CHAPTER XX

The North Atlantic Bases

in Wartime

As outposts of defense, the North Atlantic bases were only imperceptibly affected by the entry of the United States into the war. More than two months before, instructions had gone out to the American garrisons to dispute actively the approach of any Axis military plane or naval vessel. Iceland had gone on the alert even earlier. The ultimate decision that would bring into action the guns of the American garrisons had thus rested with Hitler and on his view of what was expedient. It had not depended on America's status, whether of belligerency, nonbelligerency, or neutrality. In recognition of these circumstances, reinforcements had been dispatched to the Atlantic outposts throughout most of 1941. This is not to say that the bases in the Atlantic escaped, even for a time, the hard impact of war. The affirmation in the ARCADIA Conference (the Anglo-American conference in Washington, December 1941-January 1942) of the strategy of concentrating an American air force in the United Kingdom acted as a catalyst on the hitherto uncertain and somewhat nebulous proposals that the United States take over the North Atlantic air route-the shortest path between America and the European front. As way stations on this route both Greenland and Iceland now acquired a new importance, in which Newfoundland, as one of the terminal points, shared.

But the first blow had come from the far side of the world, and the demands of strategy had to be adjusted to the danger of the moment. Air reinforcements destined for the North Atlantic were hastily rerouted toward the Pacific. The B-17's of the 49th Bomber Squadron, on the eve of their departure for Newfoundland, were diverted across country to California in spite of the fact that the squadron's ground echelon was already in Newfoundland. The bombers intended for Iceland likewise reached a destination far from that originally planned, and for a few days there was a strong possibility that the scheduled troop movements would go the way of the planes.

[532]

Of the four outposts in the North Atlantic, Iceland alone presented a major, immediate problem. The reinforcement of Newfoundland and Bermuda would require the transportation of comparatively small numbers and the distances were not great. Greenland would be frozen in until spring. Furthermore, early plans and prior commitments and the desire of the British to transfer their garrison gave Iceland a special position in the tug of European strategy versus Pacific needs.

As matters stood, the United Stares had a little more than 10,000 men, including the marines, in Iceland on 7 December 1941. The two troop movements planned for December had been combined into one of about 2,100 men, which was ready to leave on 10 December, and preparations for sending approximately the same number of troops on 20 January were well under way. Tentative plans for the next four months, which would include relieving the marines, were being worked out. Now, suddenly, all these plans and preparations were thrown into jeopardy. Three or four days of uncertainty passed and then, on 11 December, the War Plans Division notified GHQ to carry out the December move according to plan. Four days later, on 15 December, the troops sailed. But the final decision on all subsequent movements was postponed.1

Twice during these weeks in December 1941 Secretary Stimson urged the President to reconsider the Iceland situation and withdraw the American garrison. The British, he argued, could do the job without the problem of leave and rotation, with all its psychological ramifications, that confronted American troops.2 In Mr. Stimson's view, a British garrison would in no way hinder the United States from making use of Iceland as an air or naval base. But the Navy thought otherwise. The President, whose interest had been aroused in the first place by Iceland's naval importance, agreed with Mr. Stimson that the situation ought to be restudied; but his reaction to the Pearl Harbor attack and to the removal of the last remaining restrictions on the use of selectees was that now the garrison ought to be strengthened. He

[533]

would be "much happier," he wrote to Secretary Stimson, "if we had another 10,000 men in Iceland." 3

The ARCADIA conferees acted promptly in accordance with the wishes of the President and Prime Minister and decided to carry through the relief of the British in Iceland, but the matter of a timetable and priority in relation to the other major operations proposed for the Atlantic theater was not so easily settled. In deference to the wishes of Admiral Stark and the Navy planners it was agreed to relieve the marines first, and on this account the troop movement scheduled for January was greatly expanded -6,000 and 8,000 men were the two figures discussed. But before the conference ended, shipping requirements for the Pacific made it necessary to abandon the idea of relieving the marines for the time being and to restore the original schedule of moving about 2,500 men to Iceland in January. 4

As it turned out, the relief of the marines and the relief of the British garrison were carried out simultaneously, over a period of six months. After the arrival of the December troop convoy a battalion of marines had taken over the positions of one of the British infantry battalions, which was immediately returned to the United Kingdom. Then the 2d Battalion, 10th Infantry, which arrived in the January convoy, took over from the marine battalion and it returned to the United States. No troops arrived in February. In March a small British force and the last remaining units of the marine brigade departed upon the arrival of the 2d Infantry (minus one battalion) and accompanying units. A large American convoy arrived in mid-April and another in May with a total of about 8,700 troops, and this enabled most of the remaining British troops to be withdrawn. After 11 May only the British 146 Infantry Brigade, distributed among the three outports of Akureyri, Seydhisfjördhur, and Búdhareyri, and some Royal Air Force units remained. The better part of the job the United States had undertaken twelve months before was accomplished. There were now, at the beginning of June 1942, about 24,000 American troops in Iceland; but in the meantime Iceland's defense requirements had risen. The building of the Keflavík airfields, air ferrying activity, and troop transport operations over the sea lanes, and the fact that the United States had become one of the belligerents all meant that the size of the garrison had to be revised upward. Shortly after Iceland's inclusion in June in the new European Theater of Operations, large additions to the American forces arrived in July, August, October, and

[534]

December, so that by the end of 1942 the garrison in Iceland had grown to approximately 38,000 men stationed at nearly 300 camps and posts.5

Both Iceland and Greenland had been fitted into the strategy of the war within a month after the United States entered it. The unfinished air bases in Greenland, which the Air Forces had earlier sought to justify on grounds of their importance to the direct transport operations between Newfoundland and Scotland and to antisubmarine patrol and reconnaissance operations, and the projected fields at Keflavík, which GHQ and the Iceland Base Command had originally envisioned as tactical fields, were now recognized for what they could become, namely, essential to the American build-up in Britain. But before their usefulness could be realized much construction work remained to be done and adjustments had to be made to several shifts in plans.

By late spring of 1942, when open water began to appear in the Greenland fjords and construction activity could be resumed at the BLUIE bases, there had been adopted the BOLERO-SLEDGEHAMMER-ROUNDUP strategy which called for a major effort from the British isles and the movement overseas of the Eighth Air Force. In furtherance of this undertaking the North Atlantic staging route was merged into the grandiose CRIMSON project, a sweeping design for airfields and weather stations along three different trans-Canadian routes that converged in the neighborhood of Frobisher Bay. By the time the first planes of the BOLERO movement were ready to take off, at the end of June, the CRIMSON project had been sharply curtailed, lest the child swallow the parent, and by August the planning for an African landing had taken precedence over BOLERO, that is, over the preparations for a cross-Channel operation. These and later shifts in strategic planning were reflected in various adjustments and readjustments in construction plans and base development, especially in Greenland; but the changes in base plans were chiefly of degree, not of direction.6

The growth and development of the Greenland bases went hand in hand with the first rush of ferrying operations. The first BOLERO flight landed at BLUIE WEST I on an unfinished runway ill-provided with taxiways and parking areas. Weather and communications facilities, aids to navigation,

[535]

and billets and messing facilities for the flight crews were wanting. Ferrying Command officers noted a shortage of well-trained and experienced air base personnel.7 To fill these gaps without halting or greatly impeding the ferrying operations was the aim, only partly achieved during 1942. A prolonged spell of bad weather in August and September seriously hampered construction activity at BLUIE WEST I. In September, the first of three disastrous fires completely destroyed the mess hall at Ivigtut. Meanwhile, German submarines had begun to take their toll of ships, men, supplies, and equipment. The sinking of the USAT Chatham on 27 August was the first American troopship loss of the war. Fortunately, almost all on board were saved; but it was a foretaste of more bitter experiences to come. Although new weather stations were opened and new airfields started, the route was far from being completed by mid-December, when ferrying operations ceased for the winter.8 During the six months it had been in use nearly nine hundred planes had taken the route.

During the same period the strength of the Greenland Base Command was doubled. To reinforce the garrison to any great extent during winter had been impossible, so that in April 1942 it was about the same size as it had been the previous December. Then, in May, defense forces were sent to Ivigtut and BLUIE WEST 8. This brought the strength up to 1,383 officers and enlisted men, where it stood on 30 June when the ferry traffic was beginning to come through. BLUIE WEST I still had the largest garrison, 731 men, compared to 238 at Ivigtut and 379 at BLUIE WEST 8, and the bulk of the garrison now consisted of antiaircraft and coast defense troops, and of Air Corps and service detachments, instead of engineers.9 Through the summer and fall reinforcements continued to reach Greenland. By the end of November, just before winter weather closed the route to ferrying operations, the strength had risen to approximately 2,856 men, more than half of them stationed at BLUIE WEST I.10

Most of the additional troops belonged to the infantry battalion that arrived in early November and was divided between BLUIE WEST I and

[536]

BLUIE WEST 8. The War Department had originally planned to send the 2d Battalion, 3d Infantry, to Greenland, and in preparation for the move the Headquarters and Headquarters Company were dispatched at the end of April. After the troop movements of May and June got under way, Colonel Giles, the commanding officer in Greenland, recommended that the defense of the airfields be placed in the hands of strong antiaircraft and tactical air units. Specifically, he requested one pursuit squadron, one composite pursuit and bomber squadron, three batteries of 90-mm. guns, and one battery of 155-mm. guns. Lt. Col. Robert W. C. Wimsatt, who relieved Colonel Giles when the latter assumed command of the North Atlantic Wing of the Air Forces Ferrying Command, concurred in the views of his predecessor, as did General Spaatz, who had stopped in Greenland on his way to take command of the Eighth Air Force in Britain. "As a basis for planning," the War Department was willing to, and in fact did, approve an even larger air and artillery augmentation; but for the immediate present it proposed to go ahead with the plans to send an infantry battalion.11 Meanwhile, in order to take care of the increasing demands made upon his headquarters, Colonel Wimsatt requested additional Quartermaster, Ordnance, and other overhead personnel, and at the same time requested that a Headquarters and Headquarters Company for the Greenland Base Command be activated with the headquarters personnel of the 2d Battalion, 3d Infantry. The War Department gave its approval, and on 18 July dispatched the appropriate directives to Army Ground Forces and the Services of Supply. Some months later, in October, Colonel Wimsatt's request for additional supply and service personnel was granted also. Meanwhile, on 1 September, after the Base Command Headquarters was activated, the Head quarters and Headquarters Company of the 2d Battalion, 3d Infantry, was inactivated and its personnel transferred to a newly constituted unit: the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 73d Infantry Battalion (Separate). On the same day the four companies of this battalion were activated at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and on 11 November 1942 they arrived in Greenland.12

During the next six months all the American outposts in the North Atlantic were built up toward peak strength, while at the same time plans

[537]

were being laid to reduce the garrisons. All except Greenland reached the peak before midsummer, 1943, and then started to dwindle. Before retrenchment set in, the Iceland garrison had risen to approximately 41,000, the Newfoundland garrison to about 10,000, and Bermuda to about 4,500. The Greenland garrison continued to grow for several months after the others began their decline and finally reached its peak strength toward the end of the year, when about 5,300 men were maintaining lonely vigilance there.13 Plans for using the Greenland airfields for antisubmarine operations, the sinking in February 1943 of the transport Dorchester with the loss of 605 men en route to Greenland, the resumption in 1943 of enemy activity on its northeast coast, and the development of plans for the invasion of Europe (for which Greenland weather reports would be of vital importance) all suggest themselves as explanations for the lag in reducing the size of the Greenland garrison.

The entry of the United States into the war not only gave new importance to the Greenland airfields, but likewise brought construction plans to full maturity in Iceland and made necessary a review or recasting of the program in Bermuda and Newfoundland. At all the bases the obvious reaction was to eliminate those items of construction that were not essential to the purposes of actual defense. In Newfoundland, such things as family quarters, theaters, and officers' and service clubs were either eliminated outright or replaced by temporary structures, and such facilities as additional gun batteries and reinforced concrete storage igloos were added instead. In Bermuda, where the ease of handling the local building stone and the availability of concrete block made permanent -or semipermanent-type construction less of a problem and more easily built, fewer temporary buildings were substituted. Nevertheless the program was revised. The runways, hangars, cantonment housing, barracks, and similar facilities were given urgent priority; certain less essential construction was placed on a deferred status.14 In Iceland, the need of an additional bomber field and the desirability of additional fighter plane facilities merged and became the Keflavík air base project.

The Army Air Forces, GHQ, and the Iceland Base Command had for some time been united in favor of an additional bomber field in Iceland. During November and December 1941 site and soil surveys, reports, and

[538]

recommendations had been made, every one of them favorable, but authority to proceed with the preliminary clearing and grading had not been forthcoming until 29 December. Two weeks later, on 14 January 1942, General Somervell's office recommended, with the concurrence of the Air Forces, that the Army Engineers at once begin construction of an airfield in the vicinity of Keflavík suitable for heavy bombers and that the necessary funds be provided therefor.15 In the meantime, while the pros and cons of a bomber field were being studied, Colonel Morris, commander of the Iceland Base Command's air forces, had been unobtrusively getting the construction of a new fighter field under way as part of the basic defense mission. As soon as the bomber field received official approval, the fighter field was fitted into the project as a satellite field. Thus, considerable progress had already been made by the time the first civilian construction gangs arrived in May. They were set to work on Patterson Field, as the satellite airfield was soon named, and when the first planes of the Eighth Air Force began coming through on their way to England, early in July, two of its three runways were in use.16 Construction work on the main airfield, Meeks Field, was started on 2 July and was taken over in August by one of the first Seabee units organized. A B-18 bomber carrying General Bonesteel and high ranking officers of his, staff, and their guests, made the first landing at Meeks Field on 24 March 1943, and with appropriate ceremony General Bonesteel declared the field officially opened.17 By the end of November 1943 the Greenland airfields had been completely graded and surfaced. All the links in the "Snowball" route to England had been filled in. "The major problems concerned with aircraft ferrying had been largely solved," states the official history of the Air Transport Command. "Ferrying had become virtually a routine operation." 18

One of the sharpest nettles growing out of the Pearl Harbor attack was that hardy perennial, the problem of unity of command. "Lots of paper," as General Marshall once observed, had been expended through the years on

[539]

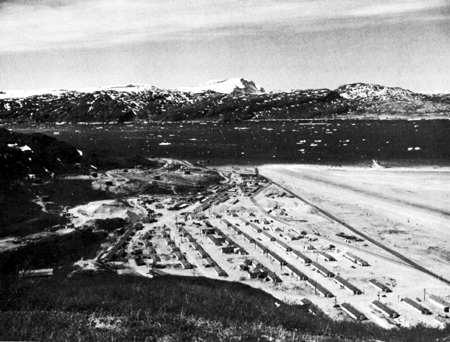

SECTION OF A GREENLAND AIRFIELD, 1943

this esoteric question of how command should be exercised when different services were involved and who should exercise it. The question verged on the philosophic, and the points at issue-unity of command versus mutual co-operation--were absolute terms, not susceptible to compromise. It was somewhat like the conflict between "positivism" and "relativism," which, to the total indifference of most laymen, provides among professional historians a perpetual source of argument and a convenient explanation for the shortcomings of their fellows. To Secretary Stimson and the professional military men, the resounding defeat On 7 December 1941 seemed attributable in part to this long-standing disagreement over the principles of joint command, and one of the reactions to the blow was an effort on the part of the War Department to recreate each of the various overseas bases into a unified command.

In spite of all the sound and fury, the argument boiled down to the issue of which higher headquarters would have responsibility for any given operation. The answer would obviously be determined by the nature of the

[540]

operation and the particular circumstances of the case. Since the answer generally was found in this way, and since in actual practice integrated operations did not necessarily come with unity of command, nor unity of command with integrated operations, it is fairly clear that the opposing advocates were not misled by their own arguments and really saw the issue for what it was.

To the extent that it involved the Atlantic bases, the fundamental issue was whether air units would be more appropriately employed in operations in support of the fleet and under Navy command, or whether they were primarily for local defense and should be under Army command. At Bermuda and Iceland the planes in dispute were Navy patrol bombers; at Newfoundland they were Army aircraft. The roots of the problem went back, in the case of Bermuda, to the agreement of April 1941 by which the Navy undertook to provide planes for local defense purposes, and, in the case of Iceland, to President Roosevelt's directive of 6 September 1941 in which he called fox the assignment of identical tasks to the Navy and the Army air forces there. There were complicating factors. In spite of, or perhaps in ignorance of, the April agreement regarding Bermuda, Captain James, naval commandant there, was convinced that the base should function primarily as an operating base for the fleet, not principally as a naval air station, and that his own proper place in the chain of command was under the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT), not the Commandant of the Fifth Naval District, as his original orders seemed to indicate.19 But if this should be the case, his planes would then be units of the fleet and not appropriate elements of a local joint command. This question was not decided until 3 February 1942, directly after the Army forces in Bermuda were placed at the disposal of the Navy commander.20 The presence of RCAF, RAF, and British Navy units at Newfoundland and Iceland, the wide disparity in strength between the Army garrison and the local naval defense forces in Iceland, and, finally, the inadvertence by which the Iceland Base Command was not apprised of the extension of the Army's mission until months afterward were additional complications.

The command pattern that took shape after the attack on Pearl Harbor had been molded by these complications. When the Navy Department on 4 January formally proposed that "unity of command" be established in Bermuda under CINCLANT, an arrangement similar to the one shortly before

[541]

placed in effect in Hawaii, GHQ and the War Plans Division of the General Staff found themselves on opposite sides of the question. In the exchanges that followed neither GHQ nor the War Plans Division referred to the April 1941 agreement. GHQ could see no reason for the Navy's proposal except as a means of securing the naval shore establishment more fully under the control of the fleet or of facilitating the conduct of relations with the local British authorities, and neither purpose, according to GHQ, required placing Army forces under Navy command. When the War Plans Division countered with the argument that the defense of Bermuda depended upon the Navy's control of the seas, that the operations of all the forces in Bermuda would be primarily directed toward maintaining that control, and that for this reason the Navy should have command, GHQ replied that Bermuda had been established as an outpost to defend the continental United States against attack, that the primary aim was to deny the islands to the enemy, and that the Army was the service principally charged with this mission.21 The view of the War Plans Division prevailed. On 30 January the Chief of Staff notified GHQ of his concurrence in the Navy's proposal, and GHQ grudgingly acquiesced. Four days later the intra-Navy disagreement of air station versus operating base was settled by Secretary Knox in favor of Captain James and the naval operating base. Meanwhile, the command problem had been partly laid to rest in Newfoundland also. In late October and early November 1941 Canadian naval forces on ocean escort duty, outside the coastal zone, were placed under the control of CINCLANT, and some measure of co-ordination in air patrols was worked out by the RCAF and the Commanding General, Newfoundland Base Command. It was reported, at a meeting of the Permanent Joint Board on Defense, United States-Canada, on 10 November, that orders were being issued placing the American air units under the command of CINCLANT for operations in protection of shipping on the high seas, but even for this limited purpose a completely unified command did not come into existence until after the United States was carried into the war.22 Not until January 1942 did the Canadian Government give its consent to a similar arrangement for the RCAF.

[542]

In spite of the fact that the United States had now entered the war, that the Army had recognized the Navy's "paramount interest" in the defense of Bermuda, and that Army air units in Newfoundland had been placed under Navy command for the performance of a particular task, there still remained a few ripples of disagreement. In Newfoundland part of the difficulty lay in the relationship between the American and Canadian forces there. The ABC -22 plan, which came into effect with the entrance of the United States into the war, provided for co-ordination of effort by mutual co-operation; but the United States in a protocol to the base lease agreement of March 1941 had expressly recognized the predominant interest and over-all responsibility of Canada in the defense of Newfoundland. The installing of American harbor defenses at St. John's, in addition to existing Canadian defenses, and the stationing of American air units at the Gander airfield, in addition to RCAF units, created areas of divided responsibility. A suggestion by the Canadian Army commander in Newfoundland that Canada assume responsibility for manning the American harbor defense battery received short shrift; and a complaint by the American air commander at the Gander airfield that closer co-ordination was necessary like wise was of no effect. Nevertheless, a joint defense plan prepared by the Newfoundland Base Command in November was accepted by all the commanders concerned, with the exception of the RCAF commander. In December, after the United States entered the war, a Local Joint Defense Committee, similar to those set up in the Caribbean, was formed for the purpose of reviewing and revising the existing defense plans. The wrangle over unity of command among the American services, the autonomous position of each of the Canadian services in Newfoundland, and difficult personal relations between the several commanders prevented the joint Defense Committee from making much progress. There continued to be pressure for giving the commanding general of the Newfoundland Base Command supreme command in Newfoundland. In February, General Drum, commanding general of the Eastern Theater of Operations, recommended that all forces in Newfoundland, Canadian as well as American, be placed under the command of an American officer, without any limitation. GHQ, which was the next higher authority above General Drum, had long favored the task force scheme of organization, an essential feature of which was the unification of forces under a single commander, and now GHQ urged that General Drum's recommendation be adopted. General Embick, senior Army member of the United States-Canadian defense board, was not, on the other hand, favor ably impressed. Considering how difficult it had been to obtain the assent

[543]

of the Canadian Government to the existing arrangement, General Embick was convinced that any effort to carry out General Drum's recommendation would fail and only impair what co-operation there already was. The War Plans Division agreed with General Embick and replied to General Drum accordingly.23 Shortly afterwards the Canadian Government established a unified command in Newfoundland with a joint operations center for all three Canadian services. Relations between the American and Canadian commanders began to improve, and in the course of the next six months or so, there was a marked growth of co-operation between the two forces. The American command joined the Canadian joint operations center; a joint United States-Canadian local defense plan was prepared and approved; and joint field exercises were held. By 1 October 1942, a satisfactory relationship between the two forces had been established, solely on the basis of the fine spirit of co-operation that existed between the two commanding generals.24

The command arrangements agreed upon for Bermuda had meanwhile come under the fire of GHQ. Instructions sent by CINCLANT to the Naval Operating Base, Bermuda, on 4 February, described the procedures somewhat as follows: the senior United States Navy officer afloat at Bermuda or the senior officer of the joint local defense forces eligible to command -whichever of the two might be senior- would assume command as the deputy of CINCLANT; the senior Navy officer afloat, if upon him the command devolved, was authorized to call upon local defense forces to support the fleet, as the situation required; and the senior officer of the joint local defense forces, if he were to assume command, was authorized to assign local defense tasks to units of the fleet as long as these tasks did not prevent the execution of fleet tasks.25 The arrangement was cumbersome, made so perhaps by the fact that there was still uncertainty whether the naval operating base was technically a fleet or a shore-based activity-and by the fact that Captain James was junior in rank to General Strong, commander of the Bermuda Base Command. The opinion of GHQ was that this procedure appeared "to utilize all local forces to best advantage in the support of the fleet, but does not provide a satisfactory basis for the assignment of responsibilities for the defense of Bermuda.26 General Marshall

[544]

had already signified to Admiral King his willingness to assign as commander of the Bermuda Base Command an officer junior to the commandant of the Naval Operating Base. But then the promotion of Captain James to Rear Admiral, on 18 February, made a change of officers unnecessary; and it placed responsibility for the defense of Bermuda squarely on the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As to the limited authority the local defense commander could exercise over units of the fleet, and of which GHQ had also complained, it was the view of the War Plans Division that "this is considered sound." 27

One outgrowth of the Bermuda command question was the extension of the same problem to Iceland. GHQ, in arguing against giving the Navy command authority over -the Bermuda forces, had pointed to Iceland as an example. The situation there, according to GHQ, was similar "in principle," and if it seemed "advisable to yield to the Navy" in the case of one then it might be equally advisable in the case of the other, GHQ inferred.28 In actual fact, if not in principle, the two cases were as far apart as the islands themselves. Up to this point the Navy had not raised the question of command in Iceland, and the Army War Plans Division would have preferred to let the issue sleep; but GHQ chose this moment to inform General Bonesteel that the joint Army-Navy defense plan which he and the local naval commander had drawn up the previous fall had been scuttled by the Navy Department.29 Rear Adm J. L. Kauffman, the commandant of the naval base at Iceland, immediately asked for instructions concerning his command relationships, and General Bonesteel shortly afterwards sought clarification from GHQ, which by this time was being gradually taken out of the picture by the impending reorganization of the War Department. Fresh impetus came from the White House. Mr. Lincoln MacVeagh, the American Minister to Iceland and a personal friend of the President, arrived in Washington at this juncture with a report in which he strongly urged a

[545]

unified command. There had been no real friction, he said, but a lack of liaison which had led to misunderstanding, delays, and in one case to the fatal shooting of a Navy enlisted man. Without concerning himself with the purely military matter of operations, Mr. MacVeagh argued that a unified command would centralize responsibility for unloading cargo and moving troops and supplies, would improve the security service, and would steer into a single channel all questions having to do with the local government. More pertinently, he suggested that for reasons of rank, administrative experience, and convenience (the Army had a larger staff in Iceland the over-all command be given to the commanding general of the Iceland Base Command rather than to the naval commander.30 Sent over to Secretary Stimson by Mr. Harry Hopkins, Mr. MacVeagh's report received the enthusiastic endorsement of the War Plans Division, which now had no hesitation about bringing the question into the open. Admiral Stark was asked for his views. He, in the meantime, had ordered Admiral Kauffman to submit a report on the situation; and the latter agreed that the lines of command in Iceland were exceedingly complicated. But the remedy, as Admiral Kauffman saw it, was greater control by the U.S. Navy.31

Thus the issue, touched off by the Bermuda question and by Washington's rejection of the Iceland defense plan, was transferred to the efforts of General Bonesteel and Admiral Kauffman to agree on a revised version of the plan. The particular point on which the controversy now focused was the tactical control of the Navy patrol planes in Iceland, of which there were ten or twelve. After long negotiation the most the two commanders could agree upon was that in the event of an enemy assault the Navy planes would be employed "in conjunction with the shore defense systems," under the principle of mutual co-operation, when it was "clearly evident" to the commandant of the naval base that the aircraft would not be needed for fleet tasks.32 Although General Bonesteel considered this provision an unsatisfactory solution he agreed to it in order to save the rest of the plan. The Operations Division, successor to the "tear Plans Division, advocated the same course that its predecessor had recommended: that the existing command arrangements in Iceland be left undisturbed, unless the local naval

[546]

forces were materially strengthened, and on 16 June the War Department notified General Bonesteel to this effect. The "relatively insignificant strength" of the local naval forces, and "the fact that the Navy does not consider these forces as local naval forces but rather as a part of the fleet" were, according to the Operations Division, grounds for considering further, discussion of the matter inadvisable.33 The Operations Division reversed itself again on the very next day, when Admiral King proposed that aircraft of either service operating in support of the other should remain under the direct control of their own service but should have their tasks or missions assigned by the service in whose support they were operating. Discerning a similarity between this proposal and the Army-Navy agreement under which Army aircraft were operating within the coastal frontier areas, the Operations Division immediately countered with a recommendation that the language of the existing agreement in Joint Action of the Army and the Navy be employed in the present case. In a memorandum to Admiral King the following terminology was suggested:

The Army is responsible for the assignment of tasks (missions) to all U. S. aircraft engaged in the defense of Iceland. The Navy is responsible for the assignment of tasks (missions) to ail U. S. aircraft engaged in operations for the protection of sea communications and for the support of Naval forces in the sea areas around Iceland. Army aircraft are operated as part of the Iceland Base Command. Naval aircraft are operated as a part of the U. S. Fleet. When, however, aircraft of either service are made available for the support of the other service, such supporting aircraft, will operate under the principle of unity of command as set forth in Paragraph 10 of joint Action of the Army and Navy, 1935.34

Admiral King accepted the change, and with this the question was settled. General Bonesteel and the commandant of the naval base in Iceland were directed to revise their joint plan accordingly, which they did.

What had actually been agreed upon in Washington was little more than a reaffirmation of the general principle involved. The paragraph in Joint Action of the Army and Navy to which reference was made only defined the responsibility and limited the authority conferred by unity of command. Recognition on the part of both services that integrated operations might be necessary and that those circumstances would require a single commander was no doubt a long step toward a solution, but the final step -making it

[547]

obligatory for either one of the commanders in Iceland to place his forces at the disposal of the other- was not taken. Who should invoke unity of command and take over the reins was left for future determination.

Command relations with the British presented a situation somewhat similar to, and in some ways closely tied in with, the Army-Navy command problem. Like the latter it involved co-ordinating the operations of two different forces; it embraced an accepted, fundamental principle; and it raised the inevitable question who should command whom. Among the factors that had to be reckoned with were political considerations, the rate of progress in reaching an adjustment of the Army-Navy problem, and -before the Pearl Harbor attack-American neutrality. In Bermuda and the West Indies the defense responsibilities of the British Governors created a special complication. In Newfoundland, the special interests of Canada were affected. In Iceland the Royal Navy claimed "paramount interest." By and large the difficulty seems to have been not that forces of different nations, but rather operations in three different elements -land, sea, and air- were involved. More particularly the operations had different aims. The Navies -Canadian, British, and American- were engaged in a wide-ranging war of movement against German U-boats; the respective ground forces in Iceland and Newfoundland-indeed at all the Atlantic bases-were employed in preparing relatively fixed defenses against air attacks and possible hostile landings. The several air forces, which were capable of serving either purpose equally well, were generally the point of conflict. As soon as the United States entered the war, British and American ground forces in Iceland came under a single commander, for purposes of local defense; the British, Canadian, and American Navies joined forces to fight the Battle of the Atlantic under common direction; but the two types of operations never did meet, in the realm of command, even to the limited extent of the American Army-Navy agreement.35

The question of command, either between the United States and Britain or between the United States Navy and the Army, was one of those questions that by their very nature could be solved only by higher authority, not by

[548]

the individuals directly concerned. The drafting of joint plans for local operations was on the other hand a function of the local commanders, but local planning was at times hampered by the absence of firm and specific command arrangements. Defense preparations nevertheless had to be made in spite of the uncertainties of the command situation. After several weeks' respite, shipping in the western Atlantic began in January 1942 to feel the brunt of the German submarine campaign. Allied losses rose at an alarming rate. In addition, enemy air activity over the North Atlantic began to increase. The BOLERO movement, during the summer, brought a corresponding reaction from the Luftwaffe. Enemy or unidentified planes were reported over Iceland on eighteen occasions during August, which was only four less than the total number reported in the preceding three months, and on forty-seven days out of the sixty-one in September and October following.36 During midsummer a German meteorological party had installed itself on the northeast coast of Greenland. Although not actually located until the next spring its presence was soon suspected. Certainly countermeasures against the enemy could not be deferred until the problems of inter-Allied, or of Army and Navy, command were completely solved.

Bombers of the Newfoundland Base Command had been helping to fight the U-boats ever since the day, late in October 1941, when one of the B-17's of the command dove out of a layer of low lying clouds almost onto the deck of a German submarine. The one bomb that the plane had time to release missed the sub by a close margin. Four months later, at the beginning of March, planes from Newfoundland bagged the first two submarines to be sunk from the air by American forces, although in both cases the successful planes were naval aircraft from Argentia. Another four months afterwards, on 30 June, a naval patrol bomber based on Bermuda sank the third U-boat to fall victim to an American plane.37 These were the rare climactic moments. Day in and day out, weather permitting, the Newfoundland and Bermuda patrols made their routine sweeps without so much as catching sight of a submarine. Many a time they were sent out on a wild goose chase, or, to put it more precisely, in search of porpoises and whales. Only four submarines were sighted and attacked off Newfoundland in the first eight months of 1942; and five attacks were made on submarines that were not

[549]

AMERICAN FIGHTER PLANES OVER CAMP ARTUN, ICELAND

visible at the time. In the neighborhood of Bermuda three U-boats were bombed on sight and six others were attacked sight unseen.38

The men who in 1942 were fighting the Battle of the Atlantic from Army planes under Navy command were the real forgotten men of the war. Partly to blame was the fact that for months at a time nothing happened to break the monotony of their patrols, but also to blame were the shifting and sometimes confused lines of organization and command. After the Army Antisubmarine Command was organized in October 1942, their story became a part of the Army Air Forces' history. Until then they were neither fish nor fowl.

At the beginning of 1943 a heavy concentration of U-boats gathered in the North Atlantic just beyond range of the Newfoundland air patrols, but within reach of the still unfinished Greenland bases. Plans were cast to send a heavy bomber squadron to Greenland and to increase the air cover from Iceland; but the weather in the region of Cape Farewell was discouraging

[550]

COAST GUARDSMEN CAPTURE TWELVE GERMANS in a raid on the last enemy weather-radio station in Greenland.

to patrol operations from BLUIE WEST I. As a result action did not immediately follow upon design. Then, in March, the whole strategy of the war against the U-boat was placed under discussion at the Atlantic Convoy Conference in Washington, where it was decided to increase the range of the Newfoundland patrols and to place under Canadian operational control all the antisubmarine operations from Newfoundland. During the next few weeks two squadrons of B-24's were sent to the Gander airport to join the B-17 squadron that had been carrying the full load and on 3 April Canada took over operational control. Within two weeks the first steps were taken to set up an operating base at BLUIE WEST I. By this time the crisis had passed; the battle had moved away, and the long-range bombers were no longer needed in the North Atlantic.39

[551]

In Iceland, where the Army's main effort was against the Luftwaffe, the peak of activity was reached in the fall of 1942. The first engagement had taken place on 28 April and had been followed by a three months' lull. Then in late July three more encounters took place. Up to this point the honors had gone to the Norwegian patrol squadron, which, under RAF command, was operating off the northern and eastern coast; but it was not long before the American air forces in Iceland had their chances at the Nazis. Having missed being the first to engage the enemy, an American plane became the first to bring one down. On the morning of 14 August two American fighter pilots, Lt. E. E. Shahan and Lt. J. D. Shaffer, intercepted and destroyed a Focke-Wulf 200 about ten miles north of Reykjavík. It was the first German plane of the war to be shot down by the Army Air Forces.40 During the next two months American fighter planes of the Iceland Base Command bagged two more German planes, intercepted and attacked seven, and unsuccessfully tried to intercept three others. Planes of the Norwegian squadron, meanwhile, had met and attacked three German aircraft with varying degrees of success, and during the same period the ground troops opened fire on German planes a dozen times. A few planes appeared during the winter, but none was intercepted and only two came under antiaircraft fire. The spring of 1943 promised to be just as lively. In April German planes were spotted or reported on at least ten occasions. One of the intruders, a Junkers bomber, was shot down at the end of the month by two planes of the 50th Fighter Squadron. Throughout the year the number of enemy or unidentified planes reported was about 15 percent less than in 1942. Actual contacts were considerably fewer. Apparently the German planes were successfully avoiding the antiaircraft defenses and evading the American fighters. On 5 August American planes, making their second interception of the year, shot down another German bomber, the fifth and last enemy plane to be destroyed over Iceland.

Some of this air activity over the North Atlantic was undoubtedly related to the enemy's efforts to set up weather and radio stations in Greenland. Early in the spring of 1943 three members of the Greenland Sledge Patrol discovered the German weather base that had been established on Sabine Island the preceding summer. On being discovered, the Germans immediately descended on the patrol station at Eskimonaes, about fifty miles to the south, destroyed the place, killed one of the patrol men, and captured another. A third member of the patrol escaped to Scoresby Sound with the

[552]

news of the raid, which was dramatically confirmed some time later by the arrival of the man who had been taken prisoner by the Germans. He had persuaded them to split forces; had engineered an opportunity to be alone with the leader, had seized and overpowered him, and, turning the tables completely, brought him back to Scoresby Sound, a captive. A flight of bombers led by Col. Bernt Balchen took off from Iceland for Sabine Island on 25 May and found the enemy base of operations. Bombing and strafing the three or four huts that made up the installation, as well as a small supply ship that was discovered in the harbor ice, they left the place damaged and on fire. To follow up the air attack a Joint Army-Coast Guard task force was organized in Narsarssuak (BLUIE WEST I) and was dispatched as soon as ice conditions permitted, in July, on board the two Coast Guard cutters Northland and North Star. A specially trained and equipped detachment of twenty-six men and two officers made up the Army component. After a difficult three weeks' voyage by way of Iceland, where the North Star laid over for several days for repairs, the force arrived off Sabine Island on 21 July. Plenty of signs, but no Germans, could be found. Then just as the landing party was about to return to the ship, its attention was attracted by the sound of phonograph music. A lone German was discovered waiting to surrender. He was taken on board. Further search of the coast revealed nothing else, and it was assumed that the rest of the Germans had been evacuated or had moved farther north. After almost coming to grief in the heavy pack ice, the two cutters arrived back at the Hvalfjördhur (Iceland naval base in Mid September.41

Operations in Greenland were resumed the next summer with the discovery of a well-fortified German base just north of Sabine Island. A landing party of soldiers and Coast Guardsmen went ashore from the cutters Northland and Storis, but found the place deserted. A burned-out armed trawler lay abandoned in the ice. Some days later the Northland sighted and gave chase to a strange vessel, which proved to be another Nazi trawler and which was scuttled by its crew when capture seemed unavoidable. On this occasion twenty-eight German officers and men fell into the hands of the Coast Guard. Some of the men had belonged to the Sabine Island garrison the year before. Before the summer of 1944 came to an end, a second German base was assaulted and destroyed, and a large 180-foot trawler was captured undamaged. The total score for the two summers came to three

[553]

German bases leveled, two ships destroyed, one captured, and sixty-two enemy prisoners. 42

By the time the Greenland "campaign" reached its height in the late summer of 1944, Rome had fallen, Paris had been freed, and the Nazis were retreating toward the Rhine. In the Pacific the winning of Saipan and Tinian and the liberation of Guam had set the Japanese back on their haunches. In both the Atlantic and the Pacific the war had receded beyond the point from which it could seriously threaten the western hemisphere; but in its backwash there were swirls and eddies such as the operations in northeastern Greenland.

The problems that had come to the Atlantic bases with the coming of war to America had not displaced the old, pre-Pearl Harbor problems. Supply and transportation matters, regular mail deliveries, recreation and welfare, relations with the local authorities and with local civilian labor-all these were matters of almost as much importance after 7 December 1941 as before. Quite apart from their importance, they ceased to some extent to be problems. By the summer of 1942 the machinery for dealing with them was fairly well established. Likewise the new problems-the questions of defense, of reinforcement and replacements, of command relations-were not any of them particularly new. Active participation in the war only gave them higher priority. But they did not long enjoy their status. After the summer of 1943 the chief problem, except for the men engaged in routing the Nazis out of Greenland, was one of contraction, of reduction and redeployment. The enemy, not the Americas, was on the defensive, and the American outposts in the Atlantic shifted roles accordingly.

[554]

page created 30 May 2002