- Chapter IV:

Initial Delta Operations

When the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, was sent to Dong

Tam in January 1967, the Headquarters, 3d Brigade, U.S. 9th Infantry

Division, also went to Dong Tam to direct construction of the base and to

conduct operations in Dinh Tuong Province. The 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry

(Mechanized), was stationed at Tan Hiep, an airstrip about eight kilometers

northeast of My Tho along Highway 4. The 3d Brigade conducted the first of a

series of operations in late February 1967; these operations were usually

limited to one battalion and one or two companies of another battalion

because so many troops were needed to protect the construction work at Dong

Tam Base.

Implementing earlier planning, General Westmoreland decided to move

Headquarters, 2d Brigade, to Dong Tam so that it would become operational at

that location on 10 March. The 3d Brigade was moved north to Tan An, the

capital of Long An Province, with the mission of conducting a consolidation

operation to assist the pacification program in the southern portion of the

III Corps Tactical Zone. With the arrival of Headquarters, 2d Brigade, at

Dong Tam, the brigade began a demanding 90-day period of performing four

separate but related tasks: the defense and construction of the Dong Tam

Base; limited offensive operations in Dinh Tuong and Kien Hoa Provinces;

operations in the Rung Sat Special Zone to protect the shipping channel; and

planning with Task Force 117 to move aboard the Navy ships.

Conducting operations in Dinh Tuong Province was to prove as important in

the seasoning of the battalions of 2d Brigade as was the riverine training

in the Rung Sat Special Zone. The threat posed to Dong Tam by the Viet Cong

514th Provincial Battalion, the 263d Main Force Battalion, and local force

sapper and infantry companies and guerrillas demanded a varied offensive

campaign to protect the base as well as to reduce the Viet Cong influence.

Although Dinh Tuong Province was bordered on the south by

[68]

the My Tho River, the limited navigability of smaller streams greatly

limited boat movement within the province. Most canals were blocked by the

debris of destroyed bridges or by earthen dams erected by the Viet Cong to

prevent their use by civilians or military forces. Therefore, although the

brigade was scheduled for a riverine role, it was to carry on between March

and June a variety of operations common to all U.S. infantry units in

Vietnam. These included throwing a cordon around hamlets and searching them

in the hope of capturing members of the local Viet Cong political

organization and guerrilla squads and platoons; brigade and battalion

reconnaissance in force operations; and extensive patrolling. Troops moved

by helicopter, boat, wheeled and tracked vehicles, or on foot. During the

wet season the brigade operated in the Dong Tam area by boat and helicopter

chiefly. When aircraft were not available, wheeled vehicles could carry

troops on Highway 4 to find the enemy near suspected Viet Cong bases. The

troops then moved on foot into the operational areas to the north and south

of the road.

During March and April the brigade commander and staff, assisted by the

senior U.S. adviser of the 7th Vietnam Army Division, Colonel Lance,

assembled good intelligence covering Dinh Tuong and Kien Hoa Provinces. In

addition, through the U.S. senior adviser to IV Corps, General Desobry,

arrangements were made for periodic briefings of the brigade staff by the

G-2, IV Corps advisory staff. This information was used in a series of

cooperative operations undertaken by the 2d Brigade with the 7th Vietnam

Army Division. These were to provide beneficial combat experience for the

brigade before it embarked as the Army component of the Mobile Riverine

Force.

The diverse tasks of the brigade seldom permitted more than two infantry

battalions to be used in offensive operations. Thus in covering large base

areas without exact intelligence of enemy locations, participation of

additional forces was co-ordinated with the 7th Vietnam Army Division to

search thoroughly and to block escape routes. The Commanding General, 7th

Vietnam Army Division, approved of such operations because they permitted

him to deploy small forces into Viet Cong base areas, for which he would

otherwise have been obliged to use more Vietnamese troops than he could

spare from their security missions. Throughout the experience of the Mobile

Riverine Force, it was to prove necessary to obtain additional troops,

whether they were other U.S. units, Vietnam Army units, or Vietnamese

marines, to augment the two

[69]

battalions routinely operating within the Mobile Riverine Force.

During

the period 15 February-10 May, the 2d Brigade, although physically based at

Dong Tam, conducted infantry operations with the 3d and 4th Battalions, 47th

Infantry, in the Rung Sat Special Zone and southern Bien Hoa Province. While

the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, was located in the Rung Sat during February

and March, the 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, was used in the southern

portion of Bien Hoa Province, south of Bearcat and bordering the Rung Sat.

The boats of the Navy's River Assault Squadron 9 supported Army operations

in the Rung Sat during this period.

At the same time active co-ordination and planning for the Mobile Afloat

Force was begun by the 2d Brigade staff with the advance staff of River

Assault Flotilla One. General Eckhardt assigned Lieutenant Colonel John R.

Witherell, who had been the Combat Developments Command liaison officer to

the G-3 Section, U.S. Army, Vietnam, to 2d Brigade. As a major, Colonel

Witherell had initiated the first outline draft of the riverine doctrine

manual. He was made the deputy for riverine planning for the 2d Brigade,

augmenting the brigade staff. At this time, Lieutenant Colonel James S. G.

Turner, U.S. Marine Corps, was placed on duty with Headquarters, 9th

Division, by the Commandant of the Marine Corps as an observer and liaison

officer for riverine operations. At the request of the brigade commander,

Colonel Turner was placed on special duty with the brigade staff. Colonels

Witherell and Turner proved to be valuable additions because the brigade

staff was involved in planning for and conducting daily operations of the

two maneuver battalions, including Dong Tam Base defense operations, as well

as in formulating plans to establish the brigade at Dong Tam. In the early

draft plans prepared by Colonel Witherell, the term Mekong Delta Mobile

Afloat Force was dropped and the title Mobile Riverine Force was formally

adopted.

As of mid-January, two APB's, Colleton and Benewah, were

scheduled to arrive in Vietnam during May or June 1967. The two ships would

provide only 1,600 berthing spaces for Army troops. When troop space for

artillery support, base security forces, and the brigade staff was

subtracted, there would remain spaces for a combat force of approximately

one reinforced battalion. It was considered essential to increase the combat

strength of the brigade to at least two battalions. Since only two APB's

were available, it

[70]

NON-SELF-PROPELLED BARRACKS SHIP

was recommended by the 2d Brigade that a towed barracks ship, an APL,

with a berthing capacity for 660 troops be made available. This

recommendation was forwarded through division to the commander of II Field

Force, who, in turn, requested the commander of the naval force in Vietnam

to make the APL available. He proposed that if the APL was diverted, Navy

men be provided to operate and maintain only the equipment peculiar to the

Navy and that Army troops be required to perform all other support functions

such as cleaning, preventive maintenance, messing, laundry service, and

security. This proposal was satisfactory to the Army and APL-26 was diverted

to Dong Tam in May, along with two sea-going tugs to move the barracks ship.

An additional 175 berths were provided by building hunks on the top side of

the APL under a canvas canopy.

Frequent co-ordination meetings were field with Captain Wells aboard his

flagship at Vung Tait. During the last two weeks of March Colonels Witherell

and Turner moved aboard the flagship to participate with the Navy staff in

the development of a Mobile Riverine Force standing order. The brigade

operations officer, Major Clyde J. Tate, continued to concentrate on the

current

[7]

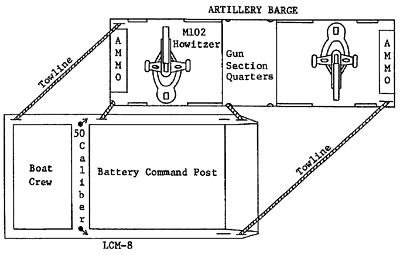

ARTILLERY BARGE

brigade operations. Colonel Fulton felt that the Mobile Afloat Force plan

had not provided effective artillery support for the Mobile Riverine Force

operations. The armored troop carriers were to lift the 105-mm. howitzers

and their prime movers. The artillery battalion, after being moved by water,

would debark at a suitable place along the river and establish firing

positions. Terrain reconnaissance conducted during his October 1966 visit

had convinced Colonel Fulton that the off-loading of the prime movers from

an ATC as provided for in the plan would greatly restrict operations because

of the varying tides of four to thirteen feet and the steepness of the river

banks. Consequently, the Commanding Officer, 3d Battalion, 34th Artillery,

Lieutenant Colonel Carroll S. Meek, began to experiment with barge-mounted

artillery. He placed a 105-mm. howitzer on an Ammi barge, using cleats and

segments of telephone poles against which the trails of the howitzer rested.

Successful firing demonstrated the feasibility of this method. By use of

aiming stakes placed ashore routine fire support could be provided from the

barges anchored securely against the river bank.

During these experiments, the Deputy Commanding General,

[72]

Diagram 5. Artillery barge towing position.

U.S. Army, Vietnam, Lieutenant General Jean E. Engler, placed a liaison

officer from the G-4 Section on temporary duty with the brigade. This

officer's sole mission was to procure special equip ment requested by the

brigade, thus eliminating the procedure of requesting items through normal

channels and greatly facilitating the acquisition of equipment. After

Colonel Meek's initial firing experience with the barge-mounted artillery,

the liaison officer was asked to arrange fabrication of an experimental

artillery barge. The work was done in a few weeks at Cam Ranh Bay, where

small pontons were welded together into an artillery barge. The barge was

then towed down the coast and brought up the Mekong River to Dong Tam by a

commercial ocean-going tug. Further firing experiments proved the barge

unsatisfactory in that the high bow of the ponton was nearly perpendicular

to the surface of the water, making it hard to maneuver and tow, especially

against the current, tide, or prevailing wind. The barge was redesigned so

that it floated lower in the water and had a sloped bow, and the design was

forwarded by the G-4 liaison officer to Cam Ranh Bay. As a result of

successful experiments with the new design, six barges were fabricated, each

barge to accommodate two tubes of 105-mm. howitzer, M102. (Diagram 5) Each

barge was to be towed by an LCM-8 throughout the areas in which the Navy

assault craft supported Army forces. The decision to develop the artillery

barges was the most important equipment decision made by the Army for the

[73]

ARTILLERY FIRES FROM BARGES ANCHORED ON RIVER BANK

Mobile Riverine Force because the barges provided effective artillery

support at all times. Had General Engler not had the foresight to furnish

liaison and to make special arrangements to obtain unique equipment, the

initial effectiveness of the Mobile Riverine Force would have been greatly

impaired.

Also during the March-April period, Colonel Fulton decided that there was

not enough helicopter landing space aboard the ships of the river force.

Each APB had one helicopter landing pad, and the LST could accommodate the

landing of one helicopter. Through the same expedited development process

used for the artillery barges, a helicopter landing barge was provided that

could accommodate three UH-1 helicopters and would have a refueling capacity

for the helicopters of 1,500 gallons of JP-4. This barge would be towed by

an LCM-8 of the Army transportation boat company.

As more U.S. Navy craft arrived in Vietnam and the initial training was

completed, River Assault Flotilla One elements were sent from the Vung Tau-Rung

Sat Special Zone training area into Dinh Tuong Province. On 10 April the

first river assault division

[74]

HELICOPTER BARGE

moved to Dong Tam with 18 ATC's, 1 CCB, and 2 monitors and immediately

began waterborne operations with the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, which had

also left Rung Sat Special Zone for Dong Tam. Although these operations on

the Mekong River were small in scale during the month of April, the men soon

learned that unlike the rivers of the Rung Sat Special Zone, where obstacles

were few, the delta waterways had many man-made obstructions such as low

bridges, fish traps, and earthen blocks on canals.

During April a small staff group of River Assault Flotilla One went to

Dong Tam to work closely with the 2d Brigade staff in developing the final

plans for Mobile Riverine Force operations, which were to begin on 2 June.

The first embarkation was to include the brigade headquarters and staff; 3d

Battalion, 34th Artillery; Company C, 15th Engineers; and the division

support elements. In the final planning phase for this embarkation it was

decided that a larger supply LST would be needed to provide an additional

375 U.S. Army berthing spaces. Originally two class 542 LST's were scheduled

as the logistics support ships to rotate between Vung Tau and the riverine

base. Since the 542 class is

[75]

much smaller and provides less billeting space, a request was made to

River Assault Flotilla One for one of the larger 1152 class LST's. Again,

the Navy accommodated the Army request. Acquisition of the larger LST was to

prove very advantageous in that the entire brigade aviation section, which

included four OH-23 helicopters, and the maintenance section were placed

aboard the LST and were operated from the flight deck. Limited air resources

were now available for combat operations regardless of the remoteness of the

location of the mobile riverine base from 9th Division support.

Both the brigade headquarters and the infantry battalions were internally

reorganized so that all equipment not necessary for riverine operations

could be left at the Dong Tam base under the control of unit rear

detachments. Spaces for jobs not needed by the Riverine Force, such as for

drivers and mechanics, were converted to spaces with shipboard and combat

duties. The combat support company of each battalion was reconstituted into

a reconnaissance and surveillance company. Men assigned to spaces whose

function was not required in the Mobile Riverine Force were placed in these

two companies and thus two additional rifle platoons were created in each of

the two battalions. When these two platoons were added to the reconnaissance

platoon normally found in the combat support company, a fourth rifle company

for each battalion was organized. This arrangement was to prove most

satisfactory because it provided for base defense and other security

missions and at the same time left three companies for battalion tactical

operations.

While planning of the riverine organization of the infantry battalions

was taking place, in April and May the battalions were actually conducting

land operations. The 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and 3d Battalion, 60th

Infantry, were increasing their proficiency in airmobile operations and

learning to work with the officials of Dinh Tuong Province and Army of

Vietnam division forces.

On 1 April 2d Brigade forces made a raid into northern Kien Hoa Province

on the My Tho River south of Dong Tam, using barge-mounted artillery. During

darkness, one battery was moved west on the river from the land base,

followed closely by infantry mounted in ATC's. Once opposite a manned

station of a Viet Cong communications liaison route, the artillery poured

surprise, direct fire into the target area. To protect a Ham Long District

company, which had occupied a blocking position south of the target, time

[76]

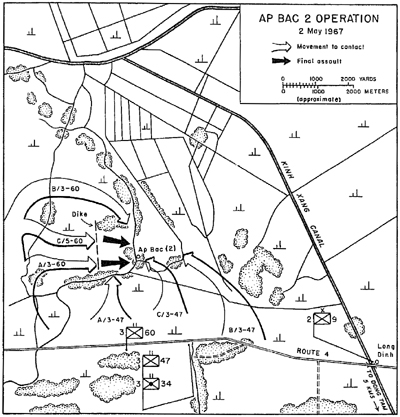

MAP 4

fuzes were used. Immediately after the artillery fire, infantry troops

landed and swept through the station. The artillery then anchored against

the north bank of the river and prepared to provide indirect fire support.

The raiders captured enemy ammunition and a portion of the labor force of

the enemy communication-liaison platoon.

On 2 May the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and 3d Battalion, 60th

Infantry, participated in the 2d Brigade's heaviest fighting to date. The

target of the brigade assault was the 514th Local Force Battalion in the Ap

Bac 2 area, which had been identified by the commanding general of the 7th

Vietnam Army Division as a normal operating area for the Viet Cong. (Map

4)

The ground over which the battle would take place was alternately rice paddy

and thick patches of vegetation with heavy foliage along the streams and

canals. The brigade plan was to conduct an airmobile operation in

[77]

co-operation with the 7th Vietnam Army Division. On the morning of the

operation, however, shortly after the scheduled time for the airlift of the

first company, the brigade was notified that no airmobile company was

available. The brigade commander decided to send the unit by truck, a move

requiring approximately two hours. At the same time the brigade forward

command post elements moved north by ATC's on the Kinh Xang Canal to set up

a post at Long Binh. The 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, truck convoy was

followed by the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, on the same route. The

companies of both battalions were off-loaded facing north from Highway 4.

By 0830 both battalions were moving north to their first objectives.

Elements of the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, on the west met no resistance.

Units of the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, moved forward cautiously during

the morning, covering about 1,500 meters and receiving light sniper fire. At

approximately 1250 both Companies A and B, 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry,

encountered the enemy. Company A came under heavy automatic weapons fire

immediately after emerging from a wood line; it deployed in an attempt to

move against the enemy position, but was hampered by heavy undergrowth that

made it difficult to see the enemy firing positions. The company sought to

improve its position, and called in fire support, including artillery fire,

gunships, and eventually three air strikes on the enemy position.

About 1300, Company B, 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, was placed under

operational control of the commander of 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and

directed to establish a blocking position north of the enemy location. At

the same time Company A, 3d Battalion. 60th Infantry, and Company C, 5th

Battalion, 60th Infantry, were ordered to close enemy escape routes on the

west. Companies B and C, 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, were ordered to block

northeast of the position of Company A, 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry.

Company C, 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry, a mechanized company, using

full-tracked armored personnel carriers, moved through inundated areas which

had been thought impassable to occupy a position west of the enemy. Company

C, 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry, and Company A, 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry,

then made the final assault from the west into the enemy position. Company

C, 5th Battalion, 60th Infantry, greatly enhanced the firepower of the

assault by employing the .50-caliber fire of its full-tracked armored

carriers in the assault line. The organic infantry attacked on foot

alongside the carriers. The enemy resisted with heavy rifle

[78]

and automatic weapons fire. Company A, 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, on

the right flank of the assault, charged into the southern line of bunkers,

and finally overran it. Seeing that their line was broken, many Viet Cong

tried to escape to the east but were killed or wounded as both attacking

companies made their final assault into the bunker line. By 1820 enemy

resistance was overcome.

Although not a riverine operation, the action at Ap Bac contributed to

the brigade tactical experience which was later carried into riverine

operations. In developing operational plans, the brigade staff recognized

that tactical control measures have to provide for maximum flexibility in

controlling the maneuver of units. If the original plan cannot be executed,

there must be sufficient latitude to redirect the effort of the

participating units according to the control measures previously issued.

Check points, a series of intermediate objectives, and an area grid system

provide flexibility for redirection of units and shifting of boundaries and

fire coordination lines.

The Ap Bac operation included in the words of an infantryman

"finding, fixing, fighting, and finishing" the enemy. Through the

use of simple control measures, units of the two battalions were moved into

blocking positions to cut off enemy routes of withdrawal, and other units

were maneuvered into assault positions. When this maneuver was combined with

use of both air and artillery supporting force, the enemy had to remain in

his position or expose himself in an attempt to withdraw.

The operation made it clear that units must be prepared to bring in

artillery and air support as close as possible to the front lines. Each

battalion commander used an observation helicopter to co-ordinate fire in

close support of his unit. The infantry units, once having found the enemy,

had to be prepared through fire and maneuver to conduct a co-ordinated

assault against the enemy positions. In this engagement, by the use of close

supporting artillery fire; the infantry units were able to launch a co-ordinated

attack which overcame the enemy.

Mechanized infantry was used most successfully at Ap Bac. The unit

commander had to search for routes through very swampy and marshy areas.

Once his armored personnel carriers (APC's) were deployed, he dismounted his

infantry and moved APC's and infantry in a forward rapid assault on the

enemy. The volume of fire delivered by the APC's into the bunker -line,

along with high explosive and white phosphorous rounds of artillery, enabled

the infantry to overcome the enemy in bunkers and foxholes. Once

[79]

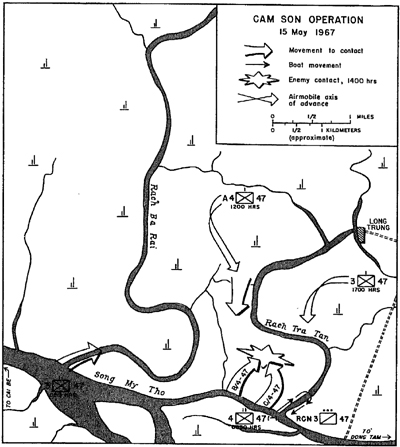

MAP 5

fire superiority had been established, the assault was executed with few

American casualties.

General Thanh, commanding the 7th Vietnam Army Division, monitored the

course of the 2 May battle with interest. By midnight the intelligence

staffs of the brigade and 7th Vietnam Division had estimated that the enemy

consisted of the 514th Local Force Battalion with two companies and its

heavy weapons. An enemy attack launched at dusk of 2 May on the command post

of the 3d Battalion, 60th Infantry, just south of Highway 4, appeared to be

the rest of the 514th Local Force Battalion trying to relieve pressure on

its units north of Highway 4. On the strength of this estimate, General

Thanh sent a Ranger battalion on 3 May into the area which he

[80]

ARMORED TROOP CARRIERS IN CONVOY BATTLE LINE

considered the most probable location to which the enemy would flee. His

Rangers encountered and attacked an estimated company of the 514th Local

Force Battalion during the afternoon. The casualties inflicted upon the

514th by the U.S. 2d Brigade and the 7th Vietnam Army Division severely

reduced its combat effectiveness. Reports received later suggested that the

263d Main Force Battalion was forced to undertake training of new recruits

and operational tasks of the 514th Battalion because of the losses in men

and weapons.

On 13 May the 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, completed operations in the

Rung Sat Special Zone and joined the brigade at Dong Tam. Colonel Tutwiler's

battalion participated in its first major riverine operation in the Dona Tam

area on 15 May as the 2d Brigade conducted the first of several operations

in the Cam Son Secret Zone. (Map 5) The Cam Son area was considered one of

four major Viet Cong bases in Dinh Tuong Province by the intelligence staffs

of both the province and 7th Vietnam Army Division. The operation of 15 May

relied entirely on intelligence provided by these Vietnamese organizations.

[81]

The brigade plan was to search the southern area of Cam Son along the

Rach Ba Rai and Rach Tra Tan streams and to capture or destroy the Viet

Cong, their supplies, and their equipment. A forward brigade command post

was established approximately two kilometers north of Cai Be, and a

barge-mounted artillery base was established on the southern bank of the My

Tho River, five kilometers southeast of the mouth of the Rach Ba Rai. The

two infantry battalions were supported by 22 ATC's, 2 monitors, and 2 CCB's

of River Assault Flotilla One. Commander Charles H. Black, the operations

officer of River Assault Flotilla One, joined the brigade command group and

co-ordinated the support of the Navy assault craft.

The operation began at 0815 when the 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, landed

from assault craft at the mouth of the Rach Ba Rai and began to search

northeast along the stream. At 0830 the 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, landed

two companies from assault craft on the north bank of the My Tho River

approximately halfway between the mouths of the Rach Ba Rai and the Rach Tra

Tan. At 1200 Company A, 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, was airlifted from

Dong Tam, where it had been in readiness as a reserve, and was landed three

kilometers north of the river on the west side of the Rach Tra Tan to act as

a blocking force against any enemy encountered. After landing the Army

troops, the boats of the Navy task force proceeded to blocking stations

along the waterways.

At 1400 Companies B and C of the 4th Battalion, 47th Infantry, met a Viet

Cong force equipped with small arms, light machine guns, and rocket

launchers. Company A maneuvered south and met the enemy within two

kilometers of the My Tho river. Although Companies B and C made little

progress in moving against the enemy fire, artillery and close air support

maintained pressure on the Viet Cong.

In an effort to move more troops to the northeast and rear of the Viet

Cong force, the Reconnaissance Platoon, 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, was

moved by ATC into the Rach Tra Tan. When the low tide and enemy antitank

rockets prevented the assault craft from penetrating upriver beyond enemy

positions on the banks, the platoon was withdrawn.

By 1630 it became apparent that some enemy forces were escaping by moving

to the northeast, away from both Companies B and C, which were moving from

the south, and from Company A, which was moving from the northwest. At this

point Colonel Fulton directed Colonel Bolduc to move one of his companies by

helicopter

[82]

to establish a blocking position northeast of the battle. This was

accomplished by 1700, but the company failed to find the enemy, and by 2000

all contact with the Viet Cong was lost.

This fight called attention to the limitations imposed upon maneuver or

assault craft during low tide and the importance of artillery and close air

support against an enemy in well-prepared bunkers and firing positions.

Although most American casualties did not require evacuation because their

wounds were superficial, both Army and Navy were concerned -by the

vulnerability of men aboard the assault craft to rocket fragments. The

Mobile Riverine Force was to find vulnerability of troops aboard assault

craft one of its continuing problems.

On 18 and 19 May the 2d Brigade moved a forward command post by motor

convoy north of Cai Be in western Dinh Tuong Province to control the

operations of 3d Battalion, 47th Infantry, and 3d Battalion, Goth Infantry.

To reduce the distance the supporting helicopters would have to fly, River

Assault Flotilla One assault craft moved both battalions by water thirty-six

kilometers west of Dong Tam to landing sites on the north bank of the My Tho

River. With the infantry battalions positioned within seven kilometers of

the center of the target area, one airmobile company was able to insert each

battalion rapidly into the area. In the event of substantial fighting the

helicopters could turn around quickly in building up forces.

During this operation the battalions of the 2d Brigade met few of the

Viet Cong, but the brigade command post was attacked by mortar, recoilless

rifle, and machine gun fire during the early hours of 19 May. A ground

attack was thwarted when the Reconnaissance Platoon, 3d Battalion, 47th

Infantry, led by Second Lieutenant Howard C. Kirk III intercepted enemy

movement toward the western perimeter of the position; assisted by

artillery, gunships, and an armed illumination aircraft, the reconnaissance

platoon broke up the attack.

Throughout the month of May, a maximum effort was made to establish

procedures for close co-operation between Army and Navy elements. Colonel

Fulton and Commander Black agreed that the helicopter was invaluable for

command and control of riverine operations. Finding important terrain

features is a very difficult task for the commander on the surface, but a

simpler task for the airborne commander. Foot troop and assault craft

maneuver were facilitated by information furnished by the airborne command

group. During darkness and in marginal flying weather, the com-

[83]

mand and communications boats were valuable to brigade and battalion

commanders in their forward positions. The combined use of command

helicopters and command boats by brigade and battalion commanders permitted

close supervision and control of the Mobile Riverine Force in combat.

The operations of the 2d Brigade in Dinh Tuong Province from March

through May had already provided invaluable operational experience. All of

the brigade's units had met and withstood the enemy; thus a feeling of

confidence had been engendered in commanders and men. Of even greater

importance, however, was the displacement of Viet Cong units from the Dong

Tam area to the western portion of Dinh Tuong Province, from which the enemy

could not readily launch a large ground attack on the base. The 2d Brigade

had become operational at Dong Tam on 10 March, only seventy-two hours after

an engagement involving a platoon of the 3d Brigade and a larger Viet Cong

unit less than eight kilometers from the base, and forty-eight hours after

the enemy launched an attack on Dong Tam with recoilless rifles and mortars.

In the next ninety days the enemy made one successful sapper attack that

damaged a construction vehicle outside the camp and an American patrol

ambushed an enemy force of platoon size three kilometers west of the base.

To prevent enemy fire and ground attack on the base, a patrolling system was

executed by the base defense battalion, using division artillery radar.

Patrols were made on foot, by tracked and wheeled vehicles, by boat, and by

helicopter, and were sent out by day and by night.

Offensive operations came to be guided by knowledge of the habits of the

Viet Cong, who made use of certain areas and routes for bases and for

communication, liaison, and supply. Although information provided by the

Vietnam Army division and province intelligence agencies seldom arrived in

time to serve as the basis for an attack, it was useful in tracking the

enemy's routes, bases, and length of stay in bases. It permitted a rough

guess as to when a Viet Cong battalion would be in any one of the four major

Dinh Tuong base areas at a given time. Operations could be conducted against

one or more bases on a priority basis. By co-operation with the Vietnam Army

and using economy of force, the brigade could enter the first priority base

area with most of two battalions, the Vietnamese forces could enter the

second priority area, and the brigade would use a small force to reconnoiter

a third base area. Helicopter transport was essential and air cavalry

support highly desirable. It was not, however, until May that a portion of

Troop

[84]

D, 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry, was used by the 2d Brigade.

By the end of May, the brigade had found the enemy in three of the four

Dinh Tuong base areas on many occasions and had contributed to a period of

relative security for the men attempting to complete construction of the

Dong Tam Base as well as for the province itself.

During early April it had become apparent that the Navy's concept of the

employment of the Mobile Riverine Force differed slightly from the original

Mobile Afloat Force concept. Captain Wells contended that the force should

act as a separate force, divorced from 9th U.S. Division operations and

control, with deployments deep into the delta. A period of intensive

discussions between the component commanders ensued. Differences were not

resolved until the preparation of a wet and dry season campaign plan for the

Mobile River Force as well as a draft letter of instruction from the 9th

U.S. Division commander to the brigade commander. This letter was prepared

by the brigade staff and carried to the commander of the 9th Infantry

Division, General Eckhardt, with the recommendation that it be issued by

Headquarters, 9th U.S. Division, to the Mobile Riverine Force Army component

commander.

General Eckhardt accepted the draft letter and draft campaign plan and

personally took them to Captain Wells, who, as the commander of River

Assault Flotilla One and Task Force 117, the operational designation of the

Navy component of the riverine force, accepted both. These two documents

adhered to the original Mobile Afloat Force plan for operation of the river

force in conjunction with the other 9th U.S. Division elements in the

southern III Corps Tactical Zone and in the northern portion of the IV Corps

Tactical Zone north of the Mekong River.

The opinion of the Navy component commander that operations should be

conducted exclusively in IV Corps was not supported by Headquarters, MACV,

Planning Directive Number 12-66, dated 10 December 1966, entitled Command

Relations for Riverine Operations in South Vietnam. Essentially, this

document placed Army forces conducting riverine operations in III and IV

Corps Tactical Zones under the operational control of the Commanding

General, II Field Force, with a stipulation that he might exercise

operational control through designated subordinate U.S. Army headquarters.

The commander of U.S. Army, Vietnam,

[85]

would exercise command, less operational control, of all U.S. Army units

engaged in riverine operations. Similarly. Navy riverine forces were placed

under the operational control of the commander of Naval Forces, Vietnam, and

under the command, less operational control, of Commander in Chief, Pacific

Fleet.

The planning directive recognized the unique command arrangements

peculiar to the Mobile Afloat Force concept. This was not to be a joint task

force and the specific command relationships had not been planned under the

original concept. The planning directive took note of the fact that

"the conduct of riverine operations by Army and Navy forces is a new

concept which will require the utmost coordination and cooperation by all

concerned. As operations are conducted and lessons learned, command

relations will be revised as necessary to insure effective and workable

arrangements." There was to be no single commander of the Mobile

Riverine Force.

The MACV document stipulated that the base commander for all bases,

whether ashore or afloat, would be the senior Army commander assigned. It

further stipulated that the relation between the Army and Navy units

stationed on both Army and Navy bases would be one of co-ordination and

mutual support, with the Navy providing its appropriate share of forces for

local base defense, including naval gunfire support and protection against

waterborne threats. Operational control of Navy units in these circumstances

was to be exercised by the base commander through the Navy chain of command.

Command relationships for riverine operations were further defined as

commencing when troops began embarking on assault craft to leave the base

and ending when troops had debarked from the boats upon return to the base.

During riverine operations, the Army commander would control all

participating Army forces and the Navy commander would control all

participating Navy forces. The Navy would provide close support to the Army

during these operations according to the definition by the joint Chiefs of

Staff:

When, either by direction of higher authority or by agreement between the

commanders concerned, a force is assigned the primary mission of close

support of a designated force, the commander of the supported force will

exercise general direction of the supporting effort within the limits

permitted by accepted tactical practices of the service of the supporting

force. Such direction includes designation of targets or objectives, timing,

duration of the supporting action, and other instructions necessary for

coordination and for efficiency.

Command relationships between the Army and Navy elements

[86]

or components during the operational planning phase would be one of

co-ordination. This particular aspect of the planning directive posed a

basic dilemma in that co-ordination meant agreement at the lowest possible

level as to where the force would deploy and how it would fight. If the

agreement could not be obtained during the planning phase, the planning

directive made provision for the following:

It is the responsibility of commanders at all levels through liaison,

cooperation, coordination, and good judgment to make every effort possible

to solve all command relationship problems in the most expeditious and

workable manner consistent with the problem. Problems which cannot be solved

satisfactorily will not be forwarded to the next higher headquarters until

the commanders concerned have made every effort to reach agreement.

In the event that agreement could not be reached, the division of

component authority meant that each of the component commanders would

proceed up his respective chain of operational control to obtain a solution.

A solution would require co-ordination between the headquarters of the

parallel Army and Navy echelons. For example, in the event that there was a

disagreement between the Navy component commander and the Army component

commander of the Mobile Riverine Force, the Army commander would have to

pass the problem to the commander of the 9th U.S. Division. It is notable

that there was no Navy echelon equivalent to the 9th Infantry Division under

the Navy chain of operational control. The commander of the 9th Infantry

Division would then have to pass the matter to the commander of II Field

Force, who, in turn, would co-ordinate with the parallel Navy commander. (Chart

2)

The command relationships had complicated planning of the location of

initial operations, and prompted Captain Wells to challenge the role of the

2d Brigade as an integral part of the 9th U.S. Division's over-all

operations. This initial disagreement was resolved by Captain Wells'

acceptance of the 9th Division letter of instruction. Determination of the

mission and area of operation of the Mobile River Force in relation to the

9th Infantry Division, however, was a continuous source of friction between

the brigade and flotilla commanders. Generally the commander of River

Assault Flotilla One agreed to the joint Chiefs of Staff provision that the

supported force would direct operations: "Such direction includes

designation of targets or objectives, timing, duration of the supporting

action, and other instructions necessary for the co-ordination and for

efficiency."

[87]

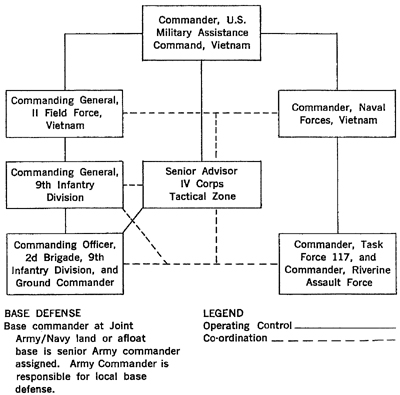

Chart 2 - Mobile

Riverine Force Command Structure

Brigadier General George G. O'Connor, Assistant Commander, 9th U.S.

Infantry Division, was responsible to the division commander for the

division operations in IV Corps. He provided broad guidance and considerable

latitude to the brigade commander in dealing with the command relationships

and operational procedures of the Mobile Riverine Force. Without this degree

of flexibility, it is unlikely that the brigade and flotilla commanders

could have resolved as they did many fundamental issues without recourse to

their respective superiors.

Based on the fundamental issues agreed upon and the campaign plan outline

of where and how the river force was going to fight, planning continued as

the 2d Brigade and its subordinate units began to board the Navy ships of

the Mobile Riverine Force at Dong Tam on 31 May.

[88]

Page created 29 May 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents