From Factory To Kitchen:

On The Rails:

Until 1850 canal boats had carried most of the country's freight, including food; but railroads replaced canals within 25 years of their first appearance in 1826. As the railroad network developed, factories and mills sprouted up along its routes; the railroad in turn carried factory-made goods across the country. From now on, the point of production had no necessary connection to the point of sale.

tenderer, because cattle which rode to market instead of walking to it did not develop such tough muscles; tastier, because the same lines that carried cattle north and east also carried grain with which to fatten them south and west; cheaper because they lost less weight between pasture and slaughterhouse. 1

Eventually the cattle wouldn't make that ride - not alive anyway. After The Civil War, many cities banished the slaughterhouses that existed within their limits, sometimes  in residential districts. The unsanitary conditions, the blood and the stench, would no longer be tolerated, much to the dismay of local butchers who were losing their time-honored tradition. Two Chicago meat entrepreneurs, however, worked to handle this problem and in so doing, sealed the national meat market. Gustavus Franklin Swift and Philip Danforth Armour followed a parallel course in convincing a railroad line to move their already processed meat on refrigerated cars that they would build themselves. Now the cattle could be slaughtered in the centralized and efficient processing system of Chicago and be shipped as chilly carcasses to eastern and other markets. 2

in residential districts. The unsanitary conditions, the blood and the stench, would no longer be tolerated, much to the dismay of local butchers who were losing their time-honored tradition. Two Chicago meat entrepreneurs, however, worked to handle this problem and in so doing, sealed the national meat market. Gustavus Franklin Swift and Philip Danforth Armour followed a parallel course in convincing a railroad line to move their already processed meat on refrigerated cars that they would build themselves. Now the cattle could be slaughtered in the centralized and efficient processing system of Chicago and be shipped as chilly carcasses to eastern and other markets. 2

In The Factory:

Early canning involved tinsmiths joining together the 3 components of a can: the long strip comprising the body of the can and the top and the bottom. The parts were cut and soldered by hand and two skilled tinsmiths could turn out just 120 cans a day. Improvements in this process by the 1840s allowed two unskilled men to turn out 1,500 a day. Just before The Civil War, the output of processing for various foods was 5 million cans a year; by 1870, the nation was consuming 30 million cans a year. The war had created not only a huge military demand for canned food, but also created soldiers who, after the war had ended, insisted that their wives feed them the canned food they had grown used to eating.3 Continued progress in canning technology maintained the frenetic pace: in 1876, a machine was invented through which long lines of cans flowed continuously for automatic sealing and by 1880 the manufacturing of cans was its own industry.

By the end of the century, the United States was producing about half of the total world production of preserved foods.4

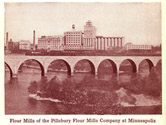

Flour processing was also changing around the time of the Civil War. A shift towards white flour had begun in the 1840s when the Hungarians (leaders in flour technology) replaced rotary millstones with rollers in their flour mills. The rollers squeezed the inner part of the wheat kernel from its coating, in effect getting rid of both the bran and the germ. Bakers liked this elimination because wheat germ, while nutritious, contains oil which makes the flour go bad in just a few weeks. The shift to white flour was sealed in 1870 when the Hungarians started to use porcelain flour mill rollers, producing the finest, whitest, and most longlasting flour yet. By 1881, all of the mills in Minneapolis were using porcelain rollers.5

Interestingly, this process of getting rid of the bran led to a problem at the Pillsbury plant - and to a solution. In the past excess bran had been dumped into the Mississippi, no use having been found for it. With the increase in flour production and the consequent increase in bran waste, the bran problem was "acute". The idea was hatched to experiment with feeding the bran to 15 scrub steers to see if they would like it. Like it they did, even becoming agitated when the bran ran out one day. Whatsmore, and more importantly, the bran-fed beef wasn't bad either. In 1892, Pillsbury sent out its first shipment - 6 carloads - of commercial feed. 6

In The Store:

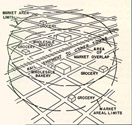

The development of what are now day-to-day items like paper bags and cardboard boxes changed the way that food was transported, both from the factory to the store and from the store to the kitchen. Until the paper bag, purchaser's carried their own containers to grocers to carry things home. After 1870, when the process to make the paper bag was patented, purchasers could fill up innumerable sacks with impulse purchases. This did not change the fundamental relationship between the grocer and purchaser, however, it just increased sales. The grocer still bought goods in bulk and sold different amounts according to customer need or desire. It was the development of the cardboard box that would make mass marketing of goods possible.7

Once the process to mass produce cardboard boxes was developed in 1879, goods could be placed directly in cardboard boxes and shipped as units to the stores to be sold. Cardboard boxes were sturdy, stackable, and sanitary. The pioneers of mass production discovered another benefit to cardboard: it was sturdy enough to print a brand name and a logo right on it. In 1899, the In-er-seal carton was patented and The National Biscuit Company started to ship out their products in small, individual units for customers. Each little box was like a commercial for the product, for the company, for the company's cleanliness, trustworthiness. "The ability to create a totally packaged object - sealed, branded, and only opened after it had reached the consumers home - closed the circle of bulk retailing... by eliminating the middleman." 8

Once the process to mass produce cardboard boxes was developed in 1879, goods could be placed directly in cardboard boxes and shipped as units to the stores to be sold. Cardboard boxes were sturdy, stackable, and sanitary. The pioneers of mass production discovered another benefit to cardboard: it was sturdy enough to print a brand name and a logo right on it. In 1899, the In-er-seal carton was patented and The National Biscuit Company started to ship out their products in small, individual units for customers. Each little box was like a commercial for the product, for the company, for the company's cleanliness, trustworthiness. "The ability to create a totally packaged object - sealed, branded, and only opened after it had reached the consumers home - closed the circle of bulk retailing... by eliminating the middleman." 8

In The Kitchen:

While advertisements for cookstoves began to appear in the early part of the century, it wasn't until the 1850s that they were in widespread use (many models were inefficient or difficult to use however). Indeed, by mid-century hundreds of founderies were turning out ranges and cookstoves, so rapidly in fact, that a stove could become outdated in a year or two due to constant improvements in stove technology.9

The importance of the shift from hearth cooking to use of the range or cookstove cannot be overstated. This development altered American cookery methods and meal planning, while at the same time relieving the housewife or cook of multiple backbreaking chores such as lifting and moving heavy iron cookware. Perhaps most importantly, the introduction of the stove brought technology into the kitchen and as the century progressed, a continuous stream of updated and improved appliances became available.... 10

The stove not only allowed you to cook more things at once, it performed other functions that made life easier. On this ideal cooking stove with all possible attachments, you could "keep 17 gallons of water hot in the reservoir, bake pies in the warming closet, warm sadirons underneath the back cover, bake bread in the oven, roast meat in the tin roaster and make tea on a top burner or under the baking cover." 11 Hot water for washing, irons for ironing, and bread baking, all at the same time. Of course, this involved intensive management of dampers and the heat source, be it wood or coal. Management itself became an art form.

The stove not only allowed you to cook more things at once, it performed other functions that made life easier. On this ideal cooking stove with all possible attachments, you could "keep 17 gallons of water hot in the reservoir, bake pies in the warming closet, warm sadirons underneath the back cover, bake bread in the oven, roast meat in the tin roaster and make tea on a top burner or under the baking cover." 11 Hot water for washing, irons for ironing, and bread baking, all at the same time. Of course, this involved intensive management of dampers and the heat source, be it wood or coal. Management itself became an art form.

Cooking also became more of an art form and a profusion of gadgets sought to help the cook or housekeeper save time and energy in her tasks. Gadgets and utensils that had previously been handcrafted or hand-forged were now produced in bulk. Many were cast-iron or factory made wooden examples and most had clamps, turn-cranks or action gears. Mrs. F. L. Gillette's and Hugo Ziemann's 1887 White House Cookbook included a list of items found in a properly equipped kitchen. "An ingenious housewife will manage to do with less conveniences," the book explained, "but these articles, if they can be purchased in the commencement of housekeeping, will save time and labor, making the preparation of food more easy - and it is always economy in the end to get the best material in all wares..." 12

1 Waverly Root and Richard de Rochemont, Eating In America (Hopewell, NJ: The Ecco Press, 1995), p. 152.

2 Ibid., 209.

3 Ibid., 190.

4 Stuart Thorne, The History of Food Preservation (Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble Books, 1986), p. 18.

5 Root, 231.

6 Philip W. Pillsbury, The Pioneering Pillsburys (New Jersey: Princeton University Press for The Newcomen Publications, 1950), p. 19-20.

7 M.M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemimah (Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1998), p. 63.

8 Ibid., 64.

9 Ellen Plante, The American Kitchen 1700 to the Present (New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc., 1995). p. 43.

10 Ibid., 70.

11 Ibid., 43.

12 Ibid., 101.