73

CHAPTER IV

THE COLONY AND THE TOWN OF PROVIDENCE. 1648-1710

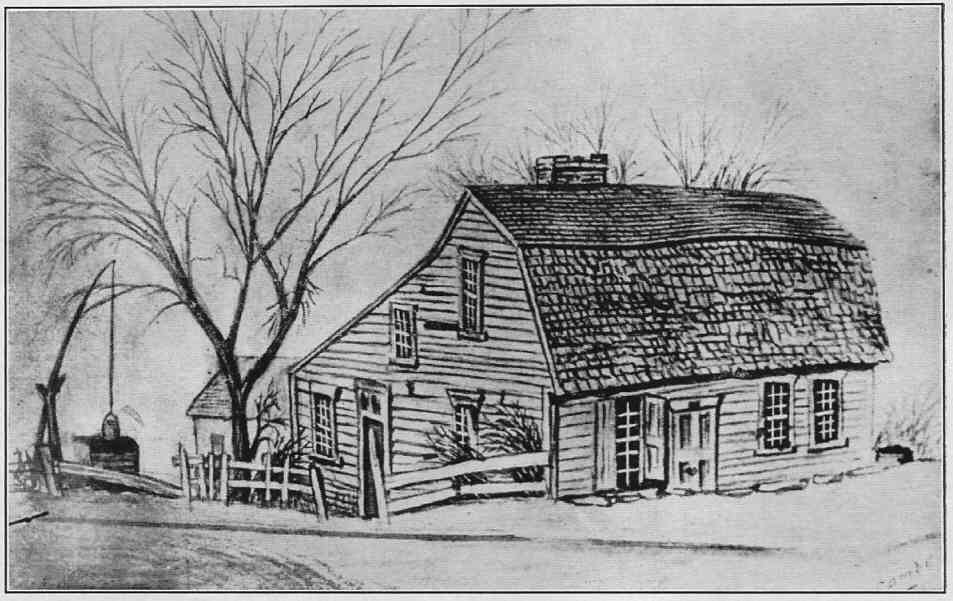

We may turn back to the story of Providence after the adoption of the first charter in 1647, when discussions around the ton-mill, where there was “a parliament in perpetual session,” were developing new communal life. The first houses about Roger Williams’ Spring and along the Towne Street without doubt were of logs halved together at the corners.1 Having only one room they were roofed over with logs or thatched on poles. The chimney was probably of logs, outside at the end and plastered with clay. The houses succeeding these log huts were similar—they being a single or “Fire Room.” One end was almost given up to the stone chimney and cavernous fireplace. These conclusions of Isham and Brown correspond with those of Mr. Dorr, though the architects investigated independently and by different methods.

There were no larger houses of the comfortable type introduced from Connecticut, as we have noted at Newport. Mr. Don found in the probate records that houses until the last decade of the seventeenth century had two apartments only, a “lower room” and a “chamber.” Often there were no stairs, and a ladder communicated. Most dwellings were destroyed in 1676 by the Indians, and the pioneer work of our plantation had to be repeated. One of the most interesting dwellings built about 1653 survived

|

1 Isham and Brown, “Early R. I. Houses,” p. 16. |

74

the ravage of King Philip’s War, and until our own time. It was known as the Roger Mowry house, or tavern, and recently as the Abbott house. It was a small building, and originally had a huge stone chimney. It was the first licensed tavern, where town meetings were held and the council assembled. Roger Williams gathered people there for worship.

To enter into this pioneer living we must remember that these planters made their habitations and the furniture chiefly with their own hands.2 They framed the solid chests and tables—rude but strong—which stood on the sanded floors. The clumsy but hospitable old English settle3 lifted its high back at the family table; then by the fireplace it afforded a room and partial exclusion from the fierce wintry drafts. In summer it was moved out of doors, and helped to make the evening cosy and agreeable. Regular chairs were a luxury—many having none, some possessing one or two. John Smith, the miller and town clerk, had four. The inventory of John Whipple, inn-keeper, recorded in 1685 “three chaires.” The way of living and the comforts were such as English yeomen of the period enjoyed. There was little table linen. The ancient wooden trencher held its place—little disputed by earthern ware or “puter.” Culinary utensils were limited, and the ancient iron pot served in many functions. No early inventories carried silver plate or carved furniture, as in Massachusetts; for Providence was striving hard to maintain life by agriculture alone.

Living was very simple, except when some large political

|

2 “R. I. Hist. T., No. 15,” Dorr, p. 28. 3 “It is, to the hearths of old-fashioned cavernous fireplaces, what the east belt of trees is to the exposed country estate, or the north wall to the garden. Outside the settle candles gutter, locks of hair wave, young women shiver, and old men sneeze. Inside is Paradise.” |

75

question involving colonial administration forced the little community to go beyond its own narrow affairs.

An ordinance4 in 1649 compelled every man to mend and make good the highway “before his house Lot or Lots.” Suits at law regulated differences, for the attorney’s fee for preparing a cause and pleading was fixed at 6s. 8d.; “if any man will have a lawyer he shall pay 1s.”

We have noted the secondary proprietors, who received a gift of twenty-five acres, and they are voted in from time to time. In 1650 it was enacted5 that in future all men received should pay for their “home-share 1s. per acre and 6d. per acre for the rest not exceeding twenty-five acres.” Outside their lots and farms, privilege of pasture on the common lands helped the semi-pastoral cultivation. Rates were 3d. for cows, 1d. for swine and 1d. for goats on the common, assessed in 1649, and collected by the town constable. There was much legislation concerning the commons, and in 1650, it was forbidden to take off lumber or timber. As the cattle ran in a common herd literally, marks identifying the ownership were quite important. These were formally enrolled on the records of the town. Many only cropped one ear in some way, but others introduced an elaborate device; as a crop from the top of the right ear, and a halfpenny behind under the ear. Another has a flower de luce on the left ear. The sale of liquors, to Indians especially, caused constant annoyance and tinkering of statutes. Entertainment of travelers and strangers seemed to be a burden requiring supervision, before taverns were regularly installed and maintained. An ordinance in 1650 allowed any one to sell “without doores”; but if “any man sell Wine or strong Liquors in his house, he shall also entertain strangers to bed and

|

4 “Early Rec.,” Vol. II., 44. 5 Ibid, p. 53. |

76

board.” Notice for sale ankers (10 galls.) liquors by sundry persons appear from 1656 to 1664. In all American hostelry, while the weary and hungry traveler might need rest and food, the necessary profit has come from the alcoholic thirst of the majority.

At the only town-meeting when Roger Williams appears as moderator June 24, 1655, the sale of wines or liquors to Indians was absolutely forbidden, under a penalty of six pounds, one half to the informer.

In 1657 Mr. ffenner was allowed by vote to exchange a six-acre lot at Notakonkanit bought of “Goodman lippet” for — acres. The distinctions Mr. occasionally old English Goodman and Yeoman frequently were used, but the differences marking the titles were not altogether clear.

In common names, English uses prevailed. As might be expected Gideon, Daniel, John, James, Simon, Zachariah; Mary, Rebecca, Esther, Ruth were frequent. A person might be denominated or designated by these familiar words, but the extraordinary fashion of the Puritans appeared occasionally. What conceit, fancy or ideal spelled out Mahershalalhashbaz? It might be considered unique, were it not recorded twice before 1680. A name preserved through many generations of honorable men, according to tradition, marks an event in colonial history. Richard Waterman set to keep the garrison at Warwick “firmly resolved” to hold out to the last. In reminiscence he named his son “Resolved.”6

The apprentice system was important in this period of colonial life. When unkindly fate had left lad or girl without parental care, he or she was bound out in order to learn. We shall note many interesting examples in the life at Portsmouth. In 1659 at Providence

|

6 Moses Brown MSS., “R. I. H. S.” |

77

William Field took in charge William Warner, who was bound “his Secretes to keep and not to frequent Taverns or Ale-Houses, except about my said master’s bussenes.” At the end of his subjection, he was to receive the customary freedom suit of clothing.

The community of interest and feeling which makes a state, appears to have been of slow growth, in our plantation of Providence. Clarke was not fully paid for his proper expenses. Roger Williams was obliged to berate the town they “ride securely by a new cable and ankor of Mr. Clarke’s procuring” and refused his just claims. In 1660 when the charter had been working a dozen years or more, a petition was sent to the commissioners at Portsmouth asking release from an assessment of £30 toward building a common prison at Newport, which “will be in no ways beneficiall to us.” Moreover, Providence was expending £160 for a bridge over the Moshassuck which was completed in 1662. The colony would not relieve the plantation from its proper burden and a tax for £35 was laid in 1661 to discharge the responsibility.

The community of the plantation at Providence grew out of the determination of Williams and his near associates to have absolute freedom of conscience. They must live, whether worshipping freely or under theocratic tyranny as they conceived it. Williams’ own views of practical government were simple and notably naïve, whenever he came into conflict with the proprietors. Without doubt, he had expected greater practical authority in the town than had fallen to him. He attempted in that time to assert political influence in a community which had no religious establishment. Mr. Dorr7 sagaciously points out that he expected substantial

|

7 “R. I. H. S.,” New Series, IV., p. 81. |

78

results without due causes. He forgot that a theocracy plants its feet on the earth and that the civil power made John Cotton the foremost man in Massachusetts. Yet Williams in inmost conviction, cared far more for the spiritual than for the material conditions of life. This appears in most striking form, as he writes his friend Major John Mason in Connecticut in 1670.8 Whatever might be his deficiency as statesman and executor of civil law, certainly the seer and prophet spoke in him.

A controversy in the turbulent winter 1654-1655 suggests much in the development of our early history. We should bear in mind that two main parties at this time were constantly struggling for control of the town meeting. One led by William Harris and Thomas Olney represented the Proprietors or original purchasers under Williams’ “Initial deed.” The other led by Roger Williams and Gregory Dexter generally consisted of small freeholders admitted afterward.9 All these men had resolute wills, while Harris and Olney had much executive ability. This difference began early, and for some two-score years, disputes growing out of these peculiar, differentiated land-titles convulsed the little plantation. Many small freeholders believed with Williams that the lands bought from the Indians were a virtual trust for the whole body of freemen. Proprietors on the contrary held that the lands were administered by the central authority in town meeting, for the benefit of private owners who had paid for them. The economic principle of ownership and the larger political motive involved in government, did not coincide in practical action.

Williams was never able to induce the town meeting to decide on any definite and particular sale of lands.

|

8 Ante, p. 9. 9 Cf. “R. I. H. S.,” New Series, Vol. III., Dorr, “Proprietors and Freeholders.” |

79

The Proprietors insisted on their view and they alone acted on such propositions. It appears from Williams’ own writings10 that the smaller freeholders came to Providence with no clear understanding of their relations to the first Proprietors. The “Initial deed” created no definite trust. Instead of such legal obligation, there was in Williams’ mind a moral duty—an inference. In the absence of coercive judicial power, this was “the weak point of all Williams’ machinery.”

The first organization of our Plantation in Providence —a voluntary association or “town fellowship,” without coercive force—was ill adapted for the political regulation of a community, in which there were many discontented people. The small freeholders were hazy about rights in public property and they fed their goats and swine on the common; taking thence, timber, firewood and other supplies. “Common” in Providence was not in the legal sense an “incorporeal right” of pasturage or other profit on land of another or of the town, but it meant unenclosed or nonimproved land claimed by the Proprietors.

There was a process of development going on step by step, as was indicated in the twenty-five-acre agreement of 1645. Then the pressure of Massachusetts and the fear of intervention on the part of England, warned both proprietors and freeholders that mutual concession must be made. Whatever the technical proprietary right might be, the sensible forecasting American saw that a monopoly could not avail, when the whole institution of property was supported only by voluntary association. The disputes tended toward settlement, by the creation of new classes of citizens, who, though they might be lower in property qualification, could vote if respectable.

|

10 Cf. Mr. Dorr. |

80

By 1649, there were oxen enough in use to compel the dwellers on Tone Streete to make a good highway before each estate. In the autumn of 1654 there was a tumult occasioned by a voluntary training. The record says Thomas Olney, John Field, William Harris and others were implicated. In the names reported, we see the proprietary party, striving for order according to their own notion. Those remonstrating against their action sent a paper to the town asserting “that it was blood-guiltiness and against the rule of the gospel, to execute judgment upon transgressors against the private or public weal.” This not only rebuked a particular executive act, but would have upset the authority of all civil society. These aberrations of his followers drew from Williams an expression which the learned and sedate Arnold well defines to be a “masterly” analysis of the limits of civil and religious freedom. It shows moreover that though executive facility might be lacking in Williams, the preacher and prophet yielded in him, to the greater powers of the civilized man.

11 This admirable statement sufficiently rebukes the main detractors of Williams. A society based on these divine principles, could never go far astray though it might indulge individual aberrations. A generation later, Cotton Mather busied himself in slurring Rhode Island for its many social defects. He wrote like one blind, who had never seen the light.

Reinforced by this moral support of Williams, the party in power—the proprietors—forebore wisely and condoned the civic offense. It was voted, “that for the Colony’s sake, who have since chosen Thomas Olney an assistant, and for the public union and peace’s sake, it (the tumult and disturbance) should be passed by, and no

|

11 Ante, p. 9. |

81

more mentioned.”12 Thus, the temperance and compromise of true politics worked itself out, among these hardy exponents of the human will.

The effect of such disputes on practical politics and daily living was shown in the matter of Henry Fowler’s marriage. For the greater part of the seventeenth century, there was so little religious organization that banns could not be published before a congregation.13 Accordingly, notice of this ceremony, so dear to all Anglo-Saxons, was literally civic, and was made to the town meeting, June 4, 1655.14 Fowler was warned to the Court to answer for his marriage without due publication. He answered that, “the divisions of the town were the cause,” and the town remitted the penalty. Mr. Don considers this a “bold and successful answer.”

As bearing on industries we may observe that Thomas Olney, Jr.,15 was granted a house lot in 1655 “by the Stampers” provided he would “follow tanning.” This lot gave water power which was not all used until sixty years later in 1705.

There was constant difficulty through sincere effort to reconcile communistic (in our phrase) desires with proprietary rights in the growing settlement. We may well study the meager records of divisions of land, so far as we can. We remember16 that in 1645, twenty-five-acre or quarter-right purchasers were admitted to “equal fellowship of vote” with the first purchasers. This class received in every division of land one-quarter part as

|

12 Staples, “Annals,” p. 113. 13 Marriage was legally a civil contract throughout New England. Generally the statutes required the banns to be published at two town meetings. 14 Early Rec. Prov., Vol. II., p. 81. 15 Dorr, “Planting and Growth,” p. 50. 16 Cf. Ante, p. 37. |

82

much as a full purchaser. The number of purchasers of both kinds never exceeded 101 persons. They were admitted at various times on various terms; the date of the last admission cannot be determined. March 14, 1661-2, an act17 was passed to divide the lands “without the seaven mile line.” In this outside division the “twenty-five-acre men” were allowed each “a quarter part so much as a purchaser,” paying one-quarter of the charge for confirmation. The right arose from “commoning within the seven mile bounds,” only those having full right of commoning within, being equal to a purchaser. The grant was allowed on condition that each should break up one-half acre of “his home lot before next May 12 mos.”

The communistic sentiment noted in the original allotment, was manifest in various movements for democratic equality. The home-lot of five acres, the distant meadow or six-acre lot, the “stated common lot,” together with land-dividends among the proprietors, all resulted in numerous small estates, widely separated. Economically, the yield was not equal to that of the Pawtuxet settlement, where the methods were more like those of ordinary pioneers. Pawtuxet for the first eighty years, paid nearly as much tax as the much larger Providence. And the effect on the future development of the plantation was more important and far reaching. While the elaborate system of home-lots created strong local attachment it cultivated prejudice as well. All the limitations of farming life, extended into, warped and biassed a community, which should have grown into a commercial center two generations before it actually did. The proprietors clung to every habit and privilege, driving the settlement outward and westward, as the

|

17 “Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. III., 19. |

83

expanding commercial life compelled progress of some sort.

Let us remember that, then nowhere in the world perhaps were the two greatest motives affecting human society at work so freely and practically as in the little colony and especially in the plantation at Providence. Freedom of conscience and desire for land animated the settlers there, and often struggled for mastery. The individual sacrifices of Williams, Gorton and the Quakers for soul-liberty are well known.

Religious organization among the planters at Providence had little influence until commerce had fairly begun in the eighteenth century. Politically the associated religionists acted in the town meeting as proprietors or freeholders. There was nothing like the direct influence of a Puritan congregation, or its indirect movement, in what we call public opinion. About twelve families sympathized with Williams in forming the early Baptist society, but the majority refrained from all religious association. William Harris, after Williams the most influential citizen, belonged to no religious body after seceding from the Baptists. Williams kept on with the Baptists only about three months, and was known as a “Seeker.” Mr. Dorr, a conservative churchman, severely criticised all these movements, but we must consider his facts.18 He said the worshipers of Liberty had some noisy declaimers like Hugh Bewett, and some political agitators like Gregory Dexter who were revolutionary in England. There were two Baptist churches in Providence as early as 1652;19 one of the six and the other of the five principle Baptists. The First Church kept its continuous life. It differed from the communion in Newport.

|

18 “R. I. H. S.,” New Series, Vol. III., 204. 19 Staples, “Annals,” p. 410. |

84

July 10, 1681, the record20 is preserved of a long disputation based on scriptural texts between Pardon Tillinghast, Gregory Dexter and Aaron Dexter of Providence and Obadiah Holmes of Newport. Providence contended, whether “repenting believing Baptized Disciples are visible members of Christ’s body and have right to Fellowship breaking of bread and prayer, we deny according to our understanding of your sense.”

Political force as embodied in citizens, is necessarily wiser and more enlightened than the mere grasp of a land-holder. It was obliged to recognize that man as well as property must join in making a state, and that actual freemen must be encouraged. At an early (unknown) date, the suffrage had been restricted to married men. The young men—probably then in the majority—were discontented under the restriction for nine years. In the fifties it was decreed that “all inhabitants not as yet accounted freemen should be liable to do service not only military but mending roads and like hard work.” In the mid-century, the plantation had three distinct classes of voters not sympathizing,21 proprietors, quarter-rights men, and small freeholders at large. These divisions not only marked estates, but social distinction and privilege as well. The newest freeholders were smallest in estate and least in political influence. Meetings sometimes included proprietors in the same persons. In later days, only proprietors could vote on questions involving “common lands.”

Inevitably there was political agitation and social friction between these varied and variable persons seeking liberty and the practical privileges of freemen. Each home-circle was a debating school where talk served instead

|

20 Moses Brown MSS., Vol. XVIII, p. 247, R. I. H. S. 21 Staples, p. 218. |

85

of books to draw out the mind. As an ample fire roared in the massive chimney, or a blazing pine knot lighted the eager faces, all contemporary history, all theology in fixed fate or foreknowledge absolute, was discussed by these new Americans. But at the town mill these educated wranglers met in more serious controversy. The intense English ambition for possessing land, the political passion of a freeman, were here exercised in exciting discussions. Sometimes opinion degenerated into license, as we have noted at the training in autumn 1654. But generally questions were threshed out in these wholesome if exciting discussions, and were decided in some fashion at the turbulent town meeting.

Manners as well as morals and statutes were matter of lively interest. The natural man was disciplined in some way, and reduced into new forms of social order. To wit “that they that whisper or disturb ye Court or useth nipping terms, shall forfeit six pence for every fault.” More strenuous was it, when if “any man shall strike another person in ye Court, he shall either be fined ten pounds or whipt.”

We cannot repeat too often, nor mark too forcibly, these new and complex modes for educating and evolving a citizen; for forging out a working member of the body politic. All these moral and political influences acting on the first generations of planters, positively affected their descendants. State heredity is even more powerful than individual descent. Roger Williams, Gorton, George Fox, Coddington and William Harris in the seventeenth century, issued in Stephen Hopkins of the eighteenth, and Thomas W. Don, of the nineteenth. The latter, a conscientious patriot in theory, in practice became a civic rebel.

The pregnant disputes between proprietors and freeholders

86

were gradually wearing out and a final process of economic adjustment prevailed over the crude communistic theories, which had vexed the life of the early plantation. The date is not positive, but about 1665.22 A town ordinance laid out a four-mile line within the old seven-mile line. A second or “50 acre division was made by lot to every ’purchaser.’” Lime rock was to be left in common. As usual, discussion outside had prepared the voters for these propositions. The result in town meeting was concord and not the strife of old time. The day arrived, with no lack of quorum at the inn, where the freemen assembled; while intense curiosity preserved order. Before formalities began “arose the gaunt and picturesque figure of the founder.” Williams’ stock arguments against the “usurpation of the proprietors” would not hold now, for he was partaking as a “purchaser.” He “witnessed” against the “prophaning of God’s worship by casting lots.” The stalwart prophet had nothing more to say of “up streams without limits” or of the “fellowship of vote.”

We may note a very interesting episode in crude law-making. May 27, 1667,23 in town meeting a will was made for Nicholas Power, who died intestate some ten years earlier. Endeavors had been made meanwhile to settle the estate under the general laws of the colony; but the widow would not consent and the council had not power to compel her. At last a will was made as above stated. As Judge Staples24 remarks, where the power was obtained, does not appear, but it was exercised repeatedly, not only in Providence, but in other towns,

|

22 “Early Rec.,” Vol. III., 93. 23 Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. I., 31. 24 “Annals,” p. 124. |

87

”Wills so made were not simply divisions and distribution of the intestates’ estate among heirs, but in some instances specific bequests and devises were made, and estates for life, in tail and fee created, as the council supposed the interests of all concerned required.” This practice continued into the nineteenth century in the smaller towns. It was a return to social ethics, when the law for individuals failed to award justice. It served the time well, and was almost never abused.

Staples25 cites in 1662 a privilege given one Hackleton to burn lime, from stone taken from the commons, as the earliest notice of that manufacture. The kiln was near Scoakequanoisett. All lime rock was for some years kept in common, but was ultimately conveyed with the lands. Mr. Bowditch thinks lime from shells or probably from stone was made as early as 1648. There was little lime produced until brick building was introduced a half century later. Probably the earliest list of tools belonged to John Clausen, a Dutch carpenter, about 1660.26 Froe, bench hook hammer, 1½ × 1 inch augers, narrow axe, hallowing plane, cleaving and moulding do, three other sorts, chizells, gouge, three Brest wimble bitts, a joynter plane. This list shows the condition of carpentry. Wm. Carpenter, an English-bred carpenter, came from Amesbury and built a house for Wm. Harris before 1671 (probably).

The authority of the crown was demonstrated for the first time, by the visit in 1665 of a royal commission—Nicolls, Cartwright and others. The commissioners met a better reception than in Massachusetts, and their proposals for the general guidance of the General Assembly

|

25 Staples, “Annals,” p. 613. 26 Field, “Providence,” Vol. III., 583. |

88

were promptly accepted, as being “in perfect unison with the principles of Rhode Island.”27

Much controversy with Connecticut for possession of the Narragansett country, vexed the colony for several years. Connecticut was favored by some of the local residents about Wickford and incidentally by William Harris. He offended his own colony so much by this action that he was imprisoned at Newport and not allowed bail. He was finally released and restored to office, when the Quakers controlled the politics of the colony in 1672.

An indication and permanent sign of progress in the plantation was in the erection of Weybosset Bridge in 1672. This was a great effort for the little community. Expedients for a bridge had been maintained by tolls from strangers and contributory work from townsmen; one day’s work of man and team per year, for each family. Roger Williams showed his customary public spirit,28 by assuming the burden of the bridge under these conditions in 1667-8. A committee had previously failed in getting support to care for the bridge.

After Williams and Gorton, the most positive and formative influence in early Rhode Island, was the society of Friends. The “cruel and sanguinary laws” of Massachusetts drove out these pilgrims—harmless in our view—and they flocked into Newport. Here they found a free atmosphere and many people with minds open for the reception of their ideas. In England, the seventeenth century had gathered from Geneva and Holland the most illuminating as well as the most vague doctrines of the Protestant faith. Anabaptist and Antinomian—though frequently used—were vituperative names, rather than

|

27 Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 113. 28 Staples, “Annals,” p. 144. |

89

terms philosophical and descriptive. In England and America, these floating doctrines were best represented by the society of Seekers with which Roger Williams finally associated himself. But Williams never could formulate his own large conceptions into dogmas capable of founding solid societies.

These elevated incorporeal ideas possessing the individual soul were gradually concentrated in the “inner light” of George Fox. This asserted a constant communion of the spirit with its creator—moving independent of all constraint and of all ecclesiastical control. That mere crotchets should incumber these true spiritual conceptions was inevitable. But notwithstanding some individual vagaries, the Friends or Quakers as then called were an immense influence for good, and especially in our colony. As above indicated in treating of education,29 the Friends self-regulated in themselves were especially beneficent in a self-governed community that lacked self-control.

At Newport, the seed sown by Anne Hutchinson had prepared ample growths for the Quaker propaganda. In the course of development the Baptist church had been separated, a part holding to regular ordinances under John Clarke, and others like Coddington and Easton adopting Quaker tenets. The great apostle of the “inner light,” George Fox, visited there in 1672, and was the guest of Governor Easton. For the reasons stated, he found himself quite at home and the “people flocked in from all parts of the island.” When he came to consider Providence, though it had no established church and no hierarchy, he soon discovered theological wheels within wheels, and that every man his own priest may become a very priestly factor. On his visit there

|

29 Ante, p. 68. |

90

the reformer said the people “were generally above the priests in high notions.” They came to his meeting to dispute and, in his own words, he was “exceeding hot, and in a great sweat. But all was well, the disputers were silent, and the meeting, quiet.”30 The silence could not last long, for the storm was gathering. Williams challenged Fox on fourteen points of doctrine; seven to be publicly discussed in Newport and seven in Providence. Williams rowed himself to Newport in one day—a wonderful feat for a man over seventy. Fox had departed, but his followers debated with Williams for three days and then concluded at Providence. The result was an easy victory for each, in the opinion of both. Williams summed up in a volume, whose title “George Fox digged out of his Burrowes” shows the cheap controversial wit of the time. For with his disciple Burnyeat replied in “A New England Firebrand Quenched.”

The arguments and figures of rhetoric stand to this day, but the propaganda then went with the Quakers. Men like William Harris in Providence took up the doctrines. A week-day meeting was established in Providence in March, 1701, and a “fair large meeting house was built in 1704.”31 From 1672 to 1676, the colonial politics were controlled by the Friends, and it was mainly due to their non-combative policy that the colony was so poorly prepared to meet King Philip’s War.

In 1665, the controversy began in 1657,32 between William Harris and the party of freeholders was much aggravated, and it lasted until his death in 1681, at times convulsing the whole colony.33 As has been noted,34

|

30 Brigham, “R. I.,” p. 117. 31 Staples, “Annals,” pp. 423, 424. 32 Staples, “Annals,” p. 118. 33 Brigham, pp. 113-116. 34 Ante, p. 79. |

91

the Proprietors and Freeholders were generally at variance, but these contests involved great personal bitterness as well as self-interest.

William Harris with his brother Thomas came in the ship Lyon. According to tradition, the family were “harsh and irregular of feature, brawny, resentful and pertinacious in temperament, and, in speech rasping.” Harris’ own writing is preserved; it is most individual, thoroughly his own and is even more difficult of interpretation than the ordinary chirography of the seventeenth century. It is thoroughly elegant, as would hardly be expected from the above rendering of the family traits.35 Like many strong men of his time, he was educated by affairs and not by the schools, had great facility in business and a fair knowledge of English statute law. His books36 were few but useful; bibles, concordance, dictionary, surveyors learning and legal treatises including Coke on Lyttleton, medical treatises, several on “faith,” “nature’s Explecation,” “the effect of war,” “contemplation moral and devine.” Evidently this was a collection much used by a busy man of affairs who thought for himself.

The main contention of Harris was that the “initial deed” in its clause “up the stream of Patuxet and Patuckett without limits we might have for our use of cattle” gave not only a right of pasturage, but the land in fee simple. To further this the contestants bought “confirmation deeds” both for lands and rights of pasturage of the degenerate sachems coming after

|

35 “He brought to whatever he undertook the resources of a great mind and, to all appearance, the honest convictions of an earnest soul. On this account he was a more dangerous opponent and required stringent measures to suppress the errors of his political creed.”—Arnold, Vol. I., 262 36 “Early Rec. Prov.” Vol. VI., p. 75. |

92

Canonicus and Miantinomi, extending twenty miles westward from Fox’s hill. Roger Williams always solemnly protested that possession of the land was never intended by the great sachems in the conveyance for the “use of cattle.” This seems reasonable either in the seventeenth or twentieth century.

In 1667, the quarrel broke out anew in the town meeting, the factions being led by William Harris and Arthur Fenner. The two parties chose contesting delegates to the General Assembly. If our forefathers had not reporters and newspapers, they revelled in pamphlets, fiercely polemical. The Fenner party issued a most bitter one, “The Firebrand Discovered.”37 This fiery distinction was a customary title, eminent, but not honorary conferred on William Harris. As this contestant was strong in law as well as in language, he induced the Governor to call

|

37 We may cite a few sentences from this dissertation, written by Williams doubtless, for they correspond with his statements in “George Fox digged out of his burrowes.” These phrases show the way of thinking and method of expression among neighbors in the Plantation, “ffirst his nature, he is like the salamander always delighting to live in ye fire of contention. 2, his nature qualities and conditions doth further appeare, he is a Quarilsome man (beat Adam Goodwin, an officer). 3, he is like the raging sea casting forth mire and dirt. Men of high degree or lowe degree; he casth on them foole, knave, base fellowe, scounderill or the like. 6, you question with ahasuerus who is he, we answer with Queen Esther, the enemie (Esther, VII., 5-6). The firebrand is this wicked Harris, commonly called Mr. William Harris.”—R. I. H. S. Col, Vol. 10, p. 78. In this Pawtuxet controversy involving Proprietors’ interests, a whole literature was developed. In 1669 Harris took part by protesting against a paper presented by Gregory Dexter “an instrument and a soveren plaister or against our Rights in lands, lawn, ye Common law, statut law of England, and our rights in Magna Charta soe soundly confirmed by 32 parliaments. . . . I not only take myself bound to protest against ye said poysonous plaster but also to complayne of Gregory Dexter for his notoryous crime against ye King’s law and peace.”—“Mr. Harris.”—Ibid, pp. 93, 94. |

93

a special session of the General Assembly, which was the court also, and lodged a suit against his opposers. But the legislative and judicial petard gave him a sorry “hoist”; for the tribunal chose Fenner’s delegates from Providence, cleared the charges against him, and discharged Harris from the office of assistant. In addition, on petition of the town of Warwick, the assembly fined Harris £50. for imposing an extra session on the colony in the busy season of the year. Harris was chief of the committee to collect from the colony the tax to pay John Clarke’s expenses in England, while procuring the charter, and had made himself especially obnoxious to Warwick.

The town of Warwick was particularly delinquent in this affair; one of the most discreditable episodes in our colonial history.38 Doctor John Clarke’s expenses in England, while procuring the royal charter, the secured foundation of the colony, had been slowly paid and never were fully liquidated. Yet no one deserved more from the planters than this esterprising, wise and forecasting statesman. Roger Williams berated Providence that, they “ride securely by a new Cable and Ankor of Mr. Clarke’s procuring” and refused his first just claims. He wrote Warwick a letter, powerful and befitting in our view,39 but “pernitious” in the view of the town, who protested against it unanimously. Warwick had some reasons for objecting to its proportion of the tax. But these reasons did not prevail with the General Assembly, which ordered a letter “to provoke and stirr them up to pay.” This caused some noteworthy proceedings—curious even for Rhode Island. Warwick considered a letter from the committee on tax in 1669 “as if it had

|

38 Durfee, “Judicial History R. I.,” p. 124. 39 “R. I. H. S. Pub.,” Vol. VIII., 147. |

94

been indicted in hell.” Unanimously the town ordered the “Clarke to put it on a file where impertinent papers shall be kept for the future; to the end that those persons who have not learned in the school of good manners how to speak to men in the language of sobriety (if they be sought for) may be there found?40 This sublime courtesy from a debtor who was arraigned “out of hell” might have graced a Chesterfield. This “impertinent file” became a customary parliamentary instrument. That it was lost, is a misfortune; for its peremptory and excellent system of classification might have enlightened these modern times. In another connection this remarkable instrument appears as “the dam-file.”

The disputes of Warwick with the colony were contingent to the constant controversy of Wm. Harris against Williams and his associates. Harris availed of every circumstance to push his own polemics. Now in 1672, he became the ally of Connecticut41 in her attempts to get possession of the Narragansett country. The planters there inclined toward the movement of Connecticut. The government of the colony was changed on this issue, the moderate Quakers joining with the Narragansett planters who favored Connecticut; Easton becoming Governor in place of Arnold. But subsequently the people checked this unwise movement, and repelled the action of Connecticut. Harris was styled “traitor” and imprisoned by his opponents, after the controversial methods of the time; but he hardly committed overt treason. These transactions in town and assembly meetings seem very petty now. We are to remember that, not only was the citizen uneducated in the modern political sense, but he had much to unlearn that had been

|

40 Arnold, I., 336n. 41 Brigham, p. 121. |

95

forced into him by feudal usurpation and ecclesiastical oppression. The democrat was coming to his own through all sorts of vagaries. The process was petty and defaced the body politic on many occasions, but it formed a practical working democracy.

We should notice the social function of the colonial tavern, everywhere necessary and nowhere more important than in the little community at Providence. The intense individuality of the planter must have some social vent and opportunity for expression. The modern club, caucus and festive church meeting were anticipated mostly in the taverns of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The first inn in the colony was licensed to William Baulston at Portsmouth in 1638.2 In March, 1655-6, the colony passed an ordinance, closing bars at nine o’clock. But the Assembly probably found that taverns were better regulated by local authority, for in 1686 all laws relating to excise on liquors, keeping taverns and selling arms to Indians were repealed.

Gatherings at the town mill and later at the better taverns afforded a constant round of discussion and gave play to social excitement. A very curious sidelight is thrown on Providence society by a town ordinance in 1679. The religious excommunication of Rhode Island imposed by the other colonies of New England was so severe that the planters were often impelled to impose ordinance and law to maintain public decorum. Others thought so ill of our colonists it was necessary to show that they thought well of themselves. This act enjoined employment of servants for labor on the first day of the week; all sporting, gaming or shooting was likewise forbidden—simple and proper, civic regulation. But for

|

42 Arnold, Vol. I., p. 129. |

96

taverns all tippling was suppressed on the Sabbath “more than necessity requireth.” We may readily imagine that a fierce discussion on proprietary rights or an evolution of Calvin’s institutes might produce a stomach ache requiring necessary flip or toddy.

The acrimony of the town meeting was lighted up by an occasional joke. Regulating the Common lands was a constant annoyance. Pigs especially disturbed the over-burdened administration. In debating an ordinance to fence them out, Wm. Harris said, “I hope you may goe looke as Scoggine did for ye haare.”43 Scogan’s Jest Book was one of the most popular chap-books in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The regulation of traffic in liquors was a constant source of trouble. An act July 3, 1663,44 declared some sellers to be so “wicked and notorious as to deserve to be Branded with the name of Jaackes Cleansers.” Circumstantial evidence and the testimony of Indians have always troubled jurists. In these cases the planters made one positive good out of two possible evils. For it was provided at this time that the testimony of “an Indian, circumstances agreeing with such testimony” should convict under the ordinance of 1659.

In 1675 and the year following, Rhode Island was shaken to its foundations and the plantation of Moshassuck at Providence was destroyed for the time. The concentrated Indian uprising known as King Philip’s war, greatly injured Massachusetts and Rhode Island, while it ruined the native Indians. There were grievances on both sides, as always when barbarism encounters civilization. Philip and Canonchet in no wise equalled old Canonicus, one of the greatest North American aborigines.

|

43 “R. I. H. S. Col.,” Vol. X., p. 75. 44 “Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. III., p. 38. |

97

We shall never know what might have occurred in the thirties, had the Indians resisted the English outright; but in the seventies to hurl savages against the solid growth of English civilization as Philip did, was simple madness. These desperate contests have been amply recorded and we may only refer to the voluminous history. Ellis and Morris45 have shown that the slaughter of the Narragansetts at the swamp fight was not as complete as was formerly imagined; but the impairment of the nation caused by the whole war was thorough. Scanty remnants finally settled in Charlestown, leaving the rich territory of aboriginal thousands. The mainland, about and through which the Indians lived, was a very theater of war. The power of government and administration of affairs was on the island controlled by the Quakers, and it was five times as wealthy as the other plantations. Whatever place—and it should be a very worthy place—we may assign the Quakers, in the building of individual character and in religious development, their function and their doings in political government have brought failure, wherever their principles have been enforced. According to Richard Smith, a prominent settler in Narragansett, “the Governor of Rhode Island being a Quaker, thought it perhaps not lawful either to give commission or to take up arms; so that their towns, goods, corn, cattle were by the savage natives burned and destroyed.”46 Governor Coddington was old and the ruling citizens comfortable, quite willing to rest and be thankful. Moderate garrisons would have saved Providence, Warwick and outlying Narragansett, but the mainland was left to sorry fate.47 Narragansett and Pawtuxet were cleared;

|

45 King Philip’s War. 46 “R. I. C. R.,” Vol. III., p. 51. 47 Brigham, pp. 125-129. |

98

Warwick kept one house, while Providence had not above three.48

The wretched and monotonous litigation over proprietary rights and disputing plantations was not lessened by conflicting titles, left by the devastation of fire. Wrangling disputes over rights to the land continued to vex the community for some ten years.

“Whatever may have been their motive in deserting the mainland towns—whether it was political enmity, Quaker antipathy against war in general, or a selfish desire to preserve their homes—such action did much to foster an alienation between the mainland and the Island which hindered a united colony growth for many years.”49 In 1676 died John Clarke, scholar, physician, minister and statesman; above all a pure patriot. Al-ways in public affairs, his “blameless self-sacrificing life” left him without an enemy, although in these times strife everywhere prevailed.

Woman, the true helpmate of those days, was not in the best position when she was “unattached.” The maiden, the unmarried female or spinster, was not in the best circumstances when she did not spin at her own wheel. The wills show many curious arrangements, where the maidens were controlled by a rigid family discipline.

|

48 Rates assessed in 1678 show the relative conditions of the towns. Newport £136, Plymouth £68, New Shoreham and Jamestown each £29, Providence £10, Warwick and Kingston each £8, East Greenwich and Westerly each £2. A flotilla of sloops and boats was employed by the General Assembly to sail around the Island and defend it. “This is the first instance in the history of the Colonies where a naval armament was relied upon for defence. It was the germ of a future Rhode Island squadron, one century later, and of an ultimate American navy.”—Arnold, Vol. I., p. 409. 49 Brigham, p. 127. |

99

Zachary Roades, in 1662,50 able to give his daughters handsome legacies for the time, bound the will of the spinsters in summary fashion. To his eldest daughter Elizabeth he gave £80 at 21 years, or at marriage. To Mary and Rebecca £60 each on same conditions. But, if either “shall Marry or match themselves with any Contrary to ye Mind of their mother or of my two overseers (executors), then it shall be in their Mother’s what to give them, whether any thing or No.” Independent but not free spinsters; if concord followed there must have been some forbearance among those many wills.

Sometimes consent of parents was advertised in the notice of banns. Feb. 1, 1680,51 it comes from another colony, “I, John Wooddin of beverly in the covnty of essexe in New England doe not see now anything but that lawrence clinton and my daughter may proceed in the honorable state of matrimony,” cited from the “second publishing.”

The hardest municipal task—beyond early theological differences or proprietors’ disputes for lands—was in the control of sexual immorality. Persons offending in one town were handed over to the next en route. June 17, 1682,52 Ephraim Prey and Elizabeth Hoyden of Braintree were caught in flagrante delictu. The father of the girl agreed to remove her with Prey to his home in Braintree by June 22, at sunset, or both culprits would have been delivered to the next constable (at Rehoboth) “to be Conveid to their dwellings.”

In some cases, proceedings were very dilatory. Richard Bates53 appears April 25, 1683, having “a woman

|

50 “Early Records Prov.,” Vol. IV., p. 80. 51 Ibid., Vol. VI., p. 27. 52 Ibid., p. 43. 53 Ibid., pp. 100, 107, 113. |

100

abideing with you” and both were ordered off July 25. With his “pretended wife” he was questioned for contempt and obtained a stay of execution until Oct. 21. In December he was granted further courtesy until March 31. We can only suppose that the facts were not positively as bad as the judgments specify. Meanwhile the offenders must have gained some kind of better recognition from the neighbors, or this lax procedure would not have been allowed.

Mary Bellowes having come into town with a young child and “no bond for town’s security,” was ordered off in four weeks. This sentence was afterward extended about 8 months, July 12, 1683. Abigall Sibley,54 with her child, was ordered off. Thomas Cooper published his intention of marriage with Abigall, which was forbidden, because he had “manifested himself a person infamous in that he hath forsaken a sober woman, who is his wife.” Mistress Abigall, with her child, appears again, Dec. 13, “entertained by Thomas Cooper.” Her time of removal was extended to the first Monday in March, “not to live with Thomas Cooper” meanwhile.

Mr. Dorr notes the increase of creature comforts after King Philip’s War. Kitchen utensils and other improvements in the household showed more abundance. Frying pans, gridirons, spits and skillets manifested the departure from the boiling pot, and to some housewives these utensils appeared to be extravagant. Abigail Dexter, administratrix, valued in 1679, “a frying pan, a skillet and other trumpery,” at 10s.

There were few candles to burn, some of them being made of bayberry tallow. In 1681 the town-meeting forbade making tar from pitchwood beyond ten gallons per man for his own use on his own land. Pitchwood was “a

|

54 “Early Records Prov.,” Vol. IV., pp. 109, 114. |

101

great benefit for candle light “As naval stores were then greatly desiderated in all countries; this shows how little the agriculturists appreciated the commercial possibilities of their own land.

Tobacco was generally raised by the farmers and appeared upon the inventories in small quantities. Mostly for domestic use, in some instances it was gathered for export. Ephraim Carpenter, probably a small shopkeeper, had in 1698, 313 lbs. at 3d. £3. 18. 3. In “cotten wooll,” which was always coming from the West Indies, he had a value of 3s. 6d. Flax was grown as table linen became a necessary comfort. Linen-wheels for spinning were common.

Mr. Dorr notes that long after King Philip’s War there were meetings of the town held under the buttonwood tree opposite Crawford Street.55

We may note rates of taxation and prices of commodities. In 1663,56 £36 was levied toward the expenses of John Clarke, while procuring the charter in England. Pork was received at 28s. per cwt.; wheat at 4s. 6 per bu.; peas at 3s. 6; butter at 6d per lb. In 1664,57 the rate was £130, levied according to the apportionment of the General Assembly. Wheat and peas were unchanged and pork was at £3.10 per bbl. Horses and cattle were received at prices equivalent.

In 1678-958 for a rate of £20, the prices were for oxen £4; cows and 3 yrs. old, £3; horses and mares, 4 yrs. old, £3; swine, 15s.; sheep above 1 yr., 4s. Improved planting land was at £3 per acre and vacant land not improved 3s. per acre. Mr. Richman59 records the positive fall in

|

55 “Planting and Growth,” p. 94. 56 “Early Records Prov.,” Vol. III., p. 91. 57 Ibid, p. 58. 58 Ibid, Vol. VIII., p. 41. 59 “R. I.—Its Making,” p. 537. |

102

prices of food from 1676 to 1686, after the ravages of King Philip’s War had passed away. Good pork was at £2.10 per bbl.; good beef, 12s. per cwt.; peas, always a staple, 2s.6. per bu.; wool, 12d. to 6d.; butter, 5d. to 6d. The abundance of other articles shows agricultural increase, and the relatively small decline in butter indicates a demand produced by more comfortable living.

Sept. 1, 1867,60 the rate was £33.9.6. Silas and Benjamin Carpenter jointly paying £1.3 and Stephen Arnold £1.1.10, the highest individual taxes. Oct. 31, 1687, for another rate of £16.12.2. Indian corn was taken at 2s. per bu.; rye, 2s. 8; beef at three halfpence per pound; pork, 2d.; butter, 6d. For the rate of £37.12.3 in August, 1688,61 apparently they had rated more persons or had increased the portions of the majority, for Silas and Benjamin Carpenter stand at 16s.9 and Stephen Arnold at 17s.6; these magnates being reduced.

The disputes about land titles between Providence and Pawtuxet62 complicated the struggles of Proprietors and Freeholders, besides creating every possible difference among the direct contestants. Suit and cross suit, writ of ejectment with timid ineffective service, embarrassed these times and convulsed the community. The vigorous William Harris generally got his verdict, but failed in obtaining practical execution from the feeble administrators of law. This shows that public sentiment leaned against him.

We ought to look into the “Plea of the Patuxet Purchasers,” before the King’s Commissioners, Nov. 17, 1677.63 This whole document illustrates the curious

|

60 “E. R. Prov.,” Vol. XVII., p. 103. 61 Ibid., p. 12. 62 Arnold, Vol. I., p. 432-438. 63 “R. I. H. S. Pub.,” Vol. I., 185 et seq. |

qz

103

compound of English law and judaic interpretation which prevailed in the mind of New England . . . “The said discomposed Soules that so Object, do not believe such a bound. If any, my Charity toward them, as to their Actions or wisdom not being so simple in doing as Saying.” The essential argument is given in summing up. “That the words (might have for our use of cattle) doth give a property in a sound sense by words of Scripture 35 of Numbers and 3d verse, ’And the City’s shall they (have) to dwell in and the suburbs of them shall be for their Cattle.’ Verse 3d.”64 This was the outcome of the simple privilege “up streams for cattle” given by Canonicus to Roger Williams.

But in this fishing upstream for land, both parties went into muddy waters according to Mr. Richman. By “erratic and erring process in the field” seeking “where is the head of the Wanasquatucket,” Roger Williams and Arthur Fenner in 1678 surpassed William Harris “that master of tergiversation at his own game.”65

At Christmas in 1679, Harris, in pursuit of “more specific execution,” went to England for the fourth time. On his passage he was taken by Algerine corsairs, who were even more ferocious than the Christians of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the summer of 1681, he was ransomed, released and went to London, where he died in three days from debility induced by his captivity. The ransom was mainly paid by the colony of Connecticut, for which he was acting abroad in the disputed Narragansett boundary. The ransom was afterward repaid by his family. In 1680 he wrote, “Deare wife and Children let us Cast our Care on god without distracting feare, thouh I should here dy yet god lives, and I am not

|

64 R. I. H. S. Pub.,” Vol. I., p. 211. 65 R. I. H. S. Col.,” Vol. X., p. 19. |

104

without hope but that I may see you againe, let us pray fervently and Continually to god that is able to deliver and soe I commend you all to god all way.”66

Could there be a more pathetic situation? Bad, as were the greedy claims and angry quarrels of Pawtuxet and Providence—the barbaric Saracen was worse. And the fierce individual contestant out of this turbulent colony, was nevertheless in his heart the gentle Christian father commending all to his heavenly Father in pure faith.

Mr. Richman67 has studied the Harris and Williams controversy in every detail and probably knows more about it than any one. He is severe in his view of Harris. Let us quote the words of Arnold, whose judgment cannot be neglected, “Thus perished one of the strong men of Rhode Island. He filled a large space in the early history of the Colony, as an active, determined man, resolute in mind and vigorous in body, delighting in conflict, bold in his views of the political dogmas of his time, fearless in his mode of expressing them, striking always firmly, and often rashly, for what he believed to be the right. His controversy with Roger Williams was never forgotten, and scarcely forgiven, by either of these great men, and presents the darkest blot that rests upon their characters.”68

Mr. Dorr’s general view of these differences and conflicts is just; for the system was more at fault than the men. Lack of legal knowledge, still greater lack of judicial organization and executive power, inevitable in a

|

66 “R. I. H. S. Col.,” Vol. X., p. 321. 67 Cf. “R. I. H. S. Col.,” Vol. X., pp. 11-127, for hls study with original documents. 68 Arnold, Vol. I., p. 437. |

105

colony forced by circumstances into irregular existence; noble motives struggling with ordinary greed and necessity of living—all these compelling forces produced the disputes of Providence Plantation, too often ending in a quarrel.69 But let us not dwell on these minor shadows. These individuals were great as a whole, if faulty in detail, and they wrought even better than they knew. While recognizing the smaller defects, let us cherish the grand result.

In the years 1677 and 1678—contemporary with the withdrawal of Harris—there occurred the deaths of three most prominent citizens. Samuel Gorton,70 one of the most remarkable “men that ever lived,” passed away. With the vision of a seer, his mental astuteness, his scriptural learning, his deep reverence for established law, made of him an extraordinary conserving radical.

Quite unlike was Governor Benedict Arnold, who had lived at Newport twenty-five years, removing there from Providence. He was not moved by the arguments of George Fox and followed John Clarke politically, opposing the usurpation of Coddington. President of the colony under the patent, he was named governor in the second charter, and was elected by the people seven times. The confidence of his constituents proves his integrity and political sagacity. One act alone—his reply to the inhuman and arrogant demand of the United Colonies, for

|

69 Cf. Chief Justice Thomas Durfee, “Judicial History,” p. 18. The influence of Newport in the early history of the State has not been appreciated. The rest of the colony was very heterogeneous, the home of soul-liberty being the home of rampant individuality. Newport had “higher civic or communal sentiment, a more educated public spirit, a profounder political consciousness.” The best lawyers, ablest politicians and public men lived there. Sectional, local “Rhode Island men” broadened out at Newport, as government went on. 70 Ante, p. 40. |

106

the expulsion of Quakers from Rhode Island,71—would give him a high, permanent place in history.

Governor William Coddington died in office. As he built the first brick house in Boston, so he laid the foundations of Newport on a solid basis, being pioneer in her commerce. In his course as judge, he probably made the first code of laws, which lasted for generations, and without which we may safely assume, Rhode Island never could have been developed. But in the significant words of a judicial descendant, “he had in him a little too much of the future for Massachusetts, and a little too much of the past for Rhode Island, as she then was.”72 This tendency resulted in the vagary of “Usurpation.” He became a Friend and in his latter years was again active in public affairs, in a legitimate way. As we have noted above,73 Rhode Island owes him a great debt.

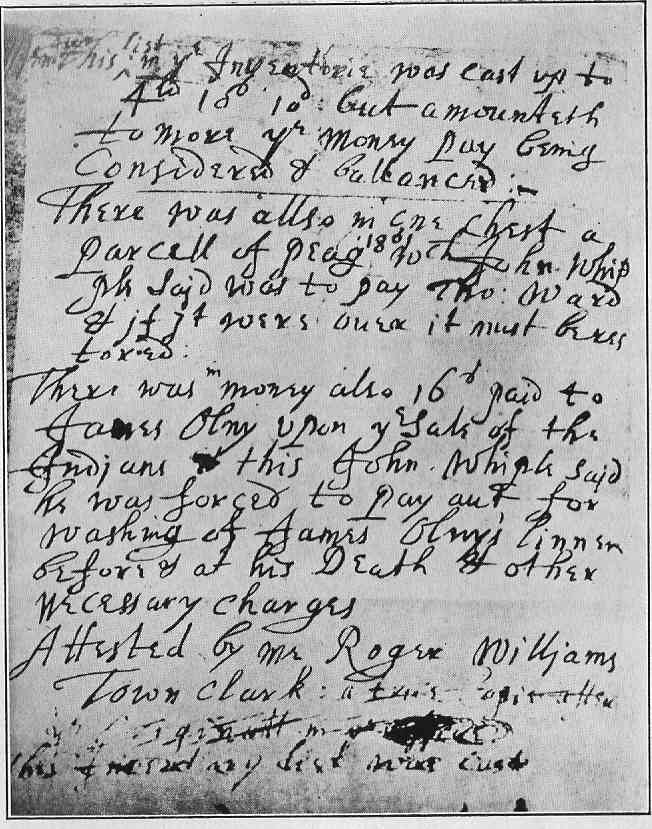

When life was monotonous and news-prints were unknown the talk of Towne Streete was of constant interest. Beyond this, scandal, slander and gossip too often filled the air and occasionally went on record. August 27, 1684,74 S. Bennett was obliged to retain John Whipple, Jr., an attorney to defend him against the suit of Bridget Price. In September, Bridget signing with an X declares that the said Bennett in his own home charged her with being “a thiefe, a ———, and a vagabond.” Even Boston furnished its share to these proceedings, for Thomas Clarke in “his pewtour’s shopp “there, had an altercation with one Mary Brattle (not connected with Brattle Sq. probably) and followed her to Providence, where he arraigned her through the busy attorney Whipple,

|

71 “R. I. Col. Rec.,” Vol. I, pp. 376-380. 72 C. J. Job Durfee, “Historical Discourse,” p. 16. 73 Ante, p. 64. 74 “E. R. Prov.,” XVII., p. 41. |

107

Nov. 24, 1684.75 Whipple deposed for Clarke that in the said shop Mary Brattle demanded the “key of a house of office.” Clarke refused and Mary gave him “very Taunting speeches.” In answer, Clarke said, “prateing hossey.” Then Mary called Clarke “Beggers Bratt, and Cheate, and sayd shee kept a better man to wipe her shoees.” Then the said Clarke bid her get out, “for yov are prateing hossey, for yov had need to have had a hundred pounds Bestooed upon you at a boardeing scoole; to learn manner and breeding then shee ye said Brattle called ye sayd Clarke Rouge and soe went out of ye shopp.” The views of Clarke on education indicate the standard of culture prevailing among Boston pewterers.

However simple the social proceedings of the plantation, man and woman were sometimes unaccommodating in their vital intercourse. Whatever Margaret Abbott’s faults may have been, her explicit consort Daniel shines forth in no favorable light. Aug. 7, 1683,76 Abbott records his woes. “Through her Maddness of folly and Turbulency of her Corrupt will, Destroying me Root and Branch, putting out one of her owne Eyes to putt out Both mine. And is since departed takeing away my Children without my Consent and plots to Rifle my house to accomplish her Divelish Resolution against me.”

The spirit of peace hovered over another couple even in temporary estrangement. In this methodical fashion, they wore no sackcloth, but coming before their townspeople, they laid these substantial foundations for new marital relations. It is to be hoped that gay Cupid smiled on sober Justice, Dec. 29, 1699.” Agreement between

|

75 “E. R. Prov.,” XVII., p. 53. 76 Ibid, Vol. XVII., p. 37. 77 Ibid, Vol. V., p. 9. |

108

George Potter of Mashantatuck and Rachel his wife. She had with his “Consent and in hope of More peaceable liveing withdrawne herselfe and removed to Boston for sometime; and now finding it uncomfortable78 so to live and I being desireous to Come together againe, doe here for her further in Couragement and to prevent after Strifes and Alienations propose these Artickles. 1. She has given some things to her children. I shall never abraid her or seek a return to them. 2ly. Our house and land, if I dye before my wife she shall have it during widowhood and bearing my name. In case of Marriage, she shall enjoy 1-3, other 2-3 to my nearest Relations—at her decease her 1-3 to return. 3ly. I will not Sell or Mortgage any house or lands. 4ly. I promise to dwell in all loveing and quiet behavours. All Moveables as Cattell and household goods vessels or Boates she shall possess solely at my decease.”

The wife on her part appreciated such liberal treatment and showed that she was not making a merely formal or ineffectual contract.

“5ly. I Rachell Potter if it appear I have disposed of more than one bed since our departure, said bed shall be returned.”

In treatment of the poor, especially those fallen from a better estate, the finest qualities of the planters stood out in full relief. The support of the poor caused a substantial portion of every rate assessed. Once within the town, the poor were well cared for, though the burghers were constantly struggling against tramps, vagabonds and persons whom they did not choose to admit as citizens.

|

78 Mark the delicate variations and subtle suggestion in this renewed courtship. Both “uncomfortable” and he ready to give further encouragement. Modern Newport might learn some things of old Providence. |

109

However illiberal or undesirable this municipal hostility appears to be now; then it seemed to be the only mode of ruling a plantation.

We cannot follow in detail the administration of particular cases, though they are interesting and often pathetic. A negro, not enslaved, had rights, for Samuel Beep’s servant appealed to the town, Feb. 19, 1672,79 Reep having refused to “Receue him or Releaue him for his presant nessety.” John Joanes80 frequently appears, declining into the vale of years, and always as “our Ancient Neighbour.” Dec. 24, 1677, repairs were ordered for his house to make it “comfortable for the winter.” Nov. 24, 1680, the same ancient neighbour is allowed maintenance according to “his minde and will.” The old gentleman’s will could still prevail over the committee, for he repudiated their arrangement Dec. 15, and asked for an inventory of his estate. In April the poor “neighbour” submitted to the inevitable resigning estate to the town. House and lot were sold by “inch of ye Candle, highest bid, £17.6. May 3, 168481 His inventory showed £8.4.1, of which £2.4. was in wearing apparel. Jan. 27, 1682-3, Joseph Smith received a grant of forty feet square on Towne Streete—as they were constantly being made—on condition that he lay a row of “steping’s stones along the fence of John Joanes’ lot.”

Wm. Harris died in London, but we may cite from his inventory, January 21, 1681,82 some items which are interesting from every point of view. He had a story and a half house, with many barns and cribs well stored and perhaps the largest estate in the colony, leading a

|

79 “E. R. Prov., Vol. VIII., pp. 23, 88, 89, 123. 80 Ibid, Vol. III., p. 227. 81 Ibid, Vol. VI., p. 122. 82 “Early Rec. Prov.,[”] Vol. VI., p. 75. |

110

most active and enterprising life. Pewter was the main article in the outfit of table and kitchen, and his stock was worth £2. 0. 4., including syringe at 5s. 6d., and a chamber pot at 1s. 6d. These durable conveniences were common and in this instance coincided in value with a copper candlestick. This metal was unusual, and the porringer—a dish so much used in pewter—stood at 1s. Brass kettles and candlestick £1. 0. 6., and this metal as well as iron was used in almost every kitchen; there was also wooden and earthen ware. We have referred to Harris’ library, which was then far better than that of the ordinary man of affairs. Fortunately, the list may be given in detail. 1 Dixonary 6s.; London Despencettorey 8s.; Chururgion’s mate 10s.; Norwood’s Tryangles 5s.; 1 Bible 2s. 6d.; 1 Great do 5s.; 1 Contemplations Morall and devine 2s. 6d.; Cooke’s Commentarey upon littleton £1. (this was given to Thomas Olney); The Compleat Concordance Clarke 8s.; Touchstone of wills 2s.; 3 bookes 1s.—1 naturs Explecation; 1 treatise of faith; 1 ye effect of warr; 5 books 6s.—Gentleman Jockey, Gospel Preacher, New England Memorial, Method Physic, Introduction Grammar, Lambath’s perambulations, not valued; Statute poulton £1. 15.; Declarations and Pleadings 3s.; The Executors Office 2s.; Exposition law terms 2s.; layman’s lawyer 2s.; Saw juryers 1s. 6d.; Justice Restored 1s. 6d.; Dallon’s Country justice 5s. A set of surveying instruments.

A collection of books in a community where they were scarce; it was very strong in law, moderate in theology and ethics, sufficient in medicine and surgery, useful in surveying; altogether the mental nutriment of a powerful citizen who touched life on all sides.

As Wm. Harris was in the way of the time a statesman, Thomas Olney, called Senior in distinction, was a politician

111

and manager of men. One of the original thirteen proprietors with Williams and Harris, the first treasurer of the town; he was often town clerk, when the clerk was the mainstay of order, and of such propriety as prevailed. He was very acrimonious in the dispute with George Fox and the Friends. His disputation mingled politics with doctrine in a manner worthy of an ecclesiastic. He was always prominent in the affairs of plantation and colony. October 9, 1682,83 his inventory showed the moderate personal estate of £78. 9. 5., of which only £3. 17. was in wearing apparel. There was a change in the dress of this class of citizens in the next score of years. In the pioneer period and until after King Philip’s War, the planters were homely in all their habits of life. Brass was represented in 3 kettles £1. 6.; in a candlestick and other articles 5s. Pewter dishes £1., with 1 dozen trenchers 6d. The furniture was meager, 2 old joynt chairs and a joynt stool 3s. 6d.; 1 great chair 1s.; 1 “fourme” 6d.; 1 small table 4s. There was no loom or spinning wheel, but considerable evidence of home-made cloth. As 2 3/4 yds. Carsey 13s.; 10 1/2 yds. blanketing £1. 5.; 4 yds. woollen homespun 7s.; 2 1/2 yds. home-made cloth 4s. 2d. Almost 2 yds. white fulled cloth 4s. Dry hides, including what Thomas Olney took to tan; £2. 14. in money and 4 cows at £10. Evidently he farmed only for his own household, and commingled other interests, as in tanning, weaving, etc. He did not read as Harris did, for his library was small, even in a small environment of books. One bible 4s.; 3 old pieces bible 2s. Three books—Ainsworth’s Annotations, a Concordance, “fisher’s Ashford Dispute”—were valued at £1 10. Though church connections were few and not very binding, the Scriptures were clearly used in a practical way. In the

|

33 “Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. VI., p. 90. |

112

dearth of printed matter, pieces and bits of Bibles and Testaments were appraised in many inventories.

In the same month passed on John Smith, the miller; not so conspicuous or famous, but an influential factor in the communal life of the early plantation. Before there was a room of size in a dwelling, or a tavern to accommodate loiterers and talkers, the town-mill gathered a throng who discussed the whole affairs of those concerned—political, religious, or social. Seated on bags of grain, they did not mind the rumbling of the stones, as they disputed and threshed out matter for a future town meeting. John Smith, of the widely extended name, hospitable and hearty, must have made happy the early townsmen assembled for these rare opportunities. His estate was £146. 5. 3.,84 the corn-mill, house over it and all appertaining was valued at £40; one-seventh part of the saw-mill adjoining £3. 10. The furnishings were simple, 2 bedsteads and bedding £2.; 1 do and bedding “in ye lower Roome” £3; Brass and copper kettles £2. 16.; 2 tubs and tobacco 5s. 6d. Flax 10s. Cattle with 2 mares, 3 young horses, 16 swine £22. 9. “Ye Booke of Martirs” 15s. Old bible, “some lost and tome, 9d.”

In 1688, died Roger Williams the founder. He built the state even better than he knew—and his knowledge was great for his time and opportunity. The principles he conceived and set forth were larger than any man; as the centuries have shown.

An important function in the early life of New England lay in the making of apprentices; binding out a minor to learn an “art or mystery.” When children were bereaved, it often created a temporary home for a waif, and finally gave him capacity for a good livelihood.

After the vocation of a smith, one of the greatest

|

84 “Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. VI., p. 72. |

113

needs was for a weaver. Cloth making was carried on in nearly every household, and sometimes experts went about using the family looms. Again, there were shops for weaving yarn taken from farmers who carded their own wool and spun it on domestic wheels.

July 3, 1674,85 there appears a name well known in textile industry. Moses Lippitt, with the consent of his father-in-law, Edward Sairle, and Anna Sairle, his mother, was apprenticed to William Austin for fifteen and one-half years and two months to learn the “art and trade” of a weaver. There were the usual covenants and at majority he was to have his freedom and “two sufficient Suites.” If Austin should die, he could assign Lippitt for the balance of his term.

March 30, 1696, John Sayles took Job Liddeason for 14 years, who promised to keep his master’s secrets, not to contract matrimony, nor frequent taverns or ale houses, nor absent himself night or day. Sayles on his part was to give the “Nessessaryes to an apprentice doth belong” and to “endeavour to learne him to Read and write.”86

Jan. 11, 1708-9,87 Thomas and Hannah Joslin took Jerusa Sugars from her mother; who was to pay them £8 in silver and 40s. in a yearling heifer. The payment was changed Jan. 20 to £10. silver. The child was about one year old, and was to receive sufficient board, lodging and apparel for a servant. The Joslins were “carefully her to keepe” and to learne “the said Jerusa Sugars the art and mistry of a Tailor, well and sufficiently to make apparill both for Men and Women and to learne her to Read well.” At eighteen years of age, she was to receive two sufficient sutes.”

|

35 “Early Rec. Prov.,” Vol. V., p. 292. 36 Ibid, p. 147. 37 Ibid., p. 18. |

114

Richard Arnold in his will, 1708, directed his son Thomas to free the negro Tobey in February, 1716-7, when he would be 25 years of age, and should receive two suits of clothes.

Nov. 25, 1687,88 Gideon Crawford, a Scotchman, was granted liberty to “Reside and here to follow his way of dealeing in goods.” This was a memorable event, for he was the first to develope an orderly trade among the not too liberal planters of Providence. Commerce was not unknown, for William Field, in his will, May 31, 1665,89 gave to his “cousin Thomas now at Providence, all that Cargo that is now upon sending to the Barbados.” And in further bequest gave to his wife “that which is as Yett coming to me from the Barbados.” But the traces of exports are few, and though Mr. Dorr excludes them altogether in his view of industrial progress in the latter seventeenth century, commerce prevailed, if it was not important. The community pursued agriculture too closely, and suffered from the contracted ideas prevailing in consequence. It was not until 1711, when Crawford and his imitators had taught the value of enlarged intercourse with the world that Nathaniel Browne established ship-building at the head of the “Great Salt River.”

The most definite account of Rhode Island exports appears in William Harris’ testimony in London before Sir J. Williamson,90 in 1676. This was carried on from Newport, but Providence must have profited indirectly through the demand created for produce. There were more sheep in Rhode Island than anywhere in New England. Wool was exchanged with France for linen. Deerskins,

|

88 “Early Rec. Prov.” Vol. V., p. 170. 89 Ibid, Vol. VII., p. 225. 90 “Col. Br., State Papers, 1675, 1676,” pp. 221, 222. |

115

sugar, and logwood went to England for cloth and iron ware. Horses, beef, pork, butter, cheese, flour, peas, and biscuit went to Barbados for sugar and indigo. There was “a great trade” in cod, haddock, and mackerel with West Indies, Barbados, Spain, and the Straits. I think much of this fish came from Massachusetts in exchange for West India goods. He mentions obtaining linsey-woolseys and other coarse cloths from Massachusetts.

Citizens of another sort were admitted occasionally, though many were refused. William Ashly and his wife were driven out from “Wels” by Indian depredations to Boston. Then they came to our plantation, where Abraham Hardin permitted them to unload their house-hold goods, “which I took to be a loving-kindness in distress.”91 He asked for a habitation in 1693.

The Indians, though much weakened, were a factor and caused alarms in the quiet life of the plantation. April 3, 1697,92 there had been “a late in Curtion and invasion by the Cruel and Barbarous Indian Enemies” The Council appointed twenty prominent citizens to command ten men each, and to “scout, kill and destroy.”

We have noted the political organization of government under the charter. Quite as important was the character of the judicial system introduced then.93 The chief officers were a President and four assistants—one from each town—making a General Court of Trials for the Colony. This was the origin of our present Supreme Court; lesser tribunals appealing to it. As showing the curious interplay of English legal procedure, with the planters’ notions of independence and town government,

|

91 “Early Rec. Prov., Vol. XVII., p. 146. 92 Ibid, p. 163. 93 Durfee, “Judicial History R. I.,” (Tracts), p. 11, et seq. |

116

there had been a mingling of the head officers of a town with the Court, and they had sat together. This was remedied after 1647 by rules “to add to the comely and commendable order of the Court.”

The General Assembly had full governmental powers, and consisted of the Governor, Deputy-Governor, ten assistants, and a body of deputies The deputies, or house in modern parlance, were a purely legislative body; the Governor, Deputy-Governor, and assistants (senate) had magisterial duties as well. After the old court became mainly a tribunal for appeals, the new court exercised original jurisdiction.

In 1749 a change in organization was effected. From the Governor, Deputy and ten assistants, five judges, a chief and four associates were selected. In 1781 final separation was made between legislature and judiciary, for members of either house of the Assembly were forbidden to sit as justices of the Supreme Court.

The earlier judges included Roger Williams, Samuel Gorton, John Clarke; not lawyers, but men of broad culture for the time. Perhaps they were quite as useful in a common world as the strictly trained Puritanic jurist, steeped in Judaic precedent and tradition. The whole system was a local and essential outgrowth of the soil. The orderly sense of law, transported with every English immigrant, was incorporated with an intense individual desire of the citizen to imprint his own ideal of immediate justice on every public act. Some of the most vital issues of Rhode Island life—potential for good or evil—were born just here.

We should note that this remarkable creation of a substantial judiciary out of very rough material, which worked out justice according to English law, was accomplished by men outside the lines of Catholic or Protestant

117

education. Churches do much good, as well as some ecclesiastical harm. In Massachusetts and Connecticut they educated the people. Outcast Rhode Island must educate itself, not by academic forms, but through the business of a hard, stringent life. A university was impossible, but nature lived and moved all about these men. After all, to do is better than to construe or to imitate. William Harris, Thomas Olney, Arthur Fenner, Pardon Tillinghast, the cooper-preacher, and many less conspicuous, took and assimilated life from the kernel.