemy

forces and equipment. There was also a possibility that the Central Office

for South Vietnam, the elusive enemy headquarters, would be found in the Fishhook

and could be destroyed.

-

- At 0600 on 1 May, U.S. artillery fire exploded on the proposed helicopter

landing zones; the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry (Air) , began aerial reconnaissance

and was the first unit to find the enemy. Company C, 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry

(Mechanized), closely followed on the west by the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor,

led the attack of the 3d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) at 0945.

To the east the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was hit at the border by elements

of two enemy battalions. From their command vehicles with the lead tank platoon

of the 2d Squadron, Colonel Donn A. Starry, the regimental commander, and

Lieutenant Colonel Grail L. Brookshire, commanding the 2d Squadron, directed

tactical air and artillery fire that immediately suppressed the enemy fire.

The 11th Cavalry crossed the border at 1000.

-

- The 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized), and the 2d Battalion, 34th

Armor, proceeded north, unopposed, to secure landing zones to be used later

in the day by the 3d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division 3

The 2d and 3d Squadrons, 11th Cavalry, moved north with little opposition

until late afternoon when Company H entered a clearing six kilometers inside

Cambodia. Overhead, a scout helicopter from the regimental air cavalry troop

discovered a large enemy force well entrenched on the edge of the clearing.

The jungle suddenly erupted with enemy fire, and it quickly became evident

that the enemy was on three sides of the 2d Squadron.

-

- Colonel Starry immediately directed Lieutenant Colonel Bobby

- [171]

- F. Griffin, 3d Squadron commander, to attack the flank of the enemy defenses.

The air cavalry hit the enemy's rear and his withdrawal routes, and at 1645

the enemy force, estimated at a battalion, broke and fled, leaving fifty-two

dead. Two troopers of the 11th Cavalry were killed, the only American soldiers

to die in Cambodia on 1 May.

-

- By afternoon on 2 May free world forces were fighting in both wings of the

envelopment. The South Vietnamese forces in the Parrot's Beak attacked south

with two task forces from the III Corps Tactical Zone, while three task forces

from IV Corps attacked north.4

The object was to trap the enemy with elements of nine cavalry regiments.

The 7th Squadron, 1st Cavalry (Air), sweeping ahead and to the flanks, had

one troop credited with killing over 170 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. The

rapidly moving cavalry squadrons and U.S. air cover quickly broke the resistance

of enemy troops and chased them into the guns of the other South Vietnamese

task forces. The two South Vietnamese forces linked up early on the afternoon

of 4 May. Over 400 of the enemy were killed; 1,146 individual weapons, 174

crew-served weapons, more than 140 tons of ammunition, and 45 tons of rice

were captured.

-

- In the eastern wing on 2 May, the 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry (Mechanized),

cut Route 7 near Memot (Memut) ; the 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, linked

up with the South Vietnamese airborne forces. A search for supply caches met

little resistance from enemy security forces.

-

- Late on 3 May the 11th Cavalry was ordered to attack north forty kilometers

to take the town of Snuol and its important road junction. Route 7, leading

north to Snuol through large rubber plantations, was chosen as the axis of

advance, and by early afternoon on the 4th, the lead tanks had broken out

of the jungle and were on the ridge astride the highway. Once on the road

the 2d Squadron, followed by the 3d, raced north at speeds up to sixty-five

kilometers per hour and reached the first of three destroyed bridges by midafteroon.

The cavalry secured the site, placed I an armored vehicle launched bridge

across the stream, and went on.5

-

- With his regiment now strung out for almost sixty kilometers, Colonel Starry

decided to consolidate south of the second stream

- [172]

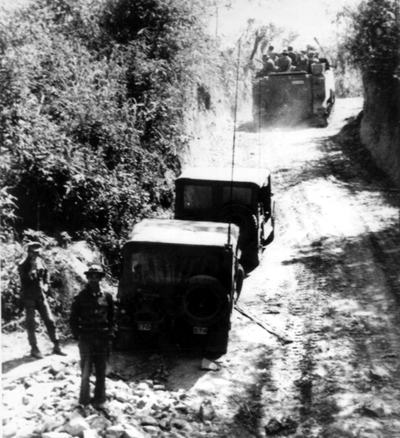

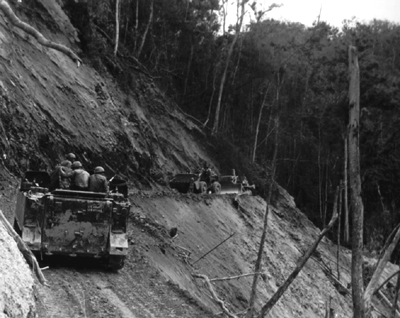

- THE 2D SQUADRON, 11TH ARMORED CAVALRY, ENTERS SNUOL, CAMBODIA

-

- crossing. Through the night, the 2d and 3d Squadrons closed on the lead

elements, which were now reconnoitering the two remaining crossings. The 11th

Armored Cavalry Regiment continued north on 5 May after Company H and Troop

G laid another vehicle launched bridge at the second crossing site. The third

crossing posed serious problems because it would require heavy bridging. A

flying crane, the CH-54 helicopter, was requested to transport an M4T6 bridge

to the site, but by midday when the 2d Squadron reached the third crossing

site the crane pilots and the engineers had made little progress. Anxious

not to lose the momentum of the attack, Colonel Starry set out on foot with

the section sergeant and the bridge launching vehicle to find a place where

the span could be used. After gingerly testing several places, they let down

the bridge, tried it out with Troop G, and by 1300 the 2d and 3d Squadrons

were again rolling north.

-

- The 2d Squadron paused south of Snuol to bring up artillery, organize air

support, and reconnoiter. Refugees reported that there were many North Vietnamese

troops in the town and that the civilians had fled. Scouts from the regimental

air cavalry troop had observed heavy antiaircraft fire all around the airstrip

to the east of town. In midafternoon the 11th Cavalry surrounded the city,

with the 2d Squadron on the east and the 3d Squadron on the west. As tanks

and armored cavalry vehicles rumbled across the Snuol airstrip, they were

hit by rocket propelled grenades and small arms

- [173]

- fire, which ceased abruptly when the tanks replied with cannister. After

a brisk fight, the antiaircraft guns were seized.

-

- The 3d Squadron, meanwhile, moving through the rubber trees to encircle

the town, triggered an ambush set to hit the 2d Squadron. Colonel Griffin

placed artillery fire behind the enemy position, set up gunships to cover

the right flank, and attacked with Troop I. As the 2d Squadron moved in from

the southeast in a coordinated attack, an inexperienced gunship pilot fired

rockets into the lead elements. This unfortunate incident caused the gunships

to be withdrawn and opened one side of the trap as an escape route for the

enemy. The two-squadron attack, however, routed the enemy troops, who fled

in small groups in all directions. When the cavalry entered Snuol, the city

was deserted.

-

- Snuol was apparently the hub of an extensive logistical operation. On the

following day, 6 May, the 2d Squadron discovered an improved road, large enough

for trucks and carefully hidden under the jungle canopy. Along the road the

cavalry found and destroyed an abandoned truck convoy laden with supplies.

The cavalrymen also discovered in Snuol a fully equipped motor park, complete

with grease racks and spare parts, and a large storage site containing 85-mm.

tank glen ammunition.

-

- While American units were attacking toward Snuol, South Vietnamese armored

task forces in the southwest were expanding their area of operation to the

north. Finding only disorganized enemy groups, the well-coordinated Vietnamese

units quickly reached the Kampong Spean River and secured Kampong Trach. To

the west of the town, an armor-heavy force overcame stiff resistance from

three North Vietnamese battalions. The attacking armored units were closely

followed by dismounted Rangers who eliminated the bypassed pockets of the

enemy. This coordinated combined arms attack, supported by tactical air and

artillery, demonstrated that the problems encountered during earlier South

Vietnamese operations had been solved.

-

- On 7 May President Nixon announced his satisfaction with the progress of

the operations, and stated that U.S. troops would be withdrawn from Cambodia

by 30 June. This announcement brought intensified search efforts, prompting

additional attacks into Cambodia in the Dog's Head area and toward Krek by

units of the 25th Infantry Division. The 1st Brigade moved on 14 May to come

abreast of the 2d Brigade, which had been committed earlier in the Fishhook

area. The move was led by the 2d Battalion, 22d Infantry (Mechanized) , the

1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized) , and elements of the 3d Squadron,

4th Cavalry. These troops were to act as a blocking force north of the Kampong

Spean

- [174]

- for the South Vietnamese task forces that were now moving from Svay Rieng

west to Kampong Trabek. Advancing in two columns on Route 1, and bypassing

several small forces, a South Vietnamese task force covered over thirty kilometers

to Kampong Trabek in slightly over two hours and linked up with South Vietnamese

forces from IV Corps who were moving north toward Phnom Penh.

-

- As the 18th Armored Cavalry Regiment was moving toward the linkup, the 15th

Armored Cavalry Regiment collided with the 88th North Vietnamese Regiment,

which was about to attack the 18th Armored Cavalry from the rear. Surprised,

the enemy regiment tried to withdraw, but the fast-moving South Vietnamese

force literally ran over it. A day-long, running battle left North Vietnamese

Army resistance shattered, the enemy in flight, and the field covered with

enemy casualties and abandoned weapons.

-

- While the U.S. 25th Infantry Division held the center of the potential envelopment,

a South Vietnamese task force moved north on 17 May to secure Route 15, halfway

to the besieged town of Kampong Cham. Other South Vietnamese task forces spread

out to secure the penetration, and Vietnamese district and province forces

moved in to perform the detailed search and evacuation of captured material.

On 9 May the 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, which had been securing

the line of communications to Tonle Cham in War Zone C, moved into Cambodia

to search the rubber plantations at Memot. The cavalrymen discovered a motor

park with twenty-one American-made 21/2-ton trucks of World War II vintage

that had been used in Korea (data plates were still on the vehicles) , rebuilt

in Japan, and sold as surplus. Once the batteries were replaced, the 1st Squadron

had its own truck convoy to haul captured equipment and supplies back into

South Vietnam.

-

- As operations in and around the Fishhook continued it became evident that

the free world forces had seriously underestimated the extent of enemy logistical

bases in Cambodia. Consequently, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was assigned

two engineer land clearing companies and along with the Vietnamese airborne

brigade began extensive Rome plow operations in the Fishhook. By late May

the southern Fishhook, which had become the most hotly contested portion of

TORN THANG 43, contained two squadrons of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment.

The monsoon had arrived, and movement became more difficult every day. As

June wore on the enemy became more persistent, and small daily fights were

a fact of life. Helicopters flying over the area habitually received ground

fire. Road-mining incidents and ambushes increased. None-

- [175]

- theless, the Rome plows cleared over 1,700 acres of jungle and destroyed

more than 1,100 enemy structures.

-

- In accordance with the presidential directive, plans were made to withdraw

U.S. forces from Cambodia by 30 June. The 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry,

moved along Highway 13 to Loc Ninh, while in the Fishhook the 1st and 3d Squadrons

departed through Katum. The 3d Squadron was ordered to remove the bridge sections

south of Snuol and to destroy the fire bases established along Route 7 near

Memot, a job made more difficult as the monsoon inundated the low ground,

leaving track vehicles virtually roadbound. With considerable difficulty the

bridges were removed or destroyed by the 3d Squadron as it withdrew. Captain

Ralph A. Mile's Troop L was the last U.S. armored unit to leave Cambodia.

-

- South Vietnamese Army Attacks Continue

-

- In late May, with the impending American withdrawal from Cambodia still

to come and the monsoon rains increasing, the South Vietnamese forces, unhindered

by the U.S. political decision, had continued attacking to complete the encirclement.

The Chup rubber plantation near Kainpong Cham was selected as the linkup point

for the converging task forces. The city, a key provincial capital strategically

located on the Mekong River, fifty kilometers northeast of Phnom Penh, was

besieged by the 9th North Vietnamese Division, which had its headquarters

in the plantation. The South Vietnamese objective was to attack the plantation

from the south and east, thus eliminating enemy pressure on Kampong Chain

and completely encircle the base areas.

-

- At 0730 on 23 May, a South Vietnamese armored task force passed through

the U.S. forces near Krek and ran head on into an entrenched rifle company

from the 272d Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Regiment, intent on stopping

any advance along Route 7. The enemy opened with rocket propelled grenade

and small arms fire on the lead tanks of the 5th Armored Cavalry Regiment,

which quickly formed on line and attacked. A short, fierce, close quarters

fight left most of the enemy dead or captured. The action was so fast that

units in the rear of the advancing column were unaware of the battle until

they passed the enemy dead along the road. Another South Vietnamese armored

task force moving north along Highway 15 on 25 May encountered an enemy battalion

at the Chup plantation. The 15th and 18th Armored Cavalry Regiments hit the

enemy positions from two sides, completely disorganizing the resistance. Fire

from the advancing tanks and armored cavalry assault vehicles left over 110

North Vietnamese dead. Three days

- [176]

- later in the southwestern part of the Chup plantation, another enemy battalion

was defeated in a six-hour action. The task forces joined on 29 May, breaking

the seige of Kampong Cham and surrounding the enemy base areas to the south.

-

- In mid-June, when the 9th North Vietnamese Division Teentered the Chup plantation,

again threatening Kampong Cham and Prey Veng, South Vietnamese units began

a new drive to clear the plantation and destroy the enemy division. For six

days an armor-heavy task force chased the enemy through the rubber plantation

and south along Route 15. Finally, the task force was attacked by the 271st

Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Regiment, which planned to cut the Toad and

isolate the task force. The next three days saw some of the heaviest fighting

of TOAN THANG 42. The enemy was well positioned,

but repeated attacks by the 15th and 18th Armored Cavalry Regiments prevented

his control of the road. Attacks by tanks and armored cavalry assault vehicles

with attached infantry and Rangers finally routed the North Vietnamese, and

by 29 June the fighting had ended. The final phase of the operation, 1-22

July, involved road security missions and search operations. No significant

fighting occurred, and all Military Region 3 units had left Cambodia by 22

,July 1970.6

-

- The South Vietnamese forces of Military Region 3 periodically returned to

Cambodia during the next eighteen months. Most of their operations were hit

and run, and had limited objectives and minor successes. One operation, TOAN

THANG 01-71, started with high hopes on 4 February 1971 and ended in disaster

four months later. Little was officially reported about this operation since

world attention was dramatically focused on LAM SON 719 to the north

in Laos, and no U.S. ground forces or advisers could be used in Cambodia.

Near the end of May a South Vietnamese task force was cut off in Cambodia

south of Snuol on Route 13. Although the commander had received intelligence

reports from South Vietnamese and U.S. sources, including visual aerial reconnaissance

from the 3d Squadron, 17th Cavalry (Air) , he failed to guard against a growing

enemy threat.7

-

- The 3d Armored Brigade was ordered north to link up with the isolated task

force on Route 13. After a misunderstanding of orders, during which the task

force at first refused to attempt to withdraw,

- [177]

- the task force troops attacked south toward the armored brigade, but intense

rocket, small arms, and machine gun fire quickly disorganized the attack.

Many infantrymen ran from exploding or disabled vehicles; others, trying to

hide from the deadly fire, climbed under or onto the vehicles. Some soldiers

already on the vehicles crawled inside for cover, while more and more attempted

to mount the moving vehicles to escape. As the column continued down the road

it became a rout.

-

- After two days of massive artillery, air cavalry, and tactical air strikes,

the armor brigade finally accomplished the linkup. The task force passed through

the brigade with each tracked vehicle carrying thirty to thirty-five infantrymen.

Both sides suffered heavily, but for the South Vietnamese forces command and

control again emerged as a serious problem. What had begun as an orderly withdrawal,

turned into a rout. The collapse of command under stress was to plague the

South Vietnamese forces to the end of the war.

-

- Secondary Attacks Across the Border

-

- In examining the final results of the expeditions into Cambodia, it is well

to note that two separate series of South Vietnamese operations supported

the TOAN THANG attacks. The first, Operation Cuu LONG I-III, from IV Corps

Tactical Zone, lasted from 9 May till 30 June 1970, and involved five armored

cavalry regiments as well as infantry, Rangers, elements of the Vietnamese

Navy, and units of the Regional Forces and Popular Forces. The operational

area was more than ninety kilometers wide and extended north to Phnom Penh.

The object was to secure the Mekong River as far north as the Cambodian capital

so that the Vietnamese refugees gathered in the city could be evacuated to

South Vietnam. The operation indirectly supported III Corps Tactical Zone

forces involved in Operation TOAN THANG 42.

-

- CUU LONG I began with an assault on locations along the Mekong by aircraft

of the U.S. 164th Aviation Group which formed the largest air armada ever

assembled in IV Corps Tactical Zone for a single operation. By 13 May linkup

had been accomplished with III Corps forces, and the Mekong River was secure

from the border to the capital of' Cambodia. Five hundred of the enemy were

killed. Forty ships passed safely up the Mekong to Phnom Penh, where they

evacuated over 12,000 Vietnamese civilians. Eventually, more than 40,000 Vietnamese

were evacuated through this safe corridor.

-

- Operations Cuu LONG Il and III, from 17 May to 30 June, were directed at

enemy forces and base camps in southeastern Cambodia. They were designed to

assist the Cambodians in constructing bases

- [178]

- and reestablishing local government. In both operations cavalry units traveled

rapidly for more than fifty kilometers to relieve besieged Cambodian garrisons,

and then turned their attention to searching for supplies. One cache discovered

by Troop D, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, yielded millions in National Liberation

Front money printed for use in South Vietnam after Tet 1968.

-

- The other series of operations into Cambodia originated in II Corps Tactical

Zone and was designed to support TOAN THANG 42 by drawing enemy units north

and cutting the enemy logistical lifeline north of the main battle. Operations

BINH TAY I-IV were conducted from Kontum in the north to Ban Me Thuot in the

south and were controlled and executed by the South Vietnamese Army.

-

- The first three phases of BINH TAY were directed against Base Areas 701,

702, and 740, long utilized to support Viet Cong and North Vietnamese units

operating in the central highlands of the II Corps area. There was little

activity by armored units during these operations; South Vietnamese commanders

preferred to use their armor for security and transportation. Enemy resistance

was light and poorly organized. These first phases, although successful, showed

clearly that the South Vietnamese commanders in II Corps Tactical Zone did

not fully appreciate the possibilities for maneuver and firepower that armored

units possessed. The II Corps cavalry regiments were not given the freedom

of action afforded similar units in the III and IV Corps areas.

-

- BINH TAY IV, conducted from 24 to 26 June, was the final II Corps operation

in Cambodia. It included the largest aggregation of armored forces in the

II Corps zone and, unlike other BINH TAY operations, was not directed toward

destruction of enemy forces or bases but toward the evacuation of Cambodian

and Vietnamese refugees. The armor spearhead, catching the enemy units off

guard, moved swiftly into Cambodia on 24 June and set up defensive positions

along the withdrawal routes. When the operation ended on 26 June 1970, over

8,500 Cambodians, more than 3,800 of them military, and over 200 vehicles

and much equipment had been removed from the danger of control by the Viet

Cong and North Vietnamese.

-

- Cambodia in Perspective

-

- By the end of June free world forces in Cambodia had captured or destroyed

almost ten thousand tons of materiel and food. In terms of enemy needs this

amount was enough rice to feed more than 25,000 troops a full ration for an

entire year; individual weapons to equip 55 full-strength battalions; crew-served

weapons to equip 33 full battalions; and mortar, rocket, and recoilless rifle

- [179]

- ammunition for more than 9,000 average attacks against free world units.

In all, 11,362 enemy soldiers were killed and over 2,000 captured.

-

- These statistics are impressive, and without a doubt the Cambodian expeditions

had crippled Viet Cong and North Vietnamese operations, but the most important

results cannot be measured in tangibles alone. The armored-led attacks into

Cambodia by units from Military Region 4 had been well planned, well coordinated,

and well carried out. They were generally conducted without the massive U.S.

ground support typical of operations by units from Military Region 3, yet

they severely hurt the enemy. The South Vietnamese, their morale high, returned

to resume pacification of the delta, a goal which had suddenly come much closer

to realization.

-

- In Military Region 3 the results of operations TOAN THANG 42 and 43 were

alo impressive, and had a great pyschological and material effect on the enemy.

Even more important, South Vietnamese forces had operated over great distances

for long periods without direct American assistance and often without advisers.

This fact provided a great boost to South Vietnamese morale and improved fighting

ability. The Vietnamese forces had temporarily strengthened the position of

the Cambodian government and brought some measure of order to its border provinces.

-

- On the other side of the ledger, the results of the last expedition from

Military Region 3 revealed the continued existence of command and control

problems among South Vietnamese commanders. To overcome timidity and lack

of coordination at high command levels, would, in the final analysis, be more

important than material gains.

-

- The lack of understanding of armored operations exhibited in Military Region

2 did not bode well for the future, although eventually new commanders there

would begin the process of correction. The boost given to the Cambodian government

and its army was only temporary, for the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces

returned and quickly took complete control of all the border areas.

-

- The most important effect of the operations in Cambodia must be looked for

within South Vietnam; here the attacks bought time for strengthening the Vietnamese

forces and for the United States to continue its withdrawals.8

For the next fourteen months there

- [180]

- were almost no Viet Cong and North Vietnamese operations in South Vietnam.

The Cambodian operations greatly increased the confidence of Vietnamese armored

forces in their ability to wage a successful and prolonged campaign. It was

the most convincing evidence since Tet 1968 of the improvement

of Vietnamese armored forces. The high morale of the South Vietnamese forces

convinced American advisers that the Vietnamese were well on their way to

being able to fight the war on their own.

-

- Maintenance and Supply

-

- One unusual feature of American operations in Cambodia was the American

policy that all vehicles and equipment, no matter how badly damaged-even if

beyond repair-had to be evacuated to Vietnam. While this ruling was made at

high levels for political, intelligence, and propaganda purposes, it calls

attention to a major problem that confronted armored units throughout the

war.

-

- In an armored unit, the soldier is as dependent on his armored vehicle as

the vehicle is on him. In few other combat units in the Army are maintenance

and the supporting supply system so critical. Most armored units found the

U.S. Army supply and maintenance system in Vietnam to be less than satisfactory

at every level. The deficiencies in the system were basic. As the war expanded

and mobility became more and more important the faults in the system became

more obvious.

-

- Two faults were apparent in the early years, and they eventually exposed

a third. The first was the lack of general support maintenance-heavy repair

facilities in the major areas where armored vehicles were used. This lack

was the result of the decisions of 1965 and 1966 to build up

combat troops at the expense of the logistical base. Although it was an expedient

meant for a short time, the decision was never really altered. Even more unfortunate

was the fact that in many cases the few support units that were available

were centralized in areas far from the combat units. The obvious solution

to this problem, the use of teams authorized to make major repairs at a unit's

location, however popular with units was not popular with logisticians. Thus,

combat units were frequently forced to send damaged vehicles great distances

for repair. In Military Region 3, vehicles were almost always sent back to

the Long Binh-Saigon-Cu Chi area, a distance of ninety or more kilometers

from the border and base areas where the fighting was. The resulting loss

in combat power and the drain on the meager evacuation resources of the combat

units was a severe hardship.

-

- In an attempt to solve this problem, Colonel Starry had forced

- [181]

- repair teams forward to squadron and troop level in the 11th Armored Cavalry

Regiment even before the invasion of Cambodia. To help with the critical problem

of evacuating materiel from Cambodia the 11th Cavalry borrowed six M88 tank

recovery vehicles from the depot at Long Binh. Organized into recovery platoons

operating with the 3d Squadron, these vehicles were invaluable to the regiment's

recovery operations.

-

- The second problem, the tendency of logistical units to stick to base camps,

was evident early in the war and continued to the end. Logistical units, particularly

supply and maintenance elements, were unprepared psychologically and in practice

to live in the field close to the units they supported. Although Army doctrine

stressed that this support should be provided in forward areas, the practice

was to centralize support facilities in built-up, well-developed, permanent

base camps, similar to installations in the United States. In Military Regions

2 and 3, this practice placed support facilities as close to the coast as

possible, often more than 100 kilometers from the fighting units, and accessible

only by means of tenuous supply and evacuation routes. While this placement

was easier for the supply and maintenance units, it was a hardship for the

combat units.

-

- The most critical problem was the unsatisfactory performance of the area

support system under combat conditions. It is amazing that the system was

expected to work in a war of movement, in which armored units traveled great

distances in short periods of time. In Vietnam, it was not the answer for

armored units, particularly armored cavalry regiments. According to Lieutenant

General Joseph A. M. Heiser, Jr., former commander of the 1st Logistical Command,

Vietnam, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment "obtained its maintenance

support from the 1st Logistical Command on an area basis. As elements of the

regiment relocated, the nearest 1st Logical Command unit provided service.

This method of support proved unsatisfactory because of the 11th ACR's high

and fluctuating maintenance demands. In the future such organizations should

be assigned an organic maintenance unit."

-

- While the problem was apparent in the 11th Armored Cavalry, it existed also

for the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) , in northern Military

Region 1. Although the mechanized brigade operated under control of the 3d

U.S. Marine Division, the marines were responsible for supplying only rations

and fuel. The 1st Brigade had its own organic supply and maintenance support

but relied for wholesale level supply on distant Army support units. Several

unanticipated maintenance difficulties developed as

- [182]

- a result of this extended logistical link. Operations in the sandy soil

of the northern coastal areas caused such excessive track and sprocket wear

that spare parts were frequently inadequate. To cope with the problem, special

brigade convoys were sent directly to the depots in an effort to shorten the

delivery time of parts. Nicknamed the Red Ball Express, these convoys eventually

eased many of the brigade maintenance problems.

-

- These were not isolated examples, for combined arms operations stressed

cross-attachment at battalion level, with the units often operating over great

distances for long periods of time. The 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, in Military

Region 3 had two companies detached for almost its entire time in the war-four

years. Maintenance support of these two companies remained the responsibility

of the battalion. Since one company was in northern Military Region 1, the

situation became ludicrous when the battalion executive officer had to search

the Saigon area for parts and then airlift them to the Hue area, 750 kilometers

north. The other company, in Military Region 3, was often split among three

locations, yet the battalion had to find and support them daily, even though

the company was attached to a different division. Since the battalion had

a limited resupply and maintenance system, this situation was completely unsatisfactory.

-

- In Military Region 2, elements of the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, and 1st

Battalion, 50th Infantry (Mechanized) were often attached to the 1st Air Cavalry

Division, yet the division had no means of repairing armored vehicles. With

the distant parent battalion still responsible for maintenance and logistical

support, the tank and mechanized companies frequently found themselves sorely

pressed for supplies and replacement parts. The 1st Cavalry Division was able

to repair equipment common to both the companies and the division; however,

if the equipment was not common, long resupply delays were normal. In an attempt

to partially solve the problem, Company A, 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, used

its organic vehicles to obtain repair parts directly from the Qui Nhon support

command.

-

- Examples of the failure of the rigidly structured area support system to

sustain adequately a constantly changing troop concentration are almost endless.

Support units requisitioned parts over a 9,600-mile supply line, with attendant

delays. There were never enough spare parts on hand to repair the armored

vehicles in any given area. When parts were ordered they often arrived after

the units had moved to a different support area, and the requisitioning process

had started again.

- [183]

- Many demands that could have been met by depots in Vietnam were not met

because the centralized inventory system broke down. Depots had spare parts,

some of them important items, of which they were not even aware. Thus was

born the system of searching for parts that the combat units called scrounging.

The scrounger, or expediter, was an individual or a team from the combat unit

sent to the major spare parts depot, usually in the Saigon area, to walk through

the storage areas in an attempt to locate spare parts. When an item was found,

it had to be formally released by supply control officials, often over the

protests of supply personnel who were positive they did not have the item-even

when it was physically pointed out. This fact was recognized by the Department

of the Army late in the conflict when projects such as Stop/See, Count, Condition,

and Clean were started in an attempt to verify inventories. One inventory

team was sent to Okinawa to open twenty-six acres of shipping containers for

which no inventory existed.

-

- In combat units, inexperienced crew members, supervisors (officers

and noncommissioned officers), and maintenance personnel contributed to the

problem. Parts were often requested and replaced unnecessarily. Such instances

became more apparent late in the war as a greater number of untrained people

were assigned to unit maintenance operations.9

Compounding this problem was the sometimes improper management of the

battalion parts system that led to inadequate records and failure to order

parts. In 1969 and 1970 the 11th Armored Cavalry was able to reduce its prescribed

load lists by about 75 percent, with a dramatic increase in operational readiness.

The supply system at the unit level was glutted with too much unneeded gear.

Nonetheless, Colonel Starry noted that his regiment was obliged to live off

its battle losses by cannibalizing disabled vehicles; the supply system provided

only half the regiment's needs, cannibalization the rest.

-

- The critical problem continued to be with the area support system. Although

commented upon in the 1967 report evaluating mechanized and armor combat operations

in Vietnam, a maintenance support unit dedicated primarily to the 11th Armored

Cavalry Regiment was not created until 1970, and then only after the regimental

commander had convinced officers at higher levels that such a measure was

necessary.

-

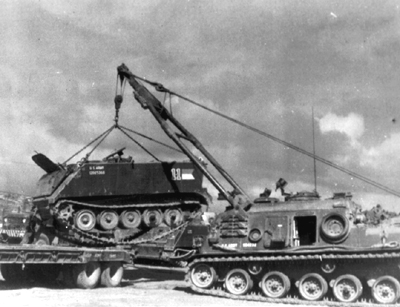

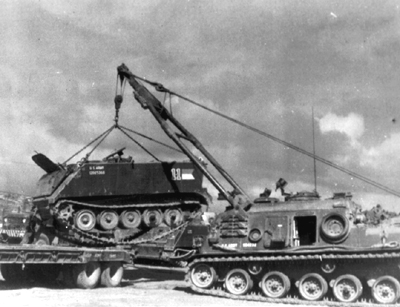

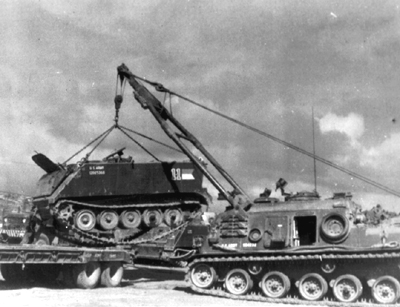

- Evacuation of damaged vehicles was another problem that

- [184]

-

M88 HEAVY RECOVERY VEHICLE LOADS DAMAGED APC, JANUARY

1971. This versatile vehicle was the workhorse of the armor recovery

fleet.

-

- plagued combat units. Before the Vietnam War the standard practice had been

to leave damaged vehicles at collecting points on the main supply route for

supporting units to dispose of. But in Vietnam no provision for such evacuation

was made, and the responsibility therefore fell entirely upon the combat units.

In Cambodia, for example, combat units evacuated all vehicles to Vietnam no

matter how badly damaged. The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment eventually devoted

more than one-third of its combat strength in Cambodia to this task.

-

- Recovery of damaged machines at the small unit level required considerable

ingenuity. Often the vehicles designed for recovery were inadequate, as in

the case of the M578, or were in short supply, like the M88. No unit ever

had these items in the numbers required, and there were never enough spare

parts to repair them on the spot. Because recovery vehicles were frequently

out of action for extended periods, awaiting parts, heavy reliance had to

be placed on the inventiveness of the small unit leader. In many cases the

performance of these leaders was brillant. Such recovery devices as the push-bar,

log extraction, "daisy chain," and block and tackle were field expedients.

-

- Many of the maintenance problems cited, particularly the attitude of the

support units, exist today and would create the same

- [185]

- difficulties in a war fought in Europe as they did in Vietnam. In view of

the renewed emphasis on mobile warfare and the heavy odds that armored forces

must face, a much more responsive supply and maintenance system is a necessity.

Forward location of maintenance units, forward support, mobile repair teams,

and quick resupply from accurate inventories must become as routine for combat

service support units as the use of combined arms for armored units.

-

- Lam Son 719

-

- After U.S. units withdrew from Cambodia in June of 1970, the face of the

war in Vietnam changed significantly. The remainder of the year was a time

of small and infrequent enemy infantry attacks, fire attacks, and chance engagements.

American forces directed their efforts toward strengthening the South Vietnamese

forces and pacification of the South Vietnamese people. Mainly because of

the Cambodian incursions and the resulting disruption of the enemy's supply

and training bases, both causes advanced rapidly.

-

- American forces were relocated in bases farther

from the border, and the South Vietnamese Army assumed responsibility for

the security of the border.10

For the first time in many years, the South Vietnamese had to shoulder the

larger share of combat operations- a dramatic change. South Vietnamese

forces moved toward self-sufficiency and achieved considerable success. Regional

Forces and Popular Forces took over many of those defensive operations that

had long tied down the Vietnamese Army. And as U.S. troops were withdrawn

from Vietnam, South Vietnamese units began large-scale operations on their

own.

-

- By late 1971, after extensive destruction of enemy supplies during the Cambodian

incursions, enemy logistical and troop movements along the Laotian trails

in the north increased dramatically. This fact and the impending withdrawal

of U.S. air support prompted the South Vietnamese Army to attack into Laos

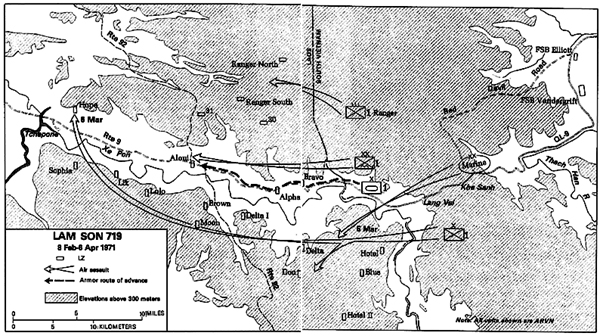

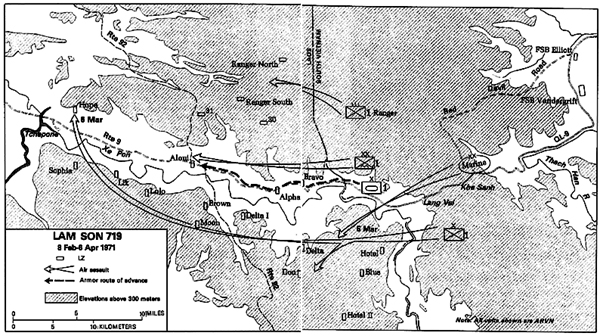

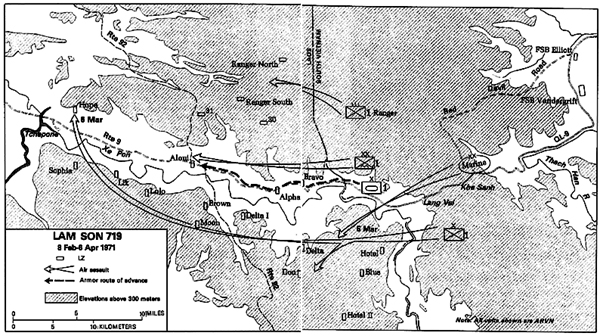

and strike the enemy trail network at a junction near Tchepone. (Map 15)

The South Vietnamese planned to commit two reinforced army divisions and

their Marine division to this operation, LAM Sort 719, commencing early in

1971. The planners considered this attack the last chance for cross-border

operations using U.S. air support. They also believed that the operation,

if successful, could

- [186]

- prevent a major enemy offensive for at least another year and take some

pressure off the Cambodian Army to the south.

-

- LAM SON 719 demonstrated what can happen when a large operation is insufficiently

coordinated: conflicting orders were issued, the limited amount of armor was

misused, unit leadership broke down, and the strength of the enemy was either

overlooked or disregarded. That the North Vietnamese knew of the attack beforehand

was evident in their placement of artillery, mortars, and antiaircraft weapons

in the area of operations chosen by the South Vietnamese. Enemy troop buildups

north of the Demilitarized Zone were noted as well as an increase in the movement

of supplies along the trails.

-

- Although American ground forces supported LAM SON 719, they were required

to remain in South Vietnam. A task force, part of Operation DEWEY CANYON II,

consisting of elements of the 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry (Mechanized)

,11

the 1st Battalion, 77th Armor, the 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, and Troop A,

4th Squadron, 12th Cavalry, had the mission of establishing logistical bases,

keeping Route QL-9 open to the Laotian border, and covering the withdrawal

of the South Vietnamese.

-

- At 0400 on 29 January the task force left Quang Tri City along National

Highway 9 and by nightfall rolled into Fire Support Base Vandergrift. After

a short halt Troop A, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, commanded by Captain Thomas

Stewart, and two engineer companies led out on foot at midnight on 29 January.

The vehicles were left to move with the main body since Route 9 was known

to be in a poor state of repair. A bulldozer led the column with headlights

blazing.12

Whenever an obstacle such as a damaged bridge was encountered, a force of

two to six cavalrymen and engineers would stop to make repairs while the rest

of the team continued. The cavalry troop, joined by its vehicles, arrived

at Khe Sanh at 1400 on 1 February, with National Highway 9 opened behind it

from Fire Support Base Vandergrift. The next day the road was opened all the

way to the border by the 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry (-) .

-

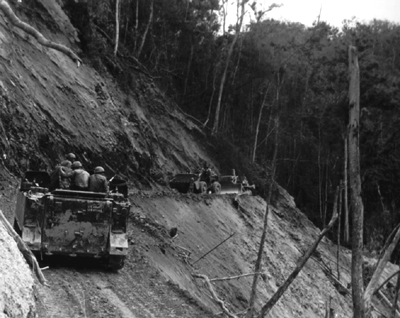

- As a supplement to this route, the remainder of the 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry,

and elements of the 7th Engineer Battalion con-

- [187]

- MAP 15

- [188-189]

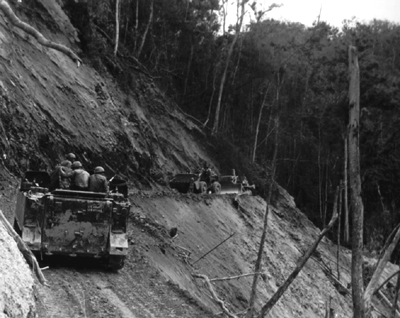

- RED DEVIL ROAD, an engineering feat that opened enemy areas never before

penetrated.

-

- structed a secondary road, known as Red Devil Road and roughly parallel

to Route 9, from Fire Support Base Elliott to Khe Sanh. The 3d Squadron, 5th

Cavalry, continued operations north of Khe Sanh along Red Devil Road until

7 April.

-

- The South Vietnamese Army Attack

-

- In LAM SON 719, the Vietnamese hoped to disrupt Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

supply lines by a combination of airmobile and armor ground attacks on three

axes westward into Laos. The main attack was to be conducted along National

Highway 9 to Aloui by the airborne division and the 1st Armored Brigade, which

would then continue west on order. The South Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division,

in a series of battalion-size airmobile assaults, was to establish fire bases

on the high ground south of Route 9 to secure the south flank. The South Vietnamese

1st Ranger Group was to conduct airmobile assaults to establish blocking positions

and secure the north flank. The Vietnamese Marine division was the I Corps

reserve at Khe Sanh. The U.S. 2d Squadron, 17th Cav-

- [190]

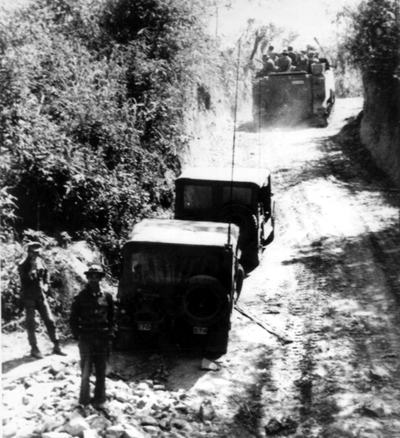

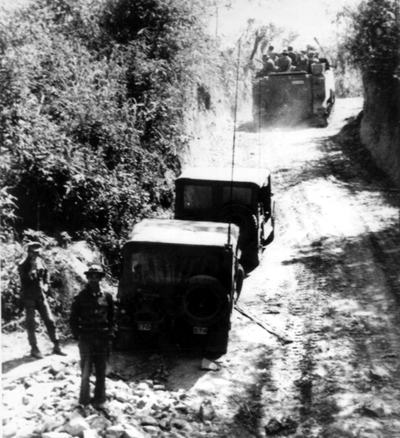

- ACAV's OF SOUTH VIETNAMESE 1ST ARMORED BRIGADE ON ROUTE 9 IN LAOS, 1971

-

- alry, was to locate and destroy antiaircraft weapons, find enemy concentrations,

and carry out reconnaissance and security missions, which included the rescue

of air crews downed in Laos. The squadron was permitted to go into Laos only

one hour before the first airmobile assaults. This constraint precluded early

reconnaissance of North Vietnamese antiaircraft positions, and in the beginning

limited the air cavalry to screening the landing zones just before the assaults.

-

- The 1st Armor Brigade, with two South Vietnamese airborne battalions and

the 11th and 17th Cavalry Regiments, which had fewer than seventeen M41 tanks,

crossed the border at 1000 on 8 February and moved nine kilometers west along

National Highway 9. Intelligence reports had indicated that the terrain along

Route 9 in Laos was favorable for armored vehicles. In reality, Route 9 was

a neglected forty-year-old, single-lane road, with high shoulders on both

sides and no maneuver room. Moreover, as the units moved forward they discovered

the entire area was filled with huge bomb craters, undetected earlier because

of dense grass and bamboo. Armored vehicles were therefore restricted to the

road.

-

- With armored units moving west on Route 9, the airborne division and the

1st Infantry Division made an assault into landing zones north and south of

Route 9. One Ranger battalion came down near Landing Zone Ranger South. As

the first troops arrived the air cavalry moved out to reconnoiter the front

and flanks, seek-

- [191]

- ing landing areas and destroying antiaircraft positions. But the demand

for gunships became heavy as units on the ground encountered North Vietnamese

Army forces. In the air cavalry, emphasis shifted to locating enemy troop

concentrations and indirect fire weapons that posed an immediate threat to

South Vietnamese forces. Thus, long-range reconnaissance was sacrificed for

fire support.

-

- The air cavalry screened the 1st Armor Brigade's advance along Route 9 all

the way to Aloui, which the brigade reached in the afternoon of 10 February.13

Within three days Vietnamese airmobile forces on the ridgelines to the north

and south had moved abreast of Aloui. Since the airborne division was unable

to secure Route 9; the 1st Armor Brigade as well as other ground forces had

to be resupplied by air for the duration of LAM SON 719.

-

- Enemy reaction to LANs SON 719 was swift and violent. The North Vietnamese

had elements of three infantry regiments as well as an artillery regiment

and a tank battalion in the area, and quickly brought in eight more infantry

regiments and part of a tank regiment. The north flank of the South Vietnamese

attack soon came under heavy assault. The Ranger battalion at Landing Zone

Ranger North was attacked on 20 February, and elements of the battalion withdraw

to Landing Zone Ranger South the next day. In the following days both Ranger

South and Landing Zone 31 came under increasing pressure until, on 25 February,

the Rangers were evacuated from Ranger South.

-

- As the South Vietnamese command debated whether to continue the drive west,

pressure on Landing Zone 31 developed into a coordinated enemy tank-infantry

attack with supporting fire from artillery and rockets. Command confusion

added to the problems of the Vietnamese forces when conflicting orders from

the airborne division and from I Corps headquarters delayed relief of the

landing zone by the armored brigade. On 18 February I Corps ordered the 17th

Armored Cavalry (-) north from Aloui to reinforce Landing Zone 31. At the

same time the airborne division ordered it to stop south of the landing zone

and wait to see if the site was overrun. Neither headquarters was on the scene.

AS a result of the confusion, the 17th Armored Cavalry, with tanks from the

11th Armored Cavalry, arrived at Landing Zone 31 on 19 February after some

airborne elements had been pushed back.

-

- In the first battle between North Vietnamese and South Viet-

- [192]

- namese tanks, Sergeant Nguyen Xuan Mai, a tank commander in the 1st Squadron,

11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, destroyed a North Vietnamese T54 tank.14

The South Vietnamese forces retook a portion of the landing zone by the end

of the day. Twenty-two enemy tanks-six T54's and sixteen PT76's-were destroyed,

with none of the South Vietnamese M41's lost. Direct and indirect fire continued

to pound the airborne troops, and, finally, after six days, the enemy overran

the entire landing zone. The 17th Armored Cavalry Regiment and one airborne

battalion were pushed to the south.

-

- After Landing Zone 31 was lost, all airborne elements were withdrawn and

the 17th Armored Cavalry was isolated southeast of the site. Enemy pressure

on the cavalry remained heavy. Attacked at noon on 27 February the cavalry,

supported by tactical air and cavalry helicopter gunships, reported destroying

fifteen tanks twelve PT76's and three T54's-and losing three armored cavalry

assault vehicles. Later, on 1 March, still southeast of Landing Zone 31, the

cavalry was attacked again. In this battle, which lasted throughout the night,

the cavalry was supported by South Vietnamese artillery, U.S. tactical air

strikes, and cavalry gunships. Fifteen enemy tanks were destroyed; the cavalry

lost six armored cavalry assault vehicles.

-

- Despite recommendations from the American adviser of the 1st Armor Brigade

and the acting adviser of the division, the commander of the airborne division

failed either to support the 17th Armored Cavalry or to withdraw it. On 3

March, after the cavalry was surrounded on three sides by enemy armor and

its route of withdrawal was blocked by direct tank gunfire, the South Vietnamese

Chief of Armor, with the approval of the I Corps commander, intervened by

radio. He obtained air support from I Corps and ordered the 17th Cavalry south

to more defensible ground. From there, the cavalry subsequently fought a delaying

action and rejoined the 1st Brigade at Aloui.

-

- Air Cavalry and Tanks

-

- Fortunately for Operation LAM SON 719, the confusion on the ground did not

extend to the air cavalry. The performance of the air cavalry remains one

of the outstanding achievements of the operation, particularly since it operated

in the most hostile air environment of the war. All air cavalry in Laos was

controlled by

- [193]

- the U.S. 2d Squadron, 17th Air Cavalry, which reported directly to the U.S.

XXIV Corps. In addition, the cavalry had operational control of the reconnaissance

company of the South Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division. Called the Black Panthers,

or Hac Bao, the unit was an elite, 300-man company, cross-trained and organized

into aerorifle platoons, and used for ground operations in Laos.

-

- The greatest threat to air cavalry was fire from .51-caliber machine guns,

which the North Vietnamese Army employed in large numbers, locating them in

mutually supporting positions. The OH-6A scout helicopter was too vulnerable

to heavy fire from these guns to operate as part of the reconnaissance team.

Instead, groups of two to six AH-1G Cobras and one command and control aircraft

were formed, with scout pilots as front seat gunners in the Cobras. Although

not designed as a scout ship, the Cobra did well in the reconnaissance role.

Its weapons could immediately engage the enemy and it was powerful enough

to make runs at high speed through hostile areas without taking unacceptable

risks.

-

- When the squadron encountered tanks for the first time, high explosive antitank

(HEAT) rockets were not available, and it used whatever ordnance was on board.

The Cobra gunships opened fire at maximum range, using 2.75-inch flechette

rockets to eliminate enemy troops riding on the outside of the tank and to

force the crew to close the hatches. As the gun run continued, high-explosive

and white phosphorus rockets and 20-mm. cannon fire were used against the

tank itself.

-

- Eventually HEAT rockets became available, but they were not always effective.

Although these rockets were capable of penetrating armorplate, they could

do so only in direct hits. Engagements therefore had to take place at ranges

of 900 to 1,200 meters, distances that exposed the gunship to the tank's heavy

machine gun and to supporting infantry weapons. Between 8 February and 24

March, air cavalry teams sighted 66 tanks, destroyed 6, and immobilized 8.

Most of the tanks, however, were turned over to fixed wing aircraft, which

could attack with heavier ordnance.

-

- The Withdrawal

-

- After the 17th Armored Cavalry withdrew from Landing Zone 31 and returned,

the 1st Armor Brigade task force continued to occupy bases near Aloui. Again

because of conflicting orders from the airborne division and I Corps headquarters,

the brigade did not move farther west and therefore became a target for intense

enemy fire; losses in men and equipment mounted. Eventually a point was reached

when the 1st Armor Brigade could not, if it had been

- [194]

- ordered, move west of Aloui. As a result, the 1st Infantry Division was

ordered to seize Tchepone, and did so on 6 March with an airmobile assault

into Landing Zone Hope.

-

- By early March enemy forces in the LAM SON 719 area had increased to five

divisions: 12 infantry regiments, 2 tank battalions, an artillery regiment,

and at least 19 antiaircraft battalions. After encountering enemy armored

vehicles at Landing Zone 31, South Vietnamese planners had realized that North

Vietnamese armor was present in strength, and the 1st Armor Brigade was strengthened

with additional units as they became available. The reinforcement was so piecemeal

and the troops came from so many different units, however, that it was difficult

to tell just who or what was committed. Many units never reached Aloui and

merely became part of the withdrawal problem. Even with all the detachments,

attachments, additions, and deletions, only one-third of the cavalry squadrons

and two-thirds of the tank squadrons available to I Corps were used in Laos.

Numerically, this employment amounted to five tank squadrons and six armored

cavalry squadrons.

-

- Faced with superior enemy forces, the I Corps commander decided to withdraw.

Although units attempted to evacuate the landing zones in an orderely fashion,

constant enemy pressure caused several of the sites to be abandoned and forced

the defenders to make their way overland to more secure pickup zones. Several

units had considerable difficulty breaking away from the pursuing enemy and

were lifted out only after intense tactical air, artillery, and aerial rocket

preparation.15

By 21 March the 1st Infantry Division had completely withdrawn from Laos and

major elements of the airborne division had been lifted out.

-

- The I Corps commander ordered the 1st Armor Brigade to withdraw on 19 March.

He further allocated two U.S. air cavalry troops to the airborne division

to cover the move. With the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment as rear guard the

1st Armor Brigade began its withdrawal on time, but the brigade received no

air cavalry support. Both troops had been diverted by the airborne division

to support airborne battalions elsewhere.

-

- At a stream crossing halfway between Aloui and Landing Zone Alpha, the armored

column was ambushed by a large North Vietnamese force. The unit in front of

the 11th Armored Cavalry abandoned four M41 tanks in the middle of the stream,

where they

- [195]

- completely blocked the withdrawal route. The airborne infantrymen refused

to stay with the cavalry and continued east down the road. The armor brigade

commander was informed of the situation but sent no reinforcements or recovery

vehicles to clear the crossing. Troopers of the 11th continued to fight alone,

and after three hours succeeded in moving two of the abandoned tanks out of

the way. The cavalry then crossed, leaving seventeen disabled vehicles to

the west of the stream. The North Vietnamese immediately manned the abandoned

vehicles, which they used as machine gun positions until tactical air strikes

destroyed them on 25 March. What had begun as an orderly withdrawal was rapidly

becoming a rout.

-

- The armor brigade reached Landing Zone Alpha on 20 March, regrouped, and

pushed on, still without benefit of air cavalry. The next morning the brigade,

with the 11th Armored Cavalry leading, was again ambushed, this time three

kilometers east of Fire Support Base Bravo. In the midst of the firefight,

an air strike accidentally hit the Vietnamese column with napalm, killing

twelve and wounding seventy-five. The brigade withdrew west to regroup.

-

- By that time the armor brigade had lost approximately 60 percent of its

vehicles, and when a prisoner reported that two North Vietnamese regiments

were waiting farther east along Route 9 to destroy it the armored force turned

south off the road. The airborne division, also aware of the prisoner's statement,

had meanwhile airlifted troops north of Route 9 and cleared the ambush site.

The armor brigade, unaware of the airborne action, found a marginal crossing

over the Pon River, two kilometers south of Route 9. The brigade recrossed

the river twelve kilometers to the east and reached Vietnam through the positions

of the 1st Battalion, 77th Armor.

-

- The withdrawal of the 1st Armor Brigade is perhaps the most graphic example

of the poor coordination between major commands throughout LAM SON 719. When

the brigade left Route 9, less than 5 kilometers from Vietnam via road, it

was forced to make two river crossings because its commander was not told

that the road had been cleared. It was this lack of coordination at the highest

levels, and the apparent lack of concern for the armored forces, that contributed

to the poor performance of armor.

-

- In Operation LAM SON 719, which officially ended on 6 April 1971, South

Vietnamese armor did not appear to advantage. In a static role at Aloui, armor

proved no more dynamic than a pillbox, and became a liability requiring additional

forces for its security. Command and control problems at all levels were evident,

and

- [196]

- plagued the operation from the start. A small amount of armor was committed

at first, and reinforcement was piecemeal. None of this, however, excused

the performance of some armored units which, especially during the withdrawal,

simply abandoned operational vehicles in their haste to get back to safety.

-

- Some good did come from LAM SON 719. For example, it helped to delay major

enemy operations for the remainder of 1971. The intelligence gained concerning

the North Vietnamese pipeline and trail network in Laos was used for planning

future bombing raids.16

The operation allowed the South Vietnamese forces to use U.S. aviation and

artillery support without the assistance of American advisers, and thus paved

the way for the South Vietnamese Army's complete operational control of U.S.

aviation and artillery in midsummer of 1971.

-

- Before this operation, the South Vietnamese infantry had little or no antitank

training, but the presence of enemy armor during LAM SON 719 led to greater

emphasis on antiarmor techniques and instruction in the use of the M72 light

antitank weapon. Both sides in LAM SON 719 lost heavily in men and equipment

and there was no clearcut victory, but psychologically the Vietnamese armored

forces had received a hard blow.

-

- Cuu Long 44-02

-

- One other South Vietnamese armored operation in 1971 was significant, although

it was not widely publicized. For one reason, since it occurred at almost

the same time as LAM SON 719, it was lost in the glare of reporting that operation.

For another, penetration into Cambodia, the deepest of the war, made it politically

sensitive. The operation was staged because the North Vietnamese had cut Route

4, the only supply road in Cambodia between Phnom Penh, the capital, and the

port of Kampong Som; the Cambodian government had requested South Vietnamese

assistance in reopening it.

-

- Operation Cuu Lorry 44-02 began on 13 January 1971, as the 4th Armor Brigade

with the 12th and 16th Armored Cavalry Regiments, three Ranger battalions,

an artillery battalion, and an engineer group, moved 300 kilometers from Can

Tho to Ha Tien in fourteen hours. For the next two days, the brigade pushed

north along Routes 3 and 4. The first enemy encountered had set up an

- [197]

- ambush that the 16th Armored Cavalry Regiment literally blew away by charging

on line.

-

- A second ambush farther north against the 12th Armored Cavalry also failed.

The enemy tried to isolate the lead squadron by destroying the first and last

vehicles. The lead commander, however, kept his flaming vehicle moving and

his machine gun firing. Hit three times and burning, the armored cavalry vehicle

continued north for about 150 meters before it blew up, killing the crew.

This heroic effort prevented the column from being trapped on the road and

allowed the cavalry to get out of the enemy firing lanes. The Ranger battalion

behind the cavalry squadron stopped and opened fire. The ambushers were now

in a deadly cross-fire between the cavalry and the Rangers. Two U.S. aerial

fire teams sealed off the enemy escape routes.17

When the smoke cleared, 200 of the enemy lay dead, and seventy-five weapons,

including two 75-mm. recoilless rifles and three heavy machine guns, had been

captured. The 12th Armored Cavalry Regiment lost five killed, twenty wounded,

and three tracks destroyed.

-

- On 17 January Cambodian forces, with Vietnamese Marine Corps support, fought

to the outskirts of the Pich Nil Pass and secured it, while the armor brigade

secured Route 4 as far north as Route 18. After helping the Cambodians set

up strongpoints, the 4th Armor Brigade withdrew toward South Vietnam, arriving

by 25 January.

-

- On several occasions, Vietnamese armored units had conducted bold operations

deep into enemy territory, in both Laos and Cambodia. Three major operations,

Cuu LONG 44-02, LAM SON 719, and TORN THANG 01-71, all took place simultaneously,

with the South Vietnamese hoping to keep the initiative gained in 1970. Of

the three operations, only Cuu LONG 44-02 can be regarded as a success, and

as a result Military Region 4 remained one of the most secure areas in South

Vietnam. The other two operations demonstrated that a parity existed in South

Vietnamese-North Vietnamese strength. The year 1971 was not successful for

either side; it ended with the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese as strong, if

not stronger, than the South Vietnamese.

- [198]

- Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-