In 1882, William Hulbert died and Albert Goodwill Spalding took over both the White Stockings and Hulbert's influence over the National League. He would prove to be baseball's answer to Vanderbilt, Carnegie, and Rockefeller.

In 1882, William Hulbert died and Albert Goodwill Spalding took over both the White Stockings and Hulbert's influence over the National League. He would prove to be baseball's answer to Vanderbilt, Carnegie, and Rockefeller.

Spalding was a great pitcher in his own right, being the first professional ever to win 200 games. He had led Boston to their four consecutive National Association titles before coming to Chicago in Hulbert's contractural coup on 1876. Hulbert's  offer was a $500 raise and the promise of a quarter of the White Stockings' gate -- an informed decision, as Spalding won 47 games that year to deliver Hulbert the inaugural NL title. However, just after the start of the 1877 season, Spalding stopped pitching to become a full-time promoter and businessman.

offer was a $500 raise and the promise of a quarter of the White Stockings' gate -- an informed decision, as Spalding won 47 games that year to deliver Hulbert the inaugural NL title. However, just after the start of the 1877 season, Spalding stopped pitching to become a full-time promoter and businessman.

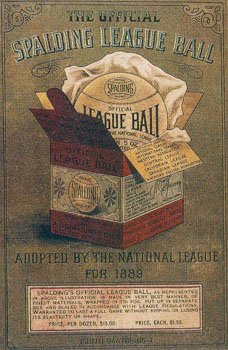

He opened a sporting goods business, with an $800 loan from his mother, which got its start by manufacturing baseballs. Spalding paid the National League to use his balls, so that he might advertise them as the "offical" league ball. Soon, his comapny was making golf clubs, tennis rackets, basketballs, and anything else remotely connected to sport. Advanced by his enterprise, "Americans are evoluting into a fresh-air people. They are being converted to the gospel of exercise," Spalding claimed.1

The Boston Herald shared Spalding's high opinion of himself:

Next to Abraham Lincoln and George Washington, the name of A.G. Spalding is the most famous in American literature. It has been blazing forth on the cover of guides to all sorts of sports, upon bats and gloves. . . for many years. Young America gets its knowledge of the past in the world of athletics from something that has "Al Spalding" on it in big black letters, and for that reason, as much as any other, he is one of the national figures of our times.2

Much of Spalding's business success relied on his visibility in the baseball world, both as a player and an administrator. Besides producing the official league ball, Spalding and Bros. also had the exclusive contract for the "official league book" which outlined the game's rules and regulations. Opportunistically, he then supplemented this with an annual, Spalding's Official Baseball Guide, which, in spite of its title, was not an official league publication. The Guide included overviews of the preceding season, records, coaching, and eventually editorials consistent with Spalding's opinions on the game and its development. It was a powerful instrument in shaping public thought on baseball and the role of ownership and order. It also proved to be a useful advertising vehicle, as its pages were resplendent with advertisements for Spalding's extensive line of sporting goods.

Much of Spalding's business success relied on his visibility in the baseball world, both as a player and an administrator. Besides producing the official league ball, Spalding and Bros. also had the exclusive contract for the "official league book" which outlined the game's rules and regulations. Opportunistically, he then supplemented this with an annual, Spalding's Official Baseball Guide, which, in spite of its title, was not an official league publication. The Guide included overviews of the preceding season, records, coaching, and eventually editorials consistent with Spalding's opinions on the game and its development. It was a powerful instrument in shaping public thought on baseball and the role of ownership and order. It also proved to be a useful advertising vehicle, as its pages were resplendent with advertisements for Spalding's extensive line of sporting goods.

Spalding's veiled pedagogy extended into his Library of American Sports series. Beginning as a thirteen volume series in 1885, the Library was reorganized as Spalding's Athletic Library, consisting of 300 separate publications on sport and physical activity -- "the greatest educational series on athletic and physical training subjects that has ever been compiled,"3 according to the Spalding-owned Official Guide of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues.

With the rise of department stores in the 1870s and 80s, "buyers of goods learned new roles for themselves, apprehended themselves as consumers." These stores were places "of learning as well as buying: a pedagaogy of modernity."4 Spalding managed to achieve a sort of virtual department store through his saturation of the sporting market -- from League administration, to League image, to the everyman amateur who absorbed it all. People were given an ordered product, taught how to view it, and how to incorporate it into their daily lives. Like other captains of industry at the time, Spalding vertically integrated his sphere, bullying, undermining, crushing, and sometimes conciliating with his competition.

Spalding later defined his Darwinistic attitude: "the magnate must be a strong man among strong men. Everything is possible to him who dares."5

1 Peter Levine, A.G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball (New York: Oxford UP, 1985) 83.

2 Levine 89.

3 Levine 82.

4 Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982) 130-1.

5 Geoffrey C. Ward, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Knopf, 1994) 29.

A.G. Spalding

A.G. Spalding

A.G. Spalding

A.G. Spalding