CHAPTER X

Corps Level Operations

In April 1969 the focus of this study shifts to II Field Force Vietnam at Long Binh, with the 9th Division portion continuing until mid-1969.

At corps level we see a much more complex problem and one inherently more difficult to manage and analyze. However, after a period of observation we slowly began to institute a simplified version of the 9th Division review and analysis system at the division and separate brigade levels. Some segments of operations were subjected to straight-on analysis with the remainder being handled by normal military decision methods but subjected to the general philosophy of the "analytic approach." While the improvements in performance were less dramatic than in the 9th, they were substantial enough to justify the added effort.

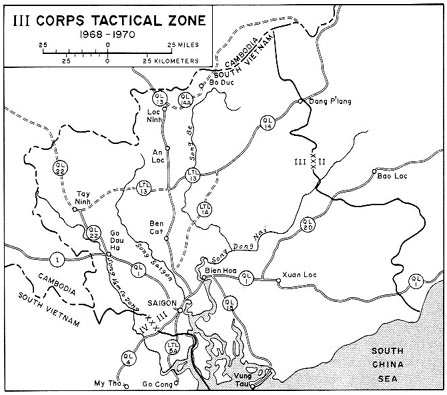

At II Field Force Vietnam level, we had the equivalent of five U.S. and Free World divisions as well as operational control of the advisory structure for eleven provinces and the equivalent of five South Vietnamese Army divisions. (Map 2)

Our enemy was principally North Vietnamese Army main force. What Viet Cong units were left were, in fact, North Vietnamese Army in all but name, as they survived only on the strength of North Vietnamese replacements.

The true diversity of III Corps Tactical Zone strikes one when you examine the kind of warfare experienced there. There were almost as many different wars as there were units since the military region encompassed a wide range of terrain and enemy situations. (Map 2)

For example, in Saigon we had what was principally a National Police and intelligence effort against the terrorists and the Viet Cong Infrastructure.

Moving out to Gia Dinh and the outskirts of Saigon, one found four Vietnamese Army regiments and three U.S. brigades engaged in screening in the relatively open terrain against rocket attacks and infiltrators into the city.

To the south, in Long An Province, the 3d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division was efficiently engaged in smoking out the Viet Cong

[191]

MAP 2

remnants (and 1st North Vietnamese Army Regiment) and chopping them up. This was the typical delta-type operation perfected by the 9th Division.

To the northwest of Saigon, the U.S. 25th Division faced two different wars. In Hau Nghia, a long-time citadel of the Viet Cong, one faced the combined efforts of enemy units and of a population that continued to support the Communists either through choice or necessity. The terrain was wide open-the resident Communists lived in hedgerows and spider holes. There were booby traps and mines in abundance. Principal combat was with elements of SubRegion 1 who were based in the Boi Loi Woods and the Trapezoid.

In Tay Ninh there was an entirely different environment. Bordered on three sides by relatively heavy jungle and situated only four hours walk from the Cambodian border, it existed in a feast or famine fashion. At his choosing, the enemy moved from his sanctuaries in Cambodia to attack the populated areas. When this happened, one experienced all ranges of combat, from deep jungle to

[192]

fighting in built-up areas. When the main forces withdrew to Cambodia, however, there was practically no one to fight since even the local forces based themselves in Cambodia.

The 1st Cavalry Division which spanned the northern tier of War Zone C, Binh Long and Phuoc Long had a particularly difficult situation facing it. The terrain was deep jungle and in it were elements of three Communist divisions plus the rear service groups, and Lines of Communication that passed men and supplies from the Cambodian sanctuaries to the sub-regions that ringed Saigon. (Sizeable elements of all of these were based in Cambodia) . Combat here was typified by all the difficulties inherent to deep jungle and bunker warfare.

In Binh Duong to the north of Saigon, the 1st Infantry Division faced terrain that varied from deep jungle to open cultivated and built-up areas. In it, they faced local forces, several beat-up and elusive one-time Viet Cong regiments (Qyuet Thang and Dong Ngai) and parts of Sub-Region I. To a large extent, the big war had gone and left the Big Red One behind. Because of its past success in beating down the enemy, it now found little left to fight in its traditional area of operation. What enemy remained was highly elusive and consistently avoided contact.

Finally, to the east and southeast of Saigon, the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force and the Australian Task Force faced a rough and durable assortment of one Viet Cong regiment and some battalions that habitually survived in deep jungle bases near inhabited areas. Major contacts were infrequent.

Because of this diverse and different situation, there was initially a reluctance to apply at Corps level the review and analysis techniques that had been so useful at division. Initially, the general nature of the 9th Division system was brought to the attention of the subordinate commands of II Field Force Vietnam. By so doing, we provided examples of the statistics we had collected and the practical management use derived from them. Subordinate commanders were encouraged to analyze their local situation and if they did not already have one, develop a Review and Analysis System for their own use. This effort was not limited to the tactical units. For instance, the Deputy for Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support worked out a system which highlighted the key measurable areas in the pacification field.

This effort started to show results almost immediately. Although the divisions in II Field Force, Vietnam had previously conducted varying types of analysis, none had kept books on an input-output or expenditure of effort versus results basis. Hence, the more adept

[193]

were quickly able to obtain the benefits we had noted in the 9th Division:

(1) The ability to determine more rapidly and clearly the types of operations

that were paying off with results and where.

(2) The efficiency and effectiveness of various units.

(3) An identification of unproductive expenditures of time and effort.

As has been mentioned throughout this monograph, the 25th Infantry Division employed simple operations analysis consistently. They also developed the use of computer assistance in operations analysis to a significant degree. The comments of Major General Harris W. Hollis, the 25th Division Commander in late 1969 and early 1970, are of particular interest:

I found it was extremely important that I closely examine our operational results on a continuing basis, so that I could gain an adequate appreciation for the overall picture of how the command was progressing.

I am convinced that operational analysis techniques have tremendous potential for application in future combat and particularly in the complex environment of this type of war. I saw how others had used this method with success; particularly General Ewell, when he commanded the 9th Infantry Division prior to my succession to command of that division. In no other war have we been so deluged by so many tidbits of information, for we have been accustomed to an orderliness associated with established battlelines. Here, though, we have had to make our decisions based not upon enemy regimental courses of action, but rather upon the numerous isolated actions of communist squad-sized elements. So with the scale down of the level of operations, we have had to increase our reliance on objective analysis of available information to arrive at logical courses of action.

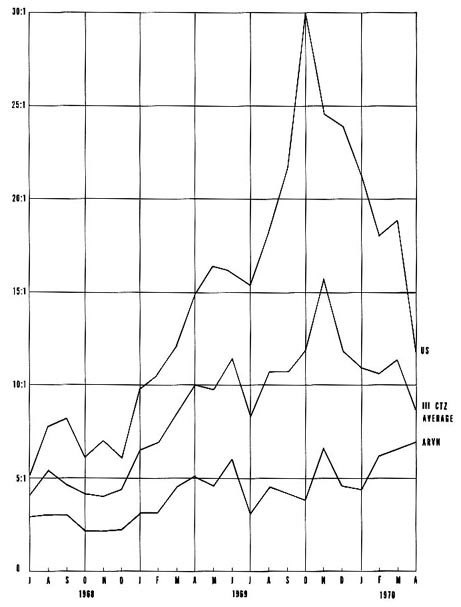

Armed with this information, the more receptive commanders were able to optimize their efforts quickly and put their assets where they were getting better results. As they did, the II Field Force, Vietnam exchange ratio, which had averaged below 10 to 1 for the previous nine months, began to improve. For five straight months, the rate was over 20 to 1. During October 1969 the rate crested at 30.1 to 1. For the 12-month period April 1969 through March 1970, the U.S. units in II Field Force, Vietnam had an average exchange rate of 18.9 to 1. (Table 30) This improvement came from increased efficiency of U.S. units, who took fewer casualties to do the job while enemy eliminations gradually went down. One of the payoffs at division was the quick indication of changed enemy tactics. For example, when things got too hot for him at night, the enemy often would change to early morning or early evening resupply and so on. The new insights provided by this system of analysis showed

[194]

TABLE 30-U.S. FORCES, II FIELD FORCE, VIETNAM EXCHANGE RATIO APRIL 1969-MARCH 1970

| Date | Enemy KIA | U.S. KIA | Exchange Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apr 69 | 4014* | 270 | 14.9 : 1 |

| May | 4128* | 252 | 16.4: 1 |

| Jun | 4655* | 287 | 16.3: 1 |

| Jul | 2764 | 180 | 15.4: 1 |

| Aug | 3726 | 203 | 18.4:1 |

| Sep | 3371 | 156 | 21.6: 1 |

| Oct | 2748 | 91 | 30.1: 1 |

| Nov | 3651 | 148 | 24.7: 1 |

| Dec | 3130 | 130 | 24.1: 1 |

| Jan 70 | 2366 | 111 | 21.4: 1 |

| Feb | 1750 | 97 | 18.0: 1 |

| Mar | 2383 | 127 | 18.8: 1 |

| Average | 3224 | 171 | 18.9: 1 |

* A period of heavy combat along the Cambodian border.

commanders when to adjust their tactics to compensate for enemy changes. Much greater efficiencies resulted.

As each division's data bank grew, we drew on them for certain selected summary data for Headquarters II Field Force, Vietnam. Because of the very diverse terrain and enemy situation noted above, direct comparison of division-level statistics was generally not feasible or profitable. However, these summary statistics did provide a valuable insight into what both friendly and enemy forces were doing (or not doing) .

Thus, our analysis was able to confirm our suspicion that the Communists were fragmenting further after the failure of their main force attacks in the spring and summer of 1969. (See Table 30.) Our daily situation briefing gave us the impression of smaller contacts. Our weekly review of statistics brought the facts clearly into focus. We had not fully comprehended the damage done to the enemy during the friendly operations commanded by Generals Frederick C. Weyand and Walter T. Kerwin, Jr., in 1968 and 1969.

Further, Corps-level statistics gave the commander another indicator on potential trouble spots. When the summary statistics began to slip, it was time to pay- a visit to the unit to see what the trouble was. Because of the almost unmanageable span of supervision, this tip-off feature was of great value.

However, as has been mentioned earlier, it was much more difficult to apply analytical methods to this much more complex operation. Review and analysis tended to be of the more conventional

[195]

management type. If one can summarize the approach, it was to use analysis where feasible, use tight management overall, and to try to preserve the questioning, results-oriented analytical approach throughout.

Some selected examples of the various uses of analysis follow.

Pragmatic and cumulative experience during the Vietnam war revealed more and more clearly that one had to work on all elements of the enemy's system to achieve substantial success. This was particularly true when the Communists were operating from Cambodian sanctuaries as was the case in III Corps Tactical Zone.

This concept was crystallized and articulated by General Creighton W. Abrams. When combined with the lower level constant pressure approach it was most effective. It should be noted, however, that III Corps was unusual in that the terrain, the weather and troop availability favored the concept. We followed a highly successful program of keeping constant pressure on most elements of the enemy system although a few areas were beyond our capabilities. Geographically, this meant the Viet Cong infrastructure and local elements in the cities and surrounding populated areas, the local forces that operated around the populated areas, the subregions and their main force elements that tenanted the close-in base areas, the rear service groups that maintained the lines of communication from Cambodia, and finally the North Vietnamese Army divisions which by now clung, more and more, to the safety of the Cambodian border were all attacked simultaneously. By 1969 most enemy units were fairly well beaten down. However, from time to time, we had to drop what we were doing and turn all hands to smothering some Communist attempt at a high point. However, once the fire was put out, we immediately went back where we had left off to an overall constant pressure approach.

By September 1969 we had beaten back the final gasp effort of the North Vietnamese Army divisions to get to Saigon and Tay Ninh and their consolidation efforts against Binh Long Province. This done, we fine-tuned our efforts to insure that we had pressure on every possible element of the enemy system. In line with the improved capabilities of Regional Forces, we thinned out the regular forces protecting Saigon. In accord with the Vietnamization program, every effort was coordinated with Vietnamese forces. Fortunately, the Vietnamization program had proceeded to the point where many South Vietnamese Army units could pull their own

[196]

MAP 3

weight in good fashion. This gave us 50 to 60 more reasonably good battalions to work with.

Across the northern tier of III Corps. (Map 3) we deployed a coordinated force of seven U.S. and South Vietnamese brigade equivalents. They worked against the three essentially North Vietnamese Army divisions and the lines of communication that led from Cambodia into the interior of III Corps.

In War Zone C a brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division and a South Vietnamese airborne brigade moved in on top of the enemy line of communications that ran from the Fishhook down the Saigon River corridor to the Michelin-Trapezoid base area. They were in constant contact with and exacted a slow and steady toll on elements of the 9th North Vietnamese Army Division and on rear service elements on the line of communications.

To the east, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and the 9th South Vietnamese Army Regiment worked along Highway QL 13

[197]

and west to Ton Le Cham and the Fishhook, keeping pressure on the 7th Division elements that rotated across the border and denied the enemy access to the population in the area.

Moving further east, one found a brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division with its battalions deployed in a linear fashion along the Song Be River infiltration route. By intensive reconnaissance it sought out the trail locations and operated along them, taking small but steady bites out of the Communist supplies and people.

Finally, at Song Be we had the remaining brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division and another South Vietnamese Army airborne brigade. They kept pressure on the elements of the 5th Division which were still in South Vietnam and sought out enemy logistics movements from Base Area 351 in Cambodia towards War Zone D. For several months, we achieved moderate but steady success. In the fall of 1969, air cavalry elements discovered that the Communists had established a new line of communications from Base Area 351 along the II Corps-III Corps boundary into War Zone D. (The so-called Jolley trail) Our reaction was to immediately put troops on top of the new trail to keep up the pressure and attrition. Starting from the point where this new trail crossed QL 14 northeast of Duc Phong, the cavalry and airborne leapfrogged battalions along the trail scooping up important quantities of supplies and killing rear service troops. Of equal importance this effort impaired the flow of supplies and munitions to the sub-regions around Saigon.

In summary, the combined U.S.-South Vietnamese Army effort across the northern tier was designed to accomplish two objectives. First, to erode the main force units and keep them so weak and occupied that they could not interfere with the pacification program. Second, to reduce and, if possible, choke off the flow of replacements and supplies from Cambodian sanctuary base areas into the heart of III Corps. These efforts were surprisingly successful.

In the interior of III Corps, we had a force of 18 brigade equivalents deployed in a great circle 30 to 70 kilometers out from Saigon. This force was dedicated to the tasks of maintaining pressure and attrition on the sub-regions, the close-in base areas and the lines of communications that came into the sub-regions.

Northwest of Saigon, the 25th U.S. Division and two regiments of the 25th South Vietnamese Army Division were on top of Sub-Region 1 and Sub-Region 2 keeping pressure on the main force elements and the lines of communication from the Angel's Wing. This was a particularly difficult task because of the easy Communist access to bases in nearby Cambodia.

North of Saigon, the U.S. 1st Division and two regiments of the

[198]

5th South Vietnamese Army Division were focused on Sub-Region 5 and they participated with neighboring units in a coordinated effort against Sub-Region 1.

East of Saigon, the 18th South Vietnamese Army Division, the U.S. 199th Light Infantry Brigade, the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force and the Australian Task Force combined their efforts against Military Region 7 and Sub-Region 4. Typical of their operations was a coordinated campaign to wear down the 274th Viet Cong Regiment and drive it out of its long-term base area in the Hat Dich jungle. This involved putting troops, firebases and Rome Plows into the base area and intensive efforts to interdict resupply into the base.

In the Rung Sat Special Zone, a delta area south of Saigon, a special U.S. Navy-Vietnamese Navy effort kept continuous pressure on the water sapper elements that formerly had interdicted shipping channels. These efforts were fully coordinated with and from time to time supported by II Field Force, Vietnam.

Finally, in Long An Province, the 3d Brigade 9th Division and the 46th South Vietnamese Army Regiment combined their efforts to control Sub-Region 3 and defeat the 1st North Vietnamese Army Regiment.

This completed the middle ring. In it we kept full pressure on the organized Communist forces, eroding them, and creating an environment for pacification progress.

Gia Dinh Province and Saigon are the heart of III Corps. Because of the bitter memories of Tet 1968 and avowed Communist aims for 1969, we started the year with a force of four South Vietnamese Army regiments and three U.S. brigades deployed in defense of Saigon. They did their job well. Although the Communist main forces never got close, these forces kept Sub-Region 6 under a blanket. Hence, we started pulling out forces in June 1969 and completed the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Sub-Region 6 in September 1969. The airborne forces were withdrawn next and Rangers started soon after. As this occurred, the Regional and Popular Forces assumed more and more of the load-a graphic example of Vietnamization in action.

While all these actions were going on, there was a concurrent steady improvement in Regional Forces throughout III Corps. This resulted from the steps being taken to upgrade their training and equipment, the gradually improving leadership at district and province level, and the improved environment which we provided by keeping the main forces on the run and away from the populated areas. This freed the Regional Forces to work on the local Com-

[199]

munist elements without fear of being engulfed by a main force unit.

As they enjoyed increasing success, they began to deny the enemy access to the population. The Communists were thus able to extort less and less support from the people. This, of course, put more of a burden on the already strained Communist supply system. What they could not get locally, they had to bring in from outside.

It was a vicious cycle-by keeping an unrelenting pressure and attrition on all elements of the enemy system, we pushed him closer and closer to the breaking point. He reached a point where most of his effort was devoted to his own survival. This entire operation required exquisite co-ordination and delicate emphasis.

By March of 1970 the enemy in III Corps was very weak. The Cambodian operation then destroyed his bases in the Cambodian sanctuary, dealing him a staggering blow.

We have remarked elsewhere on the positive effect of gifted commanders. It seems appropriate here to mention that an "average" or less commander during the 1969-1970 period found it difficult to do damage to the enemy in a useful way. Not only did the situation require considerable technical and tactical proficiency but also a complete determination to come to grips with the enemy.

In our effort against the enemy system, we wanted to insure that we were not missing any Communist units. Hence, we made a systematic inventory of all Communist elements of any size known or suspected to be in III Corps. Next, we stratified the units by their known or suspected geographical area of operation. Against this list we arrayed the South Vietnamese and Free World Forces who operated in the area. Finally, we analyzed our past operations to determine how effectively we were doing the job.

This systematic inventory was a refinement which was initiated late in the game. It almost immediately focused our attention on an unusual problem area.

As one might expect we found out that the main force units were getting most of our attention. They were, after all, the most obvious threat and the ones who could inflict a small tragedy on us in an afternoon. The local force battalions were also systematically pursued by our side. Shifting to the very base of the Communist pyramid, the Viet Cong infrastructure was the object of a formal program designed to eliminate it. Although spotty in effectiveness, the Phoung Huang program showed promise.

However, in the middle of the pyramid (See Chart 8.) we found

[200]

an entirely different picture. In many instances, local-level Viet Cong elements were existing relatively unmolested under the very noses of friendly units that were keying on bigger game. There was no systematic effort to search out and eradicate these local pests. They suffered attrition only when they were caught by a reconnaissance-in-force, a night ambush, or while they were attempting an offensive action. No one was keeping the pressure on them.

Armed with this information, we went one step further. We charged subordinate units with responsibility for the specific small elements known or suspected to be in their areas of operation. This was a combined Free World-South Vietnamese Army program resulting in close coordination of all forces down to district level. Periodic reporting on results was required so as to assess progress. The 25th Division refined this process to a high art.

Within several months, we could see positive results from this effort. Marginal Viet Cong units that had survived at minimum strength when they were left alone began to fold up under pressure. Many were simply inactivated because of ineffective remaining strength.

This was all accomplished without flash or fanfare. Attrition was by twos or threes. When the word got out that we were looking for locals by name, the pressure caused them to move out, hide deep, or Chieu Hoi.

The overall result was to hasten the decay of local forces and to further weaken the link between the Communist apparatus and the people. This device institutionalized the Constant Pressure Concept and allowed one to keep tabs on its success.

On a mufti-division scale, our effort against Sub-Region 1 was an excellent example of the Constant Pressure Concept. For a period of years, this key sub-region had survived under the noses of two U.S. and two South Vietnamese Army divisions. It did so by being slippery and alert. During these years, it had suffered enormous casualties but relying on North Vietnamese Army replacements, it always managed to survive and to rebuild. The North Vietnamese Army headquarters was usually underground in the deep jungle of the Trapezoid. (Map 4) Its subordinate elements holed up along the Saigon River in secondary growth Rome-plowed areas, in the Boi Loi Woods, and in the Trapezoid. They lived off two separate lines of communication-one across Hau Nghia Province to the Angel's Wing in Cambodia and the other from the Fishook south down the Saigon River corridor. (Map 4)

[201]

MAP 4

[202]

Aiding Sub-Region 1's survival was the fact that it was near the boundary between our divisions and as pressure mounted on one side it could slide away. Our units tended to concentrate on what was in their area of operation. Cross-boundary co-ordination was not a strong point.

Starting in July 1969, we hit the problem head on with a full court press by all U.S. and South Vietnamese Army forces in the area. First, we moved the divisional boundary to the Saigon River the 1st U.S. Division and 5th South Vietnamese Army Division to the northeast of the river and the 25th U.S. Division and 25th South Vietnamese Army Division to the southwest. U.S. Navy and Vietnamese Navy boats worked the river. A floating boundary was established on either side of the river to enable rapid exchanges of territory and responsibility.

To kick off the effort, a co-ordination conference was held by all participants to exchange intelligence and co-ordinate operational details. The Commanding General, 1st Infantry Division, was designated co-ordinator for the operation. He maintained the books on current operations, insured an exchange of information with all participants, hosted weekly staff co-ordination meetings, and monthly commanders' conferences. Within the first week, Sub-Region 1, was on its way down. Co-ordinated effort by ground forces and Navy elements along the river started exacting a nightly toll on resupply efforts across the river. At the same time, a South Vietnamese Army airborne battalion and a U.S. battalion moved in on top of the 268th Viet Cong Regiment in Boi Loi Woods and the 1st Division and 5th South Vietnamese Army started a major tactical effort supported by Rome plows in the Trapezoid. Although not a formal element of the Sub-Regional 1 effort, the 1st Air Cavalry to the north choked down on the enemy and impaired his resupply via the Saigon River corridor.

Progress was not spectacular. There were no big fights but every day there was a steady toll of the enemy. Prisoners told tales of not wanting to go on rice resupply details because it was sure death. In addition, major headquarters type elements of both Sub-Region 1 and the 268th Regiment were overrun and captured. The pressure was so great that the 101st North Vietnamese Army Regiment moved completely out of the area.

We were, of course, very pleased with the erosion that Sub-Region 1 suffered in this operation as it was the strategic link pin of the entire Communist effort towards Saigon. There was an important bonus. This was our first real test of the Dong Tien (Progress Together) program. The improved performance of the 8th

[203]

South Vietnamese Army Regiment working with the 1st Infantry Division showed us clearly that we had chosen the right path in that the South Vietnamese Army was ready to assume a major combat load.

While we were keeping full pressure on Sub-Region 1, pacification in nearby populated areas was proceeding in a very satisfactory fashion. Sub-Region 1 units were fully occupied in self-survival and could not interfere. Under the umbrella of our pressure, Regional Forces, Popular Forces, and Popular Self Defense Forces gained strength and capability.

By early 1970, when the first sizable U.S. troop withdrawal took place, Sub-Region 1 was so debilitated and the South Vietnamese Army and regional forces so improved there was no noticeable change in security ratings.

In June 1969 we started a major effort to upgrade South Vietnamese forces in III Corps as part of the Vietnamization program. The program, announced jointly by the Commanders of III Corps Tactical Zone and II Field Force Vietnam, was called the Dong Tien (Progress Together) Program. It paired U.S. units with South Vietnamese Army and Regional and Popular Force units for operations-the objective being to allow each force to learn something from the other. Because of the key importance of airmobile skills in the Vietnamization program, we put particular stress on combined airmobile operations. Each U.S. commander shared his air assets with Vietnamese units. At first Vietnamese elements merely went along on U.S.-planned and managed operations but progressively the Vietnamese took over and ran their own operations.

There were two very obvious benefits that accrued from this effort in short order. First, Vietnamese commanders and units developed real skill in using airmobile assets (without depending on U.S. advisors as in the past). Secondly, Vietnamese units using air assets followed the U.S. example and started operating in areas they had avoided for many years.

The program was then extended to operations as a whole. The payoff here was substantial. The Vietnamese began to operate continuously-both day and night-and in some cases performed as well or better than their U.S. partners. As a battalion or regiment showed that it was really effective, it was "graduated" from the system and took over an independent mission.

This program was nothing new. It was directly copied from I Corps where we concluded that an important element in the suc-

[204]

DONG TIEN

cess of the 1st South Vietnamese Army Division was an informal arrangement of the same sort. The only "new" element was to formalize the system as a command directed program. This was done because the South Vietnamese Army in the III Corps area had historically resisted combined operations. It also gave the program more status and visibility.

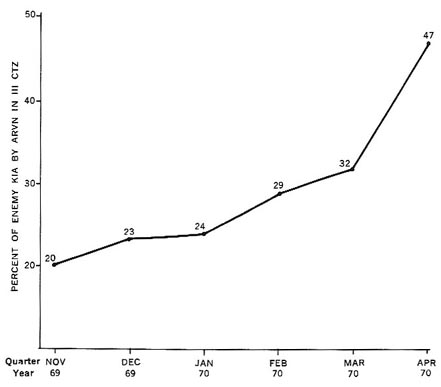

The upshot and final test of the system came as U.S. units began to withdraw from III Corps. The success of the Dong Tien program was attested to by the manner in which Vietnamese units were able to pick up the load and effectively keep the pressure on the enemy. Throughout mid-1969, U.S. and other Free World Forces were carrying about 80 percent of the combat load in III Corps as measured by the numbers of enemy killed in action. Beginning in November 1969 South Vietnamese units began to increase their share, until by April 1970 the situation had changed dramatically with the South Vietnamese Army carrying almost one half of the combat load. This was partially due to the redeployment of some U.S. units. Chart 25 indicates one way in which we pragmatically measured the actual progress of the Vietnamization Program. The

[205]

CHART 25-SOUTH VIETNAMESE ARMY CONTRIBUTIONS TO III CORPS TACTICAL ZONE COMBAT LOAD

South Vietnamese Army units that operated so effectively in Cambodia with no U.S. advisors were the products of this Dong Tien program.

Following the defeat of Communist main force efforts in the Tet period of 1969, we took a hard look at our method of allocating assault helicopter company and air cavalry support. The purpose was to see if we were getting all that was possible from these relatively scarce and valuable units.

At the time, our Standing Operating Procedure was to make a daily allocation of assault helicopter companies to U.S. and South Vietnamese units. Units that wanted air assets for a particular day put in their bids. We sorted out the requests and assigned use of the assets based on our evaluation of the Corps-wide situation and the unit's part in it. Since there were never enough helicopters to fill all valid requests, some requests always went unfilled. Because of the dynamics of the situation, a unit could not plan very far in advance.

[206]

Until all requests were considered, a unit did not know if it would get the air assets which it had requested. This was, of course, the standard system of allocating from a central pool when requirements exceed resources.

To get a handle on the problem, we turned to our basic set of statistics on combat results. We found that certain of our units consistently achieved more enemy eliminations on airmobile operations than did others. However, these units did not necessarily receive priority in the allocation of air assets, since allocation was based on what a unit said it was going to do without consideration of its past achievements. At the same time, the uncertainty of getting assets impaired the units' efficiency in keeping full pressure on the enemy.

In an effort to improve results, we stopped daily allocation of assets and went to a monthly allocation, which was weighted in favor of the units that were producing results or had a high priority mission overall. For instance, the 3d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division, our most proficient user of air assets, which worked Long An Province-the first priority pacification target nationwide-received 45 Assault Helicopter Company days per month, while a like sized unit and area with a poor track record and a less important mission, received only 25 Assault Helicopter Company days per month.

For planning purposes the allocation was spread over the month, and a tentative schedule issued. Thus, a unit knew in advance what it would have for air assets on a given day and could plan the rhythm of its operations accordingly. This schedule was not set in concrete, however. When the situation dictated, we pulled the assets and put them where they were needed at the moment.

In announcing the new system, we made it clear that allocations were "results" oriented and that those units which used assets most efficiently would continue to receive a proportionately greater share of available assets. However this was more of a gambit to stimulate good performance than a factual description of the actual allocation process.

Our experience proved that this change was both timely and beneficial. Coming at a time when the enemy was changing his tactics (breaking down to small units) , it allowed units to plan effectively for future operations and gave them incentive to try more imaginative ways to employ their assets. It also allowed us to assign the same air units to the supported ground unit, thus facilitating the development of closer coordination and teamwork. In other words, the units could work their way up the learning curve.

[207]

TRANSPORTING ARTILLERY FIRING PLATFORMS

This is cited as an example of departure from the "standard" or "reasonable" system to achieve better results.

Full Response to Antiaircraft Fire

In the summer of 1969 the three Communist main force divisions in the III Corps Tactical Zone north of Saigon were in the process of being driven up against the Cambodian sanctuary areas. In flying over War Zone C, it became apparent that we were receiving rather heavy .50 caliber antiaircraft fire. We soon found out from captured documents that the Communists had initiated an intensive campaign to shoot down American choppers. As a result, our aircraft losses went up, although modestly. After observing the enemy tactics, it was theorized that they were selecting an area along the upper Saigon River logistical and infiltration corridor which they wished to protect, positioning an antiaircraft battalion in it and then letting fly.

The normal U.S. response in the past had been to attack any guns which were a problem and detour around the rest. However,

[208]

in this case, it was decided, for largely psychological reasons, to try to defeat the tactic head on.

It was decided to:

(1) Report and record all firings. (Maximizing our information.)

(2) Attack all located guns with maximum firepower (gunships,

artillery and Tactical air).

(3) Work the area over on the ground when feasible and desirable.

After a period of weeks, our aircraft losses went back to normal or below. It was found that it took only a matter of days to either destroy or neutralize an entire battalion (say 9 to 15 guns) . Whether this was due to destroying the guns, killing off the crews, or exhausting their ammunition supply was not known. However, it was quite apparent that they were cycling in fresh battalions to replace the old. After some months the enemy gave up, but the full response technique on a less generous scale was retained against any fire (light machinegun or rifle). Eventually the enemy antiaircraft fire subsided to normal proportions or less. Unfortunately, the statistics on this interesting operation could not be located.

In retrospect, it is observed that most of the improvements or innovations described in this monograph were ideas which usually involved people-whether concepts, management, tactics, techniques or training. This was a surprise-that doing something a little different or a little better with people could result in substantial improvements. However, the Night Hawk Kit was an example of a hardware solution developed by analysis.

Earlier we described the success of the Night Search technique, Although very profitable, a Night Search operation involved a major investment of two Cobras and one Huey plus additional backup helicopters and required a high degree of skill on the part of the sniper spotters.

The 25th Infantry Division studied this technique and, over a period of time, developed a kit consisting of a coaxially mounted mini-gun, Night Observation Device, and a small pink and white searchlight. This was ideal as the Night Observation Device gave maximum efficiency for normal night observation, the pink searchlight could he used for very dark night conditions, and the mini-gun had ample firepower for the job and replaced both Cobras. Being a "plug-in" kit for a Huey, it could be removed in the day

[209]

and installed in any operational plane at night. The coaxial feature allowed one man to operate it, thus removing the need for "handing off" targets. The final refinement was the use of both a right and left hand kit which eliminated the effect of stoppages.

This clever development with on-hand components allowed one plane to do the job of three or more and gave better results with less highly trained operators. This program was so successful that U.S. Army, Vietnam eventually fabricated the kits and issued them to all units, thus providing an improvised night gunship which could perform fairly sophisticated tasks under night light conditions.

In Vietnam, ARC LIGHT (B-52) strikes were one of the most valuable and effective weapons available to higher commanders. However, as with many good things, they were limited in number and hard to come by. Demand always exceeded availability. During the period covered by this report, available sorties per day varied from 60 down to 47 for the entire theater. Allocation of sorties rested at Headquarters Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. There was no suballocation of strikes. Rather, subordinate units nominated targets to Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam who approved strikes based on the overall situation in Southeast Asia and the quality of the target. By quality, one means the importance of the target, plus the reliability of the intelligence concerning it and its location.

At Headquarters II Field Force, Vietnam, we utilized a very thorough system of analysis to insure that we represented accurately the importance of our nominations and at the same time did not misuse this asset. To perform this task we created an ad hoc ARC LIGHT element in our G-2 and G-3 AIR shop. They systematically collected every fragment of information available on high priority Communist units and areas in which they were known or suspected to operate. This included:

-Red haze 1 and side looking airborne radar returns

-Ground firings at aircraft

-Visual reconnaissance results

-Aerial photo readout

-Reports from agents, prisoners of war, and Hoi Chanhs

-Results from ground reconnaissance and ground contacts

-Sensor activations

-Other special sources of intelligence

[210]

-Historic patterns of enemy activity-what had he done before and where?

These data were collected and plotted on receipt, resulting in a tactical temperature chart on key areas of the battlefield.

Information from this data bank was available on request to supplement that collected by subordinate units but was used principally at Field Force level to evaluate subordinate unit nominations. On occasion, where a lucrative target escaped the attention of subordinate levels or a target of opportunity emerged, this data bank was used to develop Field Force level targets.

What this system did in particular was to play down the element of emotion and subjectivity in the target selection process. This was particularly important in evaluating targets nominated by South Vietnamese Army units, since they often did not have as much good current technical intelligence available as did we. Their nominations may have been quite valid, but did not always stand up under an analytical screening. Although certainly not foolproof, our system could address the probability of our finding enemy in a target box.

Because of the perishability of intelligence, this data bank could never guarantee the existence of a target in a specific box-particularly since at this point in the war the enemy was fully alert to the B-52 threat and practiced effective passive defense measures.

The great value of the system was that it was rationally organized, so that it could rapidly provide facts to the commander to assist him in target appraisal.

Successful tactics and targeting still depended in great measure on the skill, instinct, and intuition of a commander who knew his enemy. This data bank was designed to assist the commander in fine-tuning the location of targets. In addition the nature of the data bank was such that the addition of one new fragment of information often gave us the opportunity for a highly lucrative last minute diversion of an allocated strike.

The test of any system is the results obtained by it. By this measure ours fully justified the great amount of work that went into it.

We did not nominate targets unless we believed them to be worthwhile. In the great majority of cases, we got what we requested. This was because we had organized facts to back up our nominations and because our active program of ground bomb damage assessment confirmed our prediction of target nature in a high percentage of strikes.

[211]

As a matter of historical interest, the use of ARC LIGHTS in the 9th Division area in the delta was almost nil. The populated areas were almost automatically excluded and suitable targets elsewhere were quite infrequent. In the II Field Force Vietnam area in 1969-1970, practically all strikes were way out in deep jungle. However, one can assume the strikes were bothering the North Vietnamese, as their propaganda campaign had as a primary theme the concocted idea that tremendous damage was being done to the South Vietnamese people by indiscriminate use of ARC LIGHTS.

With the passage of time in Vietnam, we developed a feel for our operations and the enemy, which enabled us to pick up strong or weak points by focusing on certain elements. These elements varied from individual areas to broad spectrums of activity. Some illustrations follow:

Gross eliminations were important but highly variable as to significance. A good unit in an area with lots of enemy consistently did a lot of damage. A unit in such an area that didn't cut up the enemy needed expert help to determine what it was doing wrong. Obviously, some units were in a dry hole (not much enemy around) and showed low elimination rates. It took considerable skill to determine the unit's knowledge of the enemy situation and its basic skill level in order to ascertain if their lack of results was due to lack of knowledge and skill or lack of enemy. As the enemy strength in an area declined this factor became more and more unreliable.

The exchange ratio (kill ratio) was of considerable value in assessing the professional skill of a unit. The matrix below gives a general idea:

| Exchange Ratio | Skill Level of Unit |

| 1 to 50 and above | Highly skilled U.S. unit |

| 1 to 25 | Very good in heavy jungle |

| Fairly good U.S. unit in open terrain | |

| Very good for ARVN in open terrain | |

| 1 to 15 | Low but acceptable for U.S. unit |

| Good for South Vietnamese Army unit | |

| 1 to 10 | Historical U.S. average |

| 1 to 6 | Historical South Vietnamese Army average |

These exchange ratios applied to combined arms teams, including of course, airmobile and air cavalry support. The figures were highly

[212]

variable due to local conditions. Also as the enemy strength declined, they became more erratic and of less utility.

In connection with the above, we made several efforts to reflect the greater importance of prisoners, Hoi Chanh and Viet Cong Infrastructure eliminations but were never satisfied with our approach. Our final solution was to include them in gross eliminations but with no weighted value. We did not include them in exchange ratios but carried them separately and tried to maximize our intake directly. The figures were inherently unstable over a short period of time but cumulatively fairly stable and showed trends. A low prisoner figure probably indicated lack of strong command emphasis. The Hoi Chanh figure was a valuable measure of overall military pressure although it varied widely according to the stage of progress of military and pacification operations in which one found one's self. As a result, it took much knowledge to interpret correctly. The Viet Cong infrastructure figure was highly erratic and was used only to focus command attention on the area. Although Viet Cong Infrastructive operations were primarily a Government of Vietnam operation, military support by U.S. and South Vietnamese Army forces was often an important assist in getting the Viet Cong infrastructure (or Phoenix) machinery moving.

Contact success ratio.

In dispersed, small unit warfare, the success of a unit was largely dependent on the skill with which small units handled each individual contact. If one visualized a contact as a sighting and a success as one or more enemy casualties, the following matrix gives the general idea:

| Contact Success Ratio | Skill Level of Unit |

| 75 percent | Highest skill observed |

| 65 percent | Very professional |

| 50 percent | Unit is beginning to jell |

| 40 percent | Unit has problems but correctible |

| Below 40 percent |

Unit has serious deficiencies in small unit techniques. Probably does many things wrong. |

Night contacts and eliminations.

A unit cannot control the battlefield without effective night operations. It was easy to tell how a unit was doing at night from looking at their statistics. However, if their night results were poor

[213]

it was most difficult to determine why. One approach was to bring in a skillful tactician to observe their operations and determine what the trouble was. For example, one of our units cooled off in heavy jungle at night. After much thrashing around, it was determined by sensors and other means that the enemy had been forced to stop moving at night. This, of course, was good and allowed the unit to ease off at night and thereby generate more daylight effort. Most night problems, however, were failures in basic tactics or technique or poor intelligence appreciation.

Psychological warfare was an area where we wanted very much to improve our performance. We gave it the full treatment hoping to find a handle that would allow us to improve our performance through analysis.

Theoretically, one should be able to develop a matrix between input and output in the form of people who did what the leaflet or broadcast urged them to do. In actual practice, however, this proved impossible to do. There were just too many variables bearing on the system.

Instead of a direct cause-effect relationship between input and output, there was a great spongy glob between them. Sometimes a quick-reaction psychological warfare effort brought immediate results. More often, it achieved no apparent result at all. One .just could not predict or detect the relationship.

What may have blunted the effort was the morale and state of discipline in the targeted units. The Communists, themselves masters of the art of psychological warfare, mounted a rigorous defense campaign against our use of it. Before battle, they told their men that they would be tortured and killed if they surrendered. They forbade their troops to read propaganda leaflets. At all times, they practiced internal surveillance where one was always watching someone and being watched in turn.

Thus, when things were going well and the chain of command was intact, a Communist unit was generally impervious to psychological warfare efforts. Individuals might receive the psychological warfare message but do nothing about it because of fear of punishment of themselves or their families in North Vietnam. However, when a Communist unit was beat up and scattered so the chain of command could not function, individuals, who may have been considering the step for months, would slip away and

[214]

THE INSCRUTABLE EAST

rally. The input-output relation which resulted from these influences was too complex for analysis at field level.

Faced with this impasse, instead of analysis, we relied on a vigorous program broken out in general themes, responsible friendly units, enemy target units and areas. We raised our activity level and insured coverage by this management device. We hoped that the operators would vary the theme and specific content according to the situation in order to get better results. Whenever our intelligence told us a unit was down or beat up, we zeroed in on him and turned up the volume. We stayed with the unit as long as we could fix its location.

One significant observation emerged from our efforts-the more co-ordinated the tactical and psychological warfare effort was on our part, and the more active, the better the overall program. The actual results were difficult to assess, much less measure.

[215]

The pacification program in III Corps was developed to a very high level of overall effectiveness by early 1970. A full discussion of this development is beyond the scope of this paper as it was mainly achieved through conventional management techniques. However, a key element was a thorough analysis of each of the main subprograms to isolate the pacing sub-elements, particularly those which could be measured. By means of standard formats and frequent Government of Vietnam-U.S. combined reviews, these key factors were scrutinized carefully and kept moving ahead. Progress in these key factors appeared to pull the whole pacification program along with them. Of equal importance was frequent cross-coordination with military operations which enabled us to focus the military effort to break key log jams in pacification. Of transcendent importance was the general philosophy that heavy military pressure to bring security was the best way to develop an atmosphere in which pacification really took hold and forged ahead.

The tremendous progress made in Vietnam overall in 1968, 1969, and 1970 was due to defeating the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong remnants militarily, continuing the military pressure to improve security, the development of a governmental structure with vitality, strength and growth potential, all of which made pacification possible. Pacification, in turn, reinforced success in the other areas. The point at which pacification develops its own dynamics could never be determined. However, it seems logical that the development of local forces, particularly police, strengthening of local government and economic and social gains over a long period of time, would forge a structure strong enough to smother or convert local dissidence. Of course, the North Vietnamese strategy was to prevent this by applying military power to arrest or upset progress.

As an aside, the Hamlet Evaluation System has been consistently criticized as a cosmetic device. While one can concede that the absolute meaning of the figures was hard to establish, it is an absolute fact that the Hamlet Evaluation System was an invaluable management tool and a meaningful measure of relative progress. Needless to say, its usefulness varied directly with the knowledge and insight of the user. Most press comment was highly critical. However, such comment tended to be quite biased and uninformed as well.

[216]

Major engineer effort in Vietnam was put on upgrading the major lines of communication. The end result was a good network of paved roads tying together the major population centers and making possible broad economic progress. This work was done mostly by construction engineers and contract civilian effort. Division and some corps engineers normally worked on military roads and other projects which supported combat operations and sometimes extended this major Line of Communication network.

On the other hand, starting years before but increasingly so from 1964 to 1965 and on, the Communists began to "liberate" large areas in Vietnam. The classical method was to blow up all the bridges and cut the local roads, thus making it difficult for the government forces to move and holding the peasants on the land where their rice, labor and sons could be appropriated by the Communists.

In the spring and summer of 1968, we were forced by various considerations to repair an east-west lateral road in Long An Province between National Routes 4 and 5. The enemy at first resisted, was gradually driven away from the road, and eventually decided to live with it. However, in observing the area, it was apparent that the people who had fled the land were returning, normal life was resumed, and pacification moved ahead.

Based on this experience we began a deliberate secondary road program which marshalled all available bits and pieces of engineer effort left over from other key projects. The road construction priorities were worked out to consider all reasonable factors, with the province chief being the final decision-maker.

Although the figures available were rather sketchy, it was estimated that in 1968, 1969 and 1970 we repaired as many roads and bridges in Long An Province as the Communists had destroyed in 1964-68. Expert opinion has it that this road program was an important element in the rapid decline of Communist strength in the province. Aside from the reasons given above, it also seemed to operate by drying up the small local base areas.

An- important element of the program was to design our own criteria and rebuild the most austere road possible which would meet the need. For example, a road which would take bicycles, oxcarts, motorbikes and very small trucks was entirely adequate in many areas as a starter. This "bare bones" approach allowed us to squeeze maximum mileage out of a very modest engineer effort left over from priority projects.

This same approach was tried in Hau Nghia Province with less

[217]

ROAD BUILDING

spectacular results. The reasons are not known-possibly because the farm land was less fertile, possibly because the overall integration of military operations, pacification and infrastructure was less intimate.

Our final conclusion was that the secondary road program was more important to pacification than previously realized. Complete concentration on line of communication upgrading was not necessarily the best solution.

Analysis of Rome Plow Operations

Historically, Rome Plow 2 units were one of our most valuable assets. They performed a very important function in the early days in clearing the flanks of highways. to remove concealment from possible ambush sites. This allowed us to utilize ground lines of communication and got civilian traffic back on the roads. This

[218]

ROME PLOW OPERATION

worked directly against the Communist efforts to isolate the population.

Their second important function was the clearing away of traditional Communist base areas. This denied the enemy the jungle concealment that he had long enjoyed in proximity to vital areas. In III Corps Tactical Zone prior to 1967 the Rome Plow effort had been limited to certain key highways such as QL 13 and QL 1 and massive area cuts in places such as the Iron Triangle, the Ho Bo Woods, the Filhol Plantation, the Bien Hoa-Long Binh complex, and the heart of Binh Duong Province. These were all very useful in the situation that pertained at that time.

We opened 1969 with a highly successful effort to reopen the road from Phuoc Vinh to Song Be. This section of road had been closed for four years because of constant Communist presence in the area. Because of this threat, there was interest in making as wide a cut as possible. In an effort to make our effort more efficient, we conducted a simple analysis of enemy ambushes and determined instead that a 200-meter cut on each side of the road would give good visibility, keep effective rifle fire off the road, and inhibit infantry

[219]

assaults or ambushes. The project was completed at this width and proved to be completely adequate.

As 1969 progressed, aggressive tactical operations wore down the enemy and pushed him back towards his Cambodian base areas. To exploit our success, we pushed teams of Armored Cavalry and Rome Plows out to open the roads in War Zone C which had been abandoned to the enemy for years.

Because of the deteriorating enemy capability and the purely tactical nature of our operations, we elected to further reduce the width of our cuts to 50 meters on each side of the road. This automatically gave us four times the road mileage per day of effort. We found that the resulting 100 meter swath allowed adequate aerial surveillance of the road and did not unacceptably expose vehicles to ambush. Although it allowed the ambusher to get closer to the road, it also narrowed down the observation and exposure zone of the ambush.

Base areas were a more difficult problem. Traditionally, they had been cleared completely. In the case of a large area, this took months of effort. In studying this problem, it was determined that the enemy response to a massive clean cut was to move farther out to the next suitable area and set up for business there. It was, therefore, decided to use a lane clearing technique which would open up the base area for friendly operations but would not automatically drive the enemy out. Initially, a 1,000-meter lane was used with the uncleared interval being left to judgment. If, for example, one diced up the area into 2-kilometer squares of jungle, a 36 percent saving in cutting was achieved. By using a quick and selective cutting technique which bypassed the largest trees and went around difficult areas more rapid cutting was possible and the saving time-wise was greater. As we became familiar with this technique, the lanes were reduced to 500 to 600 meters, thereby increasing the savings.

The most successful use of this technique was in the Trapezoid area south of the Michelin Rubber Plantation and east of the Saigon River. As lane cutting progressed, Sub-Region 1 Headquarters, the 101st North Vietnamese Army Regiment and a coterie of odds and ends evidently decided they would stay in place. As a result, three to four U.S. and South Vietnamese Army battalions were able to decimate them over a period of months by day patrolling and night ambushes. When they finally had to move further away from the populated areas they were so decimated that they could no longer resist or even affect the Government of Vietnam pacification program.

[220]

The key to operations in the III Corps was General Abrams' One War concept, which in simplest terms meant that all military, pacification and governmental resources and activities worked in coordination towards the same goals. Like most powerful ideas it was very simple. Also, like most ideas in Vietnam it was rather difficult in execution.

However, as has been brought out previously, there were various programs and concepts-constant pressure, working on the enemy system, accelerated pacification, Dong Tien-which in themselves facilitated qualitative and quantitative improvement. When these were all stitched together by divisional, provincial and Corps-wide reviews, the overall result was a rather ponderous but fairly effective coordinated effort. Fortunately, the Communists were not very effective themselves and a fairly effective government effort made steady progress.

As one would expect, the conduct of operations at the Corps level was much looser and more diffuse than at the division level.

Although we resorted to considerable fine-tuning (as in the Sub-Region-1 operation), the main energy of the commanders was devoted to crisis management. Whether it would have been possible to have devised a system whereby one kept track of hundreds of enemy units and thousands of friendly units in a systematic and analytical manner is hard to say. The Working Against the Enemy System concept combined with coordinated Regional attacks and the inventory of enemy units-Constant Pressure concept-were efforts in this direction. It should be noted that these three concepts plus an integrated approach to pacification made the Abrams' One War strategy a reality in III Corps. One senses that a red hot review and analysis section with scientist participation and access to a good computer could have systematized many matters which we dealt with in a more informal manner.

One concrete way of stimulating the necessary co-ordination and support was to require all the responsible commanders and officials to keep track of the entire situation-enemy and friendly, military and civilian-with stress on pacification. These rather voluminous statistics, once one became used to using them, gave a clear picture of shortfalls, weak and strong areas, and so forth. It also helped the Vietnamese to get tight control over a complex operation. We are convinced that this approach materially assisted both military

[221]

operations and pacification in the 9th Division and later in the III Corps. Rather than dealing with subjective impressions, the commanders were dealing with cold (fairly reliable) facts.

The Vietnamese Oriental way of looking at things tended to avoid facts. Once the facts were brought out, the Vietnamese approach to a problem tended to be quite logical and decisive. The pitfall here was that the Oriental mind often overlooked the factual, pragmatic approach for various cultural reasons. If one could get them to use hard facts, their effectiveness gained almost automatically.

This integration gimmick illustrates how one could get hold of complex problems by reviewing elaborate statistical formats. This process of statistical review had little overall logic in an analytical sense-it only pointed everyone in the same direction and uncovered log jams. Once the log jams were cleared, forward progress ensued. It was the best way we could make the One War concept really work at all levels.

Whereas one senses we were able to make a sizable dent in analyzing division-level operations, the feeling persists that we only scratched the surface at the corps level. In any case, they both constitute interesting problems for future commanders and staffs.

In spite of the fact that the corps level is more difficult to manage than the division, the combination of the analytic approach, normal command supervision methods, and selected analysis did produce results. As had been mentioned earlier, the exchange ratio of the U.S. units was increased from two to three times (8 : 1 average to 19 : 1 average with a high of 30.1 : 1) . At the same time, the attrition of the enemy by U.S. units (not counting prisoners of war and Hoi Chanhs) was increased appreciably and friendly losses (Killed by Hostile Action and Died of Wounds) decreased markedly. In other words, the U.S. units inflicted 70 percent more damage on the enemy at a casualty cost 56 percent less for an efficiency improvement of 3.8 times. (See Chart 26.) As the South Vietnamese Army units were brought up to strength, re-equipped, and adopted more flexible tactics, their performance improved, but more slowly than the U.S. Chart 26 also illustrates the South Vietnamese Army's steady and encouraging increase in efficiency. The improvements in the performance of all units in III Corps (South Vietnamese Army, Free World Military Allied Forces and U.S.) can be noted in Table 31, All of these units can well be proud of this record as the enemy at the same time was doing his best to evade tactically and was progressively shifting units into sanctuary in Cambodia. As could be expected, pacification proceeded at a rapid rate protected by this

[222]

CHART 26-EXCHANGE RATIOS, III CORPS TACTICAL ZONE, JULY 1968 APRIL 1970

[223]

TABLE 31-III CORPS TACTICAL ZONE SELECTED COMBAT STATISTICS JUL-DEC 68 AND JUL-DEC 69

| Date | Enemy KIA | Friendly KIA | Date | Enemy KIA | Friendly KIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 68 | 1357 | 320 | Jul 69 | 3504 | 424 |

| Aug | 4053 | 766 | Aug | 4965 | 462 |

| Sep | 3442 | 727 | Sep | 4525 | 422 |

| Oct | 2099 | 514 | Oct | 3545 | 299 |

| Nov | 2988 | 743 | Nov | 4821 | 307 |

| Dec | 2602 | 594 | Dec | 4255 | 358 |

| Average | 2757 | 611 | Average | 4269 | 379 |

Exchange Ratio: 4.5 : 1 Exchange Ratio: 11.3 : 1

pressure. The 1st Cavalry Division working with three South Vietnamese Army brigades (regiments) and the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment did a superb job in deep jungle. The 25th Infantry Division essentially worked itself out of a job by driving the 9th Viet Cong Division (actually North Vietnamese Army) into Cambodia. The 1st Infantry Division, in a very quiet sector, by painstaking efforts, was able to achieve a very fine exchange ratio of 55 to 1. (The best division performance seen in a quiet sector.) The 25th South Vietnamese Army Division, under an able commander, was able to work up to a 25 to 1 exchange ratio-a 300 percent improvement.

There are many problem areas remaining which space does not permit listing. But, by late 1969 or early 1970, the nature of the war began to change and the Cambodian operations ushered in, a new phase.

[224]

Endnotes for Chapter X

1 Airborne reconnaissance flights to detect heat emissions from the ground. (click here to go back)

2 The Rome Plow is a big bulldozer with a specialized cutting blade designed to clear heavy brush and jungle vegetation. (click here to go back)

page updated 19 November 2002

Return to the Table of Contents