- Chapter III:

Riverine Preparations in the United

States and in Vietnam

During the final preparation of the Mobile Afloat

Force plan in South Vietnam, the 9th Infantry Division was activated at Fort

Riley, Kansas, on 1 February 1966 under the command of Major General George

S. Eckhardt. This was the one infantry division to be organized in the

United States during the fighting in Vietnam -the so-called Z Division that

had been scheduled for operations in the Mekong Delta. It was probably no,

coincidence that the division had been designated the 9th U.S. Infantry;

General Westmoreland had seen extensive service with the 9th in World War

II, having commanded the 60th Infantry and having served as chief of staff

of the division during operations in both France and Germany.

Because of a shortage of men and equipment the activation order provided

for incremental formation of the division. Division base elements such as

the headquarters and headquarters company, division support command, and

brigade headquarters and headquarters companies were activated first.

Activation of the battalions of each brigade was phased, commencing in April

for the 1st Brigade, May for the ?d Brigade, and June for the 3d Brigade.

The artillery and separate units were scheduled for activation during April

and May. Some of the division's officers who had been previously assigned to

the Department of the Army staff had learned that the 9th Infantry Division

was scheduled to operate in the southern portion of the III Corps Tactical

Zone and the northern portion of the IV Corps Tactical Zone and that it was

to provide a floating brigade. This information was not discussed officially

but was known to the brigade commanders and the division artillery

commander.

The division was organized as a standard infantry division composed of

nine infantry battalions of which one was initially mechanized. It had a

cavalry squadron and the normal artillery and supporting units. The division

training program was limited to

[42]

eight weeks for basic combat training, eight weeks for advanced

individual training, and eight weeks for both basic and advanced unit

training-a total of twenty-four weeks. This compression of training time

eliminated four weeks from each of the unit training periods and the four

weeks usually allowed for field training exercises and division maneuvers-a

total of twelve weeks from the normal Army training time for a division.

Although it was not generally known in the division, the division training

period as established in Army training programs had been reduced in order to

conclude at the time of the beginning of the Vietnam dry season in December

1966 when the MACV plan called for the introduction of U.S. ground forces

into the Mekong Delta.

The normal Army training programs were followed for the basic combat and

advanced individual training. General Eckhardt, perceiving that the existing

training programs had limitations for combat in Vietnam, by means of a

personal letter gave his brigade commanders the latitude to make innovations

and to modify training in order to prepare their men for the physical

conditions and the tactics of the enemy in Vietnam. The training given by

the brigade commanders was based on lessons learned and standing operating

procedures of United States units then fighting in Vietnam. Although aware

of possible employment of his unit in the Mekong Delta, each of the brigade

commanders required the training he deemed advisable to prepare his unit for

operations in any part of Vietnam. Although the brigade afloat had not been

designated, Colonel William B. Fulton, Commanding Officer, 2d Brigade, felt

that the mission could ultimately be assigned to his brigade. Because the

training period was short, however, he elected to adhere to normal basic

training in counterinsurgency for his units.

Colonel Fulton established a training course for the brigade and

battalion commanders and their staffs that was designed to develop

proficiency in command and staff actions for land operations in Vietnam. The

class was held every ten days in a map exercise room with a sand table and

map boards depicting selected areas of Vietnam. The sessions lasted

approximately five hours. Three days before the class a brigade operations

order was issued to the battalion commanders, requesting each battalion to

prepare plans and orders in accordance with the brigade tactical concept. At

the start of the session the brigade staff outlined the situation. Each

battalion commander was then required to furnish a copy of his orders and to

explain why he deployed his units as' he did: There was a general critique,

after which a new situation was

[43]

assigned for study. Each commander and his staff, which included

representatives of artillery, engineer, aviation, and other supporting

elements, then prepared the next set of orders. These in turn were presented

to the group for analysis and critique.

The commanders and staff studied various forms of land movement by

wheeled and tracked vehicles on roads and cross-country. Next, air movement

was considered, including troop lift and logistics computations, various

formations, and the selection of landing and pickup zones. This in turn was

followed by a study of water movement by small craft.

In conjunction with command and staff training, the brigade was

developing a standing operating procedure, which was reviewed at sessions of

the command and staff course. The course began in May when the brigade was

activated and was separate from the Army training programs being undertaken

by the units. Officer and noncommissioned officer classes in the subject

matter covered in the Army training programs were conducted at the battalion

level.

Following the map exercises on movement, a series of exercises was

conducted involving the organization and security of the base area and

patrolling outside of the base in the brigade tactical area of

responsibility. Subsequently, exercises were conducted combining both air

and ground movement in search and destroy operations.

The brigade patterned its standing operating procedure and its methods of

tactical operations primarily after those of the 1st Infantry Division. At

the time that the command and staff training course was in full swing,

several unit commanders from the 1st Infantry Division were returning from

Vietnam to Fort Riley and Junction City, Kansas, where they had left their

families when they departed with the 1st Division in 1965. Extensive

interviews were conducted by the brigade commander and staff, who

incorporated the information obtained into the standing operating procedures

and the command and staff course.

The command and staff course did not specifically deal with riverine

operations. Some of the map exercises were plotted in the northern delta

immediately adjacent to the Saigon area and Di An where the 1st Division was

operating, and one problem explored water movement. Too little was known

about riverine operations to incorporate them fully into training.

Furthermore, Colonel Fulton felt that the basic operational essentials

should be mastered first; riverine operations could be studied after unit

training was completed.

[44]

On receipt of the MACV Mobile Afloat Force concept in

mid-March 1966, the Commander in Chief, Pacific, Admiral Sharp, requested

that it be reviewed by the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, Admiral Roy L.

Johnson. The latter generally concurred in the plan but pointed out that

while the Mobile Afloat Force concept provided for maintaining a brigade in

the delta for up to six months, it might be necessary to rotate the APB's

for maintenance and upkeep every two to three months.

Admiral Sharp had questioned the command arrangements. Under the Mobile

Afloat Force plan it had been recommended that the Navy commander be charged

with the security of the mobile base, while the Army brigade commander would

provide support. Admiral Johnson, on the other hand, believed that the Army

commander should be responsible for base security with the Navy commander

providing supporting fire and protection against waterborne threat. He also

questioned whether the Mobile Afloat Force could search junks effectively

and protect naval craft against water mines and ambushes. He expressed

concern that hydrographic charts of the delta waterways were incomplete, and

that river assault craft were not properly designed and were, furthermore,

too noisy.

Except for operational control, the Navy units were under the control of

the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet. The Commander, Amphibious Force,

Pacific, and Commander, Service Force, Pacific, had specific

responsibilities and part of the subsequent success of the force stemmed

from the professional manner in which the Navy fulfilled its obligations. In

the case of logistics, support was given not only by units in Vietnam such

as the harbor clearance units of Service Force, Pacific, but also by other

units of the logistic support system, afloat and ashore, as set forth in the

support plan of the Service Force. Each of the commanders concerned felt

personal responsibility for the performance of those of his units that would

be operating under Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

As staffing of the Mobile Afloat Force proceeded, General Westmoreland

continued to call attention to the need for beginning immediately U.S.

operations in the Mekong Delta. In a message to Admiral Sharp on 11 May,

with respect to intensification of the efforts of Vietnam armed forces and

early initiation of U.S. operations in the Mekong Delta, he stated that

"enemy access to Delta resources must be terminated without

delay."

[45]

The planned deployment into the delta had appeared in MACV Planning

Directive 3-66 published 21 April 1966. The directive had emphasized

widening the range of operations in the northern coastal areas of South

Vietnam and close-in clearing and securing operations around Saigon. It did

not provide for any major American effort in the delta during the rainy

season of May-November 1966, but the possibility of short operations by

units such as the Special Landing Force was cited. These operations were to

have as their target the mangrove swamps along the coastal areas in the

southern III Corps and northern IV Corps Tactical Zones. Plans for the

operations were based on the success of operation JACKSTAY in the Rung Sat

Special Zone in 1966.

General Westmoreland expected to send forces in late 1966 and early 1967

from the III Corps Tactical Zone to the Plain of Reeds and other northern

delta areas. The planning provided for the Commanding General, 11 Field

Force, Vietnam, Lieutenant General Jonathan O. Seaman, to assume command of

U.S. tactical operations in the IV Corps Tactical Zone, co-ordinating

operations with the Commanding General, IV Corps, through the American

senior adviser who was to be a brigadier general. (Colonel William D.

Desobry, Senior Advisor, IV Corps Tactical Zone, was promoted to brigadier

general in August of 1966.)

On 29 May 1966 General Westmoreland was briefed on the deployment of the

9th Infantry Division to the IV Corps Tactical Zone. He approved the plan

and ordered his staff to discuss with General Seaman an alternate location

for the 9th Division base. General Westmoreland directed that the Mobile

Afloat Force plan to locate a division headquarters and one brigade at Ba

Ria be reconsidered. He called attention to his previous decision that the

9th Division would be placed under General Seaman to facilitate tactical

operations along the III and IV Corps border and that the Commanding

General, 9th Division, would not become the senior adviser to the IV Corps

Tactical Zone. General Westmoreland pointed out further that the

introduction of a division force into IV Corps would require discussion with

General Cao Van Vien, chairman of the joint General Staff of the Republic of

Vietnam.

On 9 June General Westmoreland suggested that the delta might well be a

source of stabilization of the Vietnamese economy. The delta could produce

enough rice for the entire country if it were kept under government control;

other areas of the country would then be free to industrialize. The delta

was also the source

[46]

of nearly 50 percent of the country's manpower. It therefore followed

that development of the region had to be accelerated; sending in a U.S.

division would aid in this acceleration.

On 10 June General Westmoreland discussed with General Vien and

Lieutenant General Dang Van Quang, Commanding General, IV Corps Tactical

Zone, the possible introduction of U.S. forces into the IV Corps Tactical

Zone. On 13 June the matter came up for discussion in the Mission Council

meeting. General Quang, who had made a statement to the press some weeks

earlier against the stationing of U.S. troops in IV Corps, but in the

meantime had apparently had a change of heart, now expressed in the meeting

a desire that a U.S. brigade be stationed in IV Corps. General Westmoreland

told the council that a final decision on the matter of basing American

troops in IV Corps would be made in October. Dredges had already been

ordered, and the proposed site would be ready by December. He further stated

that the troops would be located about eight kilometers from My Tho, which

would be off limits to U.S. troops, and that travel through My Tho would be

sharply restricted. Since the base would be completely self-sufficient, it

would be no drain on local resources. When Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge,

Jr., and the political counselor expressed reservations, General

Westmoreland agreed with them that it would be preferable to use Vietnamese

troops, but pointed out that up to this time Vietnamese troops had not been

completely successful in the delta, and important Viet Cong units were still

operating there.

The land base had been selected by General Westmoreland himself from four

sites submitted by the engineers as suitable for building by dredging. The

sites were designated W, X, Y, and Z, and the one near My Tho chosen by

General Westmoreland was W. The general's staff immediately referred

phonetically to Site W as Base Whisky, the word used in the military

phonetic alphabet for the letter W. General Westmoreland felt that the site

should be given a significant name in keeping with its role as the first

American base camp in the Mekong Delta. He asked the official MACV

translator to give him several possible Vietnamese names for the base, such

as the translation of "friendship" or "co-operation."

The translator's list included the Vietnamese term Dong Tam, literally

meaning "united hearts and minds." General Westmoreland selected

this name for three reasons: first, it signified the bond between the

American and Vietnamese peoples with respect to the objectives to be

achieved in the delta. Second, it connoted an appro-

[47]

LANDING CRAFT REPAIR SHIP WITH ARMORED TROOP CARRIERS

priate objective compatible with the introduction of U.S. forces into the

populous delta where their prospective presence had evoked some official

concern. Third, Dong Tam was a name which Americans would find easy to

pronounce and remember. Having chosen the name of Dong Tam, General

Westmoreland asked General Vien, the chairman of the joint General Staff,

his English translation of the name. General Vien confirmed that

"united hearts and minds" was the literal translation. Thus the

name Base Whisky was changed to Dong Tam, which became a well-known landmark

during the subsequent co-operative efforts of American and Vietnamese troops

in the delta.

Later in the month, at the Honolulu Requirements Planning Conference, the

Mobile Afloat Force was included in requirements for the calendar years 1967

and 1968.

The Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force will provide a means to introduce,

employ and sustain substantial U.S. combat power in that vital area.

Introduction of the MDMAF [Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force] at the earliest

practicable date, whether it be an increment of that force or all of it,

will provide a capability for more rapid achievement of U.S. objectives in

that area.

[48]

These requirements as set forth in the conference provided for the

arrival of the first component of that force by April 1967 and the second,

final component by March 1968.

On 5 July Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, approved activation

and deployment of a Mobile Afloat Force consisting of two river assault

groups. At the time of the approval, he reduced the number of self-propelled

barracks ships from five to two and eliminated one landing craft repair ship

from the force. He was not willing to provide for the total package

requested for the Mobile Afloat Force because he felt that the force could

be fully tested with the equipment he had approved. Included in the cut was

the salvage force, which required two heavy lift craft of 2,000 tons, two

YTB's altered for salvage, two LCU's, and three 100-ton floating dry docks.

Only one YTB was authorized. Secretary McNamara's decision was to have an

appreciable impact on the preparation for and the operations of the Mobile

Riverine Force as it was constituted in June of the following year.

Subsequently General Westmoreland, through Admiral Sharp, requested

reconsideration of the decision to field only two self-propelled barracks

ships and two river assault groups; again four river assault groups and at

least four barracks ships were requested.

In view of the request, the joint Chiefs of Staff asked for an evaluation

of the planned employment and of the additional effectiveness which these

ships and craft would contribute to the force. Such an evaluation already

had been completed by the MACV staff in May. The evaluation pointed out the

lack of firm ground for stationing major troop elements and noted that

"the time consuming process of dredging" required to base

additional units on land justified the additional two barracks ships.

Admiral Johnson called attention to the fact that the Mobile Afloat Force

concept also provided for a mobile brigade independent of a land base. One

brigade of the. 9th Division was to be stationed at Dong Tam in early 1967.

When barracks ships became available, a reinforced battalion from a brigade

in III Corps Tactical Zone would be put afloat.

The two river assault groups approved by Secretary McNamara for fiscal

year 1967 would be stationed at Dong Tam. Omission of the repair boat to

provide mobile maintenance would preclude the permanent basing of assault

groups with the two barracks ships in the first increment of the Mobile

Afloat Force. Either assault group would be available on call from a land

base to provide lift for a

[49]

battalion afloat. Some of the boats of an assault group would remain to

protect the barracks ships.

Units of the 9th Division not stationed at Dong Tam or aboard APB's would

be based in III Corps Tactical Zone north and east of the Rung Sat Special

Zone, permitting extensive operations into the special zone and IV Corps by

assault group craft. With the arrival of a third assault group, which would

include an ARL, one group could be permanently assigned to the forces

afloat. This would leave two river assault groups assigned to Dong Tam for

lifting battalions of that brigade or the other brigade from the Vung Tau

area for operations in the upper delta. When the second increment arrived,

at least two river assault groups would be needed for the floating base and

one each to support the other two brigades of the 9th Division.

General Westmoreland strongly recommended to Admiral Sharp that the two

additional APB's and assault groups be included in the calendar year 1967

force requirements and that they be activated and deployed at the earliest

practicable date. Admiral Sharp supported General Westmoreland's position

and forwarded it to the joint Chiefs of Staff on 16 July, with a further

justification of the two river assault groups on the grounds that

"projection of U.S. combat operations into the Delta is an objective of

major importance." Admiral Sharp stated that with three thousand

kilometers of navigable waterways, an absence of adequate roads, and a lack

of helicopters, the 9th Division, which "will be the principal riverine

ground combat force," would require river assault group support. Four

groups (two organic to the Mobile Afloat Force and two additional) could

lift about half of the riverine ground force at any one time. In addition,

river assault group craft would be used in reconnaissance and patrolling

missions and resupply operations, would reinforce GAME WARDEN and MARKET

TIME operations when necessary, and would support operations to open and

secure important water routes.

In August while the question of whether to increase the number of Navy

boats was being decided at higher headquarters, in Vietnam Mobile Afloat

Force preparations were nearing completion. On 1 August, MACV published

Planning Directive 4-66 Operations in the Delta. The directive called for

employment of riverine forces "regardless of whether based on land

(Dong Tam or elsewhere) or on MDMAF [Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force]."

Composition of a river assault group was established as 26 armored troop

carriers, 16 assault support patrol boats, 5 monitors, 2 com-

[50]

mand communications boats, and 2 LCM-6 refuelers. This composition was to

vary little throughout the entire period of river assault group operations.

The MACV plan would operate in three phases. During the first, the

Construction Phase, 1 July 1966-31 January 1967, all actions required to

prepare the ground and facilities for occupation of the base would be

completed. In the second, the Preparation and Occupation Phase, also to run

from 1 July 1966 through 31 January 1967, all actions required to prepare

the Army and Navy units to occupy bases, and the actual occupation would be

completed. Preparation of the forces would proceed concurrently with base

construction. The Improvement and Operations Phase would begin when the Army

and Navy units had occupied the bases and were ready to begin combat

operations. All actions necessary to conduct and sustain combat operations

from the Dong Tam base would be undertaken during this phase and base

facilities would be improved and expanded as necessary.

In July 1966 the 9th Division at Fort Riley bad been furnished copies of

the plan and requirements of the Mobile Afloat Force. These were studied by

the division staff and, after approximately two weeks, the chief of staff,

Colonel Crosby P. Miller, assembled the brigade commanders. In very broad

terms, Colonel Miller outlined the intended area of operations for the

division and referred to the provision for a brigade afloat. This briefing

aroused the curiosity of Colonel Fulton, commander of the 2d Brigade. He

requested copies of the complete plan for study by himself and his staff,

and the division commander approved. An intensive analysis was then made by

the appropriate staff officers and the study was returned to division

headquarters.

Exhibiting the foresight that had characterized its planning effort, MACV

sent one of the principal planners for the Mobile Afloat Force to the United

States on normal rotation and placed him on temporary duty with the 9th

Division for a week. This officer, Lieutenant Colonel John E. Murray, Field

Artillery, was extremely enthusiastic about the project and was familiar

with all aspects of the plan and with the area of intended operations in the

delta. Colonel Fulton arranged for Colonel Murray to spend some time with

his brigade staff and battalion commanders to discuss all facets of the

project. Through questions and, answers, a clear

[51]

understanding of what was intended was conveyed to the brigade officers.

Later in the week, Colonel Murray addressed the division staff and

subordinate commanders. He outlined the Mobile Afloat Force plan, discussed

the environment, and sketched the nature of intended activity. He also

explained that the Marine Corps had developed a basic riverine manual

entitled Small Unit Operations in the Riverine Environment. This document

was obtained by the 2d Brigade for study from the division G3 (assistant

chief of staff for operations), Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. Zastrow.

In early May the Department of the Army had informed the 9th Division

that it would be sent to the Republic of Vietnam, beginning in December. The

assistant division commander, Brigadier General Morgan E. Roseborough,

headed an advance element that left for South Vietnam in late August to plan

deployment of the division.

-

On the 12th of September, Colonel Fulton was informed by General Eckhardt

that a conference would be held on the 17th of September at Coronado Naval

Base, California, and was designated the division representative at the

conference. The conference had been coordinated by Headquarters, U.S.

Continental Army Command, to examine the joint training implications which

would be imposed on the 9th Division and the Army U.S. training base by

participation in the Mobile Afloat Force. General Eckhardt directed Colonel

Fulton to prepare a brief of the Army views on the Mobile Afloat Force that

would include a plan for logistic support. General Eckhardt further asked

that he receive a briefing on the presentation to be made at the conference.

It was also decided that the division support commander, Colonel John H.

Barrier, should accompany Colonel Fulton to Coronado to handle the

logistical aspects.

On 19 September, accompanied by Captain Johnnie H. Corns of his staff,

Colonel Barrier, division G2 and G3 representatives, and a representative of

the division signal office, Colonel Fulton proceeded to Coronado. The

conference was held under the auspices of the Commander, Amphibious Command,

Pacific, Vice Admiral Francis J. Blouin. Navy attendees included

representatives from the Chief of Naval Operations, Commander in Chief,

Pacific Fleet, the Amphibious Training Center, the U.S. Marine Corps, and

Commander, Service Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet. The Army dele-

[52]

gation also included representatives from Continental Army Command

headquarters, U.S. Army Combat Developments Command, Fifth Army

headquarters, and Sixth Army headquarters. The commander of River Assault

Flotilla One, Captain Wade C. Wells, who was to be the U.S. Navy component

commander of the Mobile Afloat Force, his chief of staff, Captain Paul B.

Smith, and the rest of his staff attended. The conference was chaired by

Rear Admiral Julian T. Burke, who had the additional responsibility of

preparing a U.S. Navy doctrinal manual for riverine operations.

Presentations were made of the organization and operations of the two

components as well as the broad problem of command relationships of the

joint force. Afterward several working groups were established to deal with

command and control, joint staff arrangements, training, logistics,

communications, and medical support.

During the conference Captain Wells informed Colonel Fulton that the

River Assault Flotilla One chief of staff and representatives of N-1, N-2,

N-3, and N-4 staff sections, as well as a communications officer, were going

to Vietnam as an advance party in early October. Upon learning that the 9th

Division had an advanced planning element at Headquarters, U.S. Army,

Vietnam, Captain Wells agreed that the two advance elements should be the

basis for co-ordination in Vietnam. Captain Wells and Colonel Fulton also

made informal arrangements to co-ordinate mutual problems that might arise

between the time of the conference and the departure of the 2d Brigade for

Vietnam, which was tentatively scheduled for early January 1967. While there

were no official provisions for direct communications and co-ordination

between the two component commanders of the Mobile Afloat Force, this early

meeting proved extremely beneficial in resolving matters that could have

impaired the entire undertaking.

Returning to Fort Riley, Kansas, Colonel Fulton and Captain Corns briefed

General Eckhardt and his staff on the results of the Coronado conference.

General Eckhardt then designated Colonel Fulton as the executive agent for

the division on riverine matters, and specified that this responsibility

carried with it the designation of commander of the floating brigade and the

U.S. Army component for the Mobile Afloat Force. Colonel Fulton still chose

not to incorporate riverine operations in his training program because of

the great amount of normal training to be accomplished. It was implied,

however, at the conference that there would be a training period in Vietnam

of approximately two to three months during which the Army and Navy

components would be able to train

[53]

their forces for the .joint riverine operations. Nevertheless when

Colonel Fulton informed Lieutenant Colonel William B. Cronin, Commanding

Officer, 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and Lieutenant Colonel Guy I. Tutwiler,

Commanding Officer, 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, of the riverine mission,

they decided as part of their normal training programs to incorporate

techniques and equipment for crossing small rivers.

While at Coronado, Colonel Fulton explored with the commander of the

Amphibious Training School the possibility of conducting a riverine course

for his brigade staff, the battalion commanders and their staffs, and the

brigade supporting unit commanders. This school was a repository of

amphibious doctrine and concepts as well as lessons learned in the MARKET

TIME and GAME WARDEN operations, which were, respectively, the U.S. Navy

offshore and river operations in South Vietnam. All the U.S. Navy advisers

for the Vietnamese river assault groups were trained under Amphibious

Training School auspices. The Navy SEAL (sea-air-land) teams, which were

rotated in and out of South Vietnam, were also trained there. Many of the

school faculty had already completed tours of duty in both the U.S. and

Vietnamese navies. The idea of conducting a riverine course was acceptable

to the commander of the Amphibious Training School, and plans for

instruction were developed through subsequent correspondence between the

brigade and the Amphibious School during the period October through

December. Also it was agreed that the Amphibious Training School would

provide a team at Fort Riley during December 1966 for the purpose of

training selected men from brigade and battalion in techniques of

waterproofing, small boat loading and handling, and combat offloading from

transports. Also included was instruction in water safety techniques that

was to prove immensely valuable once operations commenced.

In early October Colonel Fulton was informed that he would accompany the

division commander to Vietnam on an orientation visit to reconnoiter the

riverine environment and get a preview of the requirements for riverine

operations. The division commander and a small staff left on 9 October for a

three-week visit to Vietnam. Colonel Fulton's arrival coincided with that of

the advance party of the River Assault Flotilla One staff. Colonel Fulton

and Captain Smith, chief of staff of the flotilla, were able to visit and

analyze the proposed training site in the vicinity of Ap Go Dau, adjacent to

the Rung Sat Special Zone, approximately fifteen kilometers south of

Bearcat. Bearcat, ten miles south of Long Binh, was to be

[54]

the 9th Division base instead of Ba Ria, which had been specified in the

original Mobile Afloat Force plan. Bearcat was to be expanded into a base

capable of accommodating the entire division until the 2d Brigade base at Ap

Go Dais could be built. Colonel Fulton and Captain Smith agreed on the site

near Ap Go Dau, and plans were developed by Company B, 15th Engineer

Battalion, to construct the joint training base. A phased training schedule

based on actual combat operations from the new location was also tentatively

agreed upon. The shift of the division base from Ba Ria to Bearcat was to

have no significant effect on the Mobile Afloat Force plan.

Colonel Fulton also visited the Dona Tam construction site, the 7th

Division headquarters of the Army of Vietnam, and General Desobry, senior

adviser of IV Corps Tactical Zone at Can Tho. Discussions centered on

projected operations of U.S. forces in the Mekong Delta. It was especially

fortuitous that Colonel Fulton, General Desobry, and the Senior Advisor, 7th

Division, Colonel John E. Lance, Jr., had been on the faculty of the Army

War College during the period 1962 to 1965. This professional association

proved to be very valuable during the ensuing months as the 2d Brigade

planned for and conducted operations in the Mekong Delta.

While at Headquarters, U.S. Army, Vietnam, Colonel Fulton learned that

the Army had not completed the preparation of the riverine doctrine, a task

assigned to it by MACV Directive 3-66. In discussing the task, Colonel

Fulton found that Major John R. Witherell, the U.S. Army Combat Developments

Command liaison officer, had developed an active interest in the Mobile

Afloat Force plan and had started preparation of a rather detailed

manuscript which dealt with organization and tactics of units as envisaged

by the Mobile Afloat Force planners. At Colonel Fulton's suggestion Major

Witherell agreed to propose to Headquarters, Combat Developments Command,

that it undertake the drafting of a test field manual on riverine

operations. In snaking this recommendation, Major Witherell planned to

furnish his draft manuscript. The meeting proved to be beneficial since

during the Coronado conference the doctrine matter had been explored with

both Navy representatives and Major Donald R. Morelli, the Combat

Developments Command representative at the conference. It was agreed that if

the manual was undertaken, the writing should be done at the Amphibious

Training School at Coronado, the best source of information on riverine

warfare.

[55]

Upon his return to Fort Riley, Colonel Fulton was visited by a

representative from Combat Developments Command who had outlined a manual

based on Major Witherell's manuscript. Colonel Fulton suggested that this be

accepted as the basis for the manual which was to be prepared at Coronado

with representatives from the various Army service schools and Combat

Developments agencies under the leadership of the Institute of Combined Arms

Group, Fort Leavenworth. Colonel Fulton stressed that the manual should be

available when the brigade and battalion staffs departed for South Vietnam

on 14 January 1967. The need for the manual was quite apparent since the

U.S. Marine Corps Fleet Marine Force Manual 8-4, the only doctrinal manual

on riverine operations, dealt with only small boat tactics and did not cover

joint riverine operations.

-

Secretary of Defense McNamara during his October visit to South Vietnam

was briefed on the Mobile Afloat Force, and the need for two additional

river assault squadrons was stressed at that time. The designation river

assault group had been changed to river assault squadron in order to avoid

confusion with the Vietnamese river assault groups. During this briefing it

was emphasized to Mr. McNamara that if the objectives of the MACV campaign

plan were to be achieved, U.S. ground operations in the IV Corps area were

needed to assist the Republic of Vietnam armed forces. It was further

pointed out to Mr. McNamara that roughly 50 percent of the population and 68

percent of the rice-producing area in the Republic of Vietnam were in the

Mekong Delta. In this briefing it was explained that the 9th Division, due

in Vietnam in December 1966 and January 1967, was to be the principal river

ground force, and that the river assault boats needed to provide tactical

mobility would conform to standard U.S. Navy organization structure, with

two assault squadrons of about fifty boats each under command of River

Assault Flotilla One. The Mobile Afloat Force with the two approved river

assault squadrons would provide a good start, but there was a need for at

least two additional assault squadrons by the end of calendar year 1967 in

order to sustain the momentum of the riverine operations. The 9th Division,

now planned with seven infantry battalions and two, rather than one,

mechanized battalions, would require the support of two river assault

squadrons. Two additional battalions from the U.S. 25th Division and the

Australian Task Force would bring the total to

[56]

eleven infantry battalions for riverine operations. No decision was made

by Mr. McNamara on the two river assault squadrons during his visit.

On 21 November General Westmoreland suggested to the Mission Council that

it was feasible to deploy a battalion to Dona Tam in January 1967, and

requested the council's endorsement of this action. Anticipating the

council's concurrence, General Westmoreland directed the planning and

preparation for deployment of a brigade in February 1967 if it was deemed

feasible by II Field Force, Vietnam. By 29 November, Ambassador Lodge had

approved this deployment.

On 1 December, Headquarters, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam,

published a plan for logistical support for the Mobile Afloat Force. This

plan provided for two kinds of support-one for the units based at Dong Tam

and one for the units afloat. The land base commander was assigned

responsibility for the logistical support for Dong Tam, and the mobile

riverine base commander would have responsibility for the mobile riverine

base, while service-peculiar supply would be the responsibility of the

component commander concerned. Saigon was designated as the primary supply

source for the Dong Tam base, with Vung Tau as the alternate, and land lines

of communication were to be used wherever possible. The mobile riverine base

would be supported by Vung Tau, with Saigon as the alternate.

After evaluating the progress of the base construction at Dong Tam, II

Field Force reported on 4 December that it was feasible to support a

battalion at Dong Tam in late February 1967. The planning and liaison

machinery went into high gear early in December. Elements of the 9th

Division would be available for training at the Vung Tau base in early

January. The commander of Naval Forces, Vietnam, had shifted all efforts to

prepare the base for riverine training when the proposed training site at Ap

Go Dau was abandoned in favor of Vung Tau. He recommended liaison between

9th Division and Vietnamese and U.S. agencies. He also asked Admiral Johnson

to provide a suitable support ship at Vung Tau about 7 January and at the

same time to place aboard it one river assault squadron staff and one river

division staff. The commander of River Assault Flotilla One and his staff,

less the advance element, were to leave Coronado in mid-February and a

second river division was to leave in late February.

General Westmoreland directed the commander of II Field Force to prepare

to send an infantry battalion task force from the

[57]

9th Division to Dong Tam, to add forces later to increase it to a

brigade, and to advise hire of the arrival dates. The Commanding General,

U.S. Army, Vietnam, was to support the task forces and Senior Advisor, IV

Corps Tactical Zone, was directed to plan for the provision of Vietnam Army

security forces, co-ordinate Vietnamese and U.S. security arrangements, and

prepare the Vietnamese people for the presence of U.S. troops at Dong Tam.

The first elements of the .9th Division landed at Vung Tau on 19

December, and on 20 December General Westmoreland estimated that the

battalion task force would move to Don- Tam on 25 January following two

engineer companies that were to arrive there on 7 January. He calculated

that strength would increase to brigade level in late February or early

March.

The Mobile Afloat Force, conceived and approved during 1966, was one of

the most important MACV accomplishments of the year. This force eras

expected to play a major role in the control of the delta, not only in a

military sense, but also economically and politically. Further, the entire

delta campaign could well be a key to the success of the combined operations

of the United States and the Republic of Vietnam.

-

Upon completion of. training at Fort Riley at the end of November 1966,

the 2d brigade began preparation for overseas movement. During this time,

selected men from the brigade and battalions were given training by the

Marine Training Team from the Naval Amphibious School. On 3 January, the

brigade commander and staff, the commander and staff of the 2d Battalion,

4th artillery, the commanders and staffs of the 3d and 4th Battalions, 47th

Infantry, and the S-2, 2d Battalion, 47th Infantry, went to Coronado to

attend the ten-day riverine course that had been established at the request

of the brigade commander. The course provided a great deal of useful

information on operations of the Vietnamese river assault groups, U.S. Navy

SEAL teams, Viet Cong intelligence operations in the delta, and the riverine

environment. The ten days gave the commanders and staffs of the brigade's

attached and supporting units the opportunity to concentrate on purely

riverine problems for the first time.

When the course ended on 12 January, the Combat Developments Command

writing group had completed the first draft of Training Text 31-75, Riverine

Operations. Colonel Fulton now learned that although the Navy had provided

advice and consulta-

[58]

tion, it would not formally accept the manual, not would the commander of

River Assault Flotilla One acknowledge the text as a source of doctrine to

which he would subscribe. When agreement had been reached in September that

a manual would fee written, Navy acceptance was tacitly understood, but

since it was not forthcoming the question of agreement on joint procedures

remained. The brigade commander and his officers, however, considered the

training text a sound new source of riverine doctrine and concepts on which

subsequent training in Vietnam could be based. improvement could be made in

the text after the experience of actual operations.

The 2d Brigade officers who had attended the Coronado riverine Course

arrived at Bien Hoa on 15 January and proceeded to Bearcat. Shortly

afterward the remainder of the advance party arrived by air from Fort

Riley-, included were all the squad leaders from the three infantry

battalions, two platoon sergeants and two platoon leaders from each of tile

companies, and all company commanders. The main body was en route by water

from San Francisco tinder the supervision of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas F.

O'Connor, the brigade executive officer. The other officer cadre consisted

of the company executive officers, two platoon leaders from each company,

and the battalion executive officers with small staffs. The purpose of the

large brigade advance party was to give most of the tactical unit combat

leaders battle experience before the main body arrived at the end of

January. To this end the unit advance parties were sent to operate with the

U.S. 1st and 25th Divisions for approximately two and one-half weeks.

The main body debarked at Vting Tau on 31 January and 1 February 1967 and

reached Bearcat on 1 February. On 7 February the 9d Brigade, with the 2d,

3d, and 4th Battalions, 47th Infantry, and 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry,

commenced a one-week operation in the Nlion Trach District of Bien Hoa

Province ,just north of the Rung Sat Special Zone. The 2d Brigade had an

excellent opportunity to shake itself down operationally in a combat

environment and to compensate for the lack of a brigade field training

exercise which it had been unable to conduct at Fort Riley because of the

short training period.

-

During the latter part of ,January the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, an

element of the 3d Brigade, 9th U.S. Division, had begun riverine training

with the advance River Assault Flotilla One ele-

[59]

ments that were aboard USS Whitfield County (LST 1169) , anchored

in Vung Tau harbor. The 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, was to be the first

infantry unit sent to Dong Tam and was to arrive there by the end of

January. It would be followed in training by the 3d Battalion, 47th

Infantry, which was then participating in the 2d Brigade operation in Nhon

Trach.

On 10 February, two companies and the staff of the 3d Battalion, 47th

Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel Lucien E. Bolduc, Jr., left for riverine

training in the Rung Sat Special Zone. The Navy crews with which the

battalion would work had received on-the-job training with the Vietnamese

Navy river assault groups in the delta.

On 15 February, as the brigade was returning from the Nhon Trach

operation to its base camp at Bearcat, an order was received from II Field

Force directing that an entire battalion conduct operations in the Rung Sat

Special Zone beginning 16 February. The order was prompted by a Viet Cong

attack on a freighter navigating the Long Tau, the main shipping channel

connecting Saigon and Vung Tau, on 15 February. It brought to an abrupt halt

the organized training for Colonel Bolduc's battalion, which had

accomplished only three of the scheduled ten days of training; full-scale

combat operations would have to begin. The battalion commander was aboard

USS Whitfield County with two companies when Colonel Fulton talked to

him. Colonel Fulton had already ordered the remaining companies of the 3d

Battalion, 47th Infantry, as well as a direct support battery of the 2d

Battalion, 4th Artillery, into the northern portion of the Rung Sat Special

Zone. Colonel Bolduc's mission was to disrupt enemy activities in the major

base areas of the Viet Cong.

The resulting operation initiated on 16 February 1967 and terminated on

20 March was designated RIVER RAIDER I. It was the first joint operation by

U.S. Army and U.S. Navy units that were later to constitute the Mobile

Riverine Force. The 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, was supported by River

Assault Division 91 of River Assault Squadron 9. (Chart 1)

Joint operations centers were maintained twenty-four hours a day both at

land bases and aboard the APA Henrico, and joint plans were made for

each project. River Assault Flotilla One provided rear area support and

planning assistance for river squadron operations. Squadron 9's assault

division was commanded by Lieutenant Charles H. Sibley, who operated LCM-6's

and a command vessel borrowed from the Vietnam Navy since the squadron's

boats

[60]

had not yet been delivered. Vietnam River Assault Group 26 provided

mine-sweeping support and escorts for movement on narrow and dangerous

waterways.

Particularly important was the support provided by the Infantry Advisor,

Rung Sat Special Zone, Major McLendon G. Morris, USMC, who joined the

battalion command group at the outset of the operation and remained till the

battalion's operations were completed. Major Morris furnished liaison to the

Senior Advisor, Rung Sat Special Zone, at Nha Be and invaluable advice and

assistance. His extensive knowledge of and experience in the zone, his

familiarity with complex fire support procedures, and his ability to get

support on short notice made a significant contribution to RIVER RAIDER I's

Success.

During the operation boats of River Assault Division 91 moved

[61]

troops to and from the barracks ship by ATC at alt hours of the day and

night, delivering them primarily to friendly ambush sites, sometimes to the

battalion land base. They remained in ambush sites at night, and one boat

was normally kept within a fifteen-minute standby range of the land base as

transportation for the platoon-size ground force. Division 91 was called on

a number of times and eras twice instrumental in the capture of sampans and

documents. Its boats patrolled the waterways and gave great flexibility to

the river force.

Use of deception in the conduct of night operations was found very

effective in the Rung Sat Special Zone. Usually a rifle company would be

positioned around the battalion command post during daylight hours. Under

cover of darkness this company would be withdrawn and transported to a new

area where it would establish a perimeter, then move out to place ambushes.

It would then be in a position to begin search and destroy or strike

operations at first light. On one occasion a complete riverine assault, with

artillery fire and radio transmissions, was staged as a feint while troops

remained quietly aboard landing craft that resumed their patrol stations

from which small landings were subsequently made.

For operations on small waterways plastic assault boats and water safety

devices were useful. The battalion used one 27-foot engineer boat and

several 13-man inflatable rubber rafts to advantage, but they, like the

plastic assault boats, offered no protection from small arms fire and their

slow speed and the inevitable bunching of troops made them highly

vulnerable. Water movement was essential, however, since the Viet Cong moved

primarily by sampan; no amount of trudging through mangrove swamps would

outmaneuver an enemy who sought to avoid contact.

While salt water damaged clothing, the need for exchange was not much

higher than in normal field use. The jungle boot stood up well under

protracted use; jungle fatigues were washed overnight aboard the support

ship, and a small direct exchange stock was maintained. The principal damage

was to weapons and ammunition, which salt water corroded. It was necessary

to break down weapons and scrub them with a mixture of cleaning solvent and

oil on each return to the ship. The 7.62 metal link belt ammunition was

frequently so badly corroded that it had to be discarded.

Only essential equipment was carried, the normal load consisting of seven

magazines for the M16 rifle, 200 rounds for the machine gun, and twelve

rounds of 40-mm. grenades. Each squad

[62]

carried 100 feet of nylon rope, a 10-foot rope with snap link per man,

and a grappling hook with 50 feet of line-items that were invaluable in

water crossing operations as well as in detonating booby traps.

Ambushes were found to be most successful on well-traveled waterways.

While airborne infrared devices for detecting people or things by their

difference in temperature from the surrounding area proved valuable in the

sparsely populated Rung Sat Special Zone, they were later less successful in

the heavily populated delta.

The common rule that an ambush should be moved after being tripped did

not always apply to water ambush in the Rung Sat Special Zone. On one

occasion, an ambush was tripped three times in one night, with the result

that seven of the enemy were killed and three sampans and two weapons

captured.

Lack of positions suitable for placing artillery and the great distances

involved produced a large zone in which the enemy was not subject to

friendly fires. The zone was sparsely populated, with friendly civilians concentrated in a few widely dispersed villages separated by areas which the

government warned citizens not to enter. Here the U.S. effort was to keep

the enemy out of areas where troops had already discovered and destroyed

large Viet Cong base camps, factories, munitions, stocks of rice, and other

materiel.

As a result of the experiences in RIVER RAIDER I, Colonel Bolduc

submitted several suggestions that assisted later operations of the Mobile

Riverine Force. He advised that any unit operating in the Rung Sat Special

Zone for other than a limited objective should either be a riverine unit or

receive riverine training at the outset of the operation. Techniques were

relatively simple and easily learned; troops that were well conditioned and

adequately commanded could operate in the zone for a long time without

suffering adverse effects. The longer the operation, the longer the troops

needed to rest and dry out.

Since the enemy scrupulously avoided contact, current tactical

intelligence was of paramount importance. Units operating in the Rung Sat

therefore had to seek intelligence aggressively from all sources and

agencies. Quick translation of enemy documents was also important. In one

case the battalion captured at night from a group of five sampans documents

and maps showing the location of a Viet Cong regional headquarters and

various stops made by the sampan owners along the route they had traveled.

One document showed delivery of arms to specified Viet Con'- units and

compromised an entire Viet Cong signal system. Although the general nature

of

[63]

the contents and their importance was immediately apparent to the

battalion commander, he was obliged to send all the documents to the senior

adviser of the Rung Sat Special Zone. Although he dispatched them

immediately, no translation was received for more than a week too long a

delay to permit timely exploitation. During the last stages of the

operation, all documents were quickly translated by the S-2 and an

interpreter before being sent to higher headquarters so that information

could be acted upon at once.

Airmobility was essential to effective riverine operations; it was

necessary to have a command helicopter capable of carrying a commander, a

fire support co-ordinator, an S-2 intelligence officer, an S-3, and

necessary radio communications. When naval helicopters were used a Navy

representative had to be aboard. When not required for direct control of

operations, the helicopter was fully utilized for reconnaissance and

liaison.

One UH-ID helicopter was placed in direct support of the battalion to

permit resupply and emergency lift of widely scattered troops. The battalion

could fully utilize five transport helicopters and two armed helicopters on

a daily basis for about ten hours. They were needed for airmobile assaults,

positioning of ambushes, troop extractions and transfers, ground

reconnaissance of beaches and helicopter landing zones, checking sampans,

and return to areas previously worked in order to keep the enemy

off-balance. In addition, there was a need for night missions using one

helicopter with two starlight scopes and two armed helicopters in order to

interrupt Viet Cong sampan traffic along the myriad waterways. Finally,

airlift was necessary to make use of any substantial finds in the area of

operations. Without helicopter transport, it was frequently necessary to

destroy captured materiel-munitions, cement, large rice stores-because it

could not be moved.

Fire support was diverse and highly effective. Artillery fire support

bases were established with as many as three separate artillery batteries

(105-mm., towed) employed at the same time from different locations. Naval

gunfire was used continuously throughout the operation, including indirect

fire of several destroyers and the direct and indirect fire of weapons

organic to boats of Division 91, U.S. Navy, and River Assault Group 26,

Vietnam Navy. Other fire support was provided by tactical air, and by U.S.

Air Force, Army, and Navy fixed-wing and helicopter gunships.

Fire support presented a number of co-ordination and clearance problems.

The main shipping channel was patrolled constantly by U.S. Navy river patrol

boats and aircraft which, because of daylight

[64]

A WET BUT PEACEFUL LANDING

traffic in shipping, required close control to prevent damage to U.S. or

South Vietnamese forces and equipment. An additional problem was that in

some areas clearance from the government of Vietnam was required for each

mission. U.S. ground clearance for indirect fire was co-ordinated by the

artillery liaison officer. Getting government clearance at first proved to

be time-consuming. Requests had to be submitted to the senior adviser of the

zone at Nha Be. Any aircraft in the area of operation would cause a cease

fire in the entire Rung Sat. A zonal clearance system was worked out by all

parties concerned and proved highly successful. It consisted of a circle

with a radius of 11.5 kilometers drawn on the fire support map using the

fire support base (battery center) as the center. The circle was then

subdivided like a pie into eight equal parts or zones and each was numbered

from one to eight. Thereafter, to obtain clearance all that was required was

to ask permission to fire into the zone in question. Artillery and mortar

fire could thus be applied to the zone or zones where it was needed and

withheld from the rest of the area.

Troops on combat operations in the Rung Sat Special Zone

[65]

A WET BUT PEACEFUL LANDING

traffic in shipping, required close control to prevent damage to U.S. or

South Vietnamese forces and equipment. An additional problem was that in

some areas clearance from the government of Vietnam was required for each

mission. U.S. ground clearance for indirect fire was co-ordinated by the

artillery liaison officer. Getting government clearance at first proved to

be time-consuming. Requests had to be submitted to the senior adviser of the

zone at Nha Be. Any aircraft in the area of operation would cause a cease

fire in the entire Rung Sat. A zonal clearance system was worked out by all

parties concerned and proved highly successful. It consisted of a circle

with a radius of 11.5 kilometers drawn on the fire support map using the

fire support base (battery center) as the center. The circle was then

subdivided like a pie into eight equal parts or zones and each was numbered

from one to eight. Thereafter, to obtain clearance all that was required was

to ask permission to fire into the zone in question. Artillery and mortar

fire could thus be applied to the zone or zones where it was needed and

withheld from the rest of the area.

Troops on combat operations in the Rung Sat Special Zone

[65]

-

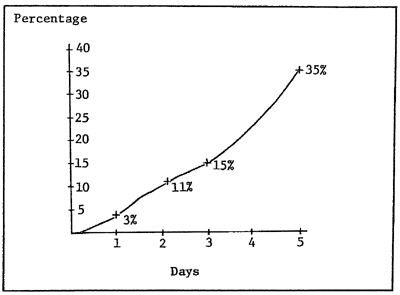

Diagram 4. Foot disease incident rate.

were continually in mud and the salty, dirty water could not be used for

bathing. Certain measures were therefore taken to safeguard the health of

the troops. Men stayed on combat operations for forty-eight hours at a time

and were then sent to the troopship in the Vung Tau area where adequate

shower facilities were available and every man had a bunk for the night. All

companies received instructions on care of the feet, which included thorough

washing, drying, and daily inspection of the feet by medics. The battalion

surgeons carried out frequent inspections and all cases of dermatophytosis

were treated with fungicidal ointments and powders. (Diagram 4)

An experiment to determine the efficiency of a silicone ointment was

carried out with seventy-six soldiers who used the ointment daily. During

some twenty days, six cases of immersion foot occurred, four of them on men

who used the silicone. It was found that the system of rotating troops for a

forty-eight-hour drying out period and conducting inspections of feet to

insure necessary treatment of conditions as soon as they arose was of far

greater benefit than use of the preventive ointment.

Positioning mortars ashore in the Rung Sat was difficult and

time-consuming because of lack of firm ground, and was done only

[66]

in the area of the battalion forward command post, which was seldom

moved. For support of wide-ranging operations more mobility than this

semipermanent location of the mortars was required. During RIVER RAIDER I,

two 81-mm. mortars were installed in the forward portion of an LCM. The

mortar boat was nosed into the bank, engines kept running to advance or back

in accordance with the tide, and steadied against the current by quartering

lines running from the stern forward and outward at an angle of about 30

degrees to the bank on either side of the bow ramp. Most of the mortar crews

were used to establish local security on the bank. This arrangement

permitted a high degree of mobility, rapid positioning for firing, minimum

wasted effort by the gun crews, and an ample supply of ammunition close at

hand. The mortar boat was used both day and night throughout the operation,

and provided flexible, mobile fire support for all types of maneuver.

The major operational success of RIVER RAIDER I was the capture of

substantial stores of water mines and the destruction of facilities for

constructing water mines. It is highly probable that these losses suffered

by the Viet Cong account in part for the very limited use of water mines

against riverine forces during later operations in the northern Mekong Delta

as well as in the Rung Sat Special Zone.

After RIVER RAIDER I, the 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, took up

operations in the Rung Sat Special Zone, making use during April and early

May of the experiences of the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and improvising

other techniques. During this time so-called Ammi barges were obtained from

the Navy for use alongside the LST of River Flotilla One. With this type of

ponton, rope ladders were not needed and the training time for riverine

troops was drastically reduced. The Ammi barges provided as well some much

needed space for cleaning and storage of ammunition, crew-served weapons,

and individual equipment.

[67]

Page created 29 May 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents