Uneeda-lot of... [brand name here]:

Early newspaper or journal advertisements looked essentially like want-ads. Type tended to be simple, of uniform size, and there were few if any illustrations. Besides these physical characteristics, early ads had a basic function: to inform consumers about a product's availability, cost, and character. The quantity of ads was also very low relative to what would come later: in the early 1870s magazines like Harper's Weekly and Leslie's Illustrated Weekly Newspaper would contain only 4 or 5 pages of ads that stayed separate from the content of the magazine, usually in the back. The advertising found therein was relatively simple and was geared to markets for which demand already existed without much appeal to class, status, or to increased consumption.1 Many businesses actually shied away from only the most basic type of ads. Making outrageous claims was the hallmark of the patent medicine industry and was not looked upon favorably.

A New Crop of Magazines

Technological improvements in the last two decades of the century allowed for faster and lower cost printing; this combined with reduced paper prices, favorable postage rates, and new advertising dollars favored a wider and larger distribution of low-cost popular newspapers, magazines, and journals.3 While older, more established literary magazines hesitated to incorporate all but the most limited advertising into their serious minded output, in the 1880s a new crop of magazines emerged whose outright objective was to make their money from advertising. These magazines, in particular Ladies' Home Journal, McClure's, Cosmopolitan and Munsey's, catered their content toward the growing urban middle class, the class with the money to buy the goods being advertised.4 Each issue of Ladies' Home Journal contained articles of interest to middle class women: "advice on how to dress, cook, feed their families, decorate their homes, care for their health, and raise their children." 5 Of course, there were stories by popular writers like Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle and Mark Twain. But as Cyrus Curtis said, explaining to an audience of manufacturers why he published the LHJ:

The editor thinks it is for the benefit of American women. That is an illusion, but a very proper one for him to have. But I will tell you; the real reason, the publisher's reason, is to give you people who manufacture things that American women want and buy a chance to tell them about your products. 6

And tell them they did. By the turn of the century advertising in popular magazines often exceeded a hundred pages an issue.

It comes as no surprise then that as advertising became more accepted, advertising itself became its own industry with its own scientific methods and cost benefit analysis. In time, advertising agencies would use the ads they created for clients to promote themselves and their proven sales abilities. As early as 1888, there was a trade magazine for advertisers (Printer's Ink) - and by the turn of the century there would be a dozen more7 - as well as countless manuals and guides to making the most effective ads.

And tell them they did. By the turn of the century advertising in popular magazines often exceeded a hundred pages an issue.

It comes as no surprise then that as advertising became more accepted, advertising itself became its own industry with its own scientific methods and cost benefit analysis. In time, advertising agencies would use the ads they created for clients to promote themselves and their proven sales abilities. As early as 1888, there was a trade magazine for advertisers (Printer's Ink) - and by the turn of the century there would be a dozen more7 - as well as countless manuals and guides to making the most effective ads.

Creating The Familiar:

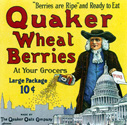

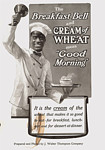

With more and more products on the market, companies worked to familiarize and humanize their relations with their customers. Through advertising campaigns and carefully designed packaging, distant manufacturers made themselves seem like they were right next door, or at least, friendly and familiar. Uniform packaging helped in this process of 'recognition', as did a brand name, a trademark or logo, and a catchy phrase or slogan. Using these techniques, companies created identities for their products, identities to which the consumer would hopefully attach so that no matter how many brands of soap or soup appeared on the shelf of the store, that consumer would choose the one that they knew, the one with which they identified. Ivory soap's 99 44/100% purity with the "It Floats" slogan was trademarked in 1891 and is still in use today. Other products used a character to breed familiarity, notably the Quaker Oats Quaker, Rastus the Cream of Wheat Chef, the Hire's Root Beer owl and Aunt Jemimah. The longevity of these trademark characters and the products that they represent is not coincidental; they function as part of the family, familiar and friendly faces at the table. An additional popular and popularizing practice was to claim that a product was 'sold by all good grocers' or 'sold everywhere'. If an item wasn't found in your store, your store wasn't good enough.

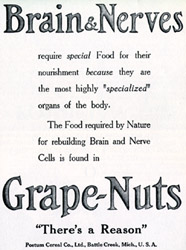

The Products Speak: The advertisements in these new magazines were designed to appeal to the middle class and to those aspiring to it. This involved defining that class, that is, creating a middle class agenda that involved the proper way to entertain, the proper way to clean, and the proper roles for a civilized woman, man and family. Many advertisements for food and household products played on anxieties about being a good wife and mother; Others targeted a product's time saving qualities and scientifically proven health benefits. Guilt was (and is) an effective tool: guilty if the sink was dirty, guilty if the children wore dirty clothes, guilty if they didn't eat right. Another way to influence the kitchen was on the pages of cookbooks. Many brands offered pretty books full of recipes, household advice, and maybe even a story or two. The cookbooks employed the same methods of suggestion as other advertisements: appeals to class and social status, to an item's popularity, to time saving or health benefits.

The advertisements in these new magazines were designed to appeal to the middle class and to those aspiring to it. This involved defining that class, that is, creating a middle class agenda that involved the proper way to entertain, the proper way to clean, and the proper roles for a civilized woman, man and family. Many advertisements for food and household products played on anxieties about being a good wife and mother; Others targeted a product's time saving qualities and scientifically proven health benefits. Guilt was (and is) an effective tool: guilty if the sink was dirty, guilty if the children wore dirty clothes, guilty if they didn't eat right. Another way to influence the kitchen was on the pages of cookbooks. Many brands offered pretty books full of recipes, household advice, and maybe even a story or two. The cookbooks employed the same methods of suggestion as other advertisements: appeals to class and social status, to an item's popularity, to time saving or health benefits.

1 James D. Norris, Advertising and the Transformation of American Society, 1865-1920 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1990), p. 26.

2 http://aef.harpweek.com/

3 Norris, 31.

4 Ibid., 35.

5 Ibid., 36.

6 Ibid., 36.

7 Ibid., 42.