- Chapter X:

-

- Tactics And Tactical Decisions

-

- While General Buckner knew soon after

the initial landings that the Japanese had concentrated their forces on southern

Okinawa and had elected to fight the battle there, he did not then know the

true extent of these defenses. The strength of the Shuri fortifications was

first fully revealed in the heavy fighting between 8 and 23 April, when the

Japanese positions held against furious American onslaughts. Across the entire

front line evidence fast accumulated that the Japanese held tightly, from

coast to coast, a dug-in, fortified defense line, reaching in depth as far

as Yonabaru-Shuri-Naha. The failure of the American attack to break through

the Shuri line led to a review of the tactical situation and of the tactics

required to overcome Japanese resistance with the least possible cost and

time.

-

-

- Elements of Japanese Power

- As the Americans came up against the

Shuri line veteran fighters in the Pacific noted many familiar tactics and

techniques in the Japanese defense. Intricate and elaborate underground positions,

expert handling of light mortars and machine guns, fierce local attacks, willingness

of Japanese soldiers to destroy themselves when cornered, aggressive defense

of reverse slopes, full exploitation of cover and concealment, ceaseless efforts

to infiltrate the lines-all these were reminiscent of previous battles with

the Japanese from Guadalcanal to Leyte.

-

- The enemy had shown all his old ingenuity

in preparing his positions underground. Many of the underground fortifications

had numerous entrances connected by an intricate system of tunnels. In some

of the larger hill masses his tunneling had given him great maneuverability

where the heaviest bombs and shells could not reach him. Such underground

mobility often enabled him to convert an apparent defensive operation into

an offensive one by moving his troops through tunnels into different caves

or pillboxes and sometimes into the rear of attacking forces. Most remarkable

was the care he had lavished on positions housing only one or two weapons.

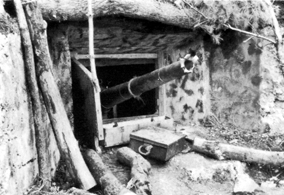

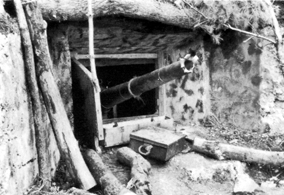

In one place a 47-mm. antitank gun

- [249]

- had a clear field of fire to the east

from a pillbox embrasure set into the hill and constructed of heavy stone

slabs and coral blocks faced with mortar; a tunnel braced with heavy timbers

ran from this embrasure fifteen feet into the hill, where it met another tunnel

running out to the north slope of the hill. A heavy machine-gun emplacement

near Oyama consisted of two pillbox-type dugouts looking out to the north,

strongly constructed and connected with the southwest slope of the hill by

a long, unbraced tunnel cut through the coral and lime formation. A cave 400

yards north of Uchitomari, with an opening only 3 by 4 feet, led into a 70-foot

tunnel that adjoined two large rooms and received ventilation through a vent

extending 30 feet to the top of the ridge. Some pillboxes had sliding steel

doors. Experienced officers described such positions as "both artful

and fantastic." 1

-

- The most striking aspect of the enemy's

resistance was his strength in artillery. Never had Pacific veterans seen

Japanese artillery in any such quantity or encountered such effective use

of it, especially in coordination with infantry attacks. Together with hundreds

of mortars from 50 mm. to 320 mm. the enemy had quantities of light and medium

artillery and dual purpose guns. He was strongest in 70-mm. and 75-mm. guns,

75-mm. and 150-mm. howitzers, and 5-inch coast defense guns. The 2d Battalion

of the Japanese 1st Medium Artillery Regiment, located initially south

of Kochi and Onaga, typified his artillery organization. It was composed of

three batteries, each with four 150-mm. howitzers, the best Japanese weapons

of that type, which could fire 80-pound projectiles at a maximum range of

11,000 yards. Each battery had four prime movers-6-ton, full-tracked vehicles

that could be used for hauling ammunition as well as for towing the howitzers

2

-

- Usually widely dispersed as defense

against American bombing and shelling, the Japanese artillery was nevertheless

closely integrated into the general tactical scheme of the Shuri defenses.

The keynote of the enemy's defensive tactics around Shuri was mutual support

through coordination of fire power. The enemy command indoctrinated the defenders

of each position with the importance of protecting adjacent positions as well

as their own. "It must be borne in mind that one's own fire power plays

an important part in the defense of the neighboring positions and vice

versa," a 44th Brigade order read. "If one's own

- [25]

-

12-cm. British gun in concrete emplacement

|

Concrete pillbox in hillside

|

Double pillbox, earth and bamboo

|

Tank trap across a road

|

Reverse-slope caves, two levels

|

-

- [251]

- NAVAL FIRE was directed into Japanese positions from all sides of

Okinawa. Here the U. S. battleship Maryland fires an after battery at

a target near southern tip of the island.

-

- AIR SUPPORT helped in taking some stubborn and inaccessible enemy

positions. This is in the Love Hill area above Yonabaru. Ridge from a

lower left to upper right opposing troops, with Japanese on the side where

bomb burst is seen

-

- [252]

- fire power is not fully brought to

bear, neighboring positions will be destroyed, and their supporting fire power

lost against an advancing enemy, thus exposing oneself to danger." 3

-

- Blowtorch and Corkscrew

- The American forces had brought to

bear against the enemy their great superiority in armor and self-propelled

assault guns, the weight of massed artillery, and supremacy in the air over

the scene of battle. Added to all this was something new to warfare. The continuous

presence of the tremendous fleet, aligned on the enemy's flanks, provided

the ground forces with the constant support of its great mobile batteries,

capable of hurling a vast weight of metal from a variety of weapons ranging

from rockets to 16-inch rifles.

-

- Naval gunfire was employed longer

and in greater quantities in the battle of Okinawa than in any other in history.

It supported the ground troops and complemented the artillery from the day

of the landing until action moved to the extreme southern tip of the island,

where the combat area was so restricted that there was a danger of shelling

American troops. Naval fire support ships normally were assigned as follows:

one for each front-line regiment, one for each division, and one or more for

deep-support missions designated by the Corps. Whenever possible, additional

ships were employed along the east coast to neutralize Japanese gun positions

on the Chinen Peninsula, which dominated the entire coast line of Nakagusuku

Bay and the left flank of XXIV Corps.

-

- Night illumination fires were furnished

on about the same basis as gunfire-one ship to a regiment, with additional

ships available to Corps for special illumination missions. The night illumination

provided by the ships was of the greatest importance. Time and again naval

night illumination caught Japanese troops forming, or advancing, for counterattacks

and infiltrations, and made it possible for the automatic weapons and mortars

of the infantry to turn back such groups. Often the Japanese front lines were

almost as well illuminated at night as during the daytime. It was very difficult

for the Japanese to stage a night counterattack of any size without being

detected.

-

- Many different kinds of ships were

used in providing naval support. A typical day would see the use of 3 battleships,

3 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, and 4 or 5 destroyers to support the Corps.

Later LCI rocket boats were used extensively. During the night of 18-19 April,

5 battleships, 1 heavy cruiser, 1 light cruiser, and 4 destroyers furnished

night fires and illumination. During the 19th,

- [253]

- BLOWTORCH-flame sears a Japanese-held cave.

-

- CORKSCREW-demolition team runs from cave blast

-

- [254]

- the day of the big attack, more heavy

naval gunfire was made available than usual. On call for each division were

q. battleships, 1 heavy cruiser, and 1 destroyer. In addition, 1 battleship,

1 heavy cruiser, and 1 destroyer were used for deep support behind the lines.

4

-

- Both carrier-based and land-based

air support was given the troops throughout the battle when weather conditions

permitted the planes to take to the air. During the first week all air support

was carrier-based, but after Kadena and Yontan airfields became operational,

Marine fighters gave daily support from these fields. The largest single air

strike of the Okinawa battle was on 19 April in support of the coordinated

attack. On this day 139 aircraft were used, most of them armed with 1,000-

and 2,000-pound bombs and rockets.

-

- Literally, the Japanese were enveloped

by fire power, from the ground in front, from the air above them, and from

the water on their flanks-fire power and explosives the like of which had

never before been seen in such concentrated form in so restricted an area.

Surely, all this fire power must have pulverized the Japanese positions and

rendered the enemy incapable of prolonged resistance. But it had not. The

enemy was denied freedom of movement, but even 16-inch naval shells as they

penetrated the surface concrete or coral and exploded sounded like ping-pong

balls to those who were kept deep underground.

-

- The American answer to the enemy's

strong and integrated defenses was the tank-infantry team, including the newly

developed armored flame thrower, and supported by artillery; each team generally

worked in close coordination with assaults of adjacent small units. Although

rockets, napalm, mortars, smoke, aerial bombing, strafing, naval bombardment,

and all the others in the array of American weapons were also important, the

tank-infantry team supported by 105's and 155's was the chief instrument in

the slow approach on Shuri. A captured Japanese commander of a 4.7-mm. antitank

battalion stated that in view of the success of this combination he did not

see why any defense line, however well protected, could not be penetrated.5

-

- A pattern of tank-infantry attack

had been developed in wresting the outer main ring of Shuri defenses from

the enemy. There the fighting had dissolved into numerous small-unit actions,

with assault groups of tanks and riflemen, demolition squads, BAR men, and

machine gunners, each trying by all the means their wits could devise, and

acting with high courage, to take a given

- [255]

- single position in front of them.

Guns and howitzers battered Japanese cave openings, dugouts, and pillboxes,

forcing enemy gunners back into tunnels for protection and decreasing their

fields of fire. Taking advantage of the resulting "dead spaces,"

infantry and tanks crept up on the most exposed strong point; the tanks attacked

the position point-blank with cannon, machine guns, and flame, while the infantry

prevented Japanese "close-quarters attack troops" carrying explosives

from closing in on the tanks. Once the troops gained a foothold in the enemy

position, they could move down on cave openings from above, in maneuvers which

the Japanese called "straddle attacks" and greatly feared.

-

- Each small action, a desperate adventure

in close combat, usually ended in bitter hand-to-hand fighting to drive the

enemy from his positions and there to hold the gains made. In these close-quarters

grenade, bayonet, and knife fights, the Japanese frequently placed indiscriminate

mortar fire on the melee. The normal infantry technique in assaults on caves

and pillboxes involved the coordinated action of infantry-demolition teams,

supported by direct-fire weapons, including tanks and flame throwers. Cave

positions were frequently neutralized by sealing the entrances. In some instances

Tenth Army divisional engineers employed a 1,000-gallon water distributor

and from 200 to 300 feet of hose to pump gasoline into the caves. Using as

much as 100 gallons for a single demolition, they set off the explosion with

tracer bullets or phosphorus grenades. The resulting blast not only burned

out a cave but produced a multiple seal. The complete destruction of the interconnected

cave positions sometimes took days.6

-

- The tank-infantry team waged the battle.

But in the end it was frequently flame and demolition that destroyed the Japanese

in their strongholds. General Buckner, with an apt sense for metaphor, called

this the "blowtorch and corkscrew" method.7

Liquid flame was the blowtorch; explosives, the corkscrew.

-

- Okinawa saw the use by ground troops

of important new American weapons: the armored flame thrower, Sound Locator

Sets, GR-6, and VT fuzes. The first was perfected at Oahu, after experimentation

by the Marines with cruder types, in time for use by the troops on Okinawa.

The 713th Tank Battalion was equipped with, and trained in the use of, the

new weapon, which was installed in the standard medium tank. The flame-thrower

gun was mounted in the 75-mm. gun tube and was operated under high pressure.

Fuel

- [256]

- tank capacity was 300 gallons and

effective range was 80 to 200 yards, although a maximum range of 125 yards

could be obtained. The fuel used was a mixture of napalm and ordinary gasoline.

Napalm is a granular soapy substance giving consistency and weight to the

mixture and restricting the area of the flame. The greater the quantity of

napalm, the heavier the viscosity of the mixture.

-

- The fifty-five armored flame throwers

of the 713th Tank Battalion were unloaded at Okinawa on 7 April and were attached

to the divisions. Although they were committed in the fighting Of 8-12 April,

they used only their machine guns and not their flame throwers. In the attack

of 19 April the Japanese experienced the full effects of this terrifying weapon

for the first time.8

-

- New sound-locator devices were also

used for the first time on Okinawa. Sound locator teams were rushed from Fort

Benning at the last minute to join the invasion. There were initially five

teams of eight men, with two Sound Locator Sets, GR-6, per team. The locators,

set up at each end of a base line about 100 yards in length, determine the

direction from which the fire of a gun is coming, locating the weapon by intersection.

One can then either place counterbattery over the general area, or else pinpoint

the weapon by aerial observation and destroy it by direct hit. 9

-

- The VT or proximity fuze, placed in

the nose of an artillery shell, consists of a tiny transmitting and receiving

radio set which automatically detonates a shell at a predetermined distance

from its target. The fuze transmits a radio beam, which, when it strikes a

solid object, is reflected by that object and picked up by the receiver of

the fuze. The beam then trips a switch within the fuze which detonates the

shell. The fuze was first used on 5 January 1943 by the Navy in the Pacific.

Employed first by the Army in the air defense of London in the summer of 1944,

the fuze was used in ground combat during the German break-through of December

1944 in the Ardennes. In ground combat against the Japanese it was first utilized

on Okinawa, in 105-mm., 155-mm., and 8-inch howitzers. Its most lethal effect

was produced by bursts over the heads of troops at a predetermined distance

above the ground. Trenches and foxholes provided little protection against

these bursts; the Japanese were safe from the fuze only when holed up in caves,

concrete pillboxes, tunnels, and other types of deep underground fortifications.10

- [257]

-

- The proved strength of the Japanese

defenses, and the costliness of reducing them even with the aid of so powerful

an arsenal of weapons as the American forces possessed, raised the question

of making an amphibious landing south of the Shuri line to envelop the enemy's

Shuri positions. It had been hoped that the 7th, 27th, and 96th Divisions,

supported by massed artillery, could penetrate the Shuri line.11

But failure of the attack of 19 April dispelled the expectation of an early

and easy penetration of the enemy defenses. If any doubt remained about the

kind of fighting that lay ahead before Okinawa could be won, it was dissipated

by the heavy combat and high casualties experienced from 19 to 24 April in

penetrating the first main ring of the Shuri defense zone. Even this gain

was small, and it was evident that it would take a long time to reach Shuri

at the rate of progress of the first three and a half weeks of the operation.

-

- The question of a second landing in

southern Okinawa was considered by Tenth Army most seriously before 22 April.

General Bruce, commander of the 77th Division, knew that his division would

be committed in the Okinawa fighting as soon as le Shima was secured. At Leyte

the amphibious landing of the 77th Division behind the Japanese line at Ormoc

had been spectacularly successful. General Bruce and his staff wished to repeat

the move on Okinawa and urged it on the Tenth Army command even before the

division sailed from Leyte. As the Ie Shima fighting drew to a close, General

Bruce pressed his recommenda-

- [258]

- tion to land his division on the southeast

coast of Okinawa on the beaches just north of Minatoga. He believed that it

would be necessary to effect a juncture with American forces then north of

Shuri within ten days if the venture was to be successful. His plan was either

to drive inland on Iwa, a road and communications center at the southern end

of the island, or to push north against Yonabaru.

-

- General Buckner rejected the idea.

His assistant chief of staff, G-4, stated that he could supply food but not

ammunition for such a project at that time. The Minatoga beaches had been

thoroughly considered in the planning for the initial landings and had been

rejected because of the impossibility of furnishing adequate logistical support

for even one division. The reefs were dangerous, the beaches inadequate, and

the area exposed to strong enemy attack. Although beach outlets existed, they

were commanded both by the escarpment to the west and by the plateau of the

Chinen Peninsula. The Tenth Army intelligence officer reported that the Japanese

still had their reserves stationed in the south. Both the 24th Division

and the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade were still in the area and

could move quickly to oppose any landings. Artillery positions on the heights

overlooking the beaches were fully manned. The 77th Division would be landing

so far south that it would not have the support of the troops engaged to the

north or of XXIV Corps artillery. (See Map No. III.)

-

- Moreover, at the time the 77th Division

was available, around 21 April, all three Army divisions in the line-the 7th,

27th, and 96th-were in a low state of combat efficiency because of casualties

and fatigue. The Tenth Army commander felt that it was of paramount importance

to relieve these divisions as far as possible in order to maintain the pressure

against the Japanese. Furthermore, the full strength of the 77th would not

have been available: the division had left garrison forces on the Kerama Islands

and le Shima which would not be replaced immediately. General Buckner felt

that any landing on the southeast coast would be extremely costly, "another

Anzio, but worse." Unless a juncture between the diversionary force and

the main body of his troops could be made within fortyeight hours of the landing

he felt that he could not endorse the plan. A juncture within such a period

of time being obviously impossible, the general's disapproval was patent.

-

- Looming even larger than the question

of where to commit the 77th Division was that of how best to use the 1st and

6th Marine Divisions in conquering southern Okinawa. The 2d Marine Division,

which had been sent back to Saipan, was scheduled to invade Kikai, north of

Okinawa, in July;

- [259]

- thus its employment on Okinawa was

to be avoided if possible. The 6th would not be available for the southern

front until relieved of its security mission in north Okinawa; this was effected

early in May by the 27th Division. The 1st Marine Division, however, could

be moved south to enter the line at any time, except for one consideration.

In Phase III of the original plan for ICEBERG, the island of Miyako, in the

Sakishima Group just north of Formosa, was to be invaded after Okinawa had

been taken. The V Amphibious Corps, scheduled for this operation, had suffered

so severely at Iwo Jima that Tenth Army was directed on 13 April to keep III

Amphibious Corps free from heavy commitment that would interfere with its

possible use at Miyako. Reconnaissance of Okinawa after the American landings

had disclosed that the island had far greater potentialities for development

as an air base than had been thought, and the strategical aspects of the entire

operation were therefore reconsidered. On 26 April Admiral Nimitz sent a dispatch

notifying Tenth Army that the Miyako operation of Phase III had been postponed

indefinitely by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, thus freeing the

III Amphibious Corps for full use on Okinawa.

-

- Doubtless in anticipation of this

decision, Tenth Army had already considered the problem of where and how to

commit the two Marine divisions standing by in northern Okinawa. Landings

on the Minatoga beaches were rejected for the same reasons as were adduced

in the case of the 77th Division. The beaches from Machinato airfield to Naha

were not considered suitable because their use would create supply problems

and because the strong Japanese positions west of Shuri overlooked the coastal

flat. The vicinity of Itoman farther south on the west coast was studied,

but the formidable reef there discouraged such a plan. The southern tip of

the island was sheer cliff along the shore. Landings along lower Buckner Bay

were considered impracticable because Japanese artillery on the Chinen Peninsula

and on the hills east of Shuri completely dominated the area and could prevent

naval gunfire support ships from entering the bay. The commanding general

of XXIV Corps Artillery believed that landings here would end in catastrophe,

that artillery could not be put ashore, and that if it could be, it would

be largely destroyed. In addition the time element was unfavorable: it would

take an appreciable time to obtain shipping from the 1st Marine Division and

mount it out, while the 2d Marine Division, which still had its shipping,

would have to be brought back from Saipan. If Marine troops were to be committed

in the south, it would be much quicker to move the 1st Marine Division down

the island by road to the established front.

- [260]

- SOUTHERN COAST LINE of Okinawa is marked by jumbled masses of rock

and vegetation, fronted by wide reefs. Cliff in picture is over 50 feet

high.

-

- [261]

- Later, about 26-28 April, three staff

officers of Tenth Army visited XXIV Corps headquarters and talked over with

Col. John W. Guerard, G-3, XXIV Corps, the tactical problems involved in committing

III Amphibious Corps to the battle in southern Okinawa. Colonel Guerard had

noticed that identifications of Japanese 24th Division troops had

been found during the past few days of fighting. These seemed to indicate

that the enemy command had moved the 24th to the Shuri front and that

the Japanese rear areas, accordingly, were more lightly held than formerly.

Colonel Guerard believed therefore that a landing in the south, to which he

had hitherto been opposed, was now feasible. He urged this view on the Tenth

Army officers and recommended landing the marines on the Minatoga beaches

at the southern base of the Chinen Peninsula. When informed of this discussion

by Colonel Guerard, General Hodge agreed that a landing of the marines in

the south was tactically desirable. Early the next morning General Hodge went

to Tenth Army headquarters to urge this view. The proposal was rejected on

the ground that a major landing in the south could not be supported logistically.

-

- Tenth Army staff officers, advising

against additional landings, contended that there were no suitable landing

beaches on the west coast; that it would be very difficult to supply even

one division on the southeastern beaches; that two diversionary landings,

one on each coast, would result in a dispersion of force with each division

being contained in its beachhead. They considered the entire plan too hazardous;

the troops would come up against strongly held Japanese positions in an area

where the terrain favored a strong defense, and the landings could not be

supported by artillery. General Buckner believed that the need for fresh troops

was greatest on the Shuri front, where they could relieve the battered divisions

already on the line.

-

- Relying on the advice of his staff,

General Buckner made his final decision against amphibious landings at some

time between 17 and 22 April; thereafter the matter, although raised again,

was not given serious consideration by Tenth Army. General Buckner came to

the conclusion that the .landings were not feasible either tactically or logistically.

Admiral Nimitz later flew with his staff members from Guam to Okinawa to confer

with General Buckner and other commanders present and concurred in the decision

which had been made.12

-

- The chief reason for the rejection

of a second landing seems to have been

- [262]

- logistical-the judgment that a landing

in the south could not be supplied. This judgment was confirmed during the

later stages of the campaign when the 7th Division, in possession of the Minatoga

area, was supplied by landing craft over the beach; despite the relatively

quiet conditions, the tonnage unloaded never reached a satisfactory level

because of the inherently unfavorable beach conditions, and landing craft

had to be supplemented by overland supply from Yonabaru. Aggressive forward

movement after a landing might have eased the initial logistical difficulties

but not to a very great extent. A second major consideration was the danger

that any beachhead might be contained by the strong Japanese forces in the

area. The truth was, indeed, that the Japanese fully expected and almost hoped

for another landing in the south, foreshadowed by the L-Day feint, and kept

a large body of alerted troops there to meet just such a contingency. After

having committed most of these troops to the Shuri front, they prepared a

substitute plan to oppose landings in the south, whereby from 2,000 to 3,000

troops in the area were to fight a delaying action while the main forces consolidated

a strong perimeter defense around Shuri.

-

- While before the end of April any

attempted landings in the south with one or two divisions might have failed-and

certainly would not have succeeded except with heavy losses-later the situation

became more favorable. The Japanese 24th Division was committed piecemeal

to the Shuri front between 23 April and 4 May, and the 44th Independent

Mixed Brigade was brought up on 26 April, although it did not enter the

battle immediately. These changes weakened Japanese strength south of the

Shuri line, and the Japanese counterattack of 4-5 May brought about a still

greater depletion of the enemy's resources. The prospect of success for a

southern amphibious landing thus greatly improved between 5 and 21 May; a

landing then would have been justifiable could it have been supplied. By that

time, however, the Marines had already been committed to the Shuri front.

Moreover, after Tenth Army turned the enemy's right flank on 21 May 13

there was no longer any need for a second landing.

-

- The Japanese command, expecting American

landings in the south and prepared to meet them, could not understand why

they were not made. The prevailing opinion among the Japanese was that the

American command wished to obtain as cheap a victory as possible by wearing

down the Shuri line rather than to risk troops in a hazardous landing in the

south, though the latter course might bring the campaign to a speedier end.

- [263]

- By their decision General Buckner

and his staff committed themselves to the alternative basic tactics of the

battle for Okinawa-a frontal assault by the two corps against the Shuri line

and an attempt to make a double envelopment of Shuri. The choice was a conservative

one: it avoided the risks inherent in another landing under the conditions

which would have attended it. It was definitely decided to bring the III Amphibious

Corps from northern Okinawa and the 77th Division from le Shima. Efforts were

also made to speed up the logistical preparations necessary for another general

attack. Until sufficient troops and supplies should be at hand the Tenth Army

would continue its attack against the second Shuri defense ring with as much

force as available resources permitted. For the time being the tactical aim

would be to consolidate and advance the American lines for the purpose of

gaining a better position for the big attack.

- [264]

page created 10 December 2001