CHAPTER II

Unit Management and Personnel Actions

In a counterinsurgency environment commanders rarely have all the resources required. One can always use more men to secure and pacify an area, or air assets to carry on operations, or more supplies, and on and on. Nevertheless, assets are of necessity limited and therefore commanders must often choose between conflicting goals and most of the time must settle for sub optimization in their courses of action. We realized early that it was impossible to optimize the thousands of factors that enter into running an infantry division. To stay on top of the game, decisions had to be satisfactory and timely rather than optimal. We settled for satisfying a large number of subsystems: awards and decorations, leaves, repair parts, sensor devices, POL (petroleum, oils, and lubricants) storage, vehicular transportation, guard, post exchange support, artillery, and hundreds of others. However, two areas were identified that had such an impact on the combat effectiveness of the division that we sought to optimize rather than satisfy these areas to insure that the total system was maximized. These areas were: (1) the number of infantrymen in the field on a daily basis; and (2) the number of aviation assets available to support the infantrymen in the field. The first part of our double barreled effort was to provide the largest number of healthy, motivated, well-equipped, properly supported infantry soldiers to the field commanders on a daily basis. In this chapter are described unit management and personnel actions; in the next chapter maximizing army aviation assets and support facilities will be discussed. These will tell the story of how we optimized our assets.

The 9th Division in the late spring of 1968 found itself with its fighting edge somewhat dulled as the consequences of an extensive area of operations, static missions, its table of organization, the tempo of operations, a split Division Headquarters and the losses sustained in Tet and the Mini-Tet of May 1968. The factors which reduced the number of infantrymen in the field were the result of an organizational situation and the severe combat of Tet and were not controllable at the time by the able commanders who had preceded us in the 9th Infantry Division. However, as

[15]

mentioned earlier in our strategic analysis, the post-Tet situation was different. We were in a position to take advantage of restructuring of the division along the lines recommended in the Army Combat Operations Vietnam study as well as completing the final phase of relocation to the delta envisioned by General Westmoreland several years earlier. This move enabled us to reduce our static missions and to operate much more efficiently on interior lines with a smaller area of responsibility. In all, there were six major actions involving unit management and personnel that materially increased the number of infantrymen in the rice paddies on a daily basis: changing the mix between straight-leg and mechanized infantry battalions; converting from three to four company rifle battalions; obtaining a tenth rifle battalion; getting a handle on strength accountability; attacking our foot disease problems; and unloading static missions. All of these efforts jelled in the winter and spring of 1968-1969, greatly increasing the combat power and flexibility of the division. With a greater number of well-equipped and supported infantrymen in the paddy, we were able to forge a much longer and keener cutting edge to our combat sword.

The 9th Division was initially organized with seven rifle (foot) battalions and two mechanized infantry battalions. This was probably the correct mix for its original mission and area around Saigon. As the division moved south into the delta and as the enemy was broken up and began to evade, the need for two mechanized battalions became less pressing. In fact, it became more and more difficult to employ two such units usefully. The muddy terrain affected their mechanized vehicles too much. This was particularly true after the enemy gave up trying to ambush on the highways and mechanized highway patrols were consequently no longer needed. The last time that the mechanized battalions fully earned their keep was during the Mini-Tet attack on Saigon when both battalions made forced marches into the southern Saigon suburbs and really hurt the enemy due to their firepower and shock action. After that, the mechanized units were almost more of a hindrance than a help. These battalions were also handicapped by only having three rifle companies, which reduced their ability to control large areas and their staying power. In fact, we finally had to, keep them partially unhorsed in order to force them into learning to conduct effective offensive small-unit foot operations. As it became obvious that we needed more foot infantry, we were able to swap one of our

[16]

THE COMBAT EDGE

mechanized battalions for a foot battalion of another division and settled down with nine foot battalions and one mechanized. (We had in the meantime gained a tenth battalion from the Continental U.S. base.) In late 1968 and 1969, ten foot battalions would have been preferable in the delta, but it was too late in the Vietnamese operation for force structure changes, however desirable.

[17]

The Four-Rifle Company Conversion

The 9th Infantry Division was brought to Vietnam under a personnel ceiling that made it necessary to hold all the rifle battalions to three-rifle companies. This triangular organization, while quite workable in Europe and Korea, with their essentially linear wars, was very awkward in Vietnam. The need to cover terrain and the desirability for constant pressure on the enemy were hard to accomplish with a triangular organization. Many of the difficulties were rather hard to quantify but the Army Combat Operations Vietnam evaluation conducted in 1966-67 pinned the problem down and clearly demonstrated the need for a square (four-rifle company) battalion.

Having been exposed to the full effect of triangular battalions for some months in Vietnam, we will limit ourselves to saying that it is a miserable organization for semi-guerrilla operations. (As a matter of interest, one difficulty that most South Vietnamese Army divisions must overcome is that their battalions are triangular. Only the "elite" units-airborne, ranger, Marines, and parts of the 1st South Vietnamese Army Divisions-are square.) Fortunately, the desirability (or necessity) of "squaring" the 9th had been recognized and the program had been set into motion for the fall of 1968 and spring of 1969. Thus, the 9th Division during this period gained about 33 percent in rifle strength and somewhat more than that in flexibility and staying power.

In early 1968 the Cavalry Squadron of the 9th Division (3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry) was moved to northern I Corps (Quang Tri area) to give more armored weight to that area. While the cavalry was quite useful in the division's original area east of Saigon, its usefulness south of Saigon was limited due to the rice paddy terrain. However, its transfer to I Corps resulted in a net loss of three company size (troop) maneuver units. In the spring of 1968, a new infantry battalion (originally earmarked for the Americal Division, we believe) was arriving in-theater. Due to the tremendous geographical spread of the 9th Division and possibly the loss of its Cavalry Squadron, this battalion (6th Battalion, 31st Infantry) was assigned to the 9th Division. At the time, the increase of one square battalion meant an 11 percent increase in rifle battalions and a 14 percent increase in rifle companies for the division. More importantly, when the division settled down in the delta, it allowed

[18]

each brigade to have three battalions (3 X 3 = 9) with one left over to secure the rather exposed division base at Dong Tam.

Brigade organization is an interesting subject in itself. In our opinion, a two-battalion brigade in Vietnam was of marginal usefulness. A three-battalion brigade handled reasonably well (from the brigade commander's point of view). From occasional experience, a four-battalion brigade seemed the most effective arrangement.

As an important afterthought, when the 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry was detached, its Air Cavalry troop remained with the division. This was fortunate, as a division in Vietnam without an air cavalry troop was blind. In addition, the absence of the Cavalry Squadron, perforce, placed the air cavalry troop under division control, which was a very responsive arrangement.

In March of 1968, it was not readily apparent that the rifle company strength of the 9th Division was critically low, although it in fact was. The overall strength of the division and even the battalions was quite high, but on critical examination, it could be seen that the shortages were concentrated in the rifle companies. The division had seen hard fighting during the Tet battles as well as in the post-Tet counteroffensive in Dinh Tuong Province. The average loss per company may have been higher than in other

PADDY STRENGTH

[19]

divisions as the 9th was one of the few units in the theater with three-rifle company battalions. In hard fighting, the exposure rate of each company to losses tended to be higher than in a four-rifle company battalion. Also, the number of replacements available per division dropped due to the overall losses throughout Vietnam so that losses outweighed gains by an appreciable amount. As a result of all of these factors, many companies ended up with a "paddy strength" of 65 or 70. ("Paddy strength" is the term we used in the wet delta for the number of riflemen present for duty on the battlefield.) A company this size did not handle well in combat and could not stand up well to constant pressure.

Although the men and their commanders did their best without grumbling, it was readily apparent that the strength situation of the division at the combat level would have to be improved markedly if the combat effectiveness of the units was to be increased.

Once we found that our offensive strike capability had been severely blunted by lack of combat infantrymen in the field, we had to establish procedures to increase the paddy strengths of the tactical units. We did not have to look far for improvement because it became obvious that the division headquarters was too fat. First, we eliminated all augmented strengths and temporary duty personnel, except for the Division Headquarters and Headquarters Company and the Division Administration Company. Then we hacked away at these two headquarters units. We pruned the temporary duty personnel by more than half until they totaled about 300 personnel, or less than two percent of the total division strength. Since US Army Vietnam tried to keep all divisions at approximately 102 percent strength, this enabled all of our divisional units to remain at their full Table of Organization and Equipment authorizations-an important factor.

In attacking the problem, we started using the normal personnel reports based on the Morning Report. Unfortunately, this system has a built-in time lag of several days which is aggravated during combat conditions and, while going into gains and losses in detail, does not show exactly how many men are actually in combat. We therefore devised a rather simple daily report suitable for radio reporting, called the Paddy Strength Report, which reflected in real time, on a daily basis, exactly how many men were in the paddy. Initially, this information was a rather bitter brew to take, as it showed that our fighting units were much lower strength-wise than our more normal reports suggested.

There were four major problem areas. First, unit losses due to rotation and battle casualties were not being replaced in a responsive

[20]

fashion. Second, there were diversions of infantry soldiers from line units to brigade and battalion headquarters. Third, there were diversions to run fire support bases where the necessary security and morale activities such as guard, clubs, and post exchange, soaked up enlisted men in alarming amounts. Fourth, there were unexpectedly large numbers of enlisted men attending sick call or with permanent physical profiles which precluded their use in field combat.

To get a handle on these problem areas, the Paddy Strength Report, requiring all maneuver units including brigade headquarters to report their combat strengths on a daily basis, was revised. A very simple format was evolved utilizing morning report data to the maximum extent possible and a set of guidelines was established. The following table and discussion succinctly summarizes the paddy strength reporting procedures and goals:

| Problem | Monitorship Responsibility | Guideline Maximum Leeway | Resulting Rifle Company Strength | Items Reported (Nomenclature) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

164 | Authorized Strength | ||

| Replacements not

properly assigned. |

G-1, Division Headquarters | 4% or 7 enlisted men | 157 | Assigned Strength |

| Diversions to Brigade

and Battalion Headquarters, leave, and Temporary Duty. |

Brigade Headquarters | 10% or 16 enlisted men | 141 | Present for Duty Strength |

| Diversions to cover unit overheads, sick call, physical profiles, guard, etc. | Battalion Headquarters | 15% or 21 enlisted men | 120 | Paddy Strength |

The Division G-1 was responsible for insuring that all maneuver battalions had assigned at least 96 percent of their authorized strength. The Brigade Commander was then responsible for insuring that brigade and battalion headquarters did not siphon off too many assigned personnel. His guideline was that only 10 percent of assigned personnel could be absent from duty. Thus, the present-for-duty strength per rifle company should have been approximately 141 enlisted men.

The Battalion Commander was responsible for insuring that 85 percent of the present-for-duty personnel were available for combat

[21]

THE DELTA ENVIRONMENT-FINDING A CACHE

operations. This meant that a maximum of 21 enlisted men could be diverted to unit overhead. The battalion and company commanders had to keep a tight rein on sick call and physical profiles. Thus the paddy strength of the rifle companies should be at or above 120 enlisted men. This was our key strength figure-one which every company commander knew well.

Actually, the first Paddy Strength Reports were real shockers. They showed, as stated earlier, not only the expected diversions to headquarters units but, more importantly, that there were a large number of combat infantrymen hitting sick call almost daily or walking around with permanent profiles which barred them from field duty. Some units had as many as 50 percent of their unit strength non-available for combat duty because of foot problems alone. Although it was. recognized that foot disease had been a severe medical problem in the wet delta, it had not dawned on anyone that the problem was as widespread or as important as the Paddy Strength Reports indicated. Two actions were immediately initiated. The first was to reassign those combat infantrymen with long-term or permanent profiles. In this respect, U.S. Army Vietnam

[22]

was extremely helpful because they accepted the transfer of 11 Bravos (riflemen) to other units in Vietnam such as depots, where the soldiers would not be required to work constantly in water and where they could perform their jobs adequately in sandals if necessary. The second effort was the initiation of "Operation Safe Step" for the purpose of controlling and minimizing foot problems. This medical research effort proved to be the most important single factor in increasing the paddy strength of the 9th Division.

By holding our feet to the fire, literally and figuratively, our strength situation began to correct itself. After some months the rifle companies were putting 120 men in the paddy routinely and the problem became self-solving and needed only occasional reemphasis.

The Paddy Strength Report indicated that there was a significant loss of manpower due to sickness that was not being reported through medical channels. Upon investigation, it was found that this loss was due to skin disease, largely of the feet and lower leg, and that not only was the medical reporting system inadequate to measure the losses, but medical personnel lacked the specialized training to make accurate diagnosis or to develop effective preventive measures.

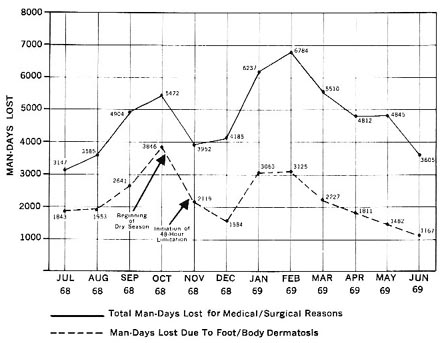

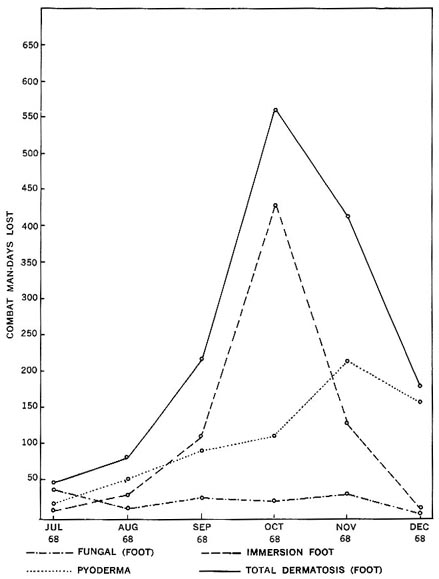

As noted previously, the 9th Division Area of Operations in the delta of Vietnam consisted primarily of inundated terrain including rice paddies and swamp land cut by an intricate complex of canals and streams. As a consequence, skin disease was consistently the major single medical cause of combat noneffectiveness in the 9th Infantry Division. During Fiscal Year 1969, skin diseases of the foot and the boot area accounted for an average of 47 percent of the total combat man-days lost, or an average of 2,238 man-days lost per month. (Table 2 and Chart 1) These statistics, although alarming, follow the norm to be expected, because in wars disease usually incapacitates far more soldiers than wounds. Historically, in the tropics, skin disease has been a leading cause of morbidity and lost man-days. During World War II, about 16 percent of the soldiers evacuated from the South Pacific were sent back to the United States for diseases of the skin. In the tropical Southeast Asia area in the British Malayan campaign, skin diseases were the largest single cause of hospital admissions. During their nine years in Indochina (1945-1954) , the total French force of 1,609,987 soldiers suffered 689,017 hospital admissions for skin diseases. In Vietnam overall, the four leading causes of noneffectiveness from disease in

[23]

TABLE 2-COMBAT MAN-DAYS LOST, 9TH INFANTRY DIVISION MANEUVER BATTALIONS, 1968-1969

| Date | Total Medical/Surgical | Dermatological Foot/Body | Dermatological: Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | |||

| JULY | 3147 | 1843 | 59% |

| AUGUST | 3585 | 1953 | 54% |

| SEPTEMBER | 4904 | 2641 | 54% |

| OCTOBER | 5472 | 3846 | 70% |

| NOVEMBER | 3952 | 2119 | 54% |

| DECEMBER | 4185 | 1584 | 38% |

| 1969 | |||

| JANUARY | 6237 | 3063 | 49% |

| FEBRUARY | 6784 | 3125 | 46% |

| MARCH | 5510 | 2227 | 40% |

| APRIL | 4812 | 1811 | 38% |

| MAY | 4845 | 1482 | 31% |

| JUNE | 3605 | 1167 | 32% |

the US Army were acute respiratory infections, diarrhea, skin diseases, and malaria.

Once the crippling loss of combat strength due to skin diseases was fully appreciated, this factor received strong command interest. We initiated multiple approaches to save time-studying this complex problem on several fronts concurrently. We needed a quick fix. Medical personnel under Colonel Archibald W. McFadden investigated three areas: the nature and causes of these diseases, the actual manpower lost, and simple yet effective control measures. From the outset two facts were obvious. First, only infantry soldiers developed severe incapacitating diseases of the foot and lower leg area and second, it was almost impossible to avoid when operating in the wet terrain of the Mekong Delta.

Our three pronged attack on skin disease was called "Operation Safe Step." It included a controlled series of experimental testing of different models of foot gear, skin protective ointments, and timed exposure to paddy water by a group of enlisted volunteers within the perimeter of the Dong. Tam Base. The latter was a most interesting aspect of the investigations, and probably unique in an infantry division in an active combat zone. During the period August 1968 through June 1969, approximately 100 infantrymen were detailed for varying periods to the Division Surgeon for this project in three separate increments. These volunteers included men fresh in the country, experienced paddy soldiers with up to 10 months in the field, combat veterans without skin problems, and

[24]

CHART 1-COMBAT MAN-DAYS LOST, MANEUVER BATTALIONS, 9TH INFANTRY DIVISION, 1968-1969

men newly recovered from severe skin disease. This experiment in practical research was suggested by Colonel William A. Akers, Chief of Dermatology Research Division, Letterman Army Institute of Research, and Professor David Taplin, Dermatology Department, University of Miami, and was conducted by the Division Surgeon, assisted by personnel from the 9th Medical Battalion. This was extremely interesting research, and personnel who are knowledgeable in medical research techniques could well afford to inquire into this approach in more detail. Overall, it was a multi-disciplined analysis and, and because of Professor Taplin's pragmatic approach, we rapidly delved into what the diseases actually were and determined more effective treatments.

Through "Operation Safe Step" we initially tried to discover the single "magic" solution to this serious skin disease problem, which would solve it without interfering with the standard infantry tactics of five or more days of unrelenting, aggressive pressure on the Viet Cong. Imaginative and ingenious variations of the standard tropical boot, which were suggested by the Division Surgeon and developed by the US Army Laboratory, Natick, were extensively tested. Un-

[25]

fortunately, these experimental boots were not too helpful. The testing proved that no easy answer existed and that we must experiment with modifications of standard infantry tactics and troop management.

The experiments were conducted in rice paddies, banana groves, and swamp areas within Dong Tam Base, which exactly duplicated the inundated terrain of the delta without the hazards of combat. These tests continued throughout this period and yielded valuable results and confirmation of suggestions from the field. Utilizing volunteer soldiers, six experimental boot models, four experimental boot socks and three protective ointments and lotions were evaluated. The average skin tolerance to water was tested and several anti-leech and mosquito repellents were tested. Experiments were conducted by volunteers barefooted, wearing standard boots and socks, and wearing different boots and socks under controlled timed conditions. Details of the testing of footwear are indicated in the report below:

HEADQUARTERS 9th INFANTRY DIVISION

OFFICE OF THE DIVISION SURGEON

APO SAN FRANCISCO 96370

TESTING OF FOOTWEAR FOR THE MEKONG DELTA

OPERATION SAFE STEP: PHASE II, 1969

In an effort to decrease the skin anti foot problems which result from extensive tactical operations in the wet terrain of the Mekong Delta, several new items of footwear were assigned to the Office of the Division Surgeon for testing under simulated combat conditions. Experimental testing of a new Zipper Boot, a 100 % Nylon sock (stretch) and a Nylon mesh sock, and a Comfort Slipper has been carried out since early February. The testing and evaluation of these items has recently been concluded and the results are discussed below.

In the first of four separate experiments, the new Zipper Boot was compared to the standard issue Tropical Boot when worn with regular issue O.D. wool socks. No clinical difference in the progression or severity of foot disease was detected between the two boots. However, the volunteers felt that the Zipper Boot drained and dried faster than the Tropical Boot. The thin synthetic material of the Zipper Boot tended to "give" in tension areas, especially around the seams.

The second test compared the 100 % Nylon stretch sock with the regular issue wool sock, worn with the standard issue Tropical Boot. The 100 % Nylon sock was found to be definitely superior in retarding foot disease due to its fast drying qualities. The men also felt the Nylon sock to be much more comfortable because it didn't hold water or "bunch up" under the foot. They suggested that if the Nylon sock were thicker, it might offer protection from abrasion inside the boot, although this problem was not significant.

[26]

The third test compared the Zipper Boot to the Tropical Boot when worn with 100% Nylon stretch socks. The Zipper Boot was found to be on balance superior to the Tropical Boot in this test. Presumably, the increased ventilation of the Zipper Boot became more effective in combination with the fast-drying qualities of the Nylon sock. It was again noted that the material of the Zipper Boot frayed easily in stress areas of the Boot. A few men complained that the Nylon sock permitted fine sand to enter between the sock and foot, causing an abrasive effect.

The fourth experiment compared the 100% Nylon stretch sock to the Nylon mesh sock, both worn with the Tropical Boot. The mesh sock was found to be inferior to the stretch sock in preventing foot problems. The mesh sock permitted sand and grit to enter easily, and the abrasive effect of the sand and grit was probably responsible for the early breakdown of the skin. The mesh sock also tore in several cases.

Comfort Slippers Types I and II (lace type and velcro fastener type) have been given initial field tests. The lace type Comfort Slipper proved to stay on the foot better when actually running through paddy type terrain. The fastener type was easier to take on and off, and thus more suitable for base camp conditions. When the fastener type Slipper was laced through the auxiliary eyelets, it too remained on the foot during the paddy run.

Long range field studies of the Zipper Boot, the 100% Nylon stretch sock, the Nylon mesh sock, and the Comfort Slipper are now in progress among the maneuver battalions of the Division. These studies should be concluded within one month.

A. W. MC FADDEN, MD

COL, MC

C, DC&CHCS

A summary of findings of "Operation Safe Step" follows:

(1) Normal healthy skin can tolerate about 48 hours of continuous

exposure to paddy water and mud before developing Immersion

Foot Syndrome.

(2) Fungal infection of the severe inflammatory type due to

Trichophyton Mentagrophytes did not develop until after about three

months of paddy duty.

(3) Nylon boot socks were markedly better than the issue wool

boot socks in reducing skin disease, quick drying, comfort and

troop acceptance.

(4) Soft, tennis shoe-like NOMEX comfort shoes were valuable in

replacing combat boots in base camp for the same reasons as noted

above.

(5) No experimental boot tested was completely suitable

for use in the Mekong Delta terrain. Suggestions for improvement in

the standard boot included the adoption of the "Panama Sole"

[27]

design, reduction of the amount of leather, replacement of

canvas with strong NOMEX fabric and zippers instead of laces.

(6) Miscellaneous experiments resulted in the following conclusions

or recommendations:

(a) Silicone protective ointments were useless due to discomfort

and troop rejection.

(b) A protective lotion supplied by Colonel William A.

TAKING TEN

[28]

IMMERSION FOOT?

[29]

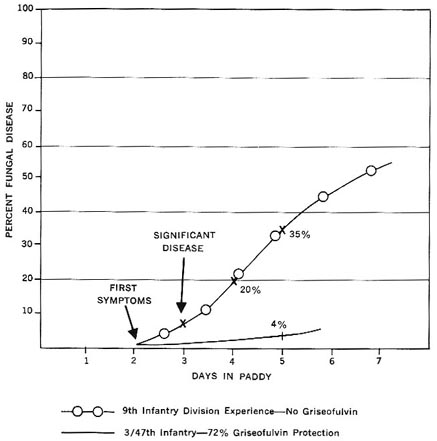

CHART 2-FUNGAL DISEASE (FOOT AND BOOT AREA)

Akers, MC, showed promise in delaying the onset of Immersion

Foot Syndrome.

(c) The anti-leech lotion was not acceptable to the troops and

therefore not effective.

Three important diseases were identified through investigations in the field and practical research in "Operation Safe Step." These diseases all affected the foot and boot area; yet, each required a specific treatment:

(1) Fungal Infection. In the tropics fungal infections on the body usually begin as small reddish scales around the ankles, on the top of the foot, on the buttock and on the groin. Itching is mild at first but can become unusually severe. Tiny vesicles appear and when the patient scratches off the top of the vesicles bacteria invade, causing secondary infections. Although the patient with extensive or very inflamed fungal infection may be quite miserable

[30]

and incapacitated for several weeks, his general health is unharmed and he will fully recover. Fungal infection can be both treated and prevented, to a substantial degree, by Griseofulvin, an anti-fungal antibiotic. The graph in chart 2 indicates the disabling effects of fungal infections.

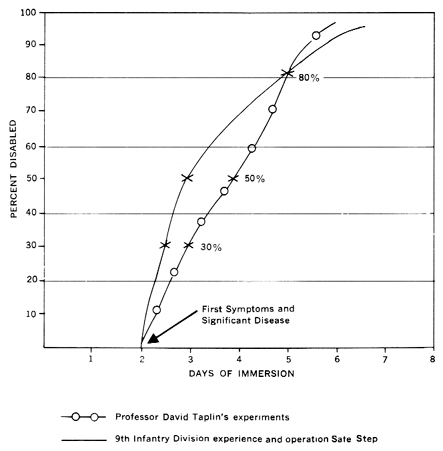

(2) Immersion Foot. Immersion foot in its classic form is unique to the 9th Division in the delta. It almost inevitably develops in approximately 95 percent of all personnel exposed. Its late results are similar to cold weather trench foot of World War II with damaged circulation and intolerance to cold weather. It is caused by prolonged exposure to rice paddy, water, and mud in the tropical environments of the delta while wearing the standard issue tropical boots plus the issue wool cushioned socks. To clarify this point-the native rice farmer rarely develops the condition because he wears sandals or goes barefooted and dries out his feet periodically during the day and at night. Its early symptoms are swelling of the entire boot area. The soles of the feet are dead white and soggy with deep wrinkles associated with moderate pain on walking. The rather severe symptoms resemble the foot of a drowning victim-the foot has swelling and is dead white in appearance. There is a painful burning surface when the feet hang down and they are exquisitely tender to touch. Frequently the top layer of skin comes off in silver dollar size patches where it is rubbed off at boot friction points. The entire sole is hardened, swollen and painful to walk on. The best treatment of this disease is prevention. Soldiers need bed rest and then gradual ambulation without boots. No medicine used internally or on the skin will influence immersion foot. The effects appear to be cumulative and several moderate episodes will result in the inability to wear boots and the men then require a permanent profile and are lost to infantry duty. Chart 3 shows the disabling effects of tropical immersion foot syndrome. This chart indicates that shortly after two days in the rice paddies a unit could generally become as much as 50 percent disabled. Thus the syndrome can be almost completely avoided by limiting exposure to 48 hours.

(3) Pyoderma Bacterial Skin Infections. There are always bacteria on the skin and the heat and humidity of the tropics is an excellent incubator. Minor skin injuries under these conditions are prone to secondary infections. No really effective solution was found to treat or to prevent bacterial skin infections, although a Walter Reed Army Institute of Research team had developed some very promising information just before the 9th Division departed

[31]

CHART 3-TROPICAL IMMERSION FOOT SYNDROME

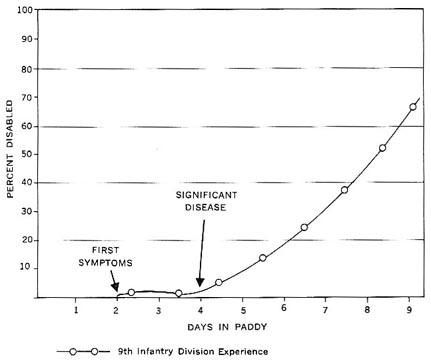

Vietnam. Chart 4 is an indication of the disabling effects of pyoderma bacterial infection.

The results of the tests for the 3rd Battalion, 47th Infantry are indicated in chart 5 for the period July through December 1968. It can be seen that once the 48 hour rule was initiated the incidence of immersion foot dropped to almost zero and that at no time did fungal infections become a major problem. However, the incidence of pyoderma continued to rise and became the major cause of lost time due to dermatological diseases. (The onset of the dry season also tended to depress the end figures).

The medical reporting system within the 9th Division was initially found to be defective in three major aspects. First, statistics reflecting time lost from duty because of disease were grossly inaccurate since they normally included only soldiers sick in quarters in medical battalion facilities and hospital admissions. Secondly,

[32]

CHART 4-PYODERMA-BACTERIAL INFECTION (FOOT AND BOOT AREA)

these reports were tabulated monthly and were not suited for the close day by day monitoring of a serious disease problem. Finally, the information often was based on inaccurate diagnoses because of the lack of dermatological experience in the physicians. To overcome these shortcomings a daily Dermatological Sick Call Report was required from each divisional medical treatment facility. This material was tabulated (Table 3) and forwarded to Division Headquarters with comments in a Weekly Dermatology Sick Call Summary. The same information in a shorter form was presented in the Weekly Administrative Briefing. These reports accomplished several important functions: they provided an accurate measure of the loss of combat strength due to skin disease, they provided a timely monitoring system for the commander, and served to increase the interest of medical officers and unit commanders in this serious problem.

The complete preventive dermatology program was interrelated, including medical diagnosis and treatment, administrative reporting and monitoring, and the most important component of command support. The single most important contribution to the solution of the problem was a directive on 28 October 1968 which limited

[33]

CHART 5-COMBAT MAN-DAYS LOST DUE TO DERMATOSIS, 3D BATTALION, 47TH INFANTRY, JULY-DECEMBER 1968.

combat operations to 48 hours (except in real tactical emergencies) followed by a 24-hour drying out period. This was a radical departure from normal Vietnamese practice which favored longer periods in the field for various cogent reasons.

"Operation Safe Step" proved that command supported practical medical research of significant medical problems was feasible in a

[34]

TABLE 3 - NINTH INFANTRY DIVISION WEEKLY DERMATOLOGY SICK CALL

REPORT SUMMARY PATIENTS/MAN DAYS LOST a

PERIOD 19-25 JUNE 1969

| Ninth Division Units | MDL All Med/Surg Causes | Dermatology Body |

Foot Disease-Patients/Man Days Lost |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Pyoderma |

B. Fungal |

C. Immersion Foot |

D. Other (Misc) |

Total Ft. Dis | |||||||||

| Pts | MDL | Pts | MDL | Pts | MDL | Pts | MDL | Pts | MDL | Pts | MDL | ||

| 6/31 Inf | 9 | 43 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 4 | - | 4 | - | 12 | - |

| 2/39 Inf | 175 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 14 | - | - | 27 | 35 |

| 3/39 Inf | 52 | 8 | - | - | - | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 23 | 20 |

| 4/39 Inf | 99 | 19 | 30 | 10 | 1 | 1 | - | 9 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 25 | 5 |

| 2/47 Inf | 139 | 53 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | - | - | 13 | 4 | 27 | 12 |

| 3/47 Inf | 139 | 11 | 24 | 12 | 17 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 28 | 43 |

| 4/47 Inf | 137 | 7 | 2 | 25 | 22 | 16 | 19 | 39 | 19 | 1 | - | 81 | 60 |

| 2/60 Inf | 32 | 12 | - | 4 | - | 8 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 16 | - |

| 3/60 Inf | 62 | 10 | 8 | - | - | 2 | - | 8 | 3 | 1 | - | 11 | 3 |

| 5/60 Inf | 92 | 15 | 11 | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 16 | 20 | 18 | 20 |

| Man Bn Tot | 936 | 188 | 106 | 76 | 67 | 51 | 35 | 83 | 54 | 58 | 42 | 268 | 198 |

| Average | 93.6 | 18.8 | 10.6 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 26.8 | 19.8 |

| Oth | 390 | 203 | 64 | 4 | - | 4 | 5 | - | - | 13 | 2 | 21 | 7 |

| Div Totals | 1326 | 391 | 170 | 80 | 67 | 55 | 40 | 83 | 54 | 71 | 44 | 289 | 205 |

a Man Days Lost (MDL) reports each day a soldier is medically unfit to perform in his MOS, includes Quarters, Limited Duty and No Paddy Duty

[35]

combat division in the field. The 9th Infantry Division rapidly developed a highly successful integrated program to manage the serious skin disease problems in the Mekong Delta that had eluded control in previous conflicts in tropical Southeast Asia.

As we began to get our unit strengths under control through use of the Paddy Strength Report, it became apparent that we had defensive missions assigned which were adversely affecting our ability to conduct offensive operations. For example, at one time, we had the following diversions: protecting US Army, Vietnam, ammunition unloading point, 1 company; defending signal relay site, (1 platoon), 1/3 company; defending POL tank farm (1 battalion) , 3 companies; defending a remote artillery position, 1 company; defending two major bridges, 1 company; and convoy protection, 1 company-a total of 71/3 companies.

These missions had accumulated over a period of time and were necessary. Initially, they were not too burdensome, as units which were tired or cut up could be diverted to these tasks and while

DEFENSIVE VIGIL

[36]

performing the defensive missions could rebuild and retrain. However, we began to see that regardless of the way it was handled that slightly over one-quarter of our divisional infantry units (7.3/27 = 27+ percent) were defending critical installations and not carrying the fight to the enemy directly. Fortunately, the division, in the spring and summer of 1968, was shifting into the delta, and some of these tasks were passed off to other units. As the overall security situation improved, some were simply terminated as no longer necessary. When the Government of Vietnam mobilized in 1968, regular South Vietnamese Army units or Regional Force and Popular Force units became available and took over some of the remaining tasks. Suffice it to say that after about six months, they had all been closed out, and the division was able to concentrate practically all of its units on offensive operations.

The effect of these efforts was most dramatically brought out in Long An Province. In early 1968 there were six rifle and three mechanized companies in Long An Province (three battalions). Three of these companies were on these defensive operations. As a result, each battalion had only two companies available for mobile offensive operations and all other missions. In effect, they were just barely keeping the enemy off balance and worried. During the Mini-Tet offensive against Saigon, the enemy was able to move three or four of the five Main Force battalions in Long An against Saigon and to put on a fairly creditable attack. In addition, Long An while the most populous and richest (rice-wise) province in all of III Corps was the least pacified. We decided we had to do better in Long An, and as a result in late June 1968, we moved our best brigade into the province with two very good "strike" battalions (2d Battalion, 39th Infantry and 2d Battalion, 60th Infantry) plus a mechanized battalion. Due to the previous culling out of defensive missions, these two battalions were able to devote almost 100 percent of their effort to mobile offensive operations and were able to break up the enemy battalions in Long An over a period of months.

The Mathematics of Troop Management

Each of the efforts mentioned previously achieved measurable results in isolation. However, taken all together, the increase in unit or troop availability was most impressive.

[37]

| March 1968 Unit Base | 3 to 4 Company Reorganization | 6th Battalion, 31st Infantry Addition | Mechanized Battalion Swap | |

| Infantry Companies | 7 X 3 = 21 | 7 X 4 = 28 | 8 X 4 = 32 | 9 X 4 = 36 |

| Mechanized Companies | 2 X 3 = 6 | 2 X 3 = 6 | 2 X 3 = 6 | 1 X 3 = 3 |

| 27 Cos. 100% |

34 Cos. 125.9% |

38 Cos. 140.7% |

39 Cos. 144.4% |

In looking at it from this point of view, the Division gained 44 percent in rifle companies, the majority of which (26 percent) resulted from the "squaring" reorganization based on the Army Combat Operations Vietnam evaluation, with the remaining 18 percent due to the other changes.

By a combination of refining unit missions and concentrating on the offensive we were able to reduce defensive effort and increase offensive effort. The mathematical improvement on a division basis was impressive.

| Spring 1968 | June 1968 | Spring 1969 | |

| Available Cos. | 27 | 31 | 39 |

| Offensive Effort | 50 percent | 66 percent | 66 percent |

| Companies on Offense | 13.5 | 20+ | 26 |

It can be seen that from a purely mathematical point of view the increase in offensive effort from both organizational and management improvements was in the neighborhood of 100 percent.

Before the Tet battles, the 9th Division was scattered over a large area. Its Tactical Area of Interest, the area which it overwatched, included all or part of at least eight provinces, and its Tactical Area of Responsibility included all or part of four large provinces. By late 1968, as the division moved south to the Upper Delta, both of these areas had been reduced to more manageable proportions. The following gives an indication of this concentrating effect:

| Pre-Tet TAOI (provinces) | Pre-Tet TAOR (provinces) | Late '68 TAOI (provinces) | Late '68 TAOR (provinces) |

| Long An | Long An | Long An | Long An |

| Dinh Tuong | Dinh Tuong | Dinh Tuong | Dinh Tuong |

| Go Cong | Go Cong | ||

| Bien Hoa | Bien Hoa (eastern) |

[38]

| Pre-Tet TAOI (provinces) | Pre-Tet TAOR (provinces) | Late '68 TAOI (provinces) | Late '68 TAOR (provinces) |

| Long Khanh | Long Khanh (western) | ||

| Phuoc Tuy | |||

| Binh Thuy | |||

| Gia Dinh (parts from time to time) | Kien Hoa | Kien Hoa | |

| Strategic Reserve IV Corps |

Strategic Reserve IV Corps |

Strategic Reserve IV Corps |

Strategic Reserve IV Corps |

Strategic Reserve Strategic Reserve Strategic Reserve Strategic Reserve IV Corps IV Corps IV Corps IV Corps

It should be noted that the geographical assignment of missions was not as simple or tidy as suggested. However, the chart does bring out that the division's geographical responsibilities became much more limited, thus permitting it to essentially focus ten battalions on three provinces. (Go Cong required little effort.) The psychological and intellectual focus was probably of equal importance. With more manageable areas and missions all commanders felt more confident and became more able to influence their situations. As a result, the impact of the brigades was improved markedly. For example:

Long An Brigade

In early 1968 because of static details only six companies out of the three battalions in Long An were offensively oriented. After squaring the battalions and shaking out the defensive missions about 8 of the 11 companies were committed offensively. The actual improvement was more than the figures would suggest, as the brigade commander was able to put on more and constant pressure and to react more quickly with his own resources.

The Riverine Brigade.

The historical Riverine method of operating can be described as three days of full effort and five of rest, rehabilitation, and training, or 37.5 percent offensive effort for six companies. After we understood paddy foot better and changed to the 48-hour exposure rule and added one battalion, the brigade effort was increased and fluctuated between a 66 and 75 percent operating rate for twelve companies with a quadrupling of offensive effort. Quite a jump!

The Dinh Tuong Brigade.

In the spring of 1968 this brigade could muster 2 battalions totaling 6 companies with 4 on offensive effort. By late 1968 it had

[39]

RIVERINE FORCE

3 battalions totaling 12 companies with 9 on offensive operations. This more than doubled their offensive effort.

In summary, by a combination of reorganizations, tight personnel

control, emphasis on offensive operations, "Operation Safe Step,"

and a more manageable mission, the division was able to increase

its offensive effort at least one hundred percent across the board.

These increased resources were then devoted to a more concentrated

effort due to the smaller area of responsibility.

If one were to draw up a set of rules for the 9th Division area,

it might be that the optimum solution would be:

A reasonable configuration for effective operations in a manageable

area would be ten 4-company rifle battalions at full strength.

Three-company rifle battalions resulted in a marked loss of

efficiency.

Seriously understrength rifle companies resulted in a loss of

efficiency.

A thirteen-battalion division would probably be the best arrangement

for operations giving a good balance between foxhole strength,

flexibility, and effective control with a low overhead ratio.

[40]

This is partially an intuitive judgment although based on good results obtained with four-battalion brigades from time to time.

It might be added that our experience in this area was that tight management, plus a continuing analysis of missions, areas of operation and organization brought about a maximizing of effort and very good control of operations.

An important element of our program for strengthening our units and improving their effectiveness was the Kit Carson Scout or Tiger Scout program. This program impinges on many aspects of our overall strengthening process and it is covered here only as a matter of convenience.

The Kit Carson Scout Program (which for unknown reasons was called the Tiger Scout Program in the 9th Division) was well known in Vietnam. It consisted of hiring Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Army soldiers who had defected (and were known as Hoi Chanhs), and integrating them in U.S. units. These defectors, who invariably were strongly anti-Communist once they had deserted, were used in rifle squads as riflemen or scouts. Their guerrilla skills, their local knowledge, familiarity with the local language, and their ability to communicate with the Vietnamese people made them invaluable. Unfortunately, their command of English was usually very limited, but after some contact with the unit in which they lived and fought, they were able to communicate rea-

TIGER SCOUT

[41]

sonably well. After having the advantage of good food, good medical care and the superior training of the U.S. units, they made first class soldiers.

In the spring of 1968, the 9th Division was authorized in the neighborhood of 250 Tiger Scouts. In theory, that put about two Tiger Scouts in each rifle platoon, but in practice we did not have as many as authorized. It had been our experience, heretofore, that it was difficult to recruit as many scouts as we were authorized. After assessing the advantages of the program and making a few trial runs, it was determined that the recruiting possibilities were actually quite good, but the program suffered from a combination of lack of attention by lower commanders and a certain subconscious uneasiness at having Communist defectors in frontline units. In any case, we started an organized recruiting campaign and were very rapidly able to have our authorization raised to somewhat over 400 scouts in the division. The direct cost to the U.S. Government was quite low as their pay scale, although attractive in Vietnamese terms, was quite modest.

The increased authorization and recruitment allowed us to put one Tiger Scout in each rifle squad, as well as specialists in intelligence and reconnaissance units and prisoner of war interrogation teams. One very direct bonus from this arrangement was that it automatically increased our rifle strength by ten percent, and counteracted the effect of U.S. soldiers being absent due to rest and recreation, sick call, and wounds. Not only did this device increase our rifle strength, but it had many indirect bonuses alluded to above. It obviously broke down the language barrier to a certain extent as the scouts could talk to prisoners, the local population, or to members of the Vietnamese armed forces. Not only could they converse with these people, but due to their knowledge of the country, they were able to solicit information from them that an American could never obtain in any case. They were also very good scouts-they had an intimate knowledge of Communist tactics and could, as a result, feel out situations by instinct which the inexperienced among the U.S. soldiers had to figure out the hard way. Interestingly enough, the Tiger Scouts proved to be extremely able and loyal members of the team. Although some of them were discharged due to illness or lack of ability, the number of scouts who deserted or were suspected of rejoining the Communist forces was extremely low, perhaps a handful at most. All in all, this was a most successful program as it not only strengthened our own units, but helped to soften some of the major difficulties inherent in a U.S. unit working in a strange country.

[42]

A recapitulation of the aforementioned six actions indicates the terrific impact that close management of units and personnel can have upon the operational effectiveness of a Division. After the May offensive against Saigon we reoriented our thinking towards the Delta. Our movement from the Bearcat area to Dong Tam commenced in early June 1968 and was completed in July. When we started our reorientation we had 21 straight-leg and 6 mechanized infantry companies available for combat operations; of these, seven and one-third were tied up on static missions and each company could field not more than 80 riflemen. Our infantry companies operated in the delta environment and in the jungle areas around Bearcat fifty percent of the time. This amounted, then, to about 780 infantrymen aggressively seeking the enemy on a daily basis.

After our reorganization to four-rifle company battalions, the windfall of another infantry battalion and the exchange of one of our mechanized battalions for another infantry battalion we ended up with 39 infantry companies. Additionally, as the result of intensive personnel management by the use of the Paddy Strength Report these companies had a minimum combat strength of 120 men. The flexibility afforded by the reorganization plus improved techniques in night operations allowed us to increase the tempo of operations to three companies per battalion in the field on a daily basis. This amounted to about 3,500 infantrymen breathing down Charlie's neck every day and night of the year-an increase of about 350 percent in the resources available for combat operations.

This rather slow and difficult process took from six to nine months to bring to completion. Obviously, the division was more effective. However, the real gain was to get the division up to its design Table of Organization and Equipment strength where it became a responsive and effective fighting machine.

[43]

page updated 19 November 2002

Return to the Table of Contents