CHAPTER I

The Halt at the Meuse

At the beginning of September 1944, the American Third Army under the command of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton entered upon operations against the German forces defending the territory between the Moselle and the Sarre Rivers. These operations, which lasted well into December, were subsequently to be known, although quite unofficially, as the Lorraine Campaign. The troops under General Patton's command faced the Moselle line and the advance into Lorraine with an extraordinary spirit of optimism and a contagious feeling that the final victory of World War II was close at hand.1 They had just completed, in their pursuit of the enemy across northern France, one of the most successful operations in modern military history-and that with comparatively slight losses. Their present mission of driving through Lorraine was to be an important part of the strategy of advance on a wide front which had been laid down by Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, who on 1 September assumed direct operational command of the Allied forces in northern France.

Two corps, the XII and XX, were to take a continuous part in the battles for Lorraine fought by the Third Army. Both of these corps had participated earlier in the Third Army dash across northern France. The XV Corps, originally assigned to General Patton's command, fought for some time with the American First Army, but was to rejoin the Third Army during the latter part of September to take a brief though important part in the Lorraine offensive. Some of the divisions now with the Third Army were still licking wounds suffered earlier in Normandy and in the enemy counterattack at Mortain. The 90th Infantry Division had been badly mauled during the June fighting west of the Merderet River. The 35th Infantry Division had sustained some 3,000 casualties in operations at St. Lô, Vire, and Mortain. The 4th Armored Division had lost about 400 of its trained and irreplaceable armored infantry in July while holding defensive positions. But on the whole relatively few officers and

[1]

A series of happenings just at the close of August had acted

to heighten still further the spirits of General Patton's command and gloss

over the first sobering effects of the oncoming gasoline shortage. First, the

advancing army had captured the champagne caves and warehouses at Reims and

Epernay. It is unnecessary to dwell on the importance of this event. Second,

the Third Army had passed through the obstacle of the Argonne without a fight-in

spite of the gloomy and frequently expressed forebodings of the older officers

whose memories harked back to the bloody experiences of the AEF in the autumn

of 1918. Finally, with hardly a blow being struck, on the last day of August

Patton's tanks had seized Verdun, where scores of thousands had died in World

War I.

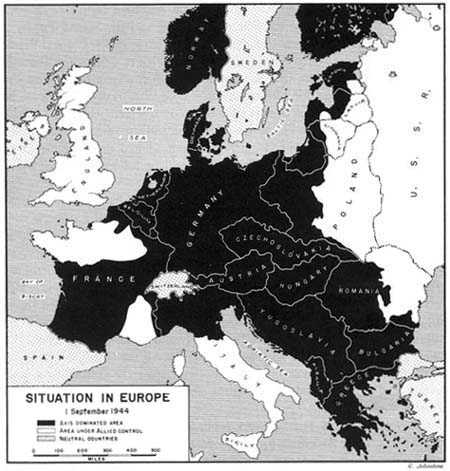

The last German troops west of the Seine River had been mopped up on 31 August; but in point of fact the area between the Seine and the Loire Rivers, designated in the OVERLORD plan as the "Initial Lodgment Area," had to all intents and purposes been secured as early as 25 August, ten days ahead of the OVERLORD timetable.2 By 1 September the Allied forces were across the Seine, not having met the stubborn and time-consuming opposition that had been expected at this river, and were moving speedily northeast and east of Paris in pursuit of the fleeing German armies. (Map I)* Thus far the Allied losses had been moderate, when viewed in relation to the territory won and the casualties inflicted on the enemy since 6 June. The build-up of the Allied armies in Northern France had been markedly successful. On the afternoon of 31 August the rosters of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), showed that a cumulative total of 2,052,297 men and 438,471 vehicles had landed in the American and British zones. Although losses and withdrawals had reduced this strength, at the moment General Eisenhower assumed direct command he had at his disposal on the Continent

[2]

General Eisenhower's 38 divisions were opposed, on 1 September, by 41 German divisions-5 of which were already penned in the coastal fortresses and the Channel Islands. An additional 5 enemy divisions were on the march to reinforce the German Western Front. Below the Loire River 2 reserve divisions were withdrawing from western and southwestern France. In Holland 1½ German divisions still remained in garrison.4 This apparent general parity between the Allied and German forces existed only on paper-and in the mind of Hitler. The ratio of combat effectives was approximately 2 to 1 in favor of the Allies. Hardly a German division was at normal strength. Most had sustained very severe losses in men and equipment. Many were badly demoralized as the result of constant defeats in the field. At no point since the Seine River crossings had any large German force been able to dig in and make a stand in the face of the persistent Allied pursuit. The Allied superiority in heavy weapons and motor transport was far greater than a comparative numerical tabulation of the opposing divisions would indicate. No complete materiel figures for this period now exist in either the Allied or captured German files, but the Allied superiority in guns was at least 2½ to 1, that in tanks approximately 20 to 1.5

[3]

On 31 August and 1 September Allied tanks and mechanized cavalry squadrons, operating far beyond Paris, seized crossings over the Somme, the Aisne, and the Meuse Rivers. The Allied left, formed by the two armies under the 21st Army Group (Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery), was moving rapidly in a zone about fifty-eight miles wide. In the north the First Canadian Army (Gen. H. D. G. Crerar) swept along the Channel coast in a drive aimed at the Belgian city of Bruges. On 1 September Canadian troops re-entered Dieppe, the scene, two years before, of one of the most heroic episodes in Canadian military history. The following day, Canadian tanks crossed the Somme River. To the south the Second British Army (Lt. Gen. Sir Miles C. Demp-

[4]

The Allied center, driving northeastward in support of the 21st Army Group, was formed by the First U.S. Army (Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges), which, teamed with the Third U.S. Army, comprised Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley's 12th Army Group. The First U.S. Army was making its advance in a zone some sixty-five miles across, with armored divisions pushed forward on the wings like prongs. On 31 August elements of Hodges' right wing were across the Aisne River and operating between St. Quentin and Rethel. The next day, however, General Hodges turned the VII Corps, which held the right-wing position, directly north, in a maneuver to trap the Germans who were retreating from the British front in the area west of Mons.

The Allied right, composed of two corps under General Patton's Third U.S. Army, was engaged in the eastward drive toward Metz and Nancy as a subsidiary to the main Allied effort being made in the northeast. The VIII Corps (Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton), also a part of General Patton's command, had been left in Brittany to reduce the Brest defenses and contain the other German coastal garrisons. By this time, however, the VIII Corps was so far removed from the rest of the Third Army that of necessity it had become a semi-independent force both for tactics and supply. General Patton's "eastern" front was about ninety miles in width. But in addition the Third Army held the line of the Loire River, marking the right flank of the Allied armies in northern France, which gave the Third Army front and flank a length of some 450 miles. On 31 August, Third Army tanks and cavalry crossed the Meuse River at Verdun and Commercy. By 1 September small cavalry patrols had arrived on the west bank of the Moselle River.

One hundred and seventy-five miles south of the Third Army, advance detachments of the Seventh U.S. Army were fighting in the vicinity of the great French industrial city of Lyon. (Map Ia) The Allied invasion of the French Mediterranean coast, begun on 15 August under the code name DRAGOON, auxiliary to the main Allied operations in northern France, had cut off the German garrisons in the port cities of Marseille and Toulon and pushed rapidly northward through the valley of the Rhone. The DRAGOON forces, under the tactical command of the commanding general of the Seventh Army,

[5]

On 29 August General Eisenhower had dispatched a letter to all his major commanders, outlining his intentions for the conduct of future operations. This letter reflected the optimism current throughout the Allied armies and the general feeling that now was the moment to deal the final and destroying blows against Hitler's forces west of the Rhine:

This letter directed the Allied commanders to undertake a general advance-an advance which in fact was already under way-but assigned the principal offensive mission to the British and American armies in the north. General Bradley, however, was ordered to build up incoming forces east of Paris, in

[6]

MAP NO. 1

preparation for a rapid advance toward the Sarre Valley designed to reinforce the main effort in the north and assist the Seventh Army advance "to and beyond Dijon."9 (Map I)

So rapid was the Allied advance and so complete the disintegration of the German field forces that by 1 September much of the instructional detail in the Supreme Commander's letter of 29 August was out of date. The Allied

[7]

During the preparatory period just preceding the Normandy invasion, General Eisenhower and the SHAEF planners had agreed on a strategic concept-eventually to assume the status of strategic doctrine-derived from the basic directive which the Combined Chiefs of Staff had given the Supreme Allied Commander: "to undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces."11 The ultimate goal, obviously, was the "political heart" of Germany-Berlin. But, it was agreed, the Third Reich had an "economic heart"-the great industrial center of the Ruhr. It could be assumed that the German forces in the West would concentrate to defend the Ruhr. Therefore, an Allied advance directed toward the Ruhr, if successful, would fulfill a dual mission, crippling beyond repair the German war production, and engaging and destroying the main German armed forces on the Western Front.

Geography offered four avenues leading from northern France to the Ruhr: south of the Ardennes, by way of Metz, Saarbruecken, and Frankfurt; straight through the Ardennes, on a west-east axis; north of the Ardennes, via Maubeuge and Liége; and through the plains of Flanders. But even before the Allied invasion SHAEF planners had ruled out two of the four possible avenues to the Ruhr because of their difficult terrain-at least insofar as the direction of the main Allied effort was concerned. Two approaches to the Ruhr still seemed feasible, although not equally so: the direct route north of the Ardennes and the circuitous route along the Metz-Saarbruecken-Frankfurt axis. On 3 May the SHAEF Planning Staff had reviewed the possible

[8]

The Supreme Commander's pre-D-Day decision to direct the main Allied attack along the route which led northeast from Paris to the lower Rhine and the Ruhr, via Maubeuge and Liége, could and would be defined in modern terms: the extent of terrain suitable for airfields, the number of flying bomb sites, and the war potential of the Ruhr. Additional factors probably had weight in this great strategic decision, even if applied subconsciously, factors that appeared only indirectly in planning papers but whose importance antedated fighter planes and Bessemer furnaces. The route along which Eisenhower intended to direct the Allied main effort had been through history the most important of the invasion routes between France and Germany. This military avenue had exercised an almost obligatory attraction in wars of modern date, as in those of earlier centuries. It provided the most direct approach to the heart of Germany. It presented the best facilities for military traffic, whether tanks, trucks, or marching columns. Although canalized, this approach to Germany followed terrain well suited to maneuver and debouched onto the level expanse of the North German Plain. The western entryways to the historic highway lay adjacent to the Channel ports, through which support for the Allied armies would come. The eastern termini gave direct access to the most important strategic objectives in Germany, the Ruhr and Berlin.

The Metz-Saarbruecken-Frankfurt route also had considerable historical significance and prior military usage. It should be noticed, however, that armies had taken this road in periods when the neutrality of Belgium and the Netherlands had checked maneuver farther to the north, or in a time before

[9]

Behind the pre-D-Day decision for a main drive on the northeast axis and a subsidiary thrust to the east lay the desire to secure the greatest freedom of maneuver and the most advantageous application of force by widening the front of the Allied advance. This line of thought had been stated in brief but precise form in the 3 May draft of post-OVERLORD plans:

In the weeks that followed the invasion, strategy bowed to tactics as the Allied armies fought to break out of Normandy and to secure the lodgment area between the Seine and the Loire. The beginning of the pursuit across northern France introduced logistical complications of a complexity which had not been anticipated in the strategic planning of the pre-D-Day period. The systematic development of a supply system adequate to support the type of orthodox advance envisaged in the OVERLORD plan failed to meet the requirements of the war of movement suddenly begun in August. The strategic

[10]

As early as 24 August General Eisenhower had written to Gen. George C. Marshall, the United States Chief of Staff, explaining the quandary in which he found himself: "For a very considerable time I was of the belief that we could carry out the operation of the northeast simultaneously with a thrust eastward, but later have concluded that due to the tremendous importance of the objectives in the northeast we must first concentrate on that movement." The objectives to which General Eisenhower referred were those which in earlier plans had long underscored the paramount importance of the northeastern approach to the Ruhr. In the first place the principal concentration of enemy forces in western Europe would be met in this area, including some divisions from the Pas-de-Calais strategic reserve which had not yet been fully committed against the Allies. Next, and highly important to the hard-pressed civilian population of London and southeastern England, was the opportunity to seize the CROSSBOW (flying bomb) sites in the Pas-de-Calais area before new and more-destructive missiles could be hurled across the Channel. In addition, a drive into western Belgium would give the Allies access to the best airfields between the Seine Basin and Germany proper, while denying these forward bases to the Luftwaffe. Finally, an advance astride the northeastern axis would bring the Allies to the deepwater port of Antwerp, which General Eisenhower and his operational and supply staffs regarded as "a permanent and adequate base," essential to further operations to and across the Rhine.13

Although General Eisenhower assigned priority to the northeastern operation, he was nevertheless unwilling to relinquish the idea of the subsidiary thrust to the east via Metz. On this point General Eisenhower and Field Marshal Montgomery were in fundamental disagreement. Montgomery categorized Eisenhower's strategic concept as the "broad front policy," his own as the "single concentrated thrust." The 21st Army Group commander's thesis, advanced in the last days of August and recurrent in various forms for some months afterward, held that the war could be brought to a quick conclusion by "one powerful, full-blooded thrust across the Rhine and into the heart of Germany, backed by the whole of the resources of the Allied Armies . . . ."

[11]

By 1 September the marked inability of the enemy to offer any really effective resistance and the speed with which the, highly mobile Allied formations were cutting in on the German escape routes led General Eisenhower to order a maneuver in which a part of the American forces would be turned to the north. In the Pas-de-Calais area west and north of the line Laon-Sedan, Allied intelligence estimated that the main German forces were grouped in a strength equivalent to the combat effectiveness of two panzer and eight to ten infantry divisions. General Eisenhower wished to engage and destroy this enemy concentration before driving on toward the Rhine and the Ruhr. Because Montgomery's divisions were insufficient for this task the Supreme Commander assigned two corps from the First U.S. Army to move north in the direction of Antwerp and Ghent, this maneuver, in conjunction with the British, being intended to trap the retreating enemy in the vicinity of Mons.

The execution of the maneuver to close the Mons pocket would shift the 12th Army Group center of gravity far from General Patton's Third Army, which at this time was deployed with its main body between the Marne and the Meuse Rivers. But General Eisenhower still was anxious to start the Third Army driving east as soon as the supply situation on the Continent would permit. On 2 September he called Bradley, Patton, Hodges, and Maj. Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg, the new commander of the Ninth Air Force, to his headquarters near Granville, outlined his plans for the proximate future, and indicated the role envisaged for the Third Army. He told his field commanders that as soon as the First Army forces had completed the move to the north

[12]

This last outlined the general directive under which General Patton and his Third Army would begin the sixteen-week Lorraine Campaign. But at this juncture in the victorious Allied march toward Germany the eyes of the high command-and the common soldier as well-were drawn irresistibly to the Rhine River, a goal seemingly close at hand. Following Eisenhower's statement of the over-all plan, Bradley sketched in the army plans, giving General Patton a future axis of advance calculated to take the Third Army across the Rhine in the Mannheim-Frankfurt sector. General Bradley added that two more divisions, the 79th Infantry Division and the 2d French Armored Division, would be given to the Third Army, but pointed out that Patton would not need the first of these divisions (the 79th) until after the Third Army was beyond the West Wall and attacking toward the Rhine.15 Such was the optimism prevalent in all echelons of the Allied armies at this stage of the war in western Europe.

In the middle of the afternoon General Patton telephoned the Third Army headquarters from the meeting of the commanders, giving orders that the army should not advance beyond the Meuse bridgehead line. Cavalry reconnaissance, he added, might continue to push to the east. These orders were promptly relayed to the commanders of the XII and XX Corps-gratuitously, it may have appeared to General Eddy and General Walker, whose forward formations already were immobilized at the borders of Lorraine by the shortage of gasoline.

The Third Army staff, as well as most of its combat formations, was by this time experienced and battlewise. General Patton's immediate headquarters was filled with men who had served as his staff officers in the Western Task Force and the Seventh Army during the North African and Sicilian campaigns. Many of them had come from the cavalry arm, as had Patton, and were thoroughly imbued with the cavalry traditions of speed and audacity.

[13]

GENERAL PATTON AND HIS CHIEF OF STAFF, Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey.

[14]

The chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey, was an armored expert who had served for a brief period as chief of staff of the II Corps while it was under General Patton's command in North Africa. He had subsequently commanded the 2d Armored Division in Sicily and in April 1944 had joined the Third Army in England, again as Patton's chief of staff. The deputy chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Hobart R. Gay, had been well known in the prewar Army as a horseman and cavalry instructor. Like many another cavalryman he had transferred to armor. He had been chief of staff for General Patton in both North Africa and Sicily. During the Lorraine Campaign General Gay and Col. Paul D. Harkins, who was the Third Army deputy chief of staff for Operations and had held the same post during the Sicilian campaign, were to act as Patton's closest tactical advisers.

Most of the other top-ranking members of the Third Army general staff had shared a common experience in the peacetime cavalry and armored force, in North Africa and in Sicily. Col. Oscar W. Koch, G-2, and Col. Walter J. Muller, G-4, had held these same positions on the staffs of the Western Task Force and the Seventh Army. The G-3, Col. Halley G. Maddox, a well-known army horseman, had been a member of the G-3 Section of the Western Task Force and then, in Sicily, had served as Patton's G-3. Only the G-1, Col. Frederick S. Matthews, was a newcomer to Patton's general staff. The Third Army special staff also included officers who had earlier served with General Patton in the same positions they now occupied: the Adjutant General, the Army Engineer, the Army Signal Officer, and the Army Ordnance Officer.16

General Patton had three army corps under his command at the opening of the Lorraine operation (VIII, XII, and XX). The VIII Corps, commanded by General Middleton, was still fighting in Brittany, far from the scene of the forthcoming campaign, and on 5 September would become a part of the new Ninth Army.

[15]

The XII Corps included the 4th Armored Division and the 80th and 35th Infantry Divisions. The 4th Armored commander, Maj. Gen. John S. Wood, was a onetime field artillery officer who had entered the young Armored Force in 1941 as an artillery commander. He was graduated from West Point in 1912 and in the course of World War I took part in the operations at Château Thierry and St. Mihiel as a division staff officer. General Wood and most of his officers had been with the 4th Armored Division, a Regular Army outfit, since the spring of 1942. During the lightning sweep into Brittany and the dash across France the 4th Armored won a considerable reputation and endeared itself to the heart of the Third Army commander. General Wood had already received the DSC on General Patton's recommendation.

Maj. Gen. Horace L. McBride, who commanded the 80th Infantry Division, was graduated from West Point in 1916 and later served as a field artillery battalion commander in the Meuse-Argonne offensive. He had joined the 80th Infantry Division, a Reserve formation, as its artillery commander. In March, 1943, McBride was promoted to command the division; he completed its training and brought it to Europe. The 80th saw its initial action in the second week of August during the battle of the Falaise pocket, but had sustained relatively few casualties. The 35th Infantry Division commander was Maj. Gen. Paul W. Baade, who had held this post since January 1943. A West Point graduate of 1911, General Baade joined the infantry, served on the Mexican border in 1914, and acted as a regimental officer in the Vosges and Verdun sectors in 1918. The 35th, a National Guard division, landed on the Continent during the second week of July. It received its baptism of fire at St. Lô and incurred severe losses there and in the Mortain counterattack.

[16]

Like the XII Corps the XX Corps contained one armored division, the 7th, and two infantry divisions, the 5th and 90th. Maj. Gen. Lindsay McD. Silvester's 7th Armored Division, an AUS formation, first saw combat during the pursuit across France but as yet had taken part in no major fighting. Although not a graduate of West Point, General Silvester had been commissioned as a Regular Army officer in 1911. His combat record as an infantry officer in World War I was outstanding: he had fought in all of the major American engagements, been wounded, and awarded the DSC. The 5th Infantry Division, now under the command of Maj. Gen. S. LeRoy Irwin, was a Regular Army division which had been sent to outpost duty in Iceland early in the war. The first elements of this division were committed in Normandy in mid-July, but thus far losses in the 5th had been small. General Irwin, a West Point graduate in the class of 1915, already had fought the Germans at Kasserine Pass and El Guettar in North Africa as artillery commander of the 9th Infantry Division. In December 1943, he was promoted to the command of the 5th Infantry Division. It may be mentioned in passing that such a transition-from artillery commander to division commander-would be a fairly common occurrence in the European Theater of Operations.

The 90th Infantry Division, a Reserve unit, got off to an unfortunate start in Normandy17 and by 31 August had an accumulated casualty list equal to 59 percent of its T/O strength. During August the 90th was settling into a veteran outfit under Brig. Gen. Raymond S. McLain, the division's third commander since D Day. General McLain, a National Guard officer, saw ac-

[17]

The Third Army numbered an estimated 314,814 officers and men at the end of August, including the three divisions and supporting troops assigned to the VIII Corps in Brittany.18 The first troop list for the Lorraine Campaign, issued on 5 September, shows five separate tank battalions assigned to the Third Army, which, added to the armored divisions, gave General Patton 669 medium tanks. Contrary to the flamboyant reports reaching the American press during this period, the Third Army could hardly be considered "top-heavy with armor"; indeed, during the month of September, the Third Army would average 150 to 200 fewer medium tanks than in the First Army. The troop assignments as of 5 September also included 8 squadrons of mechanized cavalry, 23 antiaircraft battalions, 15 tank destroyer battalions, 51 field artillery battalions, 20 engineer combat battalions, and 3 engineer general service regiments. However, the constant shifting of army and corps troops along the front would mean that on the average a lesser strength than that shown on the troop list of 5 September would participate in the Lorraine Campaign.

No appraisal of the Third Army strength at the opening of the Lorraine Campaign is complete without reference to the XIX Tactical Air Command. Although the XIX TAC did not "support" the Third Army but rather-according to regulations-"co-operated" with General Patton's troops, the tightly knit character of this air-ground team had already set a pattern for operations in the ETO. Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland, who had taken command of the XIX TAC early in 1944 after considerable combat experience with the 84th Fighter Wing, was held in high esteem by the Third Army commander and staff. The forward tactical headquarters of the two commands were kept close together. And at the morning briefings held in the Third Army war tent

[18]

AMERICAN COMMANDERS. Left to right: Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, 12th Army Group; Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland, XIX Tactical Air Command; Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Third Army. General Patton's dog, Willie, is shown in the foreground.

[19]

On 1 September the XIX TAC had in operation on the Continent two fighter wings, the 100th and 303d, comprising eight fighter-bomber groups and one photo reconnaissance group. The airfields used by General Weyland's 600 planes were distributed from the neck of the Brittany peninsula as far east as Le Mans. Since the Third Army had just overrun excellent Luftwaffe airfields in the Reims and Châlons-sur-Marne area the XIX TAC would be able, on 10 September, to move reconnaissance planes and some P-47's forward to the Marne.

During the penetration and pursuit phases of the Third Army's August drive the XIX TAC had been given three major tasks: (1) flying cover for the mechanized spearheads, together with air reconnaissance ahead of the ground advance; (2) sealing off the battlefield; (3) protecting the lengthy and exposed right flank of the Third Army. This combination of missions required a considerable dispersal of Weyland's squadrons; for example, on 1 September the XIX TAC was flying missions as far apart as Brest and Metz, while still other forays were being made 150-200 miles south of the Loire River. But although the speed and extent of the Third Army advance presented numerous problems in the matter of air-ground co-operation it also provided a wealth of targets for the American fighter-bombers. On 1 September XIX TAC was able to claim the largest bag of any single day since it had begun operations: 833 enemy motor vehicles destroyed or damaged.19 The kill on 1 September, however, would not be soon repeated. The following day poor flying weather intervened. Then, on 3 September, General Eisenhower ordered the Ninth Air Force-with the XIX TAC-to turn its main effort against the fortified city of Brest, nearly five hundred air-line miles away from the Meuse bridgeheads occupied by the Third Army, in an attempt to open that Atlantic port.

The Pause in the Third Army Pursuit

The seizure of bridgeheads east of the Meuse River on the last day of August marked the end of the Third Army's rapid pursuit across northern France. (Map II-inside back cover) The brief lull which now ensued, and

[20]

As early as 27 August the growing realization that the Allied armies had outrun their supplies and that there was not sufficient logistical support for a double-headed advance toward the east and northeast had forced the 12th Army Group to allocate priority in supply to the First Army, in accordance with the Supreme Commander's decision to strike toward Antwerp and the Ruhr.20 General Bradley visited General Patton on 28 August, discussed the unfavorable supply position, and then authorized the Third Army commander to continue the advance to the Meuse River if he deemed it "advisable and feasible." Patton had not even considered a halt short of the Meuse and the following day ordered his corps commanders to continue the drive eastward, General Walker's XX Corps to establish a bridgehead over the Meuse at Verdun and General Eddy's XII Corps to cross the river in the vicinity of St. Mihiel and Commercy.

At this time the Third Army was beginning to experience the first serious effects of a logistical situation which its own dashing successes had helped create. On 28 August the Third Army G-4 reported that the amount of gasoline received was markedly short of the daily consumption. General Gay noted in the Third Army Diary "a small bit of anxiety for the time," but in general the first reaction to the gasoline shortage was irritation rather than pessimism. General Patton took his supply problem to General Bradley's headquarters the following day but was told that the Third Army could expect no appreciable amount of gasoline until 3 September. General Gay wrote: "If this is correct ... the Third Army is halted short, of its objective, the Meuse River." Actually the Third Army had enough fuel in its leading armored columns to make the last jump which would carry the advance across the Meuse. There were no signs of any enemy determination to stand and fight, and when General Eddy raised the question as to whether he could allow his tanks to become stranded east of the Meuse General Gaffey assured him that the army commander would not object.

On 31 August, Combat Command A, of the 4th Armored Division (Col. B. C. Clarke), raced across the Meuse bridges at Commercy and Pont-sur-Meuse, three miles to the north, before the German rear guard could set off

[21]

Much ink has been spilled in varied and polemic explanations of the Third Army halt west of the Moselle River. For the historian it is sufficient to say that at this period the iron rules of logistics were in full operation and that the Third Army, making an attack subsidiary to the Allied main effort, would be the first to suffer therefrom.21

All through August General Patton's determination to override every obstacle and continue to advance had so inspired his army that it had violated with impunity many an accepted tactical or logistical dictum and had surpassed the most sanguine expectations of success. However, the Third Army successes in August had been matched all along the Allied front, in concrete results if not in brilliance. The total impact of these successes could not but disrupt a system of supply based on the expectation of a more gradual and evenly paced advance across France. During late June and the month of July determined German resistance had held the Allies to an exceedingly constricted area, making it impossible to carry out the scheduled and methodical forward movement of supplies, supply installations, and transportation facilities on the Continent. In August the great Allied advance had quickly regained the operational schedule which had been lost in Normandy and then had as quickly outrun it. Motorized and mechanized columns fighting a war of movement could function on a flexible tactical timetable. But the time element in the movement of low-priority service troops, cargo unloading, the creation

[22]

On 31 August the Third Army was 150 air-line miles beyond the line of the Seine, which, in the OVERLORD plan, was to have been attained by the Allied armies on 3 September. According to the more tentative phase lines laid down in the POST-OVERLORD Outline Plan, the Third Army forward positions on this date were at the phase line set for 2 April 1945 (D Plus 300), Obviously the phase lines set forth in the OVERLORD schedule had been tentative and hypothetical; they were probably even more so in the-case of the POST-OVERLORD timetable.22 Admittedly the papers showing these phase lines had been issued "for planning and procurement purposes only." But on this basis supply plans had been made, and improvisation in the field of logistics would prove to be far more difficult than in the sphere of tactics.

In the last days of August the Allied armies had reached the stage of "frantic supply." The bulk of all supply was still coming in over the Normandy beaches and being carried by truck directly from coastal dumps and depots to the combat zone. The beach areas were congested. An insufficient number of transport vehicles, coupled with the long haul from the beaches to the front lines, made it impossible to move supplies forward in the quantities required for the daily maintenance of the armies. The stalemate in Normandy and the hand-to-mouth supply in August had prevented the stocking of supplies between the Normandy coast and the army dumps. None of the Allied armies had been able to build up large operational reserves. The railroads west of the Seine had been crippled by Allied air bombardment in the weeks before D Day and could not be rebuilt overnight. The heavy landing craft shuttling between cargo ships and the beaches were busy bringing much-needed motor trucks ashore and could not be diverted to handling locomotives and freight cars. Pipe lines and pumping stations to carry gasoline forward took long in building; meanwhile gasoline was being drained out so fast for immediate use that the sections of pipe line which were finished could not be

[23]

The most telling shortages in this period were gasoline and transportation. As stores accumulated at the Normandy beaches and ports, the logistical problem turned on the allocation of transportation rather than on the allocation of the supply items themselves. Ammunition, which had a low priority in the unloading schedules then in force, presented no immediate supply problem, nor would it while the German armies were in retreat. Rations took a fixed but limited portion of the tonnage reaching the army dumps. During these days food would be monotonous-mostly K and C rations-but available in sufficient quantity. In the Third Army area the capture of the great Wehrmacht warehouses in and around Reims provided huge stores of beef, sauerkraut, and tinned fish, which added another kind of monotony to the army diet but freed some of the truck space hitherto given to rations.

At the end of August, Third Army trucks still were picking up their loads west of Paris, where the famous Red Ball Express had established the forward communications zone dumps, or were driving clear back to the beaches. The average round trip from the Third Army zone took three days. It was intended that the First and Third Armies would each have a supporting railroad. On 31 August a railway bridge was completed at Laval and rail operations were extended from Cherbourg to Chartres. But the first train movement to the Third Army zone would not commence until 6 September. The POL (petrol, oil, and lubricants) pipe line reached Alençon on 27 August, but it carried relatively small amounts of gasoline and was to have little immediate effect.23

Gasoline was the one item which was essential to further movement by the Third Army. The first severe impact of the supply shortage on Patton's operations had been staved off for a brief period when, on 26 and 27 August, over a thousand planes were used to fly gasoline and rations to the Third Army. On 28 August, however, gasoline deliveries were 100,000 gallons short of the daily Third Army consumption-an amount roughly equivalent to that used by one of Patton's armored divisions in a single day of cross-country fighting. On 29 August the Third Army was given priority on supply by air, and gaso-

[24]

The Military Topography of Lorraine25

That part of eastern France conventionally known as Lorraine roughly corresponds to the departments of the Meuse, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Moselle, and the Vosges-although the western part of the department of the Meuse and the southern section of the department of the Vosges lie outside of Lorraine. Historically, Lorraine represents the territories belonging to the three bishoprics (Trois-Evêchés) of Metz, Toul, and Verdun in the upper basins of the Meuse and Moselle Rivers. (Map III) Geographically, the area of Lorraine is more difficult to define and French geographers have never agreed on a precise and commonly accepted delimitation of its natural boundaries. In general Lorraine exists as a plateau, with elevations ranging from 600 to 1,300 feet. The western boundary may be designated by the Moselle valley, although some geographers extend the western limits of the plateau to the Meuse Heights (the Côtes de Meuse). From the viewpoint of military geography Lorraine is bounded on the east by the Sarre River, on the north by Luxembourg and the western German mountains, and on the southeast by the Vosges Mountains.

[25]

The sector of the Moselle toward which the Third Army faced at the beginning of September was reinforced by two nodal defenses-the outposts of Lorraine-one of which might properly be said to face west, one east. In the north the river line was barricaded by the so-called Metz-Thionville Stellung, a position based on the fortifications around Metz and Thionville. Originally built for the defense of France, these works had passed into German hands during the period 1870-1918 and again in 1940, with the result that the most modern parts of the Metz-Thionville system of fortifications were oriented to face the west. On the eve of 1914 the Germans had constructed two new works north of Thionville at Illange and Koenigsmacker, thus extending the original Metz-Thionville Stellung and further strengthening the line against attack from the west.

Thirty miles south of Metz lies Nancy, the historic ruling city of Lorraine. Unlike Metz the city of Nancy has never been fortified in modern times. The French had looked upon Nancy as a "bridgehead" from which their armies could debouch to the east, and had relied upon a combination of natural barriers and strong forces in the field to give it adequate protection. On the east Nancy is covered by a bastion of scarps and buttes, erupting from the Moselle Plateau, known as the Grand Couronné. On the west the city is protected by a triangular, heavily wooded, and rugged plateau known as the Massif de Haye. Still farther to the west the Moselle River swings out to pass around Nancy in a wide loop, adding one more barrier to defend the city. At the extremity of this loop the city of Toul guards the western approach to Nancy

[26]

Between Toul and Epinal, a little over forty miles to the southeast, an opening known as the "Charmes trough" (Trouée de Charmes) offered a western entry into Lorraine and the means of flanking the Metz-Thionville Stellung and the Nancy-Massif de Haye position. Prior to 1914 the French frontier defense system built by Gen. Sere De Rivières had purposely left this sector undefended as an open trap for the invading German armies. French military thought therefore had accepted the necessity of a "Bataille de la Trouée de Charmes," an action that finally took place in September 1914 and resulted in defeat for the Germans. In 1940 the German First Army followed this same path and outflanked Nancy, this time successfully. In 1944 the Charmes Gap still afforded a convenient route bypassing Nancy. But an advance from west to east would be made more difficult by the three major "M" rivers-the Moselle, the Mortagne, and the Meurthe-which formed traverses barring the exit from the "gap."

The Moselle River in particular is a military obstacle of no mean proportion. Unlike the neighboring rivers it has a high rate of flow and a relatively steep gradient. It drains the western slopes of the Vosges and during the rainy season is torrential and flooded. West of Nancy the Moselle valley is relatively narrow, but expands as it wends northward until, between Metz and Thionville, it attains a width of between four and five miles. North of Remich the Moselle enters a narrow, tortuous gorge, finally emptying its waters into the middle Rhine near Koblenz.

East of the Moselle, as has been noted, the plateau formation continues for some distances. Metz and Nancy lie close to the wide valleys of the Nied and Seille Rivers, known as "the Lorraine plain" (La Plaine). This rich, rolling agricultural region is interlaced with small streams, dotted with occasional woods and isolated buttes, and intersected at intervals by flat-topped ridges. Here are found the characteristic Lorraine villages, small, compact, and with buildings and walls of stone.

Moving from south to north across Lorraine, the following features, important in the course of the Third Army campaign, should be noted. Bisecting the southern section of Lorraine runs the Marne-Rhin Canal-between sixteen and twenty yards in width-which originates at Vitry-le-François and

[27]

The main Lorraine gateway on the northeast opens at the Sarre River, with its center at Saarbruecken and the gateposts in the vicinity of Saarlautern, on the left, and Zweibruecken, on the right. Beyond this opening the Hunsrueck tableland and the Hardt mountains rise to deflect any large-scale northeastward march to the Rhine Valley onto a flat-topped, forested plateau, known as the Palatine Hills (Pfaelzer Bergland). Beyond this plateau lie the Rhine Valley and the cities of Mannheim, Darmstadt, and Frankfurt. This gateway has always been important in the military topography of Europe. In 1814 the Allies took possession of Saarlautern in order to provide an immediate entry into France in case it should become necessary to deal again with Napoleon. In 1870 the main German armies crossed the Sarre in this sector to invade France and defeat General Bazaine's army at Metz. And here, in the period before 1940, Hitler had built the strongest section of the West Wall facing the strongest part of the Maginot Line.

Two main highways pass across Lorraine. One follows the old Roman road from Metz to Saarbruecken and thence to Mannheim. The other leads from Nancy, across the Vosges to Strasbourg. In general the area east of the Moselle is covered with an adequate road net, often hard-surfaced, which spreads out

[28]

The climate of Lorraine-due to play so important a role in the operations of the Third Army-tends to extremes of heat and cold, precipitation and dryness. The westerly winds do not lose their moisture until after passing over the plateaus east of the Paris Basin, with the result that two to three times as much rain falls in Lorraine as in the Champagne country just to the west. Weather records-which have been kept for a ninety-year period in Lorraine-show that in normal times the wet season begins in September and that October has the greatest amount of rainfall of any of the autumn and winter months. The average monthly precipitation in Lorraine during September, October, and November, is between 2.4 and 3.0 inches. In the autumn of 1944, however, the rain which fell on the underlying Lorraine clay was two and three times the amount usually recorded; in November 1944, 6.95 inches of rain fell during the month.27

The Enemy Situation on the Western Front

At the beginning of September 1944, the collective ground forces of the Third Reich numbered 327 divisions and brigades, greatly varied as to strength and capabilities. Of this total, in some respects a paper roster, 31 divisions and 13 brigades were armored. The confusion introduced in the German reporting system by the reverses suffered during August makes it difficult to determine what proportion of this strength was actively engaged on battle fronts. A careful study of the German situation maps maintained by OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres) and OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) indicates that elements of some 252 divisions and 15 to 20 brigades were deployed within the

[29]

In the five years of war that had elapsed since the invasion of Poland cumulative German losses had mounted to 3,630,274 men and 114,215 officers. The Army accounted for the largest share of these losses: 3,266,686 men and 92,811 officers. These enormous casualty figures included only the dead, the missing in action, and soldiers demobilized by reason of physical disability or extreme cases of family hardship. Nonetheless the numerical strength of the German armed forces still represented a relatively high proportion of the population, although the quality had deteriorated somewhat as conscription broadened to make good the earlier losses by reaching into older and younger mobilization classes, and as training periods of necessity were shortened. The total paper strength of the Wehrmacht, at the beginning of September, was estimated to be 10,165,303.

|

Army and Waffen-SS |

7,536,946 |

|

Navy |

703,066 |

|

Luftwaffe |

1,925,291 |

In actual fact the available fighting strength of the German ground forces was considerably below the total ration strength. This disparity had increased as the war progressed and was a continuing source of irritation to Hitler. The Field Army (Feldheer) now was estimated to number 3,421,000 officers and men. The Replacement Army (Ersatzheer), whose composition could be determined with a little more precision, totaled 2,387,973. Units of the Waffen-SS which were serving in the field independent of Army control had a strength reckoned as 207,276. The remaining million and a half members of the Army included miscellaneous Luftwaffe ground troops and SS personnel, police, foreign volunteers such as Italians, Indians, Frenchmen, and Spaniards, members of the services of supply, East European auxiliaries (Hilfswillige), and so forth. The greater part of the German Field Army was concentrated on

[30]

The months of June, July, and August had brought one German defeat after another on both the Eastern and Western Fronts. The resultant breakdown of communications, the loss or destruction of personnel records in hasty retreats, and the failure to retake the battlefields where the German dead and wounded lay made any strict accounting of battle losses impossible. Casualty tables dated in April 1945, but still incomplete at that time, give some idea of the losses inflicted on the Field Army in the summer disasters of 1944. In July the number of wounded who had to be hospitalized on all the German fronts was at least 1195,332, the largest total of seriously wounded for any month of the war. August was marked by the greatest number of killed and missing which the collective German Field Army would endure in any month of the entire war. Incomplete returns show 60,625 officers and men officially declared dead, and 405,398 missing. The mobility of the Field Army also had been gravely impaired in August, with the loss of 254,225 horses during the great retreats in the East and the West.

The Russian offensives against Army Group Center and the forces in the Ukraine had accounted for the largest proportion of German ground force casualties during June, July, and August: at least 916,860 dead, wounded, and missing. On the Western Front, where substantially fewer divisions were engaged on both sides of the line, the German Field Army had lost a minimum of 293,802 dead, wounded, and missing in the battles from D Day to 1 September. To this number may be added 230,320 officers and men of the Wehrmacht (86,337 of these belonged to the Field Army) who had retired into the Western fortresses, there to be contained with relatively small effort on the part of the Allies, and eventually to surrender.

At this late date it is impossible to give more than the approximate strength of the German armies in the West on 1 September. Casualty returns were only "estimates." The changes in the Replacement Army, following the attempt on Hitler's life and the appointment of Himmler to its command, seem to have caused extensive confusion and disorder throughout the replacement system. As a result the Germans themselves could not be certain as to the exact number of replacements sent to the Western Front during this period. They later estimated the fighting strength of the ground forces in the West on 1 August 1944, as 770,000 officers and men. Tables compiled at the same time for the status on I September give a fighting strength Of 543,000. These tables, how-

[31]

The heavy losses suffered in the West and the continuing high rate of attrition on the Eastern Front forced Hitler to provide some program for bolstering up the two main fronts with new or reconstructed divisions. In early July, while the Allies still were held in check in Normandy, Hitler had ordered the formation of fifteen new divisions to strengthen the German lines in the East and stem the Soviet tide. These fresh formations were obtained by utilizing troops returning to duty from the hospitals, drastically reducing the number of ground troops assigned to the Luftwaffe, converting naval personnel to infantrymen, enrolling new classes that had come of military age, and stripping industry of able-bodied men who previously had been exempted from the operation of the conscription laws. By the beginning of September, the fifteen new divisions and three "static" divisions had been raised and dispatched to the combat zones, fifteen of the total going to the East, two to the West, and one to Norway.30

During the early summer of 1944, Hitler and his closest military advisers had showed more concern with the collapse of the central section of the Eastern Front and the Soviet threat to East Prussia than with the Allied drive toward the boundaries of western Germany. The number of divisions engaged on the Russian front was much greater than the number engaged in the West. The Eastern theater of operations had been draining German resources since 1941. A long-continued, virulent, and effective propaganda had made the primacy of the struggle against "Bolshevism" an article of faith with the German people and the German Army. Equally important was the reliance which

[32]

Nevertheless, the rapid disintegration of the western German forces during August forced Hitler to turn his attention from the East and consider ways and means of shoring up the armies in front of the West Wall. It appears also that Hitler was already thinking in terms of some large-scale operation to regain the initiative, which had been everywhere surrendered. On 2 September Hitler gave instructions for the creation of an "operational reserve" of twenty-five new divisions, to be made available between 1 October and 1 December. Nearly all of these formations were destined for the Western Front.

The twenty-five new divisions and the eighteen raised in July and August now were designated volksgrenadier divisions, an honorific selected by Hitler to appeal to the national and military pride of the German people (das Volk). Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler and the SS were assigned the political indoctrination and training of these units, although they would not be included in the Waffen-SS, and Hitler personally concerned himself with attempting to secure the best arms and equipment for the new formations. Some of these divisions were assigned new members, generally in the "500" series. Many, however, would carry the numbers belonging to divisions that had been totally wrecked or destroyed, for on 10 August Hitler had forbidden the practice of erasing such divisions from the Wehrmacht rolls.

The organization and equipment of the new volksgrenadier divisions reflected the tendency, current in the German Army since 1943, to reduce the manpower in the combat division while increasing its fire power. Early in 1944 the standard infantry division had been formally reduced in strength from about 17,000 to 12,500 officers and men.32 The volksgrenadier division represented a further reduction to a strength of some 10,000, this generally being effected by reducing the conventional three infantry regiments to two rifle battalions apiece and paring down the number of organic service troops. Although equipment varied, an attempt was made to arm two platoons in each company with the 1944 model machine pistol, add more field artillery,

[33]

Although a desperate shortage of heavy weapons had forced Hitler to accept a Table of Equipment for the volksgrenadier divisions much weaker in antitank guns and artillery than he desired, he sought to remedy this weakness by ordering the construction of twelve motorized artillery brigades (requiring about 1,000 guns), ten Werfer (rocket projector) brigades, ten tank destroyer battalions, and twelve 20-mm. machine gun battalions. These GHQ (Heeres) units were intended to reach combat at the same time as the last twenty-five volksgrenadier divisions; most were slated for the Western Front.

In addition, ten panzer brigades were in the process of formation or just going into action on 1 September. Their equipment varied according to the ebb and flow of German industrial production, but in general these first brigades, numbered from 101 through 110, would be built around a panzer battalion that contained some forty Panther tanks (Mark V). As early as 26 June Hitler had ruled, on the basis of the German tank losses in Normandy, that the basic tank model, the Mark IV, should be matched one for one by the heavier Panther. Since even the most sanguine heads of the various German armaments offices were as one in agreement that the Third Reich could not equal the tank production of the United States, Hitler hoped to redress the armored balance on the battlefield by giving priority to the production of tank models tactically superior to the American Sherman. During July and August, therefore, the German factories stepped up the output of the Panther and the superheavy Tiger-the latter optimistically estimated to be equal to twenty Sherman tanks. In spite of the Allied air effort against German industrial centers, tank output during these two months fell only slightly short of production schedules, with tanks actually delivered as follows:

|

July |

August33 |

|

|

Mark IV |

282 |

279 |

|

Panther |

373 |

358 |

|

Tiger |

140 |

97 |

[34]

Still other drastic steps were taken in midsummer to meet the crisis in the West. Approximately a hundred fortress infantry battalions, made up of the older military classes and heretofore used in rear areas, were hastily and scantily re-equipped and sent forward to the field armies. About four-fifths of these battalions eventually would be sent to the West; by the beginning of September many were already in the line. On 4 September OKW took note of "the threatening situation" in the West and assigned priority on all new artillery and assault guns to that theater, following this with orders for a general movement of the artillery units in the Balkans back to the Western Front.34

Unlike the German high command of World War I, Hitler and his household military staff were unable to utilize fully the play of internal lines by shuttling divisions back and forth between the two main German fronts. Continuous pressure in the East and the West made it impossible to strip one front in order to reinforce the other, and, equally important, the great Allied air offensive against the railroad systems of Central Europe denied any rapid and direct large-scale troop movements.

In general the carry-over from the older Eastern Front to the newly opened Western Front would be indirect in nature. The survivors of divisions destroyed by the Soviet armies in many cases would be returned to Germany, there be used as cadres in the formation of new divisions, and finally be sent to the Western Front as the veteran core of these inexperienced formations. In addition, the long campaigning in Russia had produced a number of rank-

[35]

Hitler's intense and direct personal concern with every small detail involved in the preparation of new forces during the summer of 1944 was indicative of the degree to which the direction of the war had passed from the hands of the higher field commanders and the General Staff Corps to those of Hitler and his immediate entourage in the headquarters of OKW. The Polish campaign of 1939 had been fought by the field commanders and the General Staff planners in general accordance with the conventional German theories of command responsibility. In 1940 Hitler had intervened in the conduct of the campaign in France on two occasions, personally selecting Sedan as the point of penetration for the drive through the Maginot Line and personally halting the German armored formations from pursuing the British Expeditionary Force through the flooded areas in the Dunkerque sector.35 Up to this point in the war the prestige of the Wehrmacht generals and the German General Staff had been sustained by quick and easy victories. The reverses suffered on the Russian front during the winter of 1941-42, however, gave Hitler the excuse for entering more and more into the picture as the supreme military leader. Through 1942 and 1943 he tried to run the war from his headquarters in East Prussia. By 1944 Hitler's personal control over military matters was so well established that a general with the prestige of Rundstedt could not move an army corps a few miles without the permission of Hitler and the OKW staff. The unsuccessful attempt on Hitler's life in July 1944 ended most of what little influence the field commanders and the General Staff had managed to retain.

Now Hitler stood alone as the supreme arbiter in all phases of the German war effort, embodying in himself the "Fuehrer Prinzip" so long the core of

[36]

On the Western Front OB WEST36 exercised an illusory "supreme command" in the field under OKW. The relations between OKW and OB WEST, in the summer Of 1944, indicate the disrepute and desuetude into which all the field commands had fallen. Hitler and the OKW staff mistrusted the field commanders and sought evidence of treason in each defeat suffered at the hands of the Allies. Even successful operations, such as the Nineteenth Army withdrawal from southern France, more often than not would be rewarded with suspicion, calumny, and the relief of the commanders concerned. The field commanders and staffs were fearful for their lives at the hands of the Gestapo. When they visited the headquarters of OKW they found it chilling and aloof, with little knowledge of the conditions actually prevailing at the front and even less desire to learn. The atmosphere of distrust and suspicion corroded all sense of responsibility. The field commanders feared to exercise initiative and referred all important decisions to OKW. Orders emanating from OKW were seldom amended but were simply passed on to lower echelons with the remark "copy from OKW."

The disposition of command and decision in the person of one man, far removed from the practical considerations of the battle front, was evidenced in the late spring and early summer of 1944 by an almost complete abnegation of the principles of maneuver and mobility in the conduct of the war in France. From Normandy onward Hitler's idée fixe was that each German soldier in the West should stand his ground-even if this permitted the enemy to cut him

[37]

As a result of these Eastern Front experiences, Hitler had issued a long directive in September 1942 which contained the essence of the Hitlerian dogma on the unyielding defense and which still further stripped the German field commanders of authority and initiative. No army commander or army group commander, Hitler had written, could undertake any "tactical withdrawal" without the express permission of the Fuehrer. So far as the records show this order was never rescinded. In 1944 the precipitate German surrender of Cherbourg added to Hitler's innate distrust of the loyalty and courage of his commanders and provoked more diatribes on the "last ditch" defense. The results of this monomania were to deprive the German ground commanders of their chief operational concept-maneuver-at a time when Allied materiel superiority was stripping the German forces of the means of mobility in maneuver. Hitler's insistence on defending each foot of ground cost the German armies in the West dearly in men and materiel, but did not retard the pace of the August retreat across France. The German field commanders sought to protect themselves by a convenient formula, apparently first advanced by General der Infanterie Guenther Blumentritt, the chief of staff at OB WEST, which appears over and over again in dispatches to OKW: "Thrown back. Countermeasures are being taken." With the whole front in collapse Hitler could hardly single out the officers who ordered retreat.

At the beginning of September OKW sent a new Hitler "intention" for the conduct of the war in the West to Field Marshal Model, C-in-C West.37 In it Hitler ordered that the retreating German armies must stand and hold in front of the West Wall in a battle to gain the time needed for rearming the West Wall defenses, which in the years since the conquest of France had fallen into disrepair, but which he regarded as potentially impregnable. The holding line designated by Hitler ran from the Dutch coast, through northern Belgium, along the forward positions of the West Wall segment between Aachen and the Moselle River, and thence via the western borders of Lorraine and Alsace. A successful defensive battle along this general line, so Hitler reasoned, would have several important results:

[38]

(2) No German soil would be lost.

(3) The Allies would be unable to use the port of Antwerp, so long as the Schelde mouths were denied them.

(4) Allied air bases would be kept as far as possible from central Germany.

(5) The great industrial production of the Ruhr and the Saar would be protected.

This "stand and hold" order, like those issued earlier through OKW, showed little appreciation of the difficulties facing the German troops and commanders in the West. Field Marshal Model, who was now acting both as the C-in-C West and as the commander of the group of armies in northern France, Army Group B, had done what he could to convey to Hitler some sense of the crisis in the West, sending report after report to Jodl with the urgent plea that they be brought to Hitler's attention. On 24 August Model reported that the Allies had sixty-one divisions on the Continent, "all thoroughly motorized and mechanized," and that these ground troops were supported by 16,400 planes, of which a minimum of one-third to one-half could be considered operative at any given time.38 Five days later Model reviewed the rapidly worsening situation. The retreating troops, he warned OKW, had few heavy weapons and were mostly armed with carbines and rifles. Replacements and new weapons were lacking. The eleven German panzer divisions would have to be refitted before they could equal the strength of as many regiments; few had more than five to ten tanks in working order. The infantry divisions possessed only single pieces of artillery. The panzer divisions seldom had more than one battery. The horse-drawn transport of the German formations made for an unequal struggle with a fully motorized enemy. The troops were thoroughly depressed by the Allied superiority in planes and tanks. Finally, there now existed a wide gap between the two German groups of armies, Army Group B and Army Group G.39

On 1 September Model asked OKW for three fresh infantry divisions to cover this gap between the two army groups in the Lunéville-Belfort sector. OKW acceded to his modest demand, after some haggling, but on 2 Septem-

[39]

Finally, on 4 September, Model sent his last request to Jodl, this time urging that it be placed before Hitler "in the original." In this message Model painted a gloomy picture that must have been most irksome to Hitler, who at this stage in the war was prone to charge his field commanders with defeatism. In a detailed appraisal of the front held by the three armies under Army Group B, against which the bulk of the Allied forces were concentrated, Model estimated his "actual combat strength" as the equivalent of 3¾ panzer and panzer grenadier divisions, and 10 infantry divisions. Army Group B would need, he said, a minimum of 25 fresh infantry divisions and 5 or 6 panzer divisions.40 These estimates, it will be noted, took no account of the dire situation of the shattered divisions under Army Group G, now ending a long and costly withdrawal from the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean coast.

Model received no answer, for he was about to be relieved of his unenviable dual post as "Supreme Commander" in the West and commander of Army Group B. On 1 September Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt had been ordered to leave the rustic watering spot at Bad Toelz, where he had been taking the cure, and to proceed at once to Hitler's headquarters in East Prussia. This was not Rundstedt's first visit to the Fuehrer Hauptquartier. At the end of June 1944 Rundstedt, then in command of OB WEST, had journeyed to the Berghof at Berchtesgaden in company with Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, then commander of Army Group B. What the two famous officers told Hitler will probably never be known. Rundstedt and Rommel seem to have warned Field Marshal Keitel against continuing the war and may have said as much to Hitler. In any event Rundstedt was allowed to plead ill health and retire from his post; even Hitler dared not touch a man with Rundstedt's distinguished record of fifty-four years in the German Army. Rommel had returned to the front and there been injured. Lacking officers

[40]

Rundstedt's recall in September ostensibly stemmed from this untenable command situation. Other factors, however, were at work. Rundstedt had a reputation as a great strategist. He was well known to the troops, and his return to the front might be expected to give some much-needed encouragement. He had many friends in high places and although outspoken had rigidly adhered to the divorcement from politics which had characterized the old German Army. Rundstedt, therefore, would be returned to his old command as C-in-C West. Model, much to his own satisfaction, would be relieved and would retain only his position as the commander of Army Group B. Generalleutnant Siegfried Westphal, a young, energetic, and skilled staff officer, would be named Rundstedt's chief of staff. Westphal had fought the Allies in North Africa and Italy; during the latter campaign he had been chief of staff for Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring. His selection for the new assignment seems to have resulted from Hitler's conviction that General Blumentritt, the incumbent chief of staff at OB WEST, lacked the practical experience and ruthless energy necessary at this stage of the war.

From 1 to 3 September Rundstedt and Westphal were briefed by the OKW staff and cursorily by Hitler. Hitler expressed himself as unworried about the situation on the Western Front. He believed that the Allies were outrunning their supplies and would soon be forced to a halt. In any case the Allied advance was being carried by "armored spearheads." These could be cut off by counterattacks and the front would then be stabilized. The best opportunity to truncate these armored spearheads would be found in the vicinity of Reims, on the south flank of the northern Allied forces. Finally, like the OKW staff, Hitler stressed the importance and impregnability of the West Wall. His verbal orders to Rundstedt were brief: stop the Allied advance as far to the west as possible; hold Belgium north of the Schelde and all of the Netherlands; take the offensive in the Nancy-Neufchâteau sector by a counterattack toward Reims. The task assigned Rundstedt was formidable, but would be made somewhat easier by the fact that Westphal had succeeded in bringing Jodl to modify the "hold at all costs" concept which had so stultified all maneuver in the West.41

[41]

One of Rundstedt's first and most urgent problems-a problem he never completely solved-was the restoration of a collective strategy for the whole of the Western Front. (Map IV) Model had concerned himself almost entirely with hard-pressed Army Group B, on the German right wing, and had paid only cursory attention to the plight of Army Group G, on the left, or to the threat of a rupture along the thin security line that formed the only link between them. The counterattack ordered by Hitler against the south flank of the American Third Army might be expected to check the Allied thrust into this gap, but Rundstedt was none too optimistic of success in such a venture and warned that the forces needed could not be gathered before 12 September at the earliest.

In Rundstedt's opinion the Allied advance posed two additional threats to a collective defense on the Western Front. First, the Allies were pressing in the direction of the Ruhr industrial areas. Aachen and the sector of the West Wall covering the approaches to the Ruhr appeared to be particularly endangered. Second, the Allies possessed airborne forces that were not committed; Rundstedt agreed with Model's earlier estimate of the "acute threat" of an Allied airborne attack in the rear of the West Wall or east of the Rhine.

On 7 September Rundstedt forwarded his first estimate of the situation in the West to OKW, confirming Model's pessimistic reports. The C-in-C West estimated that the Allied forces in northern France and Belgium now numbered fifty-four divisions, "thoroughly mechanized and motorized." He predicted that there were at least thirty additional divisions in England-of which six were airborne. The German formations were extremely hard pressed and in considerable measure "burned out." They lacked artillery and antitank weapons. The Allied superiority in armor was tremendous-Army Group B had only about a hundred tanks fit for combat. Reserves "worthy of the name" were nonexistent. The sole reserves available were the "weak" 9th Panzer Divi-

[42]

The immediate effects of Rundstedt's report were negligible. Hitler reiterated that the Western Front must be spiked down and held as far to the west as possible, the shattered divisions in the line must be withdrawn and reconstituted, and the counterattack against the southern flank of the American Third Army must be made as scheduled.

Enemy Dispositions in the Moselle Sector

During the first few days of September the German front in the West had begun to stabilize itself somewhat, although a co-ordinated and homogeneous defense still was lacking along the four hundred miles between Switzerland and the North Sea. Logistical difficulties were harassing and impeding the advance of the Allied armies. A few fresh formations had arrived to reinforce the tired and disheartened German divisions. Furthermore, the German forces had now been driven back onto a system of rivers, canals, mountains, and fortifications which, although far from impregnable, favored the defender.

When Rundstedt assumed command on 5 September the paper strength of the combined German armies in the West showed a total of 48 infantry divisions, 14 panzer divisions, and 4 panzer brigades. Of this number, 13 infantry divisions, 3 panzer divisions, and 2 panzer brigades were close to full strength, although 4 of the infantry divisions in this category were encircled in fortress positions behind the Allied lines; 12 infantry divisions, 2 panzer divisions, and 2 panzer brigades were greatly understrength but still usable; 114 infantry divisions and 7 panzer divisions were "fought out" and of little or no combat value; 9 infantry divisions and 2 panzer divisions were out of the line and in process of rehabilitation and refitting.43

The bulk of these German divisions were grouped under Model's Army Group B, whose front extended from the North Sea to a point south of Nancy,

[43]

GERMAN GENERALS OPPOSING THIRD ARMY

Upper left: General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel

Upper right: Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz

Lower left: General der Panzertruppen Otto von Knobelsdorff

Lower right: General der Panzertruppen Hermann Balck

[44]

Hitler had intervened directly to nominate a new commander for the First Army, writing a personal letter to General Chevallerie, who had led the First Army during the withdrawal across France, relieving him on the grounds of "ill health." Chevallerie had been an infantry officer, a veteran of the Eastern Front.45 The new appointee, General der Panzertruppen Otto von Knobelsdorff, also was a veteran of the Russian campaigns but had an armored background. He had first commanded a panzer division on the Eastern Front and then had led three successive panzer corps. During the attempt to relieve the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, Knobelsdorff's corps had won considerable distinction-which may explain his subsequent appointment in the West. He was reputed to be a brave officer, had received several wounds, and as a corps commander had been much in the front lines. Hard, forceful, "steady in times of crisis," and an "unflinching optimist," Knobelsdorff possessed the characteristics that Hitler valued most. But his military superiors had agreed that he was "no towering tactician" and that he lacked somewhat

[45]

Friedrich Wiese, the Nineteenth Army commander, was an infantry officer. After fighting through the four years of World War I, he had become a police official and then, like many of the German police, had transferred to the Wehrmacht in 1935. Wiese made the Polish campaign in command of an infantry battalion and did not rise to division commander until the fall of 1942. A year later he was given command of an army corps on the Eastern Front, where he won a good reputation. In June 1944 Wiese was brought directly from the Eastern Front to assume command of the Nineteenth Army, then employed in watching the Mediterranean coast. During the retreat from southern France he had shown considerable talent as a tactician and was commended by his superiors for the dispatch with which he had oriented himself in the battle practices of the West.

Far superior in reputation to either Knobelsdorff or Wiese was Blaskowitz, the Army Group G commander. Since the First and Nineteenth Armies would be grouped under his command on 8 September, General Blaskowitz was to be the chief ground commander opposed to the Third Army in the first weeks of the Lorraine Campaign. An East Prussian, a stanch religionist, and avowedly nonpolitical in his affiliations, Blaskowitz, like his friend Rundstedt, represented the traditions of the old German Officer Corps. In October 1939 he had been promoted to command the Eighth Army. Subsequently he had spent the four years of occupation in France as commanding general of the First Army. On 10 May 1944 Blaskowitz had been raised, at Rundstedt's insistence, to command Army Group G. Actually Blaskowitz was already persona non grata at OKW, which attempted in various ways to limit his authority. This tacit antagonism seems to have stemmed from the fact that Blaskowitz was lukewarm toward the Nazi regime and had run afoul of Himmler in Czechoslovakia and Poland, provoking an enmity from the latter which would continually plague Blaskowitz in his conduct of combat operations. This old feud came to the fore again on 3 September 1944, when Blaskowitz protested a Himmler order, issued in the latter's capacity as chief of the Replacement Army, for the construction of a defense line that would be under Himmler's command immediately behind the battle front in the Nancy-Belfort sector. OKW in this case supported Blaskowitz' authority, possibly because of the imminent return of Rundstedt to the West. The latter

[46]

In the last days of August the First Army had retreated across the Meuse with a force numbering only nine battalions of infantry, two batteries of field guns, ten tanks, three Flak batteries, and ten 75-mm. antitank guns. Advance detachments of two veteran formations from Italy, the 3d and 15th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, had arrived in time to see some action during the withdrawal from the Verdun-Commercy line. The main bodies of these two divisions finally came up on 1-2 September and took positions along the east bank of the Moselle. During the retreat from Châlons-sur-Marne the exhausted 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division ("Goetz von Berlichingen") had been withdrawn to the First Army rear for rest and refitting in the Metz area. On 31 August, however, the situation had deteriorated so markedly that two battalions of the 17th SS hastily were gathered to form an outpost line west of Metz.