- Chapter XII:

-

- LAM SON II

(2-5 June 1966)

-

- Operation LAM SON Il

provides a glimpse of some innovations which had nearly as great an

impact on the struggle in Vietnam as the defeat of the enemy by force

of arms. While the enemy must be destroyed or forced to surrender by a

combination of firepower and maneuver, it is pacification which must

end the unrest created by the enemy, improve the lot of the people,

and build a cohesive, viable state. The weapons in this war may be the

healing hands of a surgeon, a bag of rice, a loudspeaker message, or

even toys for children. The 1st Infantry Division used weapons of this

unconventional nature and incorporated psychological warfare in combat

operations.

-

- At 1530 on 2 June 1966, the

first day of a successful hamlet festival in Tan Phuoc Khanh wound

down with all the festivities of a county fair. The steady sound of

the 1st Infantry Division Band had seemed out of place as it marched

through the streets of the small Vietnamese village. It was not just a

concert but a weapon in "the other war."

-

- The seal and search of the

village had started the evening before. While the rest of the division

was preparing night patrols, selecting outpost locations, and digging

in to establish night defensive positions, Major Henry J.

Wereszynski's 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, was conducting an

airmobile assault to set up a cordon around Tan Phuoc Khanh and its

9,000 inhabitants. A combined force of five companies had been formed

to cordon the village. Major Wereszynski had Companies A, B, and C

with Troop A, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, attached and the 7th Company,

7th ARVN Regiment, in support.

-

- LAM SON I1 -a combined

operation conducted by Headquarters, 1st Infantry Division Artillery,

and Headquarters, 5th ARVN Division-had started with a highly

successful hamlet search and "county fair" operation on 26

May 1966 in Binh Chuan village. Because of the wide publicity, the

cordon and seal of Tan Phuoc Khanh had to be completed as quickly as

possible to offset the loss of surprise. The helicopter would be a

valuable tool in providing the necessary speed.

-

- The mission was to pacify the

village, conduct a thorough search, root out the Viet Cong

infrastructure, gather intelligence, and "win

[137]

1st INFANTRY DIVISION BAND

PERFORMING AT TAN PHUOC KHANH-

- the hearts and minds of the

people." Planning and execution involved close teamwork between

U.S. and Vietnamese forces. There was no single commander in charge,

but rather a combined staff of both Vietnamese and U.S. personnel from

the two headquarters was formed.

-

- As the airmobile force was

flying toward its landing zones, Major Wereszynski, in the command and

control ship, was reviewing the plan in his mind, Company A would

assault into a zone north of the village, Company B would be on the

east, and Company C would land in the south. Troop A, 1st Squadron,

4th Cavalry, and 7th Company, 7th ARVN Regiment, were already moving

overland to complete the cordon. As the air assault ended, the ground

elements were moving into position. The village was sealed at 2010

hours on 1 June 1966. Later that night Company A was moved by air

mobile assault farther north to cut off possible Viet Cong escape

routes.

-

- At 0605 hours 2d Company, 7th

ARVN Regiment, moved into the village. Loudspeakers proved to be

extremely valuable in reducing the alarm of the villagers, advising

them what to do, and providing a means of control. While the external

cordon remained in position, 2d Company soldiers established

additional cordon lines to further divide the hamlet into three

sections. Search forces from Binh

[138]

-

WOMAN WINS YORKSHIRE PIG IN

LOTTERY at another

hamlet festival.-

- Duong Province soon followed

and spread throughout the village to begin the search. The force had

been tailored to fit the needs of this operation and contained many

different types of U.S. and Vietnamese units.

-

- The first step was to assemble

all men between the ages of fifteen and forty-five. These men were

moved to the National Police headquarters in Phu Cuong for additional

screening. Next came the real heart of the cordon and search

operation: the hamlet festival. The festival was designed to display

the concern of the Vietnamese government for the welfare of the

people. The start was sounded by the Binh Duong Province band at 0830

hours. By 0900 hamlet residents began arriving in the central area and

were greeted by personnel from province headquarters.

-

- Although not used at Tan Phuoc

Khanh, several tactical units conducted a lottery during county fair

operations. Instructions or information to villagers were distributed

by means of leaflets, which were stamped with lottery numbers. These

leaflets helped control the people and, at the same time, maintain

their interest in the program. The winners received household items as

prizes.

-

- The hamlet festival can best

be compared to a small town's fall carnival with speeches by

candidates who are running for office. To

- [139]

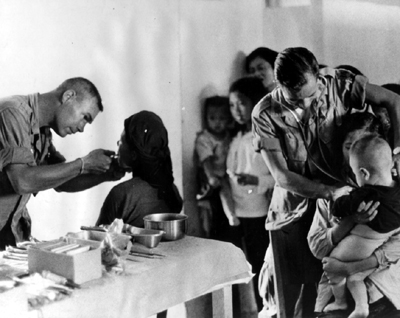

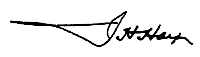

VILLAGERS FROM REFUGEE CAMP

IN BIEN HOA PROVINCE RECEIVE TREATMENT DURING A MEDCAP-

- the children it was all fun

and games. Likewise, the adults found it enjoyable and were

interested to hear about national programs from a government

official. In a war of insurgency, such an operation is the essence

of the fight.

-

- As the people gathered in

the entertainment area, the 5th ARVN Division band began the

Vietnamese national anthem. Coupled with the bright red and yellow

Vietnamese banners and flags, this action conveyed to the people the

presence of a government-one that cared. It was a welcome feeling in

the midst of a protracted war. The national anthem was followed by a

performance of traditional dances and pantomimes by the 5th ARVN

Division cultural teams. Then the province chief, Lieutenant Colonel

Ba, and the district chief, Captain Phuc, explained the government

program to the people and urged them to support the government

cause. Colonel Ba stayed all day talking to elders and heads of

households.

-

- The hamlet festival was a

collection of several functions, The Medical Civic Action Program (MEDCAP)

station was manned by medical personnel from one of the U.S. units.

The staff normally included a doctor, medical specialists,

Vietnamese interpreters, and

[140]

- sometimes a dentist. The

operation was conducted like a "sick call" and held in

conjunction with psychological activities. The medical treatment was

mainly symptomatic-aspirin for pains, soap and medication for skin

diseases, and extraction for toothaches. Serious medical cases were

referred to other facilities outside the military channels for proper

treatment or corrective surgery. The Youth Service Activity

entertained the children so that the parents were free. Games were

played, songs were sung, candy and toys were handed out to the

children, and movies were shown. At one point Colonel Ba joined the

children for a game of ball. The Vietnamese Agricultural Service

provided information to the elders about farming and explained to the

villagers how the government was prepared to assist the farmer. This

service was very popular with the people.

-

- At 1200 an American luncheon

of hot dogs, potato salad, milk, juice, and all the extras was served.

Although the people commented about the strange taste of the food,

they all returned for second and third helpings. The meal was an

interesting change from their normal rice-heavy diet.

-

- The psychological operations

and civil affairs teams performed several duties. They helped direct

and control the people at first and mingled with the crowd, talking to

small groups. They were able to discuss government opportunities and

learn what the citizens needed and wanted from the government. The

real purpose of the hamlet festival was to bring the government to the

people and, at the same time, to turn an intelligence operation into

an activity that the citizens would find pleasant. A major objective

was to eliminate the Viet Cong infrastructure. All civilians were

therefore required to pass through identification stations for an

interview, a check of their identification cards, and the issue of

special passes. This process allowed the detection of false

identification papers and the selection of persons for further

screening. Other stations were established for persons who wanted to

volunteer information. Rice was given to all persons during the

interviews.

-

- By the time the 1st Infantry

Division Band paraded through the streets, the results were becoming

evident. Of the 740 men who had been sent to Phu Cuong for screening

earlier in the day, 29 were found to be Viet Cong suspects, 9 were

army deserters, 4 possessed false identification cards, 13 were former

Viet Cong who had violated the limits of their probation, and 62 were

South Vietnamese draft dodgers. The search of the village had turned

up 25 additional Viet Cong suspects, including 3 women carrying

medical supplies and 10 men hiding in haystacks and wooded areas. The

scout dogs had discovered two tunnels in the village.

-

- During the day 325 individuals

had been interrogated at the identification stations. Two of these

were identified as Viet Cong, one

[141]

- allegedly the Viet Cong

village secretary. A sketch of the U.S. Phu Loi Base Camp was found on

the body of a Viet Cong killed during the assault to establish the

cordon.

-

- The cordon force remained in

position throughout the night, and on 3 June the festival continued.

Selected areas were again searched. The western portion of the village

yielded forty-eight more Viet Cong suspects. They were hiding in

haystacks, tunnels, woodpiles, and watchtowers. By the end of the

second day, the festival had succeeded in softening and changing the

attitudes of many individuals who had been hostile to the government.

The operation was such a success that it was extended for a third day.

By the end of the festivities, the civilian population truly wanted to

assist friendly units in securing their village. One woman was given

200 piasters for volunteering information leading to the apprehension

of a Viet Cong suspect hiding in a coffin. A confirmed Viet Cong led

an intelligence platoon to a weapons cache that also contained Viet

Cong tax collection statistics. He had decided to return to the

government of Vietnam as a result of the hamlet festival. Many

individuals spoke of Viet Cong harassment tactics in the village and

stated that if they had sufficient security many more people would

come there to live.

-

- The cordon and search coupled

with a hamlet festival was truly an innovation in civil affairs and

psychological operations. "The primary accomplishment was the

demonstration of an effective technique to bring government, including

necessary force to initiate law and order°, to a contested hamlet.

Without the cordon and search the operation would have been merely a

festival. Without the festival the operation would have been another

'police action.' Together, the effort (was) a useful means to begin a

pacification drive."

-

- At 0400 hours on 5 June 1966,

the task force was moved a few hundred meters to the north to Hoa Nhut

hamlet for the next operation. A pattern had been established to hit

the Viet Cong at their most vital point their infrastructure.

Information acquired at a later date indicated that the Viet Cong had

reviewed the Tan Phuoc Khanh operation and had estimated that they had

lost 50 percent of their effectiveness. They also figured that two

months would be needed to recoup their losses.

-

- In a country like Vietnam,

where citizens are subjected to the pressures and terrorism of an

insurgent force and where the power and aims of the legitimate

government are questioned and tested each day, any action or incident

that shows the individual citizen that his government is interested

and concerned in his welfare is highly effective. The hamlet festival

served this purpose

well.

-

- In previous experience,

guerrilla forces represented the government that had been displaced by

the invading army. In Vietnam the guerrilla force represented an

external power. Acts of terrorism were

[142]

- directed not at the invading

army but rather at the innocent civilian. All actions were designed to

discredit the existing government and to win the citizens over to the

enemy. This situation changed the whole concept of civil affairs

activities. In the words of Major General Melvin Zais, former

commanding general of the 101st Airborne Division, "a well

organized and managed effective civic action effort is absolutely

essential to the attainment of our aims in Vietnam."

-

- The civil affairs general

staff officer (G-5) became increasingly important to the commander who

was planning operations. In Major General Donn R. Pepke's 4th Infantry

Division, "civil affairs teams [were] employed daily in support

of tactical operations." While the operations general staff

officer (G-3) was making plans for engaging and destroying the enemy

force in an area, the G-5 was planning methods and operations to win

the loyalty and support of the local civilian population. This aspect

was a significant change from World War II, when civil affairs and

civic action were conducted after the hostilities had ended.

-

- A planning and control

organization was obviously needed at brigade and battalion levels to

deal with the problems involving civilians. A temporary arrangement

was made at first, but the experience gained and the lessons learned

early in the 1965 buildup prompted the creation of the civil-military

operations field. This action led to the designation of an S-5, civil

affairs officer, in every separate brigade.

-

- The use of loudspeakers, the

artillery of the civil affairs officer, became a fine art in Vietnam.

The 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) supported ground operations with

loudspeakers borne by helicopters. Divisions issued 1,000-watt

loudspeaker equipment to each brigade and sometimes to battalions. As

a result of this practice, if prisoners were taken or defectors

encountered during tactical operations, the units were able to react

quickly to the opportunity to use these men in developing loudspeaker

appeals to their former comrades. In the 3d Brigade, 82d Airborne

Division, such an appeal was then transmitted by the defector talking

over a PRC-25 radio to a helicopter that rebroadcast the message while

flying over his former unit. Thus the helicopter again demonstrated

its importance in Vietnam by enhancing psychological operations. Major

General Albert E. Milloy, 1st Infantry Division, stated: "Aerial

PSYOP proved most effective when employed in the quick reaction role,

in support of troops in contact, or for immediate exploitation of

ralliers." Psychological operations were also carried on by

frontline troops using bullhorns or hand-held megaphones. Messages

from a newly captured prisoner or a defector were broadcast to enemy

units still fighting. In September 1966 an enemy soldier rallied with

his weapon to a 1st Infantry Division unit and was immediately

interrogated by the G-5. A loud-

[143]

MEMBER OF 8TH PSYOP

BATTALION AND HIS MONTAGNARD LOUDSPEAKER TEAM broadcast

propaganda message.-

- speaker tape was produced in

which the rallier talked about the good treatment he was receiving and

asked former company members, by name, to surrender. Within

twenty-four hours, eighty-eight members of the unit defected.

-

- Leaflets were used

separately or to complement loudspeakers. A multilith press was provided

at the division level for quick reaction. On 13 May 1970 an agent

reported that within Phong Dinh Province some 300 local force Viet Cong

were to be recruited and sent to Cambodia as replacements for North

Vietnamese Army units that had suffered heavy losses. The information

was passed to the U.S. intelligence adviser and the province adviser for

psychological operations. By 1600 on the same day, the psychological

operations staff had prepared a leaflet capitalizing on the raw

intelligence information. The priority target selected for the operation

was the area of Phong Dinh Province, which was known to harbor hard-core

Viet Cong. The province adviser for psychological operations and the S-5

adviser arranged to have the leaflets distributed throughout the

appropriate districts during that night and the next day. Late in the

evening on 14 May, the first Hoi Chanh rallied in Phung Hiep

District with a copy of

- [144]

-

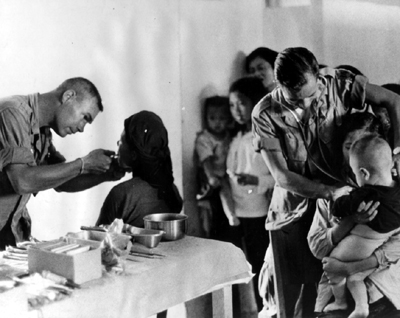

| AVDB-CG |

22 March 1967 |

|

SUBJECT: |

Unsoldierly Conduct of Officers of Cong

Truong 9 |

| TO: |

Commanding General

Cong Truong 9

HT 86500 YK |

| Dear General: |

|

|

-

This is to advise you that during the battle at Ap Bau Bang on 20

March the Regimental Commander of Q763 and his Battalion Commanders

disgraced themselves by performing in an unsoldierly manner.

-

-

During this battle with elements of this Division and attached units

your officers failed to accomplish their mission and left the

battlefield covered with dead and wounded from their units.

-

-

We have buried your dead and taken care of your wounded from this

battle.

|

|

-

Sincerely,

J. H. Hay

Major General, USA

Commanding

|

ONE SIDE OF PERSONALIZED

PROPAGANDA LEAFLET. Other

side carried translation.

-

-

the leaflet in his hand. By 23

May, twenty-eight Viet Cong had rallied, stating that they had done so

because they were afraid of being sent to Cambodia. In a campaign to

attract more ralliers through

- [145]

- personal messages, the 101st

Airborne Division gathered photographs of known Viet Cong operating in

its area of operations. The families were asked to prepare personal

messages to their relatives in the Viet Cong forces. Their messages,

together with the appropriate photograph, were made into leaflets and

dropped in the area where the individual was thought to be operating.

-

- The S-5 of the 2d Brigade, 1st

Infantry Division, developed a "white envelope" concept,

designed to reach soldiers in the Viet Cong forces and the

infrastructure with personalized messages from their families. Each

family with relatives in the Viet Cong forces was given a white

envelope containing a Chieu Hoi (open arms) appeal, rally

instructions, a safe conduct pass, and a letter of amnesty from the

local village or district chief. The intention was that the family

would deliver the material to the Viet Cong member. This technique

directed psychological pressure against both the family and the

individual target.

-

- The success of personal

messages was best described by a Vietnamese who took advantage of this

opportunity.

-

- My family lived under

communist control for more than ten years, and I was forced to work

for the Viet Cong. I was constantly afraid of being hit by American

artillery, and I was seldom allowed to see my wife, even though I was

a local guerrilla.

-

- Then I found a Chieu Hot' pass

dropped by an American helicopter. My wife and some friends told me

that it would be good to be a Hoi Chanh [a person who has

rallied], but I hesitated for many weeks.

- One day I came back from an

operation to find that my wife had taken our children to Lam Son, out

of VC reach. So, with the pass sewed to the lining of my shirt, I

waited for my chance to escape NVA control, and turned myself over to

the GI's.

-

- Since then I have been trained

to do scout work. I can see my wife and children every week, and am

happy working with the 1st Division soldiers.

-

- Several innovations were

introduced to assist the interpreter at the lowest level frontline

unit. Bilingual questionnaires were prepared which enabled commanders

to gather intelligence and develop appeals quickly for psychological

purposes. In March 1970 another infantry division initiated the idea

of a bullhorn booklet to aid in the production of rapid-reaction

messages. The booklet contained twenty-four printed messages, varying

from appeals to warnings about restricted areas. The tactical units

could select an appropriate message and have a Vietnamese broadcast it

immediately. Other units used multilingual tapes. The 1st Infantry

Division obtained excellent results from trilingual tapes, which were

based on the ethnic background of civilians in an area.

-

- The greatest innovation made

in the G-5 area during the course of the Vietnam War was the increase

in importance of psychological operations, civil affairs, civic

action, and populace and resources con-

- [146]

- trol. Whereas before, G-5

activities had been viewed as supporting an operation after the fighting

had ended, they were now integrated into the combat operation plan

itself. Commanders and staff officers at battalion, brigade, and

division levels learned that combat operations ultimately supported

pacification, not vice versa.

-

[147]

- page created 15 December 2001

-