CHAPTER IV

General Background For Battlefield Analysis

We have mentioned earlier that analytical techniques are useful to sub-optimize elements of operations. For example, one cannot readily describe the major functions involved in planning and executing a daylight company reconnaissance. This would require pages of checklists and if done would probably result in a mechanical operation. However, one could idealize and simplify the actual contact and sub-optimize that particular sub-program. As one begins to move up the scale and improve an operation as large and complex as the operations of a reinforced division one has to concentrate on essentials or the effort becomes so diffused that progress is slow and erratic.

The rough rule we used was to concentrate on matters that improved operations, tactics, and intelligence and to let other matters go at their own speed. This concentration was pursued with considerable intensity. We also insisted on rapid results. If an area needed improvement we would quick fix it on the basis of available information and as our data and understanding increased kept recycling the operation and analysis until we were satisfied. This resulted in a rapid surge of improvement that was very encouraging. This was somewhat comparable to painting a moving train-instead of stabilizing a problem for analysis we would analyze it dynamically. The Operation Safe Step research program previously discussed was a good example in that we were able to compress several years of normal sequential experimentation and research into a period of months by means of multiple approaches and plowing partial knowledge back into the project.

This is a subtle process but most profitable when one gets the hang of it. It depends on focus and speed-which in our case meant emphasis on operations and tactics, pursuing them with intensity and in a timely manner.

Of course there is an ever present danger that the analytic approach may stifle innovation. It is inherently a structured approach which tends to keep thinking and alternatives within certain frameworks. One can only attempt to keep an open mind on the

[75]

one hand while closing in on the more specific problems through analysis.

This was what we attempted to do as we strove to increase our combat efficiency. We wanted to optimize our results by providing maximum security within our area of operations at the least cost in lives and equipment to the soldiers of the division. These efforts directed towards making our fighting men in the field as efficient as possible in the .performance of their missions depended upon our intelligence, tactics, combat operations, and pacification efforts.

As mentioned earlier, in the big unit period of the Vietnamese War (1965-1967) , the North Vietnamese (and to a lesser extent the Viet Cong) evidently felt that they could defeat United States and South Vietnamese units in face-to-face combat under favorable conditions. During this period, while it was not easy to bring the enemy to combat on our terms, it was a manageable problem. In mid- or late-1967, the Communists went to ground and began to rebuild their units for the Tet offensive. This resulted in "evasive" tactics by which the Communists devoted the bulk of their energies to avoiding contact, accepting combat only when cornered or when the odds looked extremely favorable. During this period the tactics which had worked well for U.S. units for several years became less effective. This "evasive" period appeared to end with the Tet attacks. However, it became apparent later on after Tet that the enemy had adopted a "high point" policy which called for weeks or months of "evasion" followed by a short "high point" of attacks. It became more and more evident that this enemy tactic or strategy called for a change in tactics by the friendly troops.

In January of 1968, orientation courses at Forts Benning, Sill, and Rucker still featured battalion-sized operations, clover leaf patrols,1 heavy firepower, digging in every night, large (10 to 20 ship) airmobile assaults, and so on. It was recognized that changes were due but there was no coherent doctrine nor overall concept for changing to a more delicate approach. Upon arrival in Vietnam in the Spring of 1968 we intuitively sensed that we should change our doctrine, but had no clear-cut idea of what to do. In February and March, the enemy was still trying to capitalize on the Tet attacks, so it was relatively easy to come to grips with him. There was another high point in May and June, but thereafter (south of Saigon at least) the enemy emphasized evasive tactics even more,

[76]

and it became most difficult to maintain contact with him. With this as a backdrop, the 9th Infantry Division went into the spring and summer of 1968 looking for a solution-how to bring the enemy to battle on our terms rather than on his terms. We were willing to try anything within the limits of common sense and sound military judgment.

If one studied the enemy situation pessimistically and realistically, one could theorize that it would take several years to defeat the enemy badly enough to render him unable to threaten the security of the Vietnamese people. This phenomenon was most apparent in the 9th Division area in Long An Province. Here, U.S. units had been weakening the enemy modestly for several years. During Tet of 1968, however, the enemy was able to attack the province capital. Although enemy losses were fairly high and the damage to the capital minimal, he still had the psychological advantage of having been able to mount an attack. In March and April of 1968 he avoided contact, rebuilt his units to some degree and in May put elements of four or five battalions into the Mini-Tet attacks on Saigon. His casualties were again quite heavy, and in late May and June he avoided contact again, controlled his losses, and started to rebuild. We obviously had a real problem-unless we could get hold of and damage the enemy, he would come out of hiding every six months or so and achieve some successes-hopefully only psychological but successes none the less.

The solution arrived at, which took months of trial-and-error experimentation, was to find, encircle, and heavily damage the enemy main force and provincial battalions. The enemy reacted by dispersing into company and platoon sized elements. These were then dealt with by lowering the scale of friendly operations to company and platoon size and attacking these small enemy units on a continuous basis. This dispersed style of combat led to frequent day and night engagements. By stressing light infantry tactics and techniques, it was possible to inflict heavy cumulative losses on these small enemy units with low friendly casualties. This favorable exchange ratio became more pronounced as the enemy lost experienced leaders. An unexpected by-product of the dispersed style and the constant pressure was that enemy units at all levels were weakened, thus reducing their ability to generate replacements from local guerrilla units. As a result of the constant heavy military pressure, rallier (Chieu Hoi) rates also skyrocketed-thus further weakening the enemy forces. As the pacification program advanced, the Com-

[77]

munists progressively lost control of the people. South Vietnamese territorial forces also became more aggressive. The cumulative effect of all these interacting defeats was that the enemy lost strength and combat effectiveness geometrically rather than arithmetically.

All of the above sounds very simple but was achieved only by a concerted application of hard work, professional skill, tight management, lots of guts, and some luck. It took from six to nine months of tight management to get the infantry companies in top fighting shape. Optimum utilization of aviation assets required about six months to develop. Aggressive and effective small unit operations required two months of on-the-job retraining and so on. The two major breakthroughs were the result of sheer professional artistry. The rapid breaking down of the enemy battalions was the result of the perfection of both the jitterbug and the seal-and-pile-on technique (the rapid build-up of combat power to surround and destroy an enemy force) by Colonel Henry E. "Hank" Emerson. These highly complex tactics, in the hands of a master, shattered many large enemy units. The effective use of aggressive small unit operations was demonstrated as feasible by Captain Michael Peck Jr., an infantry company commander. By capitalizing on his example, we were able to break the enemy companies down. Thereafter, by close observation and analysis of results, we were able to vary our tactics and techniques and continue to put heavy pressure on the enemy.

When one first observes the fighting in Vietnam, there is a tendency to assume that the current tactics are about right and that previous tactics were rather uninspired if not wrong. The first conclusion is probably correct, the second is probably wrong. For example, one hears much criticism of the Search and Destroy Operations which were extensively used in 1967 and before. However, if one looks at the situation then existing and what was actually done, the tactics were pretty well chosen and did the job. Any reasonably effective commander, after observing the enemy operate a while, can cope with him reasonably well. The difficult task was to decide how the enemy was going to change his operations, to anticipate his change, and then keep driving him down, and thereby preserve the initiative. This requires very clear thinking, some risk-taking, and a flexible approach.

Our experience in the 9th Division illustrates the process well. When our units were first introduced into the delta, the practice (for a variety of sound reasons) was to make strong battalion or

[78]

multi-battalion sweeps followed by periods of lower level friendly activity. The enemy was pretty cocky and would attempt to block these sweeps into his long-time base areas and suffered heavy losses in the process. By the spring of 1968, he had decided to evade such sweeps whenever possible and as a result became more difficult to bring to battle. However, by a process of vigorous reconnaissance through both jitterbugging and ground patrolling, we were able to find these evading units, encircle them, and deal them very damaging blows.

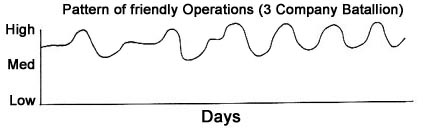

While the division was spread out over a large area and largely made up of three company battalions, each encirclement required a peaking of effort (with all available companies committed) followed by a stand-down period to rest and refit. This allowed the enemy to regroup somewhat, and his losses were damaging but manageable from his viewpoint. To put it differently, while his losses in trained personnel were damaging, he was able to replace a sizable proportion of his losses with new recruits. On the other hand, as he dispersed his units, his command and control mechanism was reduced in efficiency, and resupply became more difficult.

When the division reached its full strength, it was possible to put the pressure on the enemy continuously and conduct small encirclements with troops on hand. This resulted in many small contacts and a constant drain on the enemy, both in quality and quantity with which he could not cope. The loss of leaders was particu-

ENCIRCLEMENT

[79]

larly crippling. Eventually, the enemy became so disorganized that small friendly units could just overrun the enemy and encirclements were no longer necessary. [For some unknown reason, enemy artillery (mortar) units were much more difficult to neutralize than the infantry.]

This process sounds rather mechanical; however, the decision to break down to company and platoon level operations took real courage. One ran the risk of having a company overrun occasionally by an enemy battalion. However, luckily for us, by the time the enemy realized what was happening to him, he had been too badly damaged to do anything but break down further into platoons and ultimately into squads.

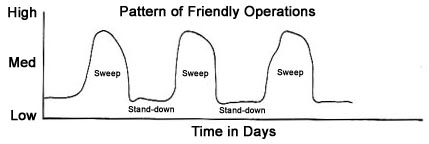

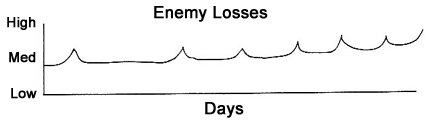

CHART 7-PATTERN OF ENEMY LOSSES RESULTING FROM SWEEPS

| Amount of Friendly Offensive Effort |

|

| Enemy Losses |

|

| Enemy Losses |

|

[80]

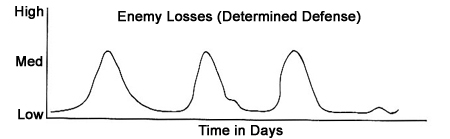

This process is graphically portrayed in Charts 7 and 8. The first chart indicates the friendly offensive effort associated with large sweeps. Because of the large numbers of troops participating in a sweep, there were periods of intense activity followed by prolonged stand-down periods. If during a sweep the enemy chose to stand and fight, his losses could be high. Naturally enemy losses would fall off during the periods of stand-down. If the enemy chose to evade, he

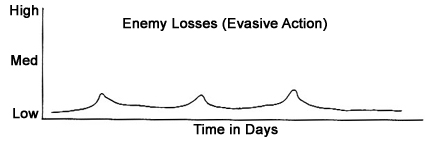

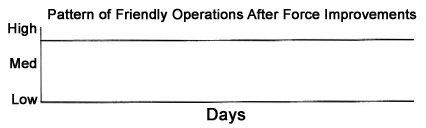

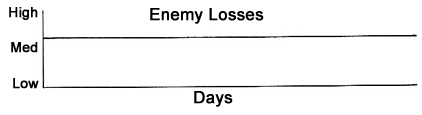

CHART 8-PATTERN OF ENEMY LOSSES RESULTING FROM RECONNAISSANCE MODE

| Friendly Offensive Effort |

|

| Enemy Losses |

|

| Friendly Offensive Effort |

|

| Enemy Losses |

|

[81]

normally could side-step large unit operations and his losses even at the peak of the sweep would not be very high. On the other hand, when we went to the reconnaissance mode of operations (Chart 8) , covering large areas on a daily basis, friendly offensive efforts were generally maintained at a medium intensity, although from time to time in an encirclement the level of activity peaked. The enemy's losses were also about medium level. As we refined our tactical operations, fighting night and day, and gained our full strength through force improvements, the level of friendly offensive effort became constantly high with few perturbations. As a consequence, the level of the enemy losses went even higher and they were constant, damaging the enemy so rapidly that his units deteriorated steadily and could not recover.

The Theoretical Basis of the Constant Pressure Concept

The Constant Pressure Concept paid off in cold results; however, in retrospect, its real strength was that it largely disrupted a Communist concept of operations which had proven successful since the early days of the Indochinese War.

The classic method of operating for a Communist unit (North Vietnamese Army or Viet Cong) was to take refuge in a relatively secure base area and spend some weeks reorganizing, retraining, and replacing losses of men, materiel and supplies. During this period, it would carefully plan a set-piece attack on a government unit or objective and then execute the attack with the actual movement to the attack, the attack itself, and the withdrawal taking place in a short period of three or four nights or less. If the attack, due to this careful preparation or other reasons, was reasonably successful, the government strength and confidence dropped and the more confident enemy recycled the whole procedure.

With the Constant Pressure Concept, friendly units upset this enemy timetable. By means of constant reconnaissance, small engagements with enemy units and pressure on their bases, the Communists were no longer able to rest 25 days a month; they could not refit and retrain and eventually could not even plan new attacks very well, much less execute them.

This process is very difficult to measure in any finite way. However, as a rough estimate, if the friendly forces (all types) in an area can diminish the enemy about 5 percent a month and achieve a friendly-initiated to enemy-initiated contact ratio of 3 to 1, the friendlies have the initiative and the enemy slowly goes down hill. In this situation, pacification proceeds and compounds the enemy's difficulties by separating him from the people who had previously

[82]

helped him (willingly or unwillingly) by furnishing recruits, food, labor, information, etc.

The best performance ever seen to my knowledge was in Long An Province where in 1969 and 1970 the friendly forces were able, months on end, to weaken the enemy about 10 to 15 percent a month and achieve a contact ratio of about 6 to 1. This paralyzed and eventually almost disintegrated the enemy, even though the Cambodian sanctuaries were nearby. This military pressure, coupled with a dynamic and most effective pacification program led by Colonel Le Van Tu, a superb province chief, brought Long An from a highly contested to a relatively pacified area in about two years. This was the perfect strategy-excruciating direct military pressure coupled with strong pacification hitting the enemy from the rear. The Cambodian operation, by denying the enemy a secure base, was the coup de grace.

Thus, by adopting tactics which not only bled the enemy, but worked against his classic method of operating, one could make impressive gains. This approach, while very obvious in retrospect, was not clearly seen at the time and was arrived at by trial and error. It required a high degree of tactical skill by the regular units (U.S. or South Vietnamese). When coupled with a substantial increase in Regional Force and Popular Force units to maintain reasonable and continuous local territorial control and security, the Communists steadily lost ground.

In all fairness it should be admitted that we rather backed into this solution. Prior to our beginning to keep detailed statistics on combat results, we thought that our larger engagements were the payoff and the smaller just a bonus. However, as one observed the statistics closely, it became apparent that the aggregate results from small contacts were quite important. Once we began to stress small unit operations, it was established that the great majority of the enemy losses (80 percent to 90 percent) came in very small contacts with medium or large contacts amounting to a smaller percentage (20 percent to 10 percent). We then began to realize that the supermarket approach of large turnover with small unit profit paid off much more than the old neighborhood grocery approach of small turnover with a large markup. This particular solution was even more necessary in the upper delta than might have been the case elsewhere, as the enemy was constantly in motion over the open terrain rather than hidden in large jungle-covered secret base areas. This made constant pressure a necessity.

It is interesting to observe the South Vietnamese experience by way of contrast. The South Vietnamese were rather cautious (with

[83]

good reason-they and the Viet Cong had historically taken turns decimating a battalion or two every six months or so). They planned big multi-battalion sweeps and coordinated them with all agencies. As a result the Viet Cong not only had general knowledge of their plans due to leaks, but the tactical plan was usually a highly stylized attack of the French staff school variety. As a result the Viet Cong could usually sidestep the operation. (We sometimes obtained moderate returns by sending units along the edges of a South Vietnamese operation to pick up the evading Viet Cong units.) We avoided similar security problems by obtaining large operational areas for periods of time and telling no one what we had in mind. Once a South Vietnamese unit changed to a looser style and minimized leaks, its effectiveness rose perceptibly.

A more fundamental reason for the success of the Constant Pressure Concept plus pacification was that it upset the entire Maoist method of organizing the "masses" and if done well over time forced them to reverse the traditional Maoist three phase concept.

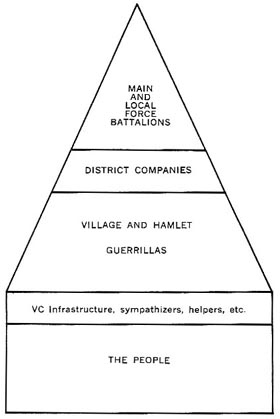

If one looks at Chart 9 of the Communist structure, one can visualize the way in which the Viet Cong made the people (the so-called masses) support the bulk of the war effort. The people were forced to do all the work, furnish the food, intelligence, labor, and the raw recruits. Each Communist level supported the one above, and if a lower level unit such as a district company was in trouble, a larger and higher level unit was brought in to rectify the situation.

Historically, after 1954, the Communists organized the people, went into guerrilla war, and in 1964 and 1965 went into the open warfare stage and with North Vietnamese help were making real progress until U.S. units were introduced and began regularly to defeat the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army main forces. In an effort to stop this series of defeats, the enemy attacked the cities in Tet of 1968. The Tet battles were supported in many areas by drawing heavily on the lower levels for replacements for main force units. The heavy losses incurred seriously weakened the underlying structure.

By using the Constant Pressure Concept to inflict losses throughout this weakened structure, Communist ability to upgrade units and personnel was hampered. The heavy military pressure generated hundreds of ralliers (Chieu Hoi) who primarily came from the linking layers of local (village and hamlet) guerrillas and sympathizers and helpers. The linking mechanism then began to fray. As the pacification program went into high gear (in 1969) and provided more constant local security, the people in general were

[84]

CHART 9-THE COMMUNIST STRUCTURE

able to draw away from the Viet Cong or in the case of traditional Communist areas were prevented from helping them. This was a drastic shift from the Communist point of view. Whereas previously the Communist units only rested, trained and fought, they now had to support themselves. This resulted in a serious drop in their combat capability. If military pressure was heavy and pacification dynamic at the same time, the enemy structure underwent a collapsing effect. If the pressure was maintained for a year or two, the structure almost disintegrated. It took considerable skill and patience to bring this development about.

The first sign of enemy trouble was the introduction of North Vietnamese Army fillers into Viet Cong battalions; large numbers of ralliers was another sign of trouble, friendly pacification progress another, and rapid erosion of all units was a very bad sign. Central Office of South Vietnam Resolution Number 9 which stressed a

[85]

return to low-level operations (terror, anti-pacification, etc.) was the formal admission by the North Vietnamese High Command that they were in real trouble, as it reversed the Maoist doctrine.

Many Westerners cannot understand why the South Vienamese situation should have been greatly different in 1970 than in 1967 or 1968. However, if one assumes that the Communists controlled half the rural population, no matter how imperfectly, in 1967 and the South Vietnamese government, which was just organizing, to some extent controlled the other half-we can see that the power balance in the rural areas was fairly even. In 1970 the Communists were in some disarray and had lost control of most of the rural population. The government had made considerable strides, had gone to general mobilization, and controlled most of the rural people plus the cities reasonably well. As a result the government was some millions of people stronger and the enemy the same number weaker.

In summary, the Constant Pressure Concept while inflicting heavy damage on the enemy struck directly at the basic Communist concept of operation and at their method of organizing their entire apparatus. It thus caused many problems for the Communists when well executed.

Increasing Emphasis on Offensive Operations

It is, of course, a military truism that offensive operations are more effective than defensive operations. However, this principle was somewhat blurred during the earlier years of the Vietnamese war by the willingness of the enemy, particularly the North Vietnamese, to try to overrun fire support bases, thereby losing several hundred men in a few hours. In the delta area, however, the enemy was less prone to attack fortified positions (particularly U.S. ones) , so this situation did not exist to the same extent.

After some informal checking around, it was found that the general pattern in late 1967 to early 1968 was that offensive operations produced modest results and defensive operations little, except for an occasional defense of a fire support base against a strong attack. After some thought and analysis, a very simple report was devised which allowed the division and brigade commanders to keep a running account of the number of company days and nights of effort on offensive and defensive operations. This report confirmed that about one-half or more of the combat troops in the division were on security, stand-down, training, or other missions which did not contribute positively to finding and defeating the enemy.

[86]

KEEPING THE PRESSURE ON

[87]

The night percentages of defensive effort were even higher. These results were quite understandable since the average unit was assigned, either directly or indirectly, a number of missions such as find-and-attack the enemy, guard a bridge, secure a road, protect a fire support base, rest tired troops, perform training, etc. There was a tendency to assign a reasonable force to each defensive mission to lessen the risk. As a result, the offensive missions got what was left, unless a big operation was underway. The tendency towards defensive effort was even more marked at night due to the proclivity of the Communists for night attacks. By lumping all of the missions together in a continuing report, the degradation of offensive effort became more apparent and all commanders and staffs began to work to optimize the offensive effort. Correcting this defensive tendency required deliberate defensive risks in order to increase offensive effort. An attainable goal (and floor) of 60 percent of all units committed to offensive operations was set. Units tended to float between 60 percent plus and 75 percent-66 percent being a reasonable average figure for offensive operations. After several months, this control measure was not really necessary for daytime operations but was retained to impress the concept on new commanders and to permit the night rate to be observed. The night offensive rate took much longer to bring up.

Some people thought this approach was so basic as to be ridiculous, however the technique was adopted by a division which had too few men committed to offensive operations and was having extreme difficulty in finding the enemy. At first, the division offensive rate was between 40 and 50 percent; after corrective action it rose to over 66 percent. In more concrete terms, it had previously averaged about 17 companies per day on offense and rose to about 26-an increase of 50 percent in offensive effort from the same force. Obviously, this change alone did not necessarily solve its problems but it helped.

The end result was that the rifle companies of the 9th Division spent approximately two-thirds of their time in the field on offensive operations. Everything else-security, rest, care and maintenance of equipment, training, etc.-came out of the remaining one-third. This kept the men very busy but still allowed them sufficient rest to be fresh for operations. It must be admitted that we could not confirm that this measure in itself led to better results. However, the principle involved was obviously so sound that it was retained to point us in the right direction.

[88]

In the spring of 1968 in Dinh Tuong Province, one of the companies was commanded by Captain Peck-a superb small unit tactician and leader. As he began to fragment, and the enemy battalions and contacts were more difficult to come by, he-mainly on his own initiative-started aggressive company and platoon sized operations with dramatic results. Not only did he terrorize the enemy and deal them heavy casualties, but his own casualties were quite light.

This suggested the need to expand such techniques and the results were promising. Occasionally, a company or platoon was roughly handled, but as we developed more skill and the enemy's skill level dropped, we were able to employ aggressive or even audacious small unit operations with almost total success.

By March of 1969 we never, or almost never, used battalion level sweeps or encirclements but used company or platoon level operations. This, of course, multiplied our coverage of the ground, our reconnaissance effort, and our contact possibilities by an order of magnitude of roughly 3 (1 battalion equals 3 companies on offen-

FIREFIGHT

[89]

sive effort) . In addition, the enemy seemed unable to figure out this dispersed style of operations and he was never able to cope with it. If he concentrated to strike a company, we encircled him; if he dispersed, the platoons overran the small enemy elements.

Obviously, this approach was very sensitive to the level of tactical skill, and we soon found that some platoon leaders or company commanders did not do well with it. By a combination of observation and analysis, we found that the utilization of artillery was critical. The Standing Operating Procedure approach for developing a contact was to bring in artillery fire and then start a flanking maneuver. This resulted in a five to ten minute delay during which time the enemy was able to slip away. We finally hit on the idea of starting the maneuver at once (battle drill style) and then bringing in the artillery, if necessary. This very simple fix was most effective. It, in effect, reduced the enemy's escape time from five to ten minutes to two to five minutes, which was not enough for his purposes.

It was customary in Vietnam, particularly in the jungle, to stop moving in mid or late afternoon, resupply, and dig in a hastily fortified position. We noted relatively few night attacks in the delta, and it was almost impossible to dig in due to the high water table, so we changed. We either did not resupply or did it in late afternoon, kept going until dark, and shifted to night ambushes after dark. This simple trick eliminated enemy night mortar attacks and almost all night attacks. In a few tough areas, it did not work quite as well until we guessed the enemy was tailing our units. After we made sure to shake or kill the tails by stay-behind ambushes, this .stopped.

It was apparent that an infantryman in the delta mud and heat suffered terribly from both heat and fatigue. The flak jacket was a primary cause. After analyzing wound data and flak jacket saves, we determined we were not saving many casualties by their use and, as a result, made the wearing of flak jackets optional. Some experts felt that the gain in mobility paid off in better results with few consequent casualties although this was never clearly established. Even in heavily booby-trapped areas, one could get by with using jackets on lead men only. By rotating lead men, the fatigue element could be held down. We did not direct the abandonment of flak jackets, however, as some people derived considerable

[90]

psychological assurance from them. Due to the fact that our men were only out two days and could usually be resupplied easily, we also reduced the individual load to a bare minimum by reducing ammunition loads and other paraphenalia. The theory was to get the men to the battle fresh. Perhaps not all individual riflemen would agree.

LOAD OF THE SOLDIER

[91]

We also reduced the unit loads somewhat. Due to the muddy delta terrain, the heavier crew-served weapons were very difficult to utilize and actually were not really necessary as artillery support was almost always available. Eventually, we did away almost entirely with 4.2-inch (107-mm) mortars and 81-mm mortars. This made the foot elements more mobile and freed heavy weapons men for other missions-usually as members of a reconnaissance unit.

It has been customary in Vietnam for some time to deliver heavy preparatory fires on the vegetation cover around a landing zone in order to reduce the amount of enemy fire at the choppers and at the troops. This practice was essential in some places, desirable in others, and questionable elsewhere. The preparation might involve gunships, tactical air, and artillery and took from five to fifteen minutes, depending on the amount considered necessary and the complexity of the fire plan. As our contacts began to drop in 1967 and 1968, we examined this practice critically. We finally judged that the enemy had very few .50 caliber machine guns in any case and intuitively guessed that the time used for the "prep" was alerting the enemy and allowing him to evade. So we cautiously experimented with airmobile operations without using preps. After finding we received very little fire, we changed the Standing Operating Procedure 180°. No preps were used unless the commander felt the situation demanded it. This worked well-we had to go back to standard preps only in one place-a very tough area where we had one whole lift shot up due to a sloppy light prep. Not only did the no-prep policy increase our element of surprise, but it saved artillery ammunition, air strikes, and gunships for more lucrative targets. The biggest bonus was to relieve the air cavalry gunships so they could work with their parent troop. The lift ship gunships initially overwatched the insertion so they could intervene if necessary. After some weeks, we noticed that the enemy was "leaking" out of the area as soon as the lift ships began to land. We then shifted the gunships to watch the outside rather than the inside of the insertion area. This not only cost the enemy casualties, but held them in place. As a result we had, over a period of months, essentially turned the landing zone preparation around.

The original approach in open delta terrain had been to land our assault helicopter lifts 600 to 1,000 meters from the objective

[92]

in order to minimize the effect of direct fire on aircraft and infantry. This meant that it took the troops an appreciable time and physical effort to make their way through the rice paddies to the objective. After observing the low incidence of enemy .50 caliber machine guns, we cut the distance to 500 to 600 meters and observed no problems. After a few weeks, we reduced it to 300 meters (based on effective rifle fire and light machine gun range) and had few problems. This reduced the approach march time by two-thirds to one-half and increased surprise. By the combination of eliminating preps and reducing the standoff distance, we increased surprise and lessened troop fatigue.

Later on in 1969 the 3d Brigade of the 9th Division in Long An reduced their standoff distance to as little as 15 meters. The enemy by that time had little but AK-47 rifles to work with. This short distance was ideal, as surprise was almost total and only one or two enemy could fire at a particular chopper. Usually, they elected to hide instead.

Why did it take us so long to decide on variations that were obviously such good ideas? The situation was not crystal clear at the time. To begin with, the previous Standing Operating Procedure

(liberal prepping and substantial stand off distance) was adopted during a period when the enemy response to an airmobile assault was a withering hail of fire from all weapons, and a vigorous defense until nightfall, when he made good his escape. When the enemy changed to evasive tactics, he began to lie doggo and try to avoid contact with a view to escaping in daylight or at night depending on the amount of concealment available. If the friendly unit made contact, the enemy opened fire at very close ranges (perhaps 15 feet) which usually led to a costly, difficult, and time-consuming organization of an attack from a different direction. An examination of exchange ratios during the spring and summer of 1968, ratios which were around 10 to 1, shows that we were having difficulty with these enemy tactics. If one drove head on into a heavily bunkered position, friendly casualties were high; and if one maneuvered, the enemy slipped away. Fortunately, at this juncture, the jitterbug technique, which had a high success rate in finding enemy units, and the seal and pile-on tactic which prevented escape and inflicted crippling losses on enemy units were perfected. The overall result was that the enemy units began to fragment. At that point, the changes in landing zone prepping and insertion distance began to be more advantageous and paid off in increased enemy elimina-

[93]

tions and higher exchange ratios. So, as we have stated earlier, the solution to a tactical problem was not necessarily simple or straightforward.

One difficulty encountered in analyzing such complex operations was that one did not understand the critical points involved. The whole desired effect of changing the prepping and standoff Standing Operating Procedures was to increase surprise and consequently the closure rate. If one assumed that the total closure time was sixty minutes originally and was able to reduce it to thirty minutes-nothing in particular happened. What was overlooked was that the enemy only needed an escape envelope of ten to fifteen minutes. Its was not until we achieved the technical skill and took the risks to effect lightning fast frontal attacks that the critical envelope was penetrated and the success ratio climbed to high levels. There were many other factors involved, discussion of which must be omitted due to length.

The foregoing general discussion gives you some feel of the problems faced, some of the solutions, and our thinking behind these actions. To summarize succinctly the 9th Division evolved differing tactics and techniques which basically involved the theory of constant pressure through offensive actions using small units operating night and day.

The key to ground tactical success was breaking down into small unit operations, particularly at night. We passed on this formula to, the 7th ARVN Division which operated with us in the delta. It proved at that time to be a shot in the arm for their combat efficiency also although they were more reluctant to break down into small units because of some bitter experiences earlier in the war. Finally, the key to all of our tactical success was good intelligence, without which even the most refined techniques would have been substantially less productive.

In all of our operations we applied as best we could the analytical approach to our problems. The technique employed was to isolate those pieces of the problem which could be analyzed. The remainder had to be attacked primarily by means of professional skill, experience, judgment and often intuition. The overall integration always had to be done on this basis. Even in areas such as small unit techniques which on the surface responded well to analysis, the actual cause and effect relationships could not be traced with any real confidence. However, as has been mentioned earlier, the Vietnamese War was, and is rather complex, murky, and difficult to under-

[94]

stand. It should also be recognized that many aspects of the war are too complex to be susceptible to operations analysis. Field force, division, brigade and battalion operations, for example, are just too complex to completely comprehend by analytical methods. These comments should not discourage attempts to improve operations by analysis or otherwise; we merely make the obvious point that the human mind can grasp large problems by some means which are difficult or impossible to duplicate on paper.

Straightforward collection of statistics has its pitfalls also. This approach leads toward optimizing the operation being studied. While this is obviously desirable as a rule, it may tend to stifle innovation and unconventional thinking. For example, one good way to improve the effectiveness of daylight operations is to improve night operations. The theory is that the enemy is thereby forced to operate more frequently in the daytime. However, this cannot be proven. In defending against booby traps one rapidly gets up in the flat portion of the learning curve. A good way to finesse the problem was to rely heavily on night ambushes. The overall outcome was better results with less booby trap casualties. However, this alternative obviously did not stem from a close analysis of the bobby trap problem. A similar turn around of interest was the reversal of roles of airmobile operations and ground operations. In mid 1968 the jitterbug (intensive small unit airmobile reconnaissance) was driving daylight operations with ground patrolling a poor second. However, by early 1969, ground patrolling became more and more important and the jitterbug less so. Similarly, the air cavalry role switched from one of finding targets for the jitterbug to that of attacking targets flushed out by the ground patrols. It is theorized that the jitterbug became so feared that the enemy would never break cover unless physically contacted whereas the ground patrol was so unexpected (and more thorough) that he could not accommodate to it.

To give a better insight into our approaches to improving operational efficiency through analysis, we will subsequently discuss several of our fundamental building blocks, i.e., intelligence, tactical innovations and operational reviews.

[95]

Endnotes for Chapter IV

1 A type of patrol used in jungle growth which featured a clover leaf pattern for searching out the enemy and ensuring thorough coverage of the terrain. (click here to go back)

page updated 19 November 2002

Return to the Table of Contents