D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2017

Volume 23, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

A Community of Relations: Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes

Kimberly Christen, Alex Merrill and Michael Wynne

Washington State University

{kachristen, merrilla, michael.wynne} [at] wsu.edu

https://doi.org/10.1045/may2017-christen

Abstract

This paper describes the history of Mukurtu CMS and our current project "Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes: A Sustainable National Platform for Community Archiving" funded by the IMLS as part of their National Digital Platform initiative in 2016. This project is an extension of the social, cultural, and technical work of developing the Mukurtu CMS software to the current 2.0.7 release. Mukurtu CMS is community driven software that addresses the ethical curation of, and access to, cultural heritage. The Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes grant will create regional centers of support and training and update the software to a 3.0 release. Each Mukurtu hub will contribute to the software updates and provide local training and support for community users.

Keywords: Mukurtu, Collaborative Curation, Open-source Software, Indigenous, Digital Archives, Access

1 Mukurtu Alpha: Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari Archive

Mukurtu started as a grassroots project to manage, circulate, and narrate the Warumungu Aboriginal community's digital materials using their own cultural protocols. In 2002, after years of collaboration with the Warumungu Aboriginal community in Central Australia, Dr. Kimberly Christen, accompanied a group of community members to the National Archives in Darwin. During this visit, the Warumungu expressed both tension and relief when viewing the images and documents held in the National Archives. The tension centered on the violation of cultural protocols observed by Warumungu people in the distribution, circulation, and reproduction of their cultural materials. For example, images of the deceased were displayed online with no warnings; pictures of sacred sites lacked any connection to the ancestors who care for those places; ritual objects were disconnected from their original context. In addition to this archival material, the Warumungu community received thousands of photos from former missionaries, schoolteachers, and researchers. These digitally returned materials posed a challenge because they could be reproduced endlessly, accessed more easily, and distributed without consent or consultation.

Community members who viewed the photos on Christen's laptop knew what individuals and families should view which items, how they should be shared and who held the knowledge intimately connected to the images of places, kin, and ancestors, and if the materials could be reproduced. The cultural protocols did not need to be spoken; everyone knew what they were and how they should be followed "properly." What the Warumungu community wanted was a platform whose functionality respected their dynamic social and cultural systems, relationships, and cultural protocols for sharing, circulating, and creating knowledge. After evaluating the available commercial content management systems, we discovered a set of unmet needs, including: cultural protocol driven metadata fields, differential user access based on cultural and social relationships, and functionality to include layered narratives at the item level. We were not the only ones to come to this conclusion. Based on feedback from Native communities in the U.S., the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) at the Smithsonian Institution conducted a survey of commercial off-the-shelf content management systems and came to the same conclusion (Hunter, Koopman, & Sledge, 2004).

Between 2002 and 2005, Christen collaborated with Warumungu community members at the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre, the Papulu Apparr-kari Language Centre and Julalikari Arts Center in Tennant Creek, NT, Australia. The three years of work to define and develop the initial "community digital archive" laid the foundation for what would be central to the growth and sustainability of Mukurtu: community collaboration, consultation, and creative production. During community listening sessions, individual and family meetings and work with Warumungu people at each of the Aboriginal organizations we defined the protocols for use, the interface requirements and the overall goals of the platform. In 2005 while viewing one of the demo versions of the archive, Michael Jampin Jones, a Warumungu elder and archivist at Nyinkka Nyunyu, elaborated on the archive's imperative and ultimately its name. Mukurtu — he told Christen — meant "dilly bag" in the Warumungu language. The dilly bags held sacred materials and elders kept and protected them as part of their obligations to care for their communities, relatives, places and ancestors, but the elders could not be "stingy" and had to open them up when younger generations asked respectfully. Therefore, Jampin declared that like the dilly bag — Mukurtu — the digital archive we built should be "a safe keeping place."

In 2007, after two and half years of community consultation, development, and design work we launched the Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari archive as a stand-alone, browser-based, community protocol driven archive, updatable to community needs over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari archive

Explaining the features and functions in this original version highlight the fundamental needs that run through successive iterations. In addition to basic metadata including a unique ID number for each piece of content, dates, names, and places, all material is tagged with a set of "protocols" relating to family relations, gender, and country affiliations. When content is uploaded a specific set of criteria must be considered. Which families can see the image (a pull down menu allows families to be added)? Is the material restricted to men only or women only? Is the image restricted only to those related to specific countries (a pull down menu allows countries to be checked)? Is the image sacred and thus restricted to elders only? Is anyone in the photo or video deceased? Finally, is this material "open" to everyone?

In order to filter search queries, all of the material held in the database was linked via the metadata to individual user profiles. These detailed user profiles match community members to the content by linking their social and cultural identities to the content. Community members create a user profile the first time they log in. Each person enters their given name, nicknames, "skin name" (kin group / subsection), and gender before they choose a password. Following this, each individual connects to their larger kin networks by entering their mother's and father's family; and their parent's country. Finally, each individual is assigned one of three status levels: community member, traditional owner, and/or elder. Each status has associated levels of access to sacred materials, the ability to add content, and edit materials. For example, only elders can view and edit scared material, but anyone can add tags to their own collections. Similarly, because men and women may not view the same ritual materials a person logged in as a man would not be able to view women's materials. In a sense, each user views their own "mini-community archive" — a relational slice of the archive generated by the communities' own cultural terms and an individual's place in the community, their relationships, obligations and commitments (Christen, 2012). The Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari archive (the safe keeping place belonging to the Warumungu people) was our first attempt to encode cultural protocols and social networks into the logic of the platform.

2 Mukurtu Beta: the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal

As the Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari Archive was in use, Christen and technologists and librarians at the Washington State University Libraries formed a partnership with six tribes in the Plateau region. Building upon the university's Memorandum of Understanding (Native American Programs, 2017) with the tribal nations, the partnership sought to extend the alpha version of Mukurtu to incorporate existing library digital collections (with Dublin Core metadata), in a web based platform including multiple tribes across several states who share common histories, but also unique tribal values, languages, and collections. To test the concept of a multi-tribal version of Mukurtu, the WSU team worked with tribal partner representatives to develop a prototype of the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal (the Portal). The Portal allows members of the Plateau tribes to curate their cultural materials held in WSU's collections and at partner institutions at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA), the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) at the Smithsonian Institution, and the Northwest Museum of Art and Culture (MAC) in Spokane, Washington. The Portal expanded the functionality of the alpha Mukurtu platform creating an online, multi-tribal digital archive with more administrative features, extended access management parameters, and differential metadata requirements across fields and between Native communities and collecting institutions.

Figure 2: Plateau Peoples' Web Portal

The Portal extended the narrative features of the Mukurtu Wumpurrarni-kari archive to allow for multiple voices through the inclusion of community records, layered context, and diverse forms of metadata at the item and collection level. As we worked through the design and architecture of the database in the first two phases of development, we were not satisfied to simply have a Native "comments" section. Instead, we wanted an integrated metadata schema that placed Native knowledge side-by-side with institutional metadata. Rather than follow the "crowd sourcing" approach to social tagging that presumes all knowledge to be equal, the Portal highlights the unique knowledge sets of Native peoples of the Columbia Plateau alongside scholars who have contributed to these collections. In the display of every item in the Portal, Dublin Core metadata from the institution sharing the materials is included under the institutions' record and the tribal community, family or individual records are displayed alongside through multiple tabs. Tribal administrators have access to the uploaded content, but cannot alter the institutional record and metadata. Instead, tribal administrators manage the "Tribal Catalog Record" and/or the "Tribal Knowledge" tabs to add their own metadata, narratives, and audio or video comments. Similarly, institutional administrators (at WSU, the NAA, or the NMAI) can upload and enter metadata, but cannot alter the tribal catalog records or tribal knowledge fields. This system maintains the integrity of both institutional metadata and tribal community metadata while simultaneously showing the sharing of knowledge in multiple directions (Christen, 2011). The administrative system allows institutional metadata and added tribal metadata to be visible simultaneously. In this way, the Portal provides the framework for a new mode of collaborative curation, display, and classification that recognizes the significance of integrating multiple sets of standards and information systems.

Utilizing Mukurtu's features, the Portal highlights the rich history for each piece of content, linking histories of collection and colonization with those of survival and adaptation. For example, the WSU Libraries' Edwin Chalcraft Collection of glass lantern slides sparked a multi-tribal response. The collection, which none of the tribal members had seen before, consists of dozens of slides from the Chemawa Indian School (Salem, Oregon). The collection provided us with our first truly inter-tribal case study. As the tribal affiliates pointed out, Indian children from across the country attended the Chemawa boarding school not just the Northwest region. In the Portal, multiple tribal representatives contributed to the descriptions of the images. For example, one particular slide of the Chemawa School Bakery includes multiple linked narratives (Figure 3). Vivian Adams, Yakama Nation Librarian, contributed a commentary on the image in which she wrote that the "purpose of these schools was to teach Indian children how to become 'civilized' by taking them away from their familial ties and cultural influences. Some of the vocations like blacksmithing, the one my grandfather learned as a youth at one government school, quickly became obsolete during the industrial era." Added to the same image is a brief sound clip of Percy Brigham, a Umatilla Elder, who described eating mush for breakfast that contained worms, but if he didn't eat that 'mush,' he'd go hungry. These layered narratives are all part of a "digital heritage item" within the framework of Mukurtu. Replacing the notion of the stand-alone item or record with succinct metadata, the digital heritage item shows the overlapping, shared, sometimes competing and always growing conversations around culture, place, and history.

Figure 3: Community Records

3 Mukurtu Beta: the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal

As we developed the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal and created a beta version of Mukurtu with support from a National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Start Up grant, Christen presented the system's capabilities to many groups: indigenous communities, archivists, librarians, and museum curators. It became clear that there was a similar set of archival and content management needs that linked under-represented and marginalized communities. For example, the Squamish nation in Canada wanted an archive whose protocols could accommodate their intricate clan and family system; in New Zealand the Maori needed a system that could deal with extensive iwi (kin-based social networks), and in Kenya the Maasai sought a system that would allow them to differentiate materials meant for commercial purposes from those meant only for internal circulation; and LGBT archives wanted to protect the privacy of their donors while also providing access to sensitive materials to smaller groups. In every case, these communities requested flexible cultural protocols to manage the distribution, circulation, and reproduction of their cultural heritage. They also wanted customizable templates, adaptable user-access levels, and clear intellectual property management tools to make informed decisions about the circulation of their own materials.

With an IMLS National Leadership Advancing Digital Resources Grant in 2011, the WSU Mukurtu team, in a partnership with the Center for Digital Archaeology, Civic Actions, and Kanopi Studios updated the beta version of the platform to produce a stable and more easily upgradeable tool that would be available to more communities. In the process, Mukurtu changed from a custom project to a free and open source content management system tool. Emphasizing both an agile development model and community engagement, the philosophy behind Mukurtu's creation — to build a "safe keeping place" — drives all development, functionality and added features. Leveraging Drupal 7 as Mukurtu's base allowed the development team to focus on specific features, functions and areas of emphasis that set Mukurtu apart from other CMS options. Mukurtu is the only CMS that provides:

- Customizable, granular cultural protocol-driven access to digital content based on local knowledge systems;

- Pathways for sharing content and metadata between multiple community groups within the platform;

- Layered narratives and curation for materials that go beyond the "item" level to connect content, metadata, traditional knowledge and cultural narratives in one view;

- Flexible and clear licensing and labeling of content; and

- Selective metadata transfer between collecting institutions and Indigenous communities using Mukurtu's "roundtrip" feature.

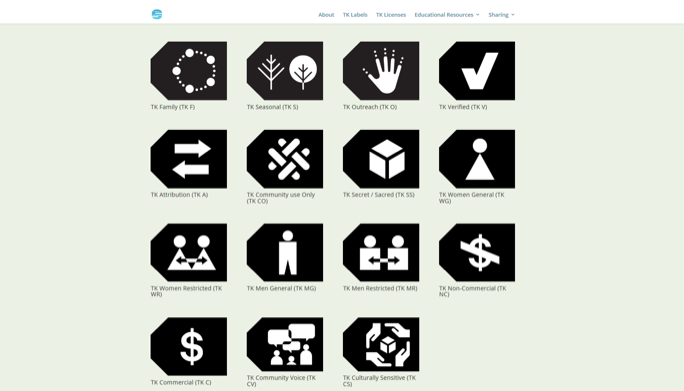

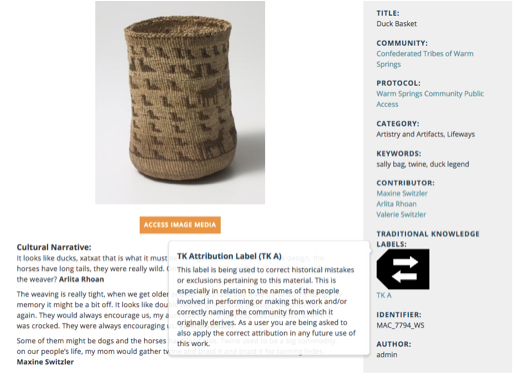

Mukurtu's selective sharing and vetting in features, along with the protocol level management and access functionality, balance the cultural needs of communities with the desire of non-Indigenous institutions desire to share content more publicly. In 2012, we launched Mukurtu CMS version 1.0 in Sydney, Australia and over the course of the next twelve months grew Mukurtu's community, held ten community workshops for training and continued user feedback and testing. In 2014 using a community focused software development model, Mukurtu CMS reached a 2.0 release and underwent a theming facelift, a complete code update, and the addition of new features including customization of the front page, community pages, and the addition of customizable Traditional Knowledge (TK) Labels. Built directly from community needs and input, the TK Labels are a prime example of a feature designed around specific cultural and historical needs. Because Indigenous communities do not legally own much of their patrimony, traditional or Creative Commons' licenses do not apply. Over two iterations of Mukurtu development, we created TK Labels to provide context to public domain and third-party owned works circulating to the general public. Items or collections within Mukurtu CMS can have a combination of customizable TK Labels including: seasonal (for materials that should only be accessible during certain seasons), sacred (for materials that are culturally sensitive) or attribution (so source communities can be named in addition to other creators of works) to signal to viewers the appropriate forms of circulation and access regardless of the copyright status.

Figure 4: Traditional Knowledge Labels

Figure 5: Traditional Knowledge Labels

4 Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes: A Community of Relations

The current Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes: A Sustainable National Platform for Community Archiving project grew out of simultaneous conversations from local communities using Mukurtu CMS and national repositories discussing ways to work with indigenous communities to facilitate content sharing. We also considered national conversations around digital tool building, sustainability, and the technological needs of diverse users, particularly the cultural values and social needs of underrepresented communities. An identified goal of the IMLS National Digital Program is to champion diversity and inclusion (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2015). A national digital platform as envisioned by the IMLS is a decentralized set of tools, services, support and training that aid local communities in doing on-the-ground work while connected to platforms, tools, and workflows. Mukurtu CMS embodies this idea by prioritizing the diversity of knowledge systems, cultural protocols, and social needs across communities while highlighting the biases coded into seemingly neutral standards and curatorial practices. The continued development of Mukurtu CMS through the Hubs and Spokes model will expand the Mukurtu CMS support structure, enhance the feature set, and grow the user base of Mukurtu CMS to ensure long term sustainability. The two main goals of the project are to train Mukurtu Hubs to provide support for their regions and continue Mukurtu CMS's community development. Working in tandem, the project builds sustainability at the community and platform level — indeed, the two are inseparable.

Over the three years of the project (2016-2019) Mukurtu Hubs will become regional support and training centers for the tribal archives, libraries, and museums — the spokes — in their areas. The Hubs and Spokes will work together with the WSU Mukurtu teams' community software development model used in previous phases of development to ensure that Mukurtu CMS remains a grassroots effort, with design, functions and features driven by local needs and reaches a 3.0 release by the end of the project. What we found through the process of open source development is that while the standard open source model provides an avenue for growing a development community, Mukurtu users do not have the resources, infrastructure, and programming skills to contribute to Mukurtu's development in the same way as other open source platforms. Recognizing that these differences are based on limited resources, and an underrepresented set of users, the proposed Hubs and Spokes model addresses this by maintaining the technical foundation of Mukurtu at WSU while collaborating with the Hubs to provide additional support and outreach, and the Spokes to provide community needs for updates and refinements to the platform. The Hubs will work directly with the Spokes using WSU's assessment workflow to document feature and functionality needs through user testing and on-going training modules. The Hubs — the University of Hawaii's Libraries and Department of Linguistics, the Alaska Native Language Archives at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, the University of Oregon Libraries, the University of Wisconsin's SLIS program and the Wisconsin Library Services, and Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and the Yale Indian Papers project — all have existing relationships with regional TALMs that provide a foundation for collaboration and commitments to a sustainable national platform that addresses the ethical curation of, and access to, cultural content.

In the first six months of the grant, we focused on start-up activities. These included training the trainers at the Mukurtu Hubs, articulating community engagement strategies, and building our shared team communication network. The Mukurtu Hubs have selected their Hub managers. The Hub manager is primarily responsible for maintaining communication with the Mukurtu Team at WSU and leading community engagement with the Spokes. In March of 2017, the first group meeting was held at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington. This meeting, affectionately dubbed Mukurtu CMS "boot camp," emphasized all aspects of using and supporting Mukurtu CMS. We discussed procedures for creating user stories for use in the agile development process, effective bug reporting, and community outreach techniques and successes. We focused on both the overall goal of sustainability — in terms of the software and the communities who use Mukurtu — as well as the practical aspects of implementing Mukurtu while collaborating with tribal partners. The boot camp training included the basics of setting up and using Mukurtu, community consultation practices and processes, and induction into Mukurtu's community software development model. The software development model process is built from a combination of existing "agile" models that emphasize iterative methods and user engagement and community building methodologies that rely on mutual respect and knowledge sharing. Together these methods form Mukurtu's community software development model that builds from on-the-ground, grassroots community needs around sharing, curating, and managing digital heritage materials to build, extend and expand features and functionality. The remainder of 2017 will be devoted to further virtual training, community engagement with Spokes, developing user stories based on direct community feedback, and initial development sprints.

5 Mukurtu CMS: A Shared Future

Over the short life of Mukurtu CMS, with a small staff and budget, we have developed a truly community-driven platform. We recognize the profound need for technologically and culturally responsive platforms for digital heritage stewardship. Over the last five years, during Mukurtu workshops and online trainings, through surveys supplemented by informal conversations with stakeholders, we have identified the need for new models for the shared curation cultural heritage. These models include the vetting of content for cultural sensitivities, support for Native languages, and the inclusion of historical context into diverse collections. The main needs we encountered during these collaborations are described as follows:

- Non-Indigenous collecting institutions want to share their collections with Indigenous communities and the public, and they know they have some content that is culturally sensitive (sacred objects, images of the deceased, maps which disclose archaeological sites, etc.), but they do not have a way to share the content online while respecting these cultural differences, nor do they know the best channels for contacting community representatives for vetting of the materials.

- Indigenous collecting institutions wish to make their own collections available to their communities online, but need a way to define access based on local, internal protocols.

- Indigenous institutions know that non-Indigenous collecting institutions hold materials pertaining to their tribe and they would like to add their own metadata to those collections online through their own CMS. Without a system that can facilitate easily moving not just content but also metadata between databases, tribes have limited access to these institutional collections for their own use, reuse and community access.

Mukurtu Hubs and Spokes will build capacity for individual Mukurtu CMS installations around the country, and by doing so will increase support and training opportunities for communities dong this significant cultural work. While this is happening there is a concomitant need to bring national repositories into this community-driven work of collaborative curation and ethical sharing of Indigenous cultural materials through a digital return process. The WSU Mukurtu team just completed a planning grant funded by the Andrew Mellon Foundation: "Mukurtu Shared: a Portal for Connecting Collections and Native Communities through a Collaborative Curation Model" to scope the technical, functional, training and community-related needs to build a platform for aggregating, curating, and sharing Native American library and archive collections online by connecting tribal and national repositories. The result is a roadmap for expanding the sharing capabilities within Mukurtu CMS to facilitate ethical and engaged content and metadata exchange between institutions and existing aggregators. Instead of content being pulled into aggregators without a cultural vetting process, the "Mukurtu Shared" workflow model proposed is designed to promote trust at all levels of content management and sharing by extending the notion of security past technical checks, to include cultural and ethical checks into the aggregation process. The roadmap includes: preservation micro-services, exposing a Mukurtu API for easier feature development, and enhanced support for complex metadata import and export (METS, MODS, EAD). In addition to the technical roadmap, the planning meetings showed the need for expanded training (imagined through a cohort of Mukurtu Fellows), an extended and documented collaborative curation workflow for institutions and shared resources for long-term partnerships between Native communities and collecting institutions.

The future of Mukurtu is embodied in these interrelated projects that move between local, national, regional and global contexts to imagine a different type of curation process. Like the dilly bag from which this project takes its name, we aim to open up spaces for sharing within a network of relationships that obligates us to act respectfully, to listen responsively, and to learn reciprocally.

References

| [1] |

Christen, K. (2011). Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation. American Archivist, 74(1), 185-210. |

| [2] |

Christen, K. (2012). Does Information Really Want to be Free?: Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness. The International Journal of Communication, 6, 2870-2893. |

| [3] |

Hunter, J., Koopman, B., & Sledge, J. (2004). Software Tools for Indigenous Knowledge Management. Museums and the Web 2003. |

| [4] |

Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2015). IMLS Focus 2015: The National Digital Platform Summary Report. |

| [5] |

Native American Programs. (2017). Washington State University Memorandum of Understanding. |

About the Authors

Kimberly Christen is an Associate Professor and the Director of the Digital Technology and Culture Program, the Director of Digital Projects, Native Programs, and the co-Director of the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University. She is the founder of Mukurtu CMS, the co-Director of the Sustainable Heritage Network and the Local Contexts initiative. More of her work can be found at her website.

Alex Merrill is the Head of Systems and Technical Operations for the Washington State University Libraries and the Director of Technology for the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University (CDSC). Alex studied History and Computer Science at Ball State University and received his MLIS from the University of Arizona in 2004. Alex began working with Mukurtu CMS (and the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal) in 2008.

Michael Wynne is the Digital Applications Librarian in the Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation at Washington State University. Michael received a BSc in Linguistics from the University of Victoria and an MLIS from the iSchool at the University of British Columbia in 2015. Michael is the primary support specialist for Mukurtu CMS, and has been working with Mukurtu, the Plateau Peoples' Web Portal, and other projects at WSU since 2015.