|

D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2015

Volume 21, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

Facing the Challenge of Web Archives Preservation Collaboratively: The Role and Work of the IIPC Preservation Working Group

Andrea Goethals, Harvard Library

andrea_goethals@harvard.edu

Clément Oury, International ISSN Centre

clement.oury@issn.org

David Pearson, National Library of Australia

dapearso@nla.gov.au

Barbara Sierman, KB National Library of the Netherlands

barbara.sierman@kb.nl

Tobias Steinke, Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

t.steinke@dnb.de

DOI: 10.1045/may2015-goethals

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

Accessing the web has become part of our everyday lives. Web archiving is performed by libraries, archives, companies and other organizations around the world. Many of these web archives are represented in the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC) . This article documents goals and activities of the IIPC Preservation Working Group (PWG), such as a survey about the current state of preservation in member web archives and a number of collaborative projects which the Preservation Working Group is developing. These resources are designed to help address the preservation and long-term access to the web by sharing ideas and experiences, and by building up databases of information for support of preservation strategies and actions.

1 Introduction

Many cultural heritage organizations, government agencies and companies have a responsibility, often mandated, to collect and preserve digital publications. As documents are increasingly published directly via the web this responsibility has expanded to include web archiving. The task of web archiving is a new challenge for the preservation of cultural heritage. The increasing role of the web in political, social or cultural lives of contemporary societies is now obvious; and future historians will require access to older parts, older "layers" of the Internet. [1] However, web content changes or disappears very fast, even on the most trusted or popular websites [2]. All these organizations face many challenges because the technical process of harvesting and managing access to archived content is difficult. New web technologies and content types demand constant adjusting and changing of tools and workflows.

Digital preservation of publications like e-books, e-theses and e-journals is also still a challenge for digital libraries and archives. There are strategies such as migration and emulation (or a combination of both recurring over time) to enable access to objects for no longer supported system environments, but the practical problems of recognizing and dealing with various file formats on a large scale are still difficult tasks. Digital libraries and archives address these challenges with trained staff, preservation policies and dedicated archival systems that conform to the OAIS reference model.

Web archives are often separate units in many digital preservation infrastructures because of the specific challenges. Although preservation planning and actions may be in place for other digital collections, web archives are often not included in these procedures. This is largely because there are still many open questions about the specific preservation challenges for web archives. For example, are there already obsolete technologies in web archives that prevent or limit access to the content? What is the meaning of authenticity and faithful rendering for web pages? Attempts to reflect some of the complexities of web content have been expressed in various dedicated preservation policies. These include such statements as:

"Content, connections and context are of primary importance. How it is ultimately presented to a user is a secondary consideration."

or

"We accept ... that what is to be preserved is not a mirror representation of the web nor of a website but, rather, a snapshot of content that was once arranged and published as a website, with only limited functionality of the original. The archived artefact is formed out of the collecting process which is inevitably lossy. Our aim is to define and control this loss. In addition, the way in which the content is collected and displayed places a significant limitation on the presentation of the archived artefact as an authentic record of the publisher's original data or of the version of that data originally published on the web." [3]

As digital objects in general are getting more complex, the findings of preservation solutions for web archiving should also be applicable in other digital preservation areas. This goal is best achieved by co-operation and by building communities. The web is international and therefore it makes sense to work together on an international level.

2 International Cooperation: The Preservation Working Group

2.1 Goals of International Cooperation

Since the early days of web archiving, international cooperation was thought to be critical to ensure that websites and online publications will still be available to future generations. The International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC) is a prominent example of collaborative work. When it was founded in 2003, it grouped together the pioneer web archiving institutions, among them the Internet Archive, and seven national libraries. In 2015 there are 49 members, but its goals remain unchanged:

- Enable the collection of a rich body of Internet content from around the world to be preserved in a way that it can be archived, secured and accessed over time.

- Foster the development and use of common tools, techniques and standards that enable the creation of international archives.

- Encourage and support national libraries everywhere to address Internet archiving and preservation.

2.2 The Role of the PWG

The scope of the IIPC covers all parts of the web archiving workflow. The best known tools hosted and maintained by the IIPC are dedicated to web crawls (Heritrix) and access (the Wayback Machine). But there are also outputs related to long-term preservation. The Preservation Working Group was established within the IIPC in 2007. Its first mandate was to characterize web archives, i.e. to identify their specific preservation needs. More specifically, the PWG was mandated to identify relevant approaches, standards and practices already used for preservation of other digital assets; to report on how they might be used with archived web resources and/or to identify the gaps and promote new approaches. The survey described in Section 3 is a continuation of this gap analysis work.

2.3 Fostering Policies for Web Archives

A minority of institutions have defined specific preservation policies for web archives, although they seldom make them publicly available. In order to identify what kind of specific policies are needed — if any — the PWG acts as a forum where ideas and examples are exchanged and discussed. It also seeks to raise awareness beyond the group of web archiving institutions, by publishing papers or participating in conferences, such as [4], [5] and [6]. PWG members participated in the publication of an ISO Technical Report (see ISO/TR 14873:2013) intended to standardize "statistic and quality issues for web archiving" [7]. Terminologies, a standardized way of calculating statistics, and key indicators are notably provided in the field of web archive preservation, to help institutions to build their own policies.

2.4 Supporting Tools Development

Software tools are critical components of web archive preservation activities, especially file format identification and metadata extraction tools. However, institutions often use such tools only on non-web material, probably due to the scalability issues of web archives. Web archiving institutions generally use container formats to store files harvested from the web: the ARC format or its successor, the WARC format. For this reason PWG members focused on these two specific formats in various working group projects. ARC, designed in 1996 in the pioneer years of web archiving, is a container format where all harvested web files are stored as internal embedded records, along with selective metadata (URL, harvesting date, checksum, etc.). WARC is essentially an improvement of the ARC format, with unique identifiers for each record and a larger set of supported metadata. The main advantage of the WARC format is that it is an official ISO standard (ISO 28500:2009).

The PWG promoted the development of tools, such as JHOVE2 modules for web archives. JHOVE2 is the new version of the widely adopted JHOVE1 validation and characterization tool. Compared to JHOVE1, this new version offers two main features that are especially of interest for web archives. First, it separates identification of file format from the more detailed validation and characterization functions. The latter is performed by specific JHOVE2 modules (a new module has to be developed for each format), whereas the former is performed by other tools (notably DROID). Second, JHOVE2 is able to perform analyses at different levels when it deals with container formats. It is thus able to validate and characterise ARC or WARC container files and then (optionally) identify, validate and characterize all files contained within as ARC or WARC records.

The development of a first set of modules was funded by the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) as part as the development process of the web archives ingest module for its digital repository [8]. The BnF contracted a private company to develop a GZIP and an ARC module for JHOVE2, and opened the possibility to use the File utility instead of DROID in the format identification process. BnF specifications were reviewed by PWG members, notably by the California Digital Library, responsible for the core development of JHOVE2.

The second development project, directly funded by the IIPC and performed by the National Library of Denmark, added a module to JHOVE2 for the WARC format.

PWG members contributed to these two achievements by writing specifications and performing tests. However, the PWG as a whole was not directly managing the projects as this was done directly by IIPC member institutions. In contrast, the PWG is the leading force behind the current development of two databases, one dedicated to risk assessment, the other to web environment documentation, which will be explained in more detail in Section 4.

For the work of the PWG it is important to understand the needs and the current situation in web archives. There are regular meetings and discussions as well as surveys to gather information.

3 A Survey of the State of Preservation in Web Archives

As a part of understanding the state of digital preservation of web archives, in April 2013 the IIPC Preservation Working Group (PWG) distributed a survey amongst the IIPC members. This survey was developed to get a better understanding of the current preservation practices in web archiving. The IIPC members can be seen as the pioneers in web archiving and the PWG was interested in a realistic view of what is happening or is not happening in members' archives. The PWG will use the survey findings to plan new activities and research. The survey was sent to the (at that time) 46 members of the IIPC, while responses were restricted to one per institution. Twenty-seven surveys were received, of which 25 were complete.

The survey focused on the following topics: Policy, Access, Preservation Strategy, Ingest, File Formats and Integrity. Almost all questions could be answered via a simple tick box (for example: "Yes", "Plan to", "No") and only one question allowed free text. A second survey is planned to get more free text answers on specific topics which required further elaboration.

A preservation policy is generally seen as guidance for preservation activities in an organisation and, if made publicly available, also as a way to inform stakeholders and peers about the intentions of the archiving organisation. The first question "Do you have a preservation policy?" was confirmed by a majority of 21 respondents (78%) while 5 (18%) responded that they were planning to, and one (4%) answered "No". The next question tried to find out whether "web archiving" received special attention in a preservation policy by asking "Are there specific points about web archiving in your preservation policy?" Thirty-three percent (9 respondents) answered "Yes", while 26% (7 respondents) are planning to put specific points about web archiving in their preservation policy. The specific elements that need to be added for web archives still need to be investigated. Eleven (41%) did not have any specific web archiving elements in their policy. For the question "Do you have a dedicated digital preservation system?", 70% (19) answered "Yes", while 22% (6) are planning to have one. Two organisations answered "No".

The PWG wanted to explore how web archive content is treated as compared to other preserved digital material, hence the next question "Is your web archiving collection integrated in your preservation system?" Ten organisations (37%) have it integrated, while another 7 (26%) are planning to, and 10 (37%) organisations have not integrated their web collection. This also is an interesting point to investigate especially as this situation might influence other preservation activities.

Giving access to the web archive is the main goal of preservation activities. To optimize this access, an organisation might decide to create a separate environment to give access. But is this happening in reality? On the question "Do you have separate access and preservation copies in your web archive?", 33% (9) answered "Yes", while 4 (15%) respondents were planning to do this. The rest, 52% (14) did not have separate copies. The use of web archives is changing, with a growing demand for large sets of web archives to do data mining studies. "Do you give access to your raw web data for research purposes (data mining)?" received a confirmative answer by 4 (15%) organisations. That this is an emerging field is shown by the 15 organisations (55%) that are planning to give this kind of access, while 8 (30%) answered "No".

A set of questions were asked under the heading "Features of your digital preservation system". Further investigation is needed to determine whether the answers reflect the actual use of these features (like file format identification and extracting metadata) or just the existence of the features in the preservation system. How the question was interpreted might have influenced the answers given to two other questions in relation to strategies. On the question "Do you have a preservation strategy for your web archive?" the organisations answered:

| Bitstream Only | 10 (37%) |

| Migration | 1 (4%) |

| Emulation | 0 (0%) |

| Not Decided Yet | 16 (59%) |

And the question "Is file format obsolescence an urgent problem in your web archive?" led to a majority of answers "not yet" 14 (52%) or "Don't know" 8 (30%) or "No" 2 (7%), while 8 organisations (30%) indicated that they were already confronted with this problem. These answers might be related to the features in the digital preservation system or the tools available. The following table shows the answers received on the detailed questions on features of the institution's digital preservation system. For these questions a distinction was made between non-web material and all material (web material included) being preserved.

| |

Yes, but only

non-web material |

Yes, all digital objects

including web material |

No |

Plan to |

File format identification

for individual files (within ARC/WARC) |

4 (15%) |

8 (31%) |

7 (27%) |

7 (27%) |

Technical metadata

extraction/enhancement on file level |

11 (41%) |

10 (37%) |

2 (7%) |

4 (15%) |

| Virus checking on ingest |

5 (19%) |

7 (26%) |

12 (44%) |

3 (11%) |

| Regular integrity checks |

12 (44%) |

5 (19%) |

3 (11%) |

7 (20%) |

| File format normalization on ingest |

3 (11%) |

2 (7%) |

18 (67%) |

4 (15%) |

| Support for file format migration |

8 (30%) |

3 (11%) |

6 (22%) |

10 (37%) |

| Support for automatic emulation for access |

2 (8%) |

0 (0%) |

16 (64%) |

7 (28%) |

| Content replication |

5 (18%) |

15 (56%) |

4 (15%) |

3 (11%) |

Although the results of this survey introduce additional questions that need to be explored in more depth, in general the results reveal the current web archiving preservation environment of IIPC member organizations.

This survey also shows that long term preservation planning and strategies are still lacking to ensure the long term preservation of web archives. Several reasons may explain this situation: on one hand, web archiving is a relatively recent field for libraries and other heritage institutions, compared for example with digitization; on the other hand, web archives preservation presents specific challenges that are hard to meet.

To help meet the challenges the PWG works co-operatively on tools and databases. Collecting and sharing knowledge allow each web archive to find the best fitting preservation strategy.

4 Collecting and Sharing Information: PWG Databases

The IIPC PWG has developed several databases of information meant to support the ongoing preservation planning and activities of IIPC institutions, and ultimately any institution preserving web content (currently work in progress). A few of these are highlighted in this section.

4.1 Risks Database and Assessment Tool

The PWG created both a database of risks to collecting, preserving and accessing web archives and an associated online tool for institutions to assess the risks based on their particular context and mitigation strategies. The database and assessment tool grew out of an earlier PWG effort in 2006 to document the 12 key threats to web archives and potential solutions. In 2009 the PWG began to transform the initial threat list into a more comprehensive set of 68 risks, described and linked to relevant literature, and created a proof of concept online tool to support the ongoing assessment and mitigation of risks.

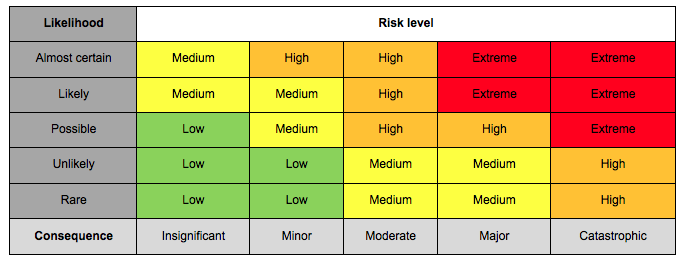

The technique behind the assessment tool is the consequence/probability matrix which combines qualitative measures of probability and consequence to produce risk levels (Figure 1). It was considered well-suited for assessing risks to web archives because there is insufficient information to use quantitative measures, it is simpler than many other risk assessment techniques, and it produces "risk levels" that can be used to prioritize actions within the institution or work within the PWG.

In the proof of concept, a person performing a risk assessment for an institution selects a risk to assess, for example 'archived content becomes corrupted'. The person then estimates the consequence if it were to occur, lists the controls in place to mitigate against the risk, estimates the effectiveness of the controls, and estimates the likelihood of it occurring based on the controls in place. Based on the estimated consequence and likelihood, a risk level is automated calculated using the risk matrix shown in Figure 1, one of: low, medium, high or extreme.

Figure 1: The risk matrix used to automatically calculate a risk level based on likelihood and consequence (conforming to ISO Guide 73:2009).

By performing these assessments, the institution is able to see where they are most at risk. In addition, they can see in the interface how other institutions have assessed the same risks and can compare their answers, for example to see what controls other institutions have in place.

4.2 Environments Database

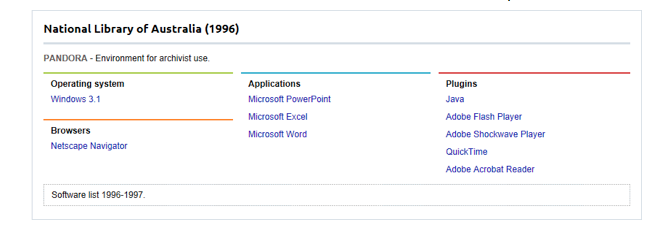

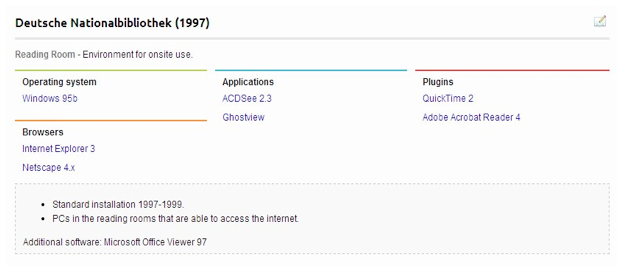

In order to understand what was originally required to access web material (for future preservation actions), the IIPC Environments database documents software stacks, (the operating system, web browsers and plug-ins, and desktop applications), that have been provided to onsite researchers to access, view and render web content in a given year. The IIPC PWG surveyed its members to document what environments its members had used to access web content since 1996 ([9], [10]). The earliest entries come from the National Library of Australia in 1996 (Figure 2) and Deutsche Nationalbibliothek in 1997 (Figure 3). The goal of collating this information is to provide a reference resource of the state of the web at a given period of time which could be used to create a stack through which to provide access to web content of specific periods of time as well as to be used in the future to develop access and preservation strategies for web archives.

Each entry in the database describes an environment, at a given point in time, (currently at various points in time beginning in 1996), and the purpose of that environment. Some of the environments describe those present in reading rooms; others describe those that are for archivist use. Environments are linked to individual software entries with more detailed information of each software component.

Figure 2: An example profile in the environments database documenting the National Library of Australia's environment for archivist use in 1996.

Figure 3: An example profile in the environments database documenting the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek's reading room in 1997.

Since the PWG began documenting environments in the Environments database, two general observations have been made. The environments themselves over time have become significantly more complex, primarily due to the increasing complexity of multimedia. In addition, the ability to accurately and fully describe these environments has become more difficult because the documentation to link to from the database entries is often not available, for example when it is no longer offered on the website of the company that developed the software.

5 Future Plans

The PWG will continue to support projects in the area of digital preservation in web archives as well as improve the available information for preservation planning and actions. The current two databases will be improved and further developed to become a useful tool for the community. Other databases are planned, for example to document the dependencies between web content, services and tools. A documentation of vital dependencies could focus preservation actions and help stabilize web archiving infrastructures.

The Environments database was used as a case study to help define the requirements for the next version of PREMIS which added support for environments [11]. It could also be used for many other things, such as defining requirements for the rendering environments of reading rooms for web archives, or as documentation of preserved environments (e.g. an ISO image, ghost of the desktop preserved in its own sake). Assigning persistent identifiers to all the environment entries would enable citability of the environment descriptions and be a first step towards a linked open data compliant technical registry. The PWG is currently developing a more refined data model for the Environments database which will link related plugins to operating systems (including service packs), general applications and browsers which may in future be linked to downloadable software instances (given survivability and licensing considerations). This more robust data model should allow for a more specific description of specific installations and be more amenable to machine actionable uses. It will also better support the more complex environmental data PWG members have been submitting in recent years. In addition, the PWG wants more of its members to register their environments on a more regular basis, and make it easier to enter their data.

The work of the PWG reflects its member institutions' belief that collaboration and shared documentation are the keys to digital preservation of the web. As an international problem, no single institution can tackle such a large challenge alone, but as a group pooling knowledge, experience and tools, the challenge is made easier.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the IIPC members who contributed to the survey and the databases and also Gina Jones, the co-leader of the Preservation Working Group, and Sébastien Peyrard for reviewing and contributions to this article.

References

[1] Lepore, Jill. "The Cobweb: Can the Internet be archived?". In The New Yorker, January 26, 2015.

[2] Niu, J. 2012. An Overview of Web Archiving. In D-Lib Magazine, Volume 18, Number 3/4. http://doi.org/10.1045/march2012-niu1

[3] Webb, C., Pearson, D. and Koerbin, P. 2013 'Oh, you wanted us to preserve that?!' Statements of preservation intent for the National Library of Australia's digital collection', in D-Lib Magazine 2013 Vol.19, Number 1/2 (Jan/Feb 2013). http://doi.org/10.1045/january2013-webb

[4] Armstrong, P., Coufal, L., Goethals, A., Jones, G, Oury, C. and Pearson, D. 2010. Preserving Web Archives: One Size Fits All? at iPRES 2010, Vienna, (Panel, Session 3, Day 1, 19 September 2010).

[5] Carpenter Negulescu, K., Goethals, A., Jackson, A., Jones, G., Oury, C., Pearson, D., Sierman, B. and Steinke, T. 2012. Preserving Web Archives: Implications and Actions? at iPRES 2012, Toronto, (Panel, Session 3, Day 1, 3 October 2012).

[6] Derrot, S., Grotke, A., Oury, C., Pearson, D., Sierman, B., Signori, B. and Steinke, T. 2013. Getting started in Web Archiving and Web Archives Preservation at iPRES 2013, Lisbon (Tutorial T3.2, 2 September 2013).

[7] Oury, C., and Poll, R. 2013. Counting the uncountable: statistics for web archives. In Performance Measurement and Metrics, Vol. 14 Iss: 2, pp.132 — 141. http://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-05-2013-0014

[8] Oury, C., and Peyrard, S. 2011. "From the World Wide Web to digital library stacks: preserving the French Web archives". In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects (iPRES) (Singapore, November 2011).

[9] Davis, M. 2009. Preserving access — Making more informed guesses about what works — IIPC (Report).

[10] Pearson, D. (prepared by Davis, M.) 2009. 'Preserving access: making more informed "guesses" about what works', at the IIPC Open Day, San Francisco (7 October 2009).

[11] Dappert, A., Peyrard, S., Chou, C. and Delve, J. 2013. Describing and Preserving Digital Objects Environments. In New Review of Information Networking, Vol. 18 Iss. 2, pp. 106-173.

About the Authors

|

Andrea Goethals is responsible for providing leadership in the development and operation of Harvard's digital preservation program and for the management and oversight of the Digital Repository Service (DRS), Harvard's large scale digital preservation repository. She directs the National Digital Stewardship Residency (NDSR) Boston program, participates in the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC) Preservation Working Group, and is the co-chair of the National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) Standards and Practices Working Group.

|

|

Clément Oury is head of the Data, Network and Standards Department at the International ISSN Centre. He was previously head of Digital legal deposit at the National Library of France, and served as Treasurer of the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC). He is also the convenor of two ISO working groups (on the "WARC archiving file format" and on "Statistics and quality issues for web archiving"). He has a PhD in early modern history at the University of Paris-Sorbonne.

|

|

David Pearson has worked in various cultural institutions for the last 20 years and is currently the Manager of the Digital Preservation Section at the National Library of Australia. He has been involved in the IIPC Preservation Working Group since 2008. David has written a number of articles in academic journals on both archaeological and digital preservation issues. David holds a first class honours degree in archaeology from the Australian National University, Canberra and is a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

|

|

Barbara Sierman MA is digital preservation manager at the Research Department of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands. She studied Dutch Literature with a focus on the 18th Century and was library consultant at PICA (now OCLC). After years as an IT consultant at Cap Gemini, she joined the KB in 2005. Barbara is part of the PTAB group, this group created the ISO standards 16363 Audit and Certification of Trustworthy Digital Repositories and ISO 161919 Requirements for bodies providing audit and certification of candidate trustworthy digital repositories. She also introduced the concept of "Preservation Watch" in the PLANETS project and was responsible for the creation of the Catalogue of Preservation Policy Elements in the SCAPE project. She regularly blogs on digitalpreservation.nl/seeds.

|

|

Tobias Steinke is working in the German National Library (DNB) on the conceptual development of digital preservation and is responsible for the web archiving project of the library. He has been involved in national and international projects about digital preservation and in standardization. Tobias is the co-lead of the Preservation Working Group in the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC). He holds a masters degree (Diplom-Informatiker) in computer science from the Darmstadt University of Technology.

|

|