CHAPTER XIX

Establishing the Iceland

Base Command

The hot and hectic summer of 1941 was drawing to a close when, toward the end of August, men and cargo for the Second Echelon of the Army's Iceland task force began arriving at the staging area of the New York Port of Embarkation. The sailing date had been set between the first and the fifth days of September. By 4 September some 5,000 troops of the 10th Infantry Regiment, the 5th Engineers, the 46th Field Artillery Battalion, and various service units had arrived and were ready to embark. Throughout that day the men moved to the port, boarded the four troopships- Heywood, William P. Biddle, Harry L. Lee, and Republic- and at 8 o'clock the next morning, 5 September 1941, the convoy got under way. Guarded through coastal waters by vessels of the First and Third Naval Districts, the transports and accompanying freighters on the following day picked up their ocean escort and destroyer screen at a meeting point off the coast of Maine.1 on the evening of 11 September they were ploughing through the North Atlantic somewhere south of Greenland when the voice of President Roosevelt came over the radio announcing an attack on the USS Greer -he called it piracy-and declaring that German or Italian vessels of war would henceforth "at their own peril" enter waters essential to the defense of the United States. The convoy at this moment was skirting the strongest concentration of submarines the Germans had as yet assembled in the North Atlantic, which for two days past had been raising hob with a large Anglo-Canadian convoy to the northward. Although the American convoy had its route changed several times in an effort to avoid the scene of action, seven U-boats were picked up by the

[494]

destroyers' sound gear and one submarine was attacked "under favorable circumstances." Four days later, during the night of 15-16 September, the convoy reached Iceland safely.2

In Reykjavik, awaiting the convoy's arrival, were two officers of General Bonesteel's command: Lt. Col. Kirby Green, the force G-1, and Lt. Col. Matthew H. Jones, the quartermaster, who had gone on ahead to work out the landing arrangements. By coincidence, the vessel they had traveled on was the Greer. They had been on board at the time of the attack and had arrived in Iceland on the same day the Second Echelon sailed from New York.

The Movement of the Second Echelon, Task Force 4

The movement of the Second Echelon had been carefully studied and observed by officers from GHQ so that the experience gained might be preserved for the benefit of future operations. A comparison with the movement of the First Echelon revealed improvement in operational planning. During the loading of the First Echelon in July, cargo had arrived at the port in helter-skelter fashion and was stowed just as it came in. It had been, in the words of Colonel Morris, commanding officer of the First Echelon, "a remarkable piece of delirium." 3 Cargo for the Second Echelon was, for the most part, assembled before the vessels were ready to load. More complete data concerning shipments were made available to the port authorities and to force headquarters before the actual loading commenced, and it was generally agreed that operations proceeded more smoothly than those of the First Echelon. Nevertheless, according to Brig. Gen. Homer M. Groninger, commander of the New York Port of Embarkation, there were still too many last-minute changes and orders from too many sources. Members of the headquarters staff arrived before loading started and stayed throughout the operations, but had they come a week earlier the ships could have been worked that much sooner. Although the delay did not postpone the scheduled sailing, it did tie up transportation facilities at the port longer than necessary.4

Unloading operations at Reykjavik were better planned and more closely

[495]

supervised than those of the First Echelon. So that the problem could be studied during the voyage, General Bonesteel's headquarters had been provided with cargo manifests as soon as the convoy sailed; while, in Iceland, a preliminary plan of discharge was sketched out by Major Whitcomb, who had been the quartermaster representative in Iceland since early July. Major Whitcomb, a Reserve officer, whose attitude toward superior rank was at first a source of astonishment to a polished, well-schooled professional like General Bonesteel, was a man of considerable ability in his own particular field of port operations and of abundant energy in many directions. His plan was the basis for the arrangements made by Colonels Green and Jones. In summary, it provided for the following: the two vessels loaded with the most vehicles were to be berthed alongside the piers first; after them the vessels with the most nonperishable stores were to be docked; and last of all the vessels with perishable supplies. Cargo vessels that were waiting their turn to dock and the troopships, which were too large to enter the harbor, were to lighter their cargo to the piers by covered tenders and land their vehicles on nearby beaches by tank lighters. Personnel were to disembark by boats and tenders, preferably to one of the beaches, and if not there, to the Reykjavik piers. Whitcomb was insistent that the open tank lighters not be used to land general cargo, for this was before the days of waterproofed cartons.5

As soon as the Second Echelon arrived, General Bonesteel called a conference at his headquarters on board the transport Republic to decide upon the details; but, when it came to carrying out the actual operations, much of the planning gave way to improvisation. Two of the cargo vessels, carrying about 60 percent of the vehicles, the lighter vehicles, were docked pretty much according to plan and discharged their cargo directly to the pier. But with the Navy insisting importunately upon a speedy turnaround, every type of craft that could be found was pressed into service to discharge the four troop transports and the other two cargo vessels that lay outside the harbor. Tank lighters and landing craft, and motor launches belonging to the naval escorts, and one of the Icelandic fishing vessels, were all employed to transfer cargo of every sort to the docks. Even the Norwalk, a former American coastwise vessel, small and rather shallow draft, that had arrived in Iceland with supplies about a week before the convoy, was put to use transferring cargo from the Republic. Motor vehicles were lightered ashore to the beaches, but all the other cargo and all personnel were landed at the docks. The port company

[496]

GALE IN ICELAND

that had arrived as part of the First Echelon was too small to do the job and the troops of the Second Echelon were inexperienced. High winds, heavy seas, and pouring rain almost constantly hindered operations and at times forced a complete halt. As Whitcomb had feared, cartons that through lack of tarpaulins had been soaked by rain and spray spilled their contents on the docks, and the result was considerable loss and some pilfering. By 25 September the troop transports and the two vessels at the docks had been completely unloaded and half the vehicles on board the other two cargo vessels had been landed. 6 During the nine days, 9,746 tons, by weight, of general cargo and 511 vehicles, weighing about 1953 tons, were discharged. All troops disembarked on 24-25 September, and work was commenced on the

[497]

two remaining cargo vessels with a much reduced labor force. On 3 October the last box came ashore. Some 5,000 men, with 15,390 dead-weight tons of general cargo and 641 vehicles weighing 2,717 tons, had landed on the island.7

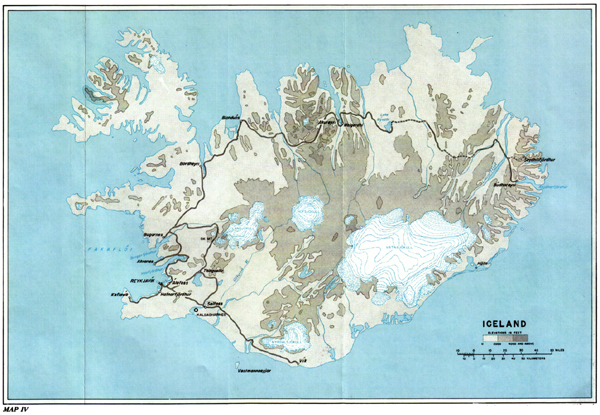

General Bonesteel established his headquarters at Camp Tadcaster, soon renamed Camp Pershing, some two miles east of Reykjavik and about a mile from British headquarters at Camp Alabaster. The troops were concentrated principally in five or six camps in the neighborhood of Alafoss, eight or ten miles northeast of the force headquarters, in locations fixed primarily by the availability of land and existing facilities and featured by the lack of first-class roads. (Map IV)

Problems of Defense: Ground and Air

The whole matter of defense was complicated by Iceland's varied, never gentle topography. The island is large, roughly oval in shape, with a bare and desolate clawlike peninsula jutting out to the northwest. Its area of about 39,700 square miles is nearly that of Kentucky or Virginia and somewhat larger than that of Indiana. A rugged interior plateau, partly covered with great snow fields and glaciers and capped by a chain of volcanic mountains that rise to a height of almost 7,000 feet, dominated the tactical problem as it does the island itself. In the southwest there are two low-lying coastal plains, one at the head of Faxaflói and the other between the river Ölfusá and Mýrdalsjökull. From them, narrow river valleys lead up into the central tableland, and elsewhere around the coast deep fjords, separated by rocky promontories, penetrate some twenty miles or more into the interior. In the coastal lowlands and river valleys, comprising scarcely 7 percent of the entire area, most of the island's 120,000 inhabitants lived in scattered hamlets or on isolated farms. Reykjavík, with a population in 1941 of 39,000, was the only fair-sized city as well as the capital. Akureyri, on the northern coast, was second in size with a population of only 5,300. Communications across the barren central plateau were, in 1941, limited to one dubious road, frequently snowblocked in winter, that ran across the base of the western peninsula. Around the island there were stretches where roads were entirely lacking. 8

[498]

ICELAND

The British had provided for the defense of Iceland by sectors. Under the plan then current, the island was divided into five sectors, four of which contained areas of strategic importance requiring ground, antiaircraft, and coastal defenses. The Southwestern Sector, comprising the Reykjavík-Keflavík Peninsula area, was the smallest but most important. To its defense, the British had assigned some 10,500 troops. In the Western Sector, immediately adjoining, about 7,300 troops covered the land and air approaches to Reykjavík and manned the defenses of the naval anchorage in Hvalfjördhur and the airfield at Kaldadharnes. Thus, about 70 percent of the entire British garrison was stationed within a thirty-mile radius of the Reykjavik docks. The North western Sector was so organized as to protect the only road connection with the north coast, on a line running from Borgarnes in the south to Blönduós in the north, and for this purpose some 1,350 troops were assigned to the sector. Eastward from Blönduós a road led to the port of Akureyri. Beyond Akureyri a road of sorts extended about 60 miles to Lake Mývatn, but after that land communications became virtually nonexistent. Except for short stretches in the extreme eastern end of the island near Seydhisfjördhur and Búdhareyri and equally short stretches on the southern coast, roads became mere bridle paths and even these disappeared in places. The Northeastern Sector therefore comprised two widely separated centers of defense relatively inaccessible to each other and epitomized this aspect of the defense problem of the whole island. Some 3,500 men were stationed in the neighborhood of Akureyri for the protection of the port and seaplane anchorage and for the defense of the landing field at nearby Melgerdhi. Another 1,800 troops were assigned to the Northeastern Sector and stationed in the Seydhisfjördhur Búdhareyri area, which included a potential landing place for seaplanes on Lagarfljót (Lake Logurinn). These four sectors accounted for the whole of the British garrison, approximately 24,400 men; for no troops were assigned to the Central Sector, where a descent by hostile forces upon the mountainous wastelands or on the barren coast would have been difficult and led no where. 9

The British scheme of defense assumed that the threat to be guarded against was an invasion of the island, an operation which Hitler had considered in June 1940 as a preliminary to the invasion of Britain, but which the German naval staff had flatly and successfully opposed. Iceland was,

[499]

however, just within range of German bombers in Norway, and the Bismarck's foray into the Atlantic had shown what might happen if Hitler transferred other units to Norwegian bases, as he constantly suggested doing.10 If a large-scale invasion seemed hardly possible, particularly after the start of the Russian campaign, a "hit and run" assault by air or naval raiders appeared to be distinctly probable. Because of the topography, defense against this contingency required a sizable garrison; and in any event the more remote but possible contingency could not be entirely ignored. To those responsible for carrying out the mission of defense, the garrison, for this reason, seldom seemed adequate. In June, during the early planning, the question of additional air strength had been raised, and partially to fill this need the 33d Pursuit Squadron had been sent to Iceland. In the course of the summer, while plans for the relief of the British garrison were in progress in Washington, that same garrison was being reinforced with additional troops from England. In August, a Marine Corps study concluded that under existing circumstances a major landing attack on Iceland appeared to be improbable and that the combined naval forces of the United States and Great Britain available in the area, coupled with a strong air force in the same area, should be able to block any German attempt without the intervention of shore defenses; but that, should the existing military and naval situation change radically to the disadvantage of the United States and Great Britain, an adequate defense of the island would require five reinforced infantry divisions, four pursuit squadrons, two bomber squadrons, two attack squadrons (seaplanes), one patrol squadron (PBY's), and appropriate naval defense forces.11 The alternative to a perimeter defense with strong ground concentrations at a few obvious invasion targets was, perhaps, an overwhelming air force capable of sweeping wide off the coast to intercept an invader; but in 1941 the planes were not to be had, air base facilities in Iceland were inadequate, and the lessons of the war in the Pacific were still in the future. Considering the terrain, the poor communications, the assumption concerning the nature of the threat against the island, and the resources available for defending it, the British plan doubtless provided the most feasible defense.

GHQ took a similar approach. The most striking difference between the British plan and the Operations Plan drawn up by GHQ as a guide for the American forces lay in the disposition of the ground troops. The GHQ plan

[500]

assigned 21,131 troops, about 82 percent of the total planned garrison, to the Reykjavik sector; 1,372 to the Borgarnes-Bordheyri-Blönduós area; 1,555 to Akureyri; and 1,638 to the Seydhisfjördhur-Reydharfjördhur area. This was a much greater concentration in the Reykjavik area, compared to the British arrangements, and a much thinner spread of strength in the northern and eastern parts of the island. The explanation was doubtless to be found in the provisions concerning the air garrison. The air units provided in the GHQ Operations Plan -the 33d Pursuit Squadron, 9th Bomber Squadron (H), and 1st Observation Squadron- were not much greater in strength than those of the British; but the difference was that the American air units were to be assigned their mission by the Commanding General, Iceland Base Command, were to operate under his direction, and were specifically charged with the support of the ground troops. The primary mission of the RAF in Iceland was, on the other hand, the protection and covering of transatlantic convoys.12

Shortly after General Bonesteel's arrival, General Curtis, commander of the British garrison, outlined his strategic and tactical views to General Bonesteel. The key to the defense of Reykjavík, as General Curtis saw it, was the Vatnsendi Ridge, five or six miles back of the city, which commanded the roads north to Alafoss and Hvalfjördhur, south to the small port of Hafnarfjördhur and the Keflavík Peninsula, and eastward along the road to Kaldadharnes and Selfoss. Control of the ridge, according to the British commander, would permit rapid counterattack in any of the three directions. From its position around Alafoss, the American mobile reserve was most suitably located for action in the direction of Hvalfjördhur; but should the British reserve behind Vatnsendi Ridge be forced to move out to counter a threat froth the eastward, the American troops, General Curtis continued, should then be prepared to take the place of the British in support of the ridge.13 The major responsibility of the American force would clearly lie, however, in the area to the north and northwest, toward Hvalfjördhur.

How this responsibility was to be exercised was for General Bonesteel to decide. Neither the GHQ Operations Plan, being a guide and not a rule, nor the general's instructions specified his relationship to the British garrison and its defense arrangements, except to provide that he should act in "mutual cooperation" with them. No limits had been established within which the

[501]

two forces were to co-operate; and except for a general understanding that the American force would be initially assigned to the Reykjavík area, no definite bounds within which the American force was to operate had been laid down. These were matters to be worked out by the two generals and their staffs.

After discussions with the British, General Bonesteel defined the specific mission of the American forces as the defense of an area lying within a line that began at the small hamlet of Hvítárvellir, at the head of Borgarfjördhur, and ran along the coast of Gufunes, just outside Reykjavík, thence south to a point on Vatnsendi Ridge, then generally northeast along the shore of Thingvallavatn Lake through the village of Thingvellir, north to Ok Mountain, and finally back again to the coast at Hvítárvellir. The area straddled the boundary between the Western and Northwestern Sectors of the British. Outside the American defense area, antiaircraft units of the marine brigade were stationed alongside British units for the defense of the airport and harbor at Reykjavík; within the area, British units participated in the antiaircraft defense of Hvalfjördhur. The task of guarding the coast line was assigned to the marines, with the 10th Infantry held in reserve. Hvalfjördhur, important as a naval base, was in the middle of the area to be defended; but there was no convenient way of stationing the mobile reserve there. The road along the coast from Reykjavík was very poor and the shores of the fjord extremely rugged. As it was, the reserve had to be stationed in the southern part of the sector twenty or thirty miles from Hvalfjördhur and almost as far as that again from Hvítárvellir.14

Some 26,800 British and American ground troops, or about 80 percent of the total of the two forces, were available for the defense of the Reykjavík-Hvalfjördhur area. Although this was a larger number than the ground defenses fixed by the GHQ Operations Plan for the entire island, General Bonesteel considered it inadequate. He estimated, in reply to a radio from GHQ on 21 October 1941, that in view of the war situation the defense of the Reykjavik area would require some 39,800 troops, including the general reserve to be based there, and that the total garrison necessary for defending the entire island should be about 67,000 troops.15 Whatever were the theoretical needs, the fact was, as General Bonesteel nevertheless

[502]

recognized, that the countryside about Reykjavik was approaching the saturation point in the matter of accommodating troops; for within a dozen miles of the city there were crowded nearly a hundred camps and installations ranging upwards in size from platoon strength.16

Much the same situation prevailed with respect to the air garrison. The British had, based on Reykjavík, one squadron of 15 Wellington bombers, a flight of 8 or 9 Hurricane fighters, a Norwegian squadron of 6 Northrop reconnaissance float planes, and 30 utility planes. These had been augmented by the 33d Pursuit Squadron (U.S.) with an original combat strength of 30 planes. At Kaldadharnes, about thirty-five miles southeast of Reykjavík, there was a British squadron of 26 Hudson bombers and 2 utility planes. A detachment of the Norwegian reconnaissance squadron, consisting of 4 planes, was at Akureyri, and another of 3 planes at Búdhareyri. In addition there was a United States naval air unit operating patrol planes out of Reykjavík. The total air strength, like the ground forces, was greater than that called for in the GHQ Operations Plan, but it too seemed inadequate. Only the 33d Pursuit Squadron was under the control of the Commanding General, Iceland Base Command; and the only planes available for medium-range reconnaissance in support of ground troops were those of the Norwegian squadron, whose primary mission, like that of the other bombers and reconnaissance planes, was offshore patrol.17 In September Brig. Gen. Clarence L. Tinker made an inspection of air facilities in Iceland, before assuming his duties as Commanding General, III Interceptor Command, and upon his return to the United States he recommended to GHQ that additional bomber and reconnaissance strength be allotted to General Bonesteel. The latter placed his requirements at one squadron of heavy bombers, one of light bombers (A-20 type), one long-range reconnaissance squadron, one medium-range, and the entire 8th Pursuit Group, to which the 33d Pursuit Squadron, already in Iceland, belonged.18 But again, as in the case of the ground defenses, tactical requirements had to give way to physical limitations as the basis for determining the strength of the garrison.

The existing airfields at Reykjavík and Kaldadharnes, jointly used by

[503]

the RAF and Americans, were overcrowded and unsuitable for heavy bomber (B-24) operations. Dispersal areas for the planes and housing for the men were limited. Runways, hastily built in the first place, had rapidly deteriorated under constant use and heavy frosts; and on one occasion a B-24 of the Ferry Command that had parked overnight on the runway at Reykjavík was found, next morning, to have broken through the paving.19 Overcrowding was the chief problem. It was possible to develop Reykjavik airfield only to the extent of taking care of an additional light bomber squadron; by building more parking and disposal areas at Kaldadharnes, and by providing housing, another squadron could be accommodated there.20

The solution recommended by both General Bonesteel and General Tinker, and eventually adopted, was to construct an entirely new airfield, suitable for heavy bombers, in the neighborhood of Keflavík. Tests and surveys conducted under the direction of Colonel Morris, commander of the First Echelon and of the Iceland Base Command's air force, had already established the feasibility of constructing an additional fighter field there. The two projects would obviously complement each other. As soon as GHQ approved the idea of a bomber field early in November, the Iceland Base Command engineers began surveying the proposed site; but not until 29 December, three weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, was the Iceland Base Command authorized to go ahead with the preliminary clearing and grading. Even then the arrangements for acquiring the land had not yet been completed.21 The two fields ultimately built at Keflavík, the bomber field (Meeks Field) and its satellite (Patterson Field) became the principal American air base in the North Atlantic and an important link in the ferry route to England; but this was in the future. Meanwhile, the problem of air defense in the fall of 1941 remained.

Since accommodations could not be provided for what he considered the full requirements, General Bonesteel fixed the immediate needs at one light bomber squadron, to be based at Kaldadharnes as soon as housing

[504]

became available, arid pursuit plane replacements sufficient to bring the 33d Pursuit Squadron up to its original strength. Washington approved the delivery of spare parts to Iceland so that planes not completely wrecked could be put into commission, but made no move to send the planes. Then, in late October the War Department learned that the British were proposing to withdraw their flight of Hurricane fighters from Iceland and that the United States Navy was contemplating sending a squadron of bombers for winter operations out of Reykjavík. The one brought into question the adequacy of Iceland's fighter strength; the other posed the problem of paramount interest between Army and Navy.22

Against the possibility of determined "hit and run" bombing attacks, which was accepted as the basic assumption, Iceland's fighter defenses seemed woefully weak. Germany had from 60 to 90 long-range bombers capable of reaching Reykjavík and returning to their bases in Europe. Against this potential striking force, the 33d Pursuit Squadron, by the end of October, could send aloft only about 20 planes, and by 6 December 1941 the number had been further reduced to 12 or 15 planes. Spare parts sufficient to bring the squadron almost up to full strength were on order, but the channels of aviation supply seemed to be full of obstructions. The immediate need, enhanced by the prospective withdrawal of the RAF Hurricanes, induced GHQ to provide reinforcements.23 On 14 November General Arnold gave instructions for 10 pursuit planes to be made ready for shipment to Iceland; and the same day GHQ informed General Bonesteel that a squadron of either medium or heavy bombers would be sent at once. The bomber question was almost immediately reconsidered, however, and at the end of the year the pursuit planes were still in their crates on the New York docks.24

In view of the delay it was indeed fortunate that the dissenting opinion of Maj. Lyman L. Lemnitzer, rather than the majority view of his colleagues

[505]

in GHQ, was borne out by subsequent events. When the question of Iceland's air defenses was under study, Major Lemnitzer had observed that, regardless of the possibilities, Germany was unlikely to launch a determined air attack against Iceland during the coming winter, the winter of 1941-42. Unfavorable weather, targets incommensurate to the risks involved, and the demands of the Russian front would, he pointed out, vitiate an argument based entirely on German potentialities.25 And so it happened; although there were numerous alerts, not a single German plane was sighted over Iceland from 16 December 1941 until early March 1942, when the previous pattern of air activity was resumed. For a while, no bombs were dropped. As before, enemy flights were limited to single planes on reconnaissance or weather observation missions.

There was as great a need for additional radar and aircraft spotting stations and for improved communications between the stations and the control center and between ground and plane in September 1941 two British radar stations were in operation, one about three miles southeast of Reykjavik and the other at Grindavík. Spotting posts were set up along the coast, and by the end of 1941 three more radar stations were put into operation by the British. But it could take as long as an hour and a quarter for a report from one of the distant posts to reach American fighter headquarters. On seven occasions during July and August, and three other times during the rest of 1941, German or unidentified planes were reported over Iceland. Although patrol flights were kept in the air intermittently throughout every day and additional flights sent up when the need appeared, not one of the intruding planes was intercepted.26 Lack of planes and radar equipment and slow communications held the defending planes to arbitrarily established patrol lines and prevented the aggressive search that might have resulted in successful contact.

An Aircraft Warning Service detachment to set up and operate an additional RDF (Radio Detection Finder) station on Vestmannaeyjar, a small island off the southern coast, was requested by General Bonesteel for movement in November; but the matter of troop movements, of reinforcement as opposed to relief of the British, became intertwined with a web of administrative problems inherent in the occupation itself. As a result, the AWS

[506]

detachment did not arrive until 23 December, when the first large-scale reinforcement was made.

Problems of Administration and Human Relations

To bring the garrison up to peak efficiency and keep it there, as well as for morale purposes, General Bonesteel instituted a thoroughgoing program of training, including basic, weapons, and winter warfare. A distinctive feature of the program was the acting officer schools. These were designed to provide continuity of leadership at the platoon and company level should an enemy assault result in heavy attrition among the company grade officers. To this end, specially chosen noncommissioned officers were designated to act as lieutenants, captains, and even field grade officers while on field exercises with the troops.

Quite apart from the problems that related directly to the matter of defense were those that were inherent in the mere presence of American troops on foreign soil. The welfare of the troops, and their relations with the Navy, Marine Corps, State Department representatives, the British, and the local populace involved fundamental questions of human intercourse. Whether in Iceland, Newfoundland, Bermuda, or Trinidad, these problems were much the same.

That the welfare of the men would present a serious problem had been recognized early. Concern over it had been responsible to a very large extent for the insistence upon the American troops being stationed in the vicinity of Reykjavík and it was an important factor in the desire of the Navy Department to bring home the marines as quickly as possible. As in the case of other bases, the principal element of the problem was considered to be the question of recreational facilities. At home the American soldier took his recreation in nearby towns and cities either at his own expense among the general public or in recreation centers operated by private organizations. Governmental responsibility had extended only to sponsoring a consolidation of the various private welfare agencies into the USO. Iceland, however, was, according to American standards, woefully lacking in places devoted to public entertainment; and since the island was held to be within a theater of operations, the USO was by policy excluded. Thus the Army found itself with the responsibility of providing recreation facilities for the troops beyond that normally provided, with what assistance the Red Cross could give. Sixty huts for post exchanges and recreational purposes were ordered within a few weeks after the arrival of the Second Echelon, and the sum of $940,000 was allotted for the construction of six service club build-

[507]

ings.27 But other construction materials were given higher priority by General Bonesteel and the problem of shipping showed no sign of diminishing, so that recreation huts were still lacking in April 1942. Efforts to obtain space in Reykjavik were likewise fruitless. The Red Cross workers who had come to Iceland expecting to set up a canteen and recreational center in the city were thus forced back upon the makeshift arrangements that had been improvised within the various camps. Furthermore, the Red Cross, as an organization, was inexperienced in operating recreational facilities; for relief, not diversion, had been its traditional role. The inevitable aftermath of the situation was, initially, a certain amount of floundering, despite which the Red Cross workers proved their worth many times over.28 Improvement appeared with the summer of 1942; but until then the rigorous training program and hard labor had to serve as a substitute for recreational facilities.

Equally important to the well-being of the troops was the question of the length of the tour of duty in Iceland, and equally long delayed was the solution. While GHQ was considering an inclusive policy applicable to all the other Atlantic bases, Iceland, because combat operations were more in prospect there and because of a more acute "morale problem," was made the object of independent study. Transmitting its findings to G-1 of the War Department General Staff, GHQ on 4 October recommended that a complete turnover of the First and Second Echelons be carried out within fourteen months, and that individuals be relieved thereafter at the end of twelve months' service in Iceland. The War Department was in general agreement that a one-year limit would be desirable and that a decision should be announced promptly. But the deterrent was whether or not transportation would be available. The relief of the first two echelons would require transporting about 800 replacements monthly beginning 1 April 1942; and if the garrison were increased during the spring and early summer to 30,000 men, as contemplated, the average monthly turnover would rise to approximately 2,500 by the following November.29 The Navy Department, whose responsibility it, was to provide transportation, was loath to commit itself so far in

[508]

the future. The Chief of Naval Operations willingly concurred in a general limit of one year's service, but only "until such time as the United States is at war"; and he pointed out that no naval transports were available for transporting personnel to and from Iceland.30 The Army had recently acquired for use as a troop transport to Iceland a small passenger vessel that had been operating in an interisland service in the Caribbean, but the Stratford's limited capacity (350 men) was far below the requirements of the proposed relief policy. More than a month had passed since GHQ called attention to the advisability of announcing a definite policy. General Bonesteel added his urgings to those of GHQ. On 17 November he recommended a flexible tour of duty -one that varied from ten to fourteen months-to ensure against anyone having to spend more than one winter in Iceland.31 But before a final decision could be made, this, like many another matter, was temporarily lost in the smoke of Pearl Harbor.

There were also certain routine services which, if efficiently administered, would conduce to the well-being of the troops. The prompt delivery of mail from home was most important. An adequate supply of palatable rations and well-handled arrangements for paying the men would likewise do as much as anything to keep spirits high and complaints down. Delays in paying dependency allotments to the families of the men were extremely destructive to morale, but this, like certain of the supply arrangements, was something over which the Iceland Base Command had very little control. Mail deliveries and the shipment of perishable foodstuffs to Iceland were, for a while, too haphazard for complete satisfaction. There was some improvement by midwinter: more experience in administering the overseas APO system had been gained; a regular destroyer run between Boston and Argentia, the transshipment point for Iceland mail, had been scheduled; and the local naval commander had become better acquainted with his supply responsibilities under the current INDIGO plan.32 Although it was many months before the troops in Iceland were assured of a reasonably prompt mail service and a supply of special foodstuffs for special occasions, their lot, in this respect, was far better than that of the men stationed in Greenland or at the CRYSTAL outposts. What made the delays less understandable and harder to

[509]

bear for the Iceland garrison was the relative frequency with which ships were arriving.

Considered as an aspect of the morale problem, the pay arrangements that prevailed in the early months of the occupation were thought to be most nearly what the men desired. Local pressure had successfully persuaded the War Department to male use of local currency at all the newly acquired bases in British possessions, but in Iceland, because of morale and administrative problems, the troops continued to receive their pay in American dollars. By February 1942 the "black market" in dollars had become the overruling consideration and the change to krónur payments was made. Although the administrative difficulties that followed were fully as great as those the finance officer had anticipated, the change to local currency had no appreciable effect on the temper of the men. The adverse effect on morale that General Bonesteel and the War Department had expected, and on which their opposition to the use of krónur had rested, failed to materialize.33

As the Newfoundland experience had clearly shown, the matter of pay arrangements was, in its broader compass, one of the ticklish, complicated problems of intragovernmental relationships and international relations. In Iceland, even more than in Newfoundland and the other bases, the attitude of the local government depended upon the commanding officer's conduct of affairs. General Bonesteel's tact and diplomacy, his willingness and ability to understand local problems, were factors in his success.

Early in June 1941, when it was still uncertain whether the Icelandic Government would give its approval to an American defense force, an old plan for liaison with civil governments that had been drawn up as part of the RAINBOW 4 planning in connection with Newfoundland and Greenland was dusted off and suggested by the judge Advocate General's Department as a directive for the proposed Iceland force. Although it was never issued as a directive, its provisions were incorporated into the G-1 Annex to the Theater of Operations Plan drawn up by GHQ. On the assumption that at least the tacit approval of the government and people would be forthcoming, the local civil government was to be "permitted to function normally"; in that case the situation confronting the American force in Iceland would, it was stated, be "similar to that of the American Expeditionary Force in

[510]

France" during the First World War. For the purpose of maintaining cooperation with the Icelandic Government a liaison section of the Force Headquarters was to be established and officers were to be assigned to duty with various agencies of the government. However, failure to co-operate would be taken as a desire to impede the defense and, under the proposal, would have necessitated establishing a military government.34

Fortunately, the unwisdom of the proposed course of action was speedily recognized. Supplementary instructions proposed by the State Department seem to have reflected a justifiable concern that the situation was not properly understood, for, after summarizing Iceland's constitutional relationship to Denmark, the State Department pointedly enjoined all American military personnel to pay due respect to the local institutions, to refrain scrupulously from interfering with the prerogatives of the civil authorities, and to handle through the American consul, Mr. Kuniholm, all matters involving political questions.35 The timeliness of the State Department's advice was confirmed by the stipulations set forth in the agreement of 1 July 1941 between President Roosevelt and the Prime Minister of Iceland. By this agreement the United States promised that its military activities in Iceland would be carried out "in consultation with Iceland authorities as far as possible" and "with the clear understanding that American military or naval forces sent to Iceland will in no wise interfere in the slightest degree with the internal and domestic affairs of the Icelandic people." 36 Although the State Department proposals were not issued as instructions to the Iceland force, the executive agreement of 1 July became a part of the subsequent INDIGO directives. The position of the United States forces vis-à-vis the local government was thus explicitly laid down, but not specifically defined.

The Icelandic Government almost immediately expressed a desire to negotiate a more complete agreement. In the matter of intercourse between troops and townspeople there was, as the local government surveyed its experience with the British garrison, an unlimited area of difficulty that had both an economic and social side. With the measures taken by the British for the defense of Reykjavík there was also considerable dissatisfaction. Garrison camps had been placed within the town limits. Storage and broadcast-

[511]

ing facilities had been requisitioned. Restrictions on the civilian populace were too severe, the authorities thought, and plans for evacuation in case of attack were inadequate. What the Icelandic Government wanted in particular was a declaration that Reykjavik was an open, undefended city and the preparation, by the occupying forces, of local security measures for the protection of power plants and canneries. In those, and in such matters as the court procedure in cases involving civilians and members of the United States forces, the employment of Icelandic labor, American financial assistance for road, bridge, and public utilities maintenance, and even the strength of the American force-in all these, a clearer and formal definition of policy was desired by the Icelandic Government.37 The War and Navy Departments, on the other hand, were opposed to a general agreement along these lines. The only questions which, in the view of the War Department, could properly be the subject of a definite agreement between the two nations were the jurisdiction of American courts-martial and certain concomitant matters. The strength and composition of the American forces in Iceland were a matter for the War Department alone to decide; and all the other points brought up by the Icelandic Government fell in the field within which, according to the War Department, the commanding officer should have discretionary power. 38 Interdepartmental discussion continued through the fall of 1941. Meanwhile, the Second Echelon arrived in Iceland. With no formal understanding between the two governments, General Bonesteel thus not only had to organize, in collaboration with the American legation and the local authorities, the machinery through which co-operative action could be taken, but he also had to make palatable to the Icelandic authorities the unilateral decisions of policy, which, in a broad area, were his own. In the bases acquired in British possessions, the position of the American garrison was carefully and specifically defined by the agreement of 27 March 1941. No such agreement was signed with the Icelandic Government.

For more than a year the British military authorities had been coping with the problems that now faced General Bonesteel, and they had worked out fairly satisfactory procedures through which some of the more important problems were being handled. A joint Anglo-Icelandic committee had been

[512]

organized to adjudicate and settle claims against the British forces; a similar committee handled all questions concerning the employment of Icelandic labor, and a "Hirings Office" arranged all leases and contracts for the use of property by the military. This machinery, already functioning, was available to the American forces, and as early as 18 July, soon after the arrival of the marines, both the British and American consuls had urged that the United States become a party to the existing arrangements.39

After the Second Echelon arrived the Icelandic Government lost no time in bringing up the question of settling claims. During a conference with General Bonesteel on 23 September, at which Generals Marston and Homer and Consul Kuniholm were present, Prime Minister Jonasson spoke of it as one of the most important problems, and, to be sure, it was. He assumed that the American forces, following the British procedure, would set up a joint committee, which, he suggested, might consist of one member from the American military staff, one appointed by the Icelandic Government, and a justice of the Icelandic Supreme Court as arbitrator. A committee of this size, the Prime Minister believed, would be less cumbersome, and no less impartial, than the British joint committee made up of three Icelanders and two British members.40 Pertinent Army Regulations (AR 35-7020) provided only for the appointment of a board of one or more officers to settle claims, but the liaison plan of early June, which had been incorporated into the GHQ Operations Plan, authorized the force liaison officer to make arrangements for this purpose with the Icelandic Government, and thus opened the way for the use of a joint committee. The plan adopted by the American military authorities on 28 September combined the two procedures. A Primary Board, consisting of one officer who would attempt to reach an agreement with the claimant and settle the amount of compensation, was established in accordance with Army Regulations; and if the claim were unjustifiable or agreement impossible, the matter would then go to the joint Claims Board, a committee of three, such as the Prime Minister had recommended.41 On 20 October the name of the American appointee to the board was submitted to the Icelandic Government by the American Legation; on 20 November the two Icelandic members were named, and on 12 December the board held its first meeting. Of the eight claims presented, all

[513]

of them arising out of traffic accidents, two were disallowed and two deferred for future consideration. The four payments that were approved were scaled down from about $235 claimed to a total of some $105 allowed.42 For the payment of small claims such as these and pending the establishment of definite procedures, General Bonesteel had been provided with special funds, which eliminated the necessity of withholding the final payment until remittances came from Washington.

The question was immediately raised by the Icelandic member whether the decisions of the board were to be considered as final or merely as recommendations to the commanding general. If the reply had been sent in the form of an official note from the Legation, as had been the first intention, the query might well have become an issue. But General Bonesteel and Mr. Lincoln MacVeagh, the American Minister, agreed that it would be preferable for the American member of the board to point out, by informal discussion with the Icelandic members, that the commanding general was required by United States law to approve all expenditures of public money allotted to his command and for this reason alone he would have to approve all claims allowed by the board.43 The Joint Claims Board was, moreover, precluded by existing United States law from entertaining claims against individual members of the American forces for actions outside their official capacity, and it was inevitable that claims of this nature would arise. By the time this question was raised, however, the law had fortunately been changed.44

The joint board or committee, employed first in settling claims, was an obvious device for handling the questions that later arose in connection with the acquisition of property and the employment of Icelandic labor. These involved contractual relations and were, like claims, justiciable in nature. On the other hand, the problems incident to normal intercourse between troops and townspeople were totally different in character. Any deficiency in the conduct of civilians and soldiers toward each other was a matter for the respective authorities, not for a joint board. As a breach of discipline on the part of the soldiers was a responsibility of the military alone, so a breach of

[514]

the peace on the part of the populace was solely a matter for the civil authorities.

One of the key men among the local authorities was the chief of police of Reykjavík, Mr. Kofoed-Hansen, whose friendship with Consul Kuniholm simplified the handling of these problems. The situation was further eased by recognizing the right of civilian police to arrest members of the American force; while at the same time the chief of police made an especial effort to convince the American authorities that the mistrust in which he had been held by the British was unfounded.45 From the very start, fair winds favored the negotiations with Mr. Kofoed-Hansen. His first discussion with General Bonesteel on 6 October was, according to Minister MacVeagh, "an outstanding success." On this occasion, Mr. MacVeagh reported, General Bonesteel assured the chief of police that as few men as possible would be quartered within the city limits, that men on pass would be required to return to camp by 11:30 p.m., and that they would be forbidden to carry arms. Trouble spots would be declared out-of-bounds. General Bonesteel made it clear that his responsibility extended only to the conduct of his troops and that he would not impose unreasonable restrictions on the troops for the purpose of relieving the civilian police of part of their responsibility for maintaining public order. When, for example, the chief of police suggested that members of the garrison be forbidden to use taxicabs, since bickering and brawls between the troops and local cab drivers were a frequent complaint, General Bonesteel refused. Instead, a military bus service into Reykjavík was inaugurated, and regulations designed to prevent the men from defrauding cab drivers were issued. In this same general fashion, by personal, informal negotiation and the normal processes of military discipline, each problem that subsequently came up was handled. It was a method of approach that called for the utmost diplomacy on the part of the commanding general. But his ability in this difficult art was vouched for by the American Minister, who reported after the conference of 6 October with Mr. Kofoed-Hansen: "The General's comprehension of the importance of even the most minor issues in this whole matter of the relations of our forces and the Icelanders would seem to be equalled only by his tact and promptness in dealing with each one, while standing firm at all times for the dignity of his command and the respect due to the American soldier." 46

The successful relations between the military and Icelandic authorities

[515]

rested partly on General Bonesteel's practice of dealing through the appropriate nonmilitary agencies in all matters that were not primarily an Army responsibility. Thus when a question arose in October concerning measures for civilian relief in the event of an air raid, for which only the most elementary planning and a few half-hearted steps had been undertaken by the local authorities, the assistance of the Army was offered through the Legation and made available through the American Red Cross. Between the headquarters of the Iceland Base Command and the American Legation in particular there was the closest co-operation. In fact Mr. MacVeagh claimed that he was kept better informed by General Bonesteel and the American naval commander than by his own department.47 The same close relations prevailed between the military command and the consulate. Mr. Kuniholm, the consul, was himself a West Point graduate and both General Bonesteel and his chief of staff, General Homer, had been his tactical officers at the Academy. In Newfoundland and Trinidad, the lack of co-operation between Army headquarters and representatives of the State Department had, on the other hand, immeasurably added to the problems of the base commanders. Iceland demonstrated what teamwork could accomplish.

Much the same situation prevailed in American relations with General Curtis and the British force. The difficulties anticipated from a joint occupation did not prove to be entirely illusory, but those that materialized were, for the most part, matters of more concern to Washington and London than to Camps Pershing and Alabaster, the respective headquarters in Iceland. Differences of opinion between the War Plans Division and SPOBS over censorship in Iceland and between GHQ and the War Plans Division over the command of the joint garrison, and Congressional needling on this sensitive subject, failed to shake the friendly co-operation maintained by the two commanding generals in Iceland.48 On 19 April 1942, shortly before General Curtis returned to England, General Bonesteel had the pleasure of present-

[516]

ing him with the American Distinguished Service Medal. General Curtis thus has the distinction of being the first British officer to receive this award during World War II.

On the subject of his command relationship, General Bonesteel's instructions were vague: as long as the United States remained out of war he was to "coordinate" operations by "mutual cooperation" with the British. What his instructions left indefinite was spelled out, however, in the plan of joint operations agreed upon by the two commanders. Not only did the plan define the tactical responsibilities of the Iceland Base Command, but it provided, as well, for the joint use of certain facilities and services and for the free interchange of information between the two forces. The details of these and of any other topic of immediate, current interest to both commands were discussed at a formal interservice conference each month, as well as at the more frequent informal meetings of the two commanders. In this fashion a common course was decided upon in matters of policy.49

One of the more perplexing questions arose from the material aid given by the British to the arriving Americans. Under the arrangements made during the summer between SPOBS and the War Office, Nissen huts for American use were sent from England, erected by British labor, and provided with utilities under British contracts; British Army trucks had assisted in discharging the American convoys; and supplies, weapons, and equipment of one sort or another were from time to time turned over to the Iceland Base Command. No attempt was made by the British to place a value on the goods and services received by the Americans and nothing more than an informal receipt was required for the goods that were turned over. By mid-October the American staff officers most directly concerned had become disturbed about the informality of the procedure.50 Repeated requests that GHQ advise whether the procedure was satisfactory brought a reply, on 9 December, that the question was being considered by the War Department and in the meantime all supplies taken over from the British should be inventoried, assessed as to value, and receipted for, in. conformity with the GHQ Operations Plan. If the British would not assess the value of the goods, continued GHQ, the Americans must do it alone.51 Quite unknowingly, the Iceland Base

[517]

ARMY POSTS IN ICELAND. Nissen huts on "Main Street" of an Iceland camp (top). View of the mountains from Camp Pershing (bottom).

[518]

Command had been caught in the eddy of "Reverse Lend-Lease." The idea of reciprocal aid, which had been germinating since early summer, was intended to cover just such a situation as Iceland offered. And in Iceland the British Government made clear the position which it consistently took: that lend-lease and reciprocal aid transactions could not be balanced in terms of dollars and pounds. Discussions with British representatives in Washington during December failed to resolve the issue. On 31 December, GHQ notified the Iceland Base Command that all goods and facilities received from the British in Iceland would be included in lend-lease accounts and that, contrary to previous instructions, all inventories must bear a British assessment of value.52 The British force in Iceland continued to follow the policy fixed by its own government, but with lend-lease machinery now coming into operation the valuation question no longer rested in the hands of the Iceland Base Command.

Of all the administrative problems that had been anticipated, none had foretokened greater difficulty than the questions of housing and shipping. As it turned out, housing, although troublesome, proved to be less formidable than had been expected; and as to shipping, the problem became one of harbor congestion and of allocation between Icelanders, British, and Americans rather than an actual dearth of vessels. Both housing and shipping were closely tied to the continuing question of what reinforcements should be sent and to what extent the relief of the British should be carried. Troop movements to Iceland, whether reinforcements or relief, obviously depended upon accommodations for the men and berthing space for the ships. Yet troop movements were also a matter of strategy and policy. Should a reinforcement be decided upon in Washington, the problems of housing and port congestion could suddenly assume greater proportion.

When the Second Echelon moved ashore on 25 September there were enough Nissen huts available to house the entire American force, thanks to a Herculean effort on the part of the marines. They had not received word of the construction task expected of them until 19 August, but by dint of a 17-hour, 2-shift working day and by specialization of labor-one crew working on foundations, one on decking, another on tinning, and so on-the marines met the deadline. It had been touch and go, however. The last of the First Echelon had moved into their accommodations only a week or so before the Second Echelon arrived, and there were still lacking about 120 of

[519]

the total number of huts that Colonel Iry, the base engineer, had estimated would be required. After the Second Echelon had been crowded into all available quarters, Iry revised his estimates upward. Including those already in use, about 1,830 huts would, he reported, be needed to house the force adequately and to allow for contingencies. Although the Second Echelon had brought material for 200 huts along with them, an additional 280 would have to be obtained either from England or the United States to meet these requirements.53 Storage space was more urgently needed, but the requirements were not so readily calculated. The background of high confusion presented in the reports of the base engineer obscured what should have been clearly set forth, namely, the amount of space in use and the number of buildings on order at any one time, and the number and type of buildings needed to fill the estimated requirements. Perhaps the most that can be ventured as an observation is that one-fourth, or thereabouts, of the 200,000, or 230,000 square feet of storage space required was available when the Second Echelon completed discharge. A somewhat smaller amount was obtained by lease either then or shortly afterwards.54

The Question of Reinforcements and Relief

The question of sending additional troops to Iceland had come up even before the Second Echelon was fully established on shore. In a conference with the President on 22 September on the subject of reducing the strength of the ground forces, General Marshall adverted to the plan for relieving the British with the remainder of the 5th Division in the spring of 1942. To this the President gave his characteristic "O.K." ; but he also expressed the desire to have small groups sent to Iceland during the winter for the purpose of relieving corresponding British units and of permitting the return to the United States of any "misfits" among the American garrison. Marshall thought none too well of the idea, nor did General Bonesteel, to whom the Chief of Staff immediately wrote. General Marshall pointed out to the President the difficulty imposed by the territorial restrictions on the use of selectees; but he would, he assured Mr. Roosevelt, inquire into the Navy's ability to provide transports and escorts, and if it were possible to send troops dur-

[520]

ing the winter, it would be done.55 Two weeks later the subject was explored at a meeting in the office of the Deputy Chiefs of Staff. Besides General Bryden and General Moore, Deputy Chiefs of Staff, there were present Generals Malony and Gerow, and representatives of the Navy Department, of the Chief of Engineers, and of G-1 and G-3. The problem of culling selectees out of the 5th Division was discussed and questions of housing, shipping, and port congestion were raised. The suggestion was made by General Gerow that perhaps the marines could be brought home and their accommodations used for housing the Army troops. As to the number of men to be sent, it was General Moore's opinion that 8,000 was the most they should try to send before April, but on this matter the recommendations of General Bonesteel, of the Navy Department, and of the British would have to be considered.56 In WPD and GHQ the planning machinery now began to revolve in this new direction, toward a winter schedule of relief.

Since the interests of the Army, the Navy, the Maritime Commission, and the British were affected, Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, head of the Navy War Plans Division, proposed a conference of all interested parties for the purpose of drawing up the plan of relief. As a preliminary step, he suggested that an agreement be reached by the War and Navy Departments on certain basic issues, foremost of which, from Admiral Turner's point of view, was the question whether the marines would be withdrawn before the relief of the British was undertaken.57 Two of the other points raised by Admiral Turner-the question of providing air units "for general strategic purposes" in Iceland, and whether the United States would take over all British naval bases and services there-became increasingly important in later weeks, but the big stumbling block was the relief of the marine brigade. In spite of General Gerow's suggestions at the staff conference of 8 October, the Navy's proposal to withdraw the marines was coolly received by the War Plans Division. It was argued that relieving the marines would not further the President's purpose to release British units and that a general conference such as Admiral Turner had in mind would merely lead to a long delay. As for taking over British air and naval installations, it was the understanding of the War Plans Division that the relief of British ground forces only was

[521]

contemplated. In the suggestion for a general conference Army planners saw an undesirable departure from the tried procedure by which the INDIGO plans had been formulated. The winter relief schedule could best be arranged, the War Plans Division believed, by the usual method of joint action, and this was offered as a countersuggestion to Admiral Turner on 13 October.58 The questions raised by Admiral Turner could be used as the starting point for the immediate preparation of a joint directive, the War Plans Division suggested. But, until some agreement on withdrawing the marines could be reached, little progress could be made in preparing the new directive. Admiral Stark laid the problem before the President at a White House conference on 16 October, only to have it handed back as a matter that he and General Marshall would have to decide themselves. Finally, toward the end of the month GHQ was told to proceed with its plans without waiting for the joint directive.59

Meanwhile, General Bonesteel had no intimation that a change of plan was brewing until Marshall's letter of 23 September arrived on 7 October. At the time it was written no definite decision had been made, but a radio message from GHQ which had been received a day or two after the Chief of Staff's letter should have made it clear that the situation had crystallized in the meantime. The message instructed General Bonesteel to report immediately the order of priority in which he wanted troops sent during the winter. And he was asked whether a corresponding withdrawal of British troops could be arranged in order to make housing available. The size of the units and their sailing dates would be given to him later, the message concluded.60

General Bonesteel's opinion was, however, that troop movements during the winter would either force the occupation of the northern and eastern outports, which in that season was highly inadvisable, or else require a concentration of American combat troops in closer proximity to Reykjavík, which was undesirable. Housing and storage were, he believed, so uncertain that either the British would have to move out first and make their accommodations available to the incoming Americans, . or butting would have to be sent and erected before the troops arrived. The one would "hinge on the coordination of British shipping in order to make the relief synchronous," he wroth General Marshall, and the other would mean the shipment of hut

[522]

materials from the United States, since "the plan for hutting to come from England was not worked out." But it was most important, he thought, that nothing be done which would add to the shipping congestion at Reykjavík. Even the present schedule, he asserted, was too much for the port to handle, and consequently he and General Curtis were both going to recommend that supply levels be reduced, that priorities on shipping be set up, and that the arrival of vessels be staggered. These were the considerations which he thought should decide whether or not troops were to be sent to Iceland during the winter.61 And to make his position clear he strongly recommended, in his reply to GHQ's message, that until the British withdrew and the necessary facilities became available, no troops be sent to Iceland except the reinforcements he had already requested.62

The only reinforcements that General Bonesteel had requested at the time the matter of winter movements came actively under consideration were some six hundred men: service troops, military police, and additions for the aircraft warning detachment. He had asked on 5 October that these troops be sent in November, when there would be sufficient housing to care for them without dependence on British withdrawals. Then, after receiving General Marshall's letter and GHQ's radiogram, General Bonesteel gave GHQ a list of Quartermaster, Engineer, and Signal Corps units, totaling about 1,500 men, that he wanted sent to Iceland when housing became available. His own immediate needs governed General Bonesteel's requests, but it seemed to GHQ that they could be fitted into a scheme for relieving British units. Accordingly, on 16 October, GHQ informed General Bonesteel that the troops he had requested on the fifth of the month would be sent about 1 December (shipping was the cause of the delay), and that further movements would await word from Iceland that the necessary facilities were available. At the same time General Bonesteel was authorized by GHQ to work out a complete plan of relief with General Curds on the basis of relieving the British as rapidly as port facilities and housing permitted.63

Meanwhile, the Special Observer Group had been keeping in touch with the War Office in London concerning the withdrawal of British units. The War Office, SPOBS reported to the War Department, was agreed on the

[523]

practicability of relieving certain units in the Reykjavík area during the winter; but it was unwilling, because of the special winter training program in Iceland, to withdraw more than one infantry brigade before 1 February 1942. The British nevertheless desired assurances from the War Department that the relief of the whole division would be completed by the end of April. Being of the opinion that the defense of the Reykjavík area did not require all ten infantry battalions then stationed there, the War Office had no objection to withdrawing two British battalions before the American troops arrived, which, continued SPOBS, would take care of the housing questions.64

Using the report from SPOBS as his starting point, Major Lemnitzer of GHQ had worked out a tentative plan of relief which involved the withdrawal of two British battalions before 1 December and another two battalions of British infantry, or the equivalent number of service troops and artillery, before 1 January 1942. As for the incoming movements, the 600 service troops and military police scheduled to sail from the United States about 1 December would be followed on 10 December by about 1,200 Quartermaster and Engineer troops; and the rest of the units on General Bonesteel's priority lists would sail about 10 January. When General Bonesteel apparently took the proposed withdrawal of British infantry to mean either that American combat troops would be substituted for the service troops he had requested or, if not, that the defenses of Reykjavík would be seriously weakened, a misunderstanding arose that resulted in a rather heated exchange of radiograms between the general and GHQ.65 The atmosphere was not long in clearing, however. It was made plain to General Bonesteel that his wishes as to troops and arrival dates would be followed, and that there was no objection to the British withdrawing noncombat troops provided the relief proceeded as rapidly as troops could be accommodated in Iceland.66

On 7 November General Bonesteel reported to GHQ that two British infantry battalions plus service troops would leave during the first part of December, and that another battalion plus service troops would depart early in the next month. As a complement to this change, the 2d Battalion, 10th

[524]

U.S. ARMY TROOPS ARRIVING IN REYKJAVIK, JANUARY 1942

Infantry, was added, at the request of General Bonesteel, to the movement of American troops planned for January; and the 50th Signal Battalion was added to the December movement. At this point the arrangements in Iceland were, Bonesteel reported, going ahead very satisfactorily.67

Meanwhile, during November some 1,100 British troops had been returned from Iceland. Another 3,400 men were to be withdrawn during the last two weeks of December, which would bring to a little more than 6,300 the number of British troops relieved since the arrival of the Second Echelon in September.

The consensus had been that any movement of troops, either of reinforcements or for relief of the British, would depend upon housing and the ability of the port to handle the movement. Yet if the arrangements for relieving the British garrison had awaited solution of the housing and port problems, progress would have indeed been slow.

[525]

Housing requirements, not to mention the confused storage situation or the undetermined Air Force needs, would not have been met by the construction program. The base engineer estimated at the end of November that the additional huts needed to fill the present requirements and those of the planned additions to the force would number 765, which were to be erected out of materials either on hand or previously ordered. Actually, during the next two months only 268 huts were built, and the remainder of the 829 huts that became available during the period were those that were turned over to the Americans by the departing British troops.68 It was fortunate that no hitch appeared in the British convoy schedule.

The port construction program, designed to speed up cargo operations, had been laid down before the decision was made to undertake troop movements during the winter. The improvements along Reykjavík waterfront would, it was estimated, increase the available pier space by about 37 percent; but the earliest completion date that could be expected was 1 March 1942. A major cause of the congestion in the port was the shortage of labor; but, in this too, no improvement could be looked for until the arrival of additional port troops in January. The question, then, was what could be done with the resources available. During November about 31,000 measurement tons of cargo for the American forces were handled through the port of Reykjavík. How could this performance be bettered in order to take care of the 22,400 tons that the troops scheduled for movement in December would bring with them? 69 Considerable thought, much discussion, and reams of paper were devoted to the problem. Several interdepartmental conferences were held in Washington to discuss the co-ordinated use of transport shipping, but no agreement could be reached as to whether the Navy, the War Department, or the Maritime Commission should be given control. Partly in recognition of the need in Iceland for closer co-operation on shipping matters, the Navy, on 8 November, announced that a naval operating base was to be established at Hvalfjördhur.70 But the most effectual measure perhaps was the reduction in the level of maintenance supplies from 180 to 120

[526]

days, which had been recommended by the joint Port Committee in Iceland, approved by General Bonesteel, and which was, on 10 November, officially established by the War Department. It was to be accomplished by suspending maintenance shipments for two months, and this, according to Lt. Col. Ernest N. Harmon, of GHQ's G-4 Section, would mean a saving of 30,000 tons in each of the two months. Colonel Harmon, it should be added, viewed the saving more as an opportunity to send additional construction equipment and special supplies to Iceland than as a means of reducing the port congestion there. Nevertheless, if cargo estimates for the December and January troop movements and the tonnage figures for November were at all accurate, the congestion must have been substantially reduced; for only 28,000 or 30,000 tons of cargo were shipped to Reykjavik in December and January. The reduction was achieved, however, only at the expense of shifting the jam from Reykjavík to New York, where 45,000 tons of cargo for Iceland had accumulated by 8 February1942.71

The program for relieving the British during the winter was only one of several new developments. The changes made in the mission assigned to the American forces were far more pregnant than the adoption of a new schedule of relief; but, interestingly enough, they had, for all their significance, less immediate effect on the situation in Iceland.

The INDIGO-3 directive, in setting forth the joint Army and Navy tasks, had specifically interpreted the approach of Axis forces within fifty miles of Iceland to be "conclusive evidence of hostile intent" which would "justify" attack by the defending United States forces. By the end of August 1941, the President was willing to bring deeds and diction more into line. In approving the directive on 28 August he expressed himself as follows: ". . . I think it should be made clear that the joint Task . . . requires attack on Axis planes approaching or flying over Iceland for reconnaissance purposes." 72 Here then was a "shoot on sight" order six days before the Greer incident took place on

[527]

4 September; but, for almost eight weeks past, the American forces in Iceland had been attempting to do by justification what the President now wanted done by injunction. The new phraseology brought no added responsibilities nor any changes in the conduct of operations.

More meaningful were the directions the President gave to Admiral Stark on 6 September to have identical tasks assigned to the Navy and to the Army Air Forces in Greenland and Iceland. As a result, the Army was given the enlarged responsibility of supporting naval operations in the waters between Iceland and America and of destroying any Axis forces met within the Western Atlantic Area. Although dispatched from GHQ on 23 September, the formal notification of this change was apparently lost en route or mislaid on arrival. For almost two months the Iceland Base Command continued to be unaware that the President's memorandum of 6 September gave the Army a new role. And of the Iceland Base Command's unawareness the War Department had no inkling until mid-November.73 In any event, the role could not be played without the necessary properties. The only Army planes in Iceland were the fighter planes of the 33d Pursuit Squadron; the brunt of high-seas patrolling done by the Americans had been carried by the PBY's of the naval air force. Now the War Department, to consist with its new air mission and to make possible its assistance in the Battle of the Atlantic, proposed to send heavy bomber reinforcements to Iceland. They were to be, so Secretary Stimson informed the President on 21 October, the advance unit of a team of four-engine bombers, the reserve component of which had already been sent to Newfoundland. "In other words," he declared, "we contemplate the possibility of sweeping operations by these long-range bombing planes and have planned to place them in separated bases to facilitate that purpose as well as to protect against air attack on either base." 74

But the War Department had not reckoned either with the overcrowded and unsatisfactory state of Reykjavik airfield or with the misapprehension that ground support and interception were still the sole mission of the Iceland Base Command air force. An inquiry from GHQ as to whether housing was available and runways suitable for medium and heavy bombers brought forth the reply that light bombers were what was needed, and that the Navy proposed sending a land-based bomber squadron in December, which would com-

[528]

pletely fill the accommodations at Reykjavik airfield. A second message to General Bonesteel, on 14 November, informed him that "in order to increase your defense capabilities and to further army air mission of supporting the fleet" the immediate dispatch of an Army bomber squadron, either medium or heavy, was desirable. "Either type . . . ," it was stated, "will permit attack well out to sea as well as defense against land operations .... Light bombers are of limited use." 75 Only at this point, apparently, was it recognized that the Iceland Base Command air force had not, until now, known that "attack well out to sea" was one of its tasks. In his reply to GHQ on 16 November, General Bonesteel explained his position: "Your radio of 14 November . . . gives Army Air Force new mission of supporting the fleet, which is the object of the squadron the Navy states will arrive in early December." 76 Since Reykjavik airfield could not accommodate two additional squadrons and since the Navy was already putting up housing at the nearby seaplane base, he recommended that the Navy bombers be given priority.