D-Lib Magazine

July/August 2017

Volume 23, Number 7/8

Table of Contents

Trends in Digital Preservation Capacity and Practice: Results from the 2nd Bi-annual National Digital Stewardship Alliance Storage Survey

Michelle Gallinger1

Gallinger Consulting

mgallinger [at] gallingerconsult.com

Jefferson Bailey

Internet Archive

jefferson [at] archive.org

Karen Cariani

WGBH Media Library and Archives

karen_cariani [at] wgbh.org

Trevor Owens

Institute of Museum and Library Services

tjowens [at] imls.gov

Micah Altman

MIT Libraries

micah_altman [at] alumni.brown.edu

https://doi.org/10.1045/july2017-gallinger

Abstract

Research and practice in digital preservation requires a solid foundation of evidence of what is being protected and what practices are being used. The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) storage survey provides a rare opportunity to examine the practices of most major US memory institutions. The repeated, longitudinal design of the NDSA storage surveys offer a rare opportunity to more reliably detect trends within and among preservation institutions rather than the typical surveys of digital preservation, which are based on one-time measures and convenience (Internet-based) samples. The survey was conducted in 2011 and in 2013. The results from these surveys have revealed notable trends, including continuity of practice within organizations over time, growth rates of content exceeding predictions, shifts in content availability requirements, and limited adoption of best practices for interval fixity checking and the Trusted Digital Repositories (TDR) checklist. Responses from new memory organizations increased the variety of preservation practice reflected in the survey responses.

Keywords: Digital Preservation, Capacity, Practice, Storage, Fixity, National Digital Stewardship Alliance

1 Introduction

Preservation of digital content is conducted based on evidence of the most reliable storage, data management, and digital content lifecycle practices. As research and practice identify better preservation methods, organizations adjust their policies and workflow. The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) storage survey provides a significant window into the practices of many major US memory institutions. The NDSA storage survey was designed with longitudinal questions in order to more reliably detect trends within and among preservation institutions over time. This is different than the typical surveys of digital preservation, which are based on one-time measures and convenience (Internet-based) samples. NDSA members are universities, consortia, commercial businesses, professional associations, and government agencies dedicated to ensuring enduring access to digital information.

The NDSA Infrastructure Working Group sponsored the NDSA Storage Survey as a way to examine trends in preservation storage. The goal of the 2011 and 2013 surveys was to develop a snapshot of storage practices within the organizations of the NDSA and insight into how those practices change over time. This work is part of the group's larger effort to explore NDSA members' current approaches to large-scale storage systems for digital stewardship as well as the potential for cloud computing and storage in digital preservation. The storage surveys contribute to the overall cumulative evidence base for digital preservation practice as called for in the 2015 National Digital Stewardship Agenda. The results of the survey identify trends in the national capacity and provide a snapshot of how much content stewardship organizations are actively preserving. The survey also raises significant questions about current storage practices for memory institutions and identifies the saturation of preservation standards and the evolution of best practices as they are adopted.

The first NDSA storage survey was conducted between August 2011 and November 2011. Responses were received from 58 of the 74 members, who stated that they were actively involved in preserving digital content at the time. This represents a 78% response rate. NDSA had a total of 98 members during that period.

The second survey was conducted between April 2013 and July 2013. Responses were received from 78 of the 124 members, who stated that they were actively involved in preserving digital content at the time. This represents a 61% response rate. Targeted followup with a random sample of 5 nonresponders increased the final number of responders to 81 for a final response rate of 65%. There were a total of 167 members of NDSA during that period.

Note that these percentages varied by organizational role. Not all respondents answered all questions, although question-level non-response was generally quite low. Throughout this article, proportions reported are calculated as a percentage of those responding to the specified question. To support further analysis of response rates, replication, and reanalysis, we have deposited a deidentified open access version of the response data in a public archive.2 Prior to conducting the second survey, the NDSA Infrastructure group reviewed feedback from the 2011 survey respondents. The group revised the survey questions to better identify key issues around the long-term preservation of digital content and to clarify topics. The group strove to maintain continuity between the initial survey conducted in 20113 and the second survey launched in 2013 in order in order to evaluate the changes to storage practices within the NDSA community over time.

The respondents from both surveys represent a diverse cross section of organizations working with preservation storage systems including university libraries, consortia, institutes, state and federal government agencies, special libraries, museums, content producers, and commercial businesses.

A Glossary of Terms related to storage practices used in this article can be found in Appendix I.

2 Longitudinal Trends Within Memory Institutions

Organizations that responded to the survey in both 2011 and 2013 provided unique longitudinal insights into their storage practices. These responses show that the memory institutions have a significant continuity of responsibility, priorities, and of workflow. In reviewing the responses from the memory organizations that completed both the 2011 and 2013 surveys, we find that organizations are relatively stable over time. The longitudinal responses show:

- Organizations have a consistent perception of mission and responsibility. The vast majority, 89% of longitudinal respondents, report they remain responsible for their content for an indefinite period of time. These organizations are making their storage choices with the understanding that they will need to preserve the digital content they hold through many migration cycles.

- Replication is still considered a key component of digital preservation and a way to significantly mitigate of the risk of loss. Respondents to the 2013 survey show that 72% of organizations keep the same number or more copies of digital content than they reported keeping in 2011.

- Local control of digital content remained important to a significant number of respondents in the 2013 survey; 51% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it was important. Perceptions of the risk of utilizing cloud storage or third-party storage providers did not significantly change among the longitudinal respondents.

- While local control remained important, the longitudinal respondents showed a substantial increase of 14% in willingness to consider or currently participate in a distributed storage cooperative or system (ex. LOCKSS alliance, MetaArchive, Data-PASS), up to 83% from a previous 69%. Respondents do not see these distributed storage cooperatives or systems as being at odds with local control. Rather, these solutions are looked upon as ways to increase the number of preservation copies and create greater geographic diversity, which mitigates risk of catastrophic loss.

3 Lack of Trusted Digital Repository Standards Adoption: Best Practice Is Not Sector Practice

Formalized into an international standard in 2012, ISO 16363, the Trusted Digital Repository (TDR) Standard, was created as a tool to set the requirements for systems that are focused on ensuring long term access to digital content. The survey data provides insight into the extent to which this standard is being adopted by its intended community.

The adoption of the TDR standard continues to be limited. According to the 2013 survey results, only 21 organizations (18%) are making plans to meet the requirements for ISO 16363:2012; while 27 of the organizations (23%) plan to meet the similar requirements of TRAC/TDR checklist. There is also considerable overlap between the organizations planning to meet the ISO and TRAC requirements. These findings are particularly important in that in the 2011 survey 57% of the responding organizations, a total of 32, were making plans to meet trusted digital repository requirements. Even within the longitudinal sample of 35 organizations, 17 of those organizations lowered their level of confidence that they would meet the standard. That is, 37% of the organizations who originally took the survey have backed off of their earlier thoughts that they would attempt to meet these kinds of standards.

Table 1: Trusted Repository Certification from 2013 survey

| Trusted Repository Authority |

Percent of Organizations Certifying

or planning Certification |

| ISO 16363 |

18% |

| TRAC/TDT Checklist |

23% |

| Data Seal of Approval |

7% |

| Other Certification |

4% |

These responses are evidence that the TRAC/TDR standards are not currently being taken up by the preservation and memory community. If any sector might be expected to adopt these standards, it would be organizations committed to preservation. While the survey does not offer direct evidence into why organizations are not pursuing these requirements, discussion of the standards offers insight. The NDSA Levels of Digital Preservation were developed by NDSA working groups in response to organizations expressing a need for a more modular standard than TRAC/TDR. The TRAC/TDR standards are an extensive list of requirements that mix together high-level policy and planning requirements with rather low level technical details. As a result, it is expensive and time consuming to even begin the process of interpreting and prioritizing the activities an organization should pursue.

While we are not seeing the TDR and TRAC repository standards being taken up by library and archive members, they are slightly more popular among the smaller subset of museum members. This is in clear contrast to the members who act as service providers. All of the service providers are either currently meeting or have plans within the next three years to meet the requirements for these standards. This makes sense as the standards serve to provide a level of trust and accountability for the loss of local control that a cultural heritage organization makes by shifting digital preservation activities to a third-party service provider. Service providers are likely meeting or planning to meet these standards because their customers are asking for them. If there is community interest in pushing for wider adoption of the standards, users or memory institution leadership will likely have to make standard adoption a requirement.

4 Industry Practice In Memory Institutions

The NDSA 2013 storage survey included responses from both memory institutions that had participated in the 2011 survey as well as ones new to the NDSA community. Taken as a whole the responses to the 2013 survey showed some shifts and changes in priorities of memory institutions in regards to preservation storage. Given the degree of consistency of response from the longitudinal organizations, this shift reflects more a changing demographic of the respondents rather than a change in viewpoint or practice from the original responders. A large number of organizations joined the NDSA between the 2011 survey and the 2013 survey. The initial 2011 survey featured responses from a number of similarly structured organizations while the 2013 survey reflects the broader memory community.

There were significant shifts between the 2011 and 2013 surveys in the number of respondents using or considering cloud storage services. Organizations showed significantly greater comfort in securing their content on systems outside their control. Specifically, the increase in use or consideration of cloud storage services by the longitudinal respondents shifted from 51% to 89%. Slightly over half of respondents, 51%, reported that local control remains important. This is a significant shift, in 2011 74% of respondents reported that local control was important.

4.1 Content and Capacity in the Network

There was a significant increase in the total digital content stored by memory institutions from 2011 to 2013, even accounting for the growth in NDSA membership. The total digital content stored in 2011 was 27.6 PB while the total size of stored content in 2013 was 66.8 PB. This size reflects all digital content stored by all respondents including multiple preservation copies, access copies, any derivatives, metadata, etc.

The average storage amount reported in the 2011 survey was 492 TB per institution (across 58 organizations). Anticipated need in three years time more than doubled this number. In 2011, institutions' average anticipated need was 1107 TB. In 2013, actual storage use reported by memory institutions averaged 823 TB per institution (across 81 organizations). The anticipated need for storage that the organizations reported for 2016 was approximately 1420 TB per institution. Actual growth rates are even higher than predicted in 2011. On average, institutions have almost doubled their anticipated growth in the span of 2 years. However, outlier institutions heavily skew the averages. These averages do not reflect individual organizational practice because the majority of institutions are at or below 1PB with extreme outliers. For the most part, members described their 2011 collections as between 50-400 TB of digital materials, although one respondent is storing 5 PB.

The averages belie individual organization's storage experience — as illustrated in Table 2, which shows the number of organizations with different levels of storage. The responding memory institutions reflect a highly diverse group storing widely different scales of content. More than 25% of responding organizations fall in the highest quartile with the largest storage use. Likewise, more than 25% of respondents fall in the lowest quartile with very little storage. These extremes mean the "average" storage size and storage growth rates do not closely reflect the typical organization's experience. The median storage size is 25TB — far different than the 1014 TB mean storage. What is typical is that small, medium, and large memory institutions are all seeing significant growth in the 2 year time period.

Table 2: Organization's Responses for Storage Use and Expectations for all Copies in 2011 and 2013

| Storage Space Amount |

2011 Current Storage |

2011 Anticipated Need in 3 Years |

2013 Current Storage |

2013 Anticipated Need in 3 Years |

| Under 10 TB |

18 |

13 |

30 |

17 |

| 10-99 TB |

19 |

13 |

24 |

28 |

| 100-999 TB |

14 |

16 |

18 |

23 |

| 1000+ TB (1+ PB) |

5 |

9 |

9 |

13 |

4.2 Accuracy of Storage Needs Predictions

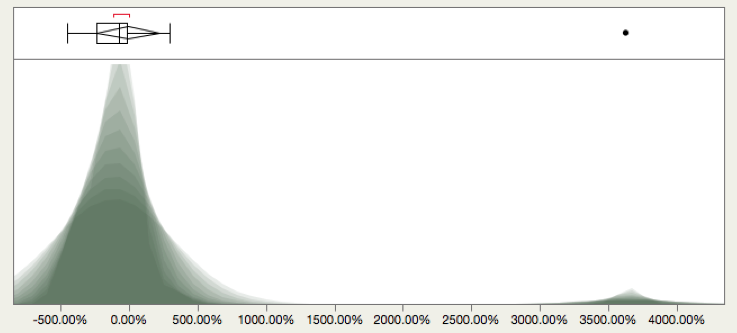

In 2011, institutions were asked to predict their future storage needs over the following three years. The objective of this question was to compare the predicted increases with the actual storage increases in the subsequent survey. The comparison of the prediction with the actual storage growth enables us to evaluate how accurate these predictions were. Figure 1 compares the predicted yearly growth with the actual rate of growth during that time. Typical predictions were off by a substantial percentage. The majority of estimates are well below the actual growth in content.

Figure 1: Content Collection Growth and Predictions

Many organizations vastly under or overestimated estimated the growth of their storage needs over time. As mentioned above, on average, organizations nearly reached their predicted three-year storage growth in the space of only two years. Worldwide data production continues to increase dramatically. In 2013, Science Daily reported "90% of all the data in the world has been generated over the last two years." Approximately 660 billion digital photos were taken in 2013. In the face of this expanding universe of content, memory institutions are attempting to gauge future storage needs based on past acquisition performance. While production assumptions do not directly correlate to preservation assumptions, organizations nevertheless find themselves identifying, collecting, stewarding, and providing long-term access to more content as content creation continues to increase. We expect that organizations will continue to refine their prediction mechanisms over the coming years and develop more accurate growth predictions.

4.3 Desires for Storage Practice

In addition to capturing current storage usage, adoption rates of standards, and organizational policies, the NDSA storage survey also identifies storage priorities within the memory institution community. The ranking of these priorities is shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3: 2011 Survey results on Functionality and Priorities

| Functionality |

Priority Scores (1 low, 7 high) |

Sum of priority scores |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| More built-in functions (like fixity checking) |

0 |

3 |

0 |

9 |

14 |

16 |

13 |

299 |

| More automated inventory, retrieval, and management services |

0 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

17 |

10 |

15 |

295 |

| More storage |

0 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

12 |

12 |

17 |

291 |

| Higher performance processing capacity (ex. Indexing on content) |

0 |

3 |

5 |

6 |

21 |

13 |

6 |

270 |

| File format migration |

2 |

3 |

4 |

10 |

17 |

9 |

9 |

261 |

| More security for the content |

1 |

5 |

6 |

15 |

13 |

8 |

8 |

258 |

| Block level access to storage |

11 |

16 |

5 |

11 |

7 |

4 |

0 |

161 |

Table 4: 2013 Survey results on Functionality and Priorities

| Functionality |

Priority Scores (1 low, 7 high) |

Sum of priority scores |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

| More storage |

8 |

5 |

2 |

8 |

11 |

8 |

40 |

439 |

| More automated inventory, retrieval, and management services |

1 |

6 |

12 |

14 |

18 |

21 |

10 |

391 |

| More built-in functions (like fixity checking) |

4 |

7 |

11 |

11 |

15 |

23 |

11 |

385 |

| More security for the content |

3 |

14 |

17 |

19 |

14 |

7 |

8 |

326 |

| Higher performance processing capacity |

5 |

17 |

15 |

15 |

14 |

11 |

5 |

315 |

| File format migration |

12 |

12 |

20 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

7 |

299 |

| Block level access to storage |

49 |

21 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

141 |

Functionality priorities remain fairly consistent over both surveys. The 2013 survey revealed that more storage became the top priority for the memory institution community, a move up from the third priority in the 2011 survey. This shift in priority correlates with the growth of storage needs discussed above. Significantly, inventory and management services, and built-in preservation functions such as fixity checking remained a high priority. The top three priorities were reshuffled in the 2013 survey but all three remained in the top three. The high-need areas of storage, built-in functions, and more automated inventory, retrieval, and management services that have been consistently prioritized by respondents in both the 2011 and 2013 survey are opportunities for work that could have a high impact.

The remaining functionalities stayed in the bottom four but changed order: security for content moved up the priority list while high performance processing capacity moved down. Built-in preservation functions such as fixity checking remained a top priority. As in the 2011 survey, block-level access is the lowest priority in the 2013 survey; 84% of respondents list it in the bottom two priorities. It is simply not a priority for the respondents of these surveys.

4.4 Availability Requirements and Storage Media Choices

Responses to the 2013 NDSA storage survey reveal a shift in the requirements for access from memory institutions, as summarized in Table 5. In 2011, 40% of respondents required only eventual access for some of their digital collections, the longest response time for access available. That number dropped to 31% in the 2013 survey as availability requirements for content increased. Nearline access, storage able to be made available to the user in the same session without human intervention, also decreased. Only 11% of organizations required nearline access of their content; this is a 17% drop from the 28% of respondents that required nearline access for some of their collections in 2011. Memory organizations requiring offline access within two days held relatively steady — 21% of respondents required this level of availability of access, down 3% from the 2011 survey.

Table 5: Requirements for Availability of Access 2013*

| Access Type |

2013 Requirements |

2011 Requirements |

| Online Access |

30% |

59% |

| Nearline Access |

11% |

28% |

| Online Access Within 2 Days |

21% |

24% |

| Eventual Offline Access |

31% |

40% |

4.5 Mitigating the Risks of Regional Disaster Threats

Maintaining multiple copies of data is critical for ensuring bit level integrity of digital objects. The memory organizations surveyed in the 2013 survey kept up to seven copies of content for organizations. Over 83% of memory organizations are keeping at least one preservation copy, and only 13% are keeping 4 or more copies. Beyond geographic distribution, there is also a need to protect digital content from the kinds of events that could damage many or all of those copies at once. For this reason, best preservation practice requires that an organization maintain at least one copy of materials in an area with different geographical disaster threats. The NDSA storage survey data from the 2013 survey offers insight into the extent to which respondents are meeting this requirement and exactly how they are doing so.

When asked "Is your organization keeping copies of digital assets in geographically distinct places to protect from regional geographic disasters?" memory institutions responded:

- 62% of organizations geographically distribute material for their complete holdings

- 30% of organizations do not geographically distribute their digital content at all

- 8% of organizations geographically distribute a selected subset of their digital holdings

Thus, 70% of the member organizations are meeting this preservation best practice, for at least their highest priority content. Actual practice and best preservation practice are closely aligned in this area.

Organizations are ensuring geographical redundancy in a variety of ways. In the 2013 survey, the majority, 42% of organizations, manage their own copies in one or more geographically distinct offsite locations, 9% meet this requirement through a collaborative partnership like MetaArchive, and 23% meet the requirement by keeping one or more copies with another institution or a third party commercial provider.

4.6 Cloud Storage, Collaborative Storage, and Third Party Storage

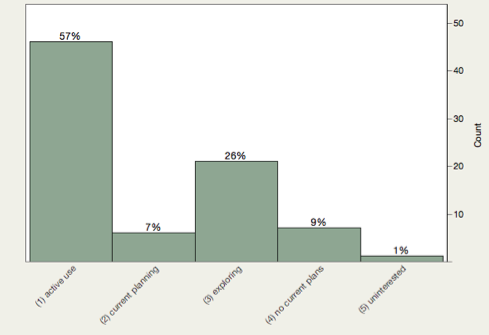

In the 2013 survey, as illustrated by Figure 2, 57% of organizations were using some type of non-local storage, up from the 43% using non-local storage in the 2011 survey.

Figure 2: Non-Local storage.

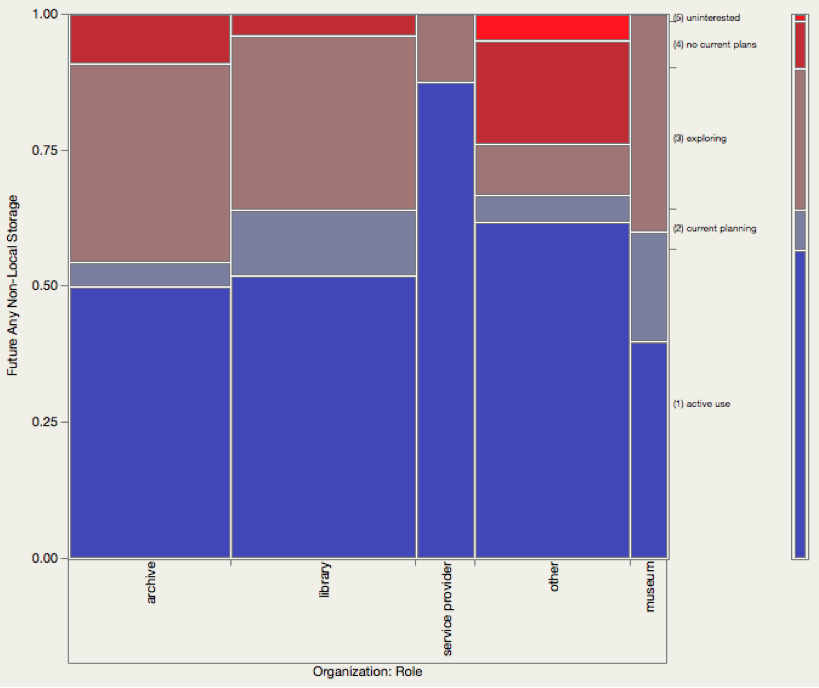

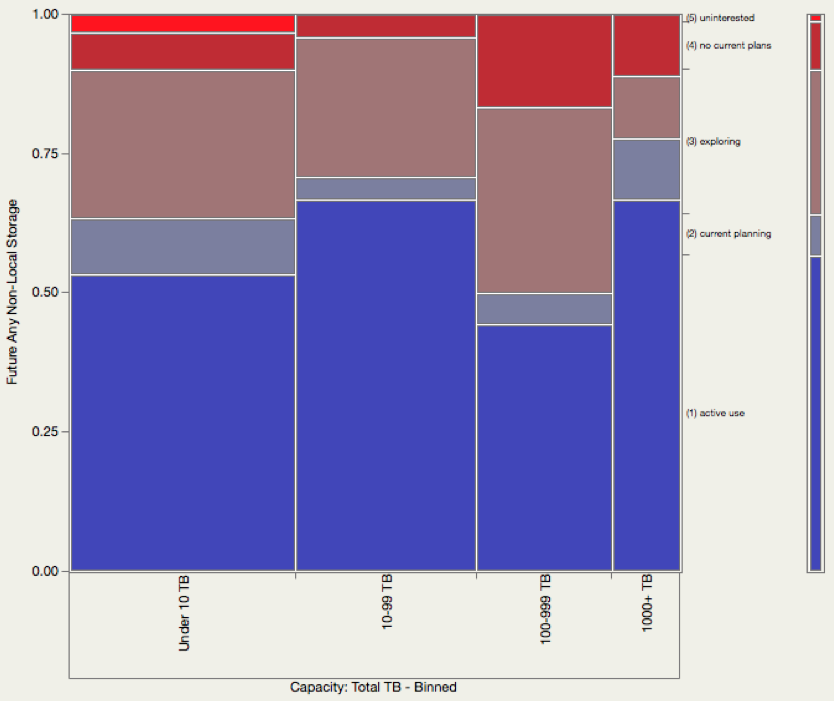

There is some variation in the use of non-local storage across types and capacities of organization, as illustrated in Figures 3a and 3b. There is also differentiation among the non-local services. Cloud storage was in active use by 25% of respondents and 47% of respondents were planning to use cloud services or exploring the use of cloud services for the future. Collaborative storage was actively used by 35% of respondents and 29% of respondents were planning to use or were exploring the use of collaborative storage in the future. Third party storage solutions were the least widely employed remote storage choice. Only 10% of respondents were actively using storage solutions provided to them by vendors or others. An additional 13% were planning to use or exploring the use of other third party storage in the future.

Figure 3a: Non-Local storage by institution type.

Figure 3b: Non-Local storage by capacity.

Third-party storage solutions are choices that are closely connected to a memory institution's comfort with sharing control of its data. Organizations that are more neutral about the idea of local control are more likely to entertain the option of having their content storage hosted by an external party — whether that is in a collaborative or by a service provider. While 51% of respondents to the 2013 survey agree or strongly agree that local control is important, 33% feel neutral, and only 16% disagree, or strongly disagree. Local control is important to the majority of memory institutions due to their concerns about the cost of long-term storage, legal access, being able to verify content, and general access and control of digital content.

The 49% for whom local control is not a strong priority is a significant increase from the 26% of respondents who shared that view in 2011. Concerns about local control seem to be less about memory institutions having the ability to manipulate the digital content in their holdings — see the discussion above regarding 84% of organizations identifying block-level control in the bottom two of their storage feature priorities — and more about trusting their own organization to host, maintain, and control the infrastructure in which the digital content is stored while doubting the ability and integrity of a third party. However, we are seeing practices emerge in the community that significantly change the comfort level for certain non-local control practices. This is in part why third party storage service providers have been among a small subset of organizations to do TRAC auditing and use the TDR checklist. These public displays of trustworthiness may be significantly contributing to an organization's willingness to store their digital content offsite.

Another factor to consider is that the 2013 survey does not show a wholesale shift from purely local control to only hosted storage. Rather, comfort with non-locally held data seems to be driven in part by organizations using collaborative and service hosted storage in addition to their local holdings. It is unclear from these surveys if there are certain practices that are more likely to be employed under locally controlled environments vs. ones that organizations are comfortable having take place in a collaborative or hosted environment. That is to say, what do memory organizations need local control for? What are the digital stewardship lifecycle steps that need to be done in-house and which, with the appropriate assurances and transparency in place, can they become comfortable with happening in a distributed environment?

4.7 Fixity and Auditing of Collection Information

Fixity information offers evidence that one set of bits is identical to another. The PREMIS data dictionary defines fixity information as "information used to verify whether an object has been altered in an undocumented or unauthorized way."4 The most widely used tools for creating fixity information are checksums (like CRCs) and cryptographic hashes (like MD5 and various SHA algorithms)." The requirements to collect, track and manage fixity information are foundational to digital preservation activities.

Fixity checking can, to an extent, stand in for active engagement with digital preservation. Therefore, it is useful to note the extent to which organizations are meeting the most basic and more advanced requirements for fixity checking. There was significant change in memory organizations performing fixity over the two surveys. We can see that 36% of NDSA member organizations in the 2013 survey were not currently doing fixity checks on their content. This is a significant increase in organizations not performing fixity checks from the 20% in the 2011 survey. The increase in lack of fixity checking reflects the growth in NDSA membership and respondents to the survey as discussed earlier.

There is significant room for improvement in employing fixity checks in the digital stewardship community. The 2013 survey results underscore the need for solutions to this issue. Given that the respondents of the survey are memory institutions committed to issues of digital preservation, it is likely that these organizations are performing more fixity checking than organizations outside the NDSA community. It is fair to say that fixity checking is an area in which many institutions can improve.

Beyond simply checking fixity at some point, the survey data also provides insight into the quality of checking organizations are doing. Level three of the file fixity and data integrity category of the NDSA Levels of Digital Preservation is a good example of high-quality fixity checking. It requires that content be checked at fixed intervals.5 There was a decline in organizations performing fixed interval fixity checking. Only 28% of the organizations in 2013, down from 34% in 2011, are comprehensively checking the fixity of their digital objects at fixed intervals. In other words, almost 72% of respondents are not engaged in checking all of their content at fixed intervals. The 2013 survey revealed that 21% of the organizations (down from 32% in the 2011 survey) are sampling their collections to perform random checks on their digital content, which has a somewhat similar effect to auditing content but is less intensive on computing resources. The result of not meeting this requirement is that four out of five responding memory organizations could not offer assurance that:

- All of their digital assets are accounted for.

- Their critical digital assets are intact and safe from silent corruption.

The good news is that transactional fixity checking is the most popular method for checking fixity. By transactional fixity, we mean the checking the fixity of copies of digital objects during and around transactions or movements of the data such as acquisition, access, migration, or other preservation lifecycle transactions. Given that transactions represent one of the biggest potential threats to a digital object, and that the act of finding and retrieving the object are the most intensive part of doing a fixity check, it makes sense that many organizations do this kind of transactional checking. Transactional fixity checking is a significant step in protecting digital files, however, it does not identify bitrot, or the potential degradation of data at rest. An even smaller subset of 16 organizations (17% of the 2013 respondents down from 18% in the 2011 survey) are using tamper-resistant methods (like LOCKSS or ACE) for fixity checking and 17 organizations (20% up from 17% in the previous survey) are storing fixity information in an independent system.

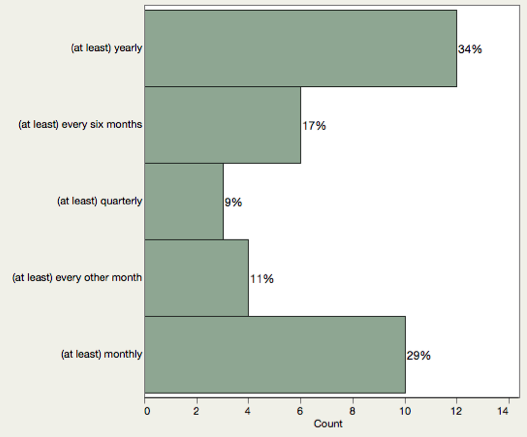

Of the 25 organizations checking fixity of all materials at fixed intervals there is a significant range of fixed intervals that different organizations are using, as displayed in Figure 4 ranging from 29% that were checking on a monthly basis, to 34% that check annually. In many cases, organizations checking at fixed annual intervals are also checking on transactions, so high use items are being checked more frequently than that but all the items are checked on at least an annual basis.

Figure 4: 2013 Periodic Interval Fixity Checking

While the relatively low numbers in some of the more advanced components of maintaining fixity information are noteworthy, the fact that 36% of responding organizations are currently not doing any fixity checks is even more critical. There is considerable room for improvement in the tactics organizations are using to ensure, and be able to attest to, the fixity of their content. This improvement is attainable as there are a number of tools that can support this work. It is critical that organizations stewarding information for the long haul work toward performing at least basic levels of fixity checking.

5 Summary

General preservation practices are not always reflective of community best practice standards — particularly regarding TRAC/TDR. Organizations providing storage and other preservation services to the preservation community have led the way in adopting the standard. It is worth noting that in the absence of a demanding clientele or stakeholder community, the standard does not seem to be widely adopted.

Memory institutions are increasingly preserving more digital content and requiring more storage capacity to do so. There is significant continued growth in the need for preservation storage space. The content holdings of memory institutions can be expected to continue to grow over in the coming years. These two surveys revealed that the rate of growth of their digital content within an organization is outstripping their expected projections. Organizations currently underestimating the rate of growth of their digital content will likely refine their calculations for growth over time. Expectations for digital content growth will more accurately reflect real growth as these calculations are refined.

Organizations are requiring quicker access to their stored content in 2013 than in 2011. This trend toward ready access will likely continue. While constant online availability of content drives up storage prices, the demand for it is increasing. It is likely we will see continued increase in demand for nearline availability and rapid offline access (2 days or less), with the need for eventual access continuing to shrink. This seems to be part of an overall trend emphasizing access and availability.

On average, organizations have a strong record of mitigating against potential disaster threats. Everyday threats such as bit rot that need to be mitigated through routine mechanisms such as regular interval checksumming are not as well managed. Regular fixity checking is an opportunity for improvement for memory organizations, particularly given the increase in available tools.

Notes

| 1 |

Authors Altman and Gallinger take primary responsibility for the correspondence and the content and conclusions. We describe contributions to the paper using a standard taxonomy (see Allen L, Scott J, Brand A, Hlava M, Altman M. Publishing: Credit where credit is due. Nature. 2014;508(7496):312-3.). Altman, Bailey, Cariani, Gallinger, Owens were responsible for the initial conceptualization of the research. All authors contributed to survey design. Micah Altman was responsible for reviewing and refining the survey instrument; designing and performing the statistical analysis and computations. The NDSA Infrastructure Working Group contributed to the survey instrument, to survey implementation and to review on the manuscript itself. |

| 2 |

Replication data and a copy of the survey instrument is archived in the Harvard Dataverse network:

Altman, Micah, 2017. "Replication Data for: NDSA Storage Report 2017", Harvard Dataverse, V1. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8NYC97 |

| 3 |

See Altman, et al., 2013. NDSA Storage Report: Reflections on National Digital Stewardship Alliance Member Approaches to Preservation Storage Technologies, D-Lib Magazine, 19(5/6). https://doi.org/10.1045/may2013-altman |

| 4 |

PREMIS Data Dictionary for Preservation Metadata version 3.0. Last modified November 2015. |

| 5 |

NDSA Levels of Preservation. Last modified April 2013. |

Appendix I: Glossary of Terms Used in This Document

Access Storage: Storage designed to contain and serve content to users through common protocols such as the web. Often, this is assumed to be available on a public website (or one accessible to a large group of users such as all students and faculty of a university).

Block-level Access: Reading and writing to disks at the physical level. Only system engineers use block-level access to specify or identify exactly where data are stored, generally for performance reasons.

Dark Archive: Storage designed to be inaccessible (except for authorized storage system managers).

Fixity: The property of a digital object being constant, steady, and stable.

Fixity checking: The process of verifying that a digital object has not been altered or corrupted.

High-performance availability: It includes access to large numbers of simultaneous users or for high performance computing.

Nearline Storage: Storage generally designed to provide retrieval performance between online and offline storage. Typically, nearline storage is designed in a way that file retrieval is not instantaneous but is available to the user in the same session.

Offline Storage: Storage recorded on detachable media, not under the control of a processing unit (such as a computer).

Online Storage: Storage attached under the control of a processing unit (such as a computer) designed to make data accessible close to instantaneously.

Preservation Storage: Storage designed to contain and manage digital content for long-term use.

About the Authors

Michelle Gallinger is Principal Consultant at Gallinger Consulting where she provides technological insight into decision-making processes for libraries, museums, archives, and businesses. She gives strategic planning guidance; develops policies, guidelines, and action plans for her clients; offers stakeholder facilitation services; and coordinates collaborative technological initiatives. Gallinger's clients include Harvard Library, Institute of Museums and Library Services, Metropolitan New York Library Council, Ithaka S+R, and the Council of State Archivists (CoSA). Prior to consulting, Gallinger worked at the Library of Congress developing the initial strategy for and led the creation, definition, and launch of the National Digital Stewardship Alliance in 2010. Gallinger performed policy development, strategic planning, program planning, and research and analysis at the Library of Congress.

Jefferson Bailey is Director of Web Archiving at Internet Archive. Jefferson joined Internet Archive in Summer 2014 and manages Internet Archive's web archiving services including Archive-It, used by over 500 institutions to preserve the web. He also oversees contract and domain-scale web archiving services for national libraries and archives around the world. He works closely with partner institutions on collaborative technology development, digital preservation, data research services, educational partnerships, and other programs. He is PI on multiple grants focused on systems interoperability, data-driven research use of web archives, and community news preservation. Prior to Internet Archive, he worked on strategic initiatives, digital collections, and digital preservation at institutions such as Metropolitan New York Library Council, Library of Congress, Brooklyn Public Library, and Frick Art Reference Library and has worked in the archives at NARA, NASA, and Atlantic Records. He is currently Vice Chair of the International Internet Preservation Consortium.

Karen Cariani is Senior Director at WGBH Educational Foundation where she oversees the WGBH Media Library and Archive. She pursues opportunities for the WGBH archive to be actively used in educational endeavors through new technology and is particularly passionate about science education and the use of media to teach science and math. Karen has worked at WGBH since 1984 in television production and archival-related roles. She has 20 plus years of production and project management experience, having worked on numerous award-winning historical documentaries including MacArthur, Rock and Roll, The Kennedys, Nixon, and War and Peace in the Nuclear Age. She also worked with the WNET, PBS, NYU and WGBH Preserving Public Television partnership as part of the Library of Congress National Digital Information Infrastructure Preservation Project. She served two terms (2001-2005) on the Board of Directors of the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA). She was co-chair of the AMIA Local Television Task Force, and Project Director of the guidebook "Local Television: A Guide To Saving Our Heritage," funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. She was co-chair of the LOC National Digital Stewardship Alliance Infrastructure Working Group. She is active in the open source Samvera project community and serves on the NEDCC advisor council. Currently, Karen is also WGBH's Project Director of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, a collaboration with the Library of Congress to preserve and make accessible public TV and radio content. She seeks to improve access to digital media collections and broaden their use and relevance.

Trevor Owens is the Acting Associate Deputy Director for Libraries at the Institute of Museum and Library Services. He previously worked on national digital preservation strategy in the Office of Strategic Initiatives at the Library of Congress, and open source software projects at the Center for History and New Media.

Micah Altman is Director of Research and Head/Scientist, Program on Information Science for the MIT Libraries, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Previously Dr. Altman served as a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at The Brookings Institution, and at Harvard University as the Associate Director of the Harvard-MIT Data Center, Archival Director of the Henry A. Murray Archive, and Senior Research Scientist in the Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences. Dr Altman conducts work primarily in the fields of social science, information privacy, information science and research methods, and statistical computation — focusing on the intersections of information, technology, privacy, and politics; and on the dissemination, preservation, reliability and governance of scientific knowledge.