- Chapter XIII:

-

- Cu Chi

-

- Vietnam was a different war.

It was a conflict where the front line was not a trace on a map but

was rather wherever the opposing combat forces met and fought. The

secure rear areas of past wars that were so necessary for support were

nonexistent in Vietnam. Only the areas that a commander actively

secured could be used for support activities. This situation resulted

in the base camp. The same security problem required convoy operations

in a hostile environment, and better ways to conduct such operations

had to be found. New techniques in automatic data processing were

developed so that the machines could be used to support tactical

activities. Finally, the widespread use of Army aircraft led to new

and more efficient methods of maintaining the planes and helicopters.

-

- The quiet of the 25th Infantry

Division base camp at Cu Chi was shattered by explosions from incoming

rocket rounds exactly one hour after midnight on 9 May 1968. Thirty

rounds of 122-mm. and 107-mm. rockets, fired without warning from the

surrounding area, rained down on the U.S. camp. The officer on duty at

the 2d Brigade tactical operations center needed no confirmation from

the bunker line as he switched on the base sirens and announced

Condition RED. Forces on the perimeter were doubled, staffs of major

units raced from their tactical operations centers, and troop units

were readied to move to secondary defense positions. Word went out to

a nearby fire support base, the local ARVN headquarters, and II Field

Force headquarters that the base camp was under attack.

-

- Two Cobra helicopters from

Troop D, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, in the air soon after the last

rocket fell, radioed base camp defense and the artillery net. By this

time the direction of the attack had been estimated, and previously

positioned defense artillery had been fired. The two gunships searched

the suspected enemy launch area and adjusted U.S. artillery

accordingly.

-

- As the battle quieted down,

each sector of the bunker line called in to report all clear. An ARVN

patrol in Vinh Cu, just south of the base, had had no contact. Nearby

fire support bases, the Cu Chi subsector headquarters, and the units

at Phu Cong and Ba Bep bridges reported that all was quiet. In two

hours the camp commander de-

[148]

- cided that no ground attack

was coming, and word went out to go to Condition YELLOW and finally,

at 0300, to return to Condition WHITE.

-

- The incident was another

standoff attack.

-

- Intelligence had forecast no

high point of enemy activity, and there had been no indication of

such. The rockets might even have been fired from unattended and

locally fabricated launchers. According to a captured enemy rocket

company commander:

-

- U.S. forces in Vietnam are

disposed in large fixed installations which always provide our forces

with lucrative targets. Our forces are always certain that as long as

the weapons hit the installation, the U.S. forces will lose equipment

and manpower. Likewise, these large posts do not have sufficient

forces to control the surrounding countryside, which makes our attacks

easier.

-

- The G-3, operations general

staff officer, ordered a reconnaissance in force in the suspected

launch area the next morning; everybody not on duty at the perimeter

or in the various support units and headquarters went back to sleep.

By noon, two slightly wounded mechanics were back on duty, and a

battered five-kilowatt generator was hauled to the salvage yard. (The

above story is a composite account of an actual attack on Cu Chi and

typical results and reactions by the division.)

-

- These standoff attacks were

designed to destroy allied military assets and weaken morale at

minimum risk to the enemy. Moreover, they demonstrated the enemy's

ability to attack and inflict damage on major U. S. and Republic of

Vietnam installations at a time and place of his own choosing. The

propaganda value was high, and at times the damage was significant. A

considerable part of U.S. military resources was used to protect these

fixed installations.

-

- Cu Chi was surrounded by a

large cleared area, including a manmade lake backed up by Ann Margaret

Dam, which was built by Lieutenant Colonel Edward C. Gibson's 65th

Engineer Battalion. The bunker line consisted of observation towers,

firing positions with overhead cover, an earth berm, barbed wire

entanglements, spotlights, and minefields. The support battalions

camped at Cu Chi were assigned sectors of the defensive perimeter with

very specific, rehearsed plans for reinforcement and counterattack.

Artillery, countermortar fire, sensors, communications,

reconnaissance, combat patrols, air support, and pacification all

worked together to permit a large logistic and command complex to

survive in no man's land.

-

- In Vietnam, the base camp was

a place where the individual soldier could train, take care of his

equipment, and get some rest and relaxation. It also provided a

full-time home for the larger tactical headquarters and the support

units. The reason for developing such a facility was given by General

William C. Westmoreland:

- [149]

- Because of the nature of the

war, tactical units had to be scattered throughout the nation at

widespread locations. The lack of a sophisticated transportation

system necessitated major units establishing their own logistic bases

rather than one central depot serving a number of units . . .

-

- No activity could survive

unless it was protected against ground attack and tied into the

network of combat support. Supplies, maintenance facilities, hospitals

and rest centers, airfields, administrative offices, and artillery

were all located within bases to protect them against the enemy's

assassination squads, local forces, standoff attacks, sappers, and

main force units.

-

- Being a semipermanent and

vital installation, Cu Chi was selected with an eye to water supply,

drainage, vegetation, and soil composition. Enough land was acquired

to allow expansion of the camp and adequate fields of fire. Like many

such camps, Cu Chi was situated close enough to a local civilian

community to require constant attention to the perimeter's defense.

Finally, supply routes around Cu Chi were such that a base camp could

also be developed and supported administratively and logistically. As

one brigade commander summed it up, "The guiding principle is to

conduct the business of the base camp so that it supports the maximum

of the brigade's needs and detracts the minimum from the brigade's

tactical operations."

-

- The 25th Division's planning

in preparation for the construction of Cu Chi was unique. At their

vantage point in Hawaii, division personnel received large-scale map

coverage of the future division area from the United States Army

Pacific Mapping and Intelligence Center. These maps enabled the

planners to select and analyze a base camp site. After the division's

advance party arrived in Vietnam and inspected the site, the base

development plans were put into final form. The assistant division

commander for support, Brigadier General Edward H. de Saussure, headed

a base camp development committee that included in its membership the

chief of staff, the G-4 (assistant chief of staff for logistics), the

division engineer, the division signal officer, and representatives

from the major units that would be occupying the camp. The clearing of

fields of fire and the construction of bunkers and wire barriers had

first priority. The various battalion cantonment areas were selected,

and the road and telephone line networks were designed and approved.

Before the division left Hawaii, it obtained precut tent and latrine

kits. The kits were assembled by each unit in the division, packaged

or banded, and shipped with unit cargo to Vietnam. At the site, these

tent frames and latrines were easily erected in the designated unit

areas and "added immeasurably in establishing the living areas

prior to the arrival of the monsoon season." Within a relatively

short time after the division arrived at the Cu Chi base, work began

on semipermanent buildings.

-

- To improve base camp living

conditions without waiting for an

[150]

- overworked supply system to

function, the division had left for Vietnam with ice machine plants,

65-cubic-foot walk-in refrigerators, 10kilowatt generator sets, ice

chests, and folding cots. Also taken along were filing cabinets,

desks, chairs, tables, safes, tools, tentage, and communications

equipment that came under the general heading of "post, camp, and

station" property. Improvements in facilities and living

conditions at Cu Chi progressed steadily. Maintenance shelters, fuel

storage areas, ammunition bunkers, roads, and hardstands were built.

Much of the construction was regulated by formal stateside procedures,

and a great deal was done on a self-help basis because there were not

enough engineers to go around. In the hot wet climate, SEA (Southeast

Asia) huts were far cheaper and better than tents for semipermanent

use. As these wooden huts were erected, Cu Chi took on the look of a

real city.

-

- Post engineer functions were

performed under a contract administered by the Army headquarters at

Long Binh. The contractor provided central power, certain building and

ground maintenance, fire protection, and supervision of a variety of

hired-labor jobs.

-

- Although living conditions

were austere, the fixed bases allowed a permanence undreamt of in

World War II and Korea. The costs of operations to enhance morale were

insignificant in comparison with their value. A large PX served the

residents of the camp and frequently the fire bases and the troops in

the field. Cu Chi had virtually all of the facilities found at

permanent military installations outside Vietnam. The list included

small clubs for officers, noncommissioned officers, and enlisted men;

a USO club; barber shops; a MARS (Military Affiliate Radio System)

station; a Red Cross field office and clubmobile unit; sports fields;

miniature golf courses; swimming pools; and chapels. These troop

support facilities, the occasional respites for the fighting units at

division "Holiday Inns," the outstanding medical service,

the one-year tour, and the rest and recuperation program contributed

to the virtual elimination of incapacitating combat fatigue. More than

1,000 men a month left Cu Chi for five-day holidays in Hong Kong,

Bangkok, Tokyo, Manila, Singapore, Penang, Taipei, Australia, or

Hawaii. Additional rest and recuperation facilities were available at

the beach resort in Vang Tau.

-

- The base camp, at times,

caused considerable consternation to the combat commanders. It tended

to devour their combat resources and become "the tail that wagged

the dog," At Cu Chi the 2d Brigade commander was usually

appointed to run the camp, and he named a full-time deputy to

supervise the administrative details of camp operation, base camp

defense, and personnel overhead. All commanders found that

"semipermanent base camps require manpower, equipment, and

services beyond the organic capabilities of battalions, brigades, and

divisions." By 1968 the Department of the Army had

[151]

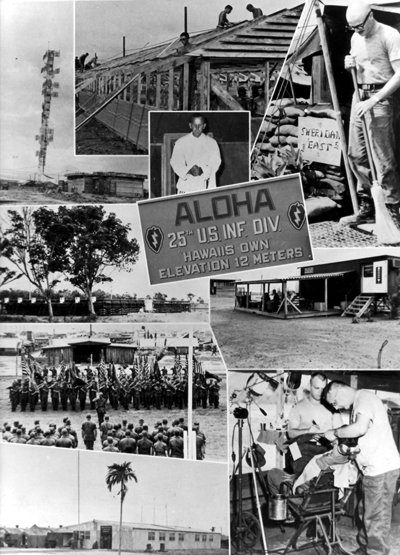

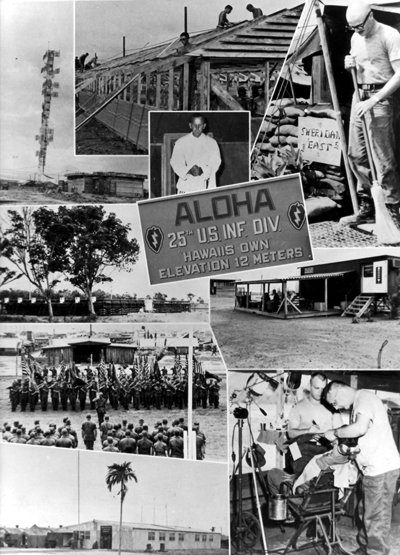

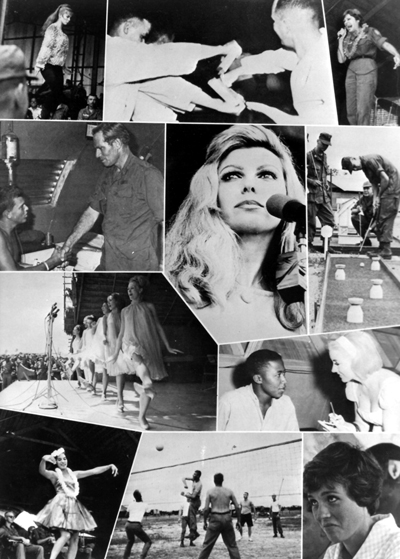

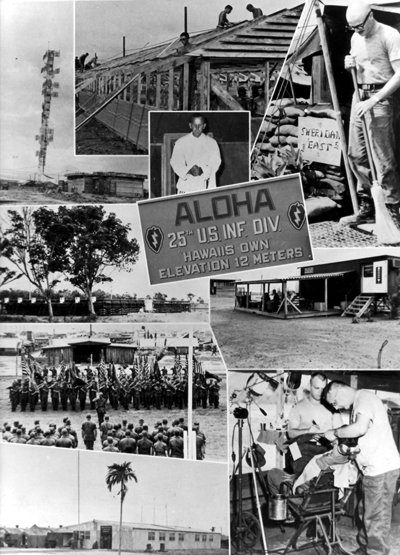

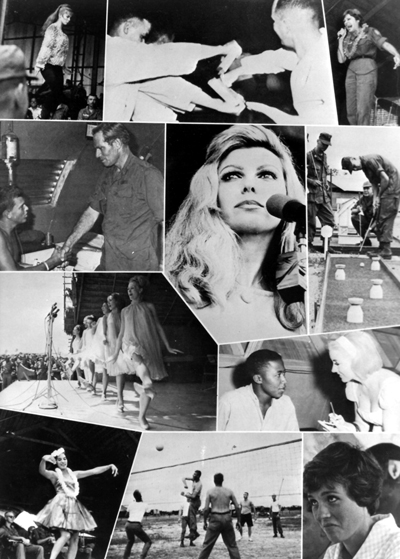

SCENES AROUND CU CHI

BASE CAMP-

- approved a personnel increase

for base camps. This measure was a great help to the commander.

The camp at Cu Chi and the two other base camps in the division at

one time had an augmentation of ap-

[152]

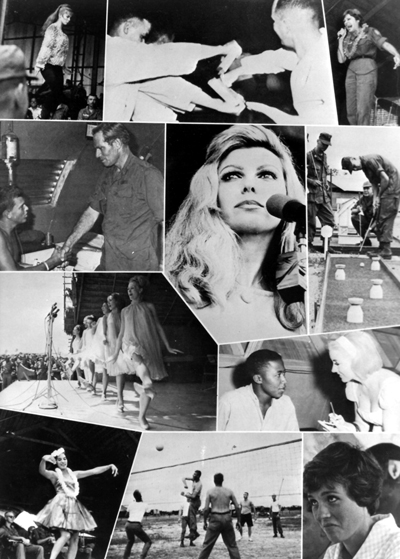

SPECIAL SERVICES

ACTIVITIES AT CU CHI BASE CAMP-

- proximately 500 officers and

enlisted men. This number was trimmed to around 100 by early 1969.

-

- Generally, logistic support at

base camps came from divisional and nondivisional units. As a rule the

25th Infantry Division Support

[153]

- Command (DISCOM) provided

supply and maintenance support for nearby tactical operations direct

from Cu Chi and the two other division base camps, Tay Ninh and Dau

Tieng. The support command sent along forward support elements for

operations farther away and also supplied all of the various landing

zones, fire support bases, and other tactical unit locations. Forward

support activities and logistic support activities from the 1st

Logistical Command provided additional support. A forward support

activity was a provisional organization set up in the vicinity of the

forward operating base of a tactical unit. As described in one report:

"It is deployed to support a specific tactical operation when the

tactical organic support capability is not sufficient to provide the

support required." By contrast the logistic support activity was

a "continuing activity, generally located in a fixed base camp to

provide direct and general supply, maintenance, and service support to

US and FWMAF (Free World Military Assistance Forces) on an area

basis." By way of illustration, the 29th General Support Group of

the Saigon Support Command was the major nondivisional unit charged

with "across-the-board" logistic support in the 25th

Infantry Division's tactical area of responsibility. The 29th General

Support Group set up forward support areas for the 25th Division on

such operations as MANHATTAN and YELLOWSTONE. Although the 29th did

not establish a logistic support activity as such at Cu Chi,

subordinate units of the group were based there and furnished direct

and general support supply and maintenance and certain services to the

division base camp. A logistic support activity was, organized at the

Tay Ninh base camp in support of the 1st Brigade and other tenant

units.

-

- The primary means of

resupplying Cu Chi and the other base camps in the area of the 25th

Infantry Division was by road. The 25th Supply and Transport Battalion

and the 1st Logistical Command ran an average of four convoys,

totaling 268 vehicles, a day on the highway between Cu Chi and the

supply complex in the Long Binh Saigon area. Division supply routes

varied, from those strictly in enemy territory to those that were

fairly safe for allied forces during daylight hours. In contested

areas, major military operations were conducted to open roads to

convoy traffic. Usually, effective convoy operations were possible

only because of the mutually supporting artillery fire support bases

along the route. Patrols, ambushes, and local search and destroy

operations were conducted near the road. These techniques allowed

convoys to travel with minimum escort. If the situation warranted,

permanent outposts were provided to secure critical bridges and

defiles. These outposts patrolled the road to prevent mining and

ambushing.

-

- In August 1968 the 25th

Division developed new, aggressive convoy procedures to reduce losses.

The convoys were divided into smaller,

[154]

- self-sufficient march units.

Ammunition and fuel vehicles were placed at the rear to prevent an

entire convoy from being blocked by burning vehicles, and wreckers and

spare tractors were added to keep traffic moving. Military police

elements provided control. A major innovation was having the convoy

commander airborne over each convoy, from where he directed all march

units and security forces. Armored vehicles were outposted at critical

points along the route rather than moving with the convoy, as had been

the practice. Gunship cover was arranged ahead of time over potential

ambush sites. In areas where the road passed through jungles and

plantations, Rome plows were used to clear potential ambush sites well

back from both sides.

-

- In the fall of 1968, a convoy

operating under the revised procedures began to assemble. Unknown to

the men, the enemy was preparing an ambush in a rubber plantation

seventeen kilometers to the north. This attack was to be the first

test of the new procedures. Before the convoy moved out, the area

commanders flew over the most likely ambush sites. Combat elements

were positioned at several possible sites, and the route was swept for

mines and booby traps.

-

- The last stretch of road over

which the convoy was to pass was flanked by relatively flat terrain

where a rubber plantation had recently been cleared of vegetation. The

first and half of the second march units had entered the plantation

when mortar rounds began falling all around them. Recoilless rifles,

rocket-propelled grenades, and automatic weapons were fired at the

convoy from both sides of the road. The training and orientation of

convoy personnel quickly paid off. Vehicles short of the ambush halted

and organized local security. Drivers moved damaged vehicles off the

roadway, allowing other vehicles in the killing zone to continue to

their destination.

- The enemy force was

immediately engaged by the convoy's security elements. Previously

positioned reaction forces moved against the enemy's rear while

preplanned artillery fire, gunships, and tactical air strikes took

their toll. When the battle was over, the division counted

seventy-three enemy dead and had captured large quantities of weapons

and equipment. Allied losses were light. The enemy ambushers were

soundly defeated.

- In the following months the

enemy attacked several more convoys. In every instance he failed to

halt the fleeting target because he was overwhelmed by a massive U.S.

reaction. The division had turned a defensive situation into a highly

profitable offensive maneuver.

-

- The use of convoy operations

as a tool of pacification was a unique innovation. In the 25th

Division the convoy was often used even when aerial resupply would

have been easier. The reason for this maneuver was to open and expand

the road network to strengthen friendly forces in the area. As soon as

it became relatively safe for military

[155]

- convoys, civilian commercial

vehicles could also use the route. This action had a direct and often

phenomenal influence on the South Vietnamese people; they flowed back

into the area, repaired their homes, and began to farm the

countryside.

-

- The electronic computer as an

increasingly effective management tool was introduced into the combat

headquarters in Vietnam. The Field Artillery Data Computer, already

familiar to the artilleryman, the UNIVAC 1005, and the NCR (National

Cash Register) 500 were used by the Tropic Lightning Division for

routine artillery fire and survey programs and administrative

management; and they were ultimately used to assist the commander in

making decisions. Automatic data processors at Cu Chi became involved

in providing information to many elements within the division as well

as to command elements in Vietnam, Hawaii, and the United States. They

used standardized Army data systems that interfaced with command and

support elements external to the division and with programs developed

by their own personnel for the support of division elements.

-

- The standard systems provided

support in the areas of personnel, finance, and logistics. The

standard Personnel Management and Accounting Card Processor (PERMACAP)

system linked the division with ASMIS (A)-Major Army Subordinate

Command Management Information System (Armywide personnel reporting

system)-to provide information on the individual 25th Division soldier

through channels to the Pentagon. It also produced recurring reports

and rosters for personnel management within the division. The programs

and procedures for the system were developed and maintained by the

U.S. Army Computer System Command (USACSC). The UNIVAC 1005 computer

equipment was mounted in mobile expansible vans parked outside the

division's tactical operations center. The PERMACAP system provided

timely and accurate data, reduced clerical effort, and eliminated

duplication in the personnel support area.

-

- Another standard Army system

used at Cu Chi was the direct support unit-general support unit (DSU-GSU)

system operated by the 725th Maintenance Battalion. This system

provided stock control and inventory accounting for repair parts. The

same programs and equipment are used by Army personnel at 150

installations in the United States and five foreign countries. The

DSU-GSU system uses an NCR 500 computer and a variety of components

from other manufacturers. On 29 October 1966 the 25th Division

received its system, which soon began to provide timely, complete, and

accurate spare parts handling as well as increased management reports

to commanders. The system also fed data to higher headquarters and, in

turn, to supply depots in the continental United States.

-

- The standard system used to

pay the soldiers of the 25th Division was called Military Pay,

Vietnam. It was developed by the U.S. Army

[156]

- Finance and Comptroller

Information Systems Command and used the UNIVAC 1005 computer.

-

- The 25th Division started

early in the war to develop many uses for its automatic data

processing equipment in support of operational planning. By 1970,

Major General Harris W. Hollis had concluded:

-

- In no other war have we been

so deluged by so many tidbits of information for we have been

accustomed to an orderliness associated with established battle lines.

Here, though, we have had to make our decisions based not upon enemy

regimental courses of action, but rather upon the numerous isolated

communist squad-sized elements. So with the scale down of the level of

operations, we have had to increase our reliance on objective analysis

of logical courses of action.

-

- The computer reduced the time

required to analyze and interpret information. The commanders obtained

a better picture of the enemy and were able to exploit valuable

information quickly. At Cu Chi all the input for computer analysis was

taken from existing reports, and with the computer working on a

24-hour schedule, no significant interference with other activities

occurred. A typical application was the use of the UNIVAC 1005 to

analyze the threat from deadly mines and booby traps in the division

area.

-

- The maneuver unit operation

summary program analyzed the date and times of combat operations, size

and type of operations, type of support provided, and, most important,

results obtained in each case. The program identified the most

successful type of operation in each of the twenty-six subdivisions of

the area of operations. A major by-product of the program was an

indication of changes in enemy tactics soon after they occurred.

- The enemy base camp denial

program used dates and time, unit size and designation, type of

terrain, co-ordinates, type of operation, fire support, and results of

contacts. It indicated which types of operations were most successful

in each enemy base camp area. It provided records of these operations

and indicated which areas would most likely contain significant enemy

forces. As a result, scheduling and planning of operations in enemy

base camp areas improved.

-

- The UNIVAC 1005 was also used

as a file update and printing device, with little computing being

done. Lists of known and suspected Viet Cong were updated and printed

on a recurring basis to provide a ready source of current

intelligence. This form of automation permitted simultaneous and

timely use of division intelligence by several elements of the

division in various operational areas and allowed for rapid updating

of information to be passed to other headquarters.

-

- In addition to its own computer

effort, the 25th Infantry Division took advantage of many outside

computer operations. A typical example was the division's use of

the computer-generated MACV Hamlet Evaluation System.

[157]

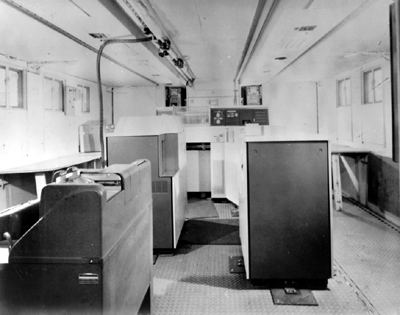

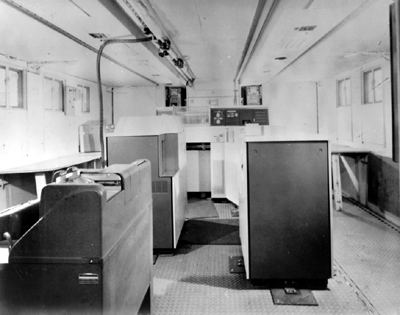

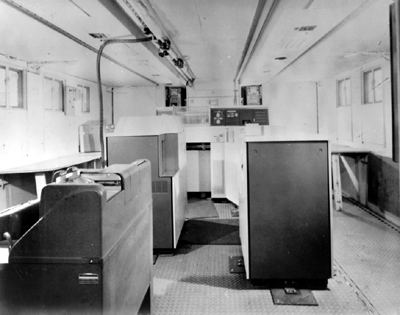

INTERIOR OF UNIVAC 1005

COMPUTER VAN

-

- Another major activity at Cu

Chi was the intensive Army aircraft maintenance program. All divisions

in Vietnam required this massive effort, and each division base camp

devoted a major portion of its area and resources to aircraft

maintenance. Lieutenant General Julian J. Ewell in his debriefing

report wrote:

-

- Aircraft maintenance is the

most important single area in the division, due to the fact that the

tempo of operations is dependent to a large degree on a high aircraft

availability rate. With a fixed base system as in Vietnam, one can

optimize the aircraft maintenance system (hangars, hardstands, lights,

etc.) and achieve peacetime availability rates under combat

conditions. We flew the fleet 90 hours per month per aircraft (and

were edging up to 100 hours) and kept the availability rate over 80 %

. Hueys and Cobras could be kept up in the high 80's. This required a

virtuoso maintenance performance with iron control over every aspect

of both aircraft operations and maintenance.

-

- The aircraft maintenance

program in Vietnam started at the top with the 34th General Support

Aviation Maintenance and Supply Group, which provided limited

depot-level maintenance, general support, backup direct support

maintenance, and supply support for all Army aircraft in Vietnam.

Support was also given for airframe,

[158]

- power-plant, armament, and

avionics repair. From early 1965 the 34th General Support Aviation

Maintenance and Supply Group grew to four aircraft maintenance and

supply battalions with a total of ten direct support and five general

support companies, because the number of aircraft increased from 660

in 1965 to over 4,000 in late 1968. Backup maintenance was given to

both the division maintenance units and the 1st Aviation Brigade. The

brigade, in turn, provided supplemental logistic and tactical airlift

throughout Vietnam.

-

- Concepts relative to Army

aviation in land warfare had never been thoroughly tested in combat;

therefore, Vietnam was something of a laboratory for the discovery and

development of many innovations in aviation operations. As a report by

the Pacific Command on the war in Vietnam states:

-

- Several actions were taken to

speed maintenance and repair procedures. Direct support maintenance

detachments were provided to all separate helicopter companies. This

additional maintenance capability was immediately reflected by a

corresponding rise in aircraft availability rates.

-

- Initially, direct support

aircraft maintenance detachments were attached to nondivisional

aviation units. Next, many detachments were completely consolidated

with the service platoon of the parent aviation company, allowing

better use of supervisory personnel. Responsiveness to the aviation

unit's over-all flying mission was greatly increased. Studies made in

1966 revealed that for divisional units the number of aircraft

available had risen approximately 15 percent. The studies also showed

that the maintenance system of the separate aviation units was capable

of more complete direct support maintenance than was the conventional

divisional maintenance system. The nondivisional units provided, in

effect, a one-step maintenance system by integrating organizational

and direct support aircraft, avionics, and armament maintenance

efforts. A study by the Army Concept Team in Vietnam recommended

approval of decentralized direct support aircraft maintenance for all

standard infantry divisions in Vietnam. Major General George 1.

Forsythe in his debriefing report wrote, "Sufficient advantages

accrue from the decentralized maintenance concept to warrant

implementation at the earliest practical time."

-

- The recovery of disabled

aircraft was another mission performed daily by aircraft maintenance

units in Vietnam. The 56th Aircraft Direct Support Maintenance Company

recovered over 350 downed aircraft in 1968 alone. The former commander

of the 56th, Lieutenant Colonel Emmett F. Knight, tells how

"Goodnature Six" and many other direct support units

accomplished the mission of recovery.

-

- The aircraft recovery team is

organized around the UH-1H. It is the rigging ship and carries the

team, tools and equipment required to prepare a downed aircraft for

airlift. The rigging ship provides weapons for fire support while on

the ground and the necessary radios to control the operation.

[159]

RECOVERY OF DOWNED

HELICOPTER BY CH-47 CHINOOK-

- A normal mission might begin

with a radio or phone call to the Direct Support Company's operation

officer. This request includes all necessary information: type of

aircraft, location, extent of damage, security situation, etc. The recovery officer (airlift commander) is notified immediately and

begins his planning. He makes a thorough map reconnaissance, does

some rapid time-distance planning and places a call to the unit

supplying the CH-47 (Chinook). He will pass the mission, including time

on station which he has calculated, to the Chinook unit control station.

[160]

- Meanwhile, the copilot of the

rigging ship will have the recovery ship wound up. Takeoff is

initiated within minutes after the mission is received . The

flight plan is opened and radar monitoring is requested. Artillery

advice is checked periodically along the route.

-

- As the flight progresses into

the area where the downed aircraft is located, contact is made with

the ground forces operating in the area. The troops at the site report

on the exact situation as final approach is initiated.

- On the ground the rigging crew

from the UH-1H begins preparing the downed aircraft for the imminent

pickup by the CH-47 which should arrive on the scene momentarily. The

pilot of the Chinook receives advice and assistance from the recovery

officer while on approach, as the rigging crew completes the hook-up,

and during departure from the area, All elements are then notified

that the extraction has been completed.

-

- Nearly every aircraft which

crashes, is shot down or forced to land in enemy controlled or

contested territory will be recovered for repair or salvage. The

effort will be coordinated by the aircraft maintenance direct support

unit.

-

- Between 1965 and 1971, the

CH-47 (Chinook) rescued downed aircraft worth approximately $2.7

billion.

- A related innovation which

helped to sustain the number of division aircraft available was the

development and use of a floating aircraft maintenance facility. This

facility was a Navy seaplane tender converted into a floating depot

for aircraft maintenance. The ship, the USNS Corpus Christi Bay,

arrived on station in Vietnam on 1 April 1966. By July production

reached 34,000 man-hours per month of manufacturing, disassembling,

repairing, and rebuilding operations. During fiscal year 1969, a total

of 37,887 components valued at $51.9 million was processed. Ninety-one

percent were returned to serviceable condition. The 34th General

Support Group reports indicate that the floating aircraft maintenance

facility alone was responsible for an additional 120 aircraft

available daily in Vietnam.

-

- In the final analysis, the

base camp and its many facilities were many things to many people. It

was a "Holiday Inn" to the soldier in the field and a base

of operations for the logisticians. It represented a drain on

resources of the combat commander, but it permitted the aircraft

mechanic to do his job. It was a phenomenon of the area war.[161]

- page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents