- Chapter II:

-

- Ia Drang

-

(October-November 1965)

The battle of Ia Drang

illustrates the influence of the helicopter on combat operations. It also

demonstrates the usefulness of new organizations such as the air cavalry,

with its greatly increased ability to locate and fight the enemy, and the

airmobile division, with its great advance in mobility. The expanded role

of Army aircraft is seen in such refinements as the use of the gunship and

the tactical employment of airmobile troops. The battle story introduces a

series of innovations developed before and during the Vietnam War.

-

- There has been some speculation as

to how the war would have been waged without the helicopter. General Westmoreland

answered the question in this way:

-

- Suppose that we did not have helicopters

and airmobile divisions today. How many troops would we have needed to accomplish

what we have achieved in South Vietnam? . . . No finite answer is possible

because our tactics in Vietnam were based on massive use of helicopters ....

What would we do without helicopters? We would be fighting a different war,

for a smaller area, at a greater cost, with less effectiveness. We might as

well-have asked: "What would General Patton have done without his tanks?"

-

- The helicopter was first used in combat

by U.S. armed forces for medical evacuation during the Korean War. Although

many helicopter assault techniques were later developed by the U.S. Army and

Marine Corps, it was the findings of the Howze Board, the formation of the

11th Air Assault Division, and the development of small turbine engines that

first brought airmobility into its own.

-

- The first airmobile division was sent

to Vietnam in the third quarter of 1965 as the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile).

After establishing a base at An Khe in the II Corps Tactical Zone and conducting

a few operations against local Viet Cong forces, the division showed its strength

in the la Drang Valley in the fall of 1965.

- On 19 October the enemy attacked a

Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camp at Plei Me-the opening bid in

an attempt to take over the Central Highlands. By 22 October intelligence

indicated that there were two North Vietnamese Army regiments in the area:

the 33d Regiment, at Plei Me, and the 32d Regiment, which was waiting in ambush

to destroy the expected relief column from Pleiku, north of Plei Me.

- [10]

- The Vietnamese 11 Corps commander

was confronted with a difficult choice. He could refuse to go to the relief

of Plei Me and lose the camp, or he could commit the reserve from Pleiku,

stripping the area of defensive troops. If he lost the reserve, Pleiku would

be easy prey. for the Communists, who could then control the western part

of the Central Highlands. He decided to ask for help from the U.S. forces.

The Commanding General, Field Forces, Vietnam, Major General Stanley R. Larsen,

sent the following message to Major General Harry W. O. Kinnard, Commanding

General, 1st Cavalry Division:- "Commencing first light 23 October First

Air Cav deploys one Bn TF minimum 1 Inf Bn and 1 Arty Btry to PLEIKU, mission

be prepared to assist in defense of key US/ARVN installations vic PLEIKU or

reinforce 11 Corps operations to relieve PLEI ME CIDG CAMP."

-

- Task Force INGRAM was airlifted from An Khe

to Pleiku early on 23 October. The force consisted of the 2d Battalion, 12th

Cavalry, reinforced with a battery of artillery. While the move was under

way, the division commander, sensing that a decisive operation was imminent

at Plei Me, obtained permission to deploy the 1st Brigade to Pleiku. The brigade

headquarters with the 2d Battalion, 8th Cavalry, and two batteries of the

2d Battalion, 19th Artillery, arrived by air at Camp Holloway by midnight

on 23 October to assume operational control of Task Force INGRAM. The 1st

Brigade was charged with securing Pleiku, providing artillery support for

the Vietnamese Army's relief of Plei Me, and furnishing a reserve force.

- Meanwhile, the ARVN (Army of the Republic

of Vietnam) armored relief column began moving down Provincial Road 6C toward

Plei Me. At 1730 hours the North Vietnamese Army struck the relief column

at two points, but 1st Cavalry artillery was called in on the ambushing enemy

with deadly accuracy and was a decisive factor in repulsing the attack.

-

- Before the relief column arrived at

Plei Me, the camp had been resupplied day and night by airdrops from the Army's

CV-2 (Caribou) of the 92d Aviation Company, the CV-7 (Buffalo) of the U.S.

Army Aviation Test Board, and the Air Force's C-123. On the night of 24 October

the weather was overcast and the camp could not be seen from the air. In order

to identify a release point on which to drop the parachute loads, the camp

commander fired a star-burst flare straight up through the overcast, and the

pilots released their loads using the flare as a reference point. Most of

the ammunition and food landed within the compound.

-

- On the evening of 25 October the relief

column arrived at the camp, which was still under siege, and immediately reinforced

the defensive perimeter. By then, 1st Cavalry infantry and artillery had air

assaulted from Pleiku into landing zones within close support range. The original

enemy plan to destroy the ARVN relief column and then

- [11]

- fall on Plei Me had failed. At 2220

hours on 25 October, the 33d North Vietnamese Army Regiment at Plei

Me was ordered to withdraw to the west, leaving behind a reinforced battalion

to cover the withdrawal.

-

- At this point General William C. Westmoreland

visited the 1st Brigade's forward command post and directed the 1st Cavalry

Division to pursue and destroy the enemy. The division's scope of operations

changed from reinforcement and reaction to unlimited offense. The division

was to be responsible for searching out and destroying all enemy forces that

threatened the Central Highlands. The 1st Brigade pursued the battle through

9 November. The 3d Brigade took over until 20 November, when the 2d Brigade

began the final operation.

-

- The battlefield covered 1, 500 square

miles of generally flat to rolling terrain drained by an extensive network

of rivers and small streams flowing to the west and southwest across the border

into Cambodia. The dominating feature of the terrain was the Chu Pong massif

in the southwestern corner of the area, straddling the Cambodian-Vietnamese

frontier. For long periods this mountain mass had been an important enemy

infiltration area and one of the many strongholds where enemy forces could

mass and construct strong defenses under the heavily canopied jungle.

-

- Intelligence indicated that a field

front (divisional headquarters) was controlling the enemy regiments. If so,

this operation marked the first time any U.S. unit in Vietnam had opposed

a division-size unit of the North Vietnamese Army under a single commander.

-

- The first significant contact was

made on 1 November, when a platoon of Troop B, 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry,

overran a regimental aid station six miles southwest of Plei Me, killing fifteen

enemy soldiers and capturing fifteen more. This rifle platoon had been airassaulted

into the area in response to reports that scattered groups of enemy soldiers

had been sighted. Two more rifle platoons from A and B Troops were landed

to sweep through the area. Just after 1400 hours, scout helicopters discovered

a battalion-size enemy force moving from the northeast toward the U.S. platoons.

The fighting intensified at ranges too close for aerial rocket artillery or

tactical air support. The position was also beyond the range of available

tube artillery. Reinforcement platoons from the 1st and 2d Battalions of the

12th Cavalry and the 2d Battalion of the 8th Cavalry landed late in the afternoon,

followed by two additional platoons from the 2d Battalion, 12th Cavalry. Ground

fire was intense on all reinforcement, resupply, and evacuation helicopters,

and seven ships were hit by enemy fire. By 1700 hours Company B, 1st Battalion,

8th Cavalry, was committed to the battle, and by 1900 hours the platoons of

the 9th Cavalry Squadron, having found and fixed the enemy, were airlifted

from the area.

- [12]

- By the time the enemy was driven from

the field the 33d North Vietnamese Army Regiment had lost its aid station,

many patients, and over $40,000 worth of important medical supplies and had

sustained 99 men killed and 183 wounded.

-

- The airmobile concept had proved itself.

Scout ships would reconnoiter and locate enemy groups, rifle elements would

fix the enemy in place, and heliborne units, supported by massed air and ground

firepower, would attack and defeat the enemy troops. These tactics worked

successfully again and again during the battle.

-

- In a well-executed ambush at 2100

hours on 3 November, the rifle platoons of the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry,

again drew blood. Troops in one of several ambush positions located just north

of the Chu Pong Mountain sighted a heavily laden North Vietnamese Army unit,

estimated at company strength, moving along an east-west trail. Deciding to

take a break just one hundred meters short of the ambush site, the enemy column

loitered outside the killing zone for ninety minutes, while the U.S. troops

waited quietly in ambush. At 2100 hours the enemy unit moved noisily along

the trail. The first element was allowed to pass, and then the trap was sprung

with eight claymores along a 100-meter zone. The attack was perfectly executed

and the enemy's weapons platoon with machine guns, mortars, and recoilless

rifles was caught in a wall of lead as the cavalrymen fired continuously for

two minutes. There was no return fire.

-

- The ambush patrol returned immediately

to its base and went to work strengthening its perimeter. By 2230 hours the

base was under heavy attack by an estimated two or three companies of North

Vietnamese Army regulars. At midnight the perimeter was in grave danger of

being overrun, but reinforcements were on the way. Company A, 1st Battalion,

8th Cavalry, standing by at the Duc Co Special Forces Camp, located twelve

miles of roadless jungle to the north, had been alerted. The first platoon

was on the ground and in combat forty minutes after midnight. The entire company

had arrived by 0240 hours. While this type of relief and reinforcement is

now routine, it was unique in November 1965. This battle marked the first

time a perimeter under heavy fire was reinforced at night by heliborne troops

air-assaulted into an unfamiliar landing zone. It was also the first time

that aerial rocket artillery was used at night and as close as fifty meters

to U.S. troops.

-

- By dawn the enemy attack had lost

momentum, and the fighting diminished to occasional sniping from surrounding

trees. As a result of the battle, ninety-eight North Vietnamese soldiers were

killed and ten were captured. In addition, over 100,000 rounds of 7.62-mm.

ammunition, two 82-mm. mortars, and three 75-mm. recoilless rifles were destroyed,

and large quantities of mortar and recoilless rifle ammunition were captured.

The implications of an ambush deep within

- [13]

-

-

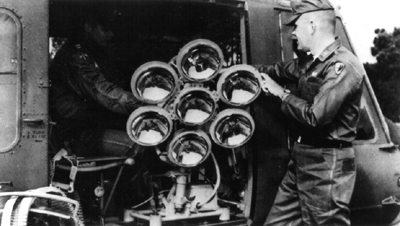

HUEY COBRA FIRING ROCKETS AT ENEMY

TARGET

-

- what was thought to be secure territory must have stunned the North Vietnamese

Army's high command.

-

- Although the helicopter was no longer

strange to the enemy, he had failed to appreciate its use in tactical roles

other than as a prime mover of supplies and men. For the first time the enemy

found his withdrawal routes blocked, his columns attacked, and artillery fire

directed on his routes of escape-all because of the new dimension added to

the war by aggressive tactical use of the helicopter. During the pursuit of

the 33d North Vietnamese Army Regiment from Plei Me, the enemy was so baffled

by the constant harassment and rapid compromises of "secure" way

stations that the North Vietnamese Army command concluded that there were

traitors in the regiment providing target information to the Americans.

-

- Arming Army aircraft had been tried

as far back as the 1950s, but the war in Vietnam brought about an intensive

program to develop Army aircraft weapons. In 1962 at Nha Trang, the 23d Special

Warfare Aviation Detachment (Surveillance), whose mission was to support provincial

forces, tested six OV-lA Mohawks armed with .50caliber machine guns and 2.75-inch

folding-fin aerial rockets. This successful program was expanded until 1966,

when Army fixed-wing aircraft were taken out of the fighter-escort mission

by the Department of Defense. No approved armament program was established.

-

- During this same period, the use of

armed helicopters increased rapidly. In October 1962, the Utility Tactical

Transportation Com-

- [14]

-

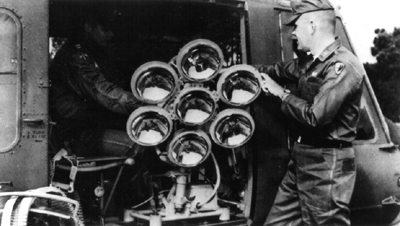

CH-47 CHINOOK-

- pany (the Army's first armed helicopter

unit) equipped with UH-lA's replaced B-26's and T-28's as escorts for CH-21

(Shawnee) troop helicopters. Losses decreased significantly. By May 1964,

B-model Hueys (UH-1B) had replaced the CH-21 for carrying troops, and ten

light airmobile aviation companies, with one to three armed platoons each,

were in Vietnam. In 1965 the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) brought the

first air cavalry squadron and aerial artillery battalion to the Republic

of Vietnam. Three armed Chinooks (CH-47A) were tested in 1966, but the arrival

of the Cobra (AH-1G) ended that project. The Huey Cobra was introduced in

1968 with 75 percent more ordnance and 30 percent more speed than any of the

Huey gunships. By April 1969, over half of the 680 helicopters in Vietnam

were Cobras.

-

- There were five types of U.S. Army

units operating in South Vietnam which were authorized to use armed helicopters:

assault helicopter companies (nondivision), attack helicopter companies (airmobile

division and nondivision), general support companies (infantry division),

aerial rocket artillery battalions (airmobile division), and air

- [15]

- cavalry troops (nondivision, divisional,

armored cavalry regiment). Armed helicopter missions were primarily oriented

to support ground maneuver forces. On such a mission, the helicopter's functions

were to provide security and to deliver firepower. There were five categories

of missions in which armed helicopters were commonly used: armed escort of

other aircraft, surface vehicles and vessels, and personnel on the ground;

security for an observation helicopter performing low-level reconnaissance;

direct fire support against targets assigned by a commander of a ground maneuver

element; aerial rocket artillery functions against targets assigned by a fire

support coordination center, forward observer, or airborne commander; and

hunter-killer tactics to provide security for an observation helicopter performing

low-level reconnaissance and to deliver firepower on targets of opportunity.

-

- One of the most significant

tactical innovations to come out of early U.S. efforts in Vietnam was the

"eagle flight." The exact origin of the term is obscure, but it

dates from the period in late 1962 when the five U.S. CH-21 helicopter companies

transporting ARVN forces were joined by the first company of armed UH-1 helicopters-the

Utility Tactical Transport Helicopter Company. An elite ARVN platoon was mounted

in five CH-21's and escorted by two to five armed Hueys. The gunships provided

suppressive fire in the landing zone and conducted aerial reconnaissance to

locate the enemy. The infantry could be landed to engage a small enemy force,

check a hamlet, or pick up suspects for questioning, while the gunships provided

support. If nothing was found, the troops would be picked up and the operation

repeated again in another likely location.

The eagle flight contributed greatly to ARVN operations. As one report stated,

"The enemy can fade away before the large formations, but he never knows

where the `Eagle Flight' will land next." The success of these early

operations demonstrated the feasibility of airmobile tactics in actual combat,

promoted the idea of armed helicopters, and paved the way I for the development

of much larger air assault forces. Such practical experience was infused in

the testing of the airmobile concept by the 11th Air Assault Division.

-

- The variety of aircraft organic to air cavalry permitted maximum flexibility

in organizing for combat and enabled the commander to structure the assets

into teams to satisfy mission requirements. One air cavalry

troop was organic to the armored cavalry squadron of the infantry division,

and three were organic to the air cavalry squadron of the airmobile

division. Each troop consisted of a scout platoon equipped with light observation

helicopters, an aerial weapons platoon with AH-1G armed helicopters, and a

rifle platoon with organic UH-1H utility helicopters. In Vietnam the commander

employed various teams in combat operations. A red team consisted of two gun-

- [16]

- ships, AH-1G Cobras, with

a variety of armament. It was strictly an offensive weapon, readily available

to the commander. A white team, consisting of two light observation helicopters

armed with 7.62-mm. miniguns, was used to reconnoiter areas where the enemy's

situation was unknown and significant contact was not expected. One of these

helicopters flew a few feet above the ground or trees to conduct close in

reconnaissance. The other flew at a higher altitude to provide cover and radio

relay and to navigate. The higher ship also functioned in a command and control

capacity. A pink team was a mixture of red and white, one light observation

helicopter and one Cobra. The observation helicopter followed trails, made

low passes over the enemy positions, and contoured the terrain in conducting

its reconnaissance mission. The gunship flew a circular pattern at a higher

altitude in the general vicinity to provide suppressive fire and relay information

gathered by the observation helicopter. When outside of artillery range or

in areas considered to be extremely dangerous, the pink teams were used in

conjunction with a command and control helicopter. If one helicopter was downed

by enemy fire, the remaining aircraft provided cover until a reaction force

arrived. Pink teams could also adjust artillery fire, although the AH-1G with

its twin pods of 2.75-inch rockets was comparable to a 105-mm. howitzer. Pink

teams were the most prevalent tactical combination of aircraft in the air

cavalry troop.

-

- A blue team was a structured number

of UH-1H aircraft transporting the air cavalry troop's aerial rifle (aerorifle)

platoon or part of a ground cavalry troop of the cavalry squadron. The blue

team normally worked with pink teams. The aerorifle platoon of the air cavalry

troop was transported in its organic aircraft in a great variety of roles.

When the aerorifle platoon was employed, a rifle company from one of the battalions

in the area was designated as the backup, quick reaction force. The air cavalry

troops were normally assigned ground and aerial intelligence, security, and

economy-of-force missions.

-

- Intelligence missions, oriented on

the enemy, included visual reconnaissance of routes, areas, and specific targets,

bomb damage assessment, landing zone reconnaissance and selection, target

acquisition, prisoner capture (body snatch), and ranger and airborne personnel

detector operations. The value of the air cavalry as the eyes of the commander

was inestimable. The body snatch was a special operation to capture prisoners

or to apprehend suspected enemy personnel. In such an operation, the helicopter

demonstrated its flexibility. Using an aircraft and ground force "package"

structured to the particular situation, the air cavalry commander pinpointed

the target individual by employing scout helicopters and then landed one or

more squads of the aerorifle platoons to accomplish the snatch. Scout air-

- [17]

- craft screened the area while the

Cobras provided cover. The snatch team package normally included a UH-1H command

and control ship to direct and co-ordinate the mission. Executed as a quick

reaction technique, body snatch operations provided the commander with a rapid

means of gaining new intelligence.

-

- Ranger long-range reconnaissance patrols

operated in small teams within the division area. The team members were qualified

for airborne operations and trained to rappel and use special recovery rigs.

They were capable of sustained operations in any type terrain for a period

of five to seven days. Air cavalry supported the rangers with UH-1H transport,

aeroweapons support, a command and control aircraft, and an immediate reaction

force of an aerorifle or airmobile platoon. Techniques to deploy the teams

included false insertions, low-level flights, and, on occasion, landing both

the aerorifle platoon and the ranger team simultaneously. The aerorifle platoon

was subsequently withdrawn, leaving the rangers as a stay-behind patrol. During

operations outside the range of tube artillery, the rangers relied heavily

on aeroweapons gunships (AH-1G).

-

- Security missions were primarily oriented

toward friendly forces to provide them with early warnings and time for maneuver.

Security missions included screening operations, first- and last-light reconnaissance

of specified areas, and protection for convoys and downed aircraft.

-

- Air cavalry troops often provided

surveillance of an extended area around a stationary or moving force. Pink

teams maintained radio contact with the ground commander and reported enemy

positions, trails, or troop sightings in order that appropriate action could

be taken. Pink or red teams were capable of engaging the enemy with their

own organic weapons and of adjusting artillery and air strikes to reduce an

enemy threat.

- When conducting first-light reconnaissance

around a unit field location, the pink teams began their flights before daybreak

to be on station at first light. En route the team leader contacted the ground

unit commander to request artillery advice and to ask whether the ground unit

had any particular area of interest. Last-light reconnaissance began an hour

and a half before dark in order to be completed by nightfall. When a target

was discovered, the team reported to the ground unit responsible for the area

and requested clearance to fire. All enemy sightings were reported to the

unit in whose area the teams were operating.

-

- The composition of a convoy security

force varied with the size of the convoy, the terrain, and the enemy's situation.

The scout elements, either one or two armed light observation helicopters,

provided fire support, radio relay, rapid artillery adjustment, and command

and control. The aeroweapons platoon could provide

- [18]

- quick fire support if the convoy were

ambushed, and the aerorifle platoon could be quickly brought in to assist.

Other helicopters were then used to move the backup reaction force quickly

into the ambush area.

-

- When an aircraft was downed within

the division area of operations, a pink team was immediately dispatched to

locate it. Then an aerorifle or ground cavalry platoon was brought into the

area. The pink team screened the area surrounding the aircraft until both

the aircraft and security platoon were evacuated, Although platoon personnel

were trained to rig aircraft for evacuation, the normal procedure was to bring

in a technical inspector and qualified maintenance personnel to prepare the

aircraft.

-

- Economy-of-force missions for airmobile

cavalry included artillery raids, combat assaults, ambushes, delaying actions,

prolonged security for elements constructing fire bases, and base defense

reaction force operations.

-

- Artillery raids supported by air cavalry

units included both the tube and aerial rocket artillery raids, delivered

into areas where the enemy considered himself safe from such fire. During

a tube artillery raid, the air cavalry troop reconnoitered the selected landing

zone and secured it with an aerorifle platoon before artillery was landed

by CH-47 and CH-54 aircraft. Pink teams conducted visual reconnaissance to

develop targets of opportunity and were capable of adjusting fire and conducting

immediate damage assessment.

-

- The aerorifle platoon was used to

exploit significant sightings or to conduct ground damage assessment. In raids

by the aerial rocket artillery battalion, the air cavalry units performed

similar missions except that no landing zone had to be selected and developed.

-

- Fire base construction missions involved

an aerorifle platoon, an engineer team, and a pink team. The aerorifle platoon

was inserted (by rappel, if necessary) into the proposed landing zone to provide

security for the engineers. After a landing zone had been cleared for one

ship, additional engineer equipment was landed to enlarge the area to the

required fire base dimensions. Pink teams conducted screening operations around

the troop elements; co-ordination was achieved through a command and control

aircraft. After a one-ship landing zone was prepared, infantry troops were

usually brought in, and the aerorifle platoon could then conduct reconnaissance

of likely enemy positions in the vicinity. This platoon was also capable of

conducting limited combat assaults and ambushes. When teamed with scout and

aeroweapons platoon elements of the air cavalry troop, it constituted a balanced

combined arms team.

-

- Although night helicopter assaults

were rare in the early operations in Vietnam, the Army did work toward developing

effective night techniques. Experience has shown that all missions and roles

- [19]

- normally fulfilled by helicopters

during daylight hours can be successfully completed in darkness by aircraft

equipped with navigation aids and night vision devices. Vietnam proved that

helicopters could be used at night to greatly increase U.S. maneuver superiority

over the enemy. Most of the night combat assaults were made to reinforce units

in contact with the enemy; however, they were also made to gain tactical surprise,

position blocking forces, and set up ambushes.

-

- The first night reinforcement of U.S.

troops under fire occurred during the firefight following the 1st Squadron,

9th Cavalry, ambush. The landing zone, which could accommodate only five helicopters,

was under continuous fire during all landings. The only light available to

the pilots was that from machine gun tracer rounds. This firefight also marked

the first time aerial rocket artillery was employed at night in close support

of friendly positions.

-

- The first night combat assault involving airmobile

105-mm. howitzers occurred on 31 March 1966 as part of Operation LINCOLN by

the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). When elements of the 1st Squadron, 9th

Cavalry, reinforced by a rifle company, became heavily engaged in

the early evening hours, a second rifle company and Battery B, 2d Battalion,

19th Artillery, were brought into a previously unreconnoitered landing zone

at 0105 hours. The fire support from the battery contributed significantly

to the total of 197 enemy soldiers killed in the engagement.

-

- The first U.S. battalion-size night

combat assault took place on 31 October 1966 when the combat elements of the

2d Battalion, 327th Infantry (Airborne), 101st Airborne Division, were lifted

into two landing zones near Tuy Hoa by the 48th and 129th Assault Helicopter

Companies and the 179th Assault Support Helicopter Company of the 10th Combat

Aviation Battalion. Twenty-four UH-1D, six UH1B, and four CH-47 helicopters

were used. The night before, the 10th Combat Aviation Battalion had conducted

a deception operation involving a simulated night combat assault with preparatory

fire by tactical air, artillery, and gunships and with illumination by flares.

The actual operation was executed without preparatory fire and illumination.

Pathfinders and security elements were positioned in the landing zones prior

to the main assaults. Helicopters flew nap-ofthe-earth flight paths to gain

further surprise.

-

- The desire to deny the enemy freedom

of movement at night led helicopter units to experiment with a variety of

lighting systems. The earliest systems were known as the Helicopter Illumination

System (Lightning Bug-Firefly) and were characterized by a fixed bank of C-123

landing lights mounted in a gunship. The crew would find and hold the target

with the lights while other gunships engaged the enemy. In the Mekong Delta

an OV-1C Mohawk was often used as part of the team, locating targets by an

infrared device and vectoring the

- [20]

FIREFLY ILLUMINATION SYSTEM

light ship onto the target. A series of refinements were made which included

developing a focusing arrangement for the illumination system, testing various

searchlights, and using the night observation device as a passive means of

detection.-

- When the Cobra was introduced into

the theater, the UH-1D/H Nighthawk was developed in the field. The basic components

of the Nighthawk were an AN/VSS-3 Xenon searchlight (component of the Sheridan

Armored Reconnaissance Airborne Assault Vehicle), a coaxially mounted AN/TVS-4

night observation device, and an XM-27 El 7.62-mm. minigun system. The searchlight

provided both white light and infrared, while the minigun system mounted in

the cargo +compartment allowed the Nighthawk to engage the target or provide

suppressive fire. Normal use involved a Nighthawk team (one UH-1D/H with the

light and one or two AH-1G gunships) working either an area or specific targets

already pinpointed through other methods.

-

- Ground controlled approach radar was

often used to provide navigational assistance to the team. The UH-1D/H would

fly at fifty knots 500 feet above the terrain with the gunships to the rear

at about 1,500 feet. When the light ship detected a target with infrared light,

it could either turn on the white light or open fire with the minigun, with

the accompanying gunships then firing into the minigun's tracer pattern. The

Nighthawk was very effective in flat, open terrain. In mountainous, canopied

jungle it was limited to roads, trails, and Rome plow cuts. Nighthawk was

employed to a limited extent in base camp defense, in checking out radar sightings,

in sensor activity, and in mechanical ambushes.

- [21]

- In May 1966, five UH-1C gunships equipped

with low-light-level television were deployed to Vietnam to test the use of

TV as a night vision and target detection aid. Operating in the Mekong Delta,

the gunships had limited success; however, the concept and the equipment needed

further refinement. In November 1969, three INFANT (Iroquois Night Fighter

and Night Tracker) systems arrived in Vietnam. Each system consisted of a

UH-1H helicopter with an M21 armament subsystem (7.62-mrn. miniguns and 2.75-inch

rockets) 'and an image intensification system for night vision, AN/ASQ-132.

This refined equipment was tested in night combat operations in the III and

IV Corps Tactical Zones. INFANT increased the ability of the helicopter to

perform its attack and surveillance operations at night.

-

- Helicopters also provided considerable

nighttime support to ground forces by using MK24 aircraft flares, by resupplying

ammunition in an emergency, and by evacuating the wounded. Base camp defenses

were strengthened by gunships, which flew mortar patrols, visually sighted

and attacked enemy mortars, and transported ready reaction forces to check

out radar sightings or to provide rocket and mortar support in standoff attacks.

However, the effectiveness of surveillance by aircraft at night, was limited,

because the noise of the aircraft warned the North Vietnamese Army and Viet

Cong of its approach and gave them time to hide.

- The U.S. Army developed a new surveillance

aircraft for use in Vietnam. In April 1967, Lockheed Missiles and Space Company

was selected to build two experimental, low-noise aircraft. In September 1967,

the so-called quiet airplanes were deployed to the IV Corps Tactical Zone

for sixty-day evaluation. Nothing more than a modified glider with a wooden

propeller driven by a 100-horsepower engine, the aircraft could fly slowly

and quietly while the pilot conducted visual reconnaissance. During the test,

the quiet airplanes !conducted reconnaissance missions before and after a

strike; surveillance operations over areas, canals, rivers, roads, and along

the coastline; and searches around the perimeter. When the test was concluded,

the aircraft was judged to be valuable; however, several improvements were

recommended. The Lockheed Aircraft Corporation then developed a much improved

model, which was designated the YO-3A, Quiet Aircraft. The YO-3A was a more

sturdy aircraft, powered by a muffled 210-horsepower engine. It had a night

vision aerial periscope with an infrared illuminator and a laser target designator.

The Quiet Aircraft was deployed to Vietnam in the summer of 1970.

-

- The largest fixed-wing aircraft in

the Army's inventory was the CV-2 Caribou. It was the workhorse of aerial

resupply in the early phases of the war. The CV-7 Buffalo, a turbinized version

of the Caribou, had a 30-percent increase in load-carrying capacity. Two Buffaloes

were flown from Fort Rucker, Alabama, to Vietnam in the

- [22]

YO-3A QUIET AIRCRAFT-

- fall of 1965 and evaluated during

combat missions. The results were quite successful; however, all the Buffaloes

as well as the Caribous were transferred to the U.S. Air Force in the spring

of 1967.

-

- The helicopter and airmobile techniques

gave the commander new capabilities; the old time-distance factors and terrain

considerations were outmoded. In the airmobile division, the helicopter was

not used just as a means of transporting by air-such as troop movement, reinforcement,

medical evacuation, and resupply-but was totally integrated into operations

by commanders at all levels. The readily available air assets were automatically

considered in maneuver plans against the enemy, in intelligence gathering,

in fire support, and in logistic operations.

- [23]

- page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents