- Chapter V:

Plans and Operational

Procedures for the Mobile Riverine

Force

While the Army elements were being moved aboard the

ships of River Assault Flotilla One, the staffs of the flotilla and brigade

completed the planning for initial tactical operations. Lacking the unity of

organization for planning that is present in a joint staff, the brigade and

flotilla commanders informally agreed upon the planning roles of each staff.

Colonel Fulton and Captain Wells decided that Mobile

Riverine Force operations would be planned and conducted on the basis of

intelligence collected from areas in which major enemy forces were most

likely to be met and in which the abilities of a river force could be best

used. Once an enemy force and area had been agreed upon as a target by the

two component commanders, the brigade S-2 and flotilla N-2, working together

closely, would collect intelligence to support further planning. The N-2

would concentrate on the navigability of waterways and threats to the Navy

ships and assault craft. The S-2 would gather intelligence information

necessary to conduct land operations. Both the S-2 and the N-2 would be

highly dependent upon the intelligence disseminated by other U.S. and

Vietnamese headquarters because the Mobile Riverine Force had a large area

of interest and would need to move considerable distances from one location

to another.

Since the S-2 and N-2 could not supply all the information needed by the

riverine force, intelligence was obtained from several agencies. A seven-man

Mobile Intelligence Civil Affairs Team was formed by the brigade to

co-ordinate with these agencies. This team was formed from the brigade S-2

and S-5 sections, the prisoner of war interrogation team, the psychological

operations team, and military police platoons. It moved into the operational

areas of the force to collect intelligence from Vietnamese political

officials and from intelligence officers of military units. Working close

[89]

to the intelligence centers of Vietnamese organizations, the team aided

in the exchange of tactical intelligence as well as in the coordination of a

limited number of civil affairs activities. The Mobile Intelligence Civil

Affairs Team was not usually moved into an area during the planning phase of

an operation for fear of detection by enemy counterintelligence, but was

moved in at the beginning of an operation.

Another means of intelligence collection for the riverine force was the

riverine survey team. Controlled by Task Force 117, the team accompanied the

task force on missions and recorded depth soundings and clearance

measurements, thus providing reliable navigation data for subsequent

operations. Under the direction of the 9th Infantry Division engineer,

Vietnamese Regional and Popular Forces also collected information on bridges

so that the riverine force could be sure of vertical and horizontal bridge

clearance on a waterway.

While they were collecting information, the S-2 and N-2 briefed the

brigade and flotilla commanders and the planners on the area of the

impending operation, and this intelligence along with other information was

incorporated in planning guidance provided by the commanders. It was at the

point of the formulation of planning guidance that - the command

relationships of the Mobile Riverine Force received one of its greatest

tests. By close co-operation, Colonel Fulton and Captain Wells decided upon

the guidance to be issued to their staffs for each operation, and these

agreements in time came to be accepted as an informal set of standing

operating procedures. They were, however, subject to change at any time by

either commander and were not reduced to a written, formally approved

document. Task Force 117 published a standing order that contained the

results of considerable Army and Navy planning but was not jointly approved.

The brigade commander or a higher echelon Army commander usually selected

the enemy target and area of operations. The two commanders then agreed upon

the general task organization, the tentative duration and timing of the

operation, and the location of the mobile riverine base to support the

operation. The planning often included great detail in order to insure that

major issues were resolved early, permitting the two staffs to plan

efficiently.

From the outset, Colonel Fulton and Captain Wells recognized

[90]

the need to plan for future efforts while operations were in progress.

Colonel Turner, who lead been designated riverine adviser, acted as the

planning co-ordinator, with the assistant N-3 (plans) , the assistant S-3

(plans) , the N-2, and the S-2 forming the planning staff. The planning for

operations to take place ten days hence, the planning for the next

operation, three to five days hence, and the execution of the current

operation were accomplished at the same time, with the S-3 and N-3 dealing

with the current operation.

The planning staff, using the commanders' guidance, began by outlining

the scheme of maneuver in the objective area. From there the planners worked

backwards, covering in turn the landing or assault, water movement, and

loading phases. In preparing operations orders they took into consideration

factors peculiar to riverine operations such as tides, water depth, water

obstructions, bridge clearance, distance of the mobile riverine base from

beaches, availability of waterway routes into the area of operations,

suitability of river banks for landing sites, and mooring for barge-mounted

artillery. Operation orders followed the format of the standard,

five-paragraph field order, and were authenticated by the S-3 and the N-3.

The bulk of the information peculiar to riverine operations was in the

annexes, which included intelligence, operations overlay, fire support plan,

naval support plan, signal arrangements, logistics, civil affairs, and

psychological operations information. The intelligence annex supplied

information on terrain, weather, and the enemy situation. Waterway

intelligence was usually provided in an appendix that covered hydrography

and the enemy threat to assault craft. A map of the waterways to be used was

furnished, showing tides, widths and depths of streams, obstacles of various

types, bridges, shoals, mud banks, and other navigation data. The enemy

threat to assault craft was covered in descriptions of recent enemy action

along the waterways, location of enemy bunkers, kinds of enemy weapons

likely to be used in harassing action and ambushes, and water mine and

swimmer danger to the small boats. The operations overlay annex showed

schematically the area of operations, plan of maneuver, and control measures

such as checkpoints. The naval support plan annex contained the naval task

organization and referred to the operations order for information concerning

the situation, mission, and concept of operations. It assigned specific

support tasks to subordinate naval elements together with the necessary co-ordinating

instructions. An appendix to the naval support plan provided waterway data.

[91]

Battalion orders for operations in a riverine area followed the format

used in the brigade orders and were authenticated by the battalion S-3. The

supporting river assault squadron water movement plan was prepared by the

river assault squadron operations officer in co-ordination with the

battalion S-3. It was, in effect, the river assault squadron operations

order. This plan did not become a formal part of the battalion operations

order but was attached to it. The water movement plan contained the task

organization, mission, schedule of events, boat utilization plan, command

and communications instruction, and co-ordinating instructions. The schedule

of events paragraph listed events critical to the operation and the time

they were to take place, for example, where and when each unit was to load,

and its scheduled time of arrival at critical water checkpoints. The boat

utilization paragraph included numerical designations of boats and the

companies to embark on these boats. The co-ordinating instructions paragraph

included information on submission of reports, radio silence, recognition

lights, reconnaissance by fire, and the use of protective masks.

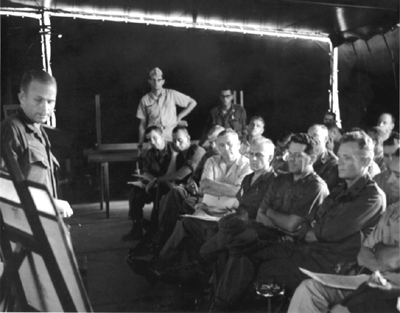

Once approved, both the brigade and battalion operations orders became

the authority for fulfilling the intent of the scheme of maneuver and for

providing combat and combat service support. Prior to each operation, a

briefing was conducted on the flagship of the Mobile Riverine Force; it

included presentation of the plan of each battalion and squadron, as well as

the latest S-2 and N-2 intelligence. Briefings seldom required decisions by

the flotilla or brigade commander because problems had been resolved between

the Army and Navy elements at each subordinate echelon and between echelons

during planning. Beginning in June of 1967, plans and orders were in far

greater detail than the Army brigade and battalion commanders believed was

needed or even optimum for routine land warfare. The detailed nature of the

plan, however, included agreements at the Mobile Riverine Force command

level; the Navy commander desired to define clearly the tasks to be

performed by each service. For the Navy commanders and staffs, the detailed

plan was less objectionable, being similar to the planning associated with

amphibious, ship-to-shore operations. After June of 1967 as time passed both

Army and Navy commanders realized that matters such as the loading of a

battalion from a barracks ship onto the assault craft of a river assault

squadron and the configuration of a battalion river assault squadron convoy

were standing operating procedure. The Mobile Riverine' Force was

nevertheless to rely heavily on detailed operations orders

[92]

MOBILE RIVERINE FORCE BRIEFING ABOARD USS BENEWAH

rather than a formal, written standing operating procedure for many

months of its operations.

The initial operations of the Mobile Riverine Force during the period 1

June to 26 July 1967 were designated Operation CORONADO I. From 3 June

through 10 June operations were conducted in the vicinity of Dong Tam, and

were designed to make the land base more secure and to test the operational

procedures of the force. A tactical operations center manned jointly by the

Army and Navy provided a focal point for communications and for monitoring

operations and could fulfill the needs of the riverine brigade and flotilla

commanders separately.

At the levels of maneuver battalion and river assault squadron, the

staffs operated independently but maintained close, harmonious

relationships. The maneuver battalion staff Outranked and outnumbered the

river assault squadron staff. Because of a limited staff, the naval river

assault squadron was unable to perform staff functions which corresponded to

those of the infantry battalion it

[93]

supported. This limitation contributed to the centralization of planning

at the flotilla level. The two boat divisions organic to the river assault

squadrons also were limited in their planning. The rifle company commanders

transacted their business with naval enlisted men, who did not have .the

authority to make decisions. Time could be lost at the company and boat

division level in situations requiring quick decision.

Operations consisted of co-ordinated airmobile, ground, and waterborne

attacks, supported by air and naval forces. The ground and naval combat

elements traveled to the area of operations by river assault squadron craft,

helicopter; or a combination of these means. While the boats would serve as

a block and could transport troops in the early stages of an operation, once

the troops had engaged the enemy more speed was necessary and air

transportation of forces was generally more satisfactory.

The basic offensive maneuvers used by the Mobile Riverine Force were to

drive the enemy against a blocking force, with the open flanks covered by

Army helicopter gunships, or to encircle him. These maneuvers were based on

the estimate that the enemy would choose to fight only when he thought he

could inflict heavy casualties or when he was surprised and forced to fight.

If he chose not to fight, he might attempt to take advantage of the

concealment afforded by the numerous tree-lined waterways by dispersing into

small groups and leaving the area of operations under the protection of

small delaying and harassing fire teams. It was necessary for U.S. forces to

establish blocking positions quickly and to be able to deploy troops

rapidly. Several maneuver battalions were needed, but the Mobile Riverine

Force had usually only two battalions, a situation that provided further

incentive for co-ordinating operations with Vietnamese or other U.S. units.

Control of the riverine forces was aided by reliable and versatile

parallel Army and Navy communications systems, by operations conducted over

flat terrain by units within mutually supporting distances, and by command

helicopters used at the brigade and battalion levels. Troop movements were

controlled and co-ordinated from the flagship. The focal point for control

was the joint tactical operations center, the Army element of which was

under the supervision of the brigade executive officer. Staff representation

came from the S-3, S-2, N-3, air liaison, Army aviation, and artillery fire

support sections, and the center was operational at all times.

During operations the brigade employed a forward command group, usually

located at the fire support base, and composed of the

[94]

TROOPS PREPARE TO EMBARK FROM AMMI BARGES

brigade commander, the brigade S-3, the brigade assistant fire support

co-ordinator, and the air liaison officer. The brigade command group was

generally aloft in- a command helicopter in daylight hours. The battalion

command post was fragmented into a forward and a rear tactical operations

center. The forward post was located in a command boat that accompanied the

troops during their waterborne movement and normally consisted of the

battalion commander, S-3, assistant S-3, artillery liaison officer, an

operations sergeant, an intelligence sergeant, and two radio telephone

operators. The river assault squadron commander and his operations officer

were aboard the same command boat. The rear command post was located aboard

ship at the mobile riverine base and usually consisted of the battalion

executive officer, S-1, S-2, S-3, S-4, an operations sergeant, and two radio

telephone operators. When a command and control helicopter, usually an

observation type, was available, the battalion commander and his artillery

liaison officer controlled the operation from the air.

After the briefing that took place before each operation, battalion

commanders and supporting river assault squadron com-

[95]

MONITORS AND ASSAULT PATROL BOATS HEAD IN TO SHORE

manders issued final instructions to their staffs and subordinate

commanders. These confirmed or modified previously issued orders. Each rifle

company was allocated three armored troop carriers, and arrangements were

made to load bulk cargo and ammunition prior to troop embarkation. At the

designated loading time for a particular company, three armored troop

carriers were tied alongside the Ammi barges moored to the ship and three

platoons of a company embarked simultaneously. In most instances, the

loading of a complete company was restricted to twenty minutes. The Navy

stationed expert swimmers on the barges prepared to rescue men who might

fall overboard. Once a company was loaded, the ATC's proceeded to a

rendezvous where they waited for the remainder of the battalion to load.

Upon completion of the battalion loading, the ATC's moved at a specified

time across a starting point and thence to the area of operation. Army

elements observed radio silence; the naval radio was used only for essential

traffic control.

The boats moved across the starting point in column formation, the

leading assault support boats providing minesweeping and fire support. Each

minesweeper was equipped with a drag hook that

[96]

ASSAULT CRAFT GOING IN TO LAND TROOPS

was tethered with a steel cable to a high-speed winch. Two of the leading

minesweepers preceding on the flanks of the column dragged these hooks along

the bottom of the waterway in an effort to cut electrical wires rigged to

underwater mines. The river assault squadron commander traveled aboard the

leading command and control boat. The battalion commander was either in the

control boat or in a helicopter aloft. Each supporting river division was

[97]

divided into three sections, each section consisting of a monitor and

three ATC's supporting the one rifle company. These sections were in such

order in the column as to maintain infantry company integrity and to place

units on the beach in the order specified by the battalion commander. While

underway, the river assault squadron commander exercised command and control

of the boats. The rifle company commanders monitored the Navy command and

control and the battalion command net in order to stay abreast of developing

situations. Radar was the principal navigational aid during the hours of

darkness.

Water checkpoints were designated along the routes as a means of control,

and as march units passed these a report was made to the- joint tactical

operations center. Whether on large rivers or small streams, river assault

units were faced with the threat of hostile attack. However, when the boats

left the large rivers for the smaller waterways the danger from recoilless

rifles, rocket fire, and mines increased. The waterways negotiated by the

boats varied from a width of 100 meters where the smaller waterways joined

the river to widths of 15 to 25 meters. The formation that the boats assumed

was similar to that used on the main river except that the leading

minesweepers moved to positions nearer the column. While the column

proceeded along the small waterways, suspected areas of ambush (if in an

area cleared by the Vietnamese government) were often reconnoitered by fire

from the small boats and by artillery.

When the lead boats of the formation were approximately 500 meters from

the beach landing sites, artillery beach preparations were lifted or

shifted. The leading minesweepers and monitors then moved into position to

fire on the beaches on both sides of the waterway. This fire continued until

masked by the beaching ATC. If no preparatory fire was employed, the boats

landed at assigned beaches in sections of three, thus maintaining rifle

company integrity. Boats within a section were about 5 to 10 meters apart,

and a distance of 150 to 300 meters (depending on the beach landing sites

selected for each company) separated each boat section or assault rifle

company. After the units had disembarked, the boats remained at the beaching

site until released by the battalion commander. Upon release, the river

assault squadron craft either moved to provide fire support to the infantry

platoons or moved to interdiction stations and rendezvous points. Subsequent

missions for the boats included independent interdiction, resupply, and

extraction of troops.

[98]

TROOPS GO ASHORE FROM ARMORED TROOP CARRIER

After landing the troops secured initial platoon and company

objectives and moved forward in whatever formation the terrain and mission

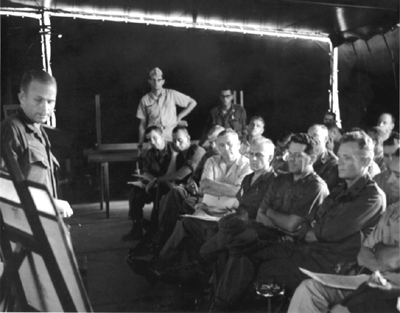

required. (Diagram 6) When contact with the enemy was made, commanders

immediately acted to cut off possible enemy escape routes. The most

frequently used tactic was to move units to blocking positions to the flanks

and rear of the enemy and direct extensive artillery fire, helicopter

gunship fire, and air strikes into the enemy positions. After this softening

up process, troops swept the area.

The Mobile Riverine Force had little trouble finding suitable helicopter

landing and pickup zones. Pickup zones used to mount airmobile operations

were normally located in the vicinity of the fire support base or on terrain

adjacent to the waterways. When there were not enough aircraft to move an

entire company at one time, platoons were shuttled into the area of

operations. The brigade standing operating procedure called for helicopter

gunships to escort each serial, and for an airborne forward air controller

to operate along the route of aerial movement.

[99]

Diagram 6. Typical company landing formation.

During each day plans were made to arrive at a night defensive position

before dark unless troops were engaged with or pursuing the enemy. After

resupply, the night defensive position was organized against possible enemy

attack.

The fourth rifle company of each battalion was usually employed at the

fire support base under operational control of the base commander; for

mobile riverine base security it was under direct control of the Mobile

Riverine Base commander.

When the river-assault craft remained overnight on the small waterways in

the operational area, the brigade and battalion commanders planned for

security of the boats, which were usually kept near infantry elements

ashore. The boat fire was integrated with the fire of other units.

Withdrawal of riverine forces from the area of operations was

accomplished chiefly by boat. When units operated far inland from navigable

waterways, however, they were extracted by helicopter and taken to a landing

zone near a navigable waterway. They were then transported by boat to the

Mobile Riverine Base or to another area of operations. Sites designated for

picking up troops were often on streams lined with dense banana groves,

coconut groves, or nipa palm that made it difficult for both the ground unit

[100]

commander and the river assault squadron commander to spot. Ground and

water movement to the site was therefore controlled and co-ordinated from

the battalion commander's helicopter. The commander marked specific beach

and unit locations with colored smoke and directed the Army and Navy

elements to them by radio.

The same boat that was used to put an Army element ashore was also used

to bring it out. Each boat carried an identifying number and flew a

distinctive colored pennant from the mast that could be recognized by troops

who were behind dikes and vegetation. Each boat also carried three running

lights tiered near the top of the mast. Through the use of varying color

combinations in the top, center, and bottom running lights, the boat

designated for each boarding element could be readily identified.

Tides, draft, and maneuver room were primary considerations when boats

were scheduled to rendezvous with Army forces for pickup because tides not

only affected the water depth in canals, but caused significant changes in

current velocity and direction. Traveling a distance of thirty kilometers

upstream could take up to six hours against an ebbing tide, whereas the same

route might be covered in four and a half hours on an incoming tide.

The threat of ambush during troop removal was considered as great as

during movement to landings. When possible, an alternate to the route used

for entering an area was selected for picking up troops. Beaching of the

boats was usually accomplished with little difficulty because the

infantrymen on shore had reconnoitered the banks for obstacles. Army

security elements were placed 100 to 150 meters inland from the extraction

site. After the troops were aboard, the boats resumed tactical formation and

moved along the canal or stream and into the major waterway where the Mobile

Riverine Base was anchored.

During offensive operations, the commander of the Army element of the

Mobile Riverine Force in his position as base commander for all joint Army

and Navy bases was also responsible for the defense of the Mobile Riverine

Base. The Navy provided its appropriate share of forces, which included

those for gunfire support and protection against waterborne threats. Defense

of the base also involved arrangements for curfew and other restrictions for

water craft with appropriate Vietnamese civilian and military officials in

the immediate vicinity.

River assault divisions were assigned the responsibility for waterborne

defense on a rotating basis. They conducted patrols to control river

traffic, enforce curfews, and deter attack by water;

[101]

swept the vicinity of the Mobile Riverine Base for water mines; sent

demolition teams to inspect underwater anchor chains, hulls of ships, and

pontons for limpet mines; and dropped random explosive charges in the

anchorage area to deter enemy swimmers.

One rifle company under the base commander was responsible for shore

defense of the Mobile Riverine Base. Normally the company employed one

platoon on each bank of the river and held the remainder of the company in

reserve. Since anchorage space was 2,000 to 2,500 meters in length, it was

impossible to conduct a closely knit defense with the relatively small

number of troops committed. Platoon ambush sites were established on the

banks opposite the flotilla flagship and during daylight hours security

patrols were dispatched to provide early warning of enemy attack. The

security troops were reinforced as needed by elements of the company

defending the fire support base. Artillery and 4.2-inch and 81-mm. mortar

fire as well as fire from the boats was planned in support of the defense of

the base. The flat trajectory of naval weapons fire required careful

planning for both shore and waterborne defense.

The planning and operational procedures initially used by the Mobile

Riverine Force were refined as the staff and the force gained experience.

The first significant test of these procedures came during operations in

Long An Province in the III Corps Tactical Zone.

[102]

Page created 29 May 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents