CHAPTER III

Optimizing Army Aviation Assets and Support Facilities

In the Mekong Delta combat capability was directly correlated with Army Aviation assets. We soon found that we had little tactical success without helicopters. They provided mobility and fire power as well as surprise. The Air Cavalry troop was the eyes of the division and the "slicks" gave us our maneuverability. Since the tactical success of the division hinged so much on aircraft support, great command emphasis was placed on this vital area. We successively analyzed five major aspects of aviation: maintenance, combat effectiveness, aircraft allocations, tactics, and aircraft utilization. Operations Analysis was utilized to maximize each of these aspects of air operations.

We knew we needed more aircraft on a daily basis if we were going to improve our operational success. But before going to higher headquarters for assistance we decided to get our own house in order. This meant maximum utilization of organic aircraft, and you can't fly them unless they are flyable. Applying the maintenance lessons learned in mechanized units in Europe we attacked our aircraft maintenance problems. Little by little, these efforts proved successful and by July 1968 an integrated maintenance program had evolved. However, we had to wait until about November 1968 for the completion of some of the maintenance hangars at Dong Tam to put our total program into effect. We formalized what we were doing as an "Eight Point Maintenance Program," consisting of:

(1) Direct Supervision by the Division Aviation Officer.

(2) Decentralized

Maintenance.

(3) Reorganized Aircraft Distribution.

(4) Expanded Prescribed Load

Lists.

(5) Aggressive Management of Authorized Stockage Levels.

(6) Weekly

Maintenance Stand-down.

[44]

(7) Night Maintenance.

(8) Aggressive Management of Assets.

In actuality this proved to be the basic formula for the successful utilization of our aviation assets, both organic and attached. Since the program was so successful for our own aircraft, we later utilized it for attached and most supporting aircraft.

Direct Supervision by the Division Aviation Officer.

The operations of an infantry division are so diverse and there are so many decision-making centers that the organization almost violates the basic rule of sound management-manageable span of control. Under the normal division organization the commander must deal with many officers on aviation matters: the Aviation Officer, the Armored Cavalry Battalion Commander, the three brigade commanders, the Division Artillery Commander, and the Maintenance Battalion Commander. We decided early to place all our aviation assets under the supervision of the Division Aviation Officer for maintenance matters and to hold him responsible overall for the maintenance of aircraft. This did not include operational control which was retained by those units to which the aircraft were assigned. Every evening around 2200 hours the Division Aviation Officer was required to give a complete rundown of the status of all aircraft assigned to the division as well as his maintenance plans for the night. Since tactical planning depended to a great extent upon the availability of aircraft, this procedure allowed the G-3 to revise plans for the next day if necessary. Then again at 0700 hours at the morning briefing the Division Aviation Officer again provided a complete rundown of aircraft availability, incorporating all changes resulting from the night's maintenance. The summary chart utilized at the morning briefing is shown in table 4. Operational plans were again adjusted, if necessary, based on this information and on the intelligence picture.

Decentralized Maintenance.

Direct supervision by the aviation officer was greatly facilitated by attaching Company B, 709th Maintenance Battalion, the aviation maintenance company, to the 9th Aviation Battalion. We did this as part of a Department of the Army test that was supervised by the Army Concept Team in Vietnam. However, had there been no tests this step would have been taken because of the necessity to combine as much operations and maintenance as possible. We also expanded the maintenance operations of Delta Troop,

[45]

TABLE 4-9TH INFANTRY DIVISION DAILY AIRCRAFT AVAILABILITY

| Unit | Type | Assigned | Operationally Ready | Org Maint | Support Maint | % Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, 9th Aviation | UH-1D/H | 28 | 24 | 1 | 3 | 86 |

| B, 9th Aviation | UH-1C | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| AH-1G | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| LOH | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | ||

| U6-A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 87 | ||

| D Troop, | ||||||

| 3d Battalion, | ||||||

| 5th Cavalry | UH-1D/H | 7 | 6 | 0 | 1 | |

| AH-1G | 9 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||

| LOH | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 25 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 80 | ||

| 1st Brigade | LOH | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 75 |

| 2d Brigade | LOH | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 75 |

| 3d Brigade | LOH | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 75 |

| Division Artillery | LOH | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 86 |

| 9th Division | TOTAL | 88 | 73 | 10 | 5 | 83 |

3rd Battalion, 5th Cavalry and A Company, 9th Aviation Battalion so that they could perform third echelon maintenance. This decentralization of third echelon maintenance to three units was a real shot in the arm-the two major users maintained their own aircraft and B Company, 709th Maintenance Battalion provided maintenance for all the other units.

Reorganized Aircraft Distribution.

We soon learned that maintenance of a proper prescribed load list or authorized stockage level in a combat situation with the high turbulence in personnel and aircraft was a Herculean task. To facilitate this task the aircraft within the division were redistributed to have, as far as possible, only a single type aircraft assigned to each unit. Table 5 indicates the final aircraft distribution. Of the nine units involved, six ended up with only one type of aircraft, one unit had no aircraft, and two units had multiple type aircraft assigned. This redistribution facilitated maintenance, since most mechanics needed to familiarize themselves with only one type of aircraft and most prescribed load lists reflected only the parts of one aircraft type. Only Bravo Company, 9th Aviation Battalion and Delta

[46]

| Unit | Type Aircraft | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UH-ID/H | UH-1C | AH-1G | LOH | U6-A | TOTAL | |||||||

| TOE AUTH | ASGD | TOE AUTH | ASGD | TOE AUTH | ASGD | TOE AUTH | ASGD | TOE AUTH | ASGD | TOE AUTH | ASGD | |

| Co A, 9th Aviation Battalion | 25 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 28 |

| Co B, 9th Aviation Battalion | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 16 |

| B/709th Maintenance Battalion | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| D Trp, 3d Battalion 5th Cavalry | 6 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 25 |

| 1st Brigade | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 2d Brigade | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 3d Brigade | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Division Artillery | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 7 |

| 3d Battalion, 5th Cavalry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 35 | 35 | 4 | 4 | 15 | 15 | 34 | 34 | 0 | 2 | 88 | 90 |

[47]

Troop, 3d Battalion, 5th Cavalry ended up with more than one type of aircraft.

Expanded Prescribed Load Lists.

Our two highest density units were Co A, 9th Aviation Battalion and Delta Troop, 3d Battalion, 5th Cavalry. We received permission to expand their prescribed load lists to double the normal stockage. These expanded prescribed load lists went hand and hand with third echelon maintenance capabilities and insured the division the capability of performing most of its sophisticated maintenance right in these units. The expanded prescribed load lists cut our maintenance down-time in half in these units.

Authorized Stockage Lists.

The Authorized Stockage List for aircraft parts was broken out from the card deck of the 709th Maintenance Battalion. The concept was to have two separate decks, both supported by the single repair parts dedicated NCR 500 computer. Ideally both decks (aviation and general parts) should have been run through a daily cycle but because the NCR 500 was overloaded and because we were running so many research programs on the machine it was possible to cycle only the aviation repair parts deck on a daily basis. Every day of the week parts runs were made by helicopter and by wheeled vehicle. We maintained a liaison sergeant at the Aviation Maintenance Management Center run by the 34th General Support Group. The liaison thus established was invaluable and the support provided by the 34th Group was of the highest order.

Weekly Maintenance Stand-dozen.

From the aforementioned one might presume that repair parts were the guts of maintenance. That is the truth! Yet even with enough repair parts we found out that operational necessity generally overrode maintenance procedures and aircraft were not getting their periodic inspections as scheduled. Therefore, we initiated an inviolate weekly maintenance stand-down-thus one-seventh of the choppers in the division stood down every day. This paid off handsomely because it enabled maintenance to be performed on minor faults before they became major problems. The weekly stand-down kept our choppers flying out of all proportion to the down-time lost.

Night Maintenance.

The majority of aircraft were utilized in daytime operations. The Light Observation Helicopter (LOH), for example, was generally not useful at night and unless there was a night raid

[48]

HELICOPTER MECHANICS

scheduled, very few Huey UH-1D or UH-1H models were utilized at night. Since the LOH's and Huey's were about 80 percent of our aircraft it was apparent we had to perform maintenance at night in order to fly more during the day. However, without adequate facilities nighttime maintenance was impossible. Therefore, the first order of priority in the construction of Dong Tam was the provision of adequate hangars. The lights in these hangars burned all night every night-mortar attack or not. Naturally this twenty-four-hour-a-day maintenance took careful personnel scheduling but the morale of the mechanics was high and the pride they took in their work was extraordinary. We rewarded the fine work of the aviation mechanics by various forms of recognition, but few people in the division realized how much they owed to this dedicated group of soldiers.

The aforementioned Eight Point Maintenance Program boils down to just common sense; centralized control, reorganization as required, efforts placed at critical points, and firm and aggressive management. Not apparent in this discussion are all the extremely complex operations required to milk repair parts out of a sluggish

[49]

PICKUP ZONE

system, to insure that reports were proper, to schedule periodics so that maintenance was performed, to keep Prescribed Load Lists up to date, to anticipate problem areas, and to inspire the men who performed this around-the-clock repetitive day-to-day maintenance. The net result of the Eight Point Maintenance Program was to raise the availability of aircraft in the 9th Division from around 50 percent to a level consistently above 80 percent. This increase in

[50]

PICKUP ZONE

aircraft availability provided commanders with a degree of flexibility that enabled several new tactical techniques requiring aviation support to be tested.

Aggressive Management of Assets.

The 9th Division did a lot of pre-planning but it also maintained maximum flexibility. We reacted quickly to good enemy intelligence; these reactions had to be swift to be effective. Most reactions were dependent upon aviation assets. Therefore we established within the Division Tactical Operations Center an organization with the responsibility for controlling every aircraft, both organic and attached, at all times. We called this our Air Control Team, whose acronym ACT was the essence of their responsibilities. They were provided with the best communications equipment available as well as sharp and aggressive officers. Through the ACT, aircraft could be diverted on a moment's notice from any portion of the division's area of operations to a new mission and we could expect that the subsequent mission would be accomplished rapidly because of the tight management of assets. Although Hueys were assigned and utilized on a decentralized basis it was understood that any aircraft could be recalled on the order of the Air Control Team. No aircraft was held in reserve or on standby.

It was natural that our first analytic efforts concerning aircraft availability should be directed toward maintenance, because initi-

[51]

ally it affected our organic assets the most. However, the preponderance of our tactical aviation support was allocated to us by higher headquarters and our combat efficiency was in great part tied to these allocations. During the summer and fall of 1968, II Field Force Vietnam normally allocated us two assault helicopter companies and an air cavalry troop daily. Considering stand-downs and diversions to other units this averaged approximately 53 assault helicopter company days per month and 22 air cavalry troop days per month. When the II Field Force Vietnam air cavalry assets were combined with the organic Delta Troop 3d Battalion, 5th Cavalry it gave us about 48 air cavalry days per month. Thus with three brigades in the field at all times this meant that every day at least one of the brigades was without helicopter support. We had found that the best combination was to provide a brigade with both an air cavalry troop and an assault helicopter company under its operational control. During the summer of 1968 the main thrust of all our tactical planning was to determine the greatest enemy threat or the most lucrative intelligence target so that we could allocate our scarce air assets to obtain the maximum results. The brigade in Long An Province because of its strategic location south of Saigon and its nearness to the Cambodian Border received the lion's share of the helicopter assets-25 days a month. The brigade in Dinh Tuong Province had helicopter assets an average of 17 days a month and the Riverine Brigade operating in Kien Hoa Province received helicopter assets an average of only 8 days per month. Although the Viet Cong capabilities in Dinh Tuong and Kien Hoa were about the same, the Riverine force had some "built-in" mobility due to their naval assault craft while the brigade in Dinh Tuong was on foot-thus the difference in the allocation of assets.

In mid-August 1968 we found that the use of the "People Sniffer" (Airborne Personnel Detector) was giving us good results in finding Viet Cong. At the time we were probably one of the few units in Vietnam that thought highly of the People Sniffer. In retrospect the reason was undoubtedly that the terrain in the delta was ideal for the device as compared to jungles and hilly country throughout most of the rest of Vietnam. Consequently, in the fall of 1968 we began to distribute People Sniffer equipment to each brigade on a daily basis to assist them in locating the enemy. In our normal tactical configuration the People Sniffers were carried in a slick belonging to the supporting Air Cavalry Troop and the People Sniffer runs were an integral part of the search techniques of the troop. To give each brigade a daily People Sniffer capability meant simply that we had to make up a reconnaissance team from

[52]

organic aviation assets. This additional team paid off handsomely in operational results-it gave us an additional nose and pair of eyes but we were still limited in troop carrying assets and gunships. Thus, we followed up lucrative targets by diverting our scarce aviation assets to the hottest target.

It became obvious to any casual observer that when a brigade had aircraft assets, particularly both the air cavalry and the slicks, that its tactical success was greatly enhanced; consequently, we made a systematic study of the effectiveness of the helicopter in combat operations. This study, which is discussed in the next section, proved conclusively that a brigade with chopper assets was much more successful than one without chopper assets. So, we started beating the drums with higher headquarters to get more air assets. Fortunately, we received a welcome break from IV Corps Tactical Zone. Major General George S. Eckhardt, the IV Corps Senior Advisor, had conceived a "Dry Weather Campaign" whose purpose was to make an all out push during the dry weather season in the delta to deal a decisive blow to the Viet Cong in this heavily populated and rice rich area of Vietnam. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, agreed to the major aspects of this program, including the provision of additional air assets. Commencing in January 1969 the 9th Division thus received a third Assault Helicopter Company and a second Air Cavalry Troop (for a total of three) on a daily basis. Thus, for approximately 26 days a month every brigade had the optimum helicopter support-an Air Cavalry Troop plus an Assault Helicopter Company. This roughly amounted to a 40 percent increase in gross supporting assets. In our opinion, receipt of these additional aircraft was perhaps the most important factor in increasing the combat efficiency of the division.

In addition to our attached helicopter support, by the fall of 1968 we had improved our aircraft maintenance to the point that our organic assets could provide slicks as well as additional improvised air cavalry to our brigades on the days that we did not receive our full ration of attached or supporting aviation. This gave us an additional 15 percent push in the use of aviation assets. On top of that it enabled us to increase our stand-by aircraft for counter-mortar alerts at night and it gave us the capability within division resources to implement some very sophisticated night tactics which evolved in the early part of 1969.

Commencing in January 1969, then, we had maximum coverage of our area of operations in every brigade area utilizing our daytime intensive reconnaissance and air assault techniques. Additionally, in at least two brigade areas we had night coverage which enabled us to

[53]

interdict Viet Cong movement of supplies and personnel. As a result of this continuous day and night pressure Charlie became unglued in March 1969 and we took him apart completely in April 1969. The increased availability of aircraft as well as our finely honed tactical concepts were keys to these tactical successes.

Improvements in Combat Efficiency Resulting from Additional Aviation Assets

As we began to get a good feel of those areas affecting combat operations that needed systematic analysis we decided to bring a sharp officer into the Command Section to perform operational analysis on a full time basis. During a period of little over a year we successively utilized three outstanding officers, Major Edwin A. Deagle, Jr., Major John O. B. Sewall, and Major Jack O. Bradshaw. Because of the importance of aviation assets we set Major Deagle on the problem of measuring the improvements in combat efficiency which could be directly related to the input of airmobile resources. Major Sewell performed several studies, one of which, "Jitterbugging Operations," he has presented at Fort Benning. Major Bradshaw produced an outstanding compendium of combat statistics and also documented historical data to support a Presidential Unit Citation submission.

The study concerning improvements in combat efficiency resulting from airmobile assets was particularly informative. We defined our combat environment as one in which the enemy sought to avoid contact. This was our normal situation after the high point of Tet 1968 and with few exceptions after that time did the enemy ever mass for major sustained attacks. We concluded then, and continued to believe, that the most direct statistical index of combat efficiency which could be isolated was the damage measured in the number of enemy losses (prisoners of war, Hoi Chanhs and killed-in-action) inflicted on the enemy by a unit in the field.

We recognized that combat efficiency, as defined here, provided no indication of the number of our own battle casualties sustained while inflicting losses on the enemy; therefore, we also included an analysis of our own casualty rates.

The term "airmobile assets" required precise definition. In literal terms, it would have to include assault lift elements, airborne and air transported fire support, command and control aircraft, reconnaissance aircraft, and airmobile logistic support elements. To simplify the analysis, it was assumed that the provision of all types of airmobile resources except assault helicopter units and air cavalry units was reasonably uniform and thus did not materially in-

[54]

fluence combat performance from day to day. "Airmobile assets" was therefore defined to include Assault Helicopter Companies and Air Cavalry Troops only.

It was the policy in the division to give commanders maximum control of their combat assets. As a result the Assault Helicopter Companies and Air Cavalry Troops were allocated to the brigades on a daily basis and placed under their operational control. Therefore, it was only natural to use the brigade as a basic maneuver unit in a measurement of combat effectiveness of air assets. The study included a total of 313 brigade-days of combat during the period 7 March through 15 August 1968. We hasten to point out that this was an early period of operations before our paddy strength was up and long before we had perfected our tactical innovations. The period was good for statistical purposes but in subsequent months we refined our operations to the point that we expected and received much better results than were obtained during this period.

With no airmobile or air cavalry support, the three brigades averaged 0.21 significant enemy contacts per day spent on field operations. When supported by either an Air Cavalry Troop or an Assault Helicopter Company, brigade performance did not change appreciably, or in any case was not statistically consistent. However, when supported by both an Air Cavalry Troop and an Assault Helicopter Company, average brigade performance more than doubled, to a figure of 0.49 contacts per day. In other words, with no air assets, a brigade averaged a significant contact with the enemy only once every five days; with an Air Cavalry Troop and an Assault Helicopter Company, it developed contact every other day on the average.

Analysis of Viet Cong losses per field day produced more definitive inferences. With no air assets, brigade performance averaged 1.6 Viet Cong losses per field day-hardly a creditable return. With an Air Cavalry Troop, this figure rose to 5.1 Viet Cong per day: an increase in performance of 218%. With an Assault Helicopter Company, performance averaged 6.0 Viet Cong losses per day. It is doubtful that the difference in performance between operations supported by an Air Cavalry Troop and those supported by an Assault Helicopter Company are statistically significant. However, when a brigade was supported by both an Air Cavalry Troop and an Assault Helicopter Company, brigade performance rose to 13.6 Viet Cong losses per day-an increase of 750%. The striking rise in efficiency when both assets were present supports the idea that performance with both assets tends to be somewhat more inde-

[55]

pendent of the leadership styles of the brigade commanders than with either asset alone.

Enemy losses are most meaningful as an indicator of performance when they are compared with friendly losses. It was our desire in the 9th Infantry Division to maximize our capabilities to damage the enemy, with heavy emphasis on prisoners and Hoi Chanhs, and to minimize our own personnel losses. The ratio of enemy losses to friendly losses, then, was considered to be an excellent measure of combat output.

The following table compares the total Viet Cong eliminated with U.S. Killed by Hostile Action as well as U.S. Killed by Hostile Action and Wounded by Hostile Action during the period of the study in the spring and summer of 1968.

TABLE 6-COMBAT STATISTICS MARCH-AUGUST 1968

| Forces | Ratio of Enemy Losses to U.S. KHA | Ratio of Enemy Losses to U.S. KHA plus U.S. WHA |

|---|---|---|

| With no air assets | 8.2 | 0.54 |

| With an Air-Cavalry Troop only | 10.5 | 1.60 |

| With an Assault Helicopter Company only | 10.3 | 1.70 |

| With both Air Cavalry Troop and Assault Helicopter Company | 12.9 | 2.50 |

It is obvious that air assets not only enhanced the results of brigade operations, but they also enabled us to reduce our own casualties relatively thereby increasing our combat efficiency. We could not be insensitive to total U.S. casualties and Table 6 shows that the overall cost in wounded and killed U.S. personnel was radically reduced when air assets were available as compared to slugging it out on the ground. This is not particularly startling because the increase in maneuverability, fire power and observation was bound to make operations more effective and enable us to protect our troops to the utmost. Thus in terms of inflicting damage to the enemy as well as protecting our own personnel, the capability of an infantry brigade in Vietnam was greatly enhanced by the use of airmobile assets. (Later on it was possible to reduce friendly KHA absolutely as well as relatively.)

The brigade's statistics can be extended into a measurement of divisional effectiveness simply through an additive process. Using the situation in which no air assets are available as an index, the division's combat results would be:

1.6 + 1.6 + 1.6 = 4.8 Viet Cong losses per day

[56]

With one Air Cavalry Troop it would become:

1.6 + 1.6 + 5.1 = 8.3 Viet Cong losses per day

Similarly, with two Air Cavalry Troops the Viet Cong losses would increase to 11.8 per day, and with three Air Cavalry Troops the division could be expected to average 15.3 Viet Cong losses per day-an improvement of 218 percent over results with no aviation assets.

Similar calculations can be made for any combination of Assault Helicopter Companies and Air Cavalry Troops-up to three of each. It is pertinent, given the apparent complementary nature of the two assets, to look at the rate of increase in performances for increments of both assets:

One Air Cavalry Troop and one Assault Helicopter Company 16.8 Viet Cong losses per day

Two Air Cavalry Troops and two Assault Helicopter Companies 28.8 Viet Cong losses per day

Three of each: 40.8 Viet Cong losses per day

From the 9th Division's point of view, the last figure is the most significant. During the periods examined, the division was allocated on the average slightly less than two Air Cavalry Troops and two Assault Helicopter Companies per day (including the organic Air Cavalry Troop) . Had the allocation been three of each (one for each brigade) , it is estimated that the division's combat effectiveness for that period would have increased by approximately 40 percent. Moreover, brigades could have been expected to improve further over time since planning would not have been disrupted by last-minute changes in support priorities among the three brigades. Daily operations with the same supporting air units greatly enhanced co-ordination and professionalism-the brigades in effect moved rapidly up the learning curve (a phenomenon which reportedly is inherent to airmobile division units). It is difficult to imagine how similar inputs of any other type of resources (artillery, infantry, etc.) would have generated an equivalent improvement in combat performance.

It is probable that not all divisions in Vietnam would have achieved statistical improvements similar to those of the 9th Division. The inundated flatlands of the Mekong Delta have a double edged impact on the mutual effectiveness between foot and airmobile operations. Marshy swamps and. flooded rice paddies severely penalize ground troops. Units frequently are able to move no more than 500 meters per hour or less. On the other hand, the broad stretches of virtually flat delta country provide an ideal environment for the unrestricted employment of Army aviation. Pre-

[57]

sumably such would not be the case in other areas of Vietnam, but unquestionably the allocation of additional airmobile assets to provide each combat brigade on a daily basis with an Assault Helicopter Company and an Air Cavalry Troop would have increased combat results by a meaningful amount. The actual increases in combat efficiency resulting from the assignment of an Assault Helicopter Company and an Air Cavalry Troop to each brigade have been measured for 9th Division operations and will be discussed in a subsequent section on the payoff of increased Army aviation assets.

The 9th Division, largely due to a large number of very skillful combat leaders, was particularly innovative in adapting standard tactical techniques to the delta terrain. With respect to the use of aviation assets we fostered several tactical techniques, but they all stemmed from two fundamental changes that materially enhanced our operational capabilities.

As was stated previously, by the fall of 1968 the Viet Cong in our area had broken down into small groups and were avoiding combat at all costs. Consequently, our airmobile assault techniques utilizing an entire Assault Helicopter Company with supporting air cavalry elements were proving ponderous. We wanted to break down into smaller more flexible units in order to be able to cover a larger area and to apply more constant pressure on the enemy. However, airmobile doctrine dictated that each assault be accomplished by 9 or 10 slicks covered by two light fire teams (4 Cobras or other gunships). Consequently, we mustered our thoughts in this matter and briefed Major General Robert R. Williams, the 1st Aviation Brigade Commander, on the desirability of switching to five slick insertions instead of the usual ten. This had drawbacks for the aviation personnel since it required twice as many trained lead ship personnel. However, General Williams gave us the go ahead on a trial basis and we commenced jitterbugging with five slick insertions. The immediate effect was dramatic. We were able to check out twice as many intelligence targets. We were able to cover broader areas thereby almost doubling the amount of pressure brought to bear on the Viet Cong. Later on, in 1969, when we had chopped up the Viet Cong even worse and scattered them to a greater degree it was commonplace to make 2, 3 and 4 slick insertions without fear of undue casualties in either aircraft or infantry personnel. The single technique of breaking down into smaller assault groups in late October 1968 had extremely far reaching

[58]

implications for our tactical success. Like many new ideas it had been done before but on a rather selective basis. The new idea was to do it all the time.

The second fundamental change in techniques involved our Air Cavalry Troops, perhaps the most important ingredient in strike operations. As our maintenance improved and the availability of aircraft became greater we split our organic 3d Battalion, 5th Cavalry Troop into two teams. Initially the purpose was to provide daylight reconnaissance for all three brigades when one of our normal supporting Air Cavalry Troops was standing down for maintenance. Subsequently, we evolved night tactics tailored to the

MINIGUNS

[59]

use of air cavalry which proved tremendously effective. Our Night Search, Night Hunter and Night Raid techniques, combined with infantry night ambushes, "Bushmaster" and "Checkerboard" tactics, enabled us to keep an around the clock pressure on the enemy. These tactical techniques will be discussed in detail later. Because of our day and night operations we needed two air cavalry teams a day team and a night team. The nucleus of the day team were the scouts (LOH 6's) . There was much argument over whether the scouts should work in pairs under the protection of one Cobra or should work as a Scout-Cobra team. It was our experience in the delta that scouts working in pairs gave optimum coverage and due to the nature of the terrain and sparseness of vegetation that one Cobra could more than adequately provide cover for two scouts. There were others, however, who were in favor of the usual Scout-Cobra Team. Our day teams, then, normally consisted of 1 Command and Control ship, 2 Cobras and 4 Scouts.

On the other hand the Night Search and Night Hunter technique required 1 Command and Control copter and a light fire team (2 Cobras and a Huey flare ship if the ambient light was insufficient to activate our night vision devices). The Night Raid required a Command and Control copter and a light fire team plus 2 or 3 Hueys to insert a small element of combat troops. The total requirements for the Air Cavalry Troop, night team plus day team, amounted to approximately 50 percent of their assets and was met easily on a daily basis.

When our organic as well as supporting units (we cannot speak too highly of the 7th Battalion, 1st Air Cavalry Squadron for their ability to support night operations and the 214th Aviation Battalion for their all-around support) had broken down into the two team concept it literally took the night away from the Viet Cong. This, coupled with the expanded daytime air assault capability, optimized our tactical use of Army aviation air assets.

The two aforementioned simple but highly effective techniques revolutionized airmobile operations in the delta and allowed us to apply relentless pressure, heavily interdicting Viet Cong troop and supply activities as well as weakening his forces to the maximum degree.

Utilization of Army Aviation Assets

As we improved our maintenance and got locked in on our new tactical techniques it appeared as if our major unresolved problem with army aviation was "How much average flying time does it take to adequately support tactical missions?." To get a handle on

[60]

this question we did a rather exhaustive analysis taking into consideration the tactical techniques- and actual aircraft support provided the division by organic and assigned aviation assets. The premise underlying our analysis was that we would have one Air Cavalry Troop and one Assault Helicopter Company per brigade daily plus our organic divisional aviation assets. We considered that maintenance was such that at least 70 percent of the aircraft would be "mission ready" daily. We went about the study on a mission oriented basis, analyzing optimum daily requirements.

Air Cavalry Troop.

We considered a day team and a night team as previously discussed. We felt that the day team should be augmented at least 15 days per month by either the Air Cavalry Troop aero rifle platoon or by 4 Air Cavalry Troop slicks to carry our own infantrymen since some of the air cavalry squadrons were not organized with an aero rifle platoon while others were. On Jitterbugging Operations the use of 4 slicks with aero scouts or organic troops would give us a 50 percent additional troop carrying capability, thus increasing area coverage.

With respect to night team operations we felt that we could conduct eight Night Raids a month when slicks would be required to transport the raiding troops. On the other hand the Night Search and Night Hunter would require only one Command and Control copter and a light fire team (two Cobras). The results of our analyses are shown in Table 7.

SLICKS

[61]

SLICKS

[62]

TABLE 7-UTILIZATION STATISTICS AIR CAVALRY TROOP

| Daily Aircraft Requirements | |||||

|

U H-1 C&C |

B/D/H Slicks |

AH-1G | OH-6A | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day Team | 1 | 4a | 2 | 4 | |

| Night Team | 1 | 2b | 2 | - | |

| Total Requirement | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 13c |

| Assigned | 8 | 8 | 9 | 25 | |

| Aircraft utilized | 62% | 50% | 44% | 52% | |

| a-15 days/month b-8 nights/month c-Only 1 C&C and 4 slicks need to be mission ready |

|||||

|

Hours Per Aircraft Per Day |

||||

| UH-1B/D/H | AH-1G | OH-6A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | Slicks | |||

| Day Team | 8 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Night Team | 4 | 3 | 4 | - |

|

Total Hours Per Month |

|||||

| UH-1B/D/H | AH-1G | OH-6A | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | Slicks | ||||

| Day Team | 240 | 480 | 960 | 2040 | |

| Night Team | 120 | 240 | - | 408 | |

| Total Hours | 360 | 720 | 960 | 2448 | |

| Aircraft Assigned | 8 | 8 | 9 | 25 | |

| Hours Per Aircraft | 96 | 90 | 107 | 98 | |

|

Pilot Hours Per Month |

||||

| UH-1B/D/H d | AH-1G | OH-6A | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Aircraft Hours | 768 | 720 | 960 | 2448 |

| No. of Pilots | 18 | 15 | 9 | 42 |

| Avg Hrs per pilot | 85 | 96 | 106 | 96 |

| d-Two pilots per aircraft | ||||

It can be seen that on the average only 52 percent of the Air Cavalry Troop aircraft are committed on a daily basis and that the maximum flying time for any aircraft is 8 hours. The total hours per aircraft per month averaged out to approximately 98 hours. Pilot time averaged 96 hours per month, well below the 140 maximum stipulated by regulations.

Assault Helicopter Company.

The mission of the Assault Helicopter Company is rather cut and dried at first glance; they transport the troops and supplies to

[63]

TEAM OF AIR WORKHORSES

the target area. When utilized as a single entity, the Assault Helicopter Company normally provides one Command and Control copter, ten slicks, and two light fire teams comprised generally of four Charlie models (in 1968). However, the jitterbugging tactics of the 9th Infantry Division normally involved five slick insertions. Under these circumstances it became routine to break the Assault Helicopter Company into two teams of five slicks each. However, the Command and Control copter and the light fire teams normally accompanied each insertion of the five slicks, so that in reality there was a shuffling effect with the troop-carrying choppers. When insertions were made in two dispersed geographical areas, it proved advantageous to have the Air Cavalry Troop cover one insertion and to have one Light Fire Team from the Assault Helicopter Company cover the other. The Bounty Hunters of the 191st Assault Helicopter Company did this with extraordinary results. In such a situation, the ten slicks and two Charlie models would set down awaiting a new insertion while the Command and Control copter circled overhead with the Assault Helicopter Company and infantry battalion commanders and the other Light Fire Team provided troop cover. The aircraft and hour requirements for an Assault Helicopter Company are indicated in table 8. It can be seen that daily aircraft requirements for the Assault Helicopter company are slightly above those for an Air Cavalry Troop, both in percent of

[64]

TABLE 8-UTILIZATION STATISTICS ASSAULT HELICOPTER COMPANY

| Daily Aircraft Requirements | ||||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | Slicks | |||

| Requirement | 1 | 10 | 4 | 15 |

| Assigned | 19 | 7 | 26 | |

| % Aircraft utilized | 58% | 57% | 58% | |

|

Hours Per Aircraft Per Day |

|||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | Slicks | ||

| Hours | 10 | 5 ¾ | 6a |

| a-Two at 614 hours and two at 53/4 hours. | |||

| Total Hours Per Month | ||||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C&C | Slicks | |||

| Hours | 300 | 1725 | 720 | 2745 |

| Aircraft Assigned | 19 | 7 | 26 | |

| Hours per Aircraft | 107 | 103 | 105 | |

| Pilot Hours Per Month | |||

| UH-1B/D/H b | UH-1C b | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Aircraft Hours | 2025 | 720 | 2745 |

| No. of Pilots | 44 | 23 | 67 |

| Avg Hrs per Pilot | 92 | 63 | 82 |

| b-Two pilots per aircraft. | |||

aircraft utilized and in total hours per month, although the average pilot hours per month are less. It is interesting to note that about October 1968 higher headquarters authorized the Division to use its supporting Assault Helicopter Companies 2700 hours per 30 day period. This gave the Division much greater flexibility in that our commanders could use the assault aircraft for long periods when there was a good contact and could cut the flying short when the enemy was not to be found. In order to do this we used a 30-daymoving-average of 2700 aircraft hours which smoothed out humps and valleys. Our own analysis showed that under optimum conditions the average monthly requirement per Assault Helicopter Company was 2745 hours. Quite often intuitive judgment hit requirements right on the head even at higher headquarters.

Organic Divisional Aviation Assets.

The missions of our organic divisional aviation assets varied greatly. By and large, slicks were used as Command and Control

[65]

TABLE 9-UTILIZATION STATISTICS ORGANIC DIVISION AVIATION ASSETS

|

Daily Aircraft Requirements |

|||||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | AH-1G | OH-6A | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requirement | 18 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 39 |

| Assigned | 28 | 4 | 6 | 23 | 61 |

| % Aircraft utilized | 64% | 50% | 66% | 65% | 64% |

|

Hours Per Aircraft Per Day |

||||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | AH-1G | OH-6A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | 6 | 4 a | 5 b | 5 |

|

a-Night stand-by b-Night search, night hunts, Ranger insertions and extractions |

||||

|

Total Hours Per Month |

|||||

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | AH-1G | OH-6A | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | 3240 | 240 | 600 | 2250 | 6330 |

| Aircraft Assigned | 28 | 4 | 6 | 23 | 61 |

| Hours per Aircraft | 115 | 60 | 100 | 98 | 104 |

|

Pilot Hours Per Month |

|||||

| UH-1B/D/H a | UH-1C c | AH-1G c | OH-6A | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Aircraft Hours | 3240 | 240 | 600 | 2250 | 6330 |

| No. of Pilots | 63 | 8 | 18 | 24 | 113 |

| Avg Hrs per Pilot | 103 | 60 | 67 | 94 | 92 |

| c-Two pilots per aircraft | |||||

aircraft and performed essential maintenance and administrative functions including courier runs, day and night utility runs, and night radar repair ship. The gunships and Cobras generally were utilized on night standby to react immediately to enemy initiated incidents and as a night air cavalry team in support of the brigades on either Night Search or Night Raid operations. Because of the diversity of tasks, our assessment of utilization was based on a reasonable slice of assigned aircraft. We thought that about two thirds of all assigned aircraft should be operationally committed on a daily basis. The aircraft and our requirements are indicated in table 9. It can be seen that 64 percent of the aircraft were utilized and the total hours per aircraft per month were 104.

Summary.

Table 10 summarizes operational requirements and hours per month for aircraft for all type units:

[66]

TABLE 10-OPERATIONAL REQUIREMENTS, HOURS PER MONTH PER AIRCRAFT

| UH-1B/D/H | UH-1C | AH-1G | OH-6A | Avg Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Cavalry Troop | 96 | - | 90 | 107 | 98 |

| Assault Helicopter Companies. | 107 | 103 | - | - | 105 |

| Organic | 115 | 60 | 100 | 98 | 104 |

| USARV Avg (Feb 69) | 74 | 64 | 59 | 68 | 67 |

The total average requirements varied between 98 and 105 hours. We took a standard of 100 hours/aircraft/month, then, as a utilization rule of thumb. The U.S. Army Vietnam average was much below this-approximately 67 hours per month. The utilization standard we established would require a 50 percent increase in general aircraft utilization over the U.S. Army Vietnam figure. As a matter of interest, a detailed test was conducted in II Field Force later on, which demonstrated that efficient aircraft usage peaked at about 103 or 104 hours per plane per month, as contrasted to the 70 hours per month previously considered as optimum.

Actually, the utilization of aircraft for the months of February and March 1969 in support of the 9th Division amounted to 93.1 percent of this established standard. The only major shortfalls were in the use of Scout aircraft by the Air Cavalry Troops and in the use of organic Huey assets. The theoretical standard was based upon proven tactical usage and reasonable aircraft availability factors (about 60 percent daily) . Since actual performance compared favorably with the standard, we felt that the aircraft utilization in the 9th Infantry Division was about optimized with respect to flying hours.

A review indicated that by December 1968 the flying hours were also about optimized. We got a big shot in the arm when our organic and support aviation moved to Dong Tam, enabling us to operate from a central base location. We also improved our techniques in pre-positioning fuel and ammunition at outlying base camps in order to cut down on aircraft refueling and rearming time. Therefore, our aircraft assets were operating as efficiently as we knew how by making every flying hour count towards tactical operations.

To improve our tactical effectiveness we knew that we had to increase our aviation assets. We started out in our own backyard by implementing the "Eight Point Maintenance Program." The

[67]

result was an increase of our aircraft availability, both organic and attached, from 50 to 55 percent to about 80 to 85 percent on a daily basis, enabling us to split our air cavalry assets, forming a day team and a night team. Initially, however, until we obtained a third Air Cavalry Troop we used both organic teams for daylight operations.

Fortunately, the IV Corps Dry Weather Campaign which commenced in January 1969 gave us an additional Assault Helicopter Company and an Air Cavalry Troop. This optimized our tactical aircraft support, allowing an Air Cavalry Troop and an Assault Helicopter Company to support each brigade on a daily basis. Again, improved maintenance of our Hueys allowed us to parcel out 4 or 5 slicks to one of the brigades on those days when a supporting Assault Helicopter Company was standing down, thus keeping up the operational momentum.

In the late fall of 1968 we obtained permission from the 1st Aviation Brigade to split our supporting Assault Helicopter Companies so that we could have twice as many insertions and thus cover a broader area bringing more pressure to bear on the enemy. Throughout this period we were refining our tactics, increasing our aircraft availability and upping our flying hour utilization so that by February and March 1969 we were averaging over 93 hours per aircraft per month. As a result of the move to Dong Tam and the prepositioning of fuel and ammunition we were able to insure that our flying hours were most productive in supporting combat assaults.

All of this increased our combat performance. Recalling our study which measured the combat efficiency directly related to the inputs of airmobile resources, let us compare actual results with predictions. We found an appreciable increase in the efficiency of a brigade depending on the amount of aircraft under their operational control. In terms of actual results achieved by a brigade: with no air assets 1.6 Viet Cong would be eliminated per day; with an Air Cavalry Troop only 5.1 should be eliminated (we have projected that this figure is valid for both daytime and nighttime operations) ; with one Assault Helicopter Company only, 6.0 Viet Cong should be eliminated daily; and with an Air Cavalry Troop and an Assault Helicopter Company 13.6 Viet Cong should be eliminated daily.

The table below indicates the brigade days of available assets for the period December 1968 through May 1969.

There was little increase in assets between July 1968 and December 1968 when we had Air Cavalry Troops 48 days a month and Assault Helicopter Companies 53 days a month. However, as explained above, this changed dramatically in January 1969 with

[68]

TABLE 11-BRIGADE-DAYS WITH AIRCRAFT ASSETS, THEORETICAL COMPUTATION OF VIETCONG ELIMINATED

| Assets | Factor, VC Eliminated per brigade per day | Brigade-Days Month | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 68 | Dec 68 | Jan 69 | Feb 69 | Mar 69 | Apr 69 | May 69 | ||

| Air Cavalry Troop & AHC | 13.6 | 48 | 48 | 81 | 87 | 90 | 70 | 65 |

| Assault Helicopter Company Only | 6.0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| Air Cavalry Troop Only | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 37 | 60 | 43 | 60 |

| No Assets | 1.6 | 37 | 37 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Computation of VC Eliminated | 742 | 742 | 1213 | 1377 | 1530 | 1291 | 1318 | |

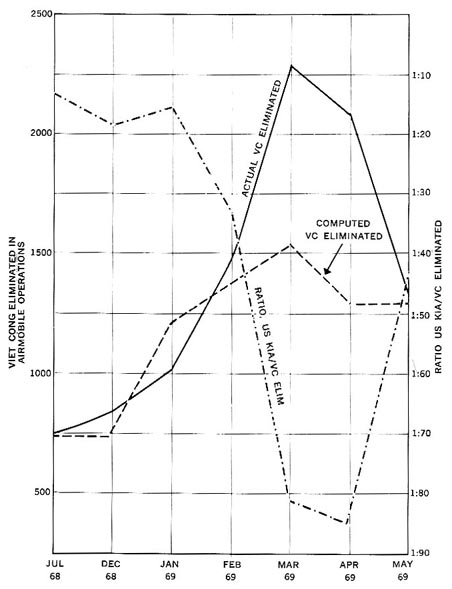

the addition of 1 Air Cavalry Troop and 1 Assault Helicopter Company. In the months of February and March we improved our aircraft availability so that we could fill the stand-down gap of the Air Cavalry Troops and Assault Helicopter Companies with organic aviation. Additionally, we were flying an average of 20 night missions per brigade. In April we lost an air cavalry troop and this began to have its effect on combat effectiveness. The Viet Cong eliminated shown in the total at the bottom of table 11 was computed by multiplying the brigade-days by the factors shown.

The actual Viet Cong eliminated per month in combat operations involving day cavalry, night cavalry, and day infantry is shown in table 12. These were the only type operations that were directly affected by aviation assets. The Sniper Program, night infantry, and artillery were not influenced to any appreciable degree by aviation assets.

Note that for the months of July 1968, December 1968, January 1969, and February 1969, the enemy losses computed were roughly the same as the actual enemy losses attributable to those operations utilizing aircraft. The exceptions were the sizable improvements

TABLE 12-ACTUAL VIET CONG ELIMINATED

| U.S. Units | Jul 68 | Dec 68 | Jan 69 | Feb 69 | Mar 69 | Apr 69 | May 69 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night Cavalry | - | 34 | 143 | 391 | 580 | 355 | 266 |

| Day Cavalry | - | 398 | 341 | 337 | 572 | 429 | 516 |

| Day Infantry | 735 | 396 | 539 | 726 | 1138 | 1293 | 1034 |

| TOTAL | 735 | 828 | 1023 | 1454 | 2290 | 2077 | 1816 |

[69]

over the calculated figure for the months of March and April 1969. In these two months everything jelled for the division. The Viet Cong apparatus became unglued and we capitalized on their shock at being taken apart both day and night. After two months of intensive nighttime operations the Viet Cong reacted and partially turned us off and we were never as effective as we were during the initial period of our stepped up night operations.

One might presume that with our improved tactical innovations and optimized flying hour utilization that there should have been a greater improvement in tactical success; yet, except for the exploitations in March and April, the increase in Viet Cong eliminated was directly proportional to the assets available.

But there was in fact a larger payoff. It came in the savings of American lives. (See Table 13 and Chart 6.)

While the enemy eliminated remained directly proportional to our aviation assets, Our exchange ratio-the ratio of enemy eliminated to U.S. killed-increased dramatically, reaching its peak also during March and April 1969 when the Division-wide ratio was over 80 to 1. This compares to a ratio of around 16 to 1 prior to honing our airmobile techniques. Although we were pleased with our increased efficiency in eliminating the enemy it was this dramatic reduction in the relative (and absolute) loss of our own personnel that was the most satisfying aspect of our improved utilization of aviation assets (and improved tactics) .

In the Spring of 1968 the three brigades of the division were located in the Delta area: the 3rd Brigade was located in Long An Province in the III Corps Tactical Zone, a very rich province south of Saigon; the 2d Brigade (Riverine Force) was located primarily aboard ship but was headquartered at Dong Tam with its primary focus toward Kien Hoa Province, IV Corps Tactical Zone, long a Viet Cong stronghold; and the 1st Brigade was located in Dinh Tuong Province, IV Corps Tactical Zone, with the job of keeping open Highway 4, the critical life line for food supplies between the delta and Saigon. On the other hand, the Division Headquarters with the majority of the Support Command and almost all of the

TABLE 13-COMBAT EFFICIENCY EXCHANGE RATIO OF TOTAL ENEMY ELIMINATED TO U.S. KILLED IN ACTION

| Jul 1968 | Dec 1968 | Jan 1969 | Feb 1969 | Mar 1969 | Apr 1969 | May 1969 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13.6:1 | 18.6:1 | 15.6:1 | 33.0:1 | 80.9:1 | 84.8:1 | 43.4:1 |

[70]

CHART 6-COMPARISON ACTUAL VS COMPUTED BASE PERIOD MARCH AUGUST 1968 VIETCONG ELIMINATED IN AIRMOBILE OPERATIONS DECEMBER 1968 THRU MAY 1969

aviation assets were located at Bearcat some 15 miles northeast of Saigon. This presented major difficulties. The overland supply route between Bearcat and Dong Tam took 5 to 6 hours since all vehicles were required to go through Saigon. Even by air it was a 45 minute helicopter flight. Thus our logistical and support op-

[71]

erations were very inefficient in that we were operating on anything but interior lines.

In the summer of 1966, long before the 9th Division arrived in Vietnam, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, became convinced of the need for a base camp to be established in the Mekong Delta to support tactical operations in order to deny the use of the area as an established refuge to the enemy.

Specific criteria with regard to site selection were established. The base camp had to be deep within Viet Cong territory to allow maximum disruption of enemy operations. The land, about 600 acres, had to be sparsely populated so as to be readily available to the United States with minimum resettlement. Ready access to the system of waterways, which are the Delta's major lines of communications, was required for planned' use by the Riverine Forces.

These criteria could not be met by existing areas, so it was decided to construct an adequate area by hydraulic fill utilizing pipeline dredges. The site chosen was a rice paddy located at the junction of the Kinh Xang Canal and the Song My Tho, 8 kilometers west of My Tho. The objectives of the dredging operation which commenced in August 1966 were to dredge a 54 acre turning basin capable of handling up to LST type naval craft and to provide hydraulic fill capable of elevating the 600 acre tract an average 2.8 meters. Both of these requirements were met by 29 November 1967 by which time 17 million cubic yards of fill had been dredged.

Actual construction of the cantonment area began in January 1967 concurrent with the construction of a 1500 foot stabilized earth landing strip. After Tet 1968, everything was accelerated so that by July 1968 there was enough construction available at Dong Tam to move the 9th Division Headquarters from Bearcat.

The move of the division from Bearcat to Dong Tam took place over a two month period. Each step was well planned, with sound programming techniques to insure that operations at both locations could be carried on without any loss of combat effectiveness. When the division closed at Dong Tam in July 1968, a new phase of operations was heralded. By October, when the heliport facilities were finished, we were able to operate almost completely from this centrally located base. No longer were the Assault Helicopter Companies and air cavalry units wasting approximately two hours a day flying to and from Bearcat in order to conduct combat operations in the delta. The construction of the port facilities enabled ammunition, petroleum and other supplies to be brought directly to the Division Support Command and 1st Logistical Command units supporting the division at Dong Tam. Army and Navy

[72]

DONG TAM BEFORE AND DONG TAM AFTER

logistical back-up in the same area enabled better communications and enhanced Riverine Operations. This relocation to Dong Tam, as much as anything else, enhanced the division's combat posture.

The port facilities initially consisting of the turning basin project, started in March 1967 and completed in December of the

[73]

same year, were expanded by 1969 to include a sheet pile seawall, a LST ramp, a LCU ramp, a pontoon barge finger pier, and storage facilities.

Equally as important as the port facilities was the construction of the huge helicopter facility which included 21,000 square yards of maintenance apron; 351,000 gallons of fuel storage with a 595 gallon pump feeding 24 refueling points, fully capable of handling two Assault Helicopter Companies at once; and 174 helicopter revetments sufficient to park two Assault Helicopter Companies and two Air Cavalry Troops. The most important aspect of the new heliport was the five large hangars which enabled our around the clock maintenance to be performed. Considering the 2700-hour 30-day Assault Helicopter Companies limitations imposed by higher headquarters, the move to Dong Tam resulted in an 18 percent increase in flying hours available for combat operations.

The 12,500-man Dong Tam cantonment area was officially completed on 15 June 1969. The total expenditure by Army and Navy construction agencies involved approximately $8,000,000. The majority of the vertical construction was done by the combat troops themselves who, during the period, expended 572,148 man hours to complete 1,005,600 square feet of buildings while at the same time carrying on extensive combat missions. The more complex buildings and storage facilities were constructed by Army Engineers who also installed a 6,000 kilowatt hardened power plant and distribution system, a 27,000 gallon per hour water purification plant and distribution system a protected Medical Unit Self-Contained Transportable (MUST) hospital facility and 13.5 miles of cement stabilized roadways.

The farsightedness of General Westmoreland, who personally decided to construct this base camp and helped choose the site as well as the name Dong Tam which means "Friendship" in Vietnamese, materially assisted the 9th Division in its efforts to help pacify the Upper Delta Region.

[74]

page updated 19 November 2002

Return to the Table of Contents