CHAPTER VIII

Pacification

As mentioned previously, we attempted to integrate combat operations and pacification efforts in all of our planning. To do this the G-2, G-3 and G-5 worked as a well-oiled team, sharing the same space in the tactical operations center and coordinating their operations. To insure the pragmatic integration of intelligence, operations and civic action we hand picked two outstanding combat leaders to be G-5's-Lieutenant Colonel Tom Leggett and Major Bernard O. Loeffke. Our coordination paid off-there is no doubt that by keeping great pressure on the enemy we enhanced the security of the countryside thereby facilitating the pacification mission.

Our pacification efforts were well thought out and integrated as much as possible with combat operations. In addition, our pacification program had as its foundation five major civic action themes: (1) psychological operations or efforts to win the hearts and minds of the dissident people so that they would rally to the side of the Government of Vietnam, (2) assistance to the victims of the war, (3) assistance in health matters, (4) educational assistance, and (5) the repair and construction of facilities. In each of these approaches we attempted to innovate and improve our techniques in order to bring imaginative and worthwhile programs to the people of Vietnam.

It is not our intention to go into pacification in any detail. It is a whole subject in itself. Pacification became most important about July 1968 and although the efforts of the 9th Division in the subsequent years were innovative and rather broad gauge, they were not as concentrated nor as important as later efforts. Therefore, we will list only a few of our efforts in each of the aforementioned areas to provide an insight into pacification and to indicate how these efforts often tied directly into combat operations.

Psychological operations pervaded the total quiltwork of the war. They were necessary to break down the fabric of resistance of

[164]

the active enemy forces as well as to encourage the villagers and others to return to the Government fold.

We urged the enemy to surrender or to rally to the side of the Government of Vietnam rather than face eventual death. We took every opportunity available through leaflets, loud speakers, and face to face contacts to induce him to give up his hopeless cause, and to rally to a more democratic and hopeful way of life.

We also tried to reach the hearts and minds of the people who had been subjected to much Communist propaganda. To do this we employed every available means of psychological warfare available to us. Psychological warfare, then, had two different aspects-destruction of the enemy's will to fight and the winning of the confidence of the civilian populace.

Prior to our arrival in Vietnam we set about procuring 100 handheld loud speakers (AN-PIQ 5A) in hopes that the tactical situation would permit our talking major Viet Cong units into surrendering. While still in the States we even had cards made in English and Vietnamese so that our Tiger Scouts could coax the enemy out of his positions. The emphasis of the 9th Division

BREAKING THE LANGUAGE BARRIER

[165]

throughout the war had been primarily on obtaining Chieu Hois and Prisoners of War and secondarily on killing the enemy. We wanted the total enemy eliminated to be as high as possible, hopefully by taking as many prisoners as we could. The reasons for this, of course, are readily apparent. In combat operations Prisoners of War and Chieu Hois give a great amount of military intelligence. Chieu Hois can also be used to talk others into surrendering. One of the most valuable assets of the 9th Division in this connection were our Tiger Scouts. We assigned at least one Tiger Scout to each infantry platoon and later each squad. Because they were familiar with Viet Cong thinking and operations they often anticipated his moves, thereby giving us tactical advantages. They also afforded an important psychological and actual link to the civilian population. Most Tiger Scouts were intensely loyal to their American unit-there is nothing like a convert. Their conversion to the Government of Vietnam side was an obvious example to their countrymen.

We have previously described how during our "seal operations" we would fly aerial loud speaker missions to talk the enemy into surrendering. Once the seal was closed the enemy was heavily bombarded with artillery and air strikes. Subsequently, we would have a hiatus for the purpose of talking the enemy into surrendering. However, our aspirations were much greater than our results. For example, one day in Long An along the Vam Co Tay we succeeded in talking a Viet Cong soldier into surrendering during the middle of battle. He came out with his hands up and progressed no further than 30 meters from his bunker when he was shot in the back by one of his comrades. This so infuriated our troops that they laid down a withering suppressive fire and two of our soldiers rescued the hapless Viet Cong. He was evacuated and we managed to save his life. The thought is, that as long as there were a few hard core Communists in a unit it was difficult for any of the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese to rally.

Our psychological operations campaign against enemy units was relentless. After every major battle we dropped leaflets depicting their casualties by showing gravestones whose headings included the enemy unit's losses from previous battles. We sent messages over local radio stations to the effect that the Viet Cong should Chieu Hoi or they would be killed. We flew airborne loud speaker missions whose purpose was to spread dissension and unrest in the enemy ranks as they spent lonely, uncomfortable periods deep in the hot, humid and mosquito infested base camp areas. They hated these loud speaker missions so much that rather than listen to any

[166]

more propaganda they would stand up and fire their weapons at the loudspeaker aircraft thus exposing themselves and their positions. We dropped millions of leaflets over Viet Cong positions inviting the enemy to rally to the Government of Vietnam. (One of our staff officers briefed one night that if all the leaflets dropped in the past three years in our tactical area of operational interest remained on the ground we would all be up to our "waists" in leaflets instead of water.) Many thought leaflets had no effect. That was not our experience. On one occasion we promised the enemy a hot meal and a hot bath if he would rally. One night a Chieu Hoi raised the dickens because he had not yet had his hot bath as promised by the leaflets.

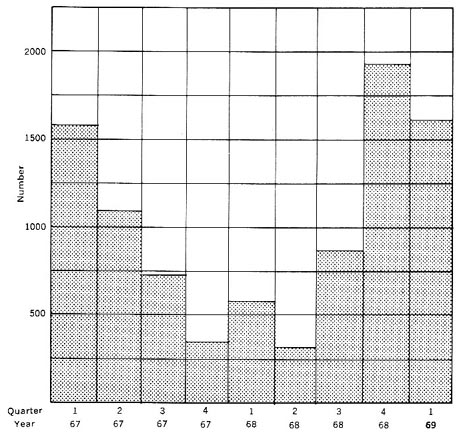

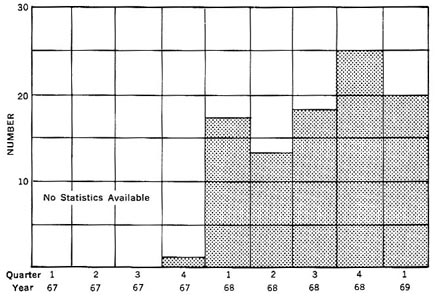

Yet, no matter how hard we tried we did not appreciably increase the number of enemy rallying to our troops. The language barrier was too much. However, within our tactical area of operational interest as the pressure got hotter the number of ralliers (Chieu Hoi) to Government of Vietnam authorities increased greatly. (Chart 15) Since our interest lay in the totality of operations our own lack of results didn't matter too much.

Propaganda was not a one-way street. The Viet Cong had their campaigns too. By analyzing their themes we learned the "big impact ideas" and reversed the procedure with the Viet Cong as the targets. Their efforts were not as sophisticated as many would have you think, as evidenced by the leaflet partially reproduced below.

VC Propaganda Leaflet

(partial)

American officers and men in the US armed forces in SVN:

In Viet Nam lunar new year is old traditional custoon and Habit.

The Vietnamese people desire for a peaceful and external for an

enjoyment, in new year days in the happy atmosphere of their family reunion and

for the holding of a mom oriental ceremony to commen-orate their ancestors, is

stronger than that of anybody else it is the same as the american people enjoy

their merry xmas and happy solar new year in their sweet home beside their loved

ones. The US warmongers and their Thieu Ky Huong puppt chique however don't want

peace they not only sabotaged the SVNLF orde concoriving the suspen-riou of all

military attack derring a recent xmas but also rejected openly to implement the

fronts solar new year truce order in the war future they will seek all means

avuitable to sabotage the coming lunar new year truce by pushing you out on

operation causing suffering mourning and hare hip to our people.

American serira men!

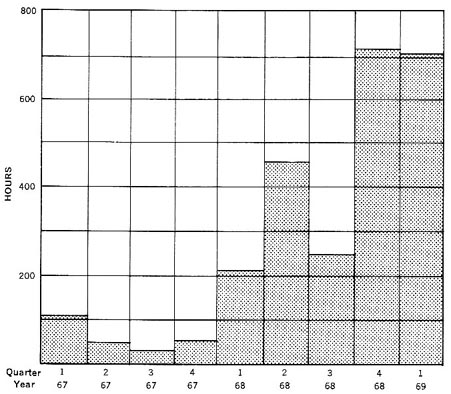

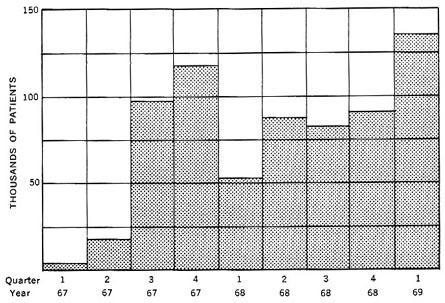

Winning the confidence of the civilian populace took integrated efforts in many areas. We broadcast literally thousands of ground loudspeaker hours (Chart 16) in support of pacification. However,

[167]

CHART 15-NUMBER OF CHIEU HOIS IN 9TH DIVISION TACTICAL AREA

Rate for 9th Dv Tactical Area of Operational Interest Total 8949 Chieu Hois

face to face actions were more effective than airborne measures. We distributed almost two million hand-delivered leaflets through our Medical Civic Action Programs. We established games to play with the children of villages. We raffled off chickens and ducks. We gave away thousands of children's T-shirts in the colors of the Government of Vietnam. We produced cards to be passed out telling why the Americans were there. We taught our soldiers the customs of the Vietnamese so that they would not offend the local population. We went to extraordinary means to assure the Vietnamese that we were there solely to support their Government and to make a better way of life for them. The visits by U.S. medical teams with their friendly attitudes and accompanying entertainment were

[168]

CHART 16-GROUND LOUDSPEAKER HOURS

These hours are in support of the civil action program in a face to face

psychological operations effort. They do not include aerial loudspeaker time. Total time 2580 hours

events to be anticipated and remembered by many. Because of the language difficulties our attempts to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese were not as polished nor as fruitful as we would have liked. But in trying to reach their hearts we showed that our hearts were in the right place.

Assistance to the Victims of the War

The individual American soldier has always helped to alleviate the suffering and anguish caused by wars, and Vietnam was no exception. The 9th Division soldier was quick to volunteer with both labor and monetary contributions. We tried as much as possible to initiate cooperative programs whose objectives were to provide

[169]

CHRISTMAS WITH THE ORPHANS

assets to the Vietnamese so that they could help themselves. But the most important of all contributions was the individual soldier's willingness to assist in any manner practicable to lessen the Vietnamese citizen's plight. Orphanages, churches, leper colonies and the physically handicapped all received his warm support.

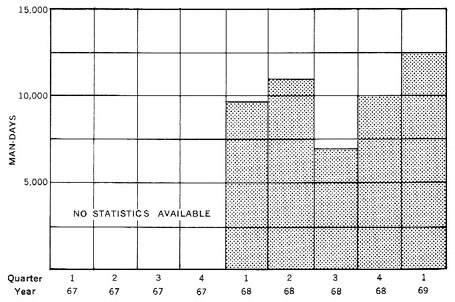

The giving of one's own time and effort is often more meaningful than gifts of money and material. As our Civic Action Programs became more organized the soldier man-days spent increased greatly so that we had on the average of 150 men daily working on construction activities, Medical Civic Action Programs and staff work in support of pacification. (Chart 17)

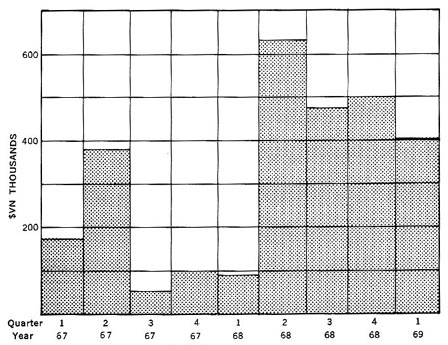

Many troops because of the pressure of combat could not personally participate in Civic Action Programs, so they dug into their pockets to help where they could. (Chart 18) Charlie Battery, 3d Battalion, 34th Artillery undertook to support the Ben Luc Leprosarium. Once a month on payday a collection was taken. The soldiers had a one dollar limit but participation was always 100 percent. They felt it was their leper colony and they took a personal interest in attempting to provide the patients hope for the future.

[170]

CHART 17-U.S. LABOR USED ON CIVIC ACTION PROJECTS

The total number of man days (8 hr days) expended

in support of civic action projects, including

the time expended on construction activities,

MEDCAPS and staff work in support of the civic

action program. Total assistance 48,256 man days

We distributed almost two million pounds of food. As an example, the emergency relief and refugee support mission to the My Tho refugee camp stands out. We worked with the Province Minister of Social Welfare, and nearly 70,000 pounds of division furnished foodstuffs were equitably distributed to 6,000 homeless civilians and refugee families. Additionally, 3,000 gallons of potable water were delivered daily to three refugee camps, hospitals, and orphanages.

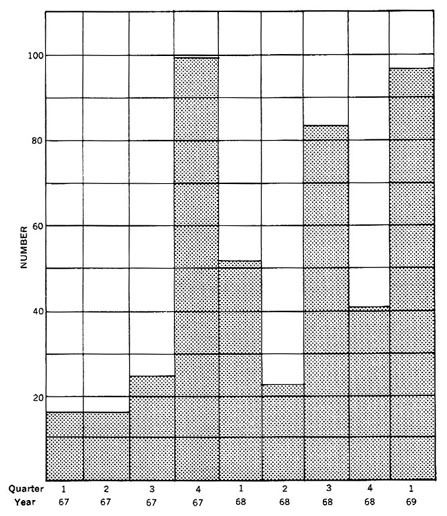

Over 16,000 pounds of clothing and a million and one-half pounds of miscellaneous supplies were also distributed by the 9th Division. The soldiers supported 89 orphanages giving them gifts of clothing, food, money, construction materials, educational and medical supplies, and recreational items. (Chart 19) Around Christmas time a Division medic, after treating one small boy for multiple cuts, presented him with a Christmas toy. The youth left, quite happy with his new toy. However, he returned a few moments later, tugged at his benefactor's trousers leg until he got his attention, then spoke to him through the interpreter, telling him, "To give you pleasure gives me pleasure." This about summarizes the

[171]

This money was Contributed Voluntarily By troops

of the 9th Division and other voluntary organizations

for distribution to churches, orphanages, and

hospitals. Total assistance 2,841,735$VN

feelings involved, the mutual satisfactions, and the increased understandings between soldiers and the civilian populace.

Every unit in Vietnam could quote chapter and verse concerning the generosity of the American fighting man. The wonder is why this steady flow of actions, so open and so discussed, has gone so unnoticed by the casual observer of the war.

The medical efforts of the division in the delta just had to improve the overall health of the region appreciably.

We started at the grass roots. The 9th Medical Battalion initiated a program to train Vietnamese civilian and military personnel in basic medical skills. This increased the indigenous medical capacity as well as the villagers' confidence in the Vietnamese personnel working in local dispensaries. But more important it made the populace less dependent on U.S. aid.

Our most important thrust was the ubiquitous Medical Civic Action Program. Every day, teams comprised of medical and in-

[172]

PERSONAL PACIFICATION

fantry personnel, travelled throughout the friendly areas of the provinces to provide medical treatment to Vietnamese civilians. Over 700,000 patients were treated in a two year period. (Chart 20)

Dental programs were popular and well received. The need for dental care was great in the more remote areas where many of the people had never seen a dentist. Immediate treatment was given those who required it-generally extractions. However, instructions

[173]

Assistance included distribution of clothing, food, money, construction materials, education and medical supplies and recreation items. Total assistance 89 orphanages

in oral hygiene, including leaflets on dental care along with toothpaste and toothbrushes were distributed.

Since our medical program was so well received we reoriented it to integrate civic action with psychological operations and intelligence activities. The Integrated Civic Action Programs operated in contested and insecure areas as differentiated from Medical Civic Action Programs which operated only in secure areas. In addition to the humanitarian aspects, an objective of the Integrated Civic Action Program was to glean such intelligence as: information on the Viet Cong infrastructure; the determination of the status of security and pacification; the establishment of liaison with local leaders and officials in contested areas; and the improvement of our image. Most of the Integrated Civic Action Programs were joint operations with Regional and Popular forces and were conducted in complete coordination with Vietnamese officials, particularly the hamlet and village chiefs and other local leaders. The Integrated Civic Action Programs paid off with impressive results; some of our most meaningful intelligence was gained in this way.

With the Viet Cong on the run, our Integrated Civic Action Program teams began staying overnight, affording us the opportu-

[174]

PROVIDING AID TO THE POPULATION

nity to visit with the local farmers who were largely absent from their homes during daylight hours. It also gave the villagers a feeling of more security and enabled us to double our intelligence inputs. All of these visits were tremendously helpful to the local population because of the medical aspects and the other civic actions features, including games, lotteries, and music. The soldier guitar players and their country music were a big hit with the

[175]

CHART 20-MEDCAP PATIENTS TREATED

These patients were treated on MEDCAPS, ICAPS, NITECAPS and DENTCAPS by medical personnel of the 9th Division. Total assistance 708,588 patients

Vietnamese. It was apparent that the villagers, like our young teenagers in the States, didn't have to understand the words to enjoy the music.

In summary, the medical program with all its many offshoots provided more goodwill than any other single civic action program. It reached more people in more places more frequently and with more tangible results than anything else we did.

The importance of education in the Orient cannot be overestimated. Each head of a family worked to insure that his children obtained the best education possible. Therefore, the efforts put forth by American forces in educational assistance paid off a hundredfold in good will.

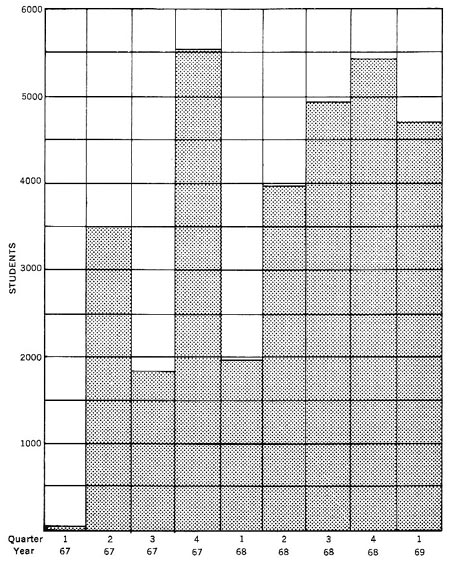

During the 9th Division's tenure we distributed 10,000 school kits consisting of paper, pencils, ink and crayons. Over 31,000 students were taught some basic English as well as crafts, skills, and other technical subjects. (Chart 21) We assisted over 356 schools with supplies as well as construction and repairs. By helping the

[176]

MEDICAL CIVIC ACTION PROGRAM

[177]

The majority of the classes taught were English, however other subjects included crafts, skills and technical subjects. Classes were usually held 2 hours per week. Total assistance 31,717 Students

Vietnamese in their education we helped the aspirations of the Vietnamese themselves.

Repair and Construction of Facilities

The war in Vietnam has destroyed many public buildings. We

[178]

assisted in the rebuilding of 27 churches, 33 dispensaries, 37 market places and almost a thousand dwellings. We provided the Vietnamese with 1,600,000 pounds of cement, about 1,600,000 board feet of lumber and 11,500 sheets of tin to be used for roofing, thus greatly assisting the Vietnamese to assist themselves.

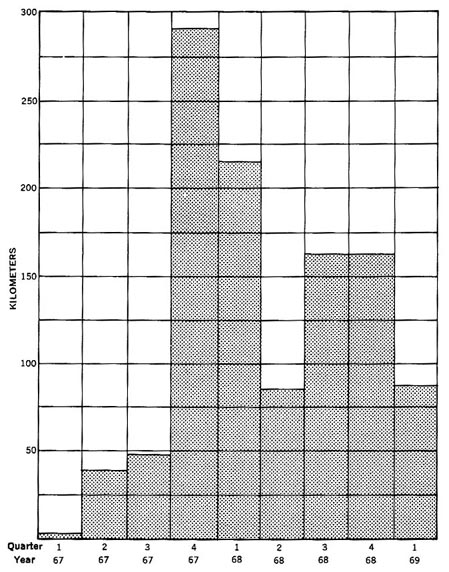

However, it was with our bridge repair and secondary road program that the greatest assistance was rendered. During the period 447 bridges were constructed or repaired and divisional personnel repaired over 1,100 kilometers of roads. (Charts 22 and 23)

CHART 22-BRIDGES CONSTRUCTED OR REPAIRED

Bridges constructed or repaired were for foot or vehicle traffic. All were needed to meet local civilian needs Total assistance 447 Bridges

[179]

CHART 23-ROADS CONSTRUCTED OR REPAIRED

All road work was for civilian and military traffic thereby providing both economic and tactical advantages. Repairs do not include daily clearing of VC roadblocks Total assistance 1107 Km of Road

An almost universal Viet Cong tactic was to cut the existing road network, particularly in rural areas, thus isolating the people in the small hamlets. The Viet Cong then went about systematically breaking up the organizational fabric of the village. They installed their own Village Chiefs and established a complete infrastructure.

[180]

It was this Viet Cong infrastructure, supported by main force and local force troops, that maintained the control of the enemy over the people. To counteract this we initiated a program to restore the road network. It was not an easy task. Inevitably, our road repair and road building efforts drew enemy fire. The Viet Cong strongly resisted any efforts to reestablish communications to the outlying villages. After we understood this we would set elaborate ambush plans and not only did we improve the roads but we took a steady toll amongst the Viet Cong units interdicting our efforts. Interestingly enough, once a road was fully established and the villagers were using it again the Viet Cong rarely recut these farm to market roads because to do so would negate the propaganda which they continuously passed out that the Viet Cong helped the people while the Government Forces did not. The reestablishment of communications with the outlying villages also enabled the Vietnamese Government Forces to erode the Viet Cong infrastructure and thus reestablish control over more of the population of the Northern Delta.

Limiting Damage and Casualties to Civilians

The foregoing civic actions were extremely positive in nature and helpful to the pacification program. However, all of the efforts put into civic actions could be undone in an area by one destructive operation. Our part of the delta, with a little over three percent of the country's land surface, had ten percent of the country's population. When we broke down into small unit operations covering large areas the possibilities for damage increased. To insure minimal possible damage and casualties to civilians we adopted urban rules of engagement as well as our own 1000 meter buffer zone around populated areas to prevent the excessive use of artillery. Although we had very heavy combat over an extended period of time in late 1968 and early 1969, we had only moderate civilian casualties and damage.

In some areas of Vietnam from time to time it has been found necessary to relocate civilians to protect them from the Communists on the one hand and to deny their services to the Communists on the other. In the delta, relocation had never been utilized much. It is really hard to say why. Some of the reasons may have been: there were too many people, the Viet Cong were everywhere, the country needed the rice, the Viet Cong tended to stay far out in deserted areas, the people generally did not like the Viet Cong and the Viet Cong did not trust the people anyway.

[181]

BRIDGE BUILDERS

We wanted to keep the people in place primarily for economic and social reasons. Since the population were kept in place we adopted an unusual style of combing through populated areas with small patrols. After some pressure, the Communists drew back away from the people and did most of their fighting from small local base areas or from the large remote base areas.1

[182]

This afforded us the perfect setup for night ambushes, as we have discussed, since the Viet Cong had to come to the hamlets to get food, female companionship, and information. By setting up ambushes between the hamlets and the base areas we could seriously damage the enemy while breaking his line of communications. This put the Viet Cong in a state of constant tension. Then when the pacification program got into high gear and the hamlets obtained Regional or Popular Force garrisons on a permanent basis, the people were able to turn their backs on the Viet Cong.

Our pacification efforts were not hit and miss. They were well thought out and integrated with combat operations. After the initiation of the Accelerated Pacification Campaign in 1968 we focused on pacification to a larger extent, designing our combat operations to support the key hamlets and critical areas. When our efforts didn't increase the degree of Government of Vietnam control over hamlets we went directly to the evaluation sheets looking for soft spots and then we zeroed in with great precision. We felt that by placing emphasis on pacification we were shortening the war.

The success we had in integrating combat operations and pacification is best illustrated by a ceremony that took place on a hot June day in 1969 at Dong Tam. General Cao Van Vien, the Chairman of the Vietnamese Joint General Staff, had come from Saigon to present to Major General Harris W. Hollis, the fourth of the 9th Infantry Division Commanding Generals in Vietnam (others were Major General George S. Eckhardt, Major General George G. O'Connor, and Major General Julian J. Ewell) , the Division's second Vietnam Presidential Cross of Gallantry Award and at the same time to present to the Division the Vietnam Civic Action Unit Award. To a casual observer the two awards did not seem to be compatible. Yet, to the soldiers participating there was no problem because they had long since learned that combat operations and civic actions were part of the same cloth. Never before that time, we were told, had a military unit been presented a Civic Action Medal. It was understood that the Vietnamese Government had previously presented the Civic Action Unit Award to the two hospital ships that had served the early casualties of the war. Here for the first time a major unit was receiving an award for humanitarian interest in the Vietnamese people while at the same time being cited for gallantry in inflicting over 10,000 casualties on the enemy during a four month period. It was no dichotomy because in our total integrated analytical approach, combat operations and pacification went hand in hand.

[183]

Endnotes for Chapter VIII

1 Civilians detained in the course of hostilities were presumed innocent, unless there was evidence to the contrary, and were handled separately from prisoners of war. Civilians were given good treatment and were returned to their homes expeditiously in order to generate goodwill. Amenities at the Ninth Division Civilian Center were better than in the typical peasant home, and detainees apparently appreciated the considerate treatment they received. While these civilians probably were not protected under the provisions of the Geneva Conventions, regulations governing their treatment met or exceeded the standards of the Conventions. (click here to go back)

page updated 19 November 2002

Return to the Table of Contents