- Chapter VIII:

-

- The Enemy Spring Offensive of

1972

-

- The largest military operation of 1970-1971 in Vietnam was not a combat

operation but the redeployment of over 300,000 American troops. Although the

withdrawal was governed to some extent by the fluctuating intensity of combat

operations, it moved as relentlessly as an avalanche. Of the 543,000 American

troops in Vietnam in April 1969, 60,000 had left by the end of that year.

In accordance with the planning guidance of General Abrams, only a few small

armored units were among those withdrawn.

-

- In 1970, when 139,000 American troops-including the first armored battalions

redeployed-returned to the United States, the concentration of U.S. armored

battalions climbed to forty-six percent of the combat units that remained

in Vietnam. The pace of the withdrawal slowed considerably during the Cambodian

expeditions but after August 1970, when U.S. operations in Cambodia ended,

large numbers of units were withdrawn. The highest percentage of armored units

leaving Vietnam came from Military Region 2, where enemy activity was almost

negligible. By the end of 1970, the 1st Squadron, 10th Cavalry, was the only

armored unit left in the region. The primary mission of this unit was still

road security.

-

- As the number of American troops in Vietnam decreased, the Army of the Republic

of Vietnam became the dominant force and began to assume operational control

of U.S. units. One such American unit was the 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry

Regiment. Late in April 1971 increasing enemy resistance to Rome plow operations

along Route 1, northwest of Saigon, made it plain that mechanized forces would

be needed if the project was to proceed on schedule. Accordingly, the security

of the entire Rome plow operation in Hau Nghia Province was placed under the

control of the 2d Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry, which reported directly

to the Vietnamese province headquarters.

-

- Throughout 1971 however, withdrawal was the U.S. mission, and 177,000, or

53 percent, of the Americans departed. By year's end, troop strength was 158,000,

the lowest since 1965. Fifty-four percent, of the remaining U.S. combat battalions

were armored units-four air cavalry and two armored cavalry squadrons as well

as many separate ground and air cavalry troops. Armored units

- [199]

- slated for redeployment were withdrawn from various parts of the country

during 1971, leaving armored strength evenly distributed from north to south.

-

- A lull in the Vietnam conflict during the first months of 1972, as U.S.

forces continued to disengage, was encouraging. Of all American units remaining

in Vietnam, only air and ground cavalry, performing reconnaissance and security

missions, continued to encounter the enemy with any degree of frequency. The

immediate effect of the withdrawal schedule was that most units were relegated

to administrative status, or, at best, to a local security role. While definite

restrictions limited the nature and scope of American participation in ground

combat, air cavalry units were under less restraint. U.S. air cavalry continued

to perform its reconnaissance and security missions with little regard for

the departure of other U.S. organizations.

-

- All American armored and air cavalry squadrons still in Vietnam at the end

of 1971 were ordered to redeploy before 30 April 1972. The last U.S. ground

cavalry unit to conduct operations was Troop F, 17th Cavalry, which left Da

Nang on 6 April. The 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry, which began its return on

10 April, was the last ground cavalry unit to leave Vietnam. Troop D, the

1st Squadron's organic air cavalry troop, was redesignated Troop D, 17th Cavalry,

and assigned to Da Nang. It remained in Vietnam until after the cease fire

and supported the Army of the Republic of Vietnam ground units in Military

Region 1.

-

- As the air cavalry squadrons departed, they left behind separate air cavalry

troops as the last vestige of U.S. combat strength. Thus, Troop C, 16th Cavalry,

was the sole air cavalry unit in Military Region 4. When the 7th Squadron,

17th Cavalry, left on 29 April -the last air cavalry squadron to redeploy

from Vietnam- it left behind two separate air cavalry troops, Troop H, 10th

Cavalry, and Troop H, 17th Cavalry. These two troops operated in Military

Region 2 until 25 February 1973 and were the last U.S. combat units to leave

Vietnam. Air cavalry units with the primary mission of supporting South Vietnamese

Army forces were the only active Army combat units in Vietnam in 1972.

-

- Point and Counterpoint

-

- The Vietnamese lunar New Year which began in February 1972 was the Year

of the Rat. Like the rat, the enemy assumed a low profile during the first

weeks of 1972. By day enemy forces avoided direct confrontation with free

world forces, and by furtive scurry-

- [200]

- ing at night built up extensive hoards of supplies and equipment in border

staging areas.

-

- As early as November 1971, the intelligence community, the government of

South Vietnam, and U.S. and South Vietnamese Army commanders anticipated a

significant enemy offensive in 1972, expecting the main effort to be made

in mid-February. The military objectives of the offensive were not known,

but intelligence sources reported that its goal would be the destruction of

the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Not even at the highest levels of government,

however, was a major shift in enemy tactics expected.

-

- That the North Vietnamese were capable of a large-scale offensive equal

to the Tet attack of 1968 was apparent. The possibility that enemy armor would

be a threat was considered insignificant, however, since only three times

during the Vietnam War had the North Vietnamese Army employed armored vehicles

in combat. Tanks in the North Vietnam inventory were estimated at more than

300, and were thought to be organized in three regiments. Two regiments were

known to be operating in Laos and Cambodia, where intelligence reports indicated

that they would remain.1

A report prepared by Headquarters, U.S. Army, Pacific, in February 1972, surmised

that terrain, logistics, and free world firepower would limit the size and

general location of armor-supported assaults. Sustained operations with tank

units larger than a company were considered impossible without establishment

of large fuel and supply caches in the border areas. The activity required

to establish these stockpiles would reveal enemy intentions and subject the

forces and supplies to devastating air attacks.

-

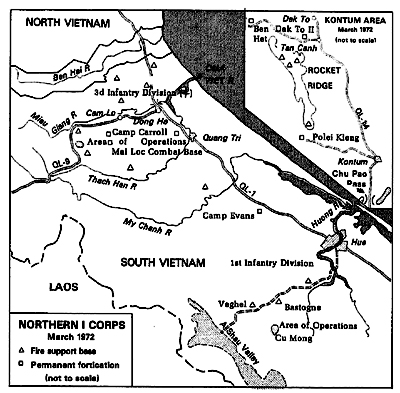

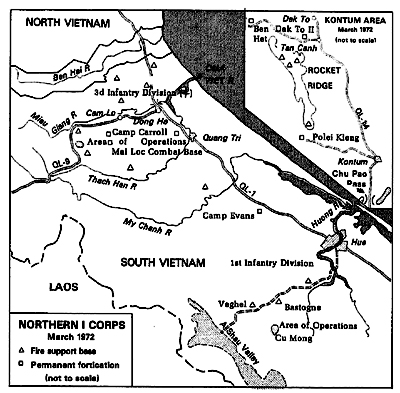

- In early March enemy offensive action in Military Regions 1 and 2 increased

and involved larger units. Continuing intelligence from sensors and other

sources in the northern part of Military Region 1 focused attention on the

A Shau valley, where free world forces had not operated since 1970. (Map

16) Road construction, enemy logistical troops, heavy artillery, antiaircraft

weapons, and tanks were detected with increasing frequency. The extent and

intensity of antiaircraft fire almost halted our air reconnaissance in the

mountainous areas west of Fire Support Base Bastogne. The South Vietnamese

1st Infantry Division looked on this buildup as a threat to Hue, and on 5

March started an operation called

- [201]

- MAP 16

-

- LAM SON 45-72 to destroy a logistical base near Cu Mong Mountain.

-

- Deliberately launched before the end of the wet season, this major undertaking

was planned as a joint airmobile and ground attack, but overwhelming antiaircraft

quickly compelled the South Vietnamese Army to advance only on the ground.

Heavy fighting took place early, and casualties from intense artillery fire

and daily B-52 bomber strikes forced the North Vietnamese Army to commit major

reinforcements from the 324E Division. A thrust by the 7th Armored Cavalry

Regiment and an infantry regiment in the vicinity of Fire Support Base Veghel

stirred up a hornet's nest. In the ensuing struggle the armored cavalry lost

two troops. The extent and ferocity of the fighting convinced the South Vietnamese

that the enemy intended to attack Hue in force. Pulling back to more favorable

terrain near the Bastogne base, South Vietnamese

- [202]

- soldiers fought continuously with North Vietnamese units well into May.

-

- In Military Region 2 reports on enemy tank sightings in the border areas

persisted but remained unconfirmed. During March the Air Force destroyed significant

qualities of stockpiled enemy supplies detected by the American air cavalry.

South Vietnamese cavalry units continued to perform route security missions

but otherwise staged no offensive operations.

-

- The 20th Tank Regiment

-

- Northern Military Region 1, a critical area bordered by North Vietnam and

Laos, was protected in the summer of 1971 by South Vietnamese infantry, three

South Vietnamese armored cavalry squadrons, and the U.S. 1st Brigade, 5th

Infantry Division (Mechanized), scheduled to leave the country in August.2

Analysis of terrain, the probable enemy threat, and enemy armored

actions during LAM SON 719 made it clear that armored units would continue

to be needed in this area. Consequently, the Vietnamese Joint General Staff

authorized on 31 July 1971 the formation of the 20th Tank Regiment. Equipped

with M48A3 tanks, it was the first South Vietnamese tank regiment

-

- Tailored specifically to fit the needs and capabilities of the South Vietnamese

Army, the 20th Tank Regiment had an unusual organization. During LAM SON 719,

armored vehicles had proven vulnerable to individual antitank weapons when

not protected by infantry. The Joint General Staff had therefore directed

an addition to the regiment, a 270-man armored rifle company. Ninety riflemen

were assigned to each tank squadron and were to ride on the outside of the

tanks, providing local security.

-

- Other changes in the tank regiment's organization and equipment included

the addition of tracked M548 ammunition and fuel cargo vehicles, elimination

of the regimental scout platoon, for which a five-vehicle security section

was substituted, and elimination of the armored vehicle-launched bridge section

and all infrared fire control equipment. Later six xenon searchlights per

squadron were authorized after advisers questioned the wisdom of limiting

$15 million worth of fighting equipment to daytime use by refusing

- [203]

- to spend $300,000 on searchlights. Unfortunately, the decision to dispense

with the vehicle-launched bridge section was not reconsidered, and lack of

bridging during the enemy offensive proved a major factor in the loss of tanks.

-

- Training for the 20th Regiment began at Ai Tu near Quang Tri City, but proceeded

slowly because of many problems, particularly in maintenance. About 60 percent

of the tanks received by the regiment had serious deficiencies beyond the

repair capability of the tank crews. Repair parts and technical manuals were

missing and the language barrier prevented U.S. instructors from communicating

adequately with the Vietnamese crewmen.

-

- On 1 November a gunnery program based on U.S. tank standards got under way.

Unfortunately, the inexperienced tank crews had difficulty in comprehending

the integrated functioning of the rangefinder and ballistic computer. In fact

the Vietnamese language could come no closer to the term ballistic computer

than to translate it "adding machine." Partly because of their experience

with the M41 tank, which had no rangefinder, Vietnamese commanders at first

could not be convinced of the rangefinder's value. Rapid troop turnover and

manpower shortages also adversely affected crew performance. Training therefore

made slow headway, with many reversions to basic lessons. By 25 .January gunnery

training ended, with 41 of 51 available crews qualifying, using test criteria

as rigorous as those used for U.S. units.

-

- Unit tactical training began in the foothills west of Quang Tri City on

1 February and was judged successful in its later stages. A recurring problem

during tactical testing was the Vietnamese inclination to disregard maintenance

before, during, and after an operation. Continued emphasis on maintenance

resulted in some improvement, but standards remained below acceptable levels,

even after the unit completed its training.

-

- The regiment's final tactical test, a field training exercise, was to be

conducted by the South Vietnamese Armor Command along U.S. lines, with the

proviso that any portion not completed correctly was to be repeated. Several

problems delayed the exercise past its scheduled starting date of 13 March.

Poor weather during the gunnery phase, the necessity for some tactical retraining

at the troop level, and the lack of M88 recovery vehicles and M548 tracked

cargo vehicles to carry fuel combined to cause setbacks. Finally, after devoting

several days to vehicle maintenance, the regiment began its training test

on 27 March. Within a few days the exercise was transformed into the ultimate

test-survival on the field of battle.

- [204]

- Attach Across the Demilitarized Zone

-

- By the end of March 1972, South Vietnamese defenses in Military Region 1

were arranged in a roughly crescent-shaped pattern of fire support bases in

northern Quang Tri Province, with the majority of forces oriented to the north

and west in the vicinity of the Demilitarized Zone. (See Map 16.) To the

south and stretching westward to Highway 1 from the sea were a number of small

Regional Forces outposts commanded by province and district chiefs. From Highway

QL-1 west and south, roughly paralleling the mountains, was the newly formed

South Vietnamese 3d Infantry Division, bolstered in the west by the Vietnamese

Marine division. Deployed with the regiments of the 3d Infantry Division was

its organic cavalry, the 11th Armored Cavalry. Farther to the south, guarding

exits from the A Shau valley and the approaches to Hue, was the South Vietnamese

1st Infantry Division with its organic 7th Armored Cavalry Regiment.

-

- In the early morning hours of 30 March devasting rocket, mortar, and artillery

fire fell on every fire support base in Quang Tri Province. The bombardment

continued all day, and late in the day the northernmost bases reported North

Vietnamese Army tanks and infantry moving south across the Demilitarized Zone.

Major General Frederick J. Kroesen, Jr., Deputy Commander, U.S. XXIV Corps,

described the action:

-

- The artillery offensive was followed by infantry and armor attacks in the

east across the Ben Hai River following the axis of QL (Route) 1 in the west

toward the district capital of Cam Lo and Camp Carroll. Elements of the 304th

and 308th Divisions, three separate infantry regiments of the B5 Front, two

tank regiments, and at least one sapper battalion were later identified among

the attacking forces. Initially then, the enemy concentrated a numerical advantage

of more than three to one over the defending 3d Division and attacked forces

which were disposed to counter the infiltration and raid tactics heretofore

employed by the NVA in the DMZ area.

-

- The tactical situation on 30 March was confused; the 3d Infantry Division

received vague and conflicting reports from fire bases at an astonishing rate.

Most disconcerting were accounts of the ferocity and widespread nature of

the attacks. Just before noon the 20th Tank Regiment received a frantic message

from Headquarters, Military Region 1, ordering it to return to Quang Tri City.

Since no explanation was given, Major General Nguyen Van Toan, Chief of Armor,

and his American adviser, Colonel Raymond R. Battreall, Jr., flew to Quang

Tri City to see General Vu Van Giai, the South Vietnamese 3d Division commander.

There

- [205]

- they learned that the western fire bases near the Demilitarized Zone had

been overrun in a preclude to what was apparently a major enemy offensive.

Since the main attack had not yet been identified, and since no one was sure

where the tank regiment would be of the most value, General Toan persuaded

General Giai not to commit the 20th Regiment prematurely but to hold it as

a division reserve or for use as a counterattack force. He also convinced

General Giai that he should permit the unit to stand down for maintenance

before its commitment. With that determined, the regiment, then conducting

its final coordinated assault phase of the training exercise, completed the

assault, did a right flank on the objective (out of line formation and into

a column) , and, without stopping, returned to Ai Tu Combat Base.

-

- The Rock of Dong Ha

-

- By early morning of 1 April most of the outlying fire bases along the Demilitarized

Zone and in western Quang Tri Province had been evacuated or overrun, leaving

no friendly positions north of the Mieu Giang and Cua Viet rivers. Poor weather

prevented air support and contributed to the relative ease with which the

enemy pushed back the South Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese forces advanced

south with impunity. By late afternoon on 1 April Mai Loc and Camp Carroll,

south of the Mieu Giang River, were under heavy attack.

-

- Frantically redeploying the three infantry regiments, one cavalry regiment,

and two Vietnamese Marine brigades at his disposal, General Giai established

a defensive line along the south bank of the Mieu Giang. In an effort to stabilize

the situation, he committed the 20th Tank Regiment on the morning of 1 April

with the mission of relieving the embattled 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment

and attached infantry units then fighting around Cam Lo, along National Highway

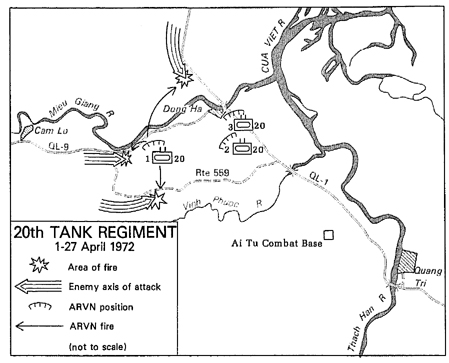

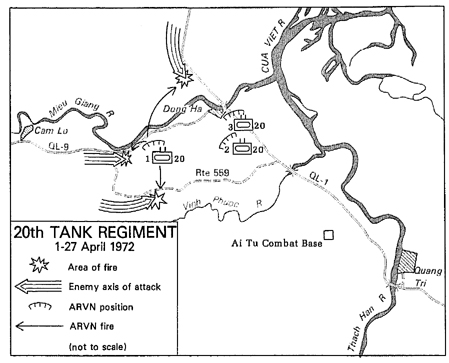

9. (Map 17) After joining a South Vietnamese Marine battalion, the

tank regiment moved north from Ai Tu along Highway 1 toward Dong Ha.

-

- Poor traffic control and refugees congesting the route forced the tank regiment

to move cross-country to the southwest of Dong Ha, and in so doing it surprised

and routed an enemy ambush along Highway QL-9. Prisoners taken during this

action were dismounted members of a North Vietnamese tank unit whose mission

was to seize and man South Vietnamese armored vehicles expected to be captured

in the offensive. With its forty-four operational tanks, the 20th Tank Regiment

moved on toward Cam Lo, which was burning. As darkness approached, the unit

set up a defensive

- [206]

- MAP 17

-

- position southeast of Cam Lo Village, withstanding enemy probes throughout

the night.

-

- At daybreak on Easter Sunday, 2 April, the 20th Tank Regiment received reports

that a large North Vietnamese tank column was moving south across the

Ben Hai River toward the bridge at Dong Ha. About 0900 the commander, Colonel

Nguyen Huu Ly, received permission to move to Dong Ha, then north across the

bridge to engage the enemy forces. When he reached the town he found enemy

infantry already occupying positions on the north bank of the Mieu Giang River

that prevented his crossing the bridge. He deployed the regiment around the

town of Dong Ha, with the 1st Squadron in a blocking position on the high

ground about three kilometers to the west, the 2d Squadron to the south, and

the 3d Squadron defending positions within the town to prevent enemy elements

from crossing the bridge.

-

- About noon men of the 1st Squadron, from their vantage point on the high

ground to the west, suddenly observed a North Vietnamese tank and infantry

column moving south along Highway 1 toward Dong Ha. Moving their tanks into

concealed positions, they waited as the enemy tanks moved closer. At a range

of 2,500 to

- [207]

- 3,000 meters, the South Vietnamese tankers opened fire, quickly destroying

nine PT76 tanks and two T54 tanks. The North Vietnamese unit, which by its

column formation showed that it was not expecting an attack, was thrown into

confusion. Unable to see their adversaries, the North Vietnamese crewmen maneuvered

their tanks wildly as the South Vietnamese tank gunners destroyed them one

by one. The accompanying infantry dispersed, and the surviving T54 tanks turned

and headed north without firing a single shot. The South Vietnamese regimental

headquarters, monitoring the North Vietnamese radio net at that time, heard

the enemy commander express surprised disbelief at losing his tanks to cannon

he could not see.

-

- The steady deterioration of the tactical situation around Dong Ha was arrested

by the arrival of the 1st Armor Brigade headquarters. Although the brigade

headquarters had been in the area solely to monitor the 20th Tank Regiment's

training exercise, it was a well trained organization, possessing the armored

vehicles and radios needed by General Giai to establish control of the scattered

forces and direct the defense he hoped to establish at Dong Ha. General Toan

had urged its employment, and on the afternoon of 2 April the brigade, under

3d Division control, assumed command of all armored, infantry, and Marine

forces in the Dong Ha area. Its units included the 20th Tank Regiment, two

squadrons of the 17th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the 2d and 57th Regiments

of the 3d Infantry Division, the 3d Battalion of the 258th Marine Corps Brigade,

and the survivors of the 56th Regiment from Camp Carroll.3

-

- The bridge spanning the Mieu Giang River at Dong Ha afforded the enemy the

opportunity to cross the river unimpeded and then drive straight south to

Quang Tri City. Before the armor brigade headquarters arrived, the 3d Division

engineers had made two unsuccessful attempts to destroy the bridge with explosive

charges. When Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat, the 1st Armor Brigade commander,

arrived he decided to leave the bridge intact for the time being, since the

enemy had been stopped and the armor brigade forces were holding. Colonel

Luat was preparing to make a counterattack to the north across the bridge

when the bridge charges detonated and dropped the near span, putting an end

to any counterattack plans.

- [208]

- Other enemy forces continued to move south toward Dong Ha on the afternoon

of 2 April, engaged first by limited tactical air strikes and then by artillery,

mortar, and tank fire. A large search and rescue effort had been launched

for the crew of a U.S. aircraft downed near Cam Lo. The U.S. Air Force temporary

nofire zone was twenty-seven kilometers in diameter, encompassing nearly the

entire combat area and South Vietnamese Army defenders were unable for several

hours to call for artillery support or tactical air strikes against the onrushing

North Vietnamese Army. The enemy therefore had an opportunity to advance artillery,

tanks, and infantry until 2200, when the restriction was lifted.

-

- During the next several days, enemy activity was relatively light, with

sporadic attacks by fire and numerous small ground actions. The North Vietnamese

artillery fire was extremely accurate, and although South Vietnamese units

moved frequently to avoid the shelling the enemy seemed to be able to locate

new positions very quickly. On 3 April a North Vietnamese artillery observer

in a South Vietnamese officer's uniform and driving a South Vietnamese vehicle

with radios was captured south of Dong Ha. The observer had papers supporting

several identities, and spent his time driving throughout the area spotting

and adjusting artillery fire for North Vietnamese guns near the Demilitarized

Zone. Although South Vietnamese units conducted attacks to eliminate pockets

of resistance south of the Mieu Giang River, the pressure from the north remained

intense.

-

- The next tank combat occurred on the 9th when all three squadrons of the

20th Tank Regiment fought enemy armor. The 1st Squadron, shifted several kilometers

west of Dong Ha six days earlier, occupied high ground overlooking an important

road junction along National Highway 9. Again the tank gunnery training paid

dividends as the tankers engaged an infantry unit supported by ten tanks at

ranges up to 2,800 meters. A few answering shots fell short, and the enemy

tanks scattered, several bogging down in the rice paddies near the road. Eventually

eight were destroyed. In all, the regiment destroyed sixteen T54 tanks and

captured one T59 that day, in turn suffering nothing more than superficial

damage to several M48's.

-

- For the next two weeks the South Vietnamese carried out clearing operations

interrupted by frequent engagements with North Vietnamese armor and infantry

which normally withdrew in the late afternoon. Nights were punctuated by artillery,

mortar, and rocket attacks on South Vietnamese positions throughout the area.

The defensive lines established on 2 April continued to hold,

- [209]

-

NORTH VIETNAMESE T59 TANK captured by South Vietnamese

20th Tank Regiment south of Dong Ha.

-

- and on 11 April the 1st Armor Brigade was augmented by the arrival of the

18th Armored Cavalry Regiment from Military Region 3. By 14 April the 3d Division

controlled five regimental size South Vietnamese task forces, including units

of the 4th, 11th, 17th, and 18th Cavalry Regiments and the 20th Tank Regiment.

-

- On 23 April, several kilometers west of Dong Ha, the 2d Squadron of the

20th Tank Regiment was attacked by an infantry-tank force using a new weapon.

For the first time the enemy employed the Soviet AT3 Sagger wire-guided missile,

destroying an M48A3 tank and an armored cavalry assault vehicle. A second

assault vehicle was damaged. At first the South Vietnamese Army tankers seemed

fascinated by the missile's slow and erratic flight. Through trial and error,

however, the troops soon learned to engage the launch site of the AT3 with

tank main gun fire and to move their vehicles in evasive maneuvers.

-

- Heralded by massive artillery attacks with 122-mm. rockets and 130-mm. guns,

on 27 April a new enemy offensive began against South Vietnamese Army positions

all along the Mieu Giang-Cua Viet River defense line. The barrage was quickly

followed by

- [210]

- violent attacks by enemy infantry and armor, met by equally determined resistance

on the part of the South Vietnamese defenders. The 3d Squadron, 20th Tank

Regiment, supporting the 5th Ranger Group, received the brunt of the attack

and was soon heavily engaged. By midmorning all officers of the 3d Squadron

had been killed or wounded, and three M48A3 tanks had been destroyed by Sagger

missiles.

-

- All along the defensive line, units were being overrun or pushed back. Forced

to yield ground, Ranger and tank elements gradually withdrew to the southeast,

Although losses were heavy on both sides, the numerically superior North Vietnamese

continued their drive, and by nightfall had pushed almost four kilometers

south of Dong Ha. In the early morning of 28 April, the 20th Tank Regiment

had eighteen operational M48A3 tanks. During the South Vietnamese withdrawal

the accurate gunnery of the 3d Squadron cost the North Vietnamese five T54

tanks.

-

- At that point the South Vietnamese found large enemy forces to their rear

and for the armored units the withdrawal became an attack to the south. The

2d Squadron of the tank regiment, attacking south to secure the bridge over

the Vinh Phuoc River at midmorning on the 28th, was badly battered in an enemy

ambush. The commander lost control of his unit and the surviving vehicles,

after crossing the bridge, continued to the south in disarray.

-

- It was then obvious to Colonel Luat that 1st Armored Brigade units were

threatened with encirclement, so the entire force began moving south. All

along the way fighting was heavy for the next two days. The terrain as well

as the enemy took its toll of vehicles. At the Vinh Phuoc River seven vehicles

were stranded on the north shore when the bridge, struck by enemy artillery

fire, collapsed.4

Farther south at the Thach Han River near Quang Tri City, the bridges

were already destroyed. Two tanks were lost there in fording the river on

the 30th.

-

- By then the tank and cavalry units were beginning their fifth day of almost

constant fighting. South of Quang Tri resupply of fuel and ammunition was

nonexistent as the armored force continued its attack. Forced from the highway

by a determined enemy, the tanks and assault vehicles moved cross-country,

falling victim to the many rice paddies, canal crossings, and streams as well

as the antitank rockets and artillery. On the first day of May the vehicles

began to run out of gas.

- [211]

- Finally, on 2 May, having fought their way through the last enemy units,

the battered survivors of the armor command, intermingled with the remnants

of other army units, reached Camp Evans at midafternoon. Only armored cavalry

assault vehicles were left; the cavalry regiments and the tank regiment had

lost all their tanks. The once proud 20th Tank Regiment was reduced to a demoralized,

dismounted, and defeated unit. Employed primarily in a static, defensive role

in frontline areas, the unit had steadily lost men and equipment without receiving

replacements. Although vastly outnumbered, cavalry, infantry, tank, and Marine

units of the 1st Armor Brigade, as well as tenacious Regional Forces and Popular

Forces to the east, had succeeded in slowing the momentum of the massive North

Vietnamese invasion. With assistance from U.S. and Vietnamese tactical air

forces, they provided the resistance that delayed the enemy until enough reinforcements

could be brought up to halt the offensive.

-

- The Enemy Attack in Military Region 2

-

- In Military Region 2 essentially the same preliminary enemy activity took

place that had been seen in Region 1. As early as mid-December 1971, air cavalry

reconnaissance confirmed reports of large-scale troop movements in the border

areas of Cambodia and Laos. The 7th Squadron, 17th U.S. Cavalry (Air), engaged

two tanks and sighted four others west of Kontum on 25 January 1972, but the

advisory staff of Military Region 2 failed to recognize the importance of

the reports. Enemy units were reportedly staging for a campaign against population

centers like Kontum and Pleiku, to be supported with attacks by local Viet

Cong units in the coastal lowlands designed to draw off South Vietnamese forces.

-

- To counter what appeared to be a growing threat to Kontum, the regional

commander, Lieutenant General Ngo Dzu, moved the bulk of the 22d Infantry

Division to Tan Canh and Dak To II, including the division's organic 14th

Armored Cavalry Regiment as well as reinforcing elements from the 1st Squadron

(tank), 19th Armored Cavalry Regiment. (See Map 16, inset.) Most of

the M41 tanks of both regiments were in position at Ben Het by order of the

22d Division commander, against the advice of the 2d Armor Brigade commander,

who argued that cavalry should be used in a mobile role. In mid-March encounters

with large enemy units along Rocket Ridge and near Ben Het, intelligence and

prisoner reports indicated that a full-scale offensive supported by tanks

was being planned for the period April to September.

-

- By 23 April Tan Canh and Dak To II were effectively sur-

- [212]

-

DISABLED M48 OF THE SOUTH VIETNAMESE 20TH TANK REGIMENT.

Road wheels received hit from rocket near My Chanh River.

-

- rounded by North Vietnamese forces, and in the afternoon of that day an

M41 tank of the 1st Squadron, 14th Cavalry, returning through the main gate

of the compound at Tan Canh, was hit and destroyed by a Sagger missile. Within

moments additional missiles hit the reinforced bunker that served as the tactical

operations center for the 22d Infantry Division, killing or wounding several

members of the staff. Shortly thereafter the remaining M41 tanks within the

Tan Canh compound were also destroyed by missiles.

-

- At 2100 a column of eighteen North Vietnamese tanks was reported moving

south toward Dak To. Shortly after dawn on 24 April, enemy tanks and infantry

attacked two sides of the Tan Canh perimeter, causing confusion and panic

among South Vietnamese Army support troops. These troops fled, followed not

long after by the remaining South Vietnamese Army combat troops, who had been

surprised and demoralized by the sudden onslaught of the T54 tanks.

-

- At Dak To II, five kilometers to the west, North Vietnamese infantry and

T54 tanks penetrated the perimeter in several places. By midafternoon both

bases were in enemy hands, and the scat-

- [213]

- UH-1B HELICOPTER WITH TOW MISSILES lifts off strip at Pleiku.

-

- tered, disorganized remnants of the 22d Infantry Division were evading capture

in the jungle.

-

- The North Vietnamese spent the next several days consolidating their positions

and tallying up the massive arsenal South Vietnamese units had abandoned intact:

Twenty-three 105-mm. howitzers, seven 155-mm. howitzers, a number of M41 tanks,

and about 15,000 rounds of artillery ammunition.

-

- On 25 April South Vietnamese forces abandoned their precariously positioned

fire bases along Rocket Ridge, thereby allowing the enemy to proceed unhindered

down Highway QL-14 toward Kontum City. The city, meanwhile, was being hastily

fortified by elements of the South Vietnamese 23d Infantry Division, which

had been given control over all forces in Kontum Province. Between 25 April

and 9 May, enemy attacks were made against Ben Het and Polei Kleng Ranger

camps located astride North Vietnamese supply routes. While Polei Kleng fell

on 9 May, Ben Het stood -firm against repeated tank and infantry attacks throughout

the campaign. By this time attacking enemy units had been identified as elements

of the 2d and 320th North Vietnamese Divisions, supported by the 203d Tank

Regiment.

-

- The 23d Infantry Division commander, Colonel Ly Tong Ba, who had commanded

the original M113 mechanized rifle company in 1963 as a captain, now worked

feverishly to prepare his troops both physically and psychologically to withstand

an enemy attack spearheaded by armor. He instituted an intensive program to

train

- [214]

- division soldiers in the use of the M72, an American light antitank weapon,

and tried to instill confidence in the individual soldier that he could destroy

an enemy tank with the weapon. Artillery concentrations were planned and coordinated

with B-52 bomber strikes, and practice counterattacks were made in areas of

possible penetration. All in all, the time the South Vietnamese gained by

the enemy failure to follow up the overwhelming victory at Tan Canh was put

to good use.

-

- At this time a new weapon, destined to change the complexion of armored

warfare, appeared on the battlefield in Military Region 2. On 24 April the

1st Combat Aerial TOW Team arrived in Saigon. Organized to participate in

an experiment at Fort Ord, California, the team was alerted on 15 April for

deployment to Vietnam to conduct an extension of the original test under combat

conditions. The team consisted of three crews, two UH-1B helicopters mounting

the XM26, a tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided missible (TOW),

and technical representatives from Bell Helicopter, Hughes Aircraft, and the

U.S. Army Missile Command. When they arrived in Vietnam, the team moved to

Pleiku for gunnery training, and after 2 May made daily flights in

search of enemy armor. On 9 May, during a North Vietnamese attack on the Ben

Het Ranger camp, the TOW team destroyed its first three PT76 tanks and broke

up the enemy assault.

-

- On 13 May intercepted enemy radio traffic confirmed earlier reports by air

cavalry scouts that there was a large buildup of North Vietnamese armor and

infantry near Vo Dinh, a signal that an all-out attack on Kontum was imminent.

At dawn on 14 May the attack began. Remembering the ease with which they had

taken Tan Canh, the North Vietnamese dispensed with an artillery preparation

and attacked south along Highway QL-14 with two regimental-size task forces

supported by tanks. A third regiment advanced from the northeast, and a fourth

probed the city's southern defenses.

-

- The 23d Infantry Division's intensive antitank training paid off on the

morning of 14 May. Tank killer teams equipped with the LAW quickly destroyed

most of the attacking tanks, leaving U.S. tactical aircraft and the TOW team

the job of picking off the remainder, which were attempting to flee back up

Highway 14. The TOW team destroyed two T54 tanks. By 0900 the attack had been

repulsed, although sporadic ground probes and artillery and mortar fire continued

throughout the day and night.

-

- For the next few days, Kontum City was pounded by indirect fire and occasionally

assaulted by small units. On 21 May the 23d

- [215]

-

ACAV OF SOUTH VIETNAMESE 17TH ARMORED CAVALRY takes

up position near My Chanh for counterattack, July 1972.

-

- Infantry Division directed a task force composed of two Ranger groups and

the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment to clear Highway QL-14 north from Pleiku to

Kontum. Clearing was successful as far as the Chu Pao Pass, about 15 kilometers

south of Kontum, where it was stalled by determined enemy resistance and the

loss of several vehicles.

-

- At 0100 on 26 May the North Vietnamese Army started a second determined

attempt to overrun Kontum City. Tank and infantry teams attacked from the

north under cover of heavy artillery bombardment and soon made several penetrations

between defending South Vietnamese elements. TOW aircraft were brought from

Pleiku at first light and arrived over Kontum to find enemy tanks moving almost

at will through the northern sections of the city. Tactical air and gunships

could not be used without risk to friendly forces but the TOW proved ideal

for the delicate task of picking off enemy tanks.

-

- The first TOW crew, Chief Warrant Officers Edmond C. Smith and Danny B.

Rowe, flew three sorties, destroying five T54 tanks and one PT76 tank, and

damaging a PT76 tank. On the second sortie the TOW missile's pinpoint accuracy

was demonstrated when it destroyed an enemy machine gun emplacement atop a

concrete water tower. The second crew, consisting of Chief Warrant Officers

Douglas R. Hixson and Lester F. Whiteis, in two sorties destroyed

- [216]

- three more PT76 tanks, a truck, and another enemy machine gun that had replaced

the gun on the same water tower.

-

- After bombarding Kontum with artillery during the night, the North Vietnamese

attacked again on the morning of 27 May with tanks and infantry. The defenders

were aided by TOW-equipped helicopters, air cavalry teams, U.S. Air Force

and South Vietnamese Air Force tactical aircraft, and planned B-52 strikes

that pounded the attacking enemy. On the ground, South Vietnamese infantry

supported by tanks from the 8th Armored Cavalry Regiment fought to dislodge

the enemy from the northern part of the city, and fierce house-to-house fighting

went on in the southern part. The battle continued through 30 May with neither

side making visible progress. By midday on 31 May enemy troops, needing resupply

and battered by several days of attack from both air and ground forces, withdrew,

leaving behind nearly 4,000 dead.

-

- The stranglehold on the supply line to Kontum was finally broken on 19 June

when the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment succeeded in reaching the city. After

several weeks of bloody fighting along Highway QL-14 at the Chu Pao Pass,

the 3d Cavalry turned the entrenched North Vietnamese position by maneuvering

west. There could be no doubt that the enemy had suffered a resounding defeat

in Military Region 2.

-

- The Aftermath

-

- In Military Region 3 the North Vietnamese attacks were just as fierce as

those in the other two regions, but they were less successful because of massive

fire support and a very determined defense by South Vietnamese infantrymen.

Armored units participated in the counterattacks and relief columns but were

not employed effectively as hard-hitting offensive forces. Only Military Region

4 escaped a formal attack. June, July, and August 1972 were months of reassessment

and realignment of forces and ideas in South Vietnam. Scattered units were

re-formed, new units were organized, and plans were made for a counteroffensive

to restore national boundaries. The South Vietnamese made these preparations

knowing only minimal U.S. support would be available. In keeping with previously

announced redeployment schedules, American troops continued to withdraw, with

the exception of Army and Air Force aviation units. The separate air cavalry

troops remaining in the country participated in varying degrees during the

counteroffensive period. Typical missions included bomb damage assessment,

visual reconnaissance in support of South Vietnamese ground units, and routine

security missions.

- [217]

- Initial resistance to the South Vietnamese counteroffensive was moderate

in Military Region 1 but increased sharply as the enemy fell back toward Quang

Tri City. Attacking forces were the Marine and Airborne Divisions, supported

by armored units from the 1st Armor Brigade (the reconstituted 20th Tank Regiment

and the 11th, 17th, and 18th Armored Cavalry), and some Ranger units. During

the attack and capture of Quang Tri City on 16 September and afterward, small

unit combined arms operations were used successfully by several commanders.

Often these operations were not directed by higher headquarters but were planned

and carried out by commanders at battalion level. For this reason, their successes

were more noteworthy.

-

- During the final months of 1972 both sides prepared for peace. These preparations

included a massive infusion of arms and equipment by both sides. In an eleventh-hour

American effort in late November, 59 tanks, 100 armored personnel carriers,

and over 500 aircraft were shipped to South Vietnam.5

North Vietnam attempted a similar buildup for North Vietnamese forces

in the south, but had to contend with massive B-52 bomber raids along their

supply routes.

-

- A peace accord was scheduled to become effective in Vietnam at 0800 on 28

January 1973, after nearly five years of on-again, off-again negotiations

between Hanoi and the United States. After several false starts and many months

of false hopes, peace seemed to be at hand. In fact, the bloodletting was

far from over.

-

- With the 28 January cease fire, the last U.S. advisers left the country,

and for the first time South Vietnamese divisions and corps were truly on

their own. Not only were there no advisers to summon and coordinate the once

vast U.S. tactical and strategic air power, naval gunfire, and on-call resupply

but these resources themselves no longer existed. But although some South

Vietnamese commanders were forced to readjust their battlefield techniques,

most armored commanders had not become overly dependent on air support. The

organic firepower available to armored unit commanders generally had made

them more self-sufficient and self-confident than commanders of other ground

units. Consequently, the departure of advisers from tank and cavalry units,

which in most cases had already occurred by mid-1971, did not have much impact.

-

- With the cease fire came an overdue change in the role of

- [218]

- armored forces in Vietnam. Armored units had been employed in a purely tactical

role as frontline troops for maneuver and fire support. In practically every

operation of size or note, cavalry was there, slugging it out alongside infantry

or spearheading an offensive against an enemy sanctuary. But the conventional

warfare and large-scale operations initiated by the North Vietnamese during

their spring offensive of April 1972 had dictated a substantial change in

this employment. Continuous frontline exposure of armored units in static

defensive positions soon resulted in unacceptably high losses in men and vehicles.

Fortunately, there appeared to be growing awareness among high level commanders

and staff officers of the need to use armored and cavalry forces as mobile

reserves.

-

- The experiences of April 1972 made it immediately apparent that using armored

units in a static role, where inherent advantages of firepower, mobility,

and shock effect could not be exploited, invited piecemeal destruction. The

tactical situation that existed immediately before and for some time after

the cease fire was ideal for the employment of armored forces as mobile reserves.

- [219]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-