CHAPTER III

THE ISLAND. 1638-1663

Before treating the settlements of Portsmouth and Newport, we should consider the general significance of the various proceedings in the colony of the Bay, which compelled the migrations to these places. There was a certain compulsive unity and largeness of principle involved in or evolved from all the jarring discords, proceeding from vagaries of theocratic government and the resultant consequences. Some two and one-half centuries have been required to grasp these occurrences, and to interpret them according to the accepted principles of enlightened history.

The banishment of Williams, the condemnation of Anne Hutchinson, the expulsion of Coddington—fellow of Vane—with a large company drawn from the better citizens of Boston, all these movements tended in one direction. On the other hand, the reversion of Coddington and the islanders toward conservative government evinced the constructive sagacity of English commons, the hereditary reverence for English law. Mrs. Hutchinson could not align herself with any established government, and soon migrated again to the Dutch settlements. Samuel Gorton’s career and his whole political action embraced both characteristics of this developing polity. Again, when Coddington’s judicial prejudices would have ended in actual “usurpation,” the sturdy, practical sense of these come-outers—whether from Massachusetts or Europe—repudiated him and reset the government on the concurrent action of the citizens.

46

Here was an idea, tending outward until held in and controlled by traditional law and its attendant institutions. It fermented again and again, leavening what it touched, until Roger Williams’ soul-liberty at last established itself under an orderly government, which was based on representation of the people.

Anne Marbury, of Lincolnshire, a parishioner and beloved disciple of Rev. John Cotton, in Boston, England, soon outgrew the parson’s teaching, for she assimilated theology and philosophy as readily as she took her mother’s milk. Moreover, according to Winthrop, she was a “woman of ready wit and bold spirit.” In intellect and vigor of temperament she would have been remarkable in any time or place; she was extraordinary when women were expected to listen humbly, and in no wise to create any function of their own. Nothing astonished her prosecutors and judges in Massachusetts more than her mastery of a situation, her speaking at will or holding her tongue under provocation.

She married William Hutchinson and migrated to the Bay in 1634. They occupied a house where the Old Corner Book Store now stands, and the dame’s parlor was soon a literal center of light and leading. Meetings and talks were held sometimes for women and sometimes for both sexes; illuminated gatherings, such as the Puritan world had never known. The Hutchinsons were “members in good standing” of the Boston Church, and the whole community were much exercised in controversy about “faith” and “works.” Governor Vane, John Cotton, with a majority of the Boston Church, Mrs. Hutchinson and her brother-in-law, Rev. John Wheelwright, upheld the former doctrine. Against them, there stood for “works,” Winthrop, Wilson the pastor (Cotton being preacher or teacher), and virtually all the clergy of the

47

colony, outside of Boston. Frequent disputes, intense excitement prevailed, yet the sensible Winthrop could say of the doctrines, “no man could tell, except some few, who knew the bottom of the matter, where any difference was.”

Any powerful current opinion tends to differentiate metropolitan and country politics. In December, 1636, Vane, claiming that the religious dissensions had been charged falsely to him, announced that he must return to England. The court arranged for a new election, when he changed his mind. In May following Winthrop and the “implacable” Dudley1 were elected Governor and Deputy. Boston could only return Vane and Coddington as Deputies. Vane could not withstand the strong and sagacious Winthrop, and sailed away for England.

The partisans of “faith” were now classed as Antinomians, and those of “works” as “legalists.” Agitation was developing new lines of division. Mr. Richman2 considers the crisis most interesting. “Was not the covenant of Works—i. e., Puritanism challenged to the death by the covenant of grace—i. e., by Antinomianism and Anabaptism; by the doctrines of the inward light, by the very spirit of Roger Williams, now in exile?”

The legalists determined to crush their opponents. In August, 1637, a synod at Cambridge condemned eighty-two “erroneous opinions” and nine “unwholesome expressions”; nice discriminations in heresy. The agitators conformed to the new phases of affairs, or were reformed

|

1 Dudley was technical Puritanism incarnate. In the “Magnalia” Cotton Mather says he had in his pocket these delightful verses:

The rhyme halts, but mark the exquisite harmony of church and state; and consider whether Roger Williams and a new state were not needed. 2 “Rhode Island—Its Making,” p. 46. |

48

altogether. Vane, as we have noted, wobbled and quit. Cotton, anxious for “his former splendour throughout New England,” ranged himself with the strong party in the state. Winthrop, too large a man not to love Roger Williams, was too fond of statecraft to be left outside the ruling element.

In the spirit of Dudley’s blessed harmony, the Court followed the action of the Synod. Wheelwright was banished. Then petitioners, who had dared to approach the authorities in his favor, were duly punished. Aspinwall was banished; Coggeshall having merely approved the petition, was disfranchised; Coddington, with nine others, was given three months in which to depart; others were disfranchised and fined; later, seventy-one more persons were disarmed. Note the bigness and the degree of the differing vials of wrath. Was the majesty of the great Jehovah ever more minutely parceled out, against his loving, if erring, children?

The trial of Anne Hutchinson in November, 1637, included all of this and more; as Mr. Brigham3 shows, the proceedings accorded better with “a Spanish inquisitorial Court” than with the ways of English law, for common forms were disregarded. Judge, prosecutor, and jury, if not always one, moved invariably as one against the unfortunate culprit, ordained and doomed to be a criminal. If a witness dared to speak for the defendant he was speedily intimidated. The moral atmosphere was fetid with despotic oppression. But Anne triumphed over all in the visible world. So long as she trod the firm earth she dominated Puritan parsons and ecclesiastical lawyers. She was passing through the ordeal—unscathed—when on the second day, unfortunately, she ventured into the unseen world of inward revelation and claimed to be

|

3 “Rhode Island,” p. 44. |

49

directly inspired. This boundless, infinite realm belonged to Puritan orthodoxy. Neither Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, the Pope, Mahomet, nor Buddha had any business in this exclusive precinct. Welde and his fellows of the prosecution seized this new and welcome opportunity. Then Coddington protested in a largely human way. “Here is no law of God that she hath broke, nor any law of the Country that she hath broke, and therefore deserves no censure.”4 All opposition was useless, and the sentence was banishment, to be deferred until May, 1638, when it was executed. Meanwhile the criminal was confined under the care of Joseph Welde.

The thorough and absolute working of the methods of the Bay is indicated in Cotton’s discussions with Anne’s son. He had protested that his mother was accused “only for opinion”; hence he was included with his brother in her sentence. Cotton amplified the judgment in this conciliatory preachment: “You have proved Vipers to eate through the very Bowells of your Mother to her Ruine.”5

The capable, illumined and virtuous woman was “excommunicate and delivered over to Satan.” We are not concerned with the success or failure of Antinomianism in Massachusetts. The matter is amply discussed by Charles Francis Adams.6 For the relation of such agitation to the history of the world we may cite Mr. Doyle, a competent observer: “The spiritual growth of Massachusetts withered under the shadow of dominant orthodoxy; the colony was only saved from mental atrophy by its vigorous political life.”7

|

4 “Prince Soc. Pub.,” Vol XXII., 280. 5 Richman, “Making of R. I.,” p. 123. 6 Three Episodes,” p. 574. 7 “Puritan Col.,” Vol. I., p. 140. |

50

The story of Anne may be completed here, for it has little further bearing on our theme. Exiled from the Bay, she went through Providence, with her family, and settled at Aquidneck. Her husband died in 1642. She soon removed to a spot near Hell Gate, controlled by the Dutch. With her household to the number of sixteen, she was murdered by the Indians in 1643; only one daughter survived.

We do not part so easily with our good friend Welde. He did not cease ministration with Anne’s life, and we must study his enlightened narrative of God’s land in this “heavie example.” I said these ministers possessed the infinite; witness how they entered into the inmost purposes of the Almighty. “I never heard that the Indians in those parts did ever before commit the like outrage upon any one family or families, and therefore God’s hand is the more apparently seene herein, to pick out this woful woman to make her, and those belonging to her, an unhearde of heavie example of their cruelty above all others.”8 This is not reporters’ talk; Welde and those like him were the interpreters of the religion of the time. There is in this epic, a bitterness of bite, a certain vitriolic essence of conviction that bigotry might admire in any age. We are forced to dwell on it, for some vagaries of the citizens of Rhode Island can only be imagined and apprehended when light is thrown on the shadows of their persecutors.

Some 200 persons were either exiled or laid under ban by the prosecutions against Antinomianism at the Bay, and they must seek a new home. Winthrop speaks of those “of the rigid separation and savoring of anabaptism, who removed to Providence.” Some were more conservative. John Clarke, an educated physician and very

|

8 Cited “R. I.—Its Making,” p. 151. |

51

able man, with others, was deputed to explore. They contemplated Long Island or Delaware Bay, but halted at Providence, where Roger Williams received them “courteously and lovingly.” Under his advice, they chose Aquidneck, after ascertaining it was not claimed by Plymouth. The Island was purchased March 27, 1637, by William Coddington and his friends from Canonicus and Miantinomi for forty fathoms of white peage, with five fathoms paid to a local sachem, together with ten coats and twenty hoes distributed to make diplomacy easy. The exodus stopped at Providence to make this civil compact: “The 7th day of the first month, 1638. We whose names are underwritten do here solemnly in the presence of Jehovah, incorporate ourselves into a Bodie Politick, and as he shall help, will submit our persons, lives and estates unto our Lord Jesus Christ, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords, and to all those perfect and most absolute laws of his given us in his holy word of truth, to be guided and judged thereby.—Exod. xxiv., 3, 4; 2 Chron. xi., 3; 2 Kings xi., 17.”9 It was signed by nineteen persons, including Coddington, Clarke, William Hutchinson, William Dyre, Henry Bull and Randall Holden.

In the eighteenth century Callender, in the nineteenth Arnold, agree that this body at that time were “Puritans of the highest form.” It is interesting to trace this migrating development. For if a state poised half way between the orthodox Bay and heterodox Roger Williams had been possible, it would have reared itself on the island of Aquidneck. This community had much that was lacking in Providence, as we shall perceive. The solid Judaic principles, affiliated by the Puritans and so important historically, are plainly visible. The King of

|

9 “Arnold,” Vol. I, p. 124. |

52

Kings was to govern by absolute laws in his holy word of truth. Evidently, a purified and sublimated theocracy was contemplated. There is nothing to show whether the compact at Providence based on “civil things” was considered—probably it was not. It had existed only about six months—moreover, it was not germain to the dearest convictions of the Aquidneck settlers. Clarke and Coddington—large men for their time—would “tolerate” Christians. Roger Williams—large for all time—had beaten through the jungle and undergrowth of sects, out into God’s open—where Jew or Gentile, Christian or Pagan could breathe freely. Likewise, all societies have based their institutions on property as well as on the activities of persons. Roger Williams in the turbulent community of Providence, had avoided as far as possible the limitations of property; in consequence much trouble resulted from neglect of some simple obligations of possession. Liberty—suddenly emancipated—had not learned that its best exercise was to be in and through the outcome of highly civilized social institutions. At Pocasset on the island, the settlers, especially those most influential and represented by Coddington, established necessary laws for maintaining the solid order of society.

We repeat that, if any half-way house in reaching a body politic had been possible, the Pocasset or Portsmouth settlement would have afforded proper opportunity. These men, bred as Hebraists and Puritans, driven out from strict Puritan lines, halted in their journey toward soul-liberty. In some respects their practical abilities surpassed Roger Williams; for their old and established principles of law, he was obliged finally to adopt into his colonial government. But the problem of a democracy administered according to liberty of conscience was not solved; it was only scotched at Portsmouth. It was

53

necessary to descend to the depths of no government with Roger Williams; and thence build solidly on the foundation of “only in civil things.”

The first settlement was at Pocasset, now Portsmouth, in 1638. Under the first compact, a complete democracy had enacted laws in the general body of freemen, the “judge” merely presiding. As in Providence, and before a year elapsed, this cumbrous democracy creaked. January 2, 1639, the freemen delegated power to the judge, assisted by his three “elders,” who should govern “according to the general rule of the word of God.” Reporting quarterly to the freemen, their administration could be vetoed thus: “If by the Body or any of them the Lord shall be pleased to dispense light to the contrary of what by the Judge and Elders hath been determined formerly, that then and there it shall be repealed as the act of the Body.”10 This system lasted four months; a most curious formulation of vox populi. This modulation of theocratic principles—whether autocratic or democratic—is most instructive.

The ultra democratic proceedings had offended Coddington and those who wanted an effective working government. A minority in numbers, which constituted the major strength and substance of the community, arranged to secede. The mother settlement at Pocasset, April 28-30, 1639, made a new compact as the “loyal subjects of King Charles in a Civill Body Politicke,” and elected William Hutchinson judge, with eight assistants. A quarterly court and jury of twelve was provided. This was the first government in the colony, moulded according to English law, and subject to the King. Theocracy and democracy were gradually being shaped to the common law, with its inherent obligations.

|

10 Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 47. |

54

Portsmouth preserved good records, and some details of the life there are interesting. As usual, the matter is chiefly of land conveyance, highways, administration of rates and such municipal affairs, with an occasional record of marriage, birth or death, but we get now and then a glimpse of something which interests more directly. For example:11 May 15, 1649, Adam Mott, having offered a cow forever and five bushels of corn by the year, “so long as the ould man shall live,” the neighbors, “every man that was free thereto,” made it up to forty bushels. Mr. William Balston, a prominent citizen, in consideration, agreed to give “onto father mott” for a year “house rome dyate lodging and washings”—quite an instance of social co-operation. Ear marks of cattle were frequently recorded, especially after 1650. The first entry is Sept. 1, 1645, of Edward Anthony—“a hind gad on the left ear.”

The immortal Pickwick was anticipated in debate July 16, 1650. In an action for slander before the town Court brought by John Sanford against Captain Richard Moris, the latter said “he had not nor Could not Charge the plaintiff to bee a thief in any Pticuler, and further sayd that if any words passed from him at Which Jeames Badcock (sic) tooke offence the said Captaine professed he knew not that he did speake any such words nether would he deny that he did but said if he did speake any such words it was in a passion and desiered mr Sanford to pass it by.” After such lucid apology everybody was satisfied.

In 1651, the “Clarke of the measuers” was ordered to inspect once per month that the “to peny white loafe way 16 ounces and beere bee sould for two pence a quarte.” For offense, forfeit 10s. In 1654 William Freeborne was

|

11 “Records of the Town of Portsmouth,” p. 40 et seq. |

55

allowed ten pounds “at the Rate of silver pay,” besides the cow and five bushels corn to “keepe ould mott” for the year. This included clothing for the beneficiary.

A prison was ordered to be built near the “Stockes” and a “doppinge stoole was to be sett at the water side by the po[ ]de.” This year was memorable in supervising and correcting the morals of this simple community. “In respect of several inconveniences that have ‘hapined,’ “it was ordered that no man sign a bill of divorce, unless the separation be allowed by the Colony; if offending, he should be fined £10. sterling. More significant was the ordinance that no man should harbor another man’s wife “after waringe,” and in case of offense, he should forfeit £5. sterling for every night.

Manners as well as morals were overlooked by these worthy burghers. In 1656 a committee, Mr. William Balaton, chairman, was appointed “to speake with shreifs wife and William Charles and George Lawtons Wife and to give them the best advise and Warning for ther own peace and the peace of the place.” We do not envy the selectmen for their responsibility in adjusting the disputes of these jangling females. Of larger public concern was a committee to procure the powder and shot ordered by the “generall Court” for Portsmouth. Roger Williams’ constant service in Colonial affairs appears; for the committee were to pay him for getting the ammunition. There are frequent admissions of persons as “freemen” or as “inhabitants.” There was also much detail in the management of the common lands; provisions against cutting timber, handling of cattle, etc. In 1660 William Baker petitioned the town to take his sheep and “Contrebute to his Nesesaty”; for which there was appropriated £8, “after the Rats of wompom 8 per peny,” for one year.

56

In 1662 at a meeting of “the free inhabitants of the Towne” a curious form of citizenship was made manifest. Peter Folger, late of “martin’s Vinyard, presented to the free inhabitants of this towne” a lease of house and land from William Cory, the said Folger shall have “a beinge amongst vs during the terme of the said lease.”

Adam Mott, who so thriftily arranged in 1649 for “ole father Mott” by giving a cow and five bushels corn per year toward his support by the town, died in 1661. His inventory showed £371.6, besides some land previously conveyed to his sons—a good estate for that time. Careful provisions were made to equalize the shares of the sons. The executors, Edward Thurston and Richard Few, were to receive each an ewe sheep for services. The widow was to have the “howsage and land” for life. The executors were to persuade her at her death “in ye disposinge of mouables with in howse or abroad to give it to them accordinge, to discretion whom beest desearues it in there Care and Respect to hir while she lives, vpon which my desseir is you will have your Eyes as my ffrinds, and harts Redey.” He instructs further “if my Children should be Crosse to there mother so yt it should force hir to marey againe. I give full power to my Executers to take good & full securitie for the makinge good of ye Estate so longe as she lives that my will may be performed.” This provision might cut both ways. Evidently, Mott’s immortal, marital obligations were to be as scrupulous as was his economic bargain with the town for supporting his father in old age.

Some prices may be noted, 4 oxen, £28; five cows and one bull, £30; one horse, one mare and colt, £36; 32 ewes, 2 rams, £32; 6 swine, £4. Wearing clothes, books, two suits, two doublets and breeches, one gown of gray cloth, and every day clothes, in all £11; 4 yards coarse

57

Kersey, £1; 8 pair stockings, £1.12; 1 feather bed and furniture, £6; various beds not included; 1 brass kettle, £7; 6 pewter dishes (14 lbs.), 1 quart, 2 pint pots, £1.6; iron pots, pans, etc., £3.14; 7 pair sheets, 2 table cloths, 6 napkins, pillowbers, £4; 2 tables, 1 joint stool and chair, £1.4; 1 cart and plow, 2 chains, £3.10; 1 hoe and axe, 2 scythes, 10s. The whole inventory indicates a comfortable household. And chairs were a luxury, as they were in Providence at the same period, where people were not as well off.

These proceedings are worthy of study. Doubtless, Newport was living in similar fashion, though the records are lost. Providence hardly shows so close, domiciliary superintendence; and there was no ecclesiastical interference whatever, such as generally influenced New England towns. The Portsmouth dwellers were Puritan in spirit and brought their lives to as rigid civic regulation as was possible. The common poor were cared for as usual, but the especial responsibility for those only half pauperized is very interesting. The minute discussions of these freemen and selectmen look petty now, but the whole way of life was hard and petty.

April 30th, Nicholas Easton voyaged around to Coaster’s Harbor, now the United States Naval Station. Following him, the seceders located southward, immediately erecting a house or houses. May 16, 1639, the first order recorded “the Plantation now begun at this Southwest end of the Island shall be called Newport.” The body politic of the new plantation, now established at Newport, negotiated with the more imponderable spirit hovering at Portsmouth. November 25th, after some communication back and forth, the Newport settlers made an order for courts, adopting the Portsmouth principle of allegiance to King Charles. They appointed two men

58

also to obtain “a Patent of the Island from his Majestie,” styling themselves as “the Body Politicke in the Ile of Aquethnec.” March 12, 1640, union between the two plantations was effected and the “brethren” at Portsmouth came in. Coddington was chosen Governor with William Brenton as Deputy. In the union, Newport took the initiative, and her political ascendancy prevailed in the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations for a century and a quarter.

The tendencies of the Coddington party toward strong government did not immediately affect the Newport plantation. In March, 1641, they could enact sensibly “the Government which this Bodie Politick doth attend unto in this Island, and the Jurisdiction thereof, in favor of our Prince is a Democracie, or Popular Government.”12 This democracy lasted until the union of the towns under the royal charter in 1647. In 1644, they adopted the name “Isle of Rodes, or Rhode Island.”13 The name according to Williams, as confirmed by the best modern research, is “in Greek an Isle of Roses.”14

The land system of the Island was like that of Providence generally, and an important act ordained in 1640-41 that, “none be accounted a delinquent for Doctrine: Provided it be not “directly repugnant to the Government or Lawes established.” The settlers at Portsmouth would have been Congregationalists had the ruling powers at the Bay permitted. Winthrop says, in 1639, “they gathered a church in a very disordered way; for they took some excommunicated persons, and others who were members of the Church at Boston and not dismissed.” And the lawyer Lechford, more orthodox than the parsons

|

12 “R. I. Col. Rec.,” Vol. 1, 112. 13 Ibid, 127. 14 Cf. Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 51. |

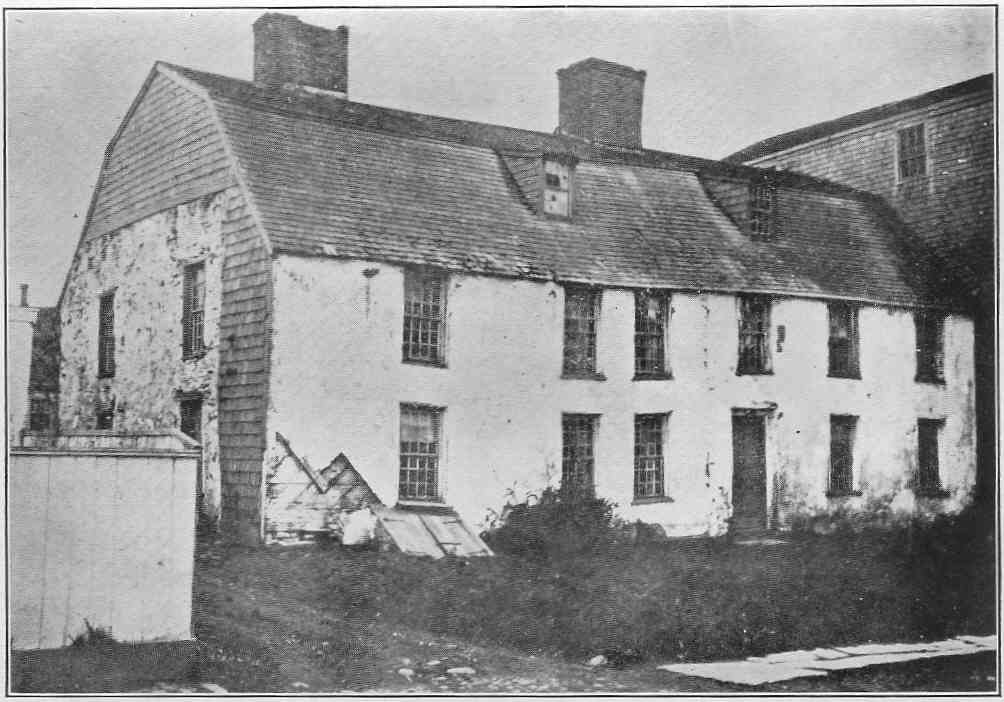

The Bull House, Newport. Built about 1640.

59

themselves, said, “no church, a meeting which teaches and calls it Prophesie.”15 John Clarke preached to the meeting. Winthrop said Anne Hutchinson broached new heresies each year, Anne being “opposed to all magistracy.” Yet in fact her husband was a magistrate at Portsmouth. As noted, a court in regular form was instituted there. Newport soon followed the example, and stocks, whipping-post and prison—the enlightened accessories of justice—were soon provided. The Puritans of the Bay could not report exactly matters which they in no wise comprehended. Richman thinks the impelling latitudinarianism fast drifted the would-be Congregationalists toward the Baptist or at least the Anabaptist view. Independency—little comprehended then—impelled Christians toward freedom for the believer and the separation of church and state. Roger Williams, “the time-spirit”16 was helped by unwitting instruments like Anne Hutchinson and Samuel Gorton.

Further evolution was going forward at Newport. In 1640, a “church fellowship”17 was gathered under the leadership of Dr. John Clarke and Robert Lenthall. This effervescing, doctrinal fellowship disagreed, Coddington and his friends adopting views which were to end in Quakerism, while Clark, and his followers formed a Baptist church in 1644.

In fact, the Island early developed stable institutions, which Providence lacked from the beginning. The Providence planters sought freedom of conscience, it is true; but historians sometimes forget that no community can live by spirit exclusively. So the old Massachusetts fisherman interrupted the exhorter, claiming that the English

|

15 “Plain Dealing,” p. 41. 16 R. I.—Its Making,” p. 136. 17 Keayne MSS., “Prince Soc. Pub.,” Vol. XXII., p. 401. |

60

emigrants crossed the seas to worship God, saying, “No, we came to live.” The land system at Providence afforded a good opportunity for new planters to become independent. Having acquired this material security, their varying views in theology tempted differences in social action. Some four-fifths of the community for many years would not directly assist the only church.18 Dissent apparently agreed only in further dissent. Political and social development necessarily halted. The desiderated pure democracy failed for lack of legislative and executive power,—whether in initiative or in restraint. Town meetings made poor substitutes for courts of law. As late as 1654, Sir Henry Vane remonstrated to Williams, “How is it there are such divisions amongst you? Such headiness tumults, injustice. . . . Are there no wise men amongst you, who can find out some way or means of union and reconciliation for you amongst yourselves, before you become a prey to common enemies?”19

The Plantations north and south were unlike as a yeast cake varies from a wholesome loaf of bread. Williams, educated and lofty—but not a political and social organizer—was alone in his university training; his neighbors, many of them able, were not instructed men. In Newport, Coddington, Clarke, Coggeshall, Jeffries, the Hutchinsons, were men of wealth and culture, eminent before they emigrated to New England. Among the very first schools supported by taxation in America was Lenthall’s “publick school” at Newport in 1640. In formal legislation, in courts, church and school, Newport was in advance of Providence. But let us remember, the yeast

|

18 Brigham, p. 55. 19 “R. I. Col. Rec.,” Vol. I., p. 285. |

61

cake has potentiality far beyond that of the developed bread.

It was in the future, in the domain unknown, that Providence was to excel.

None of the founders had more yeast in his make-up than Samuel Gorton, who was introduced in the Pawtuxet controversy and the interference of Massachusetts.20 In nature he was modern—if not the most modern of all the Puritan counter-irritants. We must now trace his first relations with our Plantations. Morton called him “a proud and pestilential seducer.” Perhaps it would be too much to say that condemnation by agitators at the Bay would now be sufficient praise, but all Morton’s direct charges have been disproved.21 The prosecution of Antinomians at the Bay was not agreeable to him, and he left for Plymouth. He defended a servant girl, whom he believed to be unjustly accused, and he was banished from Plymouth in December, 1638. The offense was mainly technical, for beyond all theological or legal differences, was his “exasperating spirit of independence.” True to the essence of English law—though an obstinate extremist—he protested against the methods of the court “let them not be parties and judges.” Driven out in a heavy snow storm, with his wife nursing an infant, he joined the exiles at Portsmouth. In defending a suit against another servant he fared no better, for he insisted that this court had no authority from the Crown. After much controversy, Governor Coddington summed against him. When he resisted, the Governor said, “All you that own the King, take away Gorton and carry him to prison.” Then Gorton exclaimed, “All you that own the King, take away

|

20 Ante, p. 38. 21 Brigham, p. 57n. |

62

Coddington and carry him to prison.” This retort direct could hardly accord with any course of law then possible on the Island. If the transcendentalist were the one individual in the universe, he would be complete. It has been urged reasonably22 that Gorton would rebel against any legal system the colonies could maintain; but we must consider his whole career and not any one technical point. He was a sincere individualist before the legal and social rights of such a creature were known—not a mere outlaw. In his letter to Morton23 he said simply, “I would rather suffer among some people than be a ruler together with them, according to their principles and manner of management of their authority.” He has outdone the patience of all historians; but let us handle him tenderly. It was this self-centered adamantine firmness in him and those similar—if not so able—which made of Rhode Island a rock in a shaken world; or a resisting government against theocratic systems and encroaching neighbors.

Coddington, supported by institutions, was not much .intimidated by the remonstrant. Gorton influenced a few comrades, and they migrated together to Providence, probably in the winter of 1640-41. He made some proselytes there, but the town would not grant him the privileges of a proprietor and citizen. Williams bewails the situation to Winthrop. “Mr. Gorton having foully abused high and low at Aquedneck, is now bewitching and madding poor Providence24 . . . some few and myself do withstand his inhabitation and town privileges.”25 He finally joined the Pawtuxet settlers and became a leading founder of Warwick, as has been noted.

|

22 Sheffield’s “Gorton,” p. 38. 23 Ibid. p. 8. 24 Cotton taunted Williams as being superseded “by a more prodigious minter of exhorbitant novelties than himself.” 25 Brigham, p. 61. |

63

Mystics rarely found sects and Gorton could not perpetuate himself. Yet, in himself he will always interest all students of individual development. Dr. Ezra Stiles heard and recorded the testimony26 of his last disciple, John Angell, in 1771. The actual memorials of Gorton’s life are not as important as the traces of his inevitable influence, as it affected other lives in the generations following him. We cannot read the poetic utterance of Sarah Helen Whitman, descended from Nicholas Power, an adherent of Gorton, or the philosophic writings of Job Durfee, as well as others, without recognizing that Rhode Island has drawn intimately and effectively from the sources of eternal truth. Mr. Lewis G. Jaynes has lately asserted27 sensibly that Samuel Gorton was the “premature John Baptist of New England transcendentalism,” the spiritual father of Charming, Emerson and Parker. When a mystic doctrine has penetrated and impressed a people, it needs no ecclesiastical formula or dogmatic foundation on which to rest. Active theology is the passing record of the time-spirit.

The winter of 1639-40 was memorable for the Island

|

26 “The Friends had come out of the world in some ways, but still were in darkness or twilight, but that Gorton was far beyond them, he said, high way up to the dispensation of light. The Quakers were in no wise to be compared with him; nor any man else can, since the primitive times of the Church, especially since they came out of Popish darkness. He said Gorton was a holy man; wept day and night for the sins and blindness of the world; his eyes were a fountain of tears, and always full of tears—a man full of thought and study—had a long walk out through the trees or woods by his house, where he constantly walked morning and evening, and even in the depths of the night, alone by himself, for contemplation and the enjoyment of the dispensation of light. He was universally beloved by all his neighbors, and the Indians, who esteemed him, not only as a friend, but one high in communion with God In Heaven.”—Col. R. I. H. S., Vol. II., 19. 27 Richman, “Rhode Island—Its Making,” Vol. I., pp. 108, 109. |

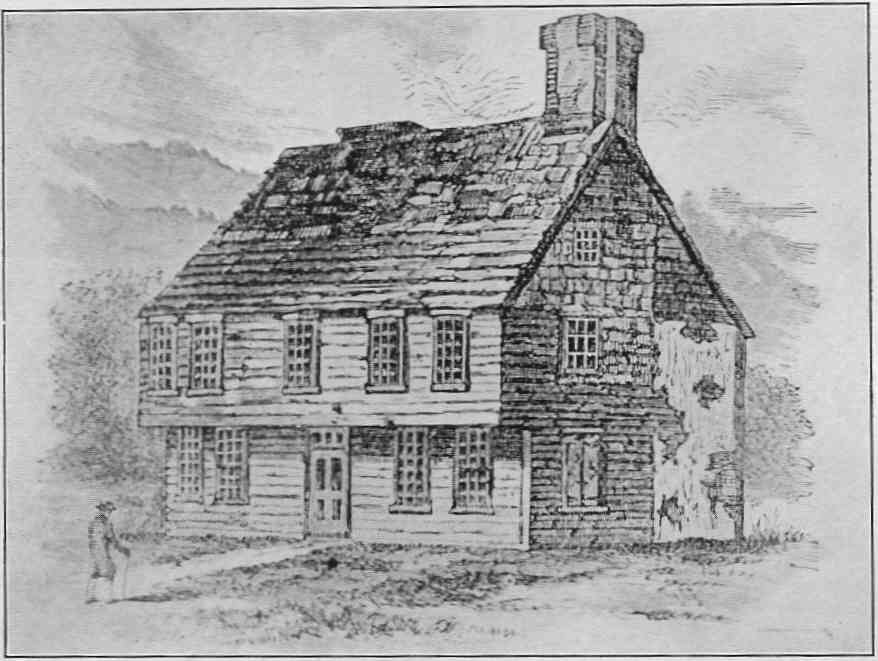

Coddington’s House at Newport, about 1650.

64

in scarcity and privation. For 96 people there were only 108 bushels of corn to be divided. Lechford visited in this or the following year and estimated the population at 200 families. Mr. Richman thinks 200 persons would be more likely and considers that Providence had about one-half as many.28 At this time the Bay sent three “winning” men to negotiate with members absent from the Boston church and sojourning on the Island. The settlers refused to treat, as one Congregational church had not authority over another.

Coddington tried to obtain recognition from the United New England Colonies in 1644 for the Island government. The United Colonies would receive the petitioners only as a portion of Plymouth Colony. He failed as an executive and direct leader of men, as we shall see in the “Usurpation.” He could not comprehend the people as it existed in any form of popular expression. Mr. Richman terms the government sought by Coddington an “autocratic theocracy.” Perhaps the record justifies this discrimination, but it is hard to treat Coddington justly from the records existing. He was a man of substance materially and mentally. He could not follow Gorton or even Williams in their efforts for social order—all of which were disorderly vagaries to him. Judge Durfee considers that the well-organized judiciary of the Island, locally adapted “betokens the presence of some man having not only a large legal and legislative capacity, but also a commanding influence.”29 It was probably Coddington. “Whoever he was, he was certainly after Roger Williams and John Clarke” a principal benefactor of the infant colony. It is more than doubtful whether Rhode Island could have attained a stable government

|

28 “R. I.—Its Making,” p. 131. 29 Hurfee, “Judicial History of R. I.,” p. 6. |

65

without Coddington’s effort or something equivalent.

Coddington and Captain Partridge made a definite proposal in 1648 to the Commissioners of the United Colonies to submit the Island to them, and would even place it under the jurisdiction of Plymouth. This scheme did not succeed. Coddington, according to Doctor Turner,30 would be a monarch, and, going to England, strangely succeeded in obtaining from the Long Parliament a commission, making him “in effect the autocrat of the fairest and wealthiest portion”31 of our territory. In 1651 he established himself in his “Usurpation,” and this constitutes a remarkable episode in the history of our state.

Shipbuilding began early at Portsmouth, and there was built there or at Newport in 1646 a ship of 100 to 150 tons for New Haven. She made an ill-fated voyage under Lumberton and was lost. In 1649 Bluefield, with his crew of Frenchmen, came into Newport and sold a prize. The authorities would not allow him to purchase a frigate of Capt. Clarke, as they feared the pirates would attack our coastwise commerce. These transactions show that a commercial market was well established already.

The West Indies needed the products of any rich agricultural region, and the fertile lands of the Island furnished the required exchanges. The sugar-mills used horses and these appear in Coddington’s exports in 1656.32 These West India goods were sold to Connecticut and to the Dutch at Manhattan. Then as always, the central port of Manhattan affected all American trade.

|

30 Brigham, “R. I.,” pp. 87-89. 31 Arnold, “R. I..” Vol. I., 238. 32 “R. I. Col. Rec.,” Vol. I., 338. |

66

Our commercial intercourse was important, and the name “Dutch Island,” at the mouth of the Bay, leaves a trace of it. Cross marriages occurred, and an occasional Dutch name in early Providence indicates the intercourse.

There was considerable trade with Connecticut, and the influence of this intercourse is shown by Isham and Brown in the type of houses adopted at Newport. The Coddington House, built possibly in 1641, and certainly before 1650, was an example of the comfortable dwelling which succeeded the early log house of New England. Though rude in appearance, it was certainly substantial and serviceable, or it would not have survived until 1835. It had an end chimney and the second story overhung, as in houses at London and elsewhere in England in the early seventeenth century. The Henry Bull house, dating from 1638-40, had the central chimney, distinctive of the better class of houses in Connecticut.

This early commerce of Newport, exchanging the rich products of the Islands so profitably, promoted comfortable living for the settlers accordingly. When Providence had no blacksmith, Newport had three, with masons, joiners, coopers and cordwaniers. Jefferay’s Journal notes that the houses in Newport about 1650 were as “yet small with few good ones.” Some had glass from England, with furnishings like the “old home,” but inferior. They had a few books, a little plate, and their dishes were mainly of wood or earthenware. Their tables, chairs and beds were rude, excepting the few brought from over sea.

During some two years of the “Usurpation,” there were virtually two governments in the colony, often conflicting with each other.33 Coddington’s commission was revoked in England and the formal news was brought by William

|

33 Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 93, a full account. |

67

Dyer to Rhode Island in 1658. Among other negotiations for a suzerain, the usurper had coquetted with the Dutch at Manhattan. This proceeding materially helped Williams and Sir Henry Vane in their efforts with the Parliamentary Commission for the revocation.

Perhaps nothing more clearly reveals the strangely inhuman and ferocious sentiment prevailing in Massachusetts at this period, than their wanton persecution of the Quakers, or Society of Friends, as they finally became. Such cruelty was not a necessary outcome of the Puritan spirit of government, for Connecticut, an orderly commonwealth, did not actively persecute in the name of Christianity. That community was unfriendly and banished Mary Dyer from New Haven for preaching in 1658; but they did not whip nor hang these heretics. Bradstreet and the Commissioners of the United Colonies in September, 1657, addressed this gentle request to the Governor of Rhode Island: “ . . . to preserve us from such a pest the Contagion whereof (if Received within youer Collonie were dangerous, &c., to bee defused to the other by means of the Intercourse, especially to the places of trad amongst us; which wee desire may bee with safety continued between us; Wee therefore make it our Bequest that you Remove those Quakers that have been Received, and for the future prohibite theire coming amongst you.”34 The conscience of Rhode Island was hardly worth considering by Boston magistrates. But evidently these governors thought that a direct thrust at the pocket by threatening “trad” might touch an universal passion and move the deepest springs of civilized feeling. The Rhode Island outcasts did not regard the appeal to covetousness, but answered immediately through Governor Benedict Arnold, “We have no law among us

|

34 “R. I. C. R.,” Vol. I., p. 374. |

68

whereby to punish any for only declaring by words their minds concerning the things and ways of God.”35

Fines, the jail, whipping-post and gallows were used to reform these simple believers, and they throve upon such severe regimen. Mary Dyer, a devout and much respected woman of Newport and Providence, was arrested in Boston and executed on the Common, June 1, 1660. When expecting death, she said, “It is an hour of the greatest joy I can enjoy in this world. No eye can see, no ear can hear, no tongue can speak, no heart can under stand, the sweet incomes and refreshings of the spirit of the Lord which now I enjoy.”

The large incoming of the Quakers was an important factor in the early prosperity of the colony. Many leading men like Coddington embraced their doctrines, and their social influence can hardly be exaggerated. Anabaptists and Antinomians, all ready for assimilation, often adopted the better formulated ideas of Fox and Barclay. While the majority of Friends were not learned in the schools, their whole system was a severe method of mental discipline. Their complete self-repression, their close study of the Bible, their gentle manners, all affected profoundly the ways of a new community. Rhode Island lacked the regulated ecclesiastical methods of Massachusetts and Connecticut. But we may remember that, while it lost much in a positive way, it gained somewhat by not having to unlearn. Compare the above utterances of Bradstreet and Mary Dyer. For a century, until the schools of our colony were regularly developed, the culture of the Friends was education in the concrete.

Significant evidence of the increasing trade of Newport appears in the immigration of wealthy Jews, the harbingers of active commerce throughout the world. A

|

35 “R. I. C. R,” pp. 374-380. |

69

large immigration from Lisbon came in 1655 and fifteen families came from Holland in 1658.36 They brought besides capital and mercantile skill, the first three degrees in Masonry. Religious freedom admitted them, but they would not have settled where there was not an abounding trade. Their people were to become an important element in our colonial life, and they appeared before the General Assembly by petition in 1684.

John Hull, the mint master, Major Atherton and others purchased of the Indians the southeastern portion of the Narragansett lands, to be known as the Pettaquamscutt Purchases. John Winthrop, the younger, obtained a charter from King Charles II., giving Connecticut jurisdiction over all Southern Narragansett. This movement in London was checked and reversed by the timely, discreet and vigorous action of John Clarke, our agent there. He convinced the King’s advisers, the Earl of Clarendon especially, of the injustice to Rhode Island, in this contemplated extension of Connecticut over her territory. Clarke obtained the liberal charter “to hold forth a lively experiment,” which was adopted by the whole colony in 1663.

This royal patent became the basis of colonial government and carried Rhode Island through the struggle against the Crown of Great Britain. Then the independent state went into the American Union, and the Charter lasted until 1843. Granting liberty of conscience to its citizens, it governed first a remote colonial dependency, then a state warring for independence, then a commonwealth merged into a great republic. In all, this document stood for one hundred and eighty years, certainly establishing a brilliant chapter in political history. Whatever the vagaries of the small commonwealth—and

|

36 “Mag. Amer. His.,” Vol. VI., p. 456. |

70

they were many—it pursued an onward political development, proving that an orderly state might exist without theocratic control of the individual citizen. Person and property were safe.

Our charter37 with its fellow given Connecticut in the previous year formed a new departure in royal government. The early colonial charters, following the example of Spain, had been commercial adventures. It is at least doubtful whether any political initiative was intended in the incorporation of Massachusetts in 1629. Massachusetts assumed such power, organized towns and courts, levied taxes and enacted laws for persons and property, most efficiently, even if done in a way only half legitimate. The American political efficiency—superior to every emergency or accident—showed itself in the germ.

Recognizing these great facts, the revolutionary parliament, influenced by Vane and the personal persuasion of Roger Williams, granted Rhode Island in 1644 splendid powers for political initiative and religious freedom. The King was very liberal to Connecticut in 1662 and went farther in the Rhode Island patent of 1663. In this negotiation, John Clarke, more practical than Williams, seized every opportunity to ally himself with the most liberal religious thought of continental Europe, as well as of England. There was not religious toleration at home, but for his distant colony the King pronounced this extraordinary manifesto:38 “Our royal will and pleasure is that no person within the said colony at any time hereafter, shall be anywise molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion in matters of religion, and do not actually disturb the civil

|

37 Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 102 et seq. 38 Cf. “R. I. C. R.,” Vol. II., pp. 3-21. |

71

peace of our said colony . . . any law, statute or clause therein contained, or to be contained, usage or custom of this realm, to the contrary hereof, in any wise, notwithstanding.” The divine right of Kings for the nonce justified itself, for here was perfect religious liberty bestowed through an executive decree. Simple and natural as the King’s action appears to-day, it seemed almost revolutionary to statesmen then, as Roger Williams reported in plain terms:39 “This, his Majesty’s grant, was startled at by his Majesty’s high officers of state, who were to view it in course before the sealing, but, fearing the lion’s roaring, they crouched against their wills in obedience to his Majesty’s pleasure.” Sagacious as Charles was, he built better than he knew, when he allowed absolute freedom of conscience in the little dependency of Rhode Island.

John Clarke laid his topographical lines as skilfully as he negotiated politically. Wisely basing his claims on title by Indian purchase, he kept the land away from Massachusetts and Connecticut, seeking to encroach on either side. The north boundary was the south line of Massachusetts; the west along Connecticut and downward to Pawcatuck river; on the south the ocean including Block Island; the island of Rhode Island and three miles to the east and northeast of Narragansett Bay—substantially our present territory. Great disputes with the larger Puritan colonies concerning boundaries on either side, distracted the next half century; but Clarke’s positions were so well chosen that they held the territory.

If George Bancroft was correct in affirming that more ideas finally becoming national have proceeded from Rhode Island, than from any other colony, we should consider well the “livelie experiment” in John Clarke’s

|

39 “Letter to Mason,” Narr. Club. Pub., Vol. VI., p. 346. |

72

charter. In the process of organization and development, Mr. Foster’s dates and definitions are significant.

1636-41. Providence, Portsmouth, Newport were distinct sovereignties.

1641-47. Providence, Aquidneck, Warwick were distinct sovereignties.

1647-51. Colony Providence Plantations was a distinct commonwealth.

1651-54. Providence, Warwick (the mainland), Portsmouth, Newport (the island), were a distinct commonwealth.

1654-86. Colony Providence Plantations was a distinct commonwealth.

Mr. Richman40 remarks that Providence disliked authority from any source. Newport sanctioned authority only when it proceeded from itself. Portsmouth was like Providence. Warwick varied, but approached Newport in theory.

We dwell on these features not so much for the technical divisions, as to mark the distinguishing characteristics of the novel ways of state-making. Williams, Clarke, Coddington, Gorton all appear in the varying life of the towns. The planters, seeking a civic structure, forced their will into submission to the larger principles of government and gradually methodized a citizenship under the royal government.

|

40 “R. I.—Its Making,” p. 309. |