- Chapter IV:

-

- Loc Ninh

- (October-November 1967)

-

- The 1st Infantry Division's

operations around Loc Ninh in October and November 1967 illustrates

many of the tactical and materiel innovations used by the infantry

commander in Vietnam. New formations and techniques were employed to

find the enemy. Dogs, starlight scopes, and anti-intrusion devices

helped the units to avoid being surprised. Carefully planned defensive

measures for small unit tactical perimeters were developed by the

division, and new, lighter weapons with increased firepower made the

foot soldier more effective. Other new techniques increased the

support provided by artillery, by air, and by Army aviation.

-

- Events leading up to the

battle of Loc Ninh included the engagement of the 1st Battalion, 18th

Infantry, with elements of the 271st Viet Cong Regiment at Da Yeu,

fifty-five kilometers south of the Loc Ninh airstrip. This firefight

clearly demonstrates fire support in Vietnam. It also illustrates the

use of scout dogs and the cloverleaf formation, a conventional

reconnaissance technique adapted to the infantry battalion's movement

toward contact with the enemy.

-

- The battle was fought in dense

scrub jungle, where observation was limited to ten feet. The lst

Battalion, 18th Infantry, was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Richard

E. Cavazos and had been operating in the vicinity of Da Yeu for seven

days, searching for elements of the 9th Viet Cong Division. On the

morning of 11 October Companies B and C and the battalion tactical

command post moved out of the position that the battalion had occupied

without contact during the night. Company B, commanded by Captain

Watson G. Caudill, led, followed by the tactical command group and

Company C, which was commanded by Major William M. Mann, Jr. The

mortars were left in the night defensive position with Company D.

(Company A was in Di An on a rear area security mission.) The mission

was to search for an enemy base camp believed to be two kilometers

north.

- The point squad of Company B

was accompanied by a scout dog, which immediately gave the alert as

the company cleared the perimeter. In response to the dog's alert, the

column proceeded in a clover-

- [42]

- leaf formation in order to

provide maximum security. No enemy was sighted; however, the point squad

reported hearing movement to its front and the dog continued to give the

alert. After covering 1, 800 meters, Captain Caudill directed his front

platoon leader, 1st Lieutenant George P. Johnson, to deploy his troops

in line and direct small arms fire into the forward area. The fire was

immediately returned from a range of thirty meters, whereupon Colonel

Cavazos ordered Captain Caudill to withdraw his platoons through each

other and move into the defensive perimeter being formed by Company C.

Meanwhile, Captain Robert Lichtenberger, Company B's forward observer,

had called in artillery. As the 1st and 2d Platoons withdrew through the

3d Platoon, he guided the artillery fire back with them until it was

falling only 100 meters from the 3d Platoon's positions and well inside

the initial point of contact. Second Lieutenant Ralph D. McCall had

selected an excellent position for his 3d Platoon to cover the

withdrawal of the remainder of, the company. His squads were linked with

Company C. Because the heavy enemy fire was ineffective, Colonel Cavazos

directed the 3d Platoon to maintain its position rather than pull back

into the perimeter.

-

- By 1015, forty-five minutes

after the initial contact, the first of nine tactical air sorties was

attacking 400 meters in front of Lieutenant McCall's 3d Platoon and just

north of the east-west fire coordination line that had been established

by Colonel Cavazos. Simultaneously, the artillery was striking in the

area between the 3d Platoon and the fire co-ordination line.

-

- At 1020, a helicopter light fire

team entered the battalion net for instructions. After noting the smoke

that identified the front and flank elements, the fire team leader began

to search the battalion's west (left) flank. He had been directed to run

from south to north, to work his fire up to the artillery impact area,

and to break west to avoid conflict with the fighters which were

striking from east to west and breaking north. The enemy reacted

immediately to the fire team's first run. Seventy-five Viet Cong, who

had been hiding on the left flank, assaulted the 3d Platoon. They were

cut down by the U.S. infantrymen firing from their positions behind

trees and anthills. The charge ended as abruptly as it started. The 3d

Platoon was moved back into the perimeter as the artillery was shifted

even closer to the battalion's position. After another hour, in which

artillery, tactical air forces, and helicopter fire teams continued to

work the area, enemy firing ceased and the battalion (minus) moved

forward. Twenty-one bodies were found in the enemy position. The 1st

Battalion, 18th Infantry, had one man killed and four wounded (all from

the 3d Platoon of Company B) during the Viet Cong assault.

-

- During the three-hour contact,

the battalion was never decisively engaged. The final assault into the

enemy position was not started

- [43]

-

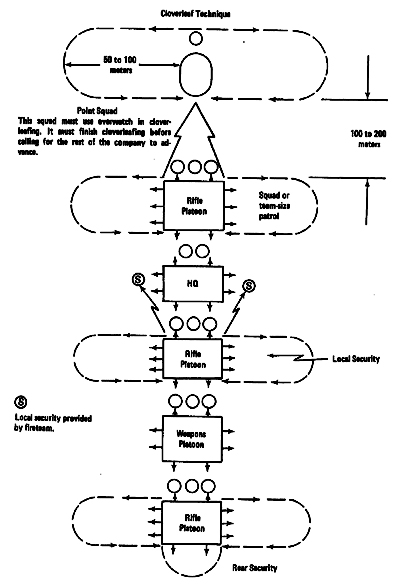

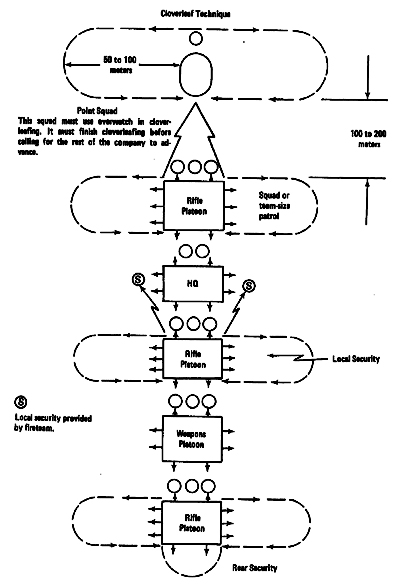

Diagram 1. Rifle company cloverleafs, advancing toward contact

-

[44]

- until enemy firing had ceased.

The combined firepower of tactical fighters, armed helicopters, and

artillery was directed simultaneously on the enemy position, which had

been detected from an airborne scent picked up by a scout dog.

-

- The cloverleaf formation, named

for the trace of the patrols that emanated from the main column, was

used habitually by the 1st Infantry Division when contact with the enemy

was imminent. It provided for a deliberate search of the flanks of a

column and for an "overwatch" technique used by the point

squad. (Diagram 1) In the overwatch, one element moved while another

element occupied a position from which it could fire immediately in

support of the advancing point men. Using this formation, the enemy

position was discovered before the entire unit became engaged.

-

- Assigning the helicopter fire

team to cover the battalion's flank was another new technique in the

Vietnam War. Although successful commanders in all wars have been

concerned about the security of their units' flanks, the war in Vietnam

demanded even greater attention. This new emphasis resulted from the

relative independence of small unit operations, from the nature of the

terrain, and from the enemy's ability to hide his formations close to

U.S. forces.

-

- Scout dogs also proved to be a

valuable innovation. A scout dog team consisted of one dog and one

handler, trained to work together and inseparable for operational

purposes. Scout dogs were German shepherds and normally worked on a

leash. They were trained to respond to airborne scents by signaling

their handlers when they picked up a foreign presence. Scout dogs could

locate trip wires, mines, fortifications, tunnels, and storage areas.

Under ideal conditions, they could detect groups of people several

hundred meters away; however, fatigue, adverse weather conditions, and

dense vegetation affected their performance. In addition to the scout

dog was the tracker dog. The tracker, a Labrador retriever, was part of

a team consisting of the dog, his handler, and four men trained in

visual tracking techniques. The dog, working on a 25-foot leash,

followed a ground scent over terrain where the soldier-trackers were

unable to pick up visible signs. The first combat tracker teams used in

Vietnam were trained by the British in Malaya. Now the Military Police

School at Fort Cordon, Georgia, has the facilities for tracker training.

-

- The battle of Da Yeu was an

unqualified defeat for the North Vietnamese Army; it was indicative of

the outcome of subsequent contacts in the vicinity of Loc Ninh. Loc Ninh

is a district town 13 kilometers from the Cambodian border and 100

kilometers north of Saigon. The town was slated as a target by the 9th

Viet Cong Division for late October. The timing coincided with the

inauguration of President Nguyen Van Thieu; the seizure of a district

capital by the enemy could have had substantial political impact.

-

[45]

SCOUT DOG LEADS PATROL

SEARCHING FOR VIET CONG-

- During the weeks that preceded

the battle, the headquarters of the 9th Viet Cong Division left War

Zone D for the border area north of Loc Ninh. The division

headquarters moved with the 273d Viet Cong Regiment and approached the

border areas where the 272d Regiment had already assembled. The 271st

Regiment, the third of the division's three regiments, moved into the

Long Nguyen secret zone, fifty kilometers south of Loc Ninh. A

captured enemy document indicated that this move was made to

facilitate the logistic support of the 271st Regiment. However, after

several contacts with elements of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division,

including the battle of Da Yeu, the 271st Regiment withdrew from the

area in late October. The regiment had sustained over 400 killed in

action during its brief tenure in the Long Nguyen secret zone, and it

was probably too weak to be committed at Loc Ninh. The 165th Viet Cong

Regiment was subsequently directed to provide additional men to the

9th Division in order to fill in the ranks.

-

- The enemy's scheme of maneuver

directed the 272d and 273d Viet Cong Regiments to converge on Loc

Ninh. The 272d Regiment was to approach from the northeast and the

273d was to approach from the west, The operation began at 0100 hours

on 29 October, when the

-

[46]

-

CIDG COMPOUND AND LOC NINH AIRSTRIP

with A Battery, 6th Battalion,

15th Artillery, position in the foreground.

-

- 273d Regiment attacked the

district headquarters and the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG)

and Special Forces camp at the Loc Ninh airfield. The 273d Regiment

pressed the attack until 0535 when it was forced to withdraw.

Although it had briefly penetrated the CIDG compound, it left 147

Viet Cong bodies on the battlefield. ,

-

- In reaction to the attack,

Major General John H. Hay, Jr., commander of the 1st Infantry

Division, alerted four battalions and their supporting artillery.

General Hay's plan was to deploy the battalions in a rough square

around Loc Ninh. A study of the terrain and the pattern of enemy

activity in the area revealed the most probable enemy routes of

approach and withdrawal. The battalions were to set up night

defensive positions at the corners of the square and to block the

enemy's withdrawal. Artillery was to be placed in each of the night

defensive positions to insure mutual support as well as support for

the maneuver battalions' operations. The locations of these

positions-temporary fire bases-on routes essential to the enemy

would challenge him to attack; and as he massed for the assault,

fire from supporting artillery, tactical fighters, and helicopter

fire teams would be directed on his exposed formations. In addition

to the units along the routes of withdrawal, the plan included

bolstering the defenses of Loc Ninh with a small force of infantry

and artillery.

-

- At 0630 on 29 October the

1st Battalion, 18th Infantry, commanded by Colonel Cavazos, made an

air assault into the southwestern corner of the square, four

kilometers west of the Loc Ninh airstrip. Elements of the 2d

Battalion, 28th Infantry, commanded by Major Louis C. Menetrey, and

two batteries of artillery were moved to

- [47]

- the airstrip. The 1st

Battalion, 26th Infantry, and the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, were

moved to Quan Loi, from where they could be committed as the situation

developed.

-

- By 1215 the 1st Battalion,

18th Infantry, had made contact with a Viet Cong company. This

engagement, the first. of six major firefights that comprised the

battle of Loc Ninh, resulted in another twenty-four enemy soldiers

killed. At 1215 the following day the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry,

again made contact, and the 273d Viet Cong Regiment lost eighty-three

men. At 0055 hours on 31 October, the 272d Viet Cong Regiment made its

bid from the northeast for the Loc Ninh district headquarters and the

CIDG compound, now reinforced with elements of the 2d Battalion, 28th

Infantry, and Battery A, 6th Battalion, 15th Artillery. The 272d

Regiment withdrew at 0915, leaving 110 bodies and 68 weapons around

the airstrip. To block the withdrawal of the 272d Regiment, the 1st

Battalion, 28th Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James F.

Cochran, III, conducted an air assault three kilometers southeast of

the airstrip. Although the battalion made sporadic contact for several

days following the assault, it was unable to re-engage the enemy

significantly. While the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, blocked the

southwest withdrawal route of the 272d Regiment, the 1st Battalion,

18th Infantry, searched the area west of the airstrip.

-

- In the early morning hours of

2 November, the night defensive position of the 1st Battalion, 18th

Infantry, became the battlefield for the fourth major engagement of

the battle for Loc Ninh. The 1st Division's after action report

described the conflict as follows:

-

- 2 Nov-The 1 /18th Infantry NDP

[night defensive position] came under heavy mortar attack commencing

at OO80H and lasting for 20 minutes. The mortar positions were

reported by ambush patrols, one being directly south of the NDP and

one being located to the southwest. About 5 minutes later, Company A

ambush patrol reported movement coming from the south. The VC were in

the rubber guiding north along a road which led into the NDP. The

ambush patrol blew its claymores and returned to the NDP. One VC was

KIA [killed in action] attempting to follow the ambush patrol inside

the NDP.

-

- To the east, Company D's

ambush patrol reported heavy movement and the patrol was ordered to

return to the perimeter. Company C ambush patrol located north of the

NDP also reported movement. The patrol blew its claymores and returned

to the NDP. The VC attacked the NDP from three sides, northeast, east

and south. Artillery and mortar defensive concentrations served to

blunt the assault. Two VC armed with flamethrowers were killed before

their weapons could be fired.

-

- As the artillery was brought

in close to the NDP from one direction, the VC fire would diminish and

build up from another direction.

-

- When LFT's [helicopter light

fire teams] arrived on station they were directed to expend on the

main attacking force to the south. The gunships as well as the FAC

[forward air controller and the AO [aerial observer] received heavy

machinegun fire from three locations to the south. Fire from 12

- [48]

- heavy machineguns was

identified. Airstrikes eliminated the positions. The artillery battery

inside the NDP was directed to be prepared to fire antipersonnel

rounds. The guns were readied but their use was not required.

- Contact was broken at

0415H. U.S. casualties were 1 KHA [killed hostile action] and 8 WHA

[wounded hostile action. There were 198 VC KIA and 22 KBA [killed by

air] by body count in the immediate vicinity of the NDP. For the next

five days patrols found additional VC bodies bringing the final body

count to 263 VC KIA (BC) [body count] and 6 POW's [prisoners of war].

There were 18 individual weapons, 10 crew served weapons, and 3

flamethrowers captured. The flamethrowers were Soviet Model . . . .

The unit was identified as the 273d VC Regiment. There were 50 sorties

of tactical air flown in support of the contact.

-

- November 2d was the fifth day

of the battle for Loc Ninh. The enemy had attacked Loc Ninh twice and

had been defeated both times. The U.S. battalions blocking his retreat

were deployed on the southeast and southwest withdrawal routes.

Intelligence indicated that it was now time to close the escape routes

to the north. The 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry (attached to the

division for this operation), and the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry,

were assigned the mission. The 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry, commanded

by Lieutenant Colonel Raphael D. Tice, air-assaulted seven kilometers

northeast of Loc Ninh; the 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, commanded by

Lieutenant Colonel Arthur D. Stigall, landed six kilometers northwest.

The landings were unopposed, and both battalions established night

defensive positions in the vicinity of their landing zones. The four

corners of the square were now occupied by U.S. battalions, each

supported by carefully positioned artillery batteries. At 2340 eight

Viet Cong walked into the 2d Battalion, 12th Infantry, position, half

of them carrying flashlights. Four of the enemy were killed and four

were captured. They were members of the 272d Viet Cong Regiment. The

U.S. battalion's position was attacked at 0220. When the fight was

over, twenty-eight enemy bodies were left around the perimeter.

-

- The final engagement of the

battle for Loc Ninh occurred on 7 November, when two companies of the

1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, engaged the 3d Battalion of the 272d

Viet Cong Regiment. The 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, had been

airlifted out of the area on 6 November after having spent four days

northwest of the airstrip without a significant contact. The battalion

air-assaulted into an area two kilometers west of the 2d Battalion,

12th Infantry-roughly eight kilometers northeast of Loc Ninh. The day

after the air assault, Companies C and D and Colonel Stigall's command

group engaged the 3d Battalion, 272d Regiment. Artillery, armed

helicopters, and twenty-seven air strikes supported the U.S. troops.

Ninety-three enemy soldiers were killed, including twenty-seven by air

strikes. The battle of Loc Ninh was over.

-

-

Of the six major engagements

that comprised the battle of Loc[49]

SERGEANT AND RIFLEMAN ENGAGE

ENEMY WITH MI6 RIFLES-

- Ninh, two were fought in

temporary night defensive positions. The use of night defensive

positions in Vietnam was brought about by the lack of conventional

front lines, the inclination of the enemy to fight at night, and the

need for the tactical units to protect themselves. The principles of

defense were unchanged from earlier wars, but their application to

night defensive positions included a number of new techniques. The

most widespread of the innovations was the increased emphasis on

defensive operations throughout the Army-an army that has been and

will probably continue to be oriented to the attack, rather than to

the defense. Companies and battalions in previous wars had been

integrated into the defensive plans of larger units to a far greater

extent than was possible on the battlefields of Vietnam. The

independence of these units required a new emphasis on all aspects

of defensive operations by company and battalion commanders. For

example, in the past a battalion commander in a defensive position

on the forward edge of a conventional battle area could expect the

brigade headquarters to deploy a security force in front of his

position. He could also expect additional forces in the form of a

general outpost to be deployed forward of the brigade's outposts.

The battlefield in Vietnam, however, was not adaptable to these

traditional arrange-

- [50]

- ments, and the extensive

security echelons that characterized the night defensive positions in

Vietnam were the sole responsibility of the battalion or company

commanders who organized the positions.

-

- The principles of defense were

professionally applied to the night defensive positions at Loc Ninh.

In the 2 November attack on Colonel Cavazos' night position, one

American was killed and eight were wounded. The enemy body count was

263. Among the primary factors that contributed to these and other

similarly impressive results was the position that had been

standardized in the 1st Infantry Division.

-

- During SHENANDOAH II the VC

attacked a night defensive position on five separate occasions: 6

October, 11 October, 31- October, 2 November and 3 November. The US

KHA [killed hostile action] totaled seven. The VC KIA was 509 by body

count. One of the major reasons why the friendly casualties were so

low was the 1st Infantry Division fighting position. This fighting

position has become standardized throughout the division and provides

each soldier with adequate overhead cover, overhead clearance, and

protective berm to the front with firing apertures at a 45 degree

angle a berm to the sides, adequate near protection and thorough

camouflage. The fighting position is completed during the first day in

a new NDP, before the soldier is allowed to sleep.

-

- A second factor that

contributed significantly to the effectiveness of U.S. units in

Vietnam was new weapons. The M16, the standard rifle, took eight years

to progress from the drawing board to combat in the U.S. Army. It was

designed by the Armalite Division of Fairchild Aircraft Corporation in

1957 and sent to Vietnam with the 173d Airborne Brigade in 1965.

Initially the rifle was the target of some criticism because sometimes

it would unexpectedly stop firing. Technical modifications were

therefore made on the weapon. These improvements, along with a

significant effort to train the troops in its care and cleaning,

removed any doubts about the reliability of the M16 in combat. The M16

muzzle velocity was higher than that of its predecessor, the M14,

which significantly increased the destructiveness of the bullet at

close range. The relatively light weight of M16 ammunition (half the

weight of the 7.62-mm. NATO round) allowed the soldier to carry a

larger basic load and reduced the frequency of resupply. The M16 was

dependable, easy to maintain, and capable of being fired as either a

semiautomatic or automatic weapon. It proved particularly valuable in

the jungle where visibility was poor, targets were fleeting, and

contact was normally at short range.

-

- The history of the M79 grenade

launcher is longer than that of the M16, but it too first met the test

of combat in Vietnam. Development of the 40-mm. M79 began in 1952;

however, it was not until 1961 that a substantial quantity was

available for issue to units. With the M79, units in Vietnam could

engage the enemy with a fragmentation round beyond normal hand grenade

range. High explosive was the

- [51]

CLAYMORE MINE, ARMED AND

READY TO FIRE-

- most commonly used round,

although other types of ammunition were available. The M79 was useful

in conducting ambushes and counterambushes; destroying point targets,

such as machine gun positions; providing illumination; and marking

targets for air strikes. The weapon was a universal favorite with U.S.

troops in all units from infantry to quartermaster.

-

- These small arms and support

weapons were coupled with night surveillance devices to give U.S.

units a significant advantage over the enemy in night operations. The

night surveillance devices most commonly used in Vietnam were the

searchlight, sniper-scope, starlight scope, and radar. Among these, the

innovation was the starlight scope. This device weighs only six pounds

and, when mounted on an M16 rifle or M60 machine gun, can fire

effectively at night out to 300 meters. The principle of the starlight

scope is amplification of existing light. In situations where no

natural light was available for the starlight scopes, artificial

illumination from searchlights, flares, and other light sources was

used. In addition to the individual model, larger crew-served

starlight scopes were also manufactured.

-

- Other new equipment related to

night defensive positions was also introduced in Vietnam.

Anti-intrusion devices, such as various types

[52]

- of sensors, supplemented the

security echelons at night. Kits including fortification material and

mortars that could not be carried cross-country were delivered and

removed from unit night positions by helicopter. The claymore mine

became a part of virtually every night position in Vietnam.

-

- The claymore mine, which was

developed by the U.S. Army before the war, was introduced into combat in

Vietnam. The mine weighs 3.5 pounds and has a casualty area the height

of a man out to fifty meters. Most importantly, it can be aimed to cover

a specific area. In fixed positions claymore mines were used in depth,

with overlapping kill zones. In ambush positions the ratio of one mine

to two men was not uncommon. The claymore mine was particularly

effective to open an ambush because the extensive, instantaneous kill

zone that it generated did not disclose the location of the ambush

patrol. The ingenuity and speed with which claymores were positioned

became a matter of professional pride with infantrymen in Vietnam. The

mine's effectiveness has insured its retention in the U.S. Army's

arsenal.

-

- Many of the problems encountered

were unique among the recent experiences of artillerymen, and the

solutions to some of these problems were necessarily innovative. The

classic artillery roles remained unchanged, but how the units were used

often differed from previous wars. Because of the large areas that

needed protection and the enemy's surprise tactics of ambush, raid, and

attack by fire, artillery units were required to respond almost

instantly to calls for defensive fire, Any U.S. or allied installation

without this support was inviting attack by the North Vietnamese Army

and Viet Cong. Such instant response required spreading the artillery

thin and resulted in the inability to mass fire, as was done in World

War II and Korea. Large amounts of firepower were delivered, but instead

of firing a few rounds from many weapons- as was the case in more

traditional warfare-many rounds were fired from the few tubes within

range of the target.

-

- The "speed shift" of

the 155-mm. howitzer was an example of the ingenuity of artillery

innovations in Vietnam. During the first few months of Vietnam combat,

1st Lieutenant Nathaniel W. Foster of the 8th Battalion, 6th Artillery,

1st Infantry Division, developed a simple, effective device to allow

rapid shifting of the 155-mm. towed howitzer. The old method involved

lowering the weapon down off its firing jack, picking up the trails, and

pointing the piece by hand in the new direction of fire. At best, this

action was a time-consuming procedure involving considerable effort for

at least eight men. Under less-than-ideal conditions, particularly in

mud, such a shift was accomplished only with tremendous difficulty. This

problem considerably hampered the ability of the 155-mm. towed units to

meet the 360-degree firing requirement that existed in Vietnam.

- [53]

- The solution to the

problem was a locally fabricated "pedestal" positioned under

the howitzer carriage at the balance point. In use, the howitzer was

lowered until its weight rested on the pedestal. It was then possible to

pick up the trails and swing the howitzer in any direction in seconds,

The average crew strength was six. Because of its effectiveness, the

speed shift pedestal came into general use within the 8th Battalion, 6th

Artillery, in the spring of 1966. In Operation BIRMINGHAM, Battery B,

with Lieutenant Foster as its executive officer, fired over 7,200 rounds

during nineteen days and performed innumerable shifts using the

pedestal. One gun was shifted thirty-three times in one critical

nineteen-hour period.

-

- A new response to the need for

heavy artillery was the 175-mm. gun, which was used in combat for the

first time in Vietnam. The gun was a corps-level weapon and could

permanently cover large tactical areas of operations, thus freeing the

smaller caliber division artillery units to support the maneuver units.

Furthermore, the 175-mm. gun when teamed with the reliable eight-inch

howitzer was even more effective.

-

- Central tactical control of all

field artillery units was exercised in Vietnam to insure the most

efficient use of available firepower. However, an artillery mission was

generally carried out at the lowest possible level, usually battery or

platoon. Brigadier General Willis D. Crittenberger, Jr., Commanding

General, I Field Force Artillery, described the situation as follows:

-

- This war, at least from the

Force Artillery point of view, is largely a battery commander's war-the

junior officer must really be on his toes, thinking ahead, making his

wants known in advance, for his battalion staff is miles away. In

addition, the various fire support bases are established in several

locations, so one can cover another. The battery commander then must be

self-reliant. Vietnam is a great training ground for the leaders of the

future.

-

- Unique problems that arose from

the unconventional nature of the war in Vietnam were, of course, not

limited to artillery. Tactical control measures were also a major

difficulty. One geographical area in Vietnam might well contain American

tactical units; third country forces; Vietnamese regular tactical units;

American Special Forces detachments; and irregular units, such as

Regional Forces, Popular Forces, and People's Self-Defense forces. Clear

boundaries were needed between these units to avoid the tragic

consequences of friendly fire landing on allied positions. At the same

time, unity of command was required to insure that friendly units,

regardless; of make-up or nationality, were reinforced in the shortest

possible time when necessary.

-

- In the spring of 1967, the II Field Force

commander, Major General Frederick C. Weyand, introduced a new solution

to the tactical control problem. In

co-ordination with the Vietnamese III Corps

- [54]

-

GENERAL WESTMORELAND AND

GENERAL HAY

commander, he divided the zone

into "tactical areas of interest" and assigned them to

subordinate commanders. These tactical areas of interest were normally

extensions of the tactical area of responsibility. In the tactical

areas of interest, commanders were not charged with primary tactical

responsibility, and they were not expected to conduct operations on a

continuing basis. The commander to whom a tactical area of interest

was assigned, however, had to know the location, activities, and

operations of all forces and installations in his area and, through

mutual co-operation and co-ordination, to achieve the maximum effect

from the combined friendly forces and firepower available. This

arrangement worked extremely well. Not only did it provide local unity

of command, but it served to increase the confidence and

aggressiveness of the Vietnamese Army commanders who shared areas of

operation with U.S. tactical elements. The Vietnamese commanders knew

that their U.S. counterparts would provide resources and firepower

when they needed them.

- [55]

- Brigadier General Henry J.

Muller, Jr., served in Vietnam on both sides of this arrangement. As

assistant division commander of the 101st Airborne Division, he

participated directly in providing support, primarily helicopters and

firepower, to the commanders of the 1st ARVN Division. Later, he became

the deputy senior adviser to the Vietnamese I Corps commander,

Lieutenant General Lam. In this capacity he co-ordinated support to I

Corps from the 101st Airborne Division and other U.S. units. He

attributed the remarkable progress of the Vietnamese divisions in the I

Corps area primarily to the close association between the Vietnamese

units and the U.S. tactical elements in their common operational area.

-

- The key innovation of Loc Ninh

was the exploitation of the tremendous tactical mobility available to

the 1st Infantry Division. When the battle started with the attack on

the airstrip, there were no regular U.S. Army units around Loc Ninh.

Immediately the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry, most of the 2d Battalion,

28th Infantry, and two batteries of artillery were committed. Two more

battalions were standing by twenty kilometers south at Quan Loi, ready

to be flown in by helicopter on a few minutes' notice as the situation

developed. On 2 November, the fifth day of the battle, two additional

battalions stationed 100 kilometers to the south were flown in and

attached to the 1st Infantry Division. This ability to react with entire

battalions and their supporting artillery on short notice and the

concomitant ability to withhold the battalions until the enemy has

committed himself were major innovations of the war.

-

- Such unprecedented mobility

coupled with the firepower available to 1st Division commanders laid the

foundation for the victory at Loc Ninh. Time-tested principles, new

weapons, starlight scopes and other surveillance devices, claymore

mines, responsive artillery, and innovative tactical control measures

all contributed. Finally, the individual soldier, well trained and well

led, was the decisive factor. In the words of General Westmoreland at

the conclusion of the battles around Loc Ninh: "This operation is

one of the most significant and important that has been conducted in

Vietnam, and I am delighted with the tremendous performance of your

division. So far as I can see, you have just made one mistake, and that

is you made it look too easy."

- [56]

- page created 15 December 2001

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents