|

|

|

Japanese

Pirates and Sea Tenure in the

Sixteenth Century Seto Inland Sea:żż

A Case Study of the Murakami kaizoku

Peter

D. Shapinsky

University of Michigan

[Noshima Murakami Takeyoshi]

is called the Noshima Lord and is exceedingly powerful; on

these coasts as well as other provinces' coastal regions,

all are afraid of him and so every year send him tribute.1

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed an expansion

of the maritime networks transmitting goods and culture within

the Japanese archipelago and between Japan and East and Southeast

Asia. To reach the ports of Hy╗go and Sakai, two of

the main termini in the Japanese archipelago that fed the

capital region, ships usually passed through the Seto Inland

Sea,2

the narrow body of water connecting the three main islands

of Honsh˛, Shikoku and Ky˛sh˛. This sea-based commercial

growth developed as centralized authority over the archipelago

gradually disintegrated.

Pirates of the Seto Inland Sea such as the powerful three

branches of the Murakami familyŃNoshima, Kurushima, and Innoshima—took

advantage of the chaotic decentralization to carve out maritime

domains for themselves. Through manipulation of competing

landed patrons3 as well as independent marauding and

extortion, pirates expanded their territories on the sea from

small fishing villages to formal and informal domains that

stretched across the Seto Inland Sea. The formal domain

represented the maritime territories to which pirate lords

held formal title such as fishing villages, toll barriers,

and ports. The informal domain reflected the reach

of a pirate band's reputation and influence beyond the formal

domain. The extent of the informal domain fluctuated

depending on the possible range of ships and the level of

terror instilled by the possibility of violent reprisal.

I will explore the formal and informal nature of piratical

sea-tenure through a two-part case study of the well-documented

Murakami family. The first part examines epistemologies

of maritime violence in medieval Japan and analyzes pirates

with a sea-centered, social-ecological perspective. The second

part investigates the nature of piratical sea-tenure through

an exploration of how the Murakami pirates administered their

formal and informal domains.

The Social

Categories of Pirates in late-Medieval Japan:

The term I translate as pirate, kaizoku ( ),

is a representational noun used in a variety of ways by landed

elites to refer to practitioners of maritime violence. The

term refers to those who performed unsanctioned, violent activities

such as the extortion of protection-money from passing ships

at toll barriers and assaulted shipping. But the word

kaizoku also encompasses pirates who entered into patronage

agreements to operate toll barriers, escort ships, fight sea

battles, launch night raids and sneak attacks, and take captives

for sale as slaves. Warrior law codes from the Kamakura through

the Sengoku period outlawed kaizoku, while at the same

time these same law-dispensing institutions employed mariners

they called kaizoku for a variety of maritime functions.

As in the case of the Murakami family, the term kaizoku

can also refer to the local elite warrior leaders of the seafaring

bands. Increasing acceptance of patronage offers

from landed powers earned some pirate bands in western Japan

like the Murakami families the designation "protection-duty

bands" (keigosh˛, ),

is a representational noun used in a variety of ways by landed

elites to refer to practitioners of maritime violence. The

term refers to those who performed unsanctioned, violent activities

such as the extortion of protection-money from passing ships

at toll barriers and assaulted shipping. But the word

kaizoku also encompasses pirates who entered into patronage

agreements to operate toll barriers, escort ships, fight sea

battles, launch night raids and sneak attacks, and take captives

for sale as slaves. Warrior law codes from the Kamakura through

the Sengoku period outlawed kaizoku, while at the same

time these same law-dispensing institutions employed mariners

they called kaizoku for a variety of maritime functions.

As in the case of the Murakami family, the term kaizoku

can also refer to the local elite warrior leaders of the seafaring

bands. Increasing acceptance of patronage offers

from landed powers earned some pirate bands in western Japan

like the Murakami families the designation "protection-duty

bands" (keigosh˛,  ).4 ).4

Institutions that sponsored pirates included a range of land-based

institutions including temple-complexes like T╗ji and warlords,

though by the sixteenth century, warlords made up the majority

of those offering patronage opportunities to pirates.

Sponsorship suited both landed elites and pirates alike. The

pirates hoped to gain further control of essential strategic

maritime locations and additional license to engage in aggrandizing

activities such as attacking shipping and extorting fees for

safe passage. Landed patrons such as warlords hoped

to acquire indirect control of remote maritime regions that

might otherwise have escaped their grasp.5 This mutually beneficial

relationship allowed pirates to extend their domain on the

sea further than if they remained independent maritime bands.

For instance, in the summer of 1582, the Noshima Murakami

pirates with M╗ri sponsorship 'legitimately' pillaged the

ships of the Kurushima Murakami (who had recently left M╗ri

patronage and become an 'enemy'), and expanded their holdings

to include Kurushima Murakami holdings on the island of Yashiroshima.6

The patron-pirate relationship was recorded in the land-based

language of retainership,7

but should be understood as having operated less as a hierarchy

than as a symbiosis. The patrons held higher status,

but because the patrons had no authority or expertise over

the sea, they needed the pirates to accomplish any sea-based

objectives. Pirates retained their autonomy and

the patrons' higher status allowed pirates to practice their

piratical activities legitimately, but pirates did not necessarily

become submissive to the landed power. Many pirate bands

felt free to ignore the dictates of their oaths and accept

alternate patronage offers.

Patronage was a continuum of attachment that bound pirates

and landed institutions together to varying degrees.

Some pirate bands refused all patronage offers while others

contentedly remained with a single sponsor their entire careers.

Often the pirates hired to suppress other pirates would become

the aggressors in turn, extorting and attacking seaside communities

in a continuing cycle of patronage and brigandage.8 Pirate bands like the Noshima Murakami retained

a strong sense of independence, entering into and quitting

patronage agreements, and manipulating competing landed factions

against each other. For example, between 1542

and 1582, the Noshima leapt back and forth among warlord families,

especially the K╗no in Iyo, the ąuchi and M╗ri in western

Honsh˛, the ątomo of northern Ky˛sh˛, and even considered

joining the first unifier, Oda Nobunaga. These

patronage trends conform to Fujiki Hisashi's classification

of pirates as mercenary 'irregulars' in medieval armies whose

actions were looked down upon by the elite samurai, but nonetheless

were regarded as indispensable.9

To counteract the weakness of these patronage ties, landed

sponsors sent to daughters to pirate lords to try to tighten

the bonds between patron and pirate through marriage alliances.10 On other occasions, sponsors held members of

the pirate-lord's family hostage11 to ensure 'good behavior.'

But for the most part, the initiative in accepting or refusing

sponsorship lay with the kaizoku.

The correspondence and other documentation that resulted from

this system of patronage created a corpus of materials that

has allowed the voices of pirates to survive. At the

same time, this patronage documentation was recorded in the

language of landed-institutions and often reflects solely

the interests of those land-based elites. Moreover, only those

pirates who entered into sponsorship relations remain significantly

in extant medieval records. At the remotest end of the

spectrum existed pirates who chose not to negotiate the patron-pirate

relationship. Without the link to the records of landed

institutions, these unsponsored pirates do not appear with

much detail in extant sources.

The resulting unevenness of extant sources coupled with the

ambiguity of terms used for maritime violence has caused historians

until recently to focus on kaizoku as either purely

seafaring criminals or as ship-owning warrior vassals.12 Recent scholarship by Amino

Yoshihiko, Sakurai Eiji, and others has begun to re-contextualize

pirates from two major perspectives. The first viewpoint

utilizes comparisons with mountain bandits (sanzoku)

and outlaws (akut╗) to understand pirates as a larger

social phenomenon of banditry in medieval Japan. The

second perspective and the one important for this paper re-envisions

piracy as part of a continuum of occupations of people who

made a living from the sea.13

This point of view suggests a social-ecological perspective

that examines occupations, control of resources, and ties

to networks of distribution and exchange to take into account

how seafarers and the maritime environment affected each other.14 A social-ecological framework

allows the historian to understand the distinctively sea-based

social, economic, and environmental context that pirates lived

and worked in.

From the view of the sea, people of the sea in medieval Japan

possessed a mastery of the knowledge and skills of seafaring

that fundamentally separated them from the landed populations

and enabled a highly mobile lifestyle. Without sufficient

maritime power of their own, landed powers competed to offer

the local warrior leaders of maritime communities patronage

opportunities in shipping, warfare, and pirate suppression.

Well aware of their advantage in the maritime realm, pirate

lords demanded legitimate title for sites and activities consistent

with their maritime domain.15 The lack of maritime expertise and concomitant

dependence on the seafaring population by landed institutions

only increased the illegitimacy of pirates and the maritime

population in the eyes of landed elites. Landed elites

regarded the littoral inhabitants as a breed apart, calling

them sea-people ( ).

16 ).

16

With their status of local elite warriors, pirate lords ruled

over communities of these sea-people in their formal domain.

Pirate crews drew from the ranks of such fisherfolk, sailors,

shippers, harbormasters, and salt-makers. So in a sense

pirates fished, managed harbors, maritime commerce, and dealt

in countless other maritime occupations in addition to the

violent activities fitting into the rubric of kaizoku

and protection duty. The administration of maritime

labor created sea-based networks of sea-people that increased

the reach of pirates' reputations, their informal domain.

For example, the Noshima had no formal holdings in the port

of Akamagaseki, the western gates to the Inland Sea, but through

their patronage relationship with the M╗ri, the Noshima gained

administrative control over the Sak╗ family of harbormasters

in Akamagaseki.17 With their contacts in Akamagaseki, the

Noshima learned of what ships entered the Inland Sea and expanded

their influence through a network of sea-people.

Kaizoku inhabited a distinctly maritime realm. To

take advantage of their mastery of the maritime environment,

kaizoku of the Inland Sea based themselves in castles

on small mountainous islands and peninsulas that overlooked

the most traveled channels. Fortified control of these

islands and the possession of sufficient ships and mariners

gave the kaizoku the ability to strangle shipping lanes

with a network of fortifications and private toll barriers

located at various choke-points of the Inland Sea. The

pirates often selected islets near larger islands to secure

markets and provisions, and yet retain a position on the sea.18

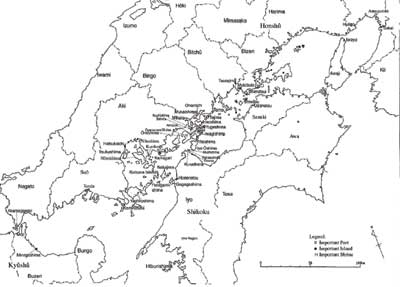

For example, the island-bases of the Kurushima and Noshima

are both under a kilometer in circumference and lie among

larger islands and near the Shikoku mainland in the midst

of the swift currents that run between Honsh˛ and Shikoku

(see map).19

Despite the small size of most of these kaizoku bases,

the fortified, mountainous islands contained permanent settlements

and were fully capable of maintaining even the largest of

the late sixteenth-century turreted dreadnoughts, the atakebune,

often 30 meters in length with both sails and oars.20

Pirate lords controlled an array of sites of overlapping maritime

praxis within the formal domain such as fishing villages,

ports, and toll barriers. Japanese pirate bands

tended to be community-based, taking their name from their

lord and his putative site of origin. As local warriors,

pirate lords led a hierarchically structured band incorporating

family members, retainers, and conscripts and volunteers from

seaside villages under their control.21 Pirate leaders administered the formal

domain directly or by confirming retainers' rights to administer

these territories on their behalf.22 Not only territory,

but also toll-assessing rights within the formal domain were

fully heritable and kept within the lines of pirate lords.

Piratical influence radiated outward from this formal domain

to create the informal domain. The reputations of kaizoku

permeated via networks of patronage, commerce, and maritime

laborers and reflected the perceived effectiveness of a particular

band's toll barriers, protection-duty, and punitive might.

This paper investigates the administration of maritime domains

from three angles, the administration of littoral habitations,

the management of maritime labor, and the operation of toll

barriers and protection-duty.

To give an example, at the height of their power (c. 1583),

the formal domain of the Noshima Murakami kaizoku stretched

east to west (see map) from the Shiwaku islands, to parts

of Iwagishima and Ikinashima,23

to their home islands of Noshima and Mushishima, as well as

the Kutsuna and Futagami islands,24 part of Yashiroshima,25 Kaminoseki,26 Minogashima.27 As will be seen, from this formal domain, the

Noshima affected policies from the important port-city of

Sakai to the gates of the Inland Sea in the straits of Shimonoseki.28

Pirate Administration of littoral settlements

To aid in the administration of the formal domain, pirate

lords often issued law codes. Hokkenotsu Han'en issued

the following set of bylaws for the population of the tiny

island of Hiburi29 (see map) located off

the southwest coast of Iyo in 1576.

When performing duties for

patrons30

on sea and land, they are to be performed according to our

bylaws.

Ó Ships entering or leaving

the harbor who wish to engage in commerce must receive permission

from the Harbor Council.

Ó Objects that are spotted drifting

or washing ashore are to be reported to the Harbor Council.

Tensh╗ 4 [1576] 11th month, felicitous day

[From] Hokkenotsu Han'en

[To:] The Hiburi Islanders31

This short code demonstrates the degree to which pirates as

sea-peoples participated in a continuum of maritime activities

from protection-duty to commerce. When performing duties

for patrons, the bylaws of the pirate-lord and the pirate

band, not the patron dictated the performance of piratical

activities. The code regulated the commercial

intercourse of the island. Only by receiving permission

from the island's ruling council (probably by paying a fee)

could ships from outside using the harbor also engage in commercial

activities on the island. As potentially very valuable

items like whales and driftwood might wash ashore, the pirate

lord had first salvage rights. Consequently, the inhabitants

had to report any sighting of seaborne detritus.32

With its economic and strategic value as a harbor-bearing

island on the shipping routes, small settlements like Hiburi

eventually had no choice but to accept the overlordship and

bylaws of one or more competing pirate lords wielding their

authority as local warrior elites. The history

of Futagami Island in the Kutsuna island-chain epitomizes

the administrative situation that might develop as multiple

pirate-bands claimed lordship over the island (see map).33 Like other maritime

communities in Japan, the Futagami Island population lived

in settlements defined by maritime function—Bay and HarborŃas

well as several production districts.34 Led by the Futagami kaizoku,

the inhabitants of the island fell under the suzerainties

of the Noshima, Kurushima, and other pirate families from

the early 1500's until the Noshima Murakami conquered Futagami

in 1582.35

The Futagami kaizoku and island inhabitants served

as pirates, sailors, and corv■e labor in various pirate bands,

chiefly the Kurushima and Noshima.

Before the 1582 Noshima conquest, the Futagami inhabitants

served various pirate overlords and paid assorted seasonal

and corv■e proxy taxes. These pre-1582 pirate lords such as

the Kurushima Murakami as well as the Noshima extracted allotments

of agricultural and marine products such as summer wheat,

sea cucumbers, firewood, seaweed, oysters, and clams. Kurushima,

Noshima, and other pirate bands all dispatched agents to administer

their interests on the island and included privileges for

these agents as part of their taxation apportionment arrangements.

For example, the Kurushima Murakami agents received rights

to sea cucumbers harvested by the Harbor and Bay villagers.36

Trade in the products of the maritime environment such as

sea cucumbers, shellfish, fish, seaweed, as well as forestry

products like firewood and naval stores tied Futagami Island's

inhabitants and their extractive pirate overlords to the Inland

Sea's seaborne commercial networks. One of the most important

of these networks linked Futagami and other Inland Sea locales

to the religious center and flourishing markets located on

the island of Itsukushima. 37 (see map) The producers of Futagami

regularly sent rice, rice cakes, unglazed pottery, and many

kinds of alcohol to the shrine.38 The Futagami family assisted

the Kurushima Murakami pirates in providing protection-duty

for ships bound for seasonal festivals and markets on Itsukushima.39

Futagami's fish and shellfish either were consumed locally

or were salted for longer-distance trade. For

example, the Kurushima agents valued their sea cucumbers as

commodities as well as comestibles. In the spring of

1580, on behalf of the M╗ri, Noshima Murakami Takeyoshi entrusted

his Futagami retainers with the procurement of enough seafood

to victual his band. In return, the Futagami lord Taneyasu

sent nineteen rockfish to Murakami Takeyoshi as a gift.40 Warrior elites valued maritime produce

highly as gifts. Fish like bonito and sea bream brought

good fortune in battle to the recipient, so these fish were

often sent as presents to soldiers at the front.41 Warlords seeking

to gain advantage through the gift-economy of the warrior

class sought to bring pirates and seaside villages under their

sway.42

Futagami Island was also blessed with large amounts of timber

resources. Yearly, it sent firewood to the Kurushima

Murakami and others as tax in kind.43

Many places throughout the Inland Sea specialized in salt

production in the medieval period, making firewood a very

highly valued resource. The Futagami also sent wood

to be used in shipbuilding. In 1579, Tokui Michiyuki,

a pirate-lord allied with the Noshima Murakami pirates, ordered

100 tree trunks for use in ship construction.44

Pirates such as the Kurushima and Noshima Murakami participated

in medieval maritime commerce through administration of the

sea-peoples in their formal domain.

In 1582, the Noshima Murakami arrogated total control of the

Kutsuna archipelago including Futagami Island after defeating

the Kurushima Murakami and driving them from the region.

Noshima Murakami Motoyoshi then issued this set of laws for

those islands:

Laws for the Kutsuna Seven Islands

Ó The islands' inhabitants are

not to perform protection-duty.

Ó Coming and going by producers

in the service of retainers with holdings here is forbidden.

Ó When producers are crossing

the sea in any direction, it will be ruinous if they take

ship with retainers, so that is forbidden.

Ó When making crossings by ship

to perform services, conscripts and retainers of the various

islands are to go as far ąshima and Tsushima in both directions.

Ó There are to be no violations

of the aforementioned.

Tensh╗ 10 (1582) 4/25 Murakami Motoyoshi

To:] Kutsuna Temple and Shrine producers; Nuwa,

Tsuwachi, Futagami, Mutsuki45

Fully aware these islands contained a population of kaizoku

formerly under the dominion of multiple pirate overlords such

as the Kurushima Murakami, Noshima Murakami Motoyoshi restricted

the act of performing protection-duty to the Noshima Murakami

and their direct retainers. Because some Futagami fought

naval battles alongside the Kurushima against Noshima pirates

in 1582,46 Motoyoshi outlawed unsanctioned, independent action by kaizoku

in these islands to mitigate any possible return to the

Kurushima Murakami or other pirate band. Nor could the

Futagami or other Noshima retainers recruit producers (fisherfolk

and agriculturalists) into bands to attack ships or perform

autonomous protection-duty.

Similar to other laws issued throughout Japan in the late

sixteenth century to keep farmers and other villagers from

joining warbands, Noshima Motoyoshi hoped to prevent fisherfolk

and other ship-owning sea-workers from turning pirate or joining

other pirate bands. He hoped to restrict them solely

to activities related to maritime production, and so preserve

the peace imposed by the Noshima conquest. Similarly,

the Noshima dictated the shipping route for Futagami transport

and shipping vessels to avoid sites of potential danger (see

map). The Tsushima-Iyo ąshima route to and from Noshima forced

a northerly detour away from the enemy base of Kurushima to

avoid possible conflicts and chances to perform unlicensed

piracy. Through edicts such as these, pirates sought

to stop the same processes that allowed their expansive growth.

Pirates and Maritime Labor

Pirate-lords levied corv■e proxy taxes on the Futagami inhabitants

when actual corv■e labor was not required. Pirates often

administered shipping and transportation organizations in

their formal and informal domains and recruited from sea-peoples

inhabiting islands in their formal domain to swell the size

of their crews with fishermen turned conscript-sailors.47

The most detailed evidence of Murakami pirate involvement

with shipping organizations comes from the Shiwaku Island

chain eastward from Futagami across the Inland Sea.

The Noshima valued Shiwaku primarily as a source of seafaring

labor, though the Shiwaku inhabitants also engaged in fishing

and salt-production.48 Luis Frois wrote in 1588, "Shiwaku is a

port famous throughout Japan and is a base for many ships,"49

requiring a large population of both mariners and harbor workers,

a perfect labor pool from which the Noshima Murakami pirates

could draw. The Noshima Murakami expanded into the Shiwaku

island chain in the early 1530's50

and incorporated the resident mariners into their pirate band.

While the Noshima recruited mariners from Shiwaku for a battle

on behalf of the M╗ri in 1567,51

the first extant evidence of Noshima Murakami administration

of Shiwaku's harbor-workers and shippers dates from 1570.

At that time, the Noshima Murakami had accepted the patronage

of a bitter rival of the M╗ri, ątomo S╗rin. As

the following letter from S╗rin states, the Noshima Murakami

provided maritime transportation services and protection-duty

between Shiwaku and Sakai:

─ [R]egarding the transport

of people to Sakai. I am very pleased at Your Mobilization

to perform protection-duty on the way there. I am also

overjoyed to have received exemption from the tolls at Shiwaku

harbor─.

Eiroku 13 [1570] 2/13

S╗rin,

[To:] Murakami Kamonnokami [Takeyoshi]52

As administrators of the port of Shiwaku, the Noshima charged

anchorage tolls at the port of Shiwaku, for which the legitimizing

patron (at this time ątomo S╗rin) received an exemption.

They arranged for the transport of people and goods as well

as protection-duty to ensure that the ships reached their

destinations safely, in this case the important port of Sakai.

Their responsibilities also included ensuring that the various

members of the shipping guilds did not quarrel over duties

as in this letter also from 1570:

There should be no

dispute regarding the shipping service for the trip to the

capital by Honda Jibunosh╗ Shizuhide─.

Eiroku 13 [1570], 6/15

Takeyoshi,

[To:] The Shiwaku Island Shippers53

Takeyoshi here orders the coastal shipping organizations

under his control in the Shiwaku Islands not to quarrel over

the rights to transport the ątomo retainer Honda Shizuhide

to the capital region. With their control over

the Shiwaku islands and other littoral locales, the Noshima

controlled the collection of harbor fees, the transport of

people and goods,54 and protection-duty for those

ships, a veritable monopoly of the shipping industry.

This expertise in the management of ports and ships allowed

pirates to extend their influence beyond their formal domains

to harbor-workers in other ports. In 1574, after assuming

the wardenship of Kaminoseki castle, 55

Noshima Murakami Takemitsu administered the activities of

the Sak╗, harbormasters in the port of Akamagaseki (modern-day

Shimonoseki), on behalf of Noshima's patron of the moment,

M╗ri Terumoto.

Regarding the investigation

and passage [of ships] at this toll barrier, you have inherited

this duty from Sak╗ Saemonnoj╗. As per your request,

the issue was discussed in council and it has been approved─.

Tensh╗ 2 [1574] 11/3

From: Murakami Takemitsu (in Kaminoseki)

[To:] Sak╗ T╗tar╗56

The M╗ri delegated the administration of the Sak╗ to the

Noshima Murakami pirates to ensure that the Akamagaseki port

and toll barrier ran properly. In this document, the

Noshima add their validation to confirm the succession of

Sak╗ rights to operate the toll barrier of Akamagaseki.

This confirmation indicates that the Noshima oversaw the Sak╗'s

collection of harborage fees and inspection of ships that

passed through the port. Though the Noshima Murakami had no

direct control over the port of Akamagaseki, their administration

of harbormasters extended their informal domain and piratical

influence through a network of sea-people. As Akamagaseki

was the gateway to the Inland Sea from East Asian waters,

any ship engaged in overseas trade passing through the Inland

Sea entered the influence of the Noshima Murakami pirates

because of Murakami relations with the Sak╗.

Toll Barriers and Protection-duty

Toll barriers and the performance of protection-duty

represent the simplest form of piratical sea-tenure and came

to define the extent of kaizoku formal and informal

domains. The late sixteenth-century Japanese-Portuguese dictionary

specifically links pirates with the operation of toll barriers.57 Often under the pretext

of collecting money or goods for a local religious site, a

small seaside community like Noshima or Kurushima would supplement

income garnered from fishing or salt production by intercepting

passing ships and charge fees for safe-passage or the use

of their harbor.58

For example, in 1550, a traveling monk recorded that a pirate

known as "Toll Barrier Captain" charged safe-passage fees

called "ritual donations."59

Pirates found toll barriers especially effective means of

collecting income without destroying the source because—as

in other pirate communities around the world—kaizoku

lived in a symbiotic relationship with mercantile shipping

and landed powers.60

Usually, only if the ships refused to pay did pirates attack

them.

Pirates most often operated toll barriers to extort protection

money from passing ships for a guarantee of safety and personal

escort. In his history of the medieval toll barrier,

Aida Nir╗ described an overlapping typology of toll barriers

that served as sources of funding for religious institutions,

personal economic gain, and bases for police and military

action in the medieval period.61

Pirates took advantage of the medieval understanding of the

multipurpose nature of the toll barrier to force passersby

to pay for safe passage.

This protection duty fell into two categories: either pirate

lords would dispatch ships to guide and guard paying vessels

for a predetermined distance or pirates would board and travel

along with the paying vessel. In 1420, the Korean emissary

Song Hui Gyong recorded that two pirate bands had split the

Kamagari region of the Inland Sea between them. To traverse

safely from one side to the other, travelers had to pay for

a member of one gang to take them safely through the territory

of the other.62

Song's description demonstrates how toll barriers and the

performance of protection duty from the barriers defined both

the formal and the informal domain. Barriers might be

placed at a strategic site near the boundaries of a pirate

band's maritime territory. Sakurai argues that as kaizoku

operated toll barriers to charge safe-passage fees, the barriers

marked the transition from the world of the land to the dominions

of the people of the sea.63 Travelers reporting

their experiences at toll barriers and having to pay for protection

duty spread word of the pirates and increasing the reputation

of the band. As time passed, toll-barriers became hereditary

parts of the formal domain. A will of the Innoshima

Murakami family from 1483 contains a record for harbor tax

rights among a list of family holdings.64

Receipt of the right to levy tolls legitimately might induce

pirates to accept the patronage of one warlord over another

and expand both the formal and informal domains. In

1543, as part of his plan to gain control over the lucrative

trade with Ming China through dominion of the Inland Sea shipping

lanes, the warlord ąuchi Yoshitaka authorized the Noshima

Murakami to operate toll-barriers at strategic points such

as the religious-commercial center of Itsukushima. The

Noshima Murakami intercepted, inspected and assessed a safe-passage

toll upon the China-trade ships passing through the Inland

Sea determined by the amount of goods the ships carried.

The acquisition of privileges to conduct this legitimized

piracy swayed the Noshima Murakami to leave their patrons,

the K╗no family, in favor of the ąuchi, despite the fact that

the K╗no and ąuchi were embroiled in violent conflict at the

time.

The influence of these toll-barriers extended far beyond actual

reach of the Noshima Murakami. The merchants of the

port-city of Sakai brought suit before the ąuchi lords complaining

that the Noshima toll-barrier impinged on their rights to

levy duties on China trade ships. Taking advantage of

their warrior status, the Noshima launched a counter-suit.

In the resulting compromise, the Sakai merchants recognized

Murakami rights to assess tolls on ships other than those

from southern Ky˛sh˛ which were the traditional preserve of

Sakai merchants.65

Noshima's acquisition of rights to assess tolls on the China

trade exemplifies how through manipulation of patronage networks,

the operation of toll barriers and the performance of protection

duty, Inland Sea pirates maneuvered themselves into not only

domestic shipping routes, but overseas trade networks as well.

Song Hui Gyong wrote in 1420 that after a search of their

hold, the Kamagari pirates let them go in favor of waiting

for more potentially lucrative ships from the Ry˛ky˛'s due

in the Inland Sea soon.66

Sources for Japan's tally trade with Ming China record several

instances in which the Muromachi Bakufu had its military governors

arrange for Inland Sea pirates to provide protection for the

tally ships en route in the Inland Sea and as far as Tsushima.67

Pirates also accrued great profit by operating toll-barriers

for warring patrons wishing to blockade parts of the Inland

Sea from enemy shipping as M╗ri Terumoto authorized in 1579.68

In 1581, a ship carrying the Jesuits Luis Frois and Alessandro

Valignano fell afoul of the Noshima Murakami who had used

the pretext of the blockade to stop the Jesuits at their Shiwaku

toll barrier. The Jesuits managed to escape from Shiwaku

and headed for the capital. But in the end, the Noshima

Murakami pirate ships surrounded the Jesuits just outside

the port of Sakai and forced them to pay 150 cruzados in coins

to ransom goods and two initiates the Noshima had captured

in the ensuing chaos.69

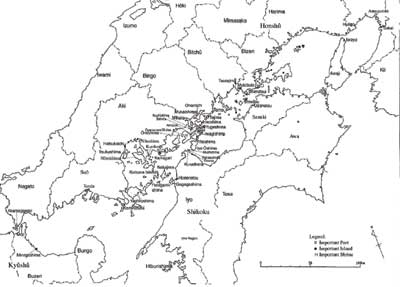

The Noshima Murakami pirates extended their formal and informal

domains to the extent that it became unnecessary for them

to send actual ships or pirates to accompany those vessels

paying for protection-duty at toll barriers. Beginning

in the 1560's and continuing through the mid-1580's, the Noshima

Murakami arrogated unto themselves what had previously been

a privilege reserved for the Imperial Court and warrior governments—the

issuance of passes of safe-conduct through the Seto Inland

Sea rendering the recipient immune from any further toll barriers.

In place of their members actually performing protection-duty

or escorting ships, the Noshima Murakami sold pennants with

their family seal emblazoned in the center (figure 1).70

Recipients would fly the flags at their mastheads to make

it clear to any ship that the bearer sailed under the paid

protection of the Noshima Murakami kaizoku and was

immune from any further toll barrier or other piratical interference

in the Noshima domain.

It is impossible to determine the prevalence of the passes,

but from the eight extant examples, recipients of these flags

hailed from all ends of the Inland Sea. Occupations

of those known to have received the flags run the full gamut

of maritime activities. The Noshima bestowed passes

upon other maritime lords such as the Mats˛ra of Hizen beyond

the Inland Sea in northwest Ky˛sh˛,71 harbor officials from the gates of the Inland

Sea at Akamagaseki as well as ports in Ky˛sh˛, the important

religious and commercial center of Itsukushima, shipping organizations

from Kii province, and travelers seeking safe passage such

as Jesuits. All of these parties recognized that without

the favor of the Noshima pirates, safe passage across the

Inland Sea was impossible. Unlike intercepting ships at toll

barriers and extracting payment with threat of force, the

Noshima often granted flags at the request of the party seeking

safe passage.72

In 1586, even after Toyotomi Hideyoshi had pacified much of

Japan, Luis Frois recorded that a Noshima flag-pass was required

in order to pass unmolested through the Inland Sea.

The Jesuits sailed to Noshima and dispatched a Japanese member

of their group to ask for Noshima Murakami Takeyoshi's good

will and a pass of safe passage. Takeyoshi inquired

as to why they needed a pass if they had already obtained

the goodwill of the hegemon Hideyoshi. The messenger

repeated on the Jesuit's behalf that only Takeyoshi could

protect them on the sea (perhaps the Jesuits also wished to

avoid an embarrassment as befell them in 1581). Takeyoshi

acquiesced and bestowed upon them a silk pennant bearing his

family's crest. If they encountered a suspicious ship,

the Jesuits could pass safely by simply showing the flag.73 On the waterways of the

Inland Sea, Takeyoshi's authority transcended that of the

hegemon Hideyoshi; only the Noshima pirates could guarantee

the safety of any ship.

These flags represent the apex of the Noshima Murakami's informal

piratical domain, the reach of their reputation and influence.

Taking advantage of the sheer punitive force at their disposal,

their wide-ranging formal domain, and the networks of sea-people

created through the administration of maritime labor and commerce,

the Noshima Murakami made the promises of the flags a reality.

Potential travelers sought out the Noshima Murakami to ensure

safe passage, inherently recognizing Noshima pirate suzerainty

over the Inland Sea. The issuance of these safe-passage

flags also gave the Noshima Murakami legitimacy to their own

toll-barriers by equating them with legitimizing institutions

powerful in past ages such as the Imperial court and warrior

government.

Sea routes converging on the Japanese archipelago brought

Japanese, Jesuit, and Korean travelers who wrote accounts

relating similar experiences: being forced by pirates to stop

and pay a toll to accept their protection to ensure a safe

journey across the Inland Sea. Regardless of whether

or not pirates operated with or without the sanction of elite

landed institutions, to travel the sea-road from the capital

to Ky˛sh˛ and back again required dealing with pirates. Completion

of unification by Hideyoshi required the eradication of such

independent sea-based power. Only by physically removing

kaizoku from their castle-bases on the sea-lanes and

moving them to holdings in inland regions did Hideyoshi finally

end the power of pirates.74

Piratical sea-tenure defined maritime space with nodes of

fortified islands, toll barriers, ports, and seaside villages

that connected webs of sea-lanes and networks of markets and

sea-peoples. Recognized as local elite warriors, kaizoku

leaders incorporated less powerful pirate organizations and

fishing villages into their realm and pirate bands and administered

them by dispatching agents, issuing law codes, levying taxes,

and managing commercial interactions. Pirate overlords

administered shipping organizations, harbormasters, and other

maritime labor, coming to control much of the shipping of

the Inland Sea. The operation of toll barriers and performance

of protection-duty defined the extent of the pirates' formal

and informal domains. Among the Murakami houses, the

Noshima branch grew to become the most adept at negotiating

the continuums of patronage and brigandage until they acquired

a reputation for being the most powerful pirate band of the

Inland Sea. Through their formal and informal domains and

participation in patronage networks, pirates were an integral

part of the maritime systems linking the sixteenth-century

East Asian world.

|

|

| |

|

Murakami Takeyoshi flag-pass ("Murakami Takeyoshi

kashoki") privately owned in the holdings of the

Yamaguchi Prefectural Archive (Yamaguchi-ken Monjokan)

and used with their permission.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

The Seto Inland Sea in the Medieval Period (Adapted

from Hy╗go Kitanoseki irifune osamech╗, 260-261).

|

|

|

|

Notes

1

"Luis Frois shokan," 16-17th c. Iezusukai Nihon h╗kokush˛,

3rd period, vol. 7, ed. trans. Matsuda Kiichi, (Tokyo: D╗b╗sha

Shuppan, 1994), 140-141.

2

The term Seto Inland Sea or any other name for any ocean does

not appear in extant documents of premodern Japan. However,

for clarity's sake, I hope the reader will permit this anachronistic

usage. I am also interested in the implications this

namelessness has for the study of maritime space in premodern

Japan.

3

Examples of pirates accepting the sponsorship of landed powers

are common around the world in the premodern and early modern

periods. Examples range from the responses of Korea's

Choson Dynasty and China's Ming Dynasty to thewak╗,

Qing China to the pirates of Cheng I and Cheng I Sao, to Queen

Elizabeth and her privateers, to the Caribbean of Captain

Morgan, to the corsairs of the Mediterranean.

Thinking of warriors as participating within a continuum of

service and not a binary of loyalty-disloyalty comes from

Tom Conlan, "Largesse and the Limits of Loyalty in the Fourteenth

Century," in Jeffrey Mass ed. The Origins of Japan's

Medieval World, (Stanford: Stanford U. Press, 1997), 39-64.

4

For a good overview of the different categories of usage for

kaizoku, see Sakurai Eiji, "Sanzoku, kaizoku to

seki no kigen," In Amino Yoshihiko ed. "Shokunin"

to "Gein╗", (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1994),

113-148

5

Udagawa Takehisa, Setouchi suigun, (Ky╗ikusha, 1980),

58.

6

"M╗ri Terumoto shoj╗," Ehime kenshi shiry╗hen, kodai ch˛sei,

ed. Ehime Kenshi Hensan Iinkai, (Matsuyama: Ehime Pref.,

1983), #2365. (Hereafter, EK#_, "title").

7

In the late sixteenth century, the branches of the Murakami

family exchanged signed oaths with the M╗ri. . See EK

#2102 "Murakami Takeyoshi kish╗mon;" EK #2103 "M╗ri

Motonari, Kobayakawa Takakage, M╗ri Terumoto rensho kish╗mon."

By 1582, the M╗ri so desired to retain the services of the

Noshima pirates that the M╗ri repeatedly swore holy oaths

to respect Noshima concerns to the extent possible.

8

The interaction of the branches of the Murakami family and

the salt-producing island sh╗en of Yugeshima exemplify

this cycle. Agents of the proprietor T╗ji would negotiate

with one band to subdue another band, but before long, the

first pirate band would require suppression as well.

See for example, "Yugeshima no sho monjo-an," Nihon engy╗

taikei, shiry╗-hen, kodai-ch˛sei 1, ed.

Nihon Engy╗ Taikei Hensh˛ Iinkai, (Tokyo: Bunkasha,

1982), #291; #295"T╗ji zassh╗ m╗shij╗ no an;" #230 "Gon

no Risshi K╗ga Yugeshima no sh╗ Kujirah╗ shomushiki ukebumi,"

9

Fujiki Hisashi, Z╗hy╗tachi no senj╗, (Asahi Shimbunsha,

1995).

10

EK #2037 "M╗ri Motonai shoj╗." For further

interpretation of this document and political marriages between

the M╗ri and families in Iyo, see Nishio Kazumi, "Sengoku

makki ni okeru M╗ri-shi no kon'in kankei to Iyo," Nihonshi

kenky˛, 445 (1999:9), 1-29.

11

EK #2119 "Kobayakawa Takakage shoj╗."

12 Most famously Udagawa Takehisa

in his Setouchi suigun (Tokyo: Ky╗ikusha, 1980).

13

See Sakurai, 1994; Much of my understanding of pirates as

sea-peoples comes from Amino's work. His classic account

is in "Kaimin no shomibun to sono y╗s╗," In Nihon

ch˛sei no hin╗gy╗min to Tenn╗, (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten,

1984), 240-281. For a more recent treatment, Kaimin

to Nihon shakai, (Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu ąraisha, 1998).

For summaries in English, see Rereading Japanese History,

trans. Alan Christy (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press, forthcoming).

14 Many of these ideas are inspired

by Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell, The Corrupting

Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History, (Oxford; Malden,

MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000).

15

In 1562, the Noshima lord Takeyoshi argued that an inland

territory bore insufficient appeal to compensate the Noshima

pirates for their activities. See EK, #1900 "M╗ri Motonari

shoj╗."

16

This difference is epitomized in the reaction of the peripatetic

poet S╗gi to sea-peoples as he crossed to Ky˛sh˛ in 1480 and

expressed amazement that the sea-peoples calmly and deftly

operated their tiny fishing craft despite pitching waves that

had land-travelers clutching each other in fear. See

S╗gi, "Tsukushi no michi no ki," Ch˛sei nikki kik╗sh˛,

Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei 51, (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten,

1990), 411. Further depictions of sea-people as weapons-bearing

fisherfolk can be found in medieval tales (like Konjaku

monogatari-sh˛). Travel narratives from Ki no Tsurayuki's

tenth century Tosa nikki (NKBT vol. 20) to records

of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu's pilgrimage to Itskushima ("Rokuon'in

saigoku gek╗ki," to Shimazu Iehisa's journey to the capital

in the late sixteenth-century ("Ch˛sho Iehisa-k╗ onj╗ky╗ nikki."The

last two are in, Shint╗ taikei bungaku hen vol. 5 sankeiki)

depict themes like the helpless reliance of landed

elites on the captains and sailors who carry them as well

as the alien rhythms and jargons of seafarers.

17

See documents cited in Kishida Hiroshi, Daimy╗ ry╗koku

no keizai k╗z╗, (Iwanami Shoten, 2001), 198.

18

Yamauchi Yuzuru, Kaizoku to umijiro, (Tokyo: Heibonsha,

1997), 31.

19

Yamauchi, 1997, 24-26.

20 For example, see "Tokui

Michiyuki shoj╗," Ehime kenshi shiry╗hen kodai ch˛sei,

Ehime Kenshi Hensan Iinkai, ed. (Matsuyama: Ehime Pref.,

1983), #2241. (Hereafter EK #_, "title.") For more on

the atakebune [ ],

see Ishii Kenji, Wasen II, Mono to ningen no bunkashi 76-II,

(Tokyo: H╗sei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1995). ],

see Ishii Kenji, Wasen II, Mono to ningen no bunkashi 76-II,

(Tokyo: H╗sei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1995).

21

For an example of how pirates incorporated seafarers into

their pirate bands, see EK#1713 "Shirai Fusatane Teoi ch˛mon

narabi ni ąuchi Yoshitaka sh╗han." The word kako

(sailor) is a profession-specific term used in conjunction

with the word bokuj˛ (conscript) describing sailors

without surnames indicating that pirates drew sailors of different

status groups into their bands.

22

See for example, EK #1906 Murakami Michiyasu andoj╗ from 1563

for the Nomi family of Nomishima.

23

Yamaguchi kenshi, shiry╗-hen ch˛sei 2

(Yamaguchi Pref:, 2001), 116, "Toshinari-ke monjo," #2-3.

24

EK #2302 "Murakami Motoyoshi okitegaki."

25

EK #2365 "M╗ri Terumoto shoj╗."

26

EK #2053 "Kodama Narikata shoj╗."

27

EK #2176 "Kobayakawa Takakage shoj╗."

28

See a letter from 1574 in which Noshima Murakami Takemitsu

issues instructions to the Sak╗ family of harbor-masters in

Akamagaseki (today's Shimonoseki). Quoted in Kishida Hiroshi,

Daimy╗ ry╗koku no keizai k╗z╗. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten,

2001), 198.

29

The island is also famous as a legendary base of the 10th

c. pirate leader Fujiwara no Sumitomo.

31

EK #2194, "Hokkenotsu Han'en okitegaki"

32

Traditionally in the medieval period, items that washed ashore

became the property of the local lord, especially valuable

objects like whale carcasses (cf Morimoto Masahiro, "GoH╗j╗-Shi

no suisanbutsu j╗n╗sei no tenkai," Nihonshi kenky˛

359, no. 7 (1992): 33).

33

A large number of these documents are published in Amino Yoshihiko,

"Iyo no kuni Futagamishima wo megutteŃFutagami-shi to Futagami

monjo," Nihon ch˛sei shiry╗gaku no kadai, (Tokyo: K╗bund╗,

1996), 250-282 (documents will be cited hereafter as Amino-Futagami,

#).

35

EK, #1577. The first extant holding-confirmation order

from the Kurushima for Futagami dates from 1506. See EK, #1596.

Also see Amino-Futagami, #46.

36

Amino-Futagami, #40, 41, 48.

39

EK #1732 "Murakami Michiyasu shoj╗."

40

EK #2245 "Futagami Yasutane shoj╗."

41 Morimoto Masahiro, "GoH╗j╗-shi

no suisanbutsu j╗n╗sei no tenkai," Nihonshi kenky˛

359, no. 7 (1992): 33-35.

42

Amino Yoshihiko, Kaimin to Nihon shakai, (Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu

ąraisha, 1998), 38.

44

EK, #2239 "Tokui Michiyuki shoj╗."

45

EK #2302 "Murakami Motoyoshi Okitegaki."

46

EK, #2440 "Futagami-shi monjo an."

47

EK #1713 "Shirai Fusatane teoi ch˛mon narabi ni ąuchi

Yoshitaka ch╗han."

49

Luis Frois, "Luis Frois shokan, 1588, 2/20," 16-17th c.

Iezusukai Nihon h╗kokush˛, 3rd period, vol. 7, ed. trans.

Matsuda Kiichi, (Tokyo: D╗b╗sha Shuppan, 1994), 172.

50 EK #1663. Hosokawa Takakuni and ąuchi Yoshitaka

were fighting on behalf of their shogunal candidates.

In EK #1665, ątomo Yoshiaki writes that as part of this anti-ąuchi

coalition, K╗no Michinao and Murakami Kunnaitaifu [Takashige,

thought to be Takeyoshi's father] were responsible for maritime

concerns. In exchange for that service, Takakuni granted

them their holding on Shiwaku.

51

EK, #1996. Letter from M╗ri Motonari to Noshima Murakami Motoyoshi

52

EK #2087 "ątomo S╗rin shoj╗."

53

EK #2086 "Murakami Takeyoshi shoj╗."

54

The term kaisen ( )

refers to the transport of goods while binsen ( )

refers to the transport of goods while binsen ( )

refers to passengers. )

refers to passengers.

55

EK #2053 "Kodama Narikata shoj╗."

56

Quoted in Kishida Hiroshi, Daimy╗ ry╗koku no keizai k╗z╗,

(Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2001), 198.

58 Sakurai, 116-119. Sakurai

suggests that as the principal method of extracting wealth

for pirates was by charging tolls to passing ships, perhaps

pirates emerged from sea-peoples whose duties included collecting

maritime produce for religious institutions. Over time

this practice transformed into charging tolls for safe passage.

59

Reisen ( ).

The monk Bairin Shury˛ recorded this incident in

his travelogue of a trip to and from the province of Su╗ in

1550. See "Bairin Shury˛ Su╗ gek╗ nikki," in Yamaguchi

kenshi, ch˛sei shiry╗-hen vol. 1 (Yamaguchi Pref.,

2000), 471 ).

The monk Bairin Shury˛ recorded this incident in

his travelogue of a trip to and from the province of Su╗ in

1550. See "Bairin Shury˛ Su╗ gek╗ nikki," in Yamaguchi

kenshi, ch˛sei shiry╗-hen vol. 1 (Yamaguchi Pref.,

2000), 471

60

Horden and Purcell, 157.

61

Aida Nir╗, Ch˛sei no sekisho, (Yoshikawa K╗bunkan,

1976 reprint (originally published 1943), 1-14.

62

Song, Hui-Gyong, Nosongdang Ilbon Haegnok (R╗sh╗d╗ Nihon

K╗roku), ed. Murai Sh╗suke, (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1987),

#162. Hereafter, RNK, _.

64

EK #1519, "Murakami Yoshimitsu Yuzurij╗."

65

EK #1730 "ąuchi-shi bugy╗nin rensho h╗sho." In 1540,

ąuchi dispatched pirates to attack northern Iyo to try and

capture the sea-lanes by force. The K╗no called on the

Murakami pirates to help defend Iyo. Although pirates

under K╗no patronage beat off the attacks, the acquisition

of Noshima's services was a significant gain for the ąuchi.

For an example of the conflict, see EK, #1713.

67 See for example, Manzai jug╗

nikki (Tokyo: Zokugunshoruij˛, hoi 1, 1958), vol.

2, 547 (1434, (Eiky╗ 6), 1/20). Also "Boshi ny˛minki,"

In Sakugen ny˛minki no kenky˛, vol.1 ed. Teiry╗ Makita,

(Kyoto: Matsuzaki Insatsu Kabushiki Gaisha, 1955), 351-364.

68

Hagi-han batsuetsuroku, Nagata Masazumi ed. (Yamaguchi:

Yamaguchi-ken monjokan, 1967), vol. 3:135, 840, #15, 842,

#30.

69

"Luis Frois shokan," 16-17th c. Iezusukai Nihon h╗kokush˛,

3rd period, vol. 5, ed. trans. Matsuda Kiichi, (Tokyo: D╗b╗sha

Shuppan, 1992), 286-287.

70

A complete description of most of the extant records of these

pennants can be found in a pair of articles by Takahashi Osamu,

"Shinshutsu no 'Murakami Takeyoshi kashoki," Wakayama kenritsu

hakubutsukan kenky˛ kiy╗ 4 (3/1999) 41-52; 5 (3/2000),

32-41. The flag in Figure 1 is woven from hemp (52.6 cm tall

x 42.3 cm wide) and has the Murakami house mark in the center

in black ink. The recipient (in this case Sh˛shi of Itsukushima)

is written on the right and the date of issue on the left

(9th year of Tensh╗ [1581], 4/28) followed by the signature

of the issuer (Noshima Murakami Takeyoshi). For the Itsukushima

flag in particular, see Kanaya Masato, Kaizokutachi no

ch˛sei, (Tokyo: Yoshikawa K╗bunkan, 1998), 65.

71

This example comes not from Takahashi but from Kishida,

2001, 348, the rest can be found in Takahashi (1999).

72

See a document quoted in Kishida, 2001, 198 in which the Noshima

Murakami approved a request by the Sak╗ family, harbor-masters

for Akamagaseki, for a flag-pass. Cf. The request from

the Jesuits included below.

73

"Luis Frois no Indo Kankuch╗ Alessandro Valignano-ate shokan,"

16-17th c. Iezusukai Nihon h╗kokush˛, 3rd period, vol.

7, ed. trans. Matsuda Kiichi, (Tokyo: D╗b╗sha Shuppan, 1994),

141.

74

Yamauchi Yuzuru, Ch˛sei Setonaikai chiikishi no kenky˛,

(Tokyo: H╗sei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1998), 190-191.

|

Copyright Statement

Copyright: ę 2003 by the American Historical

Association. Compiled by Debbie Ann Doyle and Brandon Schneider. Format

by Chris Hale.

|

![]() ],

see Ishii Kenji, Wasen II, Mono to ningen no bunkashi 76-II,

(Tokyo: H╗sei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1995).

],

see Ishii Kenji, Wasen II, Mono to ningen no bunkashi 76-II,

(Tokyo: H╗sei Daigaku Shuppankyoku, 1995).

![]() ,

harborŃtomari

,

harborŃtomari ![]() .

Production district—my╗

.

Production district—my╗ ![]() .

It is important to note that although these sites bear the

suffix harbor or bay, the name refers to the land defined

by the maritime function and not the oceanic space itself.

.

It is important to note that although these sites bear the

suffix harbor or bay, the name refers to the land defined

by the maritime function and not the oceanic space itself.

![]() )

refers to the transport of goods while binsen (

)

refers to the transport of goods while binsen (![]() )

refers to passengers.

)

refers to passengers. ![]() ).

The monk Bairin Shury˛ recorded this incident in

his travelogue of a trip to and from the province of Su╗ in

1550. See "Bairin Shury˛ Su╗ gek╗ nikki," in Yamaguchi

kenshi, ch˛sei shiry╗-hen vol. 1 (Yamaguchi Pref.,

2000), 471

).

The monk Bairin Shury˛ recorded this incident in

his travelogue of a trip to and from the province of Su╗ in

1550. See "Bairin Shury˛ Su╗ gek╗ nikki," in Yamaguchi

kenshi, ch˛sei shiry╗-hen vol. 1 (Yamaguchi Pref.,

2000), 471