- Chapter III:

-

- IRVING

(2-24 October 1966)

-

-

Operation IRVING

illustrates a number of innovations which were used throughout

Vietnam. These innovations represented important changes in the

tactical, technical, and psychological sides of warfare. The

helicopter played an enormous part, not only in lifting troops into

combat but also as aerial rocket artillery, in the evacuation of

casualties, in logistical support, and in the development of new

lightweight equipment. IRVING also demonstrates the use of civic

action and psychological warfare in counterinsurgency operations. In

addition to being outflanked by vertical envelopment, the enemy was

attacked by strategic bombers and by U.S. infantrymen invading his

underground hiding places.

-

- During October of 1966,

allied military forces combined efforts in three closely co-ordinated

operations to destroy the enemy in the central and eastern portions of

the Republic of Vietnam's Binh Dinh Province and to uproot the Viet

Cong's political structure along the province's populated coastal

region. In a period of twenty-two days, the 22d ARVN Division, the

Republic of Korea Capital Division, and the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division

(Airmobile) were to dominate the battlefield to such an extent that

the aggressor had only one alternative to fighting: surrender. The

enemy not only suffered heavy personnel losses in decisive combat, but

many of his vital logistic and support bases were discovered and

destroyed. The victory meant that the central coastal portion of Binh

Dinh Province and hundreds of thousands of citizens were returned to

the control of the South Vietnamese government. The people of the

province were freed from Viet Cong terrorism and extortion for the

first time in many years, and the groundwork was laid for a better

life. The U.S. 1st Cavalry Division's contribution in this campaign to

pacify Binh Dinh Province was Operation IRVING.

-

- IRVING began on 2

October 1966; however, the development of the battlefield started many

days before. The enemy had been driven out of his bases in the Kim Son

and 506 valleys and channeled toward the sea. In Operation THAYER I in

September, strong U.S., South Vietnamese, and Korean attacks from all

sides uprooted elements of the 610th North Vietnamese Army Division

from their mountain

- [24]

- sanctuaries, uncovering major

medical, arms, supply, and food caches, a regimental hospital, and a

large antipersonnel mine and grenade factory. A series of fierce

battles forced the enemy into a natural pocket bounded by the Phu Cat

Mountains on the south, the coastline on the east, the Nui Mieu

Mountains on the north, and National Route 1 on the west, The battle

lines for Operation IRVING had been drawn.

-

- The 1st Cavalry Division

planned for Operation IRVING in minute detail. The division staff

concentrated on intelligence, psychological operations, population

control, and civic action projects as well as combat operations. If

combat against the enemy was to be successful, the psychological,

population control, and civic action aspects had to be effective. In

the same pocket with the enemy were some 250,000 civilian residents,

plus important rice farming and salt production areas. To avoid

noncombatant casualties, population control measures were incorporated

into the psychological operations program. Some twelve million

leaflets and 150 radio broadcast hours were used during Operation

IRVING to help control the civilians. Curfews were established, and at

times villagers were requested to stay where they were until more

specific instructions were given. Psychological efforts were also

geared to appeal to the enemy. For example, substantial rewards were

offered for surrendered weapons.

-

- By D-day for Operation IRVING,

the Free World Military Assistance forces were in position. Elements

of the 1st and 3d Brigades of the 1st Cavalry Division air-assaulted

into objectives well inside the IRVING pocket. Simultaneously, the

ARVN and Korean elements coordinated attacks in the southern portion

of the battle area so that all three schemes of maneuver would

complement one another. The 22d ARVN Division launched a ground attack

to the northeast with two infantry battalions and two airborne

battalions. The Republic of Korea Capital Division attacked northward

through the Phu Cat Mountains. On the South China Sea, the ARVN junk

fleet and the U.S. Navy sealed escape routes to the sea and provided

fire support from the destroyers Hull and Folson and smaller

ships.

-

- The 1st Cavalry Division

attacked at 0700 hours on the morning of 2 October. Colonel Archie R.

Hyle, commander of the 1st Brigade, deployed the 1st Battalion, 8th

Cavalry, to gain objective 5060; the 2d Battalion, 8th Cavalry, to

secure objective 506A; and the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, to attack

objective 506B. The 3d Brigade commander, Colonel Charles D. Daniel,

attacked objective 507 using the 1st and 5th Battalions of the 7th

Cavalry. The 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, under the control of Major

General John Norton, the division commander, was assigned its normal

reconnaissance mission over the division's area of interest. Decisive

combat with the enemy was to occur shortly after the operation began.

- [25]

- Early on the morning of D-day,

elements of the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, were conducting

reconnaissance operations in the vicinity of Hoa Hoi and observed

seven North Vietnamese Army soldiers in the village. Troop A landed

its infantry elements in the village area and supported them with

armed helicopters. They soon were engaged against a large enemy force

that had fortified the village. When advised of the situation at Hoa

Hoi, Colonel Hyle called for the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, already

airborne en route to another objective. Lieutenant Colonel James T.

Root, commander of the 1st Battalion, issued new orders from his

command and control helicopter, and the battalion turned to the

rescue.

-

- B Company was the first unit

of the 1st Battalion to arrive at Hoa Hoi. Under the direction of

Captain Frederick F. Mayer, Company B landed 300 meters east of the

village and quickly maneuvered to assault the enemy's fortified

positions. Although wounded, Captain Mayer directed the unit's drive

toward the well-prepared enemy bunker system. While advancing across

an open area, the unit came under extremely heavy fire and was

momentarily pinned down. Members of the 2d Platoon, Company B, stood

up and advanced through the enemy fire. One squad, spearheaded by

Private, First Class, Roy Salagar, breached the heavily booby-trapped

perimeter trench, and within minutes the enemy force started

withdrawing into the village.

-

- At this time A Company

air-assaulted into an area southwest of Hoa Hoi. As the 3d Platoon

came in contact with the enemy, they also encountered civilian

noncombatants in the battle area. First Lieutenant Donald E. Grigg was

deploying his platoon to return fire when several old men, women, and

children walked between him and the enemy. He raced 150 meters through

concentrated fire, picked up two of the small children, and carried

them back to his own lines. The other civilians followed him to

safety. Lieutenant Grigg's platoon then closed in on the enemy and

forced him to withdraw into the village.

-

- While other elements of the

1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, were being air-assaulted into the battle

area, the battalion held its fire on the village. A psychological

operations helicopter circled the village with loudspeakers, directing

the civilians to move out of the village and into four specific areas

outside the perimeter. North Vietnamese Army soldiers were asked to

lay down their weapons. During the moratorium, many civilians and

soldiers did as they were directed. After one hour, when it was

evident that no one else was coming out of the village, the 1st

Battalion, 12th Cavalry, began moving in.

-

- Fierce fighting lasted

throughout the day as elements of the U.S. battalion assaulted the

fortified village. That evening, General Norton reinforced the 1st

Battalion, 12th Cavalry, with Companies A and C of the 1st Battalion,

5th Cavalry. Under the control of Colonel Root, the companies made a

night air assault on the beaches east of

- [26]

- Hoa Hoi and moved into the

encirclement to help contain the enemy during the hours of darkness.

North Vietnamese soldiers tried in vain to shoot their way out.

Effective artillery support contributed to the containment effort.

Earlier in the day, A Battery, 2d Battalion, 19th Artillery, had been

positioned by assault support helicopters to back up the 1st

Battalion, 12th Cavalry. During the night 883 105-mm. rounds were

fired in the effort to contain the enemy. The battlefield was

illuminated by a U.S. Air Force AC-47 flareship, by artillery, and by

naval guns from the destroyer Ullman. Throughout the night,

helicopters provided fire support, brought in supplies, and evacuated

casualties.

-

- At dawn, Company C, 1st

Battalion, 12th Cavalry, attacked south through the enemy position,

while Companies A and B blocked the other side of the village. The

enemy defended with great skill; but the strength of the attack, plus

the well-co-ordinated combat support, brought the battle of Hoa Hoi to

a close. During this 24-hour battle, the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry,

and supporting units had killed or wounded 233 enemy soldiers, while

suffering 3 killed and 29 wounded. In addition, 35 North Vietnamese

soldiers were captured, and 15 suspected NVA regulars were detained.

-

- On D-day of the operation a

B-52 strike was made on a portion of the Nui Mieu Mountains near

objective 506A. The 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, conducted a follow-up

damage assessment and discovered documents and seven enemy dead, which

confirmed the presence of elements of the 2d Viet Cong Regiment. All

forces advanced on schedule to reduce the size of the IRVING pocket.

The sweep to the sea continued, using helicopter assaults and land

movement to destroy the enemy forces. On 4 October a co-ordinated

ground attack was made by the 3d Brigade using the 1st and 5th

Battalions, 7th Cavalry. The attack was preceded by extensive

artillery preparation. Thirty enemy soldiers were killed in the

operation. As the sweep operations neared Nuoc Ngot Bay, leaflets and

loudspeakers were used to warn civilians that all boats moving on the

bay would be sunk. Riot control agents were also used during the

operation. The battalions of the 3d Brigade used assault boats brought

in by helicopter to sweep the waterways.

-

- On 5 October the 1st

Battalion, 12th Cavalry, air-assaulted back to the west into the Soui

Ca Valley to exploit a B-52 strike and to surprise enemy units that

had escaped the IRVING pocket or had secretly moved into the valley

strongholds. In the IRVING battle area, the 1st Cavalry Division

continued to search for North Vietnamese units and to uproot the Viet

Cong. The 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, sighted many small groups of

enemy soldiers trying to avoid contact. The cavalrymen fired at them

from armed helicopters and often landed infantry elements to engage

the enemy. On 9 October, while supporting

- [27]

CH-54 "FLYING CRANE" DELIVERING BULLDOZER TO FORWARD

POSITION

a sweep along the Hung Loc

peninsula, the 2d Battalion, 20th Artillery (Aerial Rocket Artillery),

fired SS11 missiles at bunkers on the peninsula. The missiles

destroyed the bunkers, thus enabling fifty-five Viet Cong to be

captured without a fight.-

- In mid-October, enemy contacts

in the coastal region diminished, and the emphasis of the battle

shifted back to the valleys in the west. Capitalizing on the

information that elements of the 2d Viet Cong Regiment were regrouping

in the Kim Son and Soui Ca valleys, the division quickly airlifted

several battalions into the area. On 13 October, the 1st Battalion,

5th Cavalry, located the main Viet Cong province headquarters,

including official stamps, radios, documents, and typewriters. On 14

and 15 October, in support of the 1st Battalion, Company A of the 8th

Engineer Battalion brought in airmobile engineer construction

equipment. A CH-54 "flying crane" lifted a grader and a

pneumatic roller into the valley. Teams of engineer soldiers called

tunnel rats located, explored, and later destroyed extensive tunnel

complexes constructed by the enemy. Sweep operations in the valleys

turned up additional caches of equipment and supplies.

-

- During the latter part of

Operation IRVING an artillery raid was conducted by A Battery, 2d

Battalion, 19th Artillery. Four howitzers

- [28]

- with crews, 280 rounds of

ammunition, and a skeleton fire direction center were airlifted into

areas that the enemy had thought were secure to fire on previously

selected targets that were beyond the range of other tube artillery. The

280 rounds were fired in less than seventeen minutes, after which the

artillery was airlifted back to its base.

-

- By midnight of 24 October the

battle was over. The enemy had been unable to cope with the airmobility

and versatility of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Massive

firepower had decimated the enemy's forces, and his long-secure supply

bases had been destroyed. While suffering 19 men killed itself, the 1st

Cavalry Division had killed 681 enemy soldiers and captured 741. The

rapid reaction of U.S. forces allowed the division for the first time to

capture more enemy soldiers than it killed. The success of Operation

IRVING had a lasting effect on the pacification of Binh Dinh Province.

-

- The major tactical innovation

illustrated in Operation IRVING Was airmobile combat. An airmobile

operation is one in which combat forces and their equipment move about

the battlefield in aircraft to engage in ground combat. In such an

operation, helicopters not only transport the forces to the battle area,

but also enable them to develop the situation and to reinforce,

withdraw, and displace combat power during the battle. The purpose of an

airmobile assault is to position fresh combat troops on or near-their

tactical objectives. The tactical unit can fly over obstacles and

impassable terrain to land at the strategic point in the battle area.

-

- The successful airmobile

assaults in Operation IRVING and those conducted by other units in

Vietnam were the result of detailed planning by the participating ground

units, the aviation support elements, and the combat support and combat

service support units. The overall commander of ,an airmobile task force

is the commander of the ground unit making the assault. The aviation

commander directs the helicopter support units and advises the task

force commander on all aviation matters.

-

- Airmobile operations in Vietnam

were planned in an inverse sequence, similar to airborne operations.

First, the ground tactical plan was prepared. It was the basic airmobile

operation plan. In this plan the commander of the assault unit presented

his scheme of maneuver and plan for fire support in the objective area.

Assault objectives were chosen that insured the accomplishment of the

mission. Landing zones were then carefully selected to support the

ground tactical plan. A fire support plan was developed concurrently in

order to be closely co-ordinated and integrated with the scheme of

maneuver.

-

- The next step in the sequence

was the development of a landing plan. It insured the arrival of the

various elements of combat power at

[29]

- the times and locations

required. The landing plan included the sequence, time, and place for

landing troops, equipment, and supplies.

-

- An air movement plan was then

prepared, which was based on the previous plans. Its purpose was to

schedule the movement of troops, equipment, and supplies by air from

pickup to landing. Details such as flight speeds, altitudes, formations,

and routes were specified.

-

- Finally, a loading plan was

developed. It insured the timely arrival of units at pickup zones and

the loading of troops, equipment, and supplies on the correct aircraft

at the proper time.

-

- Often, because of rapidly

changing tactical situations, the airmobile planning sequence was

abbreviated. All elements of the planning were considered, but in a

shorter form. The actions of Colonel Root of the 1st Battalion, 12th

Cavalry, in Operation IRVING provide an excellent example. Plans were

prepared for an airmobile assault by the 1st Battalion on objective

506B. However, when directed at the last minute to assault the village

of Hoa Hoi, Colonel Root prepared and assigned new orders while en route

by air to the new objective. Sound training and complete standing

operating procedures for the ground and aviation units contributed to

the quick development of airmobile plans and orders.

-

- Radio communications and

prearranged visual signals, colored smoke, and flares were the primary

means of communication during airmobile assaults.

-

- Fire support was extremely

important during these operations and included artillery, naval gunfire,

armed helicopters, tactical aircraft, strategic bombers, and mortars.

During a specific operation the task force may have been supported by

any or all of these means. All available fire support was controlled by

the airmobile task force command group from its command and control

helicopter. Preparatory fire on and around the landing zone was usually

brief but intense and continuous, with no pause in the firing from the

various sources. Fire was shifted from the landing zone only seconds

before the first flight of helicopters touched down. The firing was

diverted to selected locations to protect the assault force, and then

redirected to support the expansion of the objective area. Smoke was

often used by artillery or by a specifically equipped helicopter to mask

the movement of the assault force.

-

- Division commanders in Vietnam

concluded that airmobile assaults greatly increased the speed and

flexibility of their operations, extended their area of influence, and

provided them with the means to concentrate forces quickly and to move

them after accomplishing the mission.

-

- In World War II and in the

Korean War, where combat ranges were normally greater than in Vietnam,

gunnery errors seldom resulted in friendly casualties. Any round that

cleared friendly lines was

- [30]

- usually safe. In Vietnam,

however, about 50 percent of all artillery missions were fired very

close to friendly positions or into an area virtually surrounded by

converging friendly forces. An error could harm U.S. or allied troops or

civilians living in the areas of operations. The senior officer in

charge of each area of operation was specifically charged with the

safety of his troops and of the local population. His fire support co-ordinator

worked out the details required to insure this safety. He used such

devices as no-fire lines, fire and fire support co-ordination lines, and

clearances with the lowest level of the Republic of Vietnam government

(usually the district) that had U.S. advisers. Fire support co-ordinators

maintained a map marked to show specified-strike zones and no-fire

zones, all based on the rules of engagement drawn up jointly by U.S. and

Vietnamese high commands. They were applicable to all allied forces and

were meant to protect the lives and property of friendly forces and

civilians and to avoid the violation of operational and international

boundaries. The rules were specific. They covered each general type of

operation, such as cordon and search, reconnaissance in force, a

waterway denial operation, and defense of a base camp. They also

governed the establishment of zones. No-fire zones were those in which

persons loyal to the Republic of Vietnam government lived. The rules

provided for the different curfew hours which each province chief

specified for all Vietnamese civilians in urban centers, along main

supply routes, in New Life hamlets, and in the woods and fields.

Presumably, all persons who were not in a no-fire zone obeying curfew

restrictions were suspect.

-

- Naturally, the rules did not

limit the right of a unit to defend itself, and a unit attacked could

take necessary aggressive action against the enemy with any means

available. As Major General Harris W. Hollis later stated:

- The clearest test of the

hostility of a target was the receipt of fire from it-prima facie

evidence, as it were. In such cases our units or aircraft could return

fire as a matter of self-preservation, but only to the degree necessary

to deal with the threat. No overkill airstrike could be called down on a

Viet Cong sniper without proper prior clearance. I am convinced that

this restraint by each responsible commander played a key role in

minimizing civilian casualties.

-

- The most serious problem created

by clearance requirements was the loss of indirect fire responsiveness

and surprise. As a rule, clearances added approximately three minutes'

delay for each agency required to take action on the request. Agencies

within a unit caused the least delay and complications.

-

- To reduce the time lost in

firing missions, nonpopulated areas were frequently cleared in advance

of operations and for night intelligence and interdiction fire.

Commanders were expected to establish appropriate liaison with local

government agencies and with Free

[31]

- World forces to provide quick

request channels and to mark specified-strike zones whenever possible.

-

- With the tremendous increase in

the use of aircraft in the Republic of Vietnam came the need to assign

responsibilities for their safety from indirect ground fire. Operational

responsibility for the air advisory agencies was usually given to the

major field artillery headquarters in the area. The agencies were

generally located with a battalion operations section. Aircraft entering

the area of an air advisory agency usually radioed in for clearance.

They were given the locations of all fire or of safe routes to travel.

The agency notified aircraft in its area about new artillery missions by

calls over its network. The responsibility for all fire above 5,000 feet

was passed by the air advisory agencies to the U.S. Air Force.

-

- An important innovation in

the Vietnam War was the integration of strategic air power into the

ground combat plan. Similar use of heavy bombers in Korea was on a much

more limited scale. The Strategic Air Command, with its B-52 bombers

flying at extremely high altitudes, out of sight and out of hearing of

the unsuspecting enemy, delivered devastating blows against fortified

positions. Two B-52 strikes were used in Operation IRVING.

-

- Ground commanders used the

B-52's against targets of high tactical value. Enemy troop

concentrations in base areas were common targets. When a B-52 target was

identified, a request was passed through command channels to a joint

Army-Air Force targeting committee. If the request was approved, the

target was included in the bombing schedule and the requesting unit was

notified. The tactical commander could then complete his plans for using

the B-52 strike to its best advantage on the ground. The follow-up

operation after the bombing raid, depending on the nature of the target,

ranged from a small patrol reconnoitering the area to a large-scale

sweep operation involving a battalion-size unit or larger. Artillery was

often used following a B-52 strike to hit enemy personnel moving back

into the target area.

-

- The tactical mobility furnished

by the helicopter and the communications available to the ground

commander were effectively used to capitalize on B-52 strikes. While the

dust and smoke from the bombs were still in the air, the heliborne

assault could begin, taking maximum advantage of the shock and confusion

among the enemy troops.

-

- One of the major artillery

innovations of the Vietnam War was aerial rocket artillery, commonly

called ARA, and later, aerial field artillery. The fire support

potential of the helicopter had been appreciated for some time.

Gunships, in the form of UH-1 helicopters armed with various

combinations of machine guns, rockets, and grenade launchers, had been

effectively used throughout the conflict.

- [32]

- Theoretically, however, the

gunships provided light fire support rather than the artillery type.

Aerial rocket artillery, on the other hand, was organized and employed

as artillery. In the words of Lieutenant Colonel Nelson A. Mahone, Jr.,

commander of the 1st Cavalry Division's 2d Battalion, 20th Artillery (ARA),

"We consider ourselves a breed apart, and our success tends to

support this." Aerial rocket artillery fire was requested through

artillery channels and was usually controlled by an artillery forward

observer. ARA was particularly effective in support of airmobile forces

beyond the range of the division's ground artillery. Moreover, ARA

fulfilled the need for a highly responsive and discriminating means of

fire support for the infantry during its most vulnerable phase of an air

assault, namely, just after its arrival on the landing zone. Aerial

rocket artillery helicopters circling overhead watched over the landing

zone and movement of the troops. If necessary, they immediately

responded to fire requests by firing directly on the target.

-

- Although ARA was frequently used

beyond the range of cannon artillery, it also augmented this fire. ARA

was assigned the normal tactical missions of conventional artillery.

Normally, however, it was used in general support with control retained

by division artillery because of ARA's range and flexibility.

-

- The main armament of the ARA

consisted of the M3 2.75-inch folding-fin rocket system mounted on UH-1

helicopters, and later on the Cobra version. In addition, the ARA was

capable of using the SS 11 antitank wire guided missiles. SS 11 fire was

extremely valuable against point targets, such as bunkers located on

hillsides and other enemy fortifications. Medium and heavy artillery in

Vietnam was normally located in semipermanent base camps or fire bases

to provide support within the tactical area of operations. Continuous

fire, or the threat of it, from these weapons caused the enemy to move

his base camps and supply caches out of range. The artillery raid was

used against these outlying enemy installations by moving to a position

in range of the target, firing on the enemy, and then returning to the

artillery's base. Medium and heavy self-propelled weapons were

particularly well suited for raids, although light and medium artillery

lifted by helicopters could be used. In fact, the airmobile divisions

achieved excellent results with helicopter-borne 105-mm. howitzers used

in this fashion, and they developed expedient methods of clearing jungle

artillery bases. This technique was used effectively in Operation

IRVING.

-

- In October 1969, the 101st

Airborne Division (Airmobile) developed the radar raid in order to

extend the influence of its artillery. This type of raid was conducted

by frequently moving AN/PPS-4 or AN/PPS-5 radars with security forces to

dominant terrain features outside fire bases. These forces could then

provide surveillance along

- [33]

- routes of infiltration

previously masked by terrain. By conducting raids within existing

artillery ranges, discovered targets could be rapidly engaged.

-

- During Operation IRVING, Company

C, 2d Battalion, 8th Cavalry, discovered a tunnel complex in the Nui

Mieu Mountains. The complex included five vertical shafts, thirty to

fifty feet deep, with horizontal tunnels connecting them. After

searching the tunnels, a squad of engineers from the 8th Engineer

Battalion destroyed the complex with demolitions.

-

- A significant feature of the war

in Vietnam was the widespread use of tunnels and other underground

facilities by the enemy. Tunnels were a major factor in the enemy's

ability to survive bombing attacks, to appear and disappear at will, and

to operate an efficient logistic system under primitive conditions. By

the end of 1970, 4,800 tunnels had been discovered. Most of the

discoveries were made during sweep operations by Free World military

forces. Tunnel complexes were also located through local informers and

by means of dogs trained to find underground facilities. An electronic

tunnel detector and a seismic detector were tested with limited success.

Several techniques have been developed to force the enemy to evacuate

tunnels. Tunnel rat teams were formed by many infantry and engineer

units to clear and explore tunnels. An exploration kit consisting of

headlamps, communications equipment, and a pistol assisted the team. A

Tunnel Explorer Locator System was developed to map the tunnel and to

monitor the progress of the tunnel rat as he moved through the tunnel.

Proven chemical techniques were the use of smoke to locate tunnel

openings and a riot control type of tear gas, known as CS, to drive

enemy personnel from underground.

-

- After tunnels were cleared and

searched, they were destroyed to prevent their further use by the enemy.

Methods developed to keep the tunnels from being used again included

placing riot control agents in the tunnel, sealing the entrance with

explosives, using demolitions to destroy the tunnels, pumping acetyline

into the tunnel and igniting the gas by explosives, and using

construction equipment to crush the tunnels.

-

- The first use of riot control

agents in Vietnam was on 23 December 1964 when CS grenades were

air-dropped as part of an attempt to rescue U.S. prisoners being held at

a location in An Xuyen Province. In this operation no contact was

actually made with the enemy. In February 1965, General Westmoreland

informed the senior advisers of the four corps tactical zones that U.S.

policy permitted the use of riot control munitions in self-defense. Kits

containing protective masks and CS grenades were issued to each

subsector advisory team for self-defense. These kits were not intended

for offensive use by U.S. troops.

- [34]

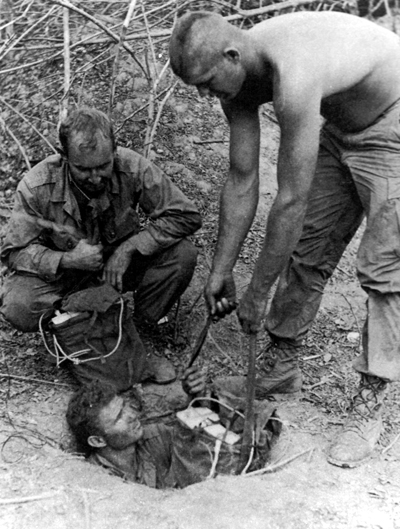

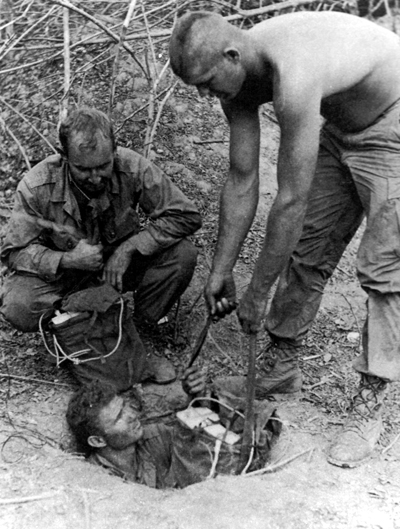

MEMBERS OP AN ENGINEER TUNNEL RAT TEAM explore

Viet Cong tunnel.- [35]

- In March 1965, New York Times

correspondent Peter Arnett described the use of riot control agents by

ARVN forces. His report generated much controversy in both the

American and foreign press and led to an examination, by both U.S.

military and political agencies, of the pros and cons of the use of CS

in Vietnam. An independent action by the commander of the 2d

Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, on 5 September 1965 significantly

influenced subsequent policy on the use of CS in Vietnam. The 2d

Battalion encountered an enemy force entrenched in a series of

tunnels, bunkers, and "spider" holes. Since there was

information that women and children were also present, CS was used to

help clear the complex. As a result, 400 persons were removed without

serious injury to noncombatants. However, on 7 September 1965, all

senior U.S. commanders were reminded that "MACV policy clearly

prohibits the operational use of riot control agents."

-

- Later the same month, the

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), decided that the military

usefulness of CS warranted a request to higher authority for

permission to use it in the upcoming Iron Triangle operation. The

request was forwarded to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, who

granted permission for CS to be used in the Iron Triangle operation

only. In the following weeks, a much-liberalized policy on the use of

CS was developed, and on 3 November 1965 the joint Chiefs of Staff

notified General Westmoreland that he was authorized to use CS and CN

(another tear gas) at his discretion to support military operations in

South Vietnam. This authority was further delegated to the major

commanders.

-

- MACV Directive 525-11, dated

24 July 1967, concerned the use of riot control agents in tactical

operations. Using these agents in situations where noncombatants were

involved was deemed particularly appropriate. The U.S. senior advisers

to the four ARVN corps were empowered to authorize the use of CS by

U.S. forces in support of the South Vietnamese Army. U.S. advisers at

all levels were to encourage their counterparts in the Vietnamese

armed forces to use CS and CN whenever such use offered an over-all

tactical advantage. The use of riot control agents in situations

involving civil demonstrations, riots, and similar disturbances was

specifically prohibited without prior approval by the commander of the

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Riot control agents were treated

as normal components of the combat power available to the commander.

-

- The early use of CS was

limited by the shortage of standard munitions. The only munitions

available at first in operational quantities were the M7 and M25

grenades. Many other ground and air munitions were being developed and

later were tested and used in Vietnam.

-

- One of the first uses for M7

CS grenades was to flush caves, tunnels, and other underground

fortifications. The 1st Cavalry Division

- [36]

-

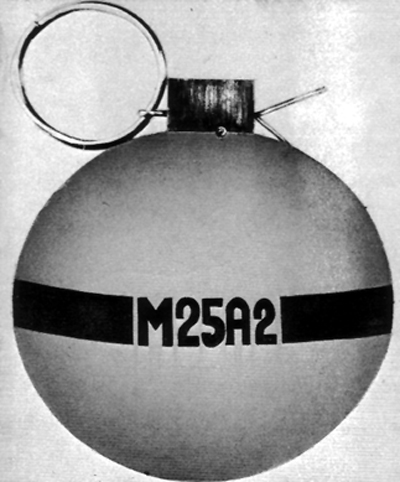

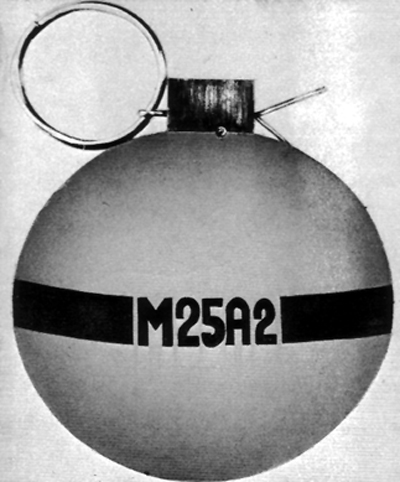

RIOT HAND GRENADE, CS1,

M25A2

-

- (Airmobile) effectively used

CS grenades during Operation MASHER-WHITE WING, which took place in a

highly populated area. CS grenades when used on suspected enemy areas

enabled 1st Cavalry troops to determine whether the occupants were

civilians in hiding or armed Viet Cong. On another occasion,

forty-three Viet Cong were pursued into a cave. All forty-three were

driven out again, however, when CS hand grenades were thrown into the

cave. The only casualty occurred when one Viet Cong refused to

surrender.

-

- The burning-type CS grenade,

along with HC smoke grenades, was also used in conjunction with the

M106 Riot Control Agent Dispenser, dubbed Mity Mite, a portable

blower. This system was capable of forcing the Viet Cong and North

Vietnamese Army out of unsophisticated tunnel complexes, as well as

helping to locate hidden entrances and air vents. The Mity Mite system

could not drive personnel from the more complex, multilevel tunnel

systems, many of which contained airlocks. However, bulk CS was widely

used in tunnel denial operations, in which bags of CS were exploded

throughout the tunnels. The 1st Infantry Division's experience

indicated that the tear gas remained effective for five to six months

if the tunnel was sealed. The efficiency of powdered CS in restricting

the enemy's use of fortifications and the difficulty of destroying the

numerous bunkers and other fortified structures by conventional

explosives led to the development of many techniques for dispensing CS

in these enemy defenses.

-

- The 1st Cavalry Division

(Airmobile) termed their expedient munition the Bunker Use Restriction

Bomb (BURB). The BURB consisted of a cardboard container for a

2.75-inch rocket warhead, two nonelectric blasting caps, approximately

twenty-five seconds of time fuze, and a fuze igniter. The device was

filled with CS and taped shut. The blasting caps provided sufficient

explosive force to rupture the container and to spread the CS49. Other

units developed their own expedient CS munitions for contaminating

fortifications.

- The acceptance of CS as a

valuable aid in combat operations led to the development of several

weapons systems. These included the E8 riot control launcher; the XM15

and XM165 air-delivered tactical

- [37]

- CS clusters; the 40-mm. CS

cartridge for the M79 grenade launcher; the 4.2-inch mortar CS round;

the BLU52 chemical bomb (Air Force); and the XM27 grenade dispenser.

The E8 chemical dispenser was used effectively by the 2d Battalion,

5th Marine Regiment, during Operation HUE CITY between 3 and 15

February 1968. The action during this period was characterized by

close, intense house-to-house combat. Engagements with the enemy were

usually at distances from 20 to 150 meters, with maximum distances of

300 meters. The use of air and artillery forces was limited by weather

conditions and by the closeness of the enemy to friendly troops. The

tactical situation required almost continual assaults on fortified

buildings and some bunkers. The use of the E8 CS dispenser was

credited with neutralizing the enemy's firepower during the assaults.

-

- The greatest amount of CS

employed in Vietnam was bulk CS1 or CS2 dispensed to restrict the

enemy's use of terrain. Contamination of large areas or of terrain not

accessible to friendly ground forces was normally carried out by

air-delivered 55-gallon drums that contained eighty pounds of CS. The

drums were dropped from CH-47 helicopters using locally fabricated

racks, which allowed the unloading of thirty drums on the target. The

major targets for these drops were known or suspected base camps, rest

areas, and infiltration routes.

-

- Air-delivered, burning-type

munitions also produced good results as evidenced by the use of thirty

E158 air-delivered CS clusters in support of South Vietnamese Rangers

on 3 February 1968. The Rangers were heavily engaged by a large Viet

Cong force deployed in a factory complex in the Cholon area of Saigon.

After several attacks by the Rangers had been repulsed, the CS

munitions were dropped into the area by helicopter. The Ranger assault

which followed the CS drop was successful.

-

- The use of riot control agents

by U.S. and allied forces in Vietnam cannot be likened to the gas

warfare of previous wars. Whereas mustard and chlorine gas often

resulted in permanent injury and death, CS and CN produced only

temporary irritating or disabling physiological effects. Their use

saved the lives of many allied soldiers, civilians, and enemy

soldiers.

-

- Because of the extensive use

of helicopters in the Republic of Vietnam, landing zones had to be

rapidly constructed in heavily forested areas, like those surrounding

the Kim Son and Soui Ca valleys. The engineers in Vietnam were thus

challenged to reduce the landing zone construction time, in order to

meet the needs of the quickly shifting tactical situation. Landing

zone requirements ranged from the hasty construction of a helicopter

pad, from which to provide emergency resupply or medical evacuation,

to the development of large landing zones, able to handle sufficient

aircraft to support battalion or brigade operations.

- [38]

- Experience gained by engineer

units in Vietnam led to the development of landing zone construction

kits that contained the necessary tools and demolitions to prepare a

landing zone for one aircraft. If the engineer team could be landed

near the new construction site, they would rappel from the helicopter

or climb down rope ladders. When sufficient area had been cleared,

air-portable construction equipment or additional tools and

demolitions were lifted in to expand the new landing zone.

-

- The "combat trap"

was developed after experimentation. In a joint Army and Air Force

effort, an M121 10,000-pound bomb was parachuted from a fixed-wing

aircraft or helicopter over the desired landing zone site and

detonated at a height that would clear away the dense foliage but not

create a crater in the earth. After the combat trap had finished its

job, a construction party and equipment were taken by helicopter to

the new landing zone to expand it to the desired size.

-

- The key to the success of

airmobile operations often was the ability of the engineer battalion

to construct landing sites for helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft

quickly. To support the airmobile division adequately, air-portable

construction equipment was developed for the division's engineer

battalion. Engineer equipment that could be moved into the forward

areas by helicopter included roadgraders, bulldozers, scoop loaders,

scrapers, and cranes, each of which was sectioned and lifted into the

objective area in two loads,, and then assembled for operation.

Backhoes, small bulldozers, dump trucks, and compaction equipment

could be transported in one helicopter lift.

-

- Throughout Operation IRVING

the 8th Engineer Battalion used airmobile construction equipment to

clear and expand landing zones and artillery positions and to

construct defensive positions. On 14 October, a bulldozer, a grader,

and a roller were sectioned and airlifted to the command post of the

1st Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, to expand the existing landing zone

and to construct an aircraft refueling area.

-

- The cry of "Medic!

Medic!" has been heard in all wars involving the United States,

and the company aidman is still the first link in the chain of medical

support. In Vietnam the aidman had a new lifesaving tool, the medical

evacuation helicopter, better known as Dust-off. Because of the

bravery and devotion to duty of these helicopter pilots and crews,

many lives were saved. Often Dust-off choppers landed under heavy

enemy fire to pick up wounded soldiers or hovered dangerously above

the battlefield as an injured man was hoisted up to the helicopter.

The seriously wounded were taken directly from the field to a

hospital, often bypassing the battalion aid station and the clearing

station. This rapid means of evacuation saved many lives and greatly

improved the soldiers' morale. Each soldier

[39]

DUST-OFF HELICOPTER HOISTS WOUNDED MAN FROM BATTLEFIELD- [40]

- knew that if he were wounded

he would be picked up immediately by Dust-off.

-

- Although the helicopter was a

great help to the men in Vietnam, it required considerably more

engineer support than the Army originally expected. As the commanding

general of the engineers in Vietnam, Major General David S. Parker,

noted in his debriefing report, "In addition to advanced landing

zones, built primarily by division engineers through a number of

ingenious techniques, there have been extensive requirements for

revetments, parking areas, maintenance hangars, and paved working

areas for POL, ammunition, and resupply operations. The construction

has increased effectiveness through added protection and improved

maintenance."

-

- Parked aircraft were prime

targets for the enemy and, as such, were subjected to many damaging

small arms, mortar, and .rocket attacks. Therefore, the protection of

organic aircraft was a major concern to all commanders. Engineers were

charged with providing lightweight, portable, and easily erected

revetments for all helicopters without decreasing the helicopter's

reaction time. Construction materials included airfield landing mats,

plywood, corrugated steel, and soil.

-

- The T17 nylon membrane was an

important development for engineer support of airmobile operations.

The membrane was designed as a moisture barrier and dust cover for

landing zones and strips. It was also used successfully as the surface

for unloading aprons and parking areas, thereby greatly reducing

construction time. It was not a cure-all, however, since it added no

bearing strength to the soil. The blast from helicopters often created

large dust clouds, which increased aircraft collisions and maintenance

difficulties. The T17 membrane was one way of reducing dust, but

peneprime, a commercial composition of low-penetration grade asphalt

and a solvent blend of kerosene and naphtha, was the best dust control

agent tried in Vietnam. During Operation IRVING, the 8th Engineer

Battalion used some 38, 600 gallons of peneprime on helicopter pads,

refueling areas, and airfield turnarounds.

-

- Operation IRVING was an excellent

example of recent changes in the tactics of war. The airmobile division, with

Vietnamese and Korean assistance, demonstrated its flexibility and power as

it pursued and destroyed a large enemy force in a populated countryside. The

helicopter became an integral part in maneuver plans, division artillery,

medical evacuation, and the transport of heavy equipment. The enemy was hit

with everything from strategic bombers to tunnel rats, within the confines

of special rules of engagement. Psychological operations and population control

were also included in the tactical plan.

- [41]

- page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents